Submitted:

18 October 2023

Posted:

19 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

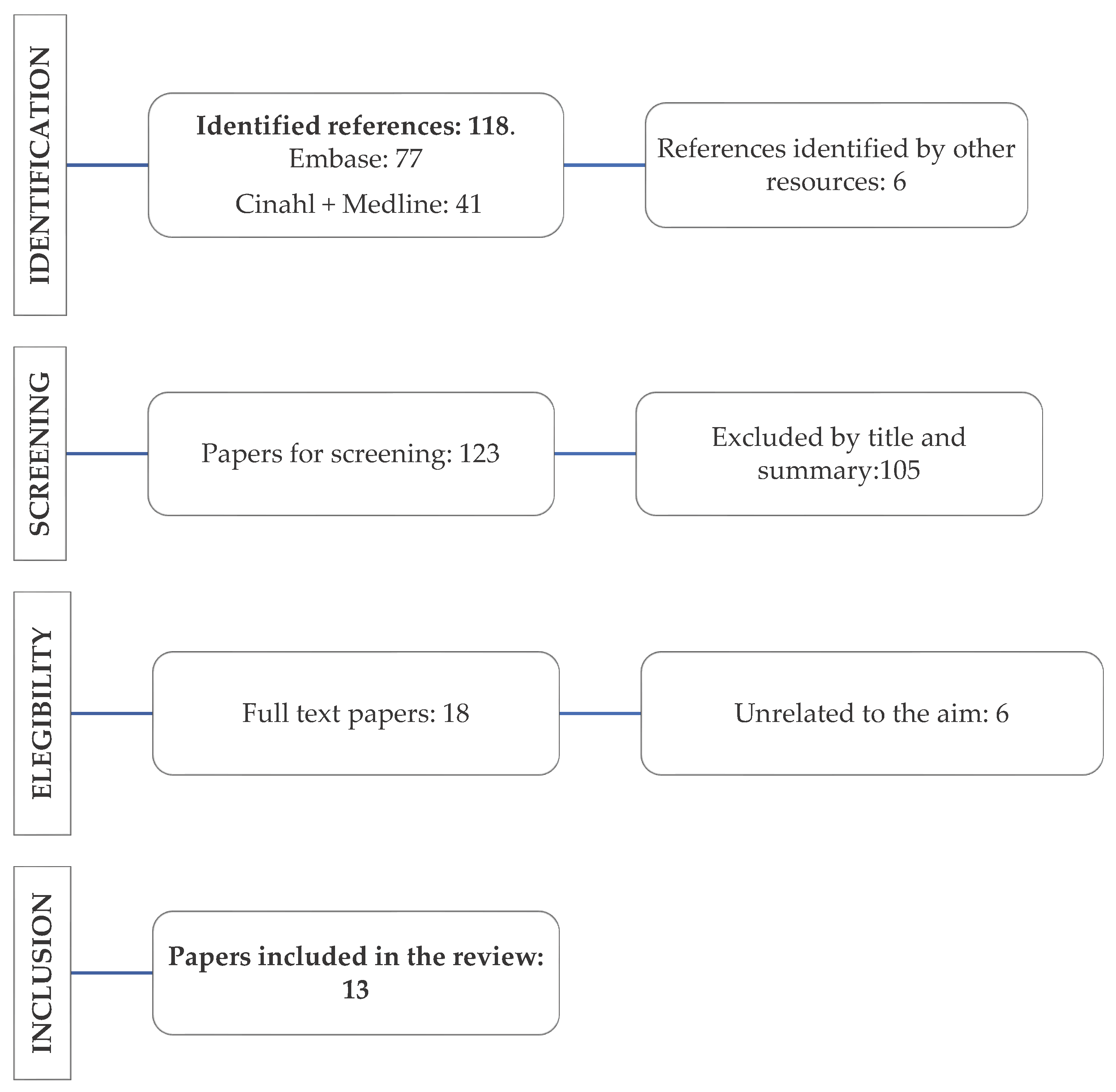

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

- Stage 1: Identification of the research question.

- Stage 2: Identification of pertinent or relevant studies.

- Stage 3: Studies selection according to inclusion criteria.

- Stage 4: Data registration and report.

- Stage 5: Collection, summary, and communication of results.

