1. Introduction

1.1. Autism Spectrum Disorder

Patients with Autism Spectrum disorder (ASD) exhibit a range of characteristic behaviours and atypical communication styles that can lead to difficulties establishing relationships with others, and an associated significant degree of psychological agitation [

1]. Symptom severity is heterogenous. Some patients are completely non-verbal, some require assistance with basic activities of daily living, and others function independently with only mild difficulties [

2]. Roughly two thirds of patients with ASD have a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, with the most frequent comorbidities being ADHD, anxiety and depressive disorders or intellectual disability [

3,

4,

5]. These comorbidities complicate the management of these patients, and may further increase their agitation and distress.

The prevalence of ASD varies among different countries, likely due to differences in diagnostic protocols and societal attitudes toward the condition. However it is generally acknowledged that there has been an increasing rate of ASD diagnosis over the past several years particularly in developed countries [

6]. There have also been several notable portrayals of individuals with ASD in popular Western media over the past two decades [

7]. This has been accompanied by a massively increased demand for services for patients with ASD, and resultant increased economic costs associated with government subsidised therapies, tailored education services, and dedicated caregivers [

8]. Australia has one of the highest rates of ASD diagnoses among developed countries, estimated at 1.7% in 2016 [

9]. Individuals with ASD therefore represent an established patient group, with significant needs that are unique and should be well understood by health professionals.

1.2. Aggressive Behaviour

Although it is not a cardinal symptom in the diagnostic criteria for ASD, increased aggression and aggressive behaviours are common manifestations that complicate management. Several retrospective cohort studies suggest that children and adolescents with ASD exhibit aggressive behaviours toward others at a higher rate than the general population, with most measuring rates above 50% [

10]. They also tend to score higher values on subjective measurements scales [

10]. Day-to-day aggressive behaviours are less prevalent among adults with ASD, however still increased compared to the general population [

11]. Adults with ASD also score higher for aggressive factors on subjective rating scales [

12]. Risk factors for aggression among individuals with ASD include younger age as outlined above, intellectual disability, impaired language and sensory processing [

13,

14].

This increased propensity for aggression carries a greater need for appropriate behavioural management. Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) who exhibit a heightened prevalence of atypical behaviours—such as whimsical, aggressive, and self-aggressive demeanours—are inclined to manifest lower nonverbal IQ, diminished communicative abilities, augmented impairment in social interactions, and an increased exhibition of stereotyped behaviours. Furthermore, amidst stressful situations, low-functioning ASD customarily mitigate stress through aggressive behaviours, contrasting with their typically developing counterparts who navigate and articulate their stress via cognitive skills, social interaction, and both verbal and nonverbal communication. Such cognitive skills encompass coping mental strategies, symbolization capacities, representation, and the anticipation of stressful scenarios.

Communication, being the conduit through which information is reciprocally exchanged amongst individuals in various forms, transcends the boundaries of language, enveloping nonverbal communication and the comprehension of symbols. Person with ASD seemingly exhibit a diminished awareness towards language, and they tend to employ gestures infrequently and in less meaningful communicative forms. Children with ASD, who cultivate functional communication, often manifest atypical communication styles, which may include echolalia, contact gestures, pronoun reversals, and neologisms, likely developing due to their constrained understanding of the meanings and intentions embedded within symbolic language forms.

Moreover, the impairments intrinsic to ASD are frequently delineated as qualitative in nature. When juxtaposed—for age and developmental language level—with peers diagnosed with mental retardation, children with ASD demonstrated substantial comparability in objective communication measures, such as nodding or shaking heads whilst speaking, visual engagement with the interviewer, and the total incidence of smiles. However, they scored markedly lower on subjective communication measures, such as engagement and conversational fluidity.

Children with ASD may utilize language primarily to fulfil needs and address queries, yet they tend to comment with lesser frequency, employing language as a pragmatic tool—for instance, for item requisition. Intriguingly, they might not proactively seek engagement and tend to articulate their needs or desires devoid of any anticipatory response or engagement from others [

15].

1.3. Psychiatric comorbidities in ASD

General clinical practice does indicate that ASD and psychoses might co-exist more frequently than what might be anticipated by chance. However recognising psychosis in presence of ASD can be complex task. Psychosis can escalate the level of aggression due to perceived danger around the individual. There is also substantial proof of several common features between the two conditions, when viewed from a neurobiological angle. The rates of heritability for both are estimated to be quite high, lying in the range of 50–80%. Recent genetic researches have showcased that common copy number variants (CNVs; alterations in the DNA sequence throughout the genome) can contribute towards the risk for both schizophrenia and ASD [

16].Typically people with ASD can present with passivity delusions, delusions of reference, and unsual ideas. Impaired language and communication skill can make it difficult to differentiate between psychosis and core symptoms of ASD[

17].Mood disorders like depression and bipolar type , are present in ASD higher than general population. Often diagnostic work up becomes challenging due to poor recognition of symptoms by family and health care worker leading to misdiagnosing and underdiagnosis. People with ASD often self-medicate with substances to treat emotional distress, loneliness, social isolation and severe anxiety. The use of substance can increase the suicidal and aggressive behaviour. Its not so uncommon that ASD can present with features of catatonia such as posturing, grimacing, negativism, waxy flexibility, echolalia, echopraxia, stereotypy, verbigeration and severe unpredictable psychomotor agitation. [

18].

People with autism are vulnerable to polyvictimization. It is characterized as experiencing numerous types of abuse, maltreatment, or violence, which is not limited to traditional crime, child abuse, victimization by peers and siblings, sexual assault, as well as witnessing and indirect victimization. Presence of ADHD in ASD can even further escalate supervision neglect, physical neglect, and physical and contact sexual abuse [

19].

The lack of reciprocity, social naivety, compulsivity and resistance to change in ASD often escalate the high of criminal behaviour. Childhood psychosocial adversities and maladjustment often llead to future offending behaviour in ASD [

20].

