Submitted:

14 October 2023

Posted:

17 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Objectives and methodology

3. Results

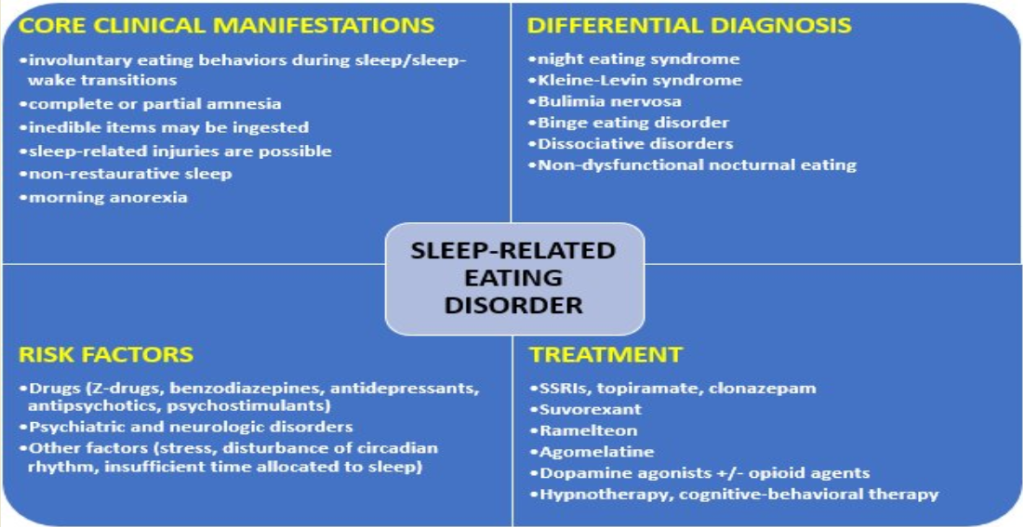

3.1. Risk factors for SRED onset

3.1.1. The drug-induced SRED

| Reference | Type of paper | Main outcomes | Results and observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [28] | Review (N=148 patients) |

Incidence of drug-induced SRED | Zolpidem-induced complex sleep behaviors (N=79 patients from case reports and case series, N=69 patients from 1454 patients treated with zolpidem in three observational clinical studies); 88% of cases were found to be probably associated with zolpidem |

| [29] | Case series (N=2 Malay women) |

Evolution of drug-induced SRED | Quetiapine may induce SRED at various doses, ranging from 50 to 200 mg/day |

| [30] | Review | Evolution of drug-induced SRED | Triazolam, lithium, olanzapine, risperidone, zopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem ER may be associated with new-onset SRED cases |

| [31] | Review (n=10 reports, N=17 patients) | Onset of SRED and other sleep-related behaviors | Zolpidem>zopiclone, zalepon |

| [32] | Retrospective study (N=676 AE reports) | Drug-associated SRED cases | Zolpidem (36%)>sodium oxybate (27%)>quetiapine (14%); aripiprazole may be associated with SRED episodes (3.6%); SNRIs antidepressants also determined SRED episodes (2.7% for duloxetine, 2.1% for venlafaxine); psychostimulants (0.4-1.5%) may associate new onset SRED cases |

| [33] | Retrospective study (N=5784 AE reports) | Drug-associated SRED and somnambulism | 508 SRED cases out of 5784 reports of SRED and somnambulism; quetiapine also was associated with SRED in >53% of these reports |

| [34] | Cross-sectional study (N=1318 patients taking hypnotics) | Drug-associated SRED | 8.4% presented new-onset SRED, especially young subjects, ↑doses of DZP-equivalent doses, ↑PSQI scores |

| [35] | Retrospective study (n=125 patients) | Sleep-related behaviors in patients with MDD, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorders, somatoform disorders, or sleep disorders, treated with hypnosedatives | ~15% presented complex sleep-related behaviors, all were treated with zolpidem (over 10 mg/day) |

| [36] | Review (n=40 case reports) |

SRED onset | Zolpidem (≥10 mg/day) use was associated with SRED |

| [37] | Case series (N=8 patients) |

SRED onset in patients treated with zolpidem | Zolpidem triggered SRED behaviors (1-8 episodes/night) |

| [38] | Case report (Caucasian woman, 53-year-old) | SRED onset and evolution | Zolpidem-induced SRED episodes (2-3 episodes/week) and weight increase (6 kg after 12 months) |

| [39] | Case report (African-American woman, 51-year-old) | SRED onset and evolution | Zolpidem IR triggered the onset of sleepwalking, SRED, and sleep-driving |

| [40] | Case series (N=5 patients) |

Nocturnal eating behaviors | Zolpidem determined SRED and these behaviors disappeared after the drug’s discontinuation |

| [41] | Case report (a 45-year-old man) |

SRED behaviors | Zolpidem determined night eating and cooking activities |

| [42] | Case report (a 46-year-old woman) | SRED behaviors | Zolpidem was administered for insomnia and induced amnestic nocturnal eating behaviors. Switching to eszopiclone led to the complete remission of SRED. |

| [43] | Case report (a 45-year-old man) | SRED onset and evolution | Sleepwalking and nocturnal eating behaviors followed by complete amnesia appeared after zolpidem CR was administered; symptoms disappeared after stopping zolpidem use |

| [44] | Case report (a 71-year-old Korean man) |

SRED onset and evolution | Zolpidem CR triggered SRED and other sleep-related complex behaviors; these symptoms disappeared once zolpidem was stopped |

