Submitted:

18 October 2023

Posted:

19 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

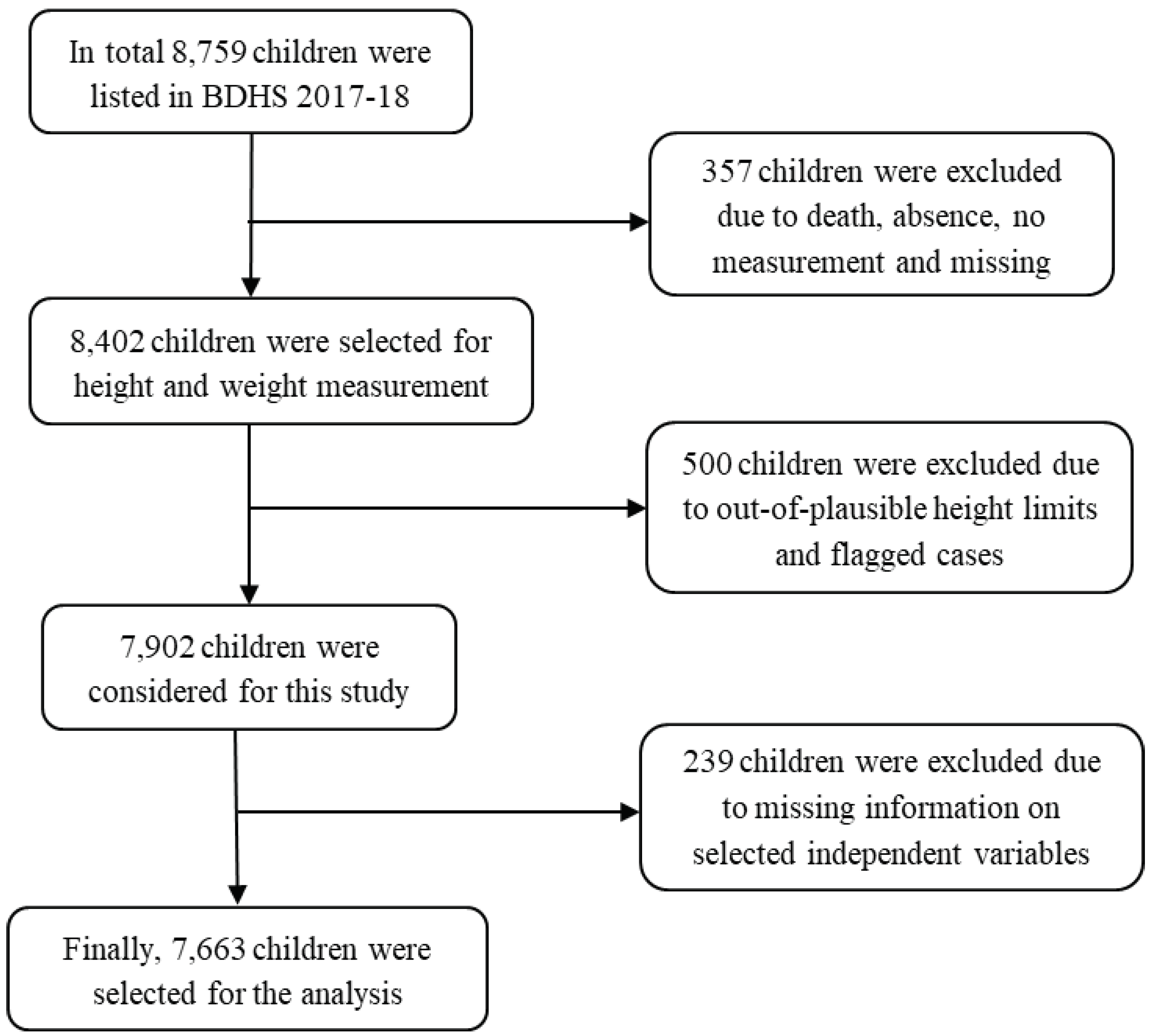

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Outcome Variables

2.3. Independent Variables and Operational Definition

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Background Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence of Diarrhea, Fever, and Coexistence of Diarrhea and Fever

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahumud, R.A.; Alam, K.; Renzaho, A.M.; Sarker, A.R.; Sultana, M.; Sheikh, N.; Rawal, L.B.; Gow, J. Changes in inequality of childhood morbidity in Bangladesh 1993-2014: A decomposition analysis. Plos one 2019, 14, e0218515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Diarrhoeal disease. World Health Organization (WHO) 2017.

