Submitted:

24 October 2023

Posted:

25 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

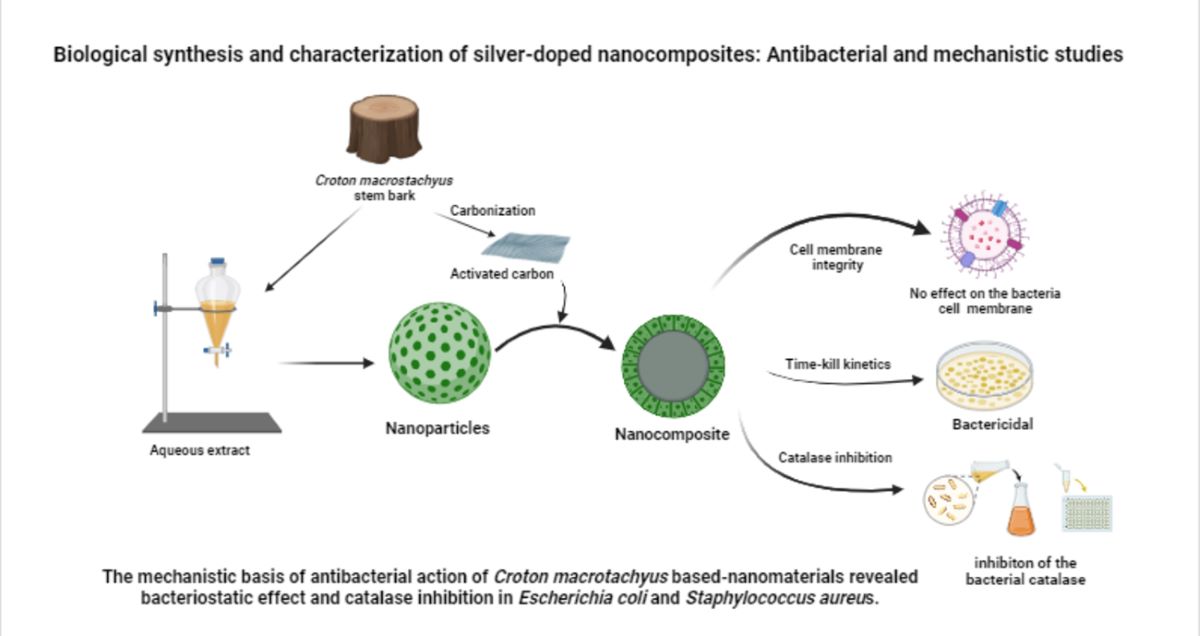

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

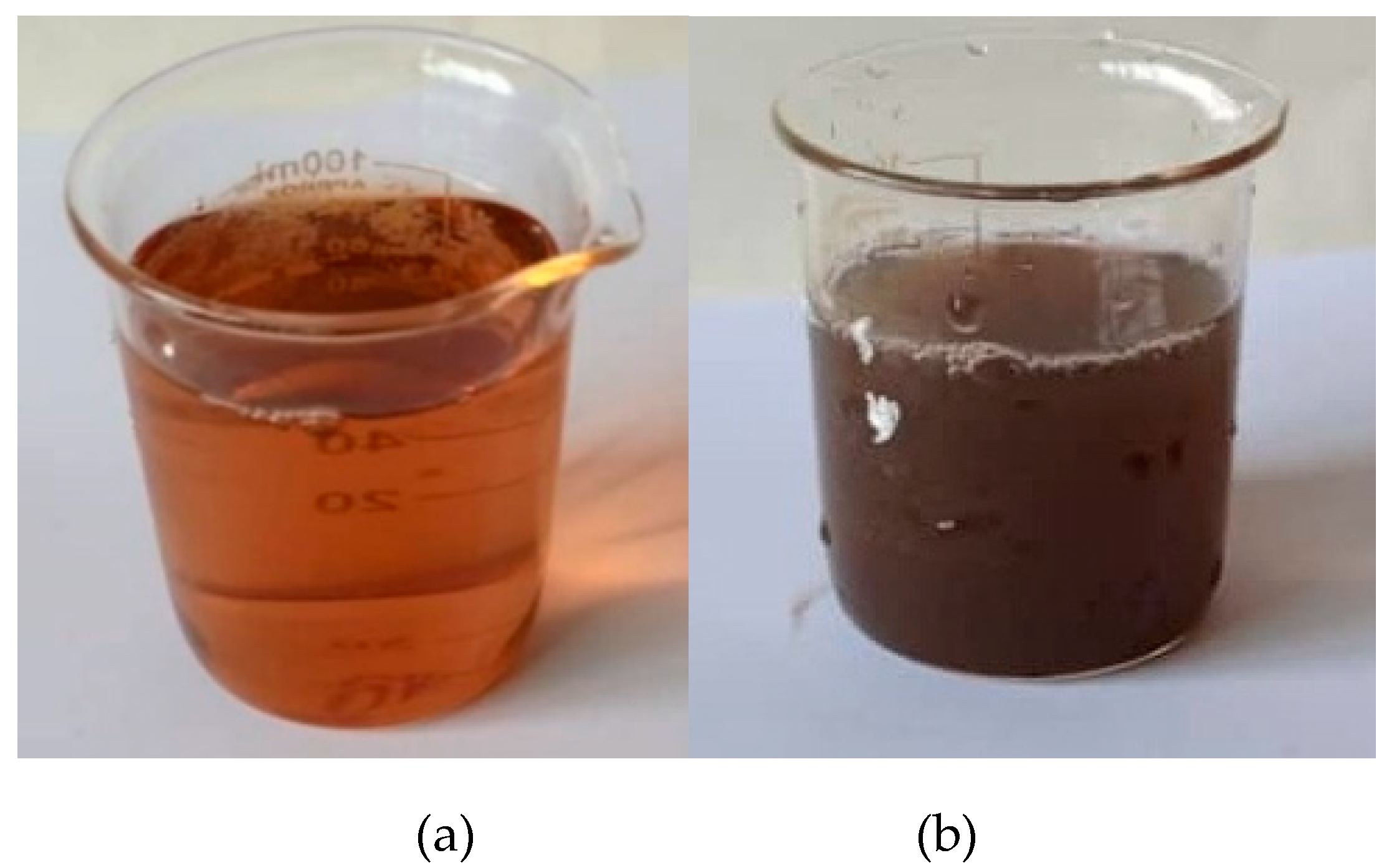

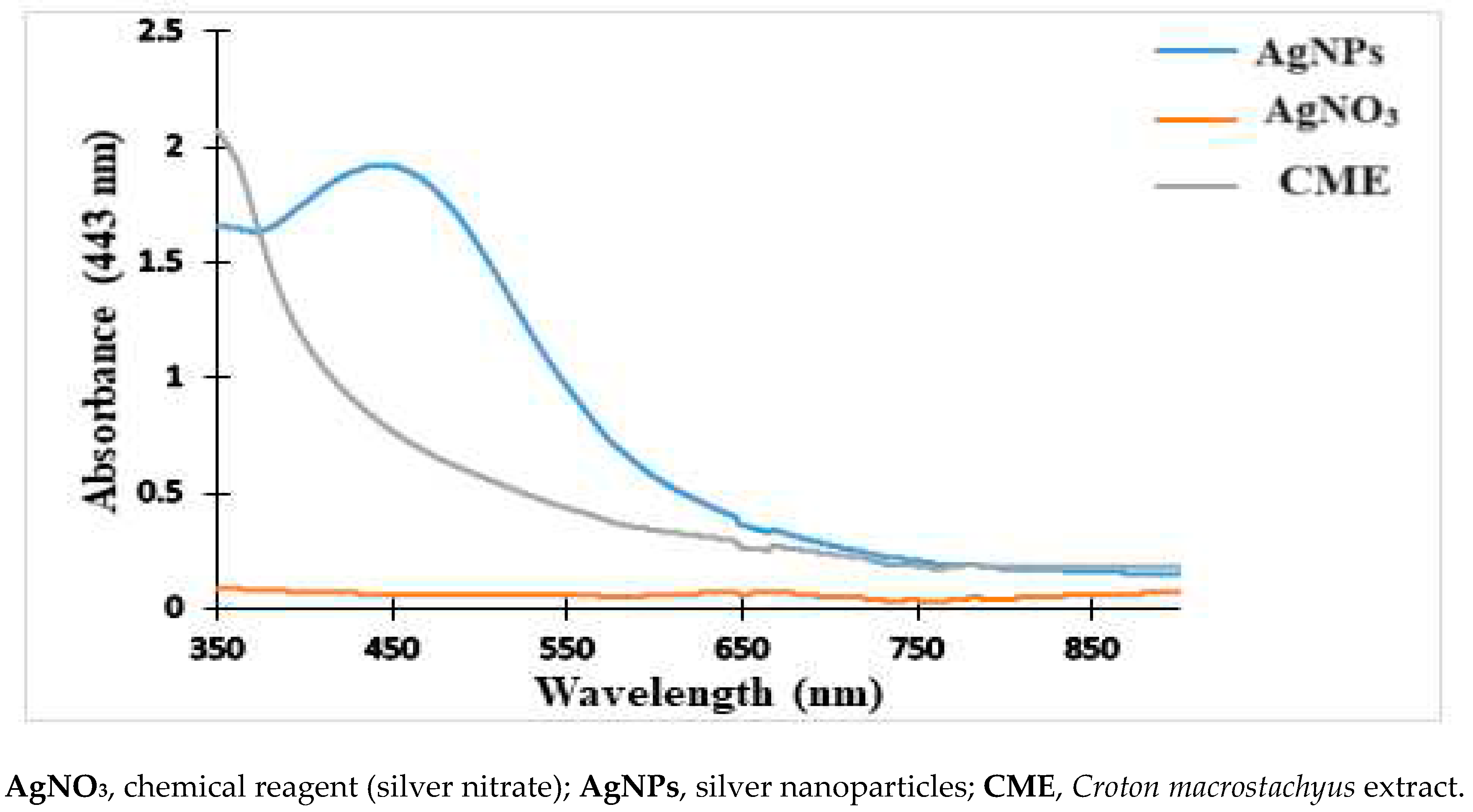

2.1. Physical and UV-Vis Analysis of the Nanoparticles

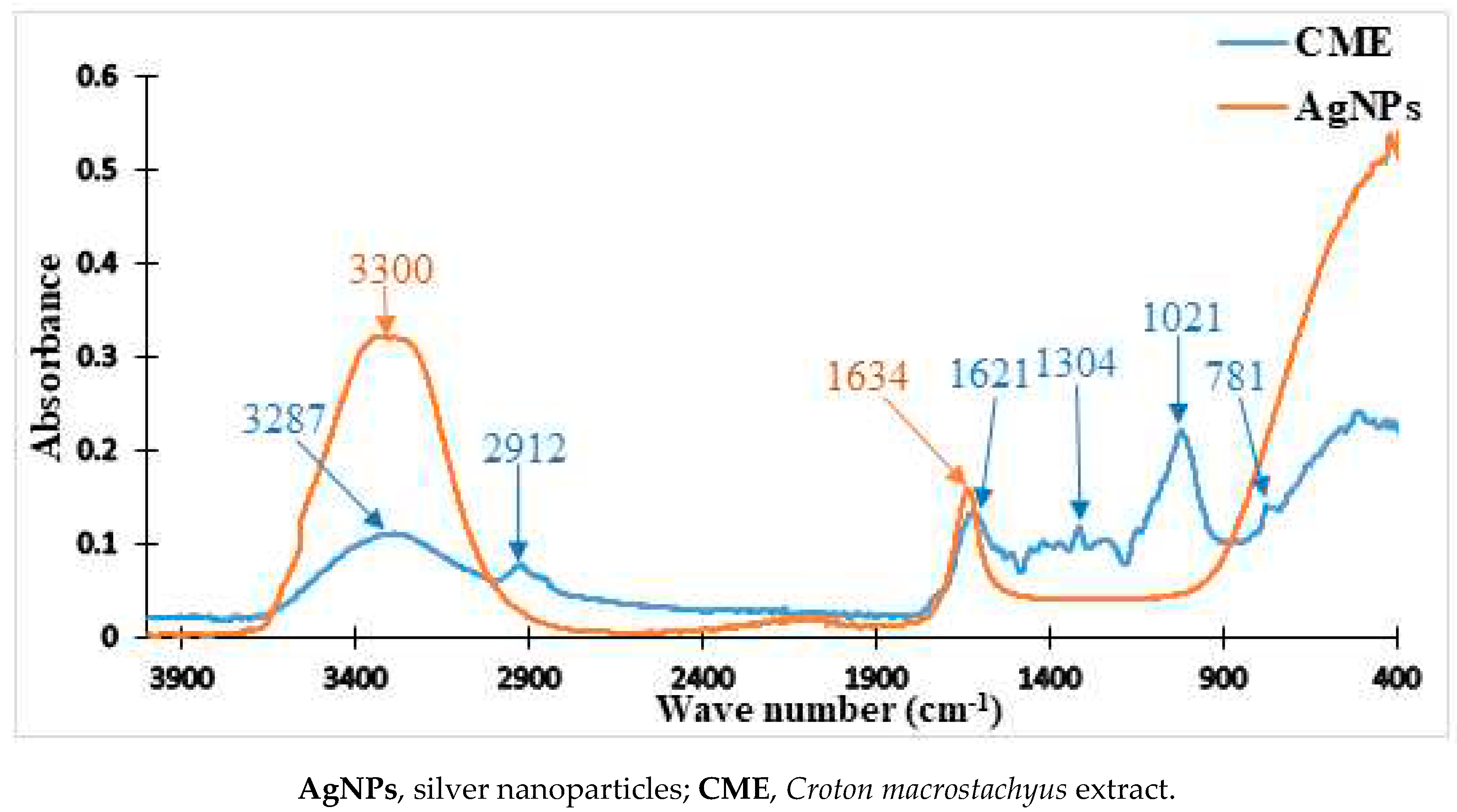

2.2. FTIR Analysis C. Macrostachyus Extract and the Nanoparticles

2.3. Characterization of the As-Prepared Activated Carbon and Nanocomposite

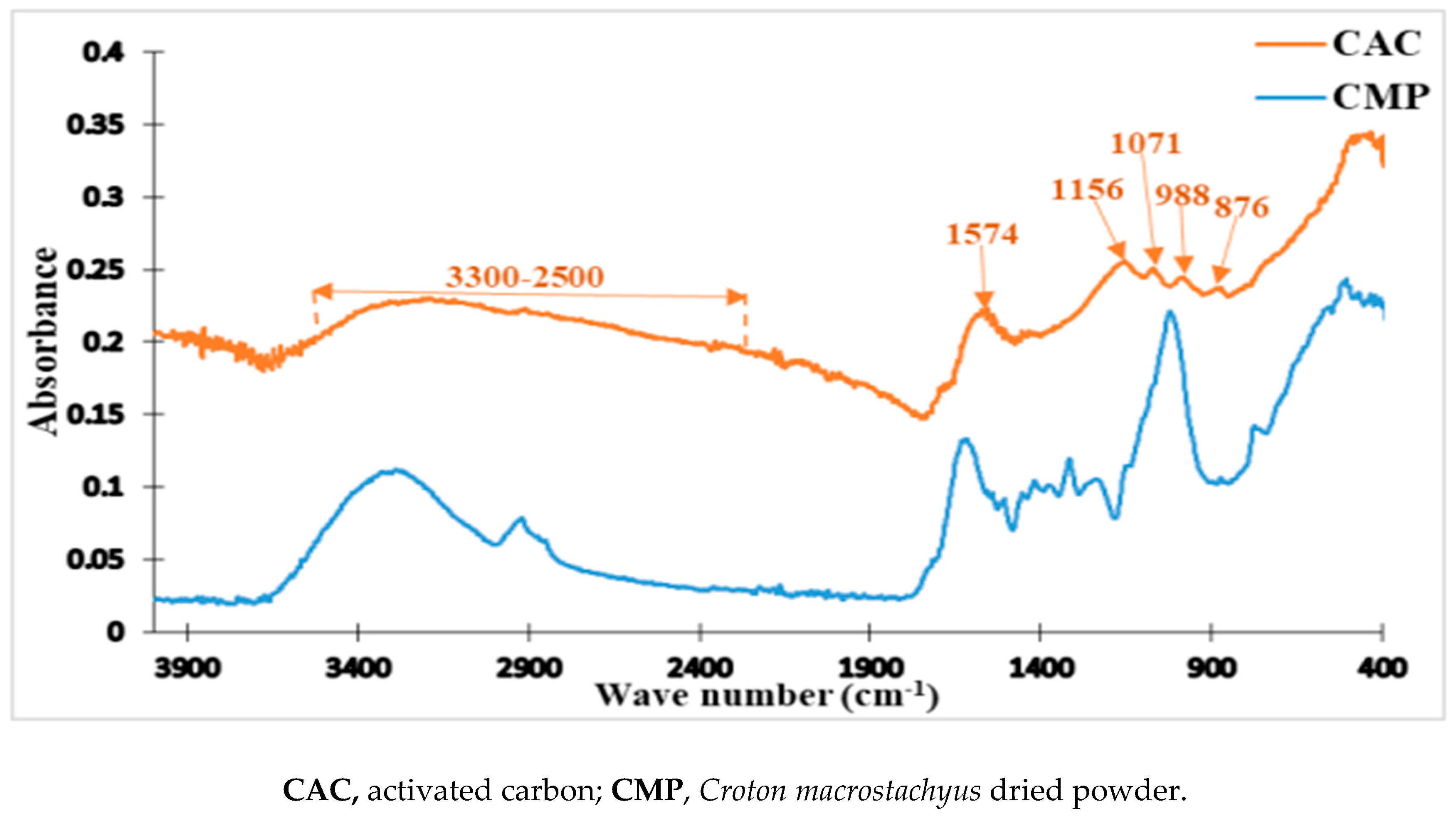

2.3.1. FTIR of the Activated Carbon

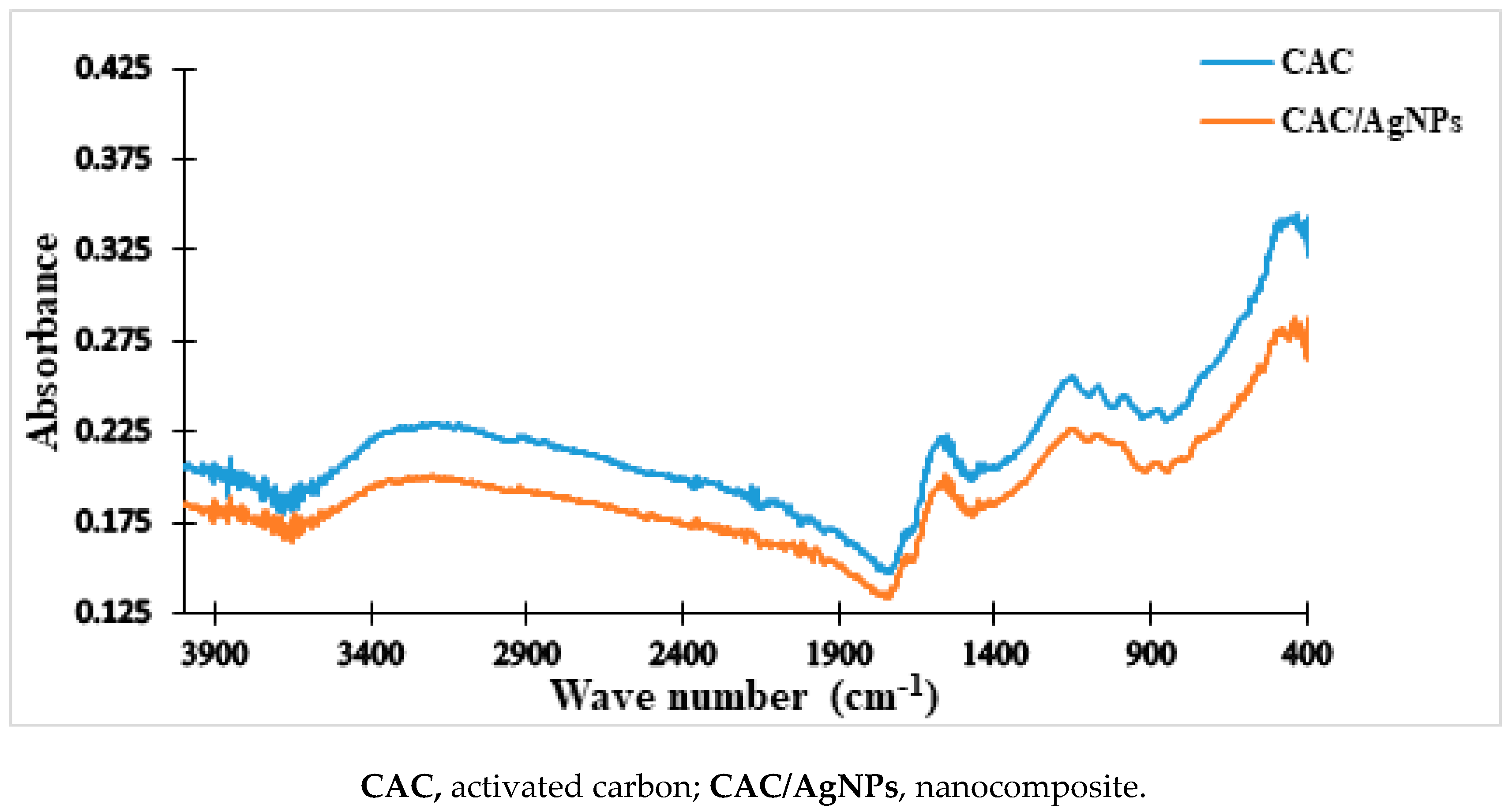

2.3.2. FTIR of the Doped-Activated Carbon (Nanocomposite)

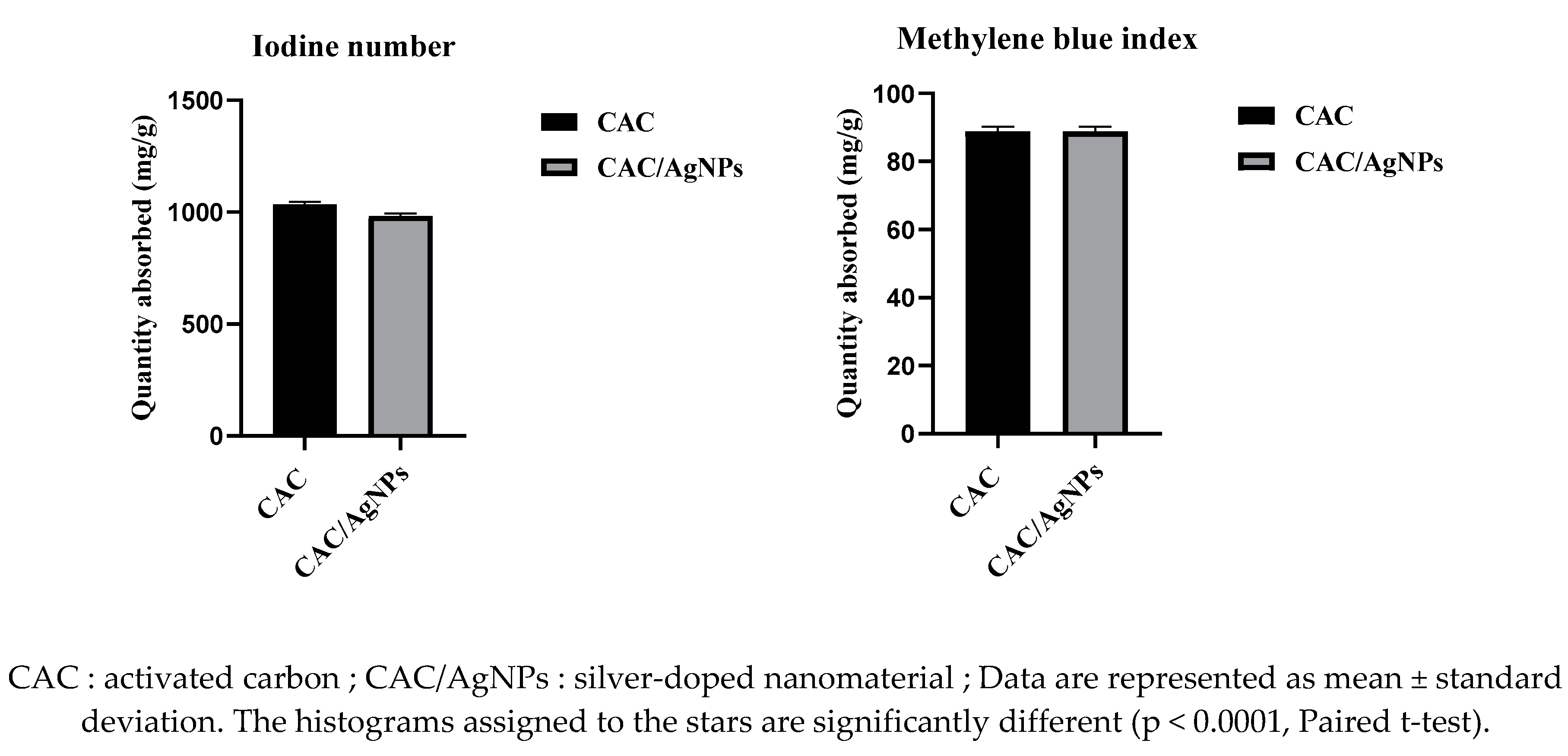

2.3.3. Iodine Number and Methylene Blue Index