2.2. Study Selection Criteria

- Quantitative data on the impact of delayed discharge on health outcomes (e.g., care quality, satisfaction, number of infections, mental health, mortality, morbidity, readmissions, and functionality)

- Qualitative data on delayed discharge experiences from the perspective of patients (e.g., perceived impact on health or patient’s experience), health professionals and hospitals

- Information on delayed discharge costs due to unnecessary hospitalisation days

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bai, A. D.; Dai, C.; Srivastava, S.; Smith, C. A.; Gill, S. S. Risk factors, costs and complications of delayed hospital discharge from internal medicine wards at a Canadian academic medical centre: retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019, 19, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-García, A.; Turner, S.; Pizzo, E.; Hudson, E.; Thomas, J.; Raine, R. Impact and experiences of delayed discharge: A mixed-studies systematic review. Health Expectations 2018, 21, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnable, A.; Welsh, D.; Lundrigan, E.; Davis, C. Analysis of the Influencing Factors Associated With Being Designated Alternate Level of Care. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2015, 27, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Lead, P. A. L. C. Caring for our aging population and addressing alternate level of care; Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Toronto, 2011.

- Jasinarachchi, K. H.; Ibrahim, I. R.; Keegan, B. C.; Mathialagan, R.; McGourty, J. C.; Phillips, J. R.; Myint, P. K. Delayed transfer of care from NHS secondary care to primary care in England: its determinants, effect on hospital bed days, prevalence of acute medical conditions and deaths during delay, in older adults aged 65 years and over. BMC Geriatr 2009, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micallef, A.; Buttigieg, S. C.; Tomaselli, G.; Garg, L. Defining Delayed Discharges of Inpatients and Their Impact in Acute Hospital Care: A Scoping Review. Int J Health Policy Manag 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE Proyecciones de Población 2020-2070; 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/pp_2020_2070.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Gallardo Peralta, L. P.; Sánchez Moreno, E.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, V.; García Martín, M. La investigación sobre soledad y redes de apoyo social en las personas mayores: una revisión sistemática en Europa. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2023, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Boletin Oficial del Estado Ley 39/2006, de 14 de diciembre, de Promoción de la Autonomía Personal y Atención a las personas en situación de dependencia; 2006; Vol. 299, p. 15. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2006-21990 (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Mendoza Giraldo, D.; Navarro, A.; Sánchez-Quijano, A.; Villegas, A.; Asencio, R.; Lissen, E. Impact of delayed discharge for nonmedical reasons in a tertiary hospital internal medicine department. Rev Clin Esp 2012, 212, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellico-López, A.; Cantarero, D.; Fernández-Feito, A.; Parás-Bravo, P.; De Las Cuevas, J. C.; Paz-Zulueta, M. Factors associated with bed-blocking at a university hospital (Cantabria, Spain) between 2007 and 2015: A retrospective observational study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J.; Moher, D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and extensions: A scoping review. Syst Rev 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C. M.; Mcinerney, P.; Soares, C. B. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews Chronic Diseases Management View project Tonsillectomy View project; 2015.

- Rodríguez-Vera, F. J.; Marín Fernández, Y.; Sánchez, A.; Borrachero, C.; Pujol de la Llave, E. Adecuación de los ingresos y estancias en un Servicio de Medicina Interna de un hospital de segundo nivel utilizando la versión concurrente del AEP (Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol). Anales de Medicina Interna 2003, 20, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellico-López, A.; Fernández-Feito, A.; Cantarero, D.; Herrero-Montes, M.; Cuevas, J. C. D. Las; Parás-Bravo, P.; Paz-Zulueta, M. Delayed discharge for non-clinical reasons in hip procedures: Differential characteristics and opportunity cost. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellico-López, A.; Fernández-Feito, A.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Herrero-Montes, M.; Cayón-De las Cuevas, J.; Cantarero, D.; Paz-Zulueta, M. Differential characteristics of cases of patients diagnosed with pneumonia and delayed discharge for non-clinical reasons in Northern Spain. Int J Clin Pract 2021, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellico-López, A.; Fernández-Feito, A.; Cantarero, D.; Herrero-Montes, M.; Cayón-de las Cuevas, J.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Paz-Zulueta, M. Cost of stay and characteristics of patients with stroke and delayed discharge for non-clinical reasons. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellico-López, A.; Herrero-Montes, M.; Cantarero Prieto, D.; Fernández-Feito, A.; Cayon-De las Cuevas, J.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Paz-Zulueta, M. Patient deaths during the period of prolonged stay in cases of delayed discharge for nonclinical reasons at a university hospital: a cross sectional study. PeerJ 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellico López, A.; Paz-Zulueta, M.; Fernández-Feito, A.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Santibañez, M.; Cantarero Prieto, D. Cases of bed blockage in Northern Spain during 2010–2014: Delayed discharge from acute hospitalization to long-term care. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2018, 66, S403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Aledo, V.; Carrillo-Alcaraz, A.; Campillo-Soto, Á.; Flores-Pastor, B.; Leal-Llopis, J.; Fernández-Martín, M. P.; Carrasco-Prats, M.; Aguayo-Albasini, J. L. Associated factors and cost of inappropriate hospital admissions and stays in a second-level hospital. American Journal of Medical Quality 2009, 24, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrana García, J. L.; Delgado Fernández, M.; Cruz Caparrós, G.; Escalante, M. D. M.; Díez García, F.; Ruiz Bailén, M. Predictive factors for inappropriate hospital stays in an internal medicine department. Med Clin (Barc) 2001, 117, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Aledo, V.; Carrillo-Alcaraz, A.; Flores-Pastor, B.; Moreno-Egea, A.; Carrasco-Prats, M.; Aguayo-Albasini, J. L. Reduction in inappropriate hospital use based on analysis of the causes, 2012.