- MacGill, M. What you should know about diarrhea. [cited at March 22, 2021]. Available from: https:// www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/158634.php 2020.

- UNICEF. Under-five mortality. United Nations Children's Fund 2023.

- Antillón, M.; Warren, J.L.; Crawford, F.W.; Weinberger, D.M.; Kürüm, E.; Pak, G.D.; Marks, F.; Pitzer, V.E. The burden of typhoid fever in low-and middle-income countries: a meta-regression approach. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2017, 11, e0005376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoina, D. Fever, fever patterns and diseases called ‘fever’–a review. Journal of infection and public health 2011, 4, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIPORT. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), and ICF. Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA. 2020.

- Pinzón-Rondón, Á.M.; Zárate-Ardila, C.; Hoyos-Martínez, A.; Ruiz-Sternberg, Á.M.; Vélez-van-Meerbeke, A. Country characteristics and acute diarrhea in children from developing nations: a multilevel study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Hossain, M.M. Prevalence and determinants of fever, ARI and diarrhea among children aged 6–59 months in Bangladesh. BMC pediatrics 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoHFW. Success Factors for Women’s and Children’s Health: Bangladesh. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Bangladesh, Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health, WHO, World Bank and Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. 2015.

- WB. Mortality rate, under-5 (per 1,000 live births) - Bangladesh. World Bank 2021.

- BBS. Report on sample vital registration system-2015. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics [BBS]. Dhaka: Statistics Division, Ministry of Planning 2016.

- Thiam, S.; Diène, A.N.; Fuhrimann, S.; Winkler, M.S.; Sy, I.; Ndione, J.A.; Schindler, C.; Vounatsou, P.; Utzinger, J.; Faye, O. Prevalence of diarrhoea and risk factors among children under five years old in Mbour, Senegal: a cross-sectional study. Infectious diseases of poverty 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldu, W.; Bitew, B.D.; Gizaw, Z. Socioeconomic factors associated with diarrheal diseases among under-five children of the nomadic population in northeast Ethiopia. Tropical medicine and health 2016, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amugsi, D.A.; Aborigo, R.A.; Oduro, A.R.; Asoala, V.; Awine, T.; Amenga-Etego, L. Socio-demographic and environmental determinants of infectious disease morbidity in children under 5 years in Ghana. Global health action 2015, 8, 29349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, E.T.; Gari, S.R.; Kloos, H.; Mengistie, B. Diarrheal morbidity and predisposing factors among children under 5 years of age in rural East Ethiopia. Tropical Medicine and Health 2020, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, M.M.; Hasan, M.M.; Davey, R. Determinants of childhood morbidity in Bangladesh: evidence from the demographic and health survey 2011. BMJ open 2015, 5, e007538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaudecker, E.P.; Steinhoff, M.C.; Moore, S.R. Interactions of diarrhea, pneumonia, and malnutrition in childhood: recent evidence from developing countries. Current opinion in infectious diseases 2011, 24, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banga, D.; Baren, M.; Ssonko, N.V.; Sikakulya, F.K.; Tibamwenda, Y.; Banga, C.; Ssebuufu, R. Comorbidities and factors associated with mortality among children under five years admitted with severe acute malnutrition in the nutritional unit of Jinja Regional Referral Hospital, Eastern Uganda. International journal of pediatrics 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. More women and children survive today than ever before – UN report. World Health Organization (WHO) 2019.