1.4. Therapies

There have been considerable efforts to establish methods of managing aggression in patients with ASD, with a focus on both psychological therapies and medications. The majority of studies have exclusively examined children with ASD, however there have been several recent reviews on adult patients [

21,

22,

23]. Applied behaviour analysis is the most well-established psychological model for behavioural management in patients with ASD. It incorporates close contacts of patients and patients themselves, and focuses on the exploration of behaviours through written and spoken methods, the use of positive reinforcement for productive behaviours, and the examination of various methods of communication [

24]. Other non-pharmacological methods of treating aggression include exercise and music therapy, however research on these therapies in adults are limited by small sample sizes [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

There have been several trials that have examined the regular use of various drugs in the management of aggression for adult patients with ASD. Risperidone is the most studied drug, with several randomised control trials showing reductions in aggressive behaviours [

22]. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine has also been shown to reduce aggressive behaviours [

30]. There is also some evidence from varied cohort studies and case series that support the use of other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and atypical antipsychotics in these patients, however these studies are lacking in scope and numbers. One significant factor that limits studies on pharmacotherapies in patients with ASD is the high rate of psychiatric comorbidities. Since most patients with ASD have comorbid psychiatric conditions including mood and psychotic disorders, they are likely to already be treated with psychotropic medications. This makes it difficult to establish reliable control groups. The significant heterogeneity in comorbid conditions makes it difficult to compare these patients retrospectively as well. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on the use of sedatives for acute psychiatric presentations.

1.5. Emergency Presentations

While patients with ASD remain a relatively rare patient population, their burden on the emergency department should not be underestimated. Children and adolescents with ASD present to the emergency department of hospitals more frequently than those without this diagnosis [

31,

32]. Adults with ASD also present more frequently for both medical and psychiatric conditions [

33]. Patients with ASD are more likely to be admitted, and experience longer hospital stays [

34,

35]. They are more likely to attempt suicide [

34,

36]. One study found that the healthcare costs to patients with ASD who present to ED were more than double on average compared to other patients without ASD [

37]. As patients with ASD are becoming more frequent presenters to the emergency department, it is important to understand the unique risks and challenges involved with their acute behavioural management.

1.6. Sedatives

Aggressive and agitated patients are not uncommon in the hospital emergency department. One study in Australia found that security calls for unarmed threats occurred in 3.2 in every 1000 emergency department patients, with the most frequent associated factor being a pre-existing significant psychiatric disorder in over half of patients [

38]. Another study in 2006 recorded a rate of 5.5 per 1000 emergency presentations [

39]. These patients should be managed in the first instance by non-pharmacological techniques including verbal de-escalation, the involvement of family and friends and ideally, the movement to favourable environments with more space, fewer neighbouring patients and fewer risky surrounding items. However, in the majority of recorded behavioural agitation events, these methods fail and physical or chemical sedatives are required [

40]. Chemical sedation is preferred and more frequently used compared to physical restraints due to the significant psychological impact of physical restraints [

41]. Oral administration is preferred to intramuscular or intravenous sedatives due to easier titration, lower risks of side-effects, and reduced associated psychological distress. The two most common types of sedative drugs used in emergency departments for agitation today are benzodiazepines and antipsychotics, with some evidence for a synergistic effect when using both [

42]. However, there are significant side-effects associated with modern sedatives, including prolonged fatigue, an increased risk of falls and injuries and addiction [

43]. Notably, a meta-analytic review found that up to a third of patients who received chemical sedatives in hospital emergency departments experienced severe adverse events including respiratory depression, QT prolongation and death [

42]. Additionally, patients associate a great deal of negative emotion with receiving excessive sedation against their will [

44]. Benzodiazepines can be associated with a degree of behavioural disinhibition that can last longer than their acute sedative effect. Prolonged courses can lead to tolerance and dependence [

45].

1.7. Study Aims

Patients with ASD represent a unique and vulnerable patient group that present more frequently to emergency department and are more likely to express aggressive behaviour. This may lead to these patients requiring chemical sedation at higher doses and rates being at increased risk of adverse events. However, there are no previous studies that have examined the administration of sedatives to patients with ASD in acute settings. To fill this gap in knowledge, the present study aims to determine whether adult patients with ASD who present with acute psychiatric illnesses receive more sedatives in the emergency department.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Measurement

A retrospective case-matched cohort study was performed on patients presenting to the emergency department from the start of January 2021 to the end of December 2021. At the hospital involved with this study, patients presenting with acute psychiatric conditions and require specialist support are referred to the Emergency Mental Health team, comprising experienced mental health clinicians and when required, consultant psychiatrists. The list of patients referred in this way throughout the year of 2021 was manually searched for relevant cases. Case participants had to be aged over 18, with a prior formal diagnosis of ASD. Those with documentation of an unclear diagnosis, such as those with ‘suspected ASD’ were excluded. There were five patients who presented more than three times over the year, who were excluded. This was because these patients were treated differently to other patients as ‘known’ or ‘frequent’ presenters, and often discharged rapidly from the department. After cases and controls were identified from this list, further information was obtained via the online electronic medical record.

Due to the small number of cases, a case-matched cohort method was used where the same list of patients was searched for suitable controls and matched at a one-to-one ratio. Controls had to have the same sex, an age within five years and a similar ED length of stay. Length of stay was used as a matching parameter as there was significant heterogeneity in the amount of time that patients spent in the emergency department, and this was expected to contribute significantly to the likelihood of receiving sedatives. Patients who stayed in the emergency department for under 20 hours were matched with control participants with a length of stay within 5 hours. Those who stayed for more than 20 hours were matched with control participants with a length of stay within 10 hours. Controls were manually searched and selected in order of closest proximity to the presenting date of cases. Other demographic characteristics were recorded for all patients.

