Submitted:

15 October 2023

Posted:

16 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

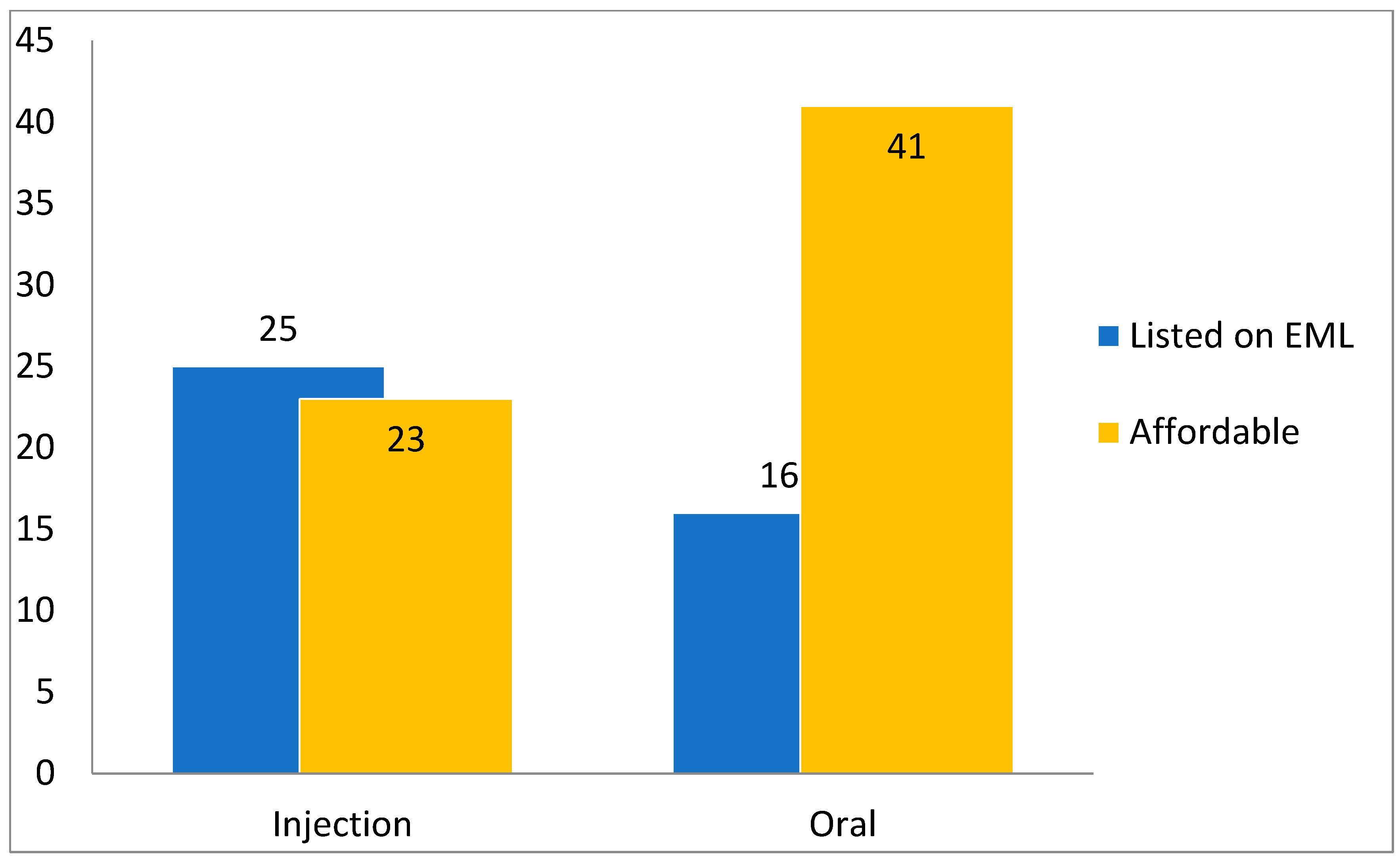

2.1. Affordability of the Antibiotics

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Sources of Data

- The WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics for evaluation and monitoring of use, 2023, which was downloaded from the 2023 AWaRe classification webpage of the WHO [4]. Information such as 2023 AWaRe classification of antibiotics, pharmacological class, and the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code of the antibiotics were extracted from this source.

- The 23rd List of Essential Medicines (EML) that was issued in 2023 [18] was utilized to determine the status of listing of each antibiotic (according to its dosage form and route of administration).