- Adedokun, S.T.; Yaya, S. Childhood morbidity and its determinants: evidence from 31 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Global Health 2020, 5, e003109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, P. Socio-demographic and environmental factors associated with diarrhoeal disease among children under five in India. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bursac, Z.; Gauss, C.H.; Williams, D.K.; Hosmer, D.W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source code for biology and medicine 2008, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiese, M.S.; Ronna, B.; Ott, U. P value interpretations and considerations. Journal of thoracic disease 2016, 8, E928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. How to choose the level of significance: A pedagogical note. 2015.

- DHS. Children with fever and diarrhoea. The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program STATcompiler ICF. Funded by USAID. [cited at November 29, 2021] Available from: http://www.statcompiler.com 2015.

- Hasan, M.M.; Richardson, A. How sustainable household environment and knowledge of healthy practices relate to childhood morbidity in South Asia: analysis of survey data from Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan. BMJ open 2017, 7, e015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashmi, R.; Paul, R. Determinants of multimorbidity of infectious diseases among under-five children in Bangladesh: role of community context. BMC pediatrics 2022, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zayed, S.R.; Talukdar, F.; Jahan, F.; Asaduzzaman, T.; Shams, F. Beyond Gender Parity: Actualization of Benefits Verses Fallacy of Promises, A Case Study of Bangladesh; World Bank: 2018.

- Zaidman, E.A.; Scott, K.M.; Hahn, D.; Bennett, P.; Caldwell, P.H. Impact of parental health literacy on the health outcomes of children with chronic disease globally: A systematic review. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 2023, 59, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houweling, T.A.; Kunst, A.E.; Looman, C.W.; Mackenbach, J.P. Determinants of under-5 mortality among the poor and the rich: a cross-national analysis of 43 developing countries. International journal of epidemiology 2005, 34, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.R.K.; Rahman, M.S.; Khan, M.M.H. Levels and determinants of complementary feeding based on meal frequency among children of 6 to 23 months in Bangladesh. BMC public health 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- URMC. Viruses, Bacteria, and Parasites in the Digestive Tract. . Health Encyclopedia, University of Rochester Medical Center 2023.

- Signs, R.J.; Darcey, V.L.; Carney, T.A.; Evans, A.A.; Quinlan, J.J. Retail food safety risks for populations of different races, ethnicities, and income levels. Journal of food protection 2011, 74, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, K.; Leon, J.; Rebolledo, P.; Scallan, E. The impact of socioeconomic status on foodborne illness in high-income countries: a systematic review. Epidemiology & Infection 2015, 143, 2473–2485. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, R.; Khan, H.T.; Ball, E.; Caldwell, K. Climate change impact: the experience of the coastal areas of Bangladesh affected by cyclones Sidr and Aila. Journal of environmental and public health 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, G.; Chase, C. Water supply, sanitation, and hygiene. Injury Prevention and Environmental Health. 3rd edition 2017.

- John, J.; Bavdekar, A.; Rongsen-Chandola, T.; Dutta, S.; Kang, G. Estimating the incidence of enteric fever in children in India: a multi-site, active fever surveillance of pediatric cohorts. BMC public health 2018, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.D. How Our Careers Affect Our Children. Harvard Business Review 2018.

- Cerrato, J.; Cifre, E. Gender inequality in household chores and work-family conflict. Frontiers in psychology 2018, 9, 384557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Children, S.t. Gender Roles Can Create Lifelong Cycle of Inequality. Save the Children 2019.

- Walson, J.L.; Berkley, J.A. The impact of malnutrition on childhood infections. Current opinion in infectious diseases 2018, 31, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkegren, E.; Svaleryd, H. Birth order and child health; Working paper: 2017.

- Price, J. Parent-child quality time: Does birth order matter? Journal of human resources 2008, 43, 240–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.M.; Salehin, M.A. Climate Change in Bangladesh: Effect versus Awareness of the Local People and Agencies of Rajshahi City. Social Science Journal 2019, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Global, C. Urban development must be planned and climate-resilient – Experience from Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. Climate and Development Knowledge Network 2020.