2.2. Statistical Methods

As the types of sedatives varied between patients, doses were converted to standardised equivalents to allow comparison. Benzodiazepines were converted to diazepam equivalents [

46]. Antipsychotics were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents as per the defined daily doses method [

47].

Data were compiled and stored using Microsoft Excel and analysed using R 4.3.1 [

48,

49]. Two-tailed repeated measures T-tests were performed on doses of sedatives received by cases and controls, with an alpha level of 0.05. Pearson chi-square tests were performed on measured demographic characteristics and frequencies of sedative administration.

3. Results

3.1. Matched Demographic Characteristics

There were 41.9% female participants among cases and controls. The mean age of patients with ASD was 26.7 (SD = 7.9), which was similar to the mean age of controls of 27.4 (SD = 7.6). The mean hospital length of stay was 13.4 hours (SD 8.6) among cases and 14.0 (SD 7.0) among controls. These data are reported in

Table 1.

3.2. Non-Matched Demographic Characteristics

A statistically significant difference was observed between 32.6% of patients with ASD who also had an intellectual disability, compared to only 4.7% of patients without ASD (χ

2=12.19, df=1, p<0.01). Patients with ASD also had a higher rate of ADHD of 25.6% compared to 11.6%, however this was not statistically significant. Rates of other comorbid pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses, presenting complaints, being brought in by police and multiple presentations were similar between cases and controls with no statistically significant differences. The most common presenting complaint was suicidal ideation or attempts at 60.5% among patients with ASD, and 69.8% among controls, followed by abnormal behaviour at 32.6% and 20.9%, then hallucinations and delusions at 7.0% and 9.3% respectively. 20.9% of patients with ASD were brought in by police, compared to 27.9% among controls. 48% of patients with ASD had more than one presentation over the year, compared to 39.5% of controls. These data are reported in

Table 2.