- Monteis Catot, J.; Martín-Baranera, M.; Soler, N.; Vilaró, J.; Moya, C.; Francesc Martínez, N.; Riu, M.; Puig, C.; Riba, A.; Navarro, G.; et al. Impacto de una intervención de autoevaluación clínica sobre la adecuación de la estancia hospitalaria, 2007; Vol. 21.

| Database | Search Strategy | Search Date | Results | Selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embase | ((’delayed discharges’ or ’discharge delays’ or ’bed blocking’ or ’timely discharge’ or ’unnecessary days’ or ’inappropriate stays’) and (’spain’ or ’spanish’)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, full text, caption text] |

28/03/2023 | 77 | 3 |

| CINAHL+ Medline | AB (delayed discharge or delayed discharge from hospital or bed-blocking or delayed transfer of care) AND TX (spain or spanish or españa) |

28/03/2023 | 41 | 10 |

| Author and Year | Study Type | Aim | Participants and Context | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pellico-López, Fernández-Feito et al., (2022) [18] | Descriptive, observational, cross-sectional, and retrospective study | Describing the costs and characteristics of patients diagnosed with stroke and discharged late for non-clinical reasons, and evaluating the connection between total stay duration and patient’s characteristics and care context | 443 patients diagnosed with stroke and discharged late for non-clinical reasons in the University Hospital “Marqués de Valdecilla” (HUMV, by its Spanish acronym) (2007-2015) | Delayed discharges increase the total duration of stay by approximately a week. These patients with stroke have longer hospital stays, more complex care, and higher costs than other cases of delayed discharges. |

| Pellico-López, Herrero-Montes, (2022) [19] | Descriptive, observational, cross-sectional, and retrospective study | Describing the characteristics of patients deceased during delayed stays in terms of duration of hospital stay, patient’s characteristics, and care context | 198 patients deceased during their hospital stay after being discharged from the HUMV (2007-2015) | 6.57% of patients with delayed discharges for non-clinical reasons died during their hospital stay. The most common diagnosis among the deceased was simple pneumonia, likely caused by factors such as old age, comorbidity, fragility, or complications arising from hospital infections. |

| Pellico-López, Fernández-Feito, Cantarero et al., (2021)[16] | Descriptive, observational, cross-sectional, and retrospective study | Quantifying the connexion between stay and its costs in hip processes with delayed discharge for non-clinical reasons | 306 patients admitted to the HUMV (2007-2015) for hip processes with delayed discharges for non-clinical reasons | Average delayed stay was 7.12 days. The cost of delayed stay amounted to €641,002.09. Up to 85.29% of patients lived in urban areas near the hospital and 3.33% had been transferred to a long-stay centre for recovery. The percentage of patients with hip procedures and delayed discharge was lower to prior reports; however, their duration of stay was longer. |

| Pellico -López, Fernández-Feito et al., (2021)[17] | Descriptive, observational, cross-sectional, and retrospective study | Understanding which characteristics are common in pneumonia patients, compared to other cases of delayed discharge. | 170 patients diagnosed with pneumonia who were discharged late in the HUMV (2007-2015) | Pneumonia patients were older, less complex, and had higher death rates than the rest of the patients. |