- Alam, M.Z.; Rahman, M.A.; Al Firoz, M.A. Water supply and sanitation facilities in urban slums: a case study of Rajshahi City corporation slums. American Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 2013, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number | (%) | No of response/ missing or excluded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 7,663 | 100.0 | 8,759/1,096 |

| Dependent variables | |||

| Diarrhea | 8,759/361 | ||

| Fever | 8,759/361 | ||

| Independent variables | |||

| Age of the mothers (in years) | |||

| 15-19 | 938 | 12.2 | 8,759/0 |

| 20-24 | 2,679 | 35.0 | |

| 25-29 | 2,146 | 28.0 | |

| 30-34 | 1,295 | 16.9 | |

| 34-39 | 481 | 6.3 | |

| ≥ 40 | 124 | 1.6 | |

| Parents’ education | |||

| Both parents uneducated | 295 | 3.8 | 8,759/153 |

| Only father uneducated | 865 | 11.3 | |

| Only mother uneducated | 243 | 3.2 | |

| Both parents educated | 6,260 | 81.7 | |

| Mother currently working | |||

| No | 4,561 | 59.5 | 8,759/0 |

| Yes | 3,102 | 40.5 | |

| Underweight mother | |||

| No | 6,537 | 85.3 | 8,759/0 |

| Yes | 1,126 | 14.7 | |

| Mothers received antenatal care # | |||

| No | 364 | 8.0 | 8,759/3,747 |

| Yes | 4,175 | 92.0 | |

| Mothers received postnatal care # | |||

| No | 1,509 | 33.3 | 8,759/ 3,753 |

| Yes | 3,025 | 66.7 | |

| Mother's attitude towards wife beating | 8,759/0 | ||

| Not justified | 6,266 | 81.8 | |

| Justified | 1,397 | 18.2 | |

| Mother’s decision-making autonomy | |||

| No | 6,581 | 85.9 | 8,759/154 |

| Yes | 1,082 | 14.1 | |

| Age of the children | |||

| 0-11 months | 1,677 | 21.9 | 8,759/447 |

| 12-23 months | 1,577 | 20.6 | |

| 24-35 months | 1,481 | 19.3 | |

| 36-47 months | 1,414 | 18.4 | |

| 48-59 months | 1,514 | 19.8 | |

| Sex of the children | |||

| Male | 3,996 | 52.2 | 8,759/0 |

| Female | 3,667 | 47.8 | |

| Underweight children | |||

| No | 5,972 | 77.9 | 8,759/709 |

| Yes | 1,691 | 22.1 | |

| Birth orderof the children | |||

| First | 2,903 | 37.9 | 8,759/0 |

| Second | 2,507 | 32.7 | |

| Third | 1,298 | 16.9 | |

| Fourth and above | 955 | 12.5 | |

| Small birth weight # | |||

| No | 1,816 | 38.3 | 8,759/3,455 |

| Yes | 325 | 6.9 | |

| Not weighted | 2,594 | 54.8 | |

| Mass media exposure | |||

| No | 2,774 | 36.2 | 8,759/0 |

| Yes | 4,889 | 63.8 | |

| Source of drinking water | |||

| Improved | 6,659 | 86.9 | 8,759/0 |

| Unimproved | 1,004 | 13.1 | |

| Type of toilet facility | |||

| Improved | 4,362 | 56.9 | 8,759/0 |

| Unimproved | 3,301 | 43.1 | |

| Solid waste use in cooking | |||

| No | 2,219 | 29.0 | 8,759/6 |

| Yes | 5,444 | 71.0 | |

| Wealth index | |||

| Poorest | 1,707 | 22.3 | 8,759/0 |

| Poorer | 1,545 | 20.2 | |

| Middle | 1,382 | 18.0 | |

| Richer | 1,535 | 20.0 | |

| Richest | 1,494 | 19.5 | |

| Place of residence | |||

| Urban | 2,605 | 34.0 | 8,759/0 |

| Rural | 5,058 | 66.0 | |

| Division | |||

| Barisal | 800 | 10.4 | 8,759/0 |

| Chattogram | 1,246 | 16.2 | |

| Dhaka | 1,079 | 14.1 | |

| Khulna | 810 | 10.6 | |

| Mymensingh | 911 | 11.9 | |

| Rajshahi | 796 | 10.4 | |

| Rangpur | 879 | 11.5 | |

| Sylhet | 1,142 | 14.9 |

| Variables | Diarrhea | Fever | Comorbidity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Prevalence (95% CI) | n | Prevalence (95% CI) |