3.3. Sedative Doses

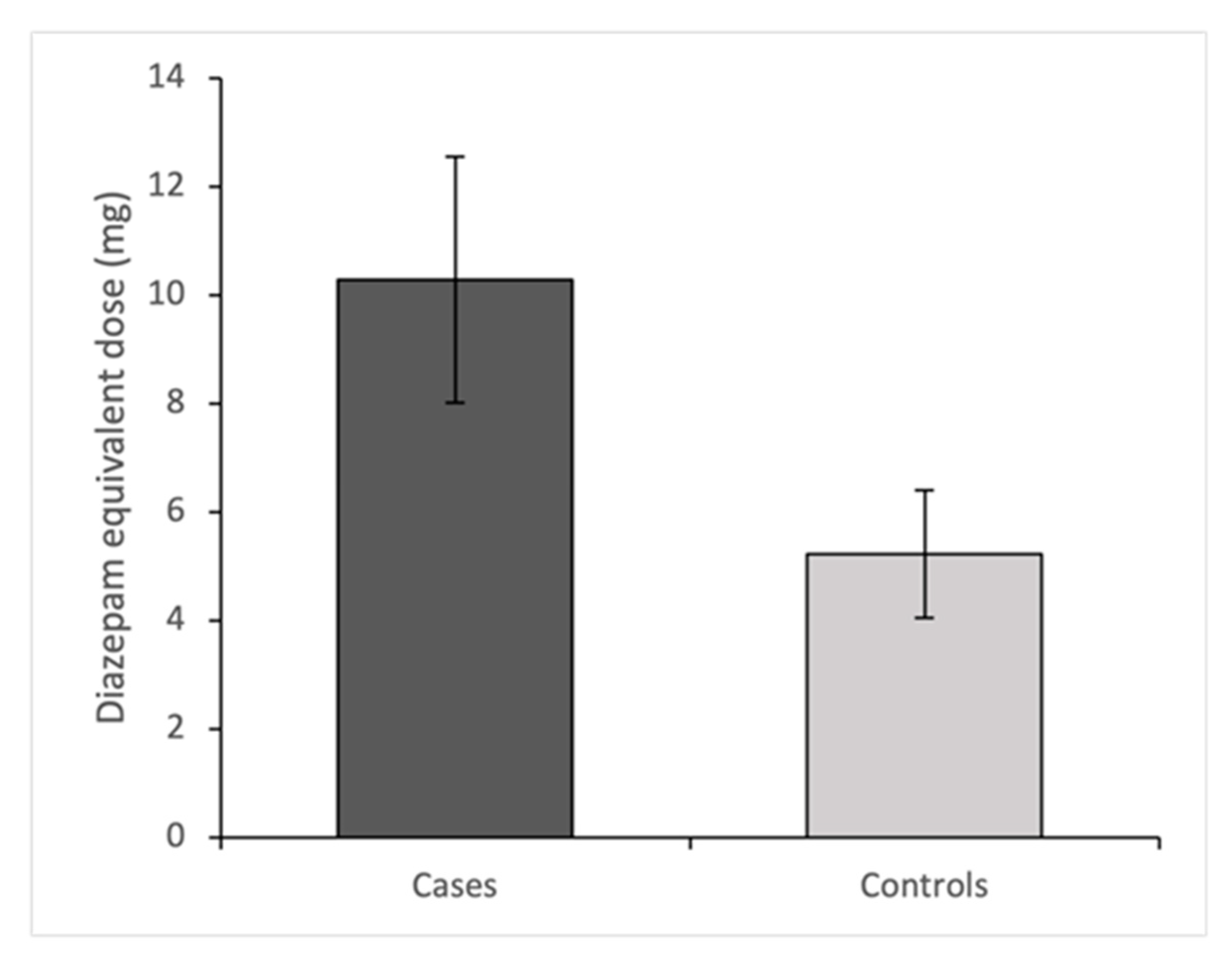

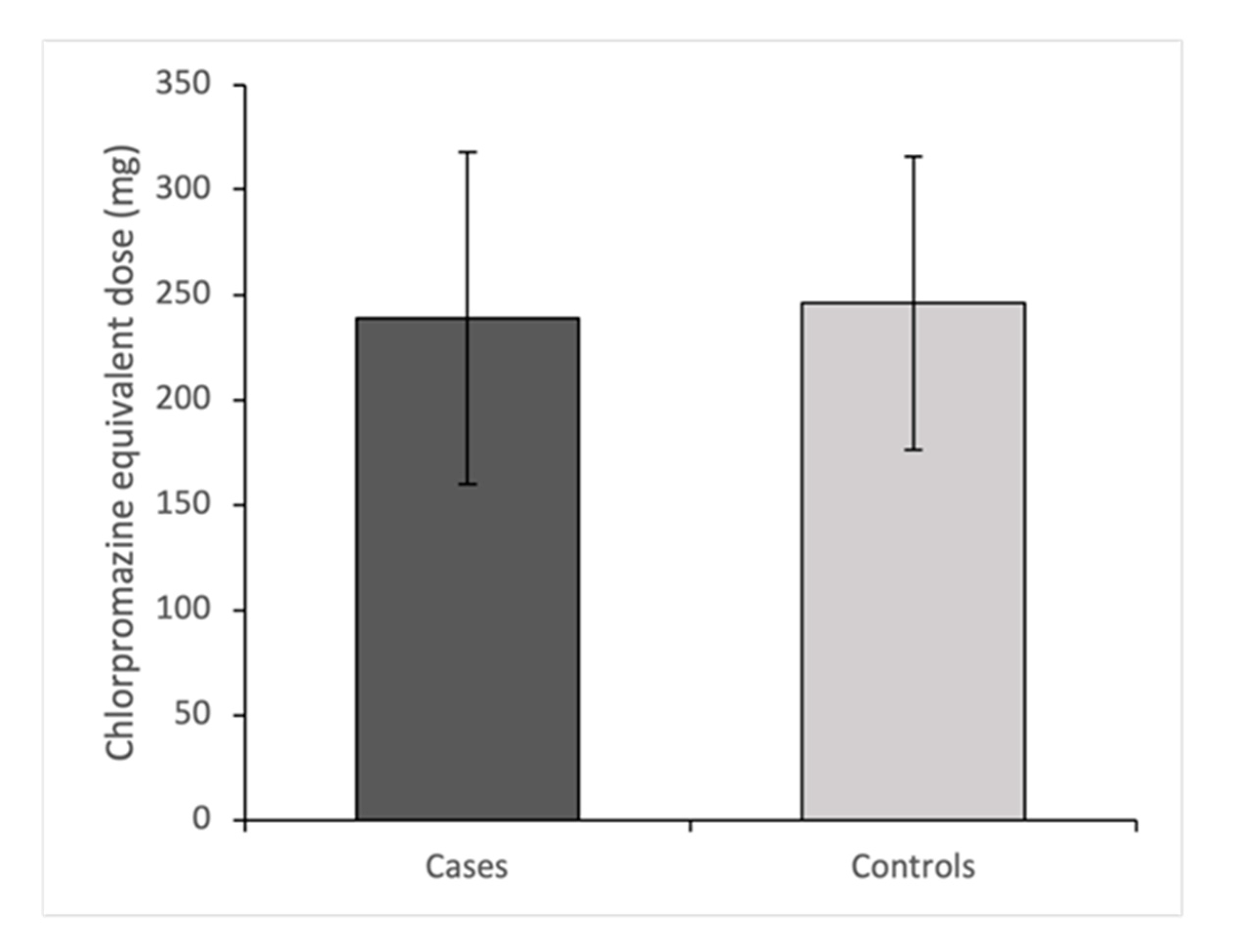

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show mean diazepam and chlorpromazine equivalent doses for cases and controls with associated 95% confidence intervals. Patients with ASD received 5.1mg more dose-equivalent diazepam in comparison to matched controls (95%CI: 0.41-9.71). This difference was statistically significant (T=2.20, df=42, p=0.034). Patients with ASD received 7.0mg less dose-equivalent chlorpromazine in comparison to matched controls (95%CI: -191.41-177.46). This difference was not statistically significant (T=0.08,, df=42, p=0.94).

3.4. Sedative Classes

A higher proportion of patients with ASD received benzodiazepines at 60.5% compared to 46.5% among controls, with a difference that was not statistically significant. A lower proportion of 30.2% of patients with ASD received antipsychotics compared to 44.1% among controls, with a difference that was not statistically significant. There were identical numbers of patients who received both types of sedatives, and patients who received no sedatives between groups. No patients encountered immediate severe adverse events including respiratory compromise, paradoxical agitation or cardiac events. These data are shown in

Table 3.