- An index that uses ATC codes to find each antibiotic’s Defined Daily Dose (DDD). The ATC/DDD index is a searchable version of the complete ATC index with DDDs provided online by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health [19].

- Drug information, prices, and leaflets webpage by Jordan Food and Drug Administration (JFDA) [20]. Prices of registered antibiotic items in all available packs for all marketing authorization holders in Jordan could be found by this official webpage.

4.2. Cost of DDD

4.3. Affordability

4.4. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Da Rocha Minarini, LA. , de Andrade, LN., De Gregorio, E., Grosso, F., Naas, T., Zarrilli, R. et al. Editorial: Antimicrobial Resistance as a Global Public Health Problem: How Can We Address It? Front Public Health. 2020 Nov 12;8:612844. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption: 2016-2018 early implementation. Geneva, 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-report-on-surveillance-of-antibiotic-consumption.

- Cox, JA. , Vlieghe, E., Mendelson, M., Wertheim, H., Ndegwa, L., Villegas, MV. et al. Antibiotic stewardship in low- and middle-income countries: the same but different? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017 Nov;23(11):812-818. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO AWaRe (access, watch, reserve) classification of antibiotics for evaluation and monitoring of use, 2023. In: The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: Executive summary of the report of the 24th WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, Geneva, 2023 (WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.04). Avaiable from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023. 24–28 April.

- World Health Organization. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book. Geneva, 2022. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/365135/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2022.02-eng.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial consumption in the EU/EEA (ESAC-Net)—Annual Epidemiological Report 2021. Stockholm, 2022. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/ESAC-Net_AER_2021_final-rev.

- Talaat, M. , Tolba, S., Abdou, E., Sarhan, M., Gomaa, M., Hutin, YJF. Over-Prescription and Overuse of Antimicrobials in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: The Urgent Need for Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs with Access, Watch, and Reserve Adoption. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Dec 8;11(12):1773. [CrossRef]

- Biro, A. , and Elek, P. The effect of primary care availability on antibiotic consumption in Hungary: a population based panel study using unfilled general practices. BMJ Open. 2019 Sep 13;9(9):e028233. [CrossRef]

- Rojas García, P. , and Antoñanzas Villar, F. Effects of economic and health policies on the consumption of antibiotics in a Spanish region. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020 Aug;20(4):379-386. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P. and Antoñanzas, F. Policies to Reduce Antibiotic Consumption: The Impact in the Basque Country. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Jul 19;9(7):423. [CrossRef]

- Nga, DTT., Chuc, NTK., Hoa, NP., Hoa, NQ., Nguyen, NTT., Loan, HT. et al. Antibiotic sales in rural and urban pharmacies in northern Vietnam: an observational study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014 Feb 20;15:6. [CrossRef]

- Costantini, S. and Walensky, RP. The Costs of Drugs in Infectious Diseases: Branded, Generics, and Why We Should Care. J Infect Dis. 2020 Feb 18;221(5):690-696. [CrossRef]

- Pulcini, C. , Beovic, B., Béraud, G., Carlet, J., Cars, O., Howard, P. et al. Ensuring universal access to old antibiotics: a critical but neglected priority. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017 Sep;23(9):590-592. [CrossRef]

- Making Medicines Affordable: A National Imperative. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Health Care Services, Committee on Ensuring Patient Access to Affordable Drug Therapies, in Nass, SJ., Madhavan, G., Augustine, NR. editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017 Nov 30. Chapter 1: The Affordability Conundrum.

- World Health Organization and Health Action International. Measuring medicine prices, availability, affordability and price components, 2nd edition. 2008. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/70013/WHO_PSM_PAR_2008.3_eng.pdf?

- Klein, EY. , Milkowska-Shibata, M., Tseng, KK., Sharland, M., Gandra, S., Pulcini, C. et al. Assessment of WHO antibiotic consumption and access targets in 76 countries, 2000-15: an analysis of pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Jan;21(1):107-115. [CrossRef]

- Versporten, A. , Zarb, P., Caniaux, I., Gros, MF., Drapier, N., Miller, M. et al. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob Health.. 2018 Jun;6(6):e619-e629. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines—23rd List, 2023. In: The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: Executive summary of the report of the 24th WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines, 24—. Geneva, 2023 (WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02). Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023. 28 April.

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology and Norwegian Institute of Public Health. ATC/DDD Index 2023. Oslo, 2023. Available from: https://www.whocc.