n | Prevalence (95% CI) | |

| Total | 386 | 4.9 (4.3-5.5) | 2561 | 33.7 (32.3-35.2) | 218 | 2.7 (2.3-3.2) |

| Age of the mothers (in years) | ||||||

| 15-19 | 61 | 6.4 (4.9-8.3) | 352 | 37.1 (33.5-40.9) | 39 | 3.9 (2.8-5.5) |

| 20-24 | 141 | 5.2 (4.3-6.2) | 857 | 32.5 (30.4-34.7) | 69 | 2.6 (2.0-3.3) |

| 25-29 | 120 | 5.3 (4.3-6.4) | 732 | 33.8 (31.4-36.3) | 66 | 2.8 (2.1-3.6) |

| 30-34 | 46 | 3.3 (2.4-4.6) | 428 | 33.7 (30.8-36.7) | 32 | 2.5 (1.6-3.7) |

| 34-39 | 12 | 2.7 (1.5-4.8) | 153 | 33.7 (29.0-38.6) | 6 | 1.3 (0.5-3.0) |

| ≥ 40 | 6 | 3.8 (1.5-8.9) | 39 | 30.4 (22.2-40.1) | 6 | 3.8 (1.5-8.9) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.008 | p = 0.301 | p = 0.114 | |||

| Parents’ education | ||||||

| Both parents uneducated | 10 | 4.8 (2.5-8.9) | 105 | 34.4 (28.5-40.7) | 6 | 2.8 (1.2-6.2) |

| Only father uneducated | 34 | 3.5 (2.4-4.9) | 276 | 32.4 (28.9-36.0) | 16 | 1.5 (0.9-2.6) |

| Only mother uneducated | 20 | 8.7 (5.5-13.4) | 73 | 29.3 (23.5-35.8) | 10 | 3.7 (1.9,7.2) |

| Both parents educated | 322 | 4.9 (4.3-5.6) | 2107 | 34.0 (32.4-35.7) | 186 | 2.9 (2.4-3.4) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.032 | p = 0.467 | p = 0.172 | |||

| Mother currently working | ||||||

| No | 242 | 5.1 (4.5-5.9) | 1552 | 34.4 (32.6-36.2) | 139 | 3.0 (2.5-3.5) |

| Yes | 144 | 4.5 (3.7-5.4) | 1009 | 32.7 (30.7-34.8) | 79 | 2.4 (1.9-3.1) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.246 | p = 0.214 | p = 0.175 | |||

| Underweight mother | ||||||

| No | 67 | 6.0 (4.6-7.8) | 2163 | 33.5 (32.0-35.1) | 174 | 2.6 (2.2-3.0) |

| Yes | 319 | 4.7 (4.2-5.3) | 398 | 34.7 (31.4-38.2) | 44 | 3.8 (2.8-5.2) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.070 | p = 0.508 | p = 0.021 | |||

| Mothers received antenatal care | ||||||

| No | 27 | 7.5 (4.9-11.3) | 138 | 39.0 (32.8-45.4) | 13 | 3.3 (1.8-5.8) |

| Yes | 285 | 6.6 (5.8-7.5) | 1533 | 36.8 (35.0-38.7) | 163 | 3.8 (3.2-4.5) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.216 | p = 0.518 | p = 0.623 | |||

| Mothers received postnatal care | ||||||

| No | 100 | 6.8 (5.6-8.4) | 530 | 34.7 (32.1-37.5) | 55 | 3.7 (2.8-4.8) |

| Yes | 212 | 6.6 (5.7-7.7) | 1140 | 38.2 (36.0-40.4) | 121 | 3.8 (3.1-4.7) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.819 | p = 0.040 | p = 0.822 | |||