3.5. Sedative Types

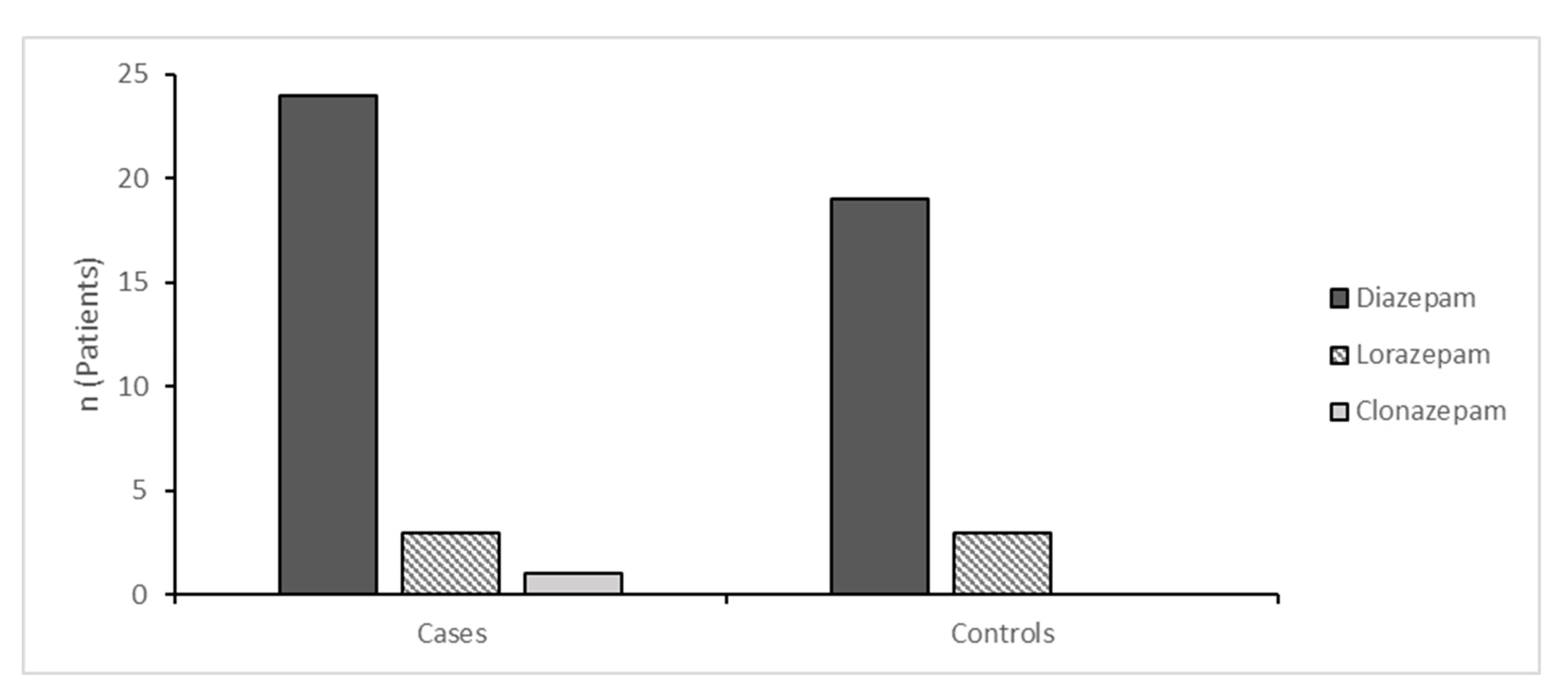

Figure 3 shows the types of benzodiazepines used among cases and controls, excluding intramuscular midazolam which is reported in

Table 4. Diazepam was the most commonly used benzodiazepine, used in 24 cases and 19 controls. Other benzodiazepines included lorazepam and clonazepam which were used in a very small number of both cases and controls.

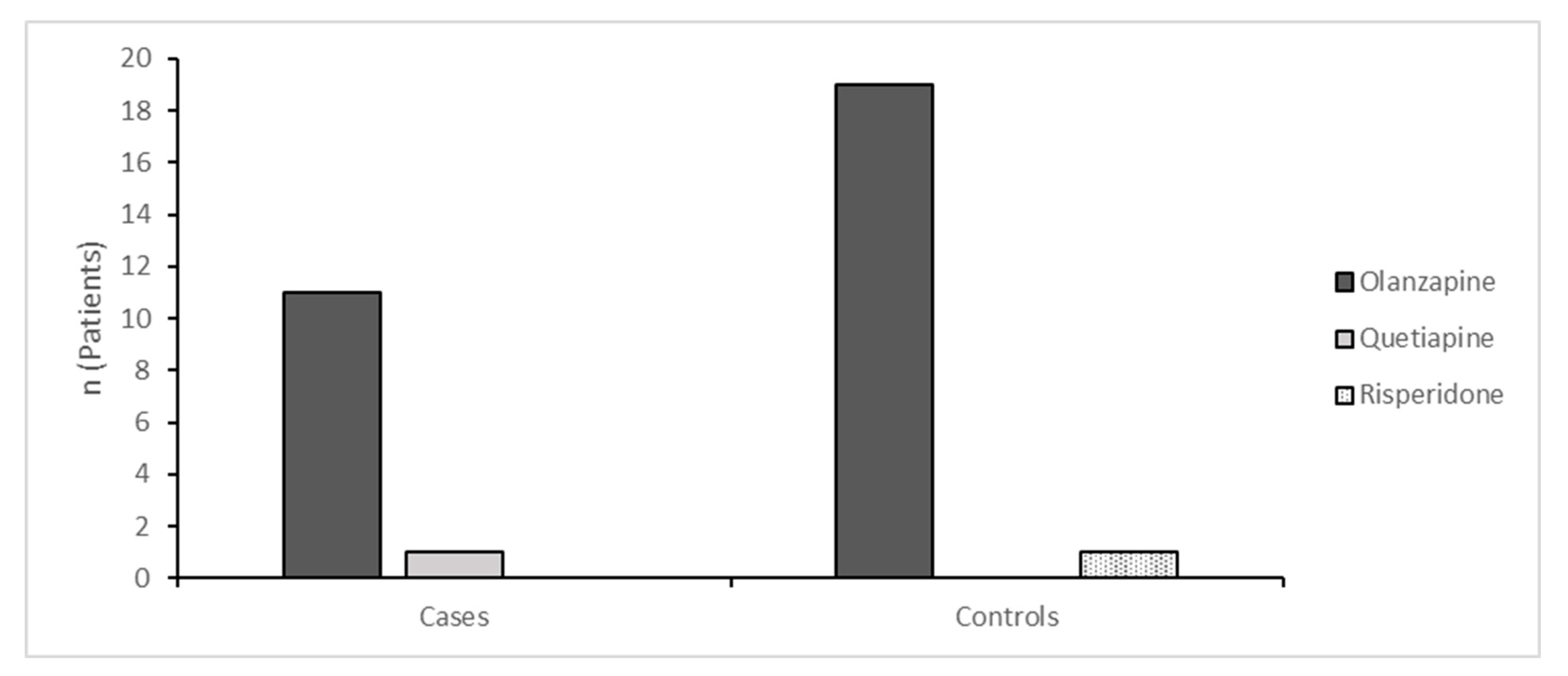

Figure 4 shows the types of antipsychotics administered to cases and controls, excluding intramuscular droperidol which is reported in

Table 4. Olanzapine was the most frequently used antipsychotic, used in 11 cases and 19 controls. The only other oral antipsychotics were quetiapine administered to one case, and risperidone administered to one control.