| [45] | Case report (a 49-year-old man) | SRED onset and evolution | Lamotrigine + clonazepam + zolpidem was the combination used to treat this patient with BD; SRED behaviors appeared after the initiation of zolpidem and disappeared when this drug was discontinued |

| [46] | Case report (a 21-year-old woman) | SRED onset and evolution | This patient was diagnosed with ADHD and zolpidem was associated with SRED behaviors, which disappeared after this drug’s discontinuation and replacement by clonazepam |

| [47] | Case series (N=2 patients) |

SRED onset and evolution | Zolpidem ER 12.5 mg/day led to amnestic night-eating behaviors; switching on zolpidem IR led to the remission of these behaviors |

| [48] | Case report (a 49-year-old woman) | SRED onset and evolution | This patient was diagnosed with MDD and received treatment with duloxetine and zolpidem up to 15 mg/day; SRED appeared and a switch on zaleplon 10 mg/day was initiated, but SRED and NES episodes persisted; zaleplon discontinuation led to the remission of night eating behaviors |

| [49] | Case report (a 48-year-old Japanese woman) |

SRED onset and evolution | Triazolam administration led to SRED behaviors; a dose decrease was followed by a reduced frequency of SRED episodes |

| [24,50] | Case series (N=19 patients) |

SRED onset and evolution | Nocturnal eating appeared immediately after triazolam abuse, and its discontinuation led to symptoms’ remission; amitriptyline (200 mg/day) caused might-eating behaviors that disappeared after drug’s discontinuation |

| [51] | Case report (a 9-year-old boy) |

SRED onset and evolution | This patient was diagnosed with severe ADHD, clonus dystonia, and insomnia, and clonazepam (0.5 mg/day) was initiated; SRED appeared rapidly after clonazepam administration, and the discontinuation of this drug led to complete SRED remission |

| [52] | Case report (a 42-year-old man) | SRED onset and evolution | Sodium oxybate (4.5-8 g/night) initiated for narcolepsy-cataplexy led to the onset of complex activities during sleep, SRED included; these symptoms disappeared after the dose was reduced to 7 g/night |

| [53] | Case report (a 51-year-old woman) | SRED behaviors in a patient with schizophrenia | Haloperidol determined RLS, SRED and NES |

| [54] | Case report (a 52-year-old man) | SRED in a patient with type I BD | Olanzapine (10 mg/day) added to lithium was responsible for sleepwalking and nocturnal eating episodes with complete amnesia; olanzapine’s discontinuation reversed these episodes |

| [55] | Case report (a 41-year-old Japanese man) | SRED onset in a patient with MDD | Aripiprazole (10 mg/day) added to sertraline led to the onset of SRED episodes; reducing the dose to 1.5 mg/day led to the rapid and complete remission of night eating behaviors |

| [56] | Case report (a 48-year-old woman) | SRED in a patient with rapid-cycling BD | Quetiapine at bedtime (100 mg) led to the onset of somnambulism and nocturnal eating followed by amnesia |

| [57] | Case series (N=2 patients) |

SRED onset in patients with OSA | Quetiapine-induced sleepwalking and SRED-like behaviors; quetiapine discontinuation + CPAP therapy led to these symptoms remission |

| [58] | Case report (a 68-year-old man) | SRED onset in a patient with vascular dementia+ psychotic symptoms | Risperidone (2 mg/day) determined the onset of nocturnal eating behaviors + complete amnesia; these symptoms disappeared when the dose decreased to 1 mg/day |

| [59] | Case report (a 16-year-old girl) | SRED onset and evolution | Risperidone (1 mg/day) led to the onset of SRED behaviors, including dangerous cooking activities; after risperidone was stopped, these eating behaviors disappeared |

| [60] | Case report (a 28-year-old white male) | SRED onset in a patient with schizoaffective disorder | Ziprasidone (120 mg/day) induced sleepwalking and SRED; decreasing the dose to 40 mg/day led to the disappearance of SRED; re-challenging with 120 mg/day led to the re-appearance of SRED. |

| [61] | Case report (a 24-year-old woman) | SRED onset in a patient with MDD | Fluoxetine (40 mg/day) + trazodone (75 mg/day) + zolpidem (10 mg/day) triggered episodes of nocturnal binge eating with amnesia; switching to mirtazapine (30 mg/day) and clonazepam (0.25 mg/day) led to the transient remission of SRED, but only the complete discontinuation of this antidepressant allowed for the disappearance of SRED |

| [62] | Case report (a 19-year-old woman) | SRED onset in a patient with anxiety, depressed mood, and suicidal ideation | Mirtazapine (30 mg/day) led to the development of SRED episodes; these manifestations remitted when the dose was decreased to 15 mg |

| [63] | Case report (a 33-year-old white man) | SRED in a patient with nicotine use disorder | Bupropion SR (300 mg/day) induced nocturnal eating episodes, sleepwalking, and telephone use with partial/complete amnesia; these episodes disappeared after the antidepressant’s discontinuation |

| [64] | A case-control study (N=100 patients with RLS and 100 matched controls) | SRED onset in patients with RLS | A trend toward the association of dopaminergic agents or hypnotic drugs with SRED in this population was reported (p=0.20) |

| [65] | Expert opinion | SRED in patients with RLS or PD | L-dopa/carbidopa and bromocriptine may be associated with new-onset SRED cases |