- Jordan Food and Drug Administration. Drug information, prices, and leaflets [accessed in Aug 2023]. Available from: http://www.jfda.jo/Pages/viewpage.aspx?pageID=184.

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology and Norwegian Institute of Public Health. DDD Definition and general considerations. Oslo, 2023. Available from: https://www.whocc.

- Gauthaman, J. and Jayanthi, M. Wide Cost Variations Observed in Antibiotics and Analgesics Prescribed for Dental Care in India: A Price and Affordability Analysis. Cureus. 2022 Jan 31;14(1):e21755. [CrossRef]

- Jordanian Ministry of Labor. The tertiary labor committee keeps the minimum wage limit. February 2023. Available from: https://mol.gov.jo/ar/NewsDetails/%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%84%d8%ac%d9%86%d8%a9_%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ab%d9%84%d8%a7%d8%ab%d9%8a%d8%a9_%d9%84%d8%b4%d8%a4%d9%88%d9%86_%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b9%d9%85%d9%84_%d8%aa%d8%a8%d9%82%d9%8a_%d8%b9%d9%84%d9%89_%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ad%d8%af_%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a3%d8%af%d9%86%d9%89_%d9%84%d9%84%d8%a3%d8%ac%d9%88%d8%b1.

- Abu-Ajaleh, S.; Darwish Elhajji, F.; Al-Bsoul, S.; Abu Farha, R.; Al-Hammouri, F.; Amer, A. An Evaluation of the Impact of Increasing the Awareness of the WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve (AWaRe) Antibiotics Classification on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Hospital Antibiotic Prescribing Practices. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azzam, S. , Mhaidat, NM., Banat, HA., Alfaour, M., Ahmad, DS., Muller, A. et al. An Assessment of the Impact of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic on National Antimicrobial Consumption in Jordan. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021 Jun 9;10(6):690. [CrossRef]

- Darwish Elhajji, F. , Al-Taani, GM., Anani, L., Al-Masri, S., Abdalaziz, H., Qabba’h, SH. et al. Comparative point prevalence survey of antimicrobial consumption between a hospital in Northern Ireland and a hospital in Jordan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Nov 12;18(1):849. [CrossRef]

- Abu Hammour, K. , Al-Heyari, E., Allan, A., Versporten, A., Goossens, H., Abu Hammour, G., et al. Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Jordan: Results of an Internet-Based Global Point Prevalence Survey. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020 Sep 13;9(9):598. [CrossRef]

| WHO AWaRe category | Antibiotic | ATC code | Listed on EML | DDD (g) | Mean cost (JOD/DDD) | Number of MAH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Amikacin | J01GB06 | Yes | 1 | 7.66 | 4 |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic-acid | J01CR02 | Yes | 3 | 4.45 | 3 | |

| Ampicillin | J01CA01 | Yes | 6 | 3.9 | 2 | |

| Benzathine-benzylpenicillin | J01CE08 | Yes | 3.6 | 4.67 | 1 | |

| Cefazolin | J01DB04 | Yes | 3 | 5.76 | 2 | |

| Clindamycin | J01FF01 | Yes | 1.8 | 14.89 | 3 | |

| Cloxacillin | J01CF02 | Yes | 2 | 4.65 | 1 | |

| Gentamicin | J01GB03 | Yes | 0.24 | 2.2 | 3 | |

| Metronidazole | J01XD01 | Yes | 1.5 | 4.75 | 8 | |

| Procaine-benzylpenicillin | J01CE09 | Yes | 0.6 | 2.54 | 1 | |

| Spectinomycin | J01XX04 | Yes | 3 | 5.93 | 1 | |

| Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | J01EE01 | Yes | 2 | 7.24 | 1 | |

| Watch | Azithromycin | J01FA10 | Yes | 0.5 | 8.03 | 3 |

| Cefepime | J01DE01 | No | 4 | 20.74 | 3 | |

| Cefotaxime | J01DD01 | Yes | 4 | 21.15 | 3 | |

| Cefoxitin | J01DC01 | No | 6 | 35.76 | 1 | |

| Ceftazidime | J01DD02 | Yes | 4 | 11.59 | 6 | |

| Ceftizoxime | J01DD07 | No | 4 | 33.58 | 2 | |

| Ceftriaxone | J01DD04 | Yes | 2 | 11.31 | 11 | |

| Cefuroxime | J01DC02 | Yes | 3 | 5.92 | 7 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | J01MA02 | Yes | 0.8 | 30.61 | 7 | |