2.4. Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activity

2.4.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

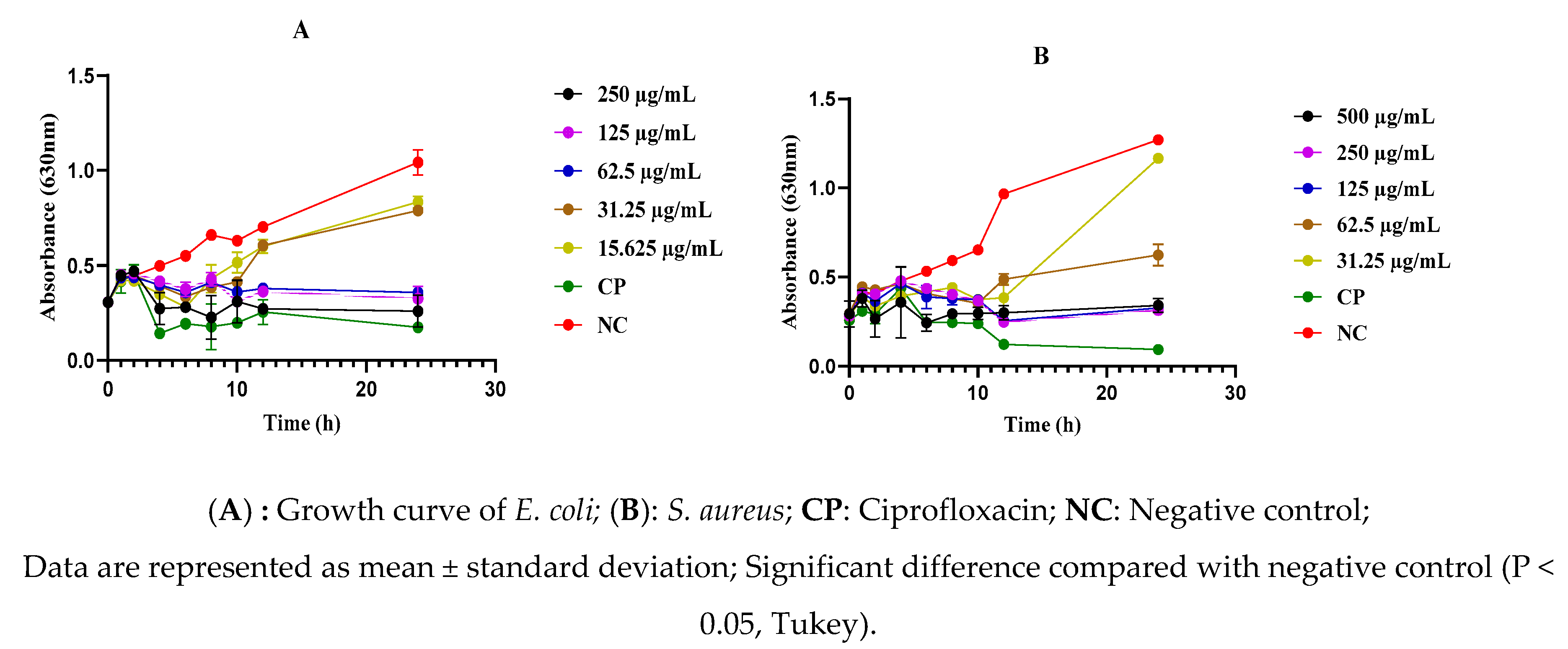

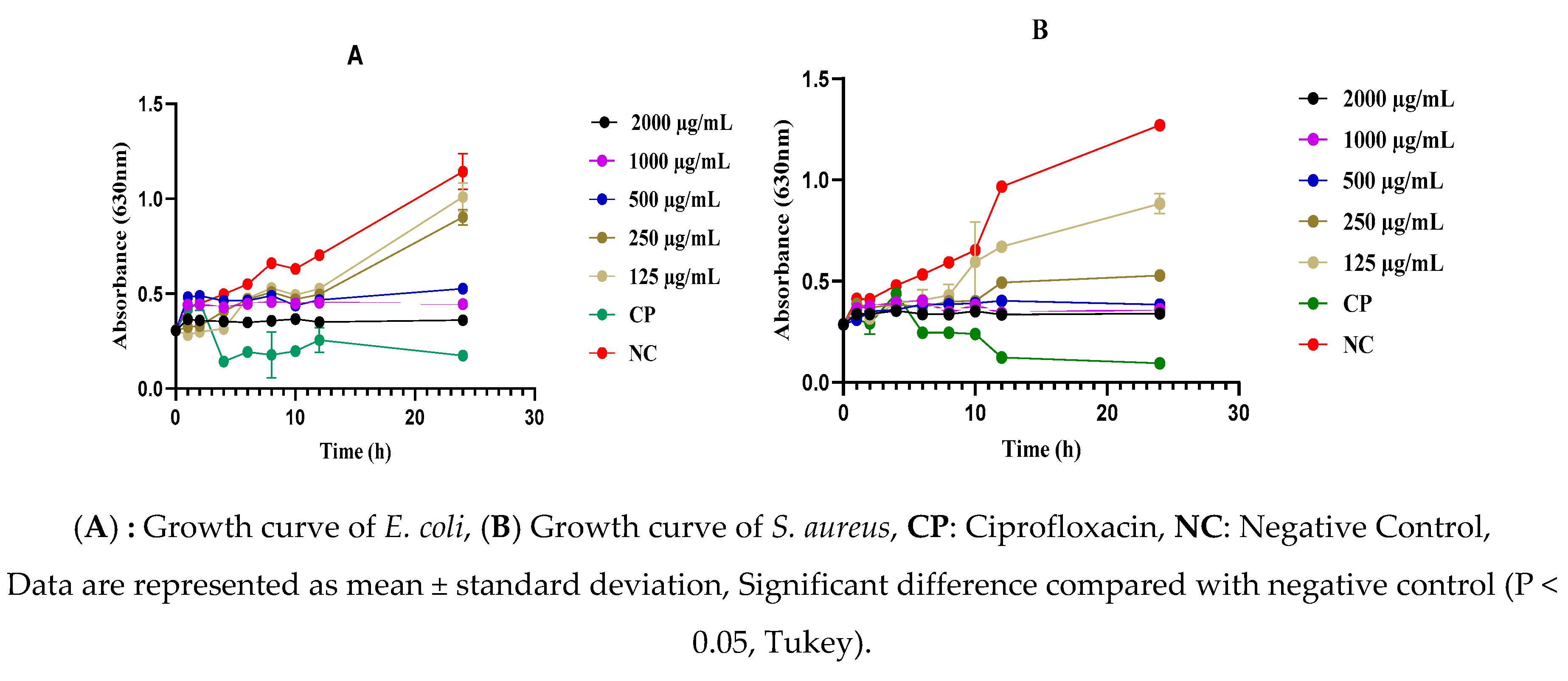

2.5. Effect of the As-Prepared Nanomaterials on the Mortality Kinetics of S. aureus and E. coli

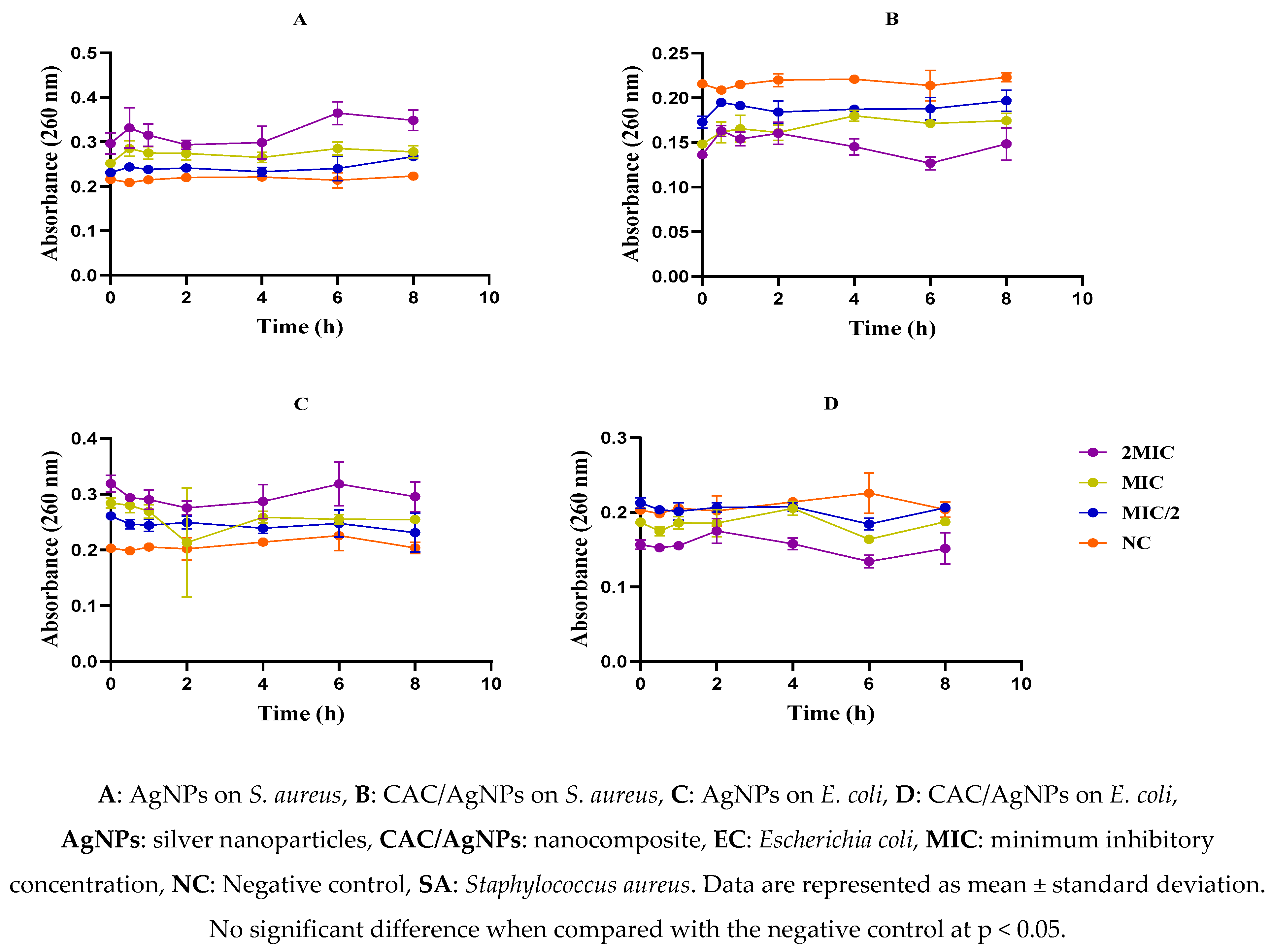

2.6. Effect of Nanomaterials on the Membrane Integrity of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus

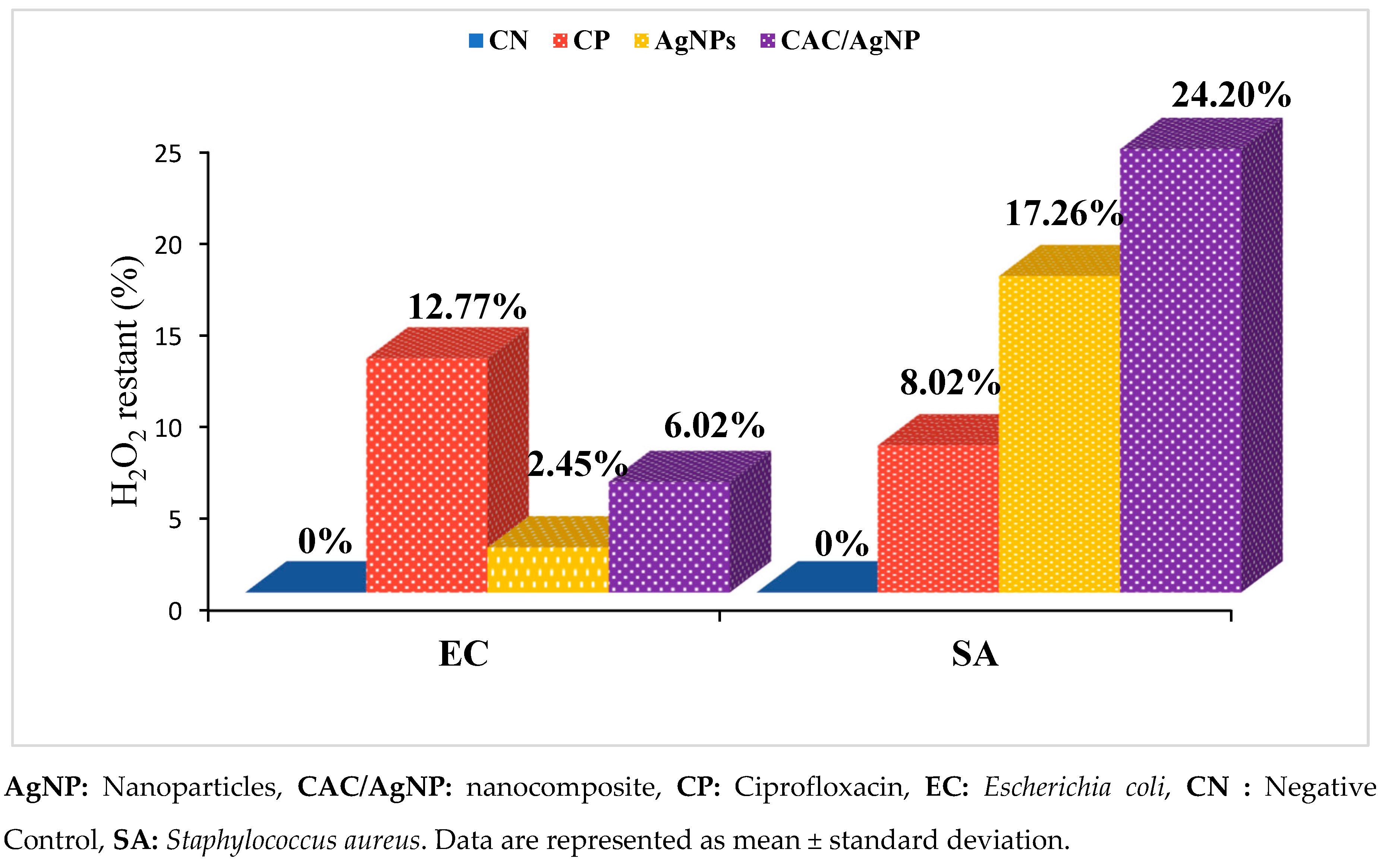

2.7. Catalase Inhibition Assay of the Nanomaterials

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Plant Collection and Identification

3.2. Plant Extraction

3.3. Preparation of Activated Carbon from Croton Macrostachyus

3.4. Biological Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Using Croton Macrostachyus