3.1.2. Psychiatric and organic disorders as potential risk factors for SRED

| Reference | Type of paper | Main outcomes | Results and observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [24,66] | Review + a 5-year study (N=19 participants) | Risk factors for SRED | Depression severity, dissociative symptoms, SUDs; daytime eating disorder, NES, other sleep disorders |

| [50] | Case series (N=19 patients) | Risk factors for SRED (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) | OSA, PLM, familial sleepwalking, and irregular sleep/wake pattern disorder, familial RLS, anorexia nervosa with nocturnal bulimia, and migraines treated with amitriptyline were associated with SRED and NES behaviors; acute stress derived from worries about the safety of family members or relationships problems may trigger SRED |

| [30] | Narrative review | Risk factors for SRED | Other sleep disorders can be considered a risk factor for SRED |

| [23] | Survey-based study (N=130 patients) | Risk factors for NES and SRED | RLS is frequently related to SRED, possibly mediated by mistreatment with sedative agents |

| [36] | Review (n=40 case reports) |

Risk factors for SRED | OSA, MDD, and RLS were the most frequent disorders reported in patients with SRED |

| [67] | Survey-based study (N=53 patients) | Risk factors for SRED in a group of patients with sleep disorders | 66% of the responders had frequent night-eating behaviors, 45% had SRED |

| [64] | A case-control study (N=100 patients) | Risk factors for SRED in patients with RLS | RLS was associated more frequently with SRED than the control group; ↑MOCI scores in patients with both RLS and SRED |

| [68] | Cross-sectional study (N=120 patients) | SRED and NES in patients with RLS | SRED or NES were detected more frequently in patients with RLS than in the general population |

| [69] | Case report (a 34-year-old white man) | SRED onset and evolution | OSA and SRED can be frequently detected together; OSA may precipitate the onset of SRED |

| [70] | Case series (N=2 patients) | SRED onset and evolution | Narcolepsy and OSA may be predisposing factors for SRED; work-related stress, disturbance of the circadian rhythm due to professional tasks, and insufficient time allocated to sleep were reported as risk factors for SRED |

| [71] | Cross-sectional study (N=65 patients) | SRED in patients with narcolepsy vs. healthy controls | Narcolepsy and cataplexy were more frequently associated with SRED; ↑severity of depression, in females, and higher scores of bulimia and social insecurity on EDI-2, ↑MOCI scores |

| [72] | A controlled study (N=36 patients) | SRED vs. sleepwalking profiles | A personal history of eating problems in childhood and ↑current anorexia scores were reported in patients with SRED/sleepwalking vs. healthy controls |

| [73] | A case series (N=2 patients) | SRED in patients with PD | OSA, NES, and REM sleep disorders were present as comorbidities; |

| [74] | Case report (a 56-year-old woman) | SRED in a patient with PD | SRED was detected together with PD, OSA, sleepwalking, depression, and REM sleep parasomnia |

3.1.3. Other factors associated with risk of SRED onset

3.2. Comorbidities of SRED

3.3. Pathogenesis of SRED

3.4. Differential diagnosis

3.5. Epidemiology

3.6. Structured evaluation

3.7. Treatment

| Reference | Type of paper | Main outcomes | Results and observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [10] | Expert opinion | The efficacy of pharmacological interventions in patients with SRED | Pramipexole was efficient in SRED + RLS cases; sleepwalking + SRED may benefit from low doses of clonazepam; regular follow-up is recommended for all patients with SRED at least 2-3 times/year; first-line treatment for SRED includes SSRIs, with topiramate and clonazepam as alternative |

| [11] | Expert opinion | The efficacy of treatments for DOAs | Removal of precipitating factors and prevention |

| [24] | Case series (N=19 patients) | Clinical evolution and polysomnographic data in SRED patients undergoing various therapeutic approaches | Adequate treatment of comorbid disorders and vulnerabilities |

| [49] | Case report (a 48-year-old Japanese woman |

Evolution of SRED symptoms during treatment | Pramipexole 0.125 mg + clonazepam improved SRED, RLS, and sleepwalking |

| [53] | Case report (a 51-year-old woman) |

Evolution of SRED symptoms during treatment | Clonazepam completely eliminated the RLS episodes and nocturnal eating |

| [50,87,103] | Case series (N=19 patients) + two reviews | Evolution of SRED symptoms during various therapeutic interventions | CPAP for SRED + OSA, evidence is sparse; fluoxetine was efficient; targeting the primary sleep disorder is essential; carbidopa/l-dopa, bromocriptine +/- codeine in SRED + sleepwalking or PLM |

| [69] | Case report (a 34-year-old white man) |

Effect of limited offering of food during nighttime | The effect of this intervention was favorable |

| [70] | Case series (N=2 patients) |

SRED evolution during pharmacological treatment | Sertraline (25 mg/day) induced SRED symptoms’ remission |

| [75] | Controlled trial (N=11 patients) |

The efficacy of pramipexole on clinical and actigraphic parameters in patients with SRED | Pramipexol (0.18-0.36 mg/day) was efficient in decreasing the median night duration of SRED; the tolerability was good |

| [85] | Case report (a 29-year-old man) |

Effect of limited offering of food before going to bed | The effect of this intervention was favorable |

| [104] | Review + expert opinion | Considerations on the treatment of NES and SRED |