3.6. Intramuscular Sedatives

Four patients with ASD received intramuscular sedatives compared to one control patient, which was not statistically significantly different. Droperidol was the most frequently used intramuscular agent, in four cases and one control. Only one patient received midazolam, and only one control patient received intramuscular sedation. One patient with ASD received both droperidol and midazolam. There was no statistical difference between frequency of administration of midazolam or droperidol between cases and controls. These data are reported in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

4.1. Sedatives

This study shows evidence that patients with ASD receive increased overall doses of benzodiazepines in the emergency department compared to patients who present similarly but do not have a prior diagnosis of ASD. While the observed increased dose of benzodiazepines was modest, it does represent a potentially increased degree of harm to patients with ASD from prolonged sedative effects and psychological distress. Increased sedation may be necessary for patients with ASD, as these patients are more likely to express aggressive behaviours toward others and injurious behaviours toward themselves [

50]. On the other hand, it may also be possible that physicians have a lower threshold to use sedatives because they fail to recognise the unique difficulties with communication and behaviour exhibited by these patients. A primary presenting complaint of a psychiatric nature increases the risk of receiving sedation or restraints in the emergency department [

40]. However, it is unclear whether treating physicians have a lower threshold to sedate such patients, or whether such patients truly require sedation over less invasive means of behavioural management.

The choice of sedative medications for agitation in emergency settings varies widely among different institutions and across different countries [

51]. In Australia, the first-line oral medications are diazepam and olanzapine, which is consistent with our findings [

52]. There is evidence that antipsychotics and combination treatments have a stronger sedative effect, and are associated with a lower likelihood of receiving repeat sedation and a lower risk of adverse events compared to benzodiazepines [

42]. However, in our study benzodiazepines were used more frequently for patients with ASD compared to controls. The reasons for this are not clear. Clinicians may want to avoid stronger first-line sedatives among patients with ASD. It is also possible that clinicians view agitation as a component of ASD rather than another psychiatric condition. While antidopaminergic effects are desirable among patients who have agitation associated with other psychiatric conditions such as psychosis, mania or anxiety, clinicians may want to avoid these effects among patients who are agitated in part due to their ASD. Notably, studies on regular medications for adult patients with ASD show an aggression lowering effect for atypical antipsychotics including risperidone and quetiapine [

50,

53]. It is difficult, however, to extrapolate these findings to olanzapine as it is a different antipsychotic used in acute settings. Nevertheless, there appears to be a difference in how patients with ASD are acutely sedated both in terms of dosage and class of sedative. Further research may help establish whether there is an advantage to these approaches.

4.2. Intramuscular Sedatives

There were four patients with ASD who received intramuscular sedation compared to only one control patient. Although this difference in rates was too small to be statistically significant, we theorise that patients with ASD may be more likely to receive intramuscular sedation for the same reasons that they receive greater rates of oral sedation. As intramuscular sedatives carry a greater risk of more serious side-effects, this represents another potential source of increased harm. This may represent an avenue for further research, but adequate sample sizes may be difficult to achieve given the overall rarity of patients with ASD in hospitals coupled with the low overall rate of intramuscular sedation. Droperidol was the intramuscular agent of choice for most patients in this study, however we note no notable advantage of either droperidol or midazolam in previous trials [

54,

55].

4.3. Non-Pharmacological Interventions

Children with ASD are more likely to exhibit disruptive behaviours including physical and verbal aggression toward others and self-injury [

56]. There are a significant number of interventions aimed at young children with ASD, which have been studied extensively [

57,

58]. However, there is a lack of published literature focusing on adults with ASD. Prior research for adults has focused on long-term medications and functional assessments rather than behavioural interventions or acute de-escalation techniques [

59]. Longitudinal studies suggest that challenging behaviours vary widely in adult patients with ASD, and suggest that these behaviours may decrease as patients get older [

60]. They are also more likely to have received behavioural therapies and psychological interventions, which may attenuate their symptoms. Such patients may exhibit the characteristic speech patterns and communication difficulties associated with ASD, but may also be more competent at controlling their aggressive and disruptive behaviour [

61]. Further research into acute interventions for adult patients with ASD who are experiencing acute psychological distress may assist in reducing the need for sedation and potential associated risks.

4.4. Limitations

The primary limitation of this study was small sample size and associated statistical power. Although patients with ASD with acute psychiatric conditions are overrepresented in the emergency department compared to the general population, they are still very small in overall number [

32]. Case-matched design was utilised to compensate for the low number of cases, however it was still difficult to establish a statistical difference, and the frequency of intramuscular sedation was too low to effectively compare. Future studies would benefit from larger cohorts and established statistical power estimates.

Another potential limitation of this study was matching on ED length of stay. Due to the low overall number of cases compared to controls and significant heterogeneity in ED length of stays, we chose to match based on this characteristic rather than rely on measurement and adjustment in retrospective statistical analysis. However previous studies have shown that patients with ASD are more likely to spend longer in the emergency department, suggesting that this is an important independent factor by itself [

35]. An alternative method for controlling for ED length of stay would be measuring it and adjusting for it in a multivariate analysis rather than using it to match patients.