| Pellico -López et al., (2019) [11] | Descriptive, observational, cross-sectional, and retrospective study | Quantifying the number of delayed discharge cases and inappropriate hospitalisation days and identifying the use of health services linked to bed-blocking | 3015 patients with delayed discharges in the HUMV (2007-2015) | The characteristics most frequently associated with longer stays were the following: increased complexity, diagnosis implying lack of functional capacity, surgical treatment, having to wait for a destination when discharged or getting back home. Multiple-component interventions linked to discharge planning may favour inefficiency reduction minimising unnecessary stays. |

| Pellico-López et al., (2018) [20] | Descriptive, retrospective study | Identifying which characteristics may influence the issue and quantifying inappropriate hospitalisation days. | This study included three public hospitals of a northern Spanish region (Cantabria), during 2010–2014. | In the period from 2010 to 2014, 1415 bed-blocking cases were found in Cantabria hospitals waiting to be admitted to long-stay hospitals. |

| Rojas-García et al., (2018) [2] | Systematic review | Systematically reviewing delayed discharge experiences from the perspective of patients, health professionals and hospitals, and their impact on patients’ outcomes and costs. | 37 papers were included of which 2 were developed in Spain | Most of the research was conducted poorly which asks for precaution when considering its practical implications. The results suggest that the adverse effects of delayed discharges are both direct, due to the potential health problems they may cause to patients, and indirect owing to increased pressure on healthcare workers. |

| Soria-Aledo et al., (2012) [23] | Descriptive, pre- and post-intervention, retrospective study | Reducing inappropriate admission and stays, as well as analysing the hospital costs saved by inadequate stay reduction. | 1350 stays at J. M. Morales Meseguer Hospital | Inappropriate stays considerably decreased from 24.6% to 10.4%. Inadequacy cost in the study sample dropped from 147,044 euros to 66,642 euros. |

| Mendoza Giraldo et al., (2012) [10] | Unicentric, observational, open, and prospective study | Analysing discharge delays for non-medical reasons at the IM Unit of a third level hospital and establishing the clinical and socio-familial factors linked to this situation. | 164 patients admitted to the IM unit of the Virgen del Rocío University Hospital (HUVR, by its Spanish acronym) whose discharges were delayed for non-medical reasons (between 1 February 2008 and 31 January 2009). | 3.5% of discharges were delayed for non-medical reasons. Patients whose discharges were delayed were older and presented higher prevalence of acute cerebrovascular disease and problems related to alcohol or benzodiazepine consumption.The main reasons given for not being discharged were family overload and/or inability to provide care, and lack of family or social support network. |

| Soria-Aledo et al., (2009) [21] | Retrospective, descriptive study | Analysing variables linked to inappropriate admissions and hospital stays, and their economic repercussions. | A total of 725 medical records and 1355 stays at J. M. Morales Meseguer Hospital were selected. | The study found 7.4% of admissions and 24.6% of stays to be inappropriate. Most common causes of inappropriate stays were diagnosis or therapeutical procedures that can be performed on an outpatient basis, waiting for test results or consultations, physician conservative attitude, bank holidays, and lack of a diagnostic or treatment plan |

| Monteis-Catot et al., (2007)[24] | Pre- and post-intervention study using«adeQhos®» questionnaire | Evaluating the impact of an intervention on the percentage of inappropriate stays (IS) to verify the hypothesis that a simple information and participation intervention (adeQhos®) allows to reduce IS percentage. | Design consisting of 2 intervention groups and their corresponding control groups in acute hospitals in Catalonia (708 patients per group) | No significant reduction of hospital inadequacy was observed after a low intensity intervention. |

| Rodríguez-Vera, (2003) [15] | Observational, descriptive study | Determining admissions and stays inadequacy at an IM unit using AEP (Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol) concurrent version. | 59 patients admitted to Juan Ramón Jiménez Hospital | 33% of stays was found to be inadequate. Waiting for complementary test results and interconsultations was the most common reason for inadequate stay. |

| Zambrana-García et al., (2001) [22] | Observational, descriptive, and prospective study | Knowing the factors that may influence inadequate stays in an IM unit. | 1,046 of the 13,384 stays generated during 1998 in the IM unit of the Poniente Hospital. | A total of 176 stays were considered inadequate (16.8%). A logistic regression analysis revealed the main factors of stay inadequacy to be days of stay, day of the week, and diagnosis on admission. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).