| Clarithromycin | J01FA09 | Yes | 1 | 27.1 | 1 | |

| Delafloxacin | J01MA23 | No | 0.6 | 111.28 | 1 | |

| Ertapenem | J01DH03 | No | 1 | 24.18 | 2 | |

| Imipenem/cilastatin | J01DH51 | No | 2 | 31.91 | 5 | |

| Levofloxacin | J01MA12 | No | 0.5 | 13.94 | 6 | |

| Lincomycin | J01FF02 | No | 1.8 | 5.34 | 5 | |

| Meropenem | J01DH02 | Yes | 3 | 31.33 | 5 | |

| Moxifloxacin | J01MA14 | No | 0.4 | 16.15 | 3 | |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | J01CR05 | Yes | 14 | 30.75 | 4 | |

| Teicoplanin | J01XA02 | No | 0.4 | 7.73 | 5 | |

| Tobramycin | J01GB01 | No | 0.24 | 12.69 | 1 | |

| Vancomycin | J01XA01 | Yes | 2 | 18.74 | 9 | |

| Reserve | Ceftaroline-fosamil | J01DI02 | No | 1.2 | 72.47 | 1 |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | J01DD52 | Yes | 6 | 268.38 | 1 | |

| Ceftobiprole-medocaril | J01DI01 | No | 1.5 | 133.9 | 1 | |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | J01DI54 | No | 3 | 221.96 | 1 | |

| Colistin | J01XB01 | Yes | 9 | 63.03 | 1 | |

| Daptomycin | J01XX09 | No | 0.28 | 49.06 | 1 | |

| Linezolid | J01XX08 | Yes | 1.2 | 64.45 | 1 | |

| Oritavancin | J01XA05 | No | 1.2 | 609.93 | 1 | |

| Telavancin | J01XA03 | No | 0.75 | 93.6 | 1 | |

| Tigecycline | J01AA12 | No | 0.1 | 60.58 | 2 |

| WHO AWaRe category | Antibiotic | ATC code | Listed on EML 2023 | DDD (g) | Mean cost (JOD/DDD) | Number of MAH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Amoxicillin | J01CA04 | Yes | 1.5 | 0.46 | 12 |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic-acid | J01CR02 | Yes | 1.5 | 0.83 | 10 | |

| Ampicillin | J01CA01 | Yes | 2 | 0.46 | 4 | |

| Cefadroxil | J01DB05 | No | 2 | 1.37 | 6 | |

| Cefalexin | J01DB01 | Yes | 2 | 0.78 | 9 | |

| Clindamycin | J01FF01 | Yes | 1.2 | 1.66 | 5 | |

| Cloxacillin | J01CF02 | Yes | 2 | 0.78 | 2 | |

| Doxycycline | J01AA02 | Yes | 0.1 | 0.24 | 8 | |

| Flucloxacillin | J01CF05 | No | 2 | 0.83 | 1 | |

| Metronidazole | P01AB01 | Yes | 2 | 0.34 | 7 | |

| Ornidazole_oral | P01AB03 | No | 1.5 | 1.76 | 2 | |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | J01CE02 | Yes | 2 | 0.39 | 1 | |

| Secnidazole | P01AB07 | No | 2 | 3.38 | 1 | |

| Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | J01EE01 | Yes | 2 | 0.37 | 3 | |

| Tetracycline | J01AA07 | No | 1 | 0.24 | 1 | |

| Tinidazole | P01AB02 | No | 2 | 2.28 | 3 | |

| Watch | Azithromycin | J01FA10 | Yes | 0.3 | 0.72 | 16 |

| Cefaclor | J01DC04 | No | 1 | 1.19 | 8 | |

| Cefdinir | J01DD15 | No | 0.6 | 3.72 | 4 | |

| Cefditoren-pivoxil | J01DD16 | No | 0.4 | 1.97 | 1 | |

| Cefixime | J01DD08 | Yes | 0.4 | 2.41 | 10 | |

| Cefpodoxime-proxetil | J01DD13 | No | 0.4 | 2.9 | 5 | |

| Cefprozil | J01DC10 | No | 1 | 3.25 | 2 | |

| Cefuroxime | J01DC02 | Yes | 0.5 | 0.59 | 10 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | J01MA02 | Yes | 1 | 1.15 | 17 | |

