Submitted:

20 October 2023

Posted:

23 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Model and Medical History

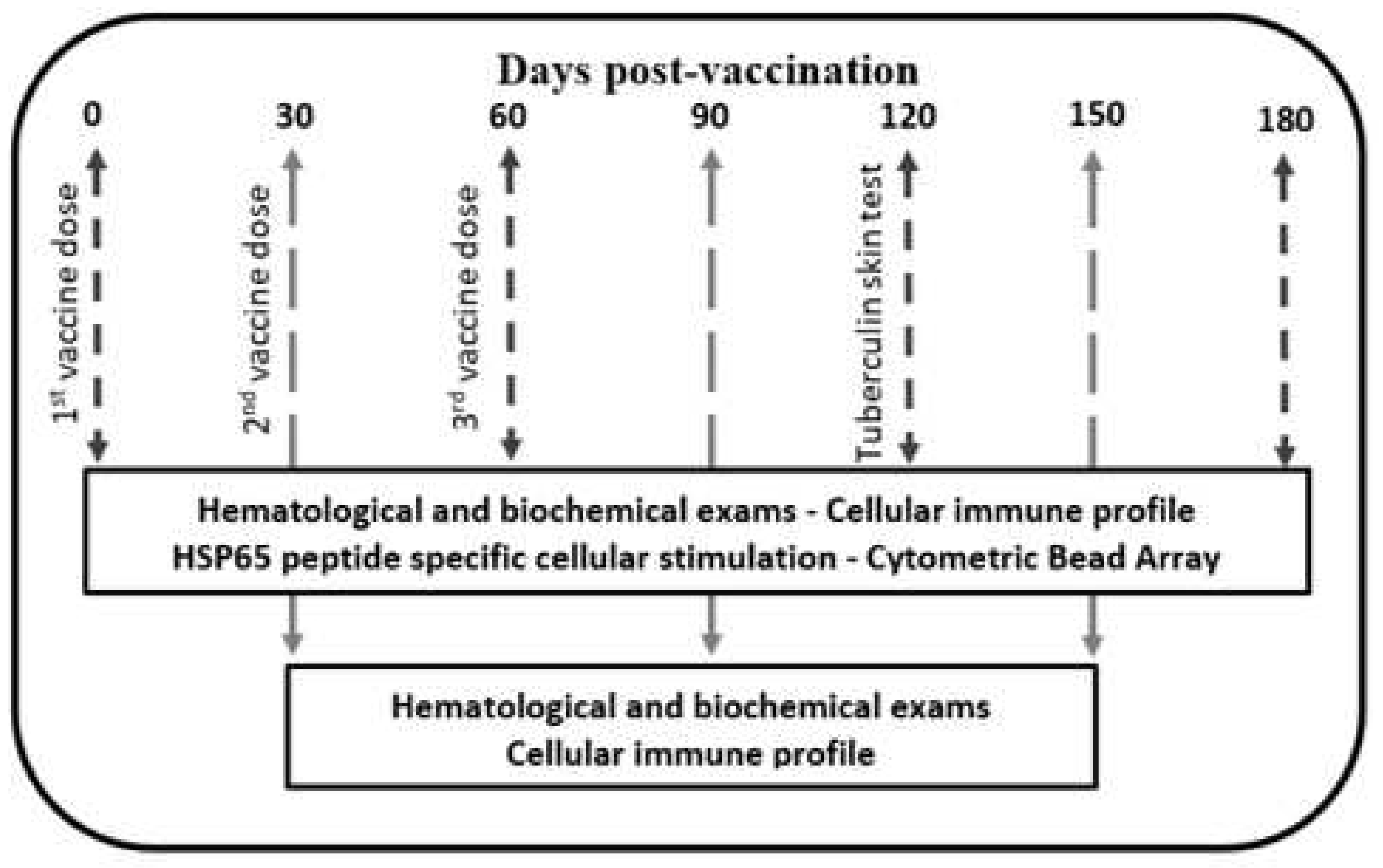

2.2. Vaccine Schedule and Electroporation

2.3. Genetic Vaccine Construction

2.4. Clinical Signs and Vaccine Safety

2.5. Cellular Immune Profile

2.6. HSP65 Peptide Specific Cellular Stimulation

2.7. Th1 and Th2 Cytokines Induced by EP-pVAX-hsp65-DNA Vaccine

2.8. Muscle and Lung Histopathology

2.9. Outcomes

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Animal Preclinical Parameters

3.2. DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine is Safe with No Adverse Events

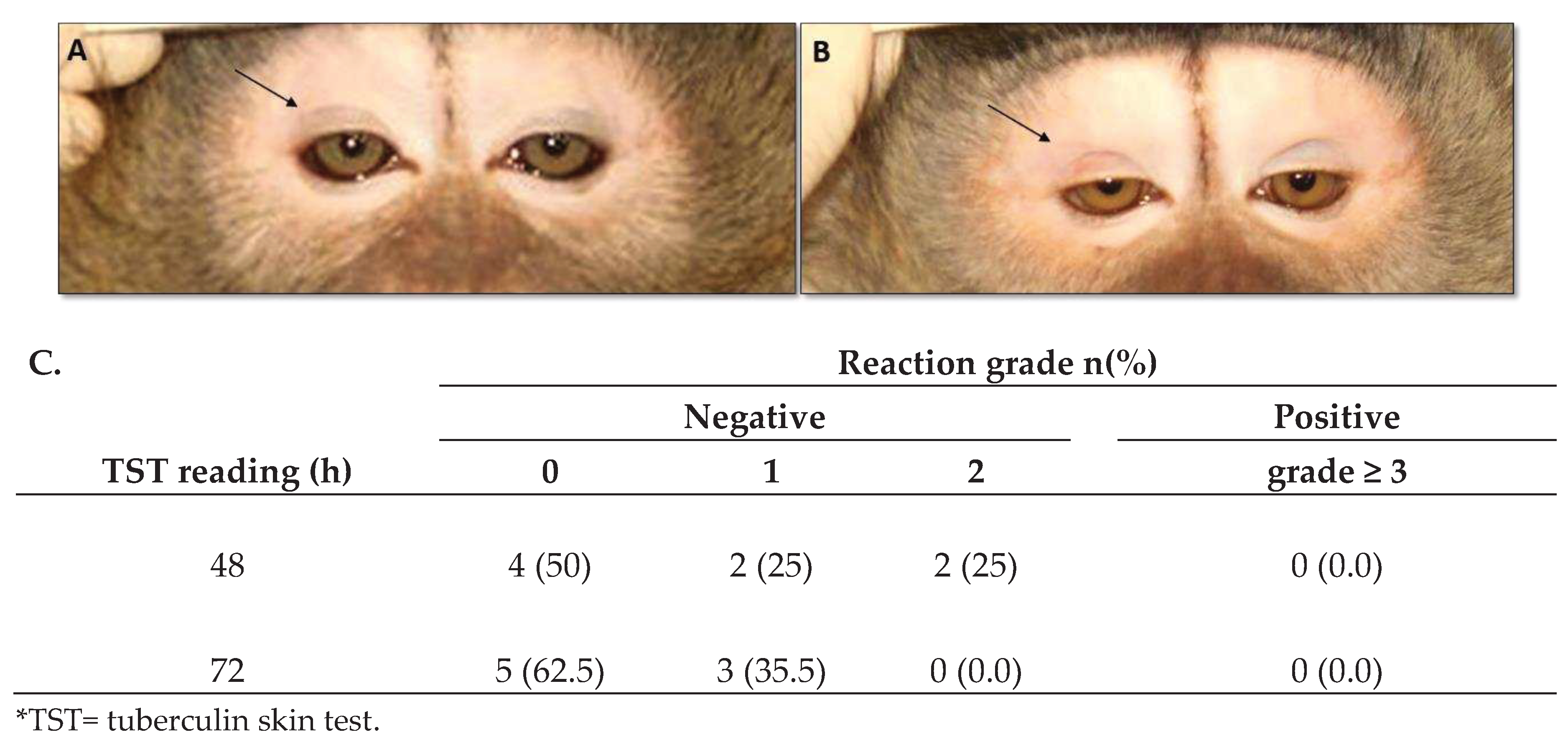

3.3. DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine Did Not Induce Tuberculin Skin Test Conversion or Pulmonary X-ray Alteration