5. Conclusion

Attempts should always be made to reduce the use of sedative medications in favour of other techniques for behavioural management. These include verbal de-escalation, reducing sensory stimuli, one-to-one nursing, prompt security presence and the involvement of family or friends. Since patients with ASD are at a higher risk of receiving sedatives, efforts should be made to recognise their patterns of behaviour and difficulty, to understand them and formulate constructive and safe ways to manage their behaviour.

Funding

There was no funding received to support the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Arasu and Dr Naveen Thomas report no conflicts of interest. Dr Das reports a current grant from Otsuka & NWMH Seed fund.

References

- American Psychiatric Association DS, American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American psychiatric association; 2013 May.

- Sharma SR, Gonda X, Tarazi FI. Autism spectrum disorder: classification, diagnosis and therapy. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2018 Oct 1;190:91-104.

- Simonoff, E.; Pickles, A.; Charman, T.; Chandler, S.; Loucas, T.; Baird, G. Psychiatric Disorders in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Associated Factors in a Population-Derived Sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, M.W.; Greaves-Lord, K.; Grove, J.; Nørgaard-Pedersen, B.; Hougaard, D.M.; Mortensen, E.L. Psychiatric comorbidities in autism spectrum disorders: findings from a Danish Historic Birth Cohort. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 20, 599–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, R.; Ong, R.C.; Bolognani, F. Psychiatric comorbidities and use of psychotropic medications in people with autism spectrum disorder in the United States. Autism Res. 2017, 10, 2037–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Shohaimi, S.; Jafarpour, S.; Abdoli, N.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Mohammadi, M. The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maich, K. Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Media: Storied Reflections of Societal Views. Brock Educ. J. 2014, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, N.; Janssen, J. The Economic Costs of Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Literature Review. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 2873–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, M.; Sciberras, E.; Brignell, A.; Ihsen, E.; Efron, D.; Dissanayake, C.; Williams, K. Autism spectrum disorder: Presentation and prevalence in a nationally representative Australian sample. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2015, 50, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.P.; Zuckerman, K.E.; Hagen, A.D.; Kriz, D.J.; Duvall, S.W.; van Santen, J.; Nigg, J.; Fair, D.; Fombonne, E. Aggressive behavior problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and correlates in a large clinical sample. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.L.; Rivet, T.T. Characteristics of challenging behaviours in adults with autistic disorder, PDD-NOS, and intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2008, 33, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogert, F.v.D.; Sizoo, B.; Spaan, P.; Tolstra, S.; Bouman, Y.H.A.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Roza, S.J. Sensory Processing and Aggressive Behavior in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominick, K.C.; Davis, N.O.; Lainhart, J.; Tager-Flusberg, H.; Folstein, S. Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2007, 28, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, I.L.; Tsiouris, J.A.; Flory, M.J.; Kim, S.-Y.; Freedland, R.; Heaney, G.; Pettinger, J.; Brown, W.T. A Large Scale Study of the Psychometric Characteristics of the IBR Modified Overt Aggression Scale: Findings and Evidence for Increased Self-Destructive Behaviors in Adult Females with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2009, 40, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giacomo, A.; Craig, F.; Terenzio, V.; Coppola, A.; Campa, M.G.; Passeri, G. Aggressive Behaviors and Verbal Communication Skills in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Glob. Pediatr. Heal. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giorgi, R.; De Crescenzo, F.; D’alò, G.L.; Pesci, N.R.; Di Franco, V.; Sandini, C.; Armando, M. Prevalence of Non-Affective Psychoses in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribolsi, M.; Nastro, F.F.; Pelle, M.; Medici, C.; Sacchetto, S.; Lisi, G.; Riccioni, A.; Siracusano, M.; Mazzone, L.; Di Lorenzo, G. Recognizing Psychosis in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 768586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, A.; Butler, M.G. The Autism Spectrum: Behavioral, Psychiatric and Genetic Associations. Genes 2023, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellström, L. A Systematic Review of Polyvictimization among Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity or Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofvander, B.; Bering, S.; Tärnhäll, A.; Wallinius, M.; Billstedt, E. Few Differences in the Externalizing and Criminal History of Young Violent Offenders With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume K, Steinbrenner JR, Odom SL, Morin KL, Nowell SW, Tomaszewski B, Szendrey S, McIntyre NS, Yücesoy-Özkan S, Savage MN. Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism: Third generation review. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2021 Nov 1:1-20.

- Im, D.S.; S. , D. Treatment of Aggression in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 35–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S. E.; Srivorakiat, L.; Wink, L. K.; Pedapati, E. V.; Erickson, C. A. Aggression in autism spectrum disorder: presentation and treatment options. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, ume 12, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis.

- Allison, D.B.; Basile, V.C.; MacDonald, R.B. Brief report: Comparative effects of antecedent exercise and lorazepam on the aggressive behavior of an autistic man. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1991, 21, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott Jr RO, Dobbin AR, Rose GD, Soper HV. Vigorous, aerobic exercise versus general motor training activities: Effects on maladaptive and stereotypic behaviors of adults with both autism and mental retardation. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 1994 Oct;24(5):565-76.

- Boso, M.; Emanuele, E.; Minazzi, V.; Abbamonte, M.; Politi, P. Effect of Long-Term Interactive Music Therapy on Behavior Profile and Musical Skills in Young Adults with Severe Autism. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2007, 13, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundqvist, L.-O.; Andersson, G.; Viding, J. Effects of vibroacoustic music on challenging behaviors in individuals with autism and developmental disabilities. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, M.; Meulenbroek, R. Effects of physical exercise on Autism Spectrum Disorders: A meta-analysis. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowsky, D.S.; Shetty, M.; Barnhill, J.; Elamir, B.; Davis, J.M. Serotonergic antidepressant effects on aggressive, self-injurious and destructive/disruptive behaviours in intellectually disabled adults: a retrospective, open-label, naturalistic trial. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999, 8, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deavenport-Saman, A.; Lu, Y.; Smith, K.; Yin, L. Do Children with Autism Overutilize the Emergency Department? Examining Visit Urgency and Subsequent Hospital Admissions. Matern. Child Heal. J. 2015, 20, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu G, Pearl AM, Kong L, Leslie DL, Murray MJ. A profile on emergency department utilization in adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2017 Feb;47(2):347-58.