| Clarithromycin | J01FA09 | Yes | 0.5 | 0.87 | 11 | |

| Delafloxacin | J01MA23 | No | 0.9 | 66.66 | 1 | |

| Erythromycin | J01FA01 | No | 2 | 0.58 | 2 | |

| Levofloxacin | J01MA12 | No | 0.5 | 1.46 | 14 | |

| Lincomycin | J01FF02 | No | 1.8 | 0.85 | 1 | |

| Lomefloxacin | J01MA07 | No | 0.4 | 1.29 | 1 | |

| Moxifloxacin | J01MA14 | No | 0.4 | 1.77 | 8 | |

| Norfloxacin | J01MA06 | No | 0.8 | 0.58 | 4 | |

| Ofloxacin | J01MA01 | No | 0.4 | 1.54 | 1 | |

| Pefloxacin | J01MA03 | No | 0.8 | 1.09 | 2 | |

| Rifabutin | J04AB04 | No | 0.15 | 2.91 | 1 | |

| Rifampicin | J04AB02 | No | 0.6 | 0.43 | 2 | |

| Rifaximin | A07AA11 | No | 0.6 | 1.57 | 1 | |

| Roxithromycin | J01FA06 | No | 0.3 | 0.76 | 5 | |

| Spiramycin | J01FA02 | No | 3 | 0.66 | 3 | |

| Fosfomycin | J01XX01 | No | 3 | 4.48 | 2 | |

| Minocycline | J01AA08 | No | 0.2 | 0.85 | 1 | |

| Reserve | Linezolid | J01XX08 | Yes | 1.2 | 45.98 | 4 |

| WHO AWaRe category | Antibiotic | Cost range (JOD/DDD) | Cost ratio | % Cost variation | Affordable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Amikacin | 6.15–8.83 | 1.44 | 43.6 | Yes |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic-acid | 3.27–5.58 | 1.71 | 70.6 | Yes | |

| Ampicillin | 2.99–4.91 | 1.64 | 64.2 | Yes | |

| Benzathine-benzylpenicillin | 4.67 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Cefazolin | 4.70–6.48 | 1.38 | 37.9 | Yes | |

| Clindamycin | 6.09–19.20 | 3.15 | 215.3 | Yes | |

| Cloxacillin | 4.03–5.27 | 1.31 | 30.8 | Yes | |

| Gentamicin | 1.11–3.78 | 3.41 | 240.5 | Yes | |

| Metronidazole | 3.26–9.14 | 2.80 | 180.4 | Yes | |

| Procaine-benzylpenicillin | 2.54 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Spectinomycin | 5.93 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | 7.24 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Watch | Azithromycin | 5.24–10.62 | 2.03 | 102.7 | Yes |

| Cefepime | 14.64–25.40 | 1.73 | 73.5 | No | |

| Cefotaxime | 11.92–24.24 | 2.03 | 103.4 | No | |

| Cefoxitin | 35.76 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Ceftazidime | 6.88–18.56 | 2.70 | 169.8 | Yes | |

| Ceftizoxime | 22.90–37.44 | 1.63 | 63.5 | No | |

| Ceftriaxone | 2.98–20.20 | 6.78 | 577.9 | Yes | |

| Cefuroxime | 3.39–10.12 | 2.99 | 198.5 | Yes | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 11.96–56.34 | 4.71 | 371.1 | Yes | |

| Clarithromycin | 27.10 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Delafloxacin | 111.28 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Ertapenem | 18.69–29.66 | 1.59 | 58.7 | No | |

| Imipenem/cilastatin | 25.00–39.68 | 1.59 | 58.7 | No | |

| Levofloxacin | 7.30–22.94 | 3.14 | 214.2 | Yes | |

| Lincomycin | 4.68–6.66 | 1.42 | 42.3 | Yes | |

| Meropenem | 16.69–57.11 | 3.42 | 242.2 | No | |

| Moxifloxacin | 7.20–22.19 | 3.08 | 208.2 | Yes | |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 25.13–36.69 | 1.46 | 46.0 | No | |

| Teicoplanin | 3.69–12.40 | 3.36 | 236.0 | Yes | |

| Tobramycin | 12.69 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Vancomycin | 8.01–29.28 | 3.66 | 265.5 | Yes | |

| Reserve | Ceftaroline-fosamil | 72.47 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 268.38 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Ceftobiprole-medocaril | 133.90 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Ceftolozane/tazobactam | 221.96 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Colistin | 59.72–66.33 | 1.11 | 11.1 | No | |

| Daptomycin | 49.06 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Linezolid | 61.06–67.84 | 1.11 | 11.1 | No | |