None of the explored treatment options for NES/SRED had long-term efficacy in good-quality trials |

| [105] | Case series (N=7 cases) |

Pharmacological treatment of SRED | Dopaminergic + opioid agents +/- sedative agents prn were efficient |

| [106] | Case report (a 35-year-old Caucasian man) |

The efficacy of pharmacological treatment in a patient with obesity and SRED | Phentermine + topiramate ER was well tolerated and efficient |

| [107] | RCT (N=34 patients) | SRED evolution during treatment with topiramate vs. placebo | Topiramate (up to 300 mg/day) decreased the episodes of SRED |

| [108] | Clinical study (N=17 patients) | The efficacy and tolerability of topiramate in the treatment of SRED | Topiramate was efficient and well-tolerated |

| [109] | Case series (N=4 patients) |

SRED and NES evolution during topiramate treatment | Topiramate was efficient at doses of 100 mg/day |

| [110] | Case report (a 45-year-old woman) |

Efficacy of topiramate in a patient with sleepwalking, SRED, sleep-related smoking, and mild OSA | Topiramate (100 mg/day) led to the complete resolution of dysfunctional nocturnal behaviors |

| [111] | Retrospective chart review (N=30 patients) |

SRED evolution determined by CGI-I scores during topiramate treatment | 68% were responders after 11.6 months of treatment; AEs were reported by 84% of the participants, and 40% discontinued the treatment |

| [112] | Case report (a 28-year-old man) |

SRED and sleepwalking symptoms evolution during pharmacological treatment | Clonazepam (2 mg/day) + fluoxetine (20 mg/day) failed to control sleep-related behaviors, but topiramate (50 mg/day) was successful; the tolerability was good |

| [113] | Case series (N=4 patients) | The effects of SSRIs on the nocturnal eating/drinking disorder | Fluvoxamine and paroxetine were efficient for SRED symptoms |

| [114] | Case report (a 54-year-old white woman) |

The effects of antidepressants on SRED | Agomelatine controlled sleep-related eating symptoms, but when the drug was discontinued, SRED symptoms re-appeared |

| [115] | Case series (N=2 patients) | Efficacy of treatment in patients with SRED, monitored with polysomnography | The combination of bupropion + l-dopa + trazodone led to good results in patients with SRED |

| [116] | Case report (a 25-year-old woman) |

Efficacy of treatment orexin antagonists in SRED | Suvorexant was efficient in a patient diagnosed with depression and SRED |

| [117] | Retrospective study (N=49 patients) | Efficacy of pharmacological treatment in patients with SRED | Ramelteon (4-8 mg/day) as an add-on to the ongoing benzodiazepine treatment was followed by a dose reduction of benzodiazepine and this was an efficient strategy |

| [118] | A 5-year follow-up study (N=36 patients, adults and children) |

Efficacy of hypnotherapy (two sessions) in patients with parasomnias | Only two patients presented SRED, but the overall rate of response was good |

| [119] | Case report (a 38-year old woman) |

Efficacy of hypnotherapy in a patient with SRED and sleepwalking | The episodes of SRED/sleepwalking decreased significantly |

| [120,121] | Retrospective study (N=46 patients) + a literature review of nonpharmacological treatments for parasomnias | The efficacy of five outpatient CBT-NREMP sessions | CBT-NREMP was efficient in decreasing the severity of NREM parasomnia, insomnia, and anxiety and depression severity; the significance for SRED is uncertain due to the low representation of this pathology in the study sample (1.6%) |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walsh, B.T. The importance of eating behavior in eating disorders. Physiol Behav 2011, 104, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, O. An integrative model as a step toward increasing the awareness of eating disorders in the general population. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1184932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grave, R.D. Eating disorders: Progress and challenges. Eur J Intern Med 2011, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsley, R.; Ahokas, A.; Suarez, A.; Marinescu, D.; Doci, I.; Lehtmets, A.; et al. Efficacy of tianeptine 25-50 mg in elderly patients with recurrent major depressive disorder: An 8-week placebo- and escitalopram-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2018, 79, 17m11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, O. Is fecal microbiota transplantation a useful therapeutic intervention for psychiatric disorders? A narrative review of clinical and preclinical evidence. Curr Med Res Opin 2023, 39, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P. Current approach to eating disorders: A clinical update. Intern Med J 2020, 50, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, O. Esketamine for treatment-resistant depression: A review of clinical evidence. Exp Ther Med 2023, 25, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (Revised-3): Diagnostic and Coding Manual; American Academy of Sleep Medicine,: Darien, IL, USA, 2014; pp. 240–245. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, text revised. Arlington, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022.