| Mothers attitude towards wife beating | ||||||

| No | 332 | 5.2 (4.6-5.9) | 2019 | 32.5 (31.0-34.1) | 187 | 2.9 (2.5-3.5) |

| Yes | 54 | 3.4 (2.5-4.6) | 542 | 38.7 (35.8-41.7) | 31 | 1.9 (1.3-2.8) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.012 | p = 0.0001 | p = 0.042 | |||

| Mother’s decision-making autonomy | ||||||

| No | 51 | 4.6 (3.4-6.2) | 379 | 34.7 (31.3-38.4) | 192 | 2.8 (2.3-3.2) |

| Yes | 335 | 4.9 (4.3-5.6) | 2182 | 33.5 (32.0-35.1) | 26 | 2.5 (1.7-3.8) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.699 | p = 0.521 | p = 0.699 | |||

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.091 | p = 0.009 | p = 0.255 | |||

| Age of the children | ||||||

| 0-11 months | 101 | 5.7 (4.5-7.2) | 608 | 36.8 (34.3-39.5) | 63 | 3.5 (2.6-4.7) |

| 12-23 months | 147 | 9.1 (7.7-10.8) | 635 | 40.0 (37.0-43.1) | 77 | 4.8 (3.8-6.1) |

| 24-35 months | 73 | 5.0 (3.9-6.3) | 488 | 33.3 (30.5-36.3) | 41 | 2.8 (2.0-3.8) |

| 36-47 months | 38 | 2.5 (1.8-3.5) | 413 | 29.4 (26.8-32.1) | 20 | 1.2 (0.8-2.0) |

| 48-59 months | 27 | 1.5 (1.0-2.3) | 417 | 27.9 (25.2-30.7) | 17 | 1.0 (0.6-1.7) |

| Chi-square p values | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | |||

| Sex of the children | ||||||

| Male | 221 | 5.3 (4.5-6.2) | 1357 | 34.4 (32.7-36.3) | 123 | 3.0 (2.5-3.7) |

| Female | 165 | 4.4 (3.7-5.2) | 1204 | 32.9 (30.9-34.9) | 95 | 2.4 (1.9-3.0) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.116 | p = 0.200 | p = 0.130 | |||

| Underweight children | ||||||

| No | 304 | 4.8 (4.2-5.5) | 1908 | 32.4 (30.8-34.0) | 163 | 2.6 (2.2-3.1) |

| Yes | 82 | 5.1 (4.0-6.5) | 653 | 38.5 (35.8-41.3) | 55 | 3.3 (2.4-4.4) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.678 | p = 0.0001 | p = 0.170 | |||

| Birth orderof the children | ||||||

| First | 143 | 4.8 (4.0-5.7) | 909 | 31.8 (29.7-33.9) | 78 | 2.5 (2.0-3.2) |

| Second | 144 | 5.6 (4.7-6.8) | 850 | 33.9 (31.7-36.2) | 87 | 3.4 (2.6-4.3) |

| Third | 63 | 4.8 (3.7-6.1) | 454 | 35.2 (32.4-38.1) | 36 | 2.9 (2.0-4.0) |

| Fourth and above | 36 | 3.4 (2.3-4.9) | 348 | 37.0 (33.4-40.7) | 17 | 1.6 (0.9-2.8) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.088 | p = 0.036 | p = 0.057 | |||

| Small birth weight | ||||||

| No | 134 | 6.9 (5.7-8.3) | 637 | 35.1 (32.7,37.6) | 77 | 4.0 (3.1-5.0) |

| Yes | 26 | 7.7 (5.1-11.5) | 132 | 41.8 (35.6-48.2) | 12 | 4.0 (2.1-7.2) |

| Not weighted | 163 | 6.3 (5.4-7.4) | 964 | 37.4 (35.2-39.6) | 93 | 3.5 (2.8-4.4]) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.616 | p = 0.087 | p = 0.776 | |||