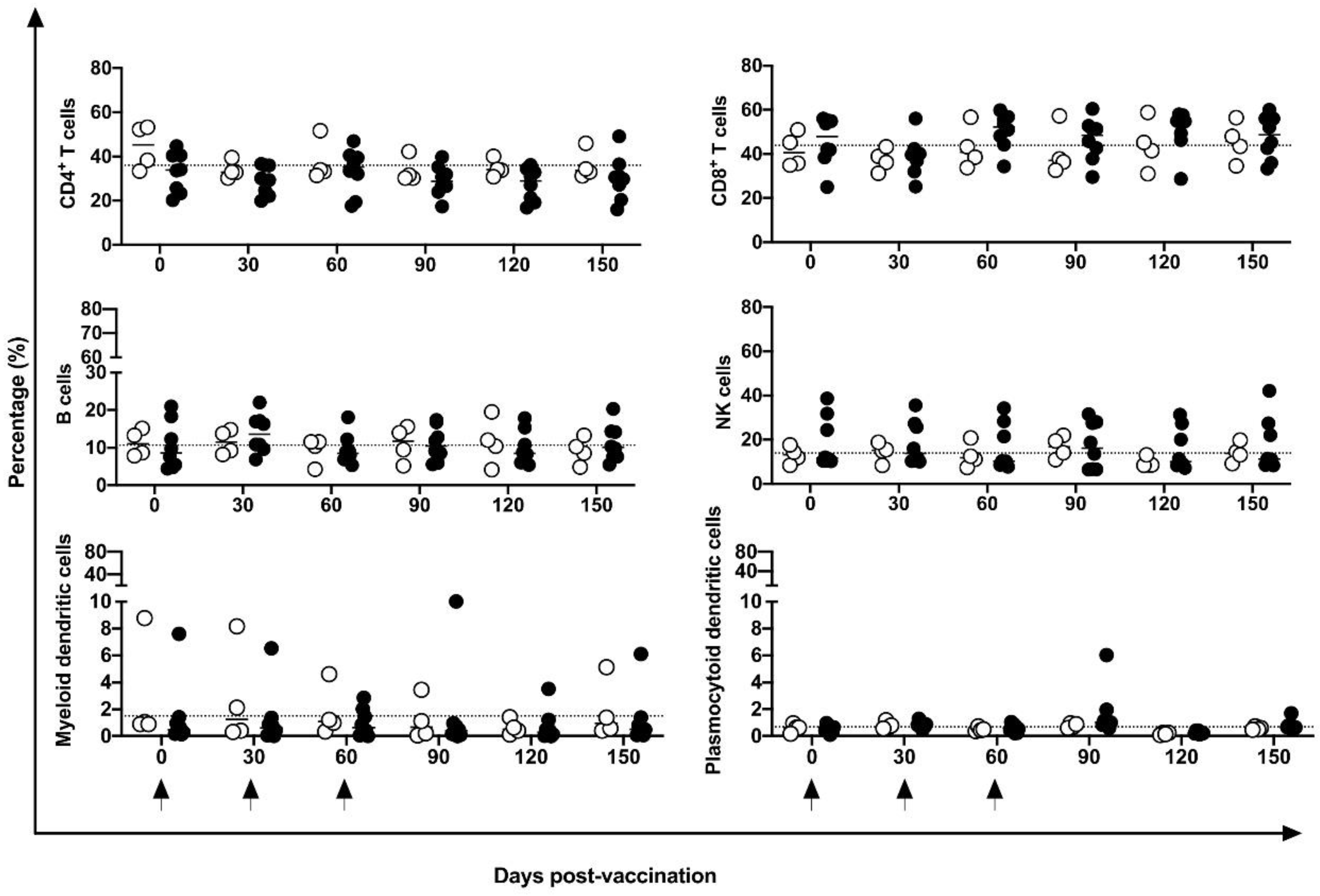

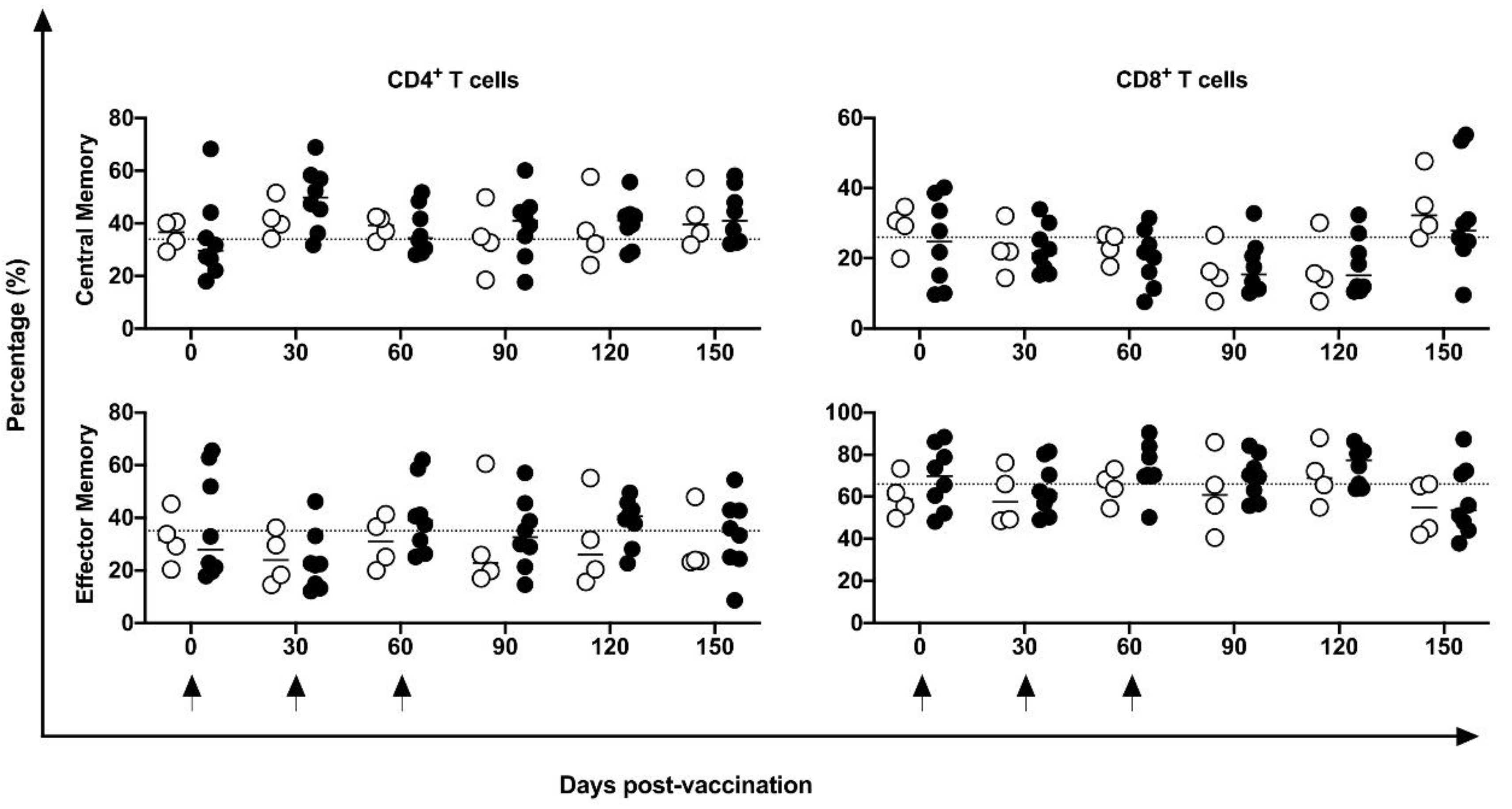

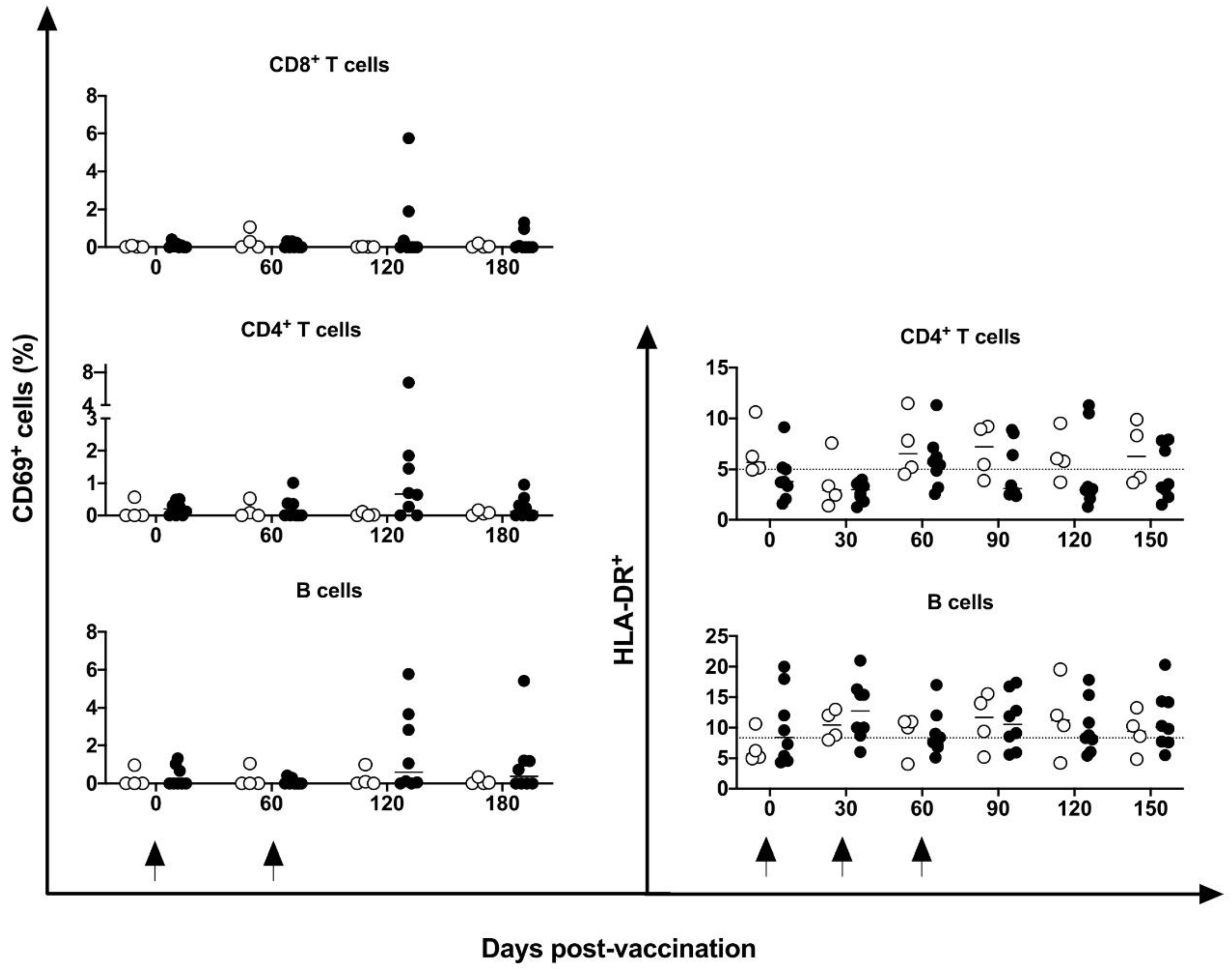

3.4. Peripheral Cell Immune Profile and Activation Markers Induced by DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine

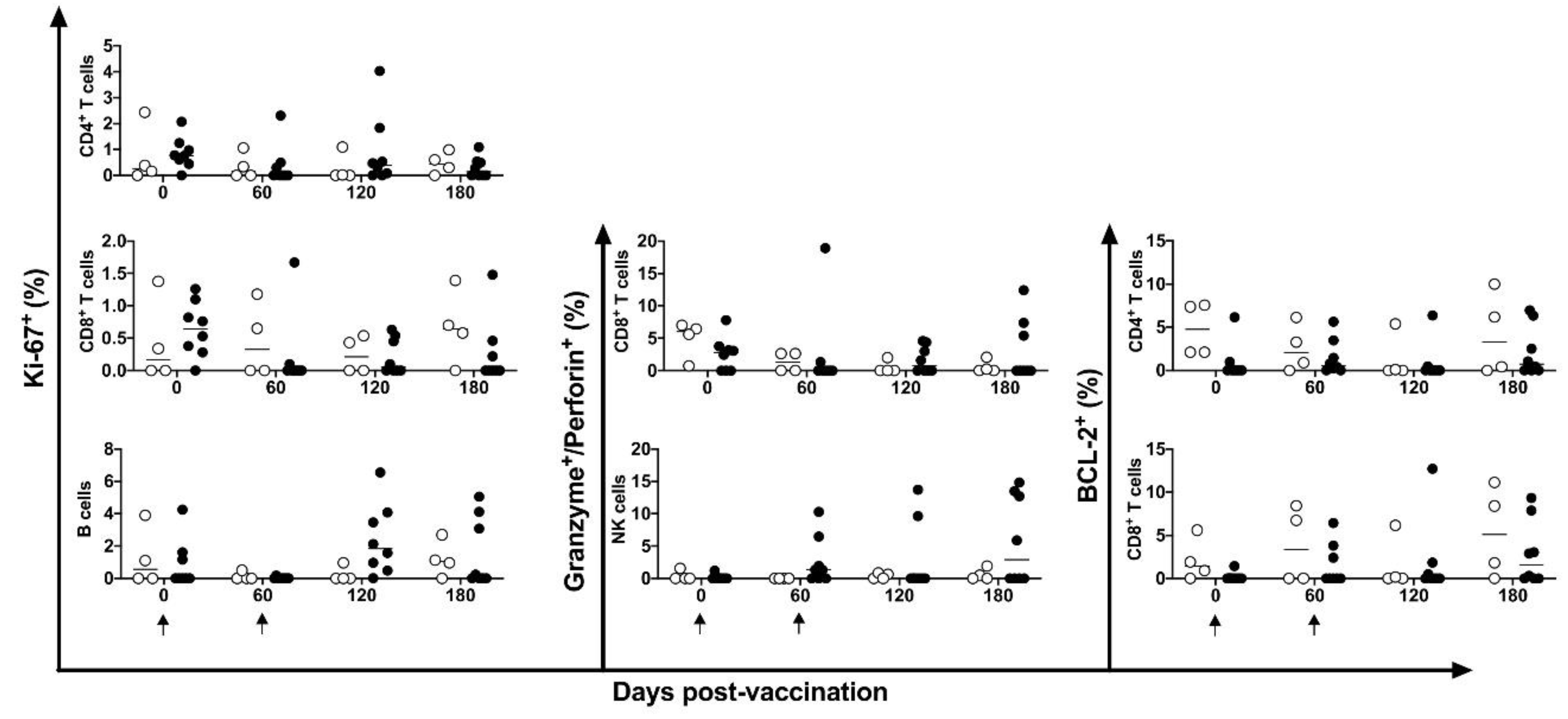

3.5. Proliferative, Lytic, and Apoptotic Markers Induced by DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine

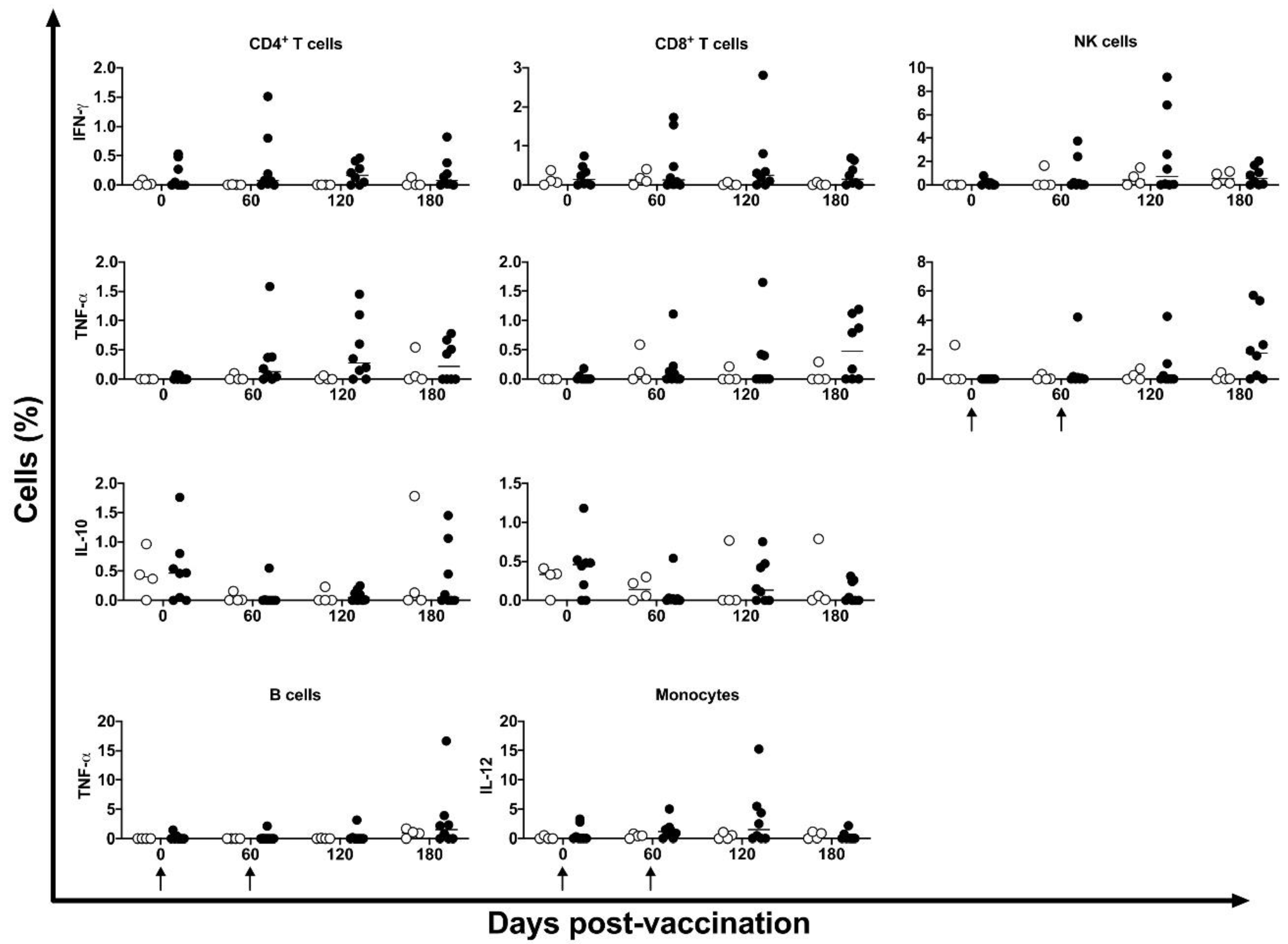

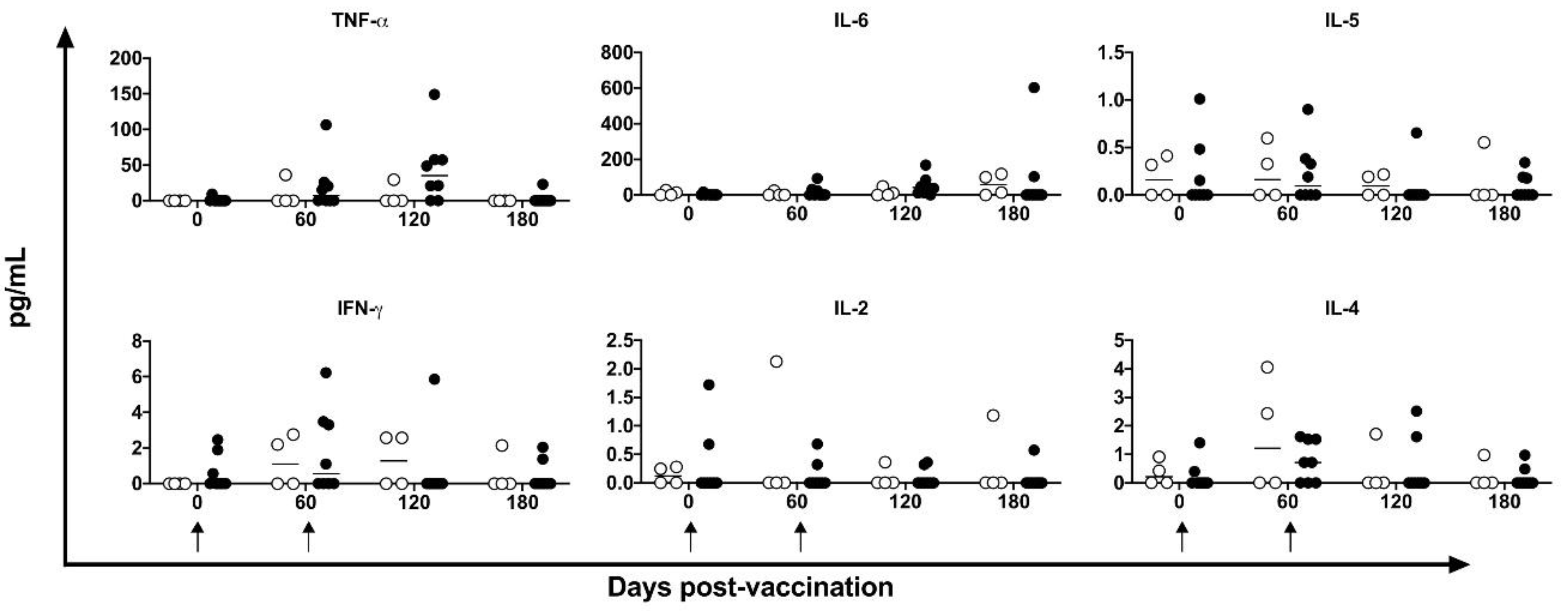

3.6. Cytokines Induced by DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine

3.7. Muscle and Lung Histopathological Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2022; 2022.

- Silva, C.L.; Malardo, T.; Tahyra, A.S.C. Immunotherapeutic Activities of a DNA Plasmid Carrying the Mycobacterial Hsp65 Gene (DNAhsp65). Front. Med. Technol. 2020, 2, 603690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrie, D.B.; Tascon, R.E.; Colston, M.J.; Silva, C.L. Towards a DNA Vaccine against Tuberculosis. Vaccine 1994, 12, 1537–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E.D.C.; Bonato, V.L.D.; da Fonseca, D.M.; Soares, E.G.; Brandão, I.T.; Soares, A.P.M.; Silva, C.L. Improve Protective Efficacy of a TB DNA-HSP65 Vaccine by BCG Priming. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 2007, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowrie, D.B.; Tascon, R.E.; Bonato, V.L.; Lima, V.M.; Faccioli, L.H.; Stavropoulos, E.; Colston, M.J.; Hewinson, R.G.; Moelling, K.; Silva, C.L. Therapy of Tuberculosis in Mice by DNA Vaccination. Nature 1999, 400, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowrie, D.B.; Silva, C.L. Enhancement of Immunocompetence in Tuberculosis by DNA Vaccination. Vaccine 2000, 18, 1712–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.F.; Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Rios, W.M.; Soares, L.S.; Souza, P.R.M.; Brandão, I.T.; Masson, A.P.; Arnoldi, F.G.C.; Ramos, S.G.; Letourneur, F.; et al. Synergy of Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy Revealed by a Genome-Scale Analysis of Murine Tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1774–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.L.; Bonato, V.L.D.; Coelho-Castelo, A. a. M.; De Souza, A.O.; Santos, S.A.; Lima, K.M.; Faccioli, L.H.; Rodrigues, J.M. Immunotherapy with Plasmid DNA Encoding Mycobacterial Hsp65 in Association with Chemotherapy Is a More Rapid and Efficient Form of Treatment for Tuberculosis in Mice. Gene Ther. 2005, 12, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, F.G.; Ito, T.; Cavassani, K.A.; Hogaboam, C.M.; Lopes Silva, C.; Kunkel, S.L.; Faccioli, L.H. Therapeutic DNA Vaccine Reduces Schistosoma Mansoni-Induced Tissue Damage through Cytokine Balance and Decreased Migration of Myofibroblasts. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 179, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, F.G.; Rosada, R.S.; Peres-Buzalaf, C.; Perusso, F.R.T.; Rodrigues, V.; Ramos, S.G.; Kunkel, S.L.; Silva, C.L.; Faccioli, L.H. Helminth Coinfection Does Not Affect Therapeutic Effect of a DNA Vaccine in Mice Harboring Tuberculosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010, 4, e700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espíndola, M.S.; Frantz, F.G.; Soares, L.S.; Masson, A.P.; Tefé-Silva, C.; Bitencourt, C.S.; Oliveira, S.C.; Rodrigues, V.; Ramos, S.G.; Silva, C.L.; et al. Combined Immunization Using DNA-Sm14 and DNA-Hsp65 Increases CD8+ Memory T Cells, Reduces Chronic Pathology and Decreases Egg Viability during Schistosoma Mansoni Infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, E.A.F.; Tavares, C.A.P.; Lima, K. de M.; Silva, C.L.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Fernandes, A.P. Mycobacterium Hsp65 DNA Entrapped into TDM-Loaded PLGA Microspheres Induces Protection in Mice against Leishmania (Leishmania) Major Infection. Parasitol. Res. 2006, 98, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Bocca, A.L.; Amaral, A.C.; Faccioli, L.H.; Galetti, F.C.S.; Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Figueiredo, F.; Silva, C.L.; Felipe, M.S.S. DNAhsp65 Vaccination Induces Protection in Mice against Paracoccidioides Brasiliensis Infection. Vaccine 2009, 27, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Bocca, A.L.; Amaral, A.C.; Souza, A.C.C.O.; Faccioli, L.H.; Coelho-Castelo, A.A.M.; Figueiredo, F.; Silva, C.L.; Felipe, M.S.S. HSP65 DNA as Therapeutic Strategy to Treat Experimental Paracoccidioidomycosis. Vaccine 2010, 28, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.M.; Ribeiro, A.M.; Nóbrega, Y.K. de M.; Simon, K.S.; Souza, A.C.O.; Jerônimo, M.S.; Cavalcante Neto, F.F.; Silva, C.L.; Felipe, M.S.S.; Bocca, A.L. DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine as Therapeutic Strategy to Treat Experimental Chromoblastomycosis Caused by Fonsecaea Pedrosoi. Mycopathologia 2013, 175, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.R.; Sartori, A.; Lima, D.S.; Souza, P.R.; Coelho-Castelo, A.A.; Bonato, V.L.; Silva, C.L. DNA Vaccine Containing the Mycobacterial Hsp65 Gene Prevented Insulitis in MLD-STZ Diabetes. J. Immune Based Ther. Vaccines 2009, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Júnior, R.R. dos; Sartori, A.; Bonato, V.L.D.; Coelho Castelo, A. a. M.; Vilella, C.A.; Zollner, R.L.; Silva, C.L. Immune Modulation Induced by Tuberculosis DNA Vaccine Protects Non-Obese Diabetic Mice from Diabetes Progression. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007, 149, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileggi, G.S.; Clemencio, A.D.; Malardo, T.; Antonini, S.R.; Bonato, V.L.D.; Rios, W.M.; Silva, C.L. New Strategy for Testing Efficacy of Immunotherapeutic Compounds for Diabetes in Vitro. BMC Biotechnol. 2016, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rosa, L.C.; Chiuso-Minicucci, F.; Zorzella-Pezavento, S.F.G.; França, T.G.D.; Ishikawa, L.L.W.; Colavite, P.M.; Balbino, B.; Tavares, L.C.B.; Silva, C.L.; Marques, C.; et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin/DNAhsp65 Prime-Boost Is Protective against Diabetes in Non-Obese Diabetic Mice but Not in the Streptozotocin Model of Type 1 Diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2013, 173, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Junior, R.R.; Sartori, A.; De Franco, M.; Filho, O.G.R.; Coelho-Castelo, A.A.M.; Bonato, V.L.D.; Cabrera, W.H.K.; Ibañez, O.M.; Silva, C.L. Immunomodulation and Protection Induced by DNA-Hsp65 Vaccination in an Animal Model of Arthritis. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005, 16, 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Narciso, C.; Pérez-Tapia, M.; Rangel-Cano, R.M.; Silva, C.L.; Meckes-Fisher, M.; Salgado-Garciglia, R.; Estrada-Parra, S.; López-Gómez, R.; Estrada-García, I. Expression of Mycobacterium Leprae HSP65 in Tobacco and Its Effectiveness as an Oral Treatment in Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis. Transgenic Res. 2011, 20, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzella-Pezavento, S.F.G.; Guerino, C.P.F.; Chiuso-Minicucci, F.; França, T.G.D.; Ishikawa, L.L.W.; Masson, A.P.; Silva, C.L.; Sartori, A. BCG and BCG/DNAhsp65 Vaccinations Promote Protective Effects without Deleterious Consequences for Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 721383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzella-Pezavento, S.F.G.; Chiuso-Minicucci, F.; França, T.G.D.; Ishikawa, L.L.W.; da Rosa, L.C.; Colavite, P.M.; Balbino, B.; Marques, C.; Ikoma, M.R.V.; Masson, A.P.; et al. PVAXhsp65 Vaccination Primes for High IL-10 Production and Decreases Experimental Encephalomyelitis Severity. J. Immunol. Res. 2017, 2017, 6257958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzella-Pezavento, S.F.G.; Chiuso-Minicucci, F.; França, T.G.D.; Ishikawa, L.L.W.; da Rosa, L.C.; Colavite, P.M.; Marques, C.; Ikoma, M.R.V.; Silva, C.L.; Sartori, A. Downmodulation of Peripheral MOG-Specific Immunity by PVAXhsp65 Treatment during EAE Does Not Reach the CNS. J. Neuroimmunol. 2014, 268, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.M.; Bonato, V.L.D.; Silva, C.L.; Sartori, A. Th1 Polarized Response Induced by Intramuscular DNA-HSP65 Immunization Is Preserved in Experimental Atherosclerosis. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2007, 40, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, R.Q.; Bertolini, T.B.; Piñeros, A.R.; Gembre, A.F.; Ramos, S.G.; Silva, C.L.; Borges, M.C.; Bonato, V.L.D. Attenuation of Experimental Asthma by Mycobacterial Protein Combined with CpG Requires a TLR9-Dependent IFN-γ-CCR2 Signalling Circuit. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2015, 45, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.M.; Wowk, P.F.; Paula, M.O.; Gembre, A.F.; Baruffi, M.D.; Fermino, M.L.; Turato, W.M.; Campos, L.W.; Silva, C.L.; Ramos, S.G.; et al. Requirement of MyD88 and Fas Pathways for the Efficacy of Allergen-Free Immunotherapy. Allergy 2015, 70, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.M.; Wowk, P.F.; Paula, M.O.; Campos, L.W.; Gembre, A.F.; Turato, W.M.; Ramos, S.G.; Dias-Baruffi, M.; Barboza, R.; Gomes, E.; et al. Recombinant DNA Immunotherapy Ameliorate Established Airway Allergy in a IL-10 Dependent Pathway. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.H.; Wowk, P.F.; Silva, C.L.; Trombone, A.P.F.; Coelho-Castelo, A.A.M.; Oliver, C.; Jamur, M.C.; Moretto, E.L.; Bonato, V.L.D. A DNA Vaccine against Tuberculosis Based on the 65 KDa Heat-Shock Protein Differentially Activates Human Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 2008, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, R.J. Functions of Heat Shock Proteins in Pathways of the Innate and Adaptive Immune System. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 5765–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wowk, P.F.; Franco, L.H.; Fonseca, D.M. da; Paula, M.O.; Vianna, É.D.S.O.; Wendling, A.P.; Augusto, V.M.; Elói-Santos, S.M.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; Silva, F.D.C.; et al. Mycobacterial Hsp65 Antigen Upregulates the Cellular Immune Response of Healthy Individuals Compared with Tuberculosis Patients. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P. Roles of Heat-Shock Proteins in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.L.; Lowrie, D.B. Identification and Characterization of Murine Cytotoxic T Cells That Kill Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 3269–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, V.L.; Lima, V.M.; Tascon, R.E.; Lowrie, D.B.; Silva, C.L. Identification and Characterization of Protective T Cells in Hsp65 DNA-Vaccinated and Mycobacterium Tuberculosis-Infected Mice. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonato, V.L.D.; Gonçalves, E.D.C.; Soares, E.G.; Santos Júnior, R.R.; Sartori, A.; Coelho-Castelo, A. a. M.; Silva, C.L. Immune Regulatory Effect of PHSP65 DNA Therapy in Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Activation of CD8+ Cells, Interferon-Gamma Recovery and Reduction of Lung Injury. Immunology 2004, 113, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.L.; Bonato, V.L.; Lima, K.M.; Coelho-Castelo, A.A.; Faccioli, L.H.; Sartori, A.; De Souza, A.O.; Leão, S.C. Cytotoxic T Cells and Mycobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 197, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.L.; Bonato, V.L.; Lima, V.M.; Faccioli, L.H.; Leão, S.C. Characterization of the Memory/Activated T Cells That Mediate the Long-Lived Host Response against Tuberculosis after Bacillus Calmette-Guérin or DNA Vaccination. Immunology 1999, 97, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Rodrigues, R.F.; Souza, P.R.M.; Rios, W.M.; Soares, L.S.; Rosada, R.S.; Brandão, I.T.; Masson, A.P.; Floriano, E.M.; Ramos, S.G.; et al. Evaluation of the Overall IFN-γ and IL-17 pro-Inflammatory Responses after DNA Therapy of Tuberculosis. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2013, 9, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontoura, I.C.; Trombone, A.P.F.; Almeida, L.P.; Lorenzi, J.C.C.; Rossetti, R. a. M.; Malardo, T.; Padilha, E.; Schluchting, W.; Silva, R.L.L.; Gembre, A.F.; et al. B Cells Expressing IL-10 MRNA Modulate Memory T Cells after DNA-Hsp65 Immunization. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2015, 48, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Bonato, V.L.D.; da Silveira, E.L.V.; Oliveira e Paula, M.; Junta, C.M.; Sandrin-Garcia, P.; Fachin, A.L.; Mello, S.S.; Cardoso, R.S.; Galetti, F.C. de S.; et al. Comprehensive Gene Expression Profiling in Lungs of Mice Infected with Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Following DNAhsp65 Immunotherapy. J. Gene Med. 2009, 11, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Silva, C.L.; Passos, G.A. The Impact of Transcriptomics on the Fight against Tuberculosis: Focus on Biomarkers, BCG Vaccination, and Immunotherapy. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011, 2011, 192630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedatto, P.F.; Sérgio, C.A.; Paula, M.O. e; Gembre, A.F.; Franco, L.H.; Wowk, P.F.; Ramos, S.G.; Horn, C.; Marchal, G.; Turato, W.M.; et al. Protection Conferred by Heterologous Vaccination against Tuberculosis Is Dependent on the Ratio of CD4(+) /CD4(+) Foxp3(+) Cells. Immunology 2012, 137, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padua, A.I. de; Silva, C.L.; Ramos, S.G.; Faccioli, L.H.; Martinez, J.A.B. Influence of a DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine on Bleomycin-Induced Lung Injury. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2008, 34, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchi, F.C.R.; Tsanaclis, A.M.C.; Moura-Dias, Q.; Silva, C.L.; Pelegrini-da-Silva, A.; Neder, L.; Takayanagui, O.M. Modulation of Angiogenic Factor VEGF by DNA-Hsp65 Vaccination in a Murine CNS Tuberculosis Model. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2013, 93, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.P.; Trombone, A.P.; Lorenzi, J.C.; Rocha, C.D.; Malardo, T.; Fontoura, I.C.; Gembre, A.F.; Silva, R.L.; Silva, C.L.; Castelo, A.P.; et al. B Cells Can Modulate the CD8 Memory T Cell after DNA Vaccination Against Experimental Tuberculosis. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 2011, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.R.M.; Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Hori, J.I.; Ramos, S.G.; Lima, D.S.; Schneider, T.; Rosada, R.S.; Torre, L.G.L.; Santana, M.H.A.; Brandão, I.T.; et al. Protective Efficacy of Different Strategies Employing Mycobacterium Leprae Heat-Shock Protein 65 against Tuberculosis. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2008, 8, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.L.; De Souza, A.O. Vaccines of the Future: From Rational Design to Clinical Development. 17-19 October 2001, Paris, France. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2002, 2, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, K.M.; dos Santos, S.A.; Santos, R.R.; Brandão, I.T.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Silva, C.L. Efficacy of DNA-Hsp65 Vaccination for Tuberculosis Varies with Method of DNA Introduction in Vivo. Vaccine 2003, 22, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosada, R.S.; de la Torre, L.G.; Frantz, F.G.; Trombone, A.P.F.; Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Fonseca, D.M.; Souza, P.R.M.; Brandão, I.T.; Masson, A.P.; Soares, E.G.; et al. Protection against Tuberculosis by a Single Intranasal Administration of DNA-Hsp65 Vaccine Complexed with Cationic Liposomes. BMC Immunol. 2008, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, K.M.; Santos, S.A.; Lima, V.M.F.; Coelho-Castelo, A. a. M.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Silva, C.L. Single Dose of a Vaccine Based on DNA Encoding Mycobacterial Hsp65 Protein plus TDM-Loaded PLGA Microspheres Protects Mice against a Virulent Strain of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Gene Ther. 2003, 10, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Souza, A.C.O.; Amaral, A.C.; Vasconcelos, N.M.; Jeronimo, M.S.; Carneiro, F.P.; Faccioli, L.H.; Felipe, M.S.S.; Silva, C.L.; Bocca, A.L. Nanobiotechnological Approaches to Delivery of DNA Vaccine against Fungal Infection. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2013, 9, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, K.M.; dos Santos, S.A.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Silva, C.L. Vaccine Adjuvant: It Makes the Difference. Vaccine 2004, 22, 2374–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberti, M.; De Melo, L.K.; Dos Santos, S.A.; Brandao, I.T.; Soares, E.G.; Silva, C.L.; Júnior, J.M.R. Prime-Boost Vaccination Based on DNA and Protein-Loaded Microspheres for Tuberculosis Prevention. J. Drug Target. 2004, 12, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Xiao, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Song, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, X. Immunogenicity and Therapeutic Effects of a Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Rv2190c DNA Vaccine in Mice. BMC Immunol. 2017, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.; Bai, Y.-L.; Kang, J.; Xu, Z.-K.; Wang, L.-M. Construction and Immunogenicity of the DNA Vaccine of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Dormancy Antigen Rv1733c. Scand. J. Immunol. 2014, 79, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, M.; Deng, G.; Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Prime-Boost Vaccination with Bacillus Calmette Guerin and a Recombinant Adenovirus Co-Expressing CFP10, ESAT6, Ag85A and Ag85B of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Induces Robust Antigen-Specific Immune Responses in Mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 3073–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poecheim, J.; Barnier-Quer, C.; Collin, N.; Borchard, G. Ag85A DNA Vaccine Delivery by Nanoparticles: Influence of the Formulation Characteristics on Immune Responses. Vaccines (Basel) 2016, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.A.; Warke, S.R.; Kalorey, D.R.; Daginawala, H.F.; Taori, G.M.; Kashyap, R.S. Comparative Evaluation of Booster Efficacies of BCG, Ag85B, and Ag85B Peptides Based Vaccines to Boost BCG Induced Immunity in BALB/c Mice: A Pilot Study. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2015, 4, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Sayedahmed, E.E.; Singh, V.K.; Mishra, A.; Dorta-Estremera, S.; Nookala, S.; Canaday, D.H.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Sastry, K.J.; et al. A Recombinant Bovine Adenoviral Mucosal Vaccine Expressing Mycobacterial Antigen-85B Generates Robust Protection against Tuberculosis in Mice. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimourpour, R.; Zare, H.; Rajabnia, R.; Yahyapour, Y.; Meshkat, Z. Evaluation of the Eukaryotic Expression of Mtb32C-Hbha Fusion Gene of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis in Hepatocarcinoma Cell Line. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2016, 8, 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, B.; Sankian, M.; Amini, Y.; Meshkat, Z. Construction of a Novel DNA Vaccine Candidate Encoding an HspX-PPE44-EsxV Fusion Antigen of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 4, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Yu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Bai, X.; Liu, C.