| Oritavancin | 609.93 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Telavancin | 93.60 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Tigecycline | 51.66–69.50 | 1.35 | 34.5 | No |

| WHO AWaRe category | Antibiotic | Cost range (JOD/DDD) | Cost ratio | % Cost variation | Affordable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Amoxicillin | 0.13–0.77 | 5.92 | 492.3 | Yes |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic-acid | 0.61–1.29 | 2.11 | 111.5 | Yes | |

| Ampicillin | 0.30–0.79 | 2.63 | 163.3 | Yes | |

| Cefadroxil | 0.85–2.48 | 2.92 | 191.8 | Yes | |

| Cefalexin | 0.29–1.22 | 4.21 | 320.7 | Yes | |

| Clindamycin | 1.38–2.00 | 1.45 | 44.9 | Yes | |

| Cloxacillin | 0.67–0.83 | 1.24 | 23.9 | Yes | |

| Doxycycline | 0.17–0.35 | 2.06 | 105.9 | Yes | |

| Flucloxacillin | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Metronidazole | 0.19–0.69 | 3.63 | 263.2 | Yes | |

| Ornidazole_oral | 1.56–1.95 | 1.25 | 25.0 | Yes | |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Secnidazole | 3.01–3.75 | 1.25 | 24.6 | Yes | |

| Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | 0.21–0.63 | 3.00 | 200.0 | Yes | |

| Tetracycline | 0.21–0.26 | 1.24 | 23.8 | Yes | |

| Tinidazole | 2.09–2.78 | 1.33 | 33.0 | Yes | |

| Watch | Azithromycin | 0.47–0.90 | 1.91 | 91.5 | Yes |

| Cefaclor | 0.78–1.43 | 1.83 | 83.3 | Yes | |

| Cefdinir | 3.40–4.47 | 1.31 | 31.5 | Yes | |

| Cefditoren-pivoxil | 1.97 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Cefixime | 1.19–3.12 | 2.62 | 162.2 | Yes | |

| Cefpodoxime-proxetil | 2.30–3.83 | 1.67 | 66.5 | Yes | |

| Cefprozil | 3.00–3.66 | 1.22 | 22.0 | Yes | |

| Cefuroxime | 0.38–0.78 | 2.05 | 105.3 | Yes | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.45–2.38 | 5.29 | 428.9 | Yes | |

| Clarithromycin | 0.55–1.32 | 2.40 | 140.0 | Yes | |

| Delafloxacin | 66.66 | 1.00 | 0.0 | No | |

| Erythromycin | 0.31–0.80 | 2.58 | 158.1 | Yes | |

| Levofloxacin | 0.62–1.81 | 2.92 | 191.9 | Yes | |

| Lincomycin | 0.75–0.94 | 1.25 | 25.3 | Yes | |

| Lomefloxacin | 1.14 | 1.26 | 26.3 | Yes | |

| Moxifloxacin | 1.01–2.17 | 2.15 | 114.9 | Yes | |

| Norfloxacin | 0.50–0.73 | 1.46 | 46.0 | Yes | |

| Ofloxacin | 1.41–1.66 | 1.18 | 17.7 | Yes | |

| Pefloxacin | 1.03–1.13 | 1.10 | 9.7 | Yes | |

| Rifabutin | 2.91 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Rifampicin | 0.41–0.47 | 1.15 | 14.6 | Yes | |

| Rifaximin | 1.57 | 1.00 | 0.0 | Yes | |

| Roxithromycin | 0.67–0.83 | 1.24 | 23.9 | Yes | |

| Spiramycin | 0.380.96 | 2.53 | 152.6 | Yes | |

| Fosfomycin | 3.78–5.17 | 1.37 | 36.8 | Yes | |

| Minocycline | 0.73–0.96 | 1.32 | 31.5 | Yes | |

| Reserve | Linezolid | 29.70–82.50 | 2.78 | 177.8 | No |

| Access | Watch | Reserve | Sig. (ρ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 28 | 47 | 11 | |

| Mean JOD/DDD (S.E.) | 3.03 (0.61) | 13.11 (2.94) | 153.03 (50.81) | <0.001* |

| Mean MAHs (S.E.) | 3.75 (0.60) | 4.74 (0.60) | 1.36 (0.28) | 0.003* |

| Affordable (%) | 28 (100.0%) | 36 (75.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.001** |

| Affordable | Non-affordable | Sig. (ρ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 64 | 22 | |

| Mean MAH (S.E.) | 4.69 (0.50) | 1.95 (0.30) | 0.001* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).