| Mass media exposure | ||||||

| No | 124 | 4.5 (3.6-5.6) | 952 | 34.2 (32.0-36.5) | 68 | 2.6 (1.9-3.5) |

| Yes | 262 | 5.1 (4.4-5.8) | 1609 | 33.4 (31.7-35.2) | 150 | 2.8 (2.3-3.4) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.395 | p = 0.545 | p = 0.664 | |||

| Source of water | ||||||

| Improved | 351 | 5.0 (4.5-5.7) | 2247 | 34.0 (32.5-35.5) | 195 | 2.8 (2.4-3.3) |

| Unimproved | 35 | 3.7 (2.7-5.3) | 314 | 31.6 (28.4-35.0) | 23 | 2.4 (1.5-3.7) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.089 | p = 0.180 | p = 0.486 | |||

| Type of toilet facility | ||||||

| Improved | 228 | 5.0 (4.3-5.8) | 1450 | 33.7 (31.9-35.5) | 129 | 2.8 (2.3-3.4) |

| Unimproved | 158 | 4.7 (3.9-5.6) | 1111 | 33.7 (31.8-35.7) | 89 | 2.6 (2.0-3.3) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.522 | p = 0.952 | p = 0.623 | |||

| Solid waste use in cooking | ||||||

| No | 99 | 4.2 (3.4-5.2) | 669 | 31.1 (28.8-33.6) | 56 | 2.4 (1.8-3.2) |

| Yes | 287 | 5.2 (4.5-5.9) | 1892 | 34.8 (33.1-36.5) | 162 | 2.9 (2.4-3.4) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.091 | p = 0.009 | p = 0.255 | |||

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 84 | 4.9 (3.8-6.2) | 600 | 35.0 (32.5-37.5) | 47 | 2.7 (2.0-3.8) |

| Poorer | 77 | 4.8 (3.8-6.1) | 522 | 33.5 (30.7-36.5) | 42 | 2.7 (2.0-3.7) |

| Middle | 84 | 6.1 (4.7-7.9) | 471 | 35.0 (32.0-38.1) | 45 | 3.4 (2.4-4.6) |

| Richer | 58 | 3.4 (2.6-4.5) | 537 | 35.0 (32.1-38.0) | 40 | 2.2 (1.5-3.1) |

| Richest | 83 | 5.3 (4.1-6.7) | 431 | 29.6 (26.8-32.6) | 44 | 2.7 (2.0-3.7) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 044 | p = 0.034 | p = 0.484 | |||

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 132 | 4.6 (3.7-5.7) | 805 | 31.8 (29.4-34.3) | 72 | 2.7 (2.0-3.6) |

| Rural | 254 | 5.0 (4.3-5.7) | 1756 | 34.4 (32.6-36.2) | 146 | 2.8 (2.3-3.3) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.567 | p = 0.095 | p = 0.833 | |||

| Division | ||||||

| Barisal | 51 | 6.5 (5.0-8.3) | 296 | 38.3 (34.0-42.7) | 24 | 3.1 (2.0-4.7) |

| Chattogram | 67 | 5.3 (4.1-7.0) | 412 | 33.3 (30.0-36.7) | 43 | 3.3 (2.3-4.7) |

| Dhaka | 44 | 4.1 (3.0-5.4) | 340 | 31.8 (28.5-35.2) | 19 | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) |

| Khulna | 33 | 3.9 (2.8-5.4) | 238 | 31.2 (27.1-35.6) | 18 | 2.2 (1.4-3.5) |

| Mymensingh | 47 | 5.0 (3.7-6.7) | 301 | 33.7 (29.9-37.7) | 30 | 3.2 (2.2-4.5) |