3.4.1. Preparation of Silver Nanoparticles

3.4.2. Characterization of AgNPs

3.4.2.1. UV-Vis Spectrophotometry Analysis

3.4.2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis of AgNPs

3.5. Preparation and Characterization of Nanocomposite from Croton Macrostachyus

3.5.1. Preparation of the Nanocomposite

3.5.2. Characterization of the Adsorbents Activated Carbon and Nanocomposite

3.5.3. Determination of the Methylene Blue Index and Iodine Number

3.5.3.1. Determination of the Iodine Number Using Batch Mode Adsorption

3.5.3.2. Determination of the Methylene Blue Index Using Batch Mode Adsorption

3.6. Antibacterial Activity

3.7. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations

3.8. Cytotoxicity Assays

3.9. Potential Mechanistic Studies of the Most Potent Nanomaterials

3.9.1. Bacterial Growth Kinetics on Various Concentrations of the Nanomaterials

3.9.2. Nucleic Acid Leakage Assays

3.9.3. Catalase Inhibition Assay

3.9.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The World Health Organization (WHO), 2023a. Shigella. The Fact Sheets. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/diseases/shigella (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Cleveland Clinic (CC), 2023. Infectious diseases. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17724-infectious-diseases accessed on (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- The World Health Organization (WHO), 2023b. The Key Facts. Antibiotic resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Reygaert, W.C. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neu, H.C.; Gootz, T.D. Basis of Antimicrobial Action; General Concepts; Medical Microbiology. Chapter 11: Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996, 1-17.

- Jeśman, C.; Młudzik, A.; Cybulska, M. Historia odkrycia antybiotyków i sulfonamidów [History of antibiotics and sulphonamides discoveries]. Pol. Merkur. Lekarski. 2011, 30, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, M.K. Antimetabolites : Antibiotics that inhibit nucleotide synthesis. Book Chapter. Chemistry of Antbiotics and Related Drugs. 2016, pp 109–123.

- Estrada, A.; Wright, D.L.; Anderson, A.C. Antibacterial antifolates: From development through resistance to the next generation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016, 6, a028324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.F.; Mobashery, S. β-Lactams from the Ocean. Mar Drugs 2023, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.W.; Zuccotto, F.; Bates, R.H.; Martinez-Martinez, M.S.; Read, K.D.; Peet, C.; Epemolu, O. Pharmacokinetics of β-lactam antibiotics: Clues from the past to help discover long-acting oral drugs in the future. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambau, E.; Guillard, T. Antimicrobials that affect the synthesis and conformation of nucleic acids. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2012, 31, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Villa, D.; Aguilar, M.R.; Rojo, L. Folic acid antagonists: Antimicrobial and immunomodulating mechanisms and applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Mankin, A.S. Macrolide antibiotics in the ribosome exit tunnel: species-specific binding and action. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1241, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Wang, W.; Arshad, M.I.; Khurshid, M.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.H.; Nisar, M.A.; Alvi, R.F.; Aslam, M.A.; Qamar, M.U.; Salamat, K.F.; Baloch, Z. Antibiotic resistance: a rundown of a global crisis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Jayaraman, N.; Chatterji, D. Small-molecule inhibition of bacterial biofilm. ACS Omega 2020, 5(7), 3108–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO methods and data sources for global burden of disease estimates 2000-2011. Geneva: Department of Health Statistics and Information Systems,2013.