- Chiaro, G.; Caletti, M.T.; Provini, F. Treatment of sleep-related eating disorder. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2015, 17, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idir, Y.; Oudiette, D.; Arnulf, I. Sleepwalking, sleep terrors, sexsomnia and other disorders of arousal: The old and the new. J Sleep Res 2022, e13596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaioni, M.; Scarpelli, S.; Gorgoni, M.; Alfonsi, V.; De Gennaro, L. EEG patterns prior to motor activations of parasomnias: A systematic review. Nat Sci Sleep 2021, 13, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, H.; Joncas, S.; Zadra, A.; Montplaisir, J. Dynamics of slow-wave activity during the NREM sleep of sleepwalkers and control subjects. Sleep 2000, 23, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deseilles, M.; Dang-Vu, T.; Schabus, M.; Sterpenich, V.; Maquet, P.; Schwartz, S. Neuroimaging insights into the pathophysiology of sleep disorders. Sleep 2008, 31, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, S.; Soucy, J.P.; Gravel, P.; Michaud, M.; Postuma, R.; Massicotte-Marquez, J.; et al. Assessing whole brain perfusion changes in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2006, 67, 1618–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenck, C.H.; Bundlie, S.R.; Mahowald, M.W. Delayed emergence of a parkinsonian disorder in 38% of 29 older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Neurology 1996, 46, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (Revised-2): Diagnostic and Coding Manual; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Rochester, MN, USA, 2005; pp. 174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.P.; Anees, S.; Thorpy, M.J. Pathophysiology, associations, and consequences of parasomnias. In Encyclopedia of Sleep, 1st ed.; Kushida, C.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 4, pp. 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). Available online at https://icd.who.int/ (accessed 01 July 2023). /: statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). Available online at https, 01 July.

- World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. World Health Organization, 1993. Revised 2023. Available online at https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/G00-G99/G40-G47/G47-/G47.69 (accessed 07 July 2023). /.

- Stunkard, A.J.; Grace, W.J.; Wolff, H.G. The night-eating syndrome: A pattern of food intake among certain obese patients. Am J Med 1955, 19, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekbom, K.A. Restless legs syndrome. Neurology 1960, 10, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.J.; Schenck, C.H. Restless nocturnal eating: A common feature of Willis-Ekbom syndrome (RLS). J Clin Sleep Med 2012, 8, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.H.; Hurwitz, T.D.; Bundlie, S.R.; Mahowald, M.W. Sleep-related eating disorders: Polysomnographic correlates of a heterogeneous syndrome distinct from daytime eating disorders. Sleep 1991, 14, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J.; Kavey, N.B. Somnambulistic eating: A report of three cases. Intl J Eat Disord 1990, 9, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaami, S,; Graziano, S. ; Tittarelli, R.; Beck, R.; Marinelli, E. BZDs, designer BZDs and Z-drugs: Pharmacology and misuse insights. Curr Pharm Des 2022, 28, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, G.; Liao, V.W.Y.; Ahring, P.K.; Chebib, M. The Z-drugs zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone have varying actions on human GABA-A receptors containing γ1, γ2 and γ3 subunits. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 599812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, N.; Mittal, R.; Gupta, M.C. Systematic literature review on zolpidem-induced complex sleep behaviors. Indian J Psychol Med 2021, 43, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagasundram, S. Quetiapine-induced sleep-related eating disorder: A case report. Clin Case Rep 2021, 9, e04168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, M.; Schenck, C.H.; Howell, M.J. NonREM disorders of arousal and related parasomnias: An updated review. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolder, C.R.; Nelson, M.H. Hypnosedative-induced complex behaviours: Incidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs 2008, 22, 1021–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, D.; Gérard, A.O.; van Obberghen, E.K.; Othman, N.B.; Ettore, E.; Giordana, B.; et al. Medications as a trigger of sleep-related eating disorder: A disproportionality analysis. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouverneur, A.; Ferreira, A.; Morival, C.; Pageot, C.; Tournier, M.; Pariente, A. A safety signal of somnambulism with the use of antipsychotics and lithium: A pharmacovigilance disproportionality analysis. British J Clin Pharmacol 2021, 87, 3971–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaesu, Y.; Ishikawa, J.; Komada, Y.; Murakoshi, A.; Futenma, K.; Nishida, S.; Inoue, Y. Prevalence of and factors associated with sleep-related eating disorder in psychiatric outpatients taking hypnotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2016, 77, e892–e898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.J.; Ni, H.C.; Chen, H.C.; Lin, Y.T.; Liao, S.C. Risk predictors for hypnosedative-related complex sleep behaviors: A retrospective, cross-sectional pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry 2010, 71, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.; Jimenez, A.; Sanchez, I.; Seeger, C.; Joseph, M. Sleep-related eating disorder associated with zolpidem: Cases compiled from a literature review. Sleep Med X 2022, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valiensi, S.M.; Cristiano, E.; Martinez, O.A.; Reisin, R.C.; Alvarez, F. Sleep related eating disorders as a side effect of zolpidem. Medicina (B Aires) 2010, 70, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Nzwalo, H.; Ferreira, L.; Peralta, R.; Bentes, C. Sleep-related eating disorder secondary to zolpidem. BMJ Case Rep 2013, 