- Nicolaidis, C.; Raymaker, D.; McDonald, K.; Dern, S.; Boisclair, W.C.; Ashkenazy, E.; Baggs, A. Comparison of Healthcare Experiences in Autistic and Non-Autistic Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey Facilitated by an Academic-Community Partnership. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 28, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Mikami, K.; Akama, F.; Yamada, K.; Maehara, M.; Kimoto, K.; Kimoto, K.; Sato, R.; Takahashi, Y.; Fukushima, R.; et al. Clinical features of suicide attempts in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013, 35, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, D.; Hall, M.; Oreskovic, N.M.; Aryee, E.; Broder-Fingert, S.; Perrin, J.M.; Kuhlthau, K.A. Emergency Department Utilization of Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 52, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen MH, Pan TL, Lan WH, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Su TP, Li CT, Lin WC, Wei HT, Chen TJ, Bai YM. Risk of suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder: A nationwide longitudinal follow-up study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2017 Aug 29;78(9):1709.

- Vohra, R.; Madhavan, S.; Sambamoorthi, U. Emergency Department Use Among Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1441–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, J.C.; Bennett, D.; Rawet, J.; Taylor, D.M. Epidemiology of unarmed threats in the emergency department. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2005, 17, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Downes, M.; Healy, P.; Page, C.B.; Bryant, J.L.; Isbister, G.K. Structured team approach to the agitated patient in the emergency department. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2009, 21, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.H.; Crispino, L.; Parker, J.B.; McVaney, C.; Rosenberg, A.; Ray, J.M.; Whitfill, T.; Iennaco, J.D.; Bernstein, S.L. Characteristics and Severity of Agitation Associated With Use of Sedatives and Restraints in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 57, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.H.; Taylor, R.A.; Ray, J.M.; Bernstein, S.L. Physical Restraint Use in Adult Patients Presenting to a General Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2019, 73, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korczak, V.; Kirby, A.; Gunja, N. Chemical agents for the sedation of agitated patients in the ED: a systematic review. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 34, 2426–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Yudofsky, S.C.; Silver, J.M. Pharmacological and Behavioral Treatments for Aggressive Psychiatric Inpatients. Psychiatr. Serv. 1993, 44, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg WM, Moore-Duncan L, Herron R. Patients’ attitudes toward having been forcibly medicated. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online. 1996 Dec 1;24(4):513-24.

- Griffin CE, Kaye AM, Bueno FR, Kaye AD. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system–mediated effects. Ochsner Journal. 2013 Jun 20;13(2):214-23.

- Borrelli, E.P.; Bratberg, J.; Hallowell, B.D.; Greaney, M.L.; Kogut, S.J. Application of a diazepam milligram equivalency algorithm to assess benzodiazepine dose intensity in Rhode Island in 2018. J. Manag. Care Spéc. Pharm. 2022, 28, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leucht, S.; Samara, M.; Heres, S.; Davis, J.M. Dose Equivalents for Antipsychotic Drugs: The DDD Method: Table 1. Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 42, S90–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://office.microsoft.com/excel.

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Im, D.S.; S. , D. Treatment of Aggression in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 35–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Leonard, J.B.; Corwell, B.N.; Connors, N.J. Safety and efficacy of pharmacologic agents used for rapid tranquilization of emergency department patients with acute agitation or excited delirium. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.Y.L.; Taylor, D.M.; Kong, D.C.M.; Knott, J.C.; Taylor, S.E.; Graudins, A.; Keijzers, G.; Kulawickrama, S.; Thom, O.; Lawton, L.; et al. Management of behavioural emergencies: a prospective observational study in Australian emergency departments. J. Pharm. Pr. Res. 2019, 49, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellings JA, Zarcone JR, Reese RM, Valdovinos MG, Marquis JG, Fleming KK, Schroeder SR. A crossover study of risperidone in children, adolescents and adults with mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006 Apr;36:401-11.

- Knott, J.C.; Taylor, D.M.; Castle, D.J. Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Intravenous Midazolam and Droperidol for Sedation of the Acutely Agitated Patient in the Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2006, 47, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.M.; Yap, C.Y.; Knott, J.C.; Taylor, S.E.; Phillips, G.A.; Karro, J.; Chan, E.W.; Kong, D.C.; Castle, D.J. Midazolam-Droperidol, Droperidol, or Olanzapine for Acute Agitation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 69, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskey M, Warnell F, Parr JR, Le Couteur A, McConachie H. Emotional and behavioural problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2013 Apr;43(4):851-9.

- Maw, S.S.; Haga, C. Effectiveness of cognitive, developmental, and behavioural interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder in preschool-aged children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M.; Marshall, D.; Simmonds, M.; Le Couteur, A.; Biswas, M.; Wright, K.; Rai, D.; Palmer, S.; Stewart, L.; Hodgson, R. Interventions based on early intensive applied behaviour analysis for autistic children: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Heal. Technol. Assess. 2020, 24, 1–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.L.; Sipes, M.; Fodstad, J.C.; Fitzgerald, M.E. Issues in the Management of Challenging Behaviours of Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. CNS Drugs 2011, 25, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billstedt, E.; Gillberg, I.C.; Gillberg, C. Autism in adults: symptom patterns and early childhood predictors. Use of the DISCO in a community sample followed from childhood. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattaz, C.; Michelon, C.; Munir, K.; Baghdadli, A. Challenging behaviours at early adulthood in autism spectrum disorders: topography, risk factors and evolution. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2018, 62, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).