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Q.; et al. The Treatment of Mice Infected with Multi-Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Using DNA Vaccines or in Combination with Rifampin. Vaccine 2008, 26, 4536–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruffaerts, N.; Pedersen, L.E.; Vandermeulen, G.; Préat, V.; Stockhofe-Zurwieden, N.; Huygen, K.; Romano, M. Increased B and T Cell Responses in M. Bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin Vaccinated Pigs Co-Immunized with Plasmid DNA Encoding a Prototype Tuberculosis Antigen. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Bansal, G.P.; Grasperge, B.; Martin, D.S.; Philipp, M.; Gerloff, D.; Ellefsen, B.; Hannaman, D.; Kumar, N. Comparative Functional Potency of DNA Vaccines Encoding Plasmodium Falciparum Transmission Blocking Target Antigens Pfs48/45 and Pfs25 Administered Alone or in Combination by in Vivo Electroporation in Rhesus Macaques. Vaccine 2017, 35, 7049–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Huang, X.; Yang, L.; Song, Y.; Zhu, P.; Zhou, P. In Vivo Electroporation in DNA-VLP Prime-Boost Preferentially Enhances HIV-1 Envelope-Specific IgG2a, Neutralizing Antibody and CD8 T Cell Responses. Vaccine 2017, 35, 2042–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Ewing, D.; Blevins, M.; Sun, P.; Sundaram, A.K.; Raviprakash, K.S.; Porter, K.R.; Sanders, J.W. Enhanced Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of a Tetravalent Dengue DNA Vaccine Using Electroporation and Intradermal Delivery. Vaccine 2019, 37, 4444–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Walters, J.N.; Reuschel, E.L.; Schultheis, K.; Parzych, E.; Gary, E.N.; Maricic, I.; Purwar, M.; Eblimit, Z.; Walker, S.N.; et al. Intradermal-Delivered DNA Vaccine Induces Durable Immunity Mediating a Reduction in Viral Load in a Rhesus Macaque SARS-CoV-2 Challenge Model. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Deng, Y.; Huang, B.; Han, D.; Wang, W.; Huang, M.; Zhai, C.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, R.; Zhao, Y.; et al. DNA Vaccines Expressing the Envelope and Membrane Proteins Provide Partial Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 827605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, P.; Mulligan, M.; Anderson, E.J.; Shane, A.L.; Stephens, K.; Gibson, T.; Hartwell, B.; Hannaman, D.; Watson, N.L.; Singh, K. A Phase 1, Randomized, Controlled Dose-Escalation Study of EP-1300 Polyepitope DNA Vaccine against Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria Administered via Electroporation. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5571–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-Q.; Rao, G.-R.; Wang, G.-Q.; Li, Y.-Q.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Deng, C.-L.; Mao, Q.; Li, J.; Zhao, W.; et al. Phase IIb Trial of in Vivo Electroporation Mediated Dual-Plasmid Hepatitis B Virus DNA Vaccine in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients under Lamivudine Therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpendo, J.; Mutua, G.; Nanvubya, A.; Anzala, O.; Nyombayire, J.; Karita, E.; Dally, L.; Hannaman, D.; Price, M.; Fast, P.E.; et al. Acceptability and Tolerability of Repeated Intramuscular Electroporation of Multi-Antigenic HIV (HIVMAG) DNA Vaccine among Healthy African Participants in a Phase 1 Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Suh, Y.S.; Song, Y.G.; Choi, Y.-J.; Lee, K.H.; Seo, S.H.; Song, M.; Oh, J.-W.; Kim, M.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of Two Recombinant DNA COVID-19 Vaccines Containing the Coding Regions of the Spike or Spike and Nucleocapsid Proteins: An Interim Analysis of Two Open-Label, Non-Randomised, Phase 1 Trials in Healthy Adults. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e173–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardesai, N.Y.; Weiner, D.B. Electroporation Delivery of DNA Vaccines: Prospects for Success. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011, 23, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Cui, L.; Xiao, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Ling, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, X. Immunotherapeutic Effects of Different Doses of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Ag85a/b DNA Vaccine Delivered by Electroporation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 876579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, D.O.; Walters, J.; Laddy, D.J.; Yan, J.; Weiner, D.B. Multivalent TB Vaccines Targeting the Esx Gene Family Generate Potent and Broad Cell-Mediated Immune Responses Superior to BCG. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2014, 10, 2188–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Cai, Y.; Liang, J.; Tan, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Yam, W.-C.; et al. In Vivo Electroporation of a Codon-Optimized BERopt DNA Vaccine Protects Mice from Pathogenic Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Aerosol Challenge. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2018, 113, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, Q.; Tjelle, T.E.; Mathiesen, I.; Kjeken, R.; Xiong, S. DNA Electroporation Prime and Protein Boost Strategy Enhances Humoral Immunity of Tuberculosis DNA Vaccines in Mice and Non-Human Primates. Vaccine 2006, 24, 4565–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, G.; Schaefer, M.; Doe, B.; Liu, H.; Srivastava, I.; zur Megede, J.; O’Hagan, D.; Donnelly, J.; Widera, G.; Rabussay, D.; et al. Enhancement of DNA Vaccine Potency in Rhesus Macaques by Electroporation. Vaccine 2004, 22, 2489–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, M.A.; Schroeder, C.R.; Trask, J.D.; Paul, J.R. A CUTANEOUS TEST FOR TUBERCULOSIS IN PRIMATES. Science 1939, 89, 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauduin, M.-C.; Kaur, A.; Ahmad, S.; Yilma, T.; Lifson, J.D.; Johnson, R.P. Optimization of Intracellular Cytokine Staining for the Quantitation of Antigen-Specific CD4+ T Cell Responses in Rhesus Macaques. J. Immunol. Methods 2004, 288, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, M.C.; Lee, J.C.; Daniels, S.E.; Tebas, P.; Khan, A.S.; Giffear, M.; Sardesai, N.Y.; Bagarazzi, M.L. Tolerability of Intramuscular and Intradermal Delivery by CELLECTRA(®) Adaptive Constant Current Electroporation Device in Healthy Volunteers. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2013, 9, 2246–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalams, S.A.; Parker, S.D.; Elizaga, M.; Metch, B.; Edupuganti, S.; Hural, J.; De Rosa, S.; Carter, D.K.; Rybczyk, K.; Frank, I.; et al. Safety and Comparative Immunogenicity of an HIV-1 DNA Vaccine in Combination with Plasmid Interleukin 12 and Impact of Intramuscular Electroporation for Delivery. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 208, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizaga, M.L.; Li, S.S.; Kochar, N.K.; Wilson, G.J.; Allen, M.A.; Tieu, H.V.N.; Frank, I.; Sobieszczyk, M.E.; Cohen, K.W.; Sanchez, B.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of HIV-1 Multiantigen PDNA Vaccine given with IL-12 Plasmid DNA via Electroporation, Boosted with a Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus HIV Gag Vaccine in Healthy Volunteers in a Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edupuganti, S.; C De Rosa, S.; Elizaga, M.; Lu, Y.; Han, X.; Huang, Y.; Swann, E.; Polakowski, L.; A Kalams, S.; Keefer, M.; et al. Intramuscular and Intradermal Electroporation of HIV-1 PENNVAX-GP® DNA Vaccine and IL-12 Is Safe, Tolerable, Acceptable in Healthy Adults. Vaccines (Basel) 2020, 8, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawman, D.W.; Ahlén, G.; Appelberg, K.S.; Meade-White, K.; Hanley, P.W.; Scott, D.; Monteil, V.; Devignot, S.; Okumura, A.; Weber, F.; et al. A DNA-Based Vaccine Protects against Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever Virus Disease in a Cynomolgus Macaque Model. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.A.; Wilkinson, E.R.; Shaia, C.I.; Facemire, P.R.; Bell, T.M.; Bearss, J.J.; Shamblin, J.D.; Wollen, S.E.; Broderick, K.E.; Sardesai, N.Y.; et al. A DNA Vaccine Delivered by Dermal Electroporation Fully Protects Cynomolgus Macaques against Lassa Fever. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 2902–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Reuschel, E.L.; Kraynyak, K.A.; Racine, T.; Park, D.H.; Scott, V.L.; Audet, J.; Amante, D.; Wise, M.C.; Keaton, A.A.; et al. Protective Efficacy and Long-Term Immunogenicity in Cynomolgus Macaques by Ebola Virus Glycoprotein Synthetic DNA Vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant-Klein, R.J.; Altamura, L.A.; Badger, C.V.; Bounds, C.E.; Van Deusen, N.M.; Kwilas, S.A.; Vu, H.A.; Warfield, K.L.; Hooper, J.W.; Hannaman, D.; et al. Codon-Optimized Filovirus DNA Vaccines Delivered by Intramuscular Electroporation Protect Cynomolgus Macaques from Lethal Ebola and Marburg Virus Challenges. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2015, 11, 1991–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, F.; Kaldma, K.; Sikut, R.; Culina, S.; Romain, G.; Tuomela, M.; Adojaan, M.; Männik, A.; Toots, U.; Kivisild, T.; et al. Persistent Immune Responses Induced by a Human Immunodeficiency Virus DNA Vaccine Delivered in Association with Electroporation in the Skin of Nonhuman Primates. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009, 20, 1291–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, L.C.; Richards, M.J.; Ellefsen, B.; Chau, L.; Luxembourg, A.; Hannaman, D.; Livingston, B.D.; Schmaljohn, C.S. A DNA Vaccine for Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus Delivered by Intramuscular Electroporation Elicits High Levels of Neutralizing Antibodies in Multiple Animal Models and Provides Protective Immunity to Mice and Nonhuman Primates. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristillo, A.D.; Weiss, D.; Hudacik, L.; Restrepo, S.; Galmin, L.; Suschak, J.; Draghia-Akli, R.; Markham, P.; Pal, R. Persistent Antibody and T Cell Responses Induced by HIV-1 DNA Vaccine Delivered by Electroporation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 366, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalams, S.A.; Parker, S.; Jin, X.; Elizaga, M.; Metch, B.; Wang, M.; Hural, J.; Lubeck, M.; Eldridge, J.; Cardinali, M.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an HIV-1 Gag DNA Vaccine with or without IL-12 and/or IL-15 Plasmid Cytokine Adjuvant in Healthy, HIV-1 Uninfected Adults. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, V.; Valentin, A.; Rosati, M.; Rolland, M.; Mullins, J.I.; Pavlakis, G.N.; Felber, B.K. HIV-1 Conserved Elements P24CE DNA Vaccine Induces Humoral Immune Responses with Broad Epitope Recognition in Macaques. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, D.; Foreman, T.W.; Gautam, U.S.; Alvarez, X.; Adekambi, T.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; Golden, N.A.; Johnson, A.-M.F.; Phillips, B.L.; Ahsan, M.H.; et al. Mucosal Vaccination with Attenuated Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Induces Strong Central Memory Responses and Protects against Tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, N.; Poongulali, S.; Beulah, F.E.; Akite, E.J.; Ayuk, L.N.; Bollaerts, A.; Demoitié, M.-A.; Jongert, E.; Ofori-Anyinam, O.; Van Der Meeren, O. Long-Term Safety and Immunogenicity of the M72/AS01E Candidate Tuberculosis Vaccine in HIV-Positive and -Negative Indian Adults: Results from a Phase II Randomized Controlled Trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e13120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.H.; Biermann, K.; Chen, B.; Hsu, T.; Sambandamurthy, V.K.; Lackner, A.A.; Aye, P.P.; Didier, P.; Huang, D.; Shao, L.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Live Attenuated Persistent and Rapidly Cleared Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Vaccine Candidates in Non-Human Primates. Vaccine 2009, 27, 4709–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egen, J.G.; Rothfuchs, A.G.; Feng, C.G.; Horwitz, M.A.; Sher, A.; Germain, R.N. Intravital Imaging Reveals Limited Antigen Presentation and T Cell Effector Function in Mycobacterial Granulomas. Immunity 2011, 34, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathamuthu, G.R.; Sridhar, R.; Baskaran, D.; Babu, S. Dominant Expansion of CD4+, CD8+ T and NK Cells Expressing Th1/Tc1/Type 1 Cytokines in Culture-Positive Lymph Node Tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallin, M.A.; Sakai, S.; Kauffman, K.D.; Young, H.A.; Zhu, J.; Barber, D.L. Th1 Differentiation Drives the Accumulation of Intravascular, Non-Protective CD4 T Cells during Tuberculosis. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 3091–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewinsohn, D.M.; Lewinsohn, D.A. New Concepts in Tuberculosis Host Defense. Clin. Chest Med. 2019, 40, 703–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).