2013, bcr2012008003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, R.; Chesson, A.L. Jr. Zolpidem-induced sleepwalking, sleep related eating disorder, and sleep-driving: Fluorine-18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography analysis, and a literature review of other unexpected clinical effects of zolpidem. J Clin Sleep Med 2009, 5, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenthaler, T.I.; Silber, M.H. Amnestic sleep-related eating disorder associated with zolpidem. Sleep Med 2022, 3, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.H.; Ji, K.H. Zolpidem-induced sleep-related eating disorder. J Neurol Sci 2010, 288, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, M. Zolpidem and amnestic sleep related eating disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 2007, 3, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.; Garg, G.; Rataboli, P.V. Zolpidem induced nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder (NSRED) in a male patient. Int J Eat Disord 2009, 42, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Shin, H.W. Zolpidem induced sleep-related eating and complex behaviors in a patient with obstructive sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2016, 14, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Seijas, D.; Castillo, J.L.; Perez, C.J. Zolpidem induced sleep related eating disorder. Rev Med Chil 2010, 138, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Furuhashi, Y. Unexpected effect of zolpidem in a patient with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Asian J Psychiatr 2019, 44, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, A.; Krystal, A. Report of two cases where sleep related eating behavior occurred with the extended-release formulation but not the immediate-release formulation of a sedative-hypnotic agent. J Clin Sleep Med 2008, 4, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, S.; Joshi, K.G. A case of zaleplon-induced amnestic sleep-related eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2010, 71, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Yoshimura, R.; Takano, M. Successful treatment with clonazepam and pramipexole of a patient with sleep-related eating disorder associated with restless legs syndrome: A case report. Case Rep Med 2012, 2012, 893681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, C.H.; Hurwitz, T.D.; O’Connor, K.A.; Mahowald, M.W. Additional categories of sleep-related eating disorders and current status of treatment. Sleep 1993, 16, 457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Petrarca, A.M.; Khudro, A.L. Sleep-related eating disorder (SRED): Paradoxical effect of clonazepam. J Clin Sleep Med 2018, 14, 1261–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.M.; Maze, T.; Shafazand, S. Sodium oxybate-induced sleep driving and sleep-related eating disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 2011, 7, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, J.; Yamashita, H.; Mizuno, S.; Kuramoto, Y.; Kagaya, A.; Yamawaki, S.; Inami, Y. Nocturnal eating/drinking syndrome and neuroleptic-induced restless legs syndrome. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1999, 14, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Paquet, V.; Strul, J.; Servais, L.; Pelc, I.; Frossion, P. Sleep-related eating disorder induced by olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry 2002, 63, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Takano, M. Aripiprazole-induced sleep-related eating disorder: A case report. J Med Case Reports 2018, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathman, J.C.; Neal, D.W.; Thomas, C.R. Sleep-related eating disorder associated with quetiapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014, 34, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanna, S.; Ullah, M.I.; Pope, C.R.; Holloman, G.; Koch, C.A. Quetiapine-induced sleep-related eating disorder-like behavior: A case series. J Med Case Rep 2012, 6, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.L.; Shen, W.W. Sleep-related eating disorder induced by risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry 2004, 65, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneş, S.; Camkurt, M.A. Sleep-related eating disorder associated with risperidone: An adolescent case. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016, 36, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P. A case of sleepwalking with sleep-related eating associated with ziprasidone therapy in a patient with schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016, 36, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Bahk, W.M. Sleep-related eating disorder associated with mirtazapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2014, 34, 752–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinith, D.; Mathilakath, A.; Kim, D.I.; Patel, B. Sleep-related eating disorder with mirtazapine. BMJ Case Rep 2018, 2018, bcr2018224676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaal, Y.; Krenz, S.; Zullino, D.F. Bupropion-induced somnambulism. Addiction Biology 2003, 8, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provini, F.; Antelmi, E.; Vignatelli, L.; Zaniboni, A.; Naldi, G.; Calandra-Buonaura, G.; et al. Association of restless legs syndrome with nocturnal eating: A case-control study. Mov Disord 2009, 24, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirenberg, M.J.; Waters, C. Nocturnal eating in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2010, 25, 126–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, J.W.; Herzog, D.B.; Fava, M. The prevalence of sleep-related eating disorder in psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations. Psychol Med 1999, 29, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.J.; Schenck, C.H.; Larson, S.; Pusalavidyasagar, S. Nocturnal eating and sleep-related eating disorder (SRED) are common among patients with sleep-related eating disorder (SRED) are common among patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep 2010, 33, A227. [Google Scholar]