| Rajshahi | 49 | 6.1 (4.6-8.1) | 278 | 35.5 (30.9-40.3) | 29 | 3.6 (2.4-5.4) |

| Rangpur | 37 | 4.5 (3.0-6.7) | 312 | 36.4 (32.2-40.7) | 22 | 2.7 (1.6-4.4) |

| Sylhet | 58 | 4.8 (3.5-6.6) | 384 | 34.3 (31.4-37.2) | 33 | 2.9 (2.0-4.2) |

| Chi-square p values | p = 0.239 | p = 0.297 | p = 0.124 | |||

| Risk factors | Diarrhea | Fever | Coexistence of diarrhea and fever | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | p values | AOR (95% CI) | p values | AOR (95% CI) | p values | |

| Parents’ education | ||||||

| Both parents uneducated | 1.15 (0.65-2.03) | 0.626 | 0.88 (0.67-1.14) | 0.320 | 1.07 (0.52-2.21) | 0.852 |

| Only father uneducated | 0.70 (0.47-1.04) | 0.081 | 0.85 (0.72-1.00) | 0.046 | 0.51 (0.29-0.91) | 0.023 |

| Only mother uneducated | 1.87 (1.16-3.02) | 0.010 | 0.70 (0.53-0.94) | 0.016 | 1.31 (0.66-2.62) | 0.442 |

| Both parents educated® | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Mother's attitude towards wife beating | ||||||

| No® | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.63 (0.46-0.86) | 0.100 | 1.30 (1.15-1.47) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.42-0.97) | 0.033 |

| Age of the children | ||||||

| 0-11 months | 3.97 (2.49-6.32) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.35-1.83) | <0.001 | 3.77 (2.11-6.74) | <0.001 |

| 12-23 months | 6.46 (4.12-10.13) | <0.001 | 1.78(1.53-2.08) | <0.001 | 5.17 (2.94-9.12) | <0.001 |

| 24-35 months | 3.32 (2.06-5.34) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.13-1.54) | 0.001 | 2.78 (1.52-5.07) | 0.001 |

| 36-47 months | 1.64 (0.96-2.80) | 0.068 | 1.08 (0.92-1.27) | 0.346 | 1.24 (0.62-2.50) | 0.542 |

| 48-59 months® | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Underweight children | ||||||

| No® | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Yes | 1.36 (1.21-1.53) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.04-1.99) | 0.028 | ||

| Birth order of the children | ||||||

| First® | 1.00 | |||||

| Second | 1.11 (0.99-1.24) | 0.083 | ||||

| Third | 1.17 (1.02-1.35) | 0.025 | ||||

| Fourth and above | 1.27 (1.08-1.49) | 0.005 | ||||

| Source of drinking water | ||||||

| Improved® | 1.00 | |||||

| Unimproved | 0.66 (0.47-0.94) | 0.021 | ||||

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 0.92 (0.65-1.31) | 0.650 | 1.21 (1.03-1.43) | 0.018 | ||

| Poorer | 0.88 (0.62-1.25) | 0.484 | 1.13 (0.96-1.32) | 0.142 | ||

| Middle | 1.12 (0.81-1.56) | 0.487 | 1.22 (1.04-1.44) | 0.011 | ||

| Richer | 0.62 (0.43-0.89) | 0.010 | 1.23 (1.05-1.44) | 0.009 | ||

| Richest® | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Division | ||||||

| Dhaka® | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Barisal | 1.69 (1.06-2.70) | 0.027 | 1.80 (0.93-3.46) | 0.079 | ||

| Chattogram | 1.33 (0.96-1.83) | 0.085 | 1.93 (1.24-3.01) | 0.004 | ||

| Khulna | 1.02 (0.65-1.60) | 0.927 | 1.34 (0.73-2.45) | 0.345 | ||

| Mymensingh | 1.24 (0.80-1.91) | 0.336 | 1.85 (1.05-3.25) | 0.033 | ||

| Rajshahi | 1.66 (1.15-2.41) | 0.007 | 2.21 (1.34-3.64) | 0.002 | ||

| Rangpur | 1.08 (0.71-1.64) | 0.715 | 1.54 (0.89-2.66) | 0.121 | ||

| Sylhet | 1.22 (0.79-1.90) | 0.369 | 1.66 (0.93-2.97) | 0.089 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).