- Antelmi, E.; Vinai, P.; Pizza, F.; Marcatelli, M.; Speciale, M.; Provini, F. Nocturnal eating is part of the clinical spectrum of restless legs syndrome and an underestimated risk factor for increased body mass index. Sleep Med 2014, 15, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eveloff, S.E.; Millman, R.P. Sleep-related eating disorder as a cause of obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 1993, 104, 629–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; de Castro, J.R.; Liendo, C.; Schenk, C.H. Two cases of sleep-related eating disorder responding promptly to low-dose sertraline therapy. J Clin Sleep Med 2018, 14, 1805–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaia, V.; Poli, F.; Pizza, F.; Antelmi, E.; Franceschini, C.; Moghadam, K.K.; et al. Narcolepsy with cataplexy associated with nocturnal compulsive behaviors: A case-control study. Sleep 2011, 34, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brion, A.; Flamand, M.; Oudiette, D.; Voillery, D.; Golmard, J.L.; Arnulf, I. Sleep-related eating disorder versus sleepwalking: A controlled study. Sleep Med 2012, 13, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobeira Nato, M.A.; Pena Pereira, M.A.; Tavares Sobreira, E.S.; Nishigara Chagas, M.H.; Rodrigues, G.R.; França Fernandes, R.M.; et al. Sleep-related eating disorder in two patients with early-onset Parkinson’s disease. Eur Neurol 2011, 66, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Jahngir, M.U.; Siddiqui, J.H. Sleep-related eating disorder in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. Cureus 2018, 10, e3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provini, F.; Albani, F.; Vetrugno, R.; Vignatelli, L.; Lombardi, C.; Plazzi, G.; Montagna, P. A pilot double-blind pramipexole in sleep-related eating disorder. Eur J Neurol 2005, 12, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santin, J.; Mery, V.; Elso, M.J.; Retamal, E.; Torres, C.; Ivelic, J.; Godoy, J. Sleep-related eating disorder: A descriptive study in Chilean patients. Sleep Med 2014, 15, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, J.W. Clinical and polysomnographic features of sleep-related eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1998, 59, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.J. Restless eating, restless legs, and sleep related eating disorder. Curr Obes Rep 2014, 3, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soca, R.; Keenan, J.C.; Schenck, C.H. Parasomnia overlap disorder with sexual behaviors during sleep in a patient with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2016, 12, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu-Semenescu, S.; Maranci, J.B.; Lopez, R.; Drouot, X.; Dodet, P.; Gales, A.; et al. Comorbid parasomnias in narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia: More REM than NREM parasomnias. J Clin Sleep Med 2022, 18, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainieri, G.; Loddo, G.; Provini, F.; Nobili, L.; Manconi, M.; Castelnovo, A. Diagnosis and management of NREM sleep parasomnias in children and adults. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaszczyk, B.; Wieczorek, T.; Michalek-Zrabkowska, M.; Wieckiewicz, M.; Mazur, G.; Martynowicz, H. Polysomnography findings in sleep-related eating disorder: A systematic review and case report. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1139670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, Y. Sleep-related eating disorder and its associated conditions. Psychiatry Clinical Neurosciences 2015, 69, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perogamvros, L.; Baud, P.; Hasler, R.; Cloninger, C.R.; Schwartz, S.; Perrig, S. Active reward processing during human sleep: Insights from sleep-related eating disorder. Front Neurol 2012, 3, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, S.B.; Schenck, C.H. Sleep-related eating disorder in a 29 year-old man: A case report with diagnostic polysomnographic findings. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2007, 16, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrugno, R.; Manconi, M.; Ferini-Strambi, L.; Provini, F.; Plazzi, G.; Montagna, P. Nocturnal eating: Sleep-related eating disorder or night eating syndrome? A videopolysomnographic study. Sleep 2006, 29, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, J.W.; Johnson, E.A.; Richards, L.M. Sleep-related eating disorder. Handb Clin Neurol 2011, 98, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, L.; Haynes, L.C. What every nurse needs to know about nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2001, 39, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ocampo, J.; Foldvary, N.; Dinner, D.S.; Golish, J. Sleep-related eating disorder in fraternal twins. Sleep Medicine 2002, 3, 525–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, O.; Vasile, D.; Mangalagiu, A.G.; Petrescu, B.M.; Tudor, C.; Ungureanu, D.; Candea, C. Efficacy and tolerability of calcium channel alpha-2-delta ligands in psychiatric disorders. RJMM 2017, CXX, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinai, P.; Ferri, R.; Ferrini-Strambi, L.; Cardetti, S.; Anelli, M.; Vallauri, P.; et al. Defining the borders between sleep-related eating disorder and night eating syndrome. Sleep Med 2012, 13, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komada, Y.; Takaesu, Y.; Matsui, K.; Nakamura, M.; Nishida, S.; Kanno, M.; et al. Comparison of clinical features between primary and drug-induced sleep-related eating disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016, 12, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Albás, J.J.; de Entrambasaguas-Barreto, M. Kleine-Levin syndrome and sleep-related eating disorder. Rev Neurol 2003, 37, 200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Winkelman, J.W. Sleep-related eating disorder and night eating syndrome: Sleep disorders, eating disorders, or both? Sleep 2006, 29, 876–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auger, R.R. Sleep-related eating disorders. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2006, 3, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Arnulf, I.; Gross, E.; Dodet, P. Kleine-Levin syndrome: A neuropsychiatric disorder. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2018, 174, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.P.; Fong, S.Y.Y.; Ho, C.K.W.; Yu, M.W.M.; Wing, Y.K. Parasomnia among psychiatric outpatients: A clinical, epidemiologic, cross-sectional study. J Clin Psychiatry 2008, 69, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.J. Parasomnias: An updated review. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 753–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulda, S.; Hornyak, M.; Müller, K.; Cerny, L.; Beitinger, P.A.; Wetter, T.C. Development and validation of the Munich Parasomnia Screening (MUPS). Somnologie 2008, 12, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komada, Y.; Breugelmans, R.; Fulda, S.; Nakano, S.; Watanabe, A.; Noda, C.; et al. Japanese version of the Munich Parasomnia Screening: Translation and linguistic validation of a screening instrument for parasomnias and nocturnal behaviors. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015, 11, 2953–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.C.; Lundgren, J.D.; O’Reardon, J.P.; Martino, N.S.; Sarwer, D.B.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): Psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the Night Eating Syndrome. Eat Behav 2008, 9, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnulf, I.; Zhang, B.; Uguccioni, G.; Flamand, M.; de Fontréaux, A.N.; Leu-Semenescu, S.; Brion, A. A scale for assessing the severity of arousal disorders. Sleep 2014, 37, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.H.; Mahowald, W. Review of nocturnal sleep-related eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1994, 15, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoar, S.; Naderan, M.; Mahmoodzadeh, H.; Shoar, N.; Lotfi, D. Night eating syndrome: A psychiatric disease, a sleep disorder, a delayed circadian rhythm, and/or a metabolic condition? Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 2019, 14, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenck, C.H.; Mahowald, M.W. Dopaminergic and opiate therapy of nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder associated with sleepwalking or unassociated with another nocturnal disorder. Sleep 2002, 25, A249–A250. [Google Scholar]

- Grunvald, E.; DeConde, J. Phentermine-topiramate extended release for the dual treatment of obesity and sleep-related eating disorder: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2022, 16, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkelman, J.W.; Wipper, B.; Purks, J.; Mei, L.; Schoerning, L. Topiramate reduces nocturnal eating in sleep-related eating disorder. Sleep 2020, 43, zsaa060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenck, C.; Mahowald, M. Topiramate therapy of sleep related eating disorder (SRED). Sleep 2006, 29, A268. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, J.W. Treatment of nocturnal eating syndrome and sleep-related eating disorder with topiramate. Sleep Med 2003, 4, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazi, S.E.; Mohammed, J.M.M.; Schenck, C.H. Sleepwalking, sleep-related eating disorder and sleep-related smoking successfully treated with topiramate: A case report. Sleep Sci 2022, 15, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkelman, J.W. Efficacy and tolerability of open-label topiramate in the treatment of sleep-related eating disorder: A retrospective case series. J Clin Psychiatry 2006, 67, 1729–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Salio, A.; Soler-Algarra, S.; Calvo-Garcia, I.; Sanchez-Martin, M. Nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder that responds to topiramate. Rev Neurol 2007, 45, 276–279. [Google Scholar]

- Miyaoka, T.; Yasukawa, R.; Tsubouchi, K.; Miura, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Sukegawa, T.; et al. Successful treatment of nocturnal eating/drinking syndrome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2003, 18, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapp, A.A.; Fischer, E.C.; Deutschle, M. The effect of agomelatine and melatonin on sleep-related eating: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2017, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.H.; Mahowald, M.W. Combined bupropion-levodopa-trazodone therapy of sleep-related eating and sleep disruption in two adults with chemical dependency. Sleep 2000, 23, 587–588. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, K.; Kimura, A.; Nagao, K.; Yoshiike, T.; Kuriyama, K. Treatment of sleep-related eating disorder with suvorexant: A case report on the potential benefits of replacing benzodiazepines with orexin receptor antagonists. PCN Reports 2023, 2, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Kuriyama, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inada, K.; Nishimura, K.; Inoue, Y. The efficacy of add-on ramelteon and subsequent dose reduction in benzodiazepine derivatives/Z-drugs for the treatment of sleep-related eating disorder and night eating syndrome: A retrospective analysis of consecutive patients. J Clin Sleep Med 2021, 17, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauri, P.J.; Silber, M.H.; Boeve, B.F. The treatment of parasomnias with hypnosis: A 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Sleep Med 2007, 3, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, G. Hypnotherapy and parasomnias. In The Parasomnias and Other Sleep-Related Movement Disorders; Thorpy, M.J., Plazzi, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, D.; Nesbitt, A.; Biabani, N.; Drakatos, P.; Selsick, H.; Leschziner, G.D.; et al. A novel group cognitive behavioral therapy approach to adult non-rapid eye movement parasomnias. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 679272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbiati, A.; Rinaldi, F.; Giora, E.; Ferini-Strambi, L.; Marelli, S. Behavioural and cognitive-behavioral treatments for parasomnias. Behav Neurol 2015, 2015, 786928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, J.M.; Monti, D. Sleep disturbance in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Sleep Med Rev 2000, 4, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliu, O.; Vasile, D.; Mangalagiu, A.G.; Petrescu, M.B.; Candea, C.A.; Tudor, C.; et al. Current treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder- A review of therapeutic guidelines and good practice recommendations. RJMM 2020, CXXIII, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staner, L. Sleep and anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2003, 5, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Nakayama, J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol Int 2017, 66, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Török, N.; Vécsei, L. Are 5-HT1 receptor agonists effective anti-migraine drugs? Expert Opin Pharmacother 2021, 22, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sîrbu, C.A.; Manole, A.M.; Vasile, M.; Toma, G.S.; Dobrican, L.R.; Vîrvara, D.G.; Vasiliu, O. Cannabinoids- a new therapeutic strategy in neurology. RJMM 2022, 3, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.A.; Walsh, B.T. Eating disorders: Clinical features and pathophysiology. Physiol Behav 2004, 81, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranzo, A. Parasomnias and sleep-related movement disorders in older adults. Sleep Med Clin 2022, 17, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Operational criteria | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | All age groups were allowed. The main diagnosis explored was “sleep-related eating disorder”. Diagnoses made according to the DSM, ICSD, or ICSD nosographic systems (no limitations regarding the edition) were permitted, but also original criteria constructed by authors of the respective reports. |

Unspecified diagnoses or reports that included various EDs or sleep disorders without clarifying what criteria were used during the research. |

| Intervention | Any type of study, such as clinical or preclinical research, epidemiological or clinical, prospective or retrospective, etc. Any type of review, such as systematic, narrative, scoping, meta-analysis, umbrella review, etc. |

Studies with undetermined methodology and reviews with unspecified design. |

| Environment | Inpatient, outpatient, daycare, and general population. | Unspecified environment. |

| Primary and secondary variables | Prevalence, incidence, risk factors, clinical diagnosis, pathophysiological data, psychological evaluation, and treatment | Imprecisely defined or poorly characterized variables, and reports without pre-defined outcomes. |

| Study design | Primary and secondary reports, clinical and preclinical research. | Unspecified or insufficiently defined designs. |

| Language | Any language of publication was admitted. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).