- Tang, S.; Zheng, J. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: Structural effects. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 1701503, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugboko, H.U.; Nwinyi, O.C.; Oranusi, S.U.; Fatoki, T.H.; Omonhinmin, C.A. 2020. Antimicrobial importance of medicinal plants in Nigeria. Sci. World J. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, E.M.; Alhatlani, B.Y.; Menezes, R. de P.; Martins, C.H.G. Back to nature: Medicinal plants as promising sources for antibacterial drugs in the post-antibiotic era. Plants 2023, 12, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mody, V.V.; Siwale, R.; Singh, A.; Mody, H.R. Introduction to metallic nanoparticles. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2010, 2, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomuansangi, R.; Singh, B.P.; Singh, G.; Puia, Z.; Singh, P.K.; Song, J.J.; Kharat, A.S.; Deka, P.; Yadav, M.K. Chapter 14 - Role of nanoparticles in the treatment of human disease: a comprehensive review. Nanotechnology and Human Health. Current Research and Future Trends. Nanotechnology in Biomedicine. 2023, 381–404. [Google Scholar]

- Makvandi, P.; Wang, C.y.; Zare, E.N.; Borzacchiello, A.; Niu, L.n.; Tay, F.R. Metal-based nanomaterials in biomedical applications: Antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity aspects. Adv. Funct. Mat. 2020, 30, 1910021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, D.; Haris, M.S.; Taher, M.; Khotib, J. Natural products-based metallic nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolai, J.; Mandal, K.; Jana, N.R. Nanoparticle size effects in biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Nano. Mater. 2021, 4, 6471–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandraker, S.K.; Kumar, R. Biogenic biocompatible silver nanoparticles: a promising antibacterial agent. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2022, 2, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakal, T.C.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, R.S.; Yadav, V. Mechanistic basis of antimicrobial actions of silver nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franci, G.; Falanga, A.; Galdiero, S.; Palomba, L.; Rai, L.; Morelli, G. , Galdiero, M. Silver nanoparticles as potential antibacterial agents. Molecules, 2015, 20, 8856–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1227–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Tatsumi, D.; Kondo, T. Preparation of carbon nanoparticles from activated carbon by aqueous counter collision. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongener, C.; Kibami, D.; Rao, K.S.; Goswamee, R.L.; Sinha, D. Adsorption studies of fluoride by activated carbon prepared from Mucuna prurines plant. J. Water Chem. Technol. 2017, 39, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchacka, E.; Pstrowska, K.; Bryk, M.; Maciejowski, F.; Kułażyński, M.; Chojnacka, K. The properties of activated carbons functionalized with an antibacterial agent and a new SufA protease inhibitor. Materials (Basel) 2023, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Bautista-Toledo, I.; Ferro-Garca, M.A.; Moreno-Castilla, C. 2001. Activated carbon surface modifications by adsorption of bacteria and their effect on aqueous lead adsorption. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2001, 76, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balashanmugam, P.; Kalaichelvan, P.T. Biosynthesis characterization of silver nanoparticles using Cassia roxburghii DC. aqueous extract, and coated on cotton cloth for effective antibacterial activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10 Suppl 1, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibawa, P.J.; Nur, M.; Asy'ari, M.; Wijanarka, W.; Susanto, H.; Sutanto, H.; Nur, H. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles immobilized on activated carbon nanoparticles: Antibacterial activity enhancement study and its application on textiles fabrics. Molecules 2021, 26, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameen, F.; Karimi-Maleh, H.; Darabi, R.; Akin, M.; Ayati, A.; Ayyildiz, S.; Bekmezci, M.; Bayat, R.; Fatih, S. Synthesis and characterization of activated carbon supported bimetallic Pd based nanoparticles and their sensor and antibacterial investigation. Environ. Res. 2023, 221, 115287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sastry, M.; Mayya, K.S.; Bandyopadhyay, K. pH Dependent changes in the optical properties of carboxylic acid derivatized silver colloidal particles. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. And Engi. Aspect 1997, 127, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiravan, V.; Ravi, S.; Ashokkumar, S.; Velmurugan, S.; Elumalai, K.; Khatiwada, C.P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Croton sparsiflorus morong leaf extract and their antibacterial and antifungal activities. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 139, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, R.T. Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Croton bonplandianum Baill and its antioxidant activity. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2015, 4, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Oladotun, P.B.; Anuoluwa, A.A.; Adeyemi, A.O.; Williams, A.B.; Benson, N.U. Dataset on phytochemical screening, FTIR and GC-MS characterisation of Azadirachta indica and Cymbopogon citratus as reducing and stabilising agents for nanoparticles synthesis. Data Br. 2018, 20, 917–926. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen,, G. ; Ashfaq, A.; Khawar, A.; Jamil, Q.A.; Parveen, R.; Hadi, F.; Ghauri, O.; Shirazi, J.H.; Asif, H.M.; Shamin, T.; Sumreen, L.; Ali, T.; Akram, M.; Noor, R.; Mehmood, A.; Sajid, F. Fourier transform infrared spectrometer analysis and antimicrobial screening of ethanolic extract of Operculina terpathum from cholistan desert. Pharm. Pract. (Granada) 2022, 20, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wongsa, P.; Phatikulrungsun, P.; Prathumthong, S. FT-IR characteristics, phenolic profiles and inhibitory potential against digestive enzymes of 25 herbal infusions. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, V.; Deepa, B.; Nima, P.; Astalakhmi. Bio-inspired synthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Millingtonia hortensis. Int. J. Adv. Biotechnol. Res. 2014, 5, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Moteriya, P.; Chanda, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles formation from Caesalpinia pulcherrima stem metabolites and their broad spectrum biological activities. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, K.A.; Mahmoud, S.Y.; Ali, A. .; Almaary, K.S.; Mustafa, A.B.Z.M.A.; Husseiny, S.M. 2017. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Rhizopus stolonifer. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Odogu, A.N.; Daouda, K.; Keilah, L.P.; Tabi, G.A.; Rene, L.N.; Nsami, N.J.; Mbadcam, K.J. Effect of doping activated carbon based Ricinodendron heudelotti shells with AgNPs on the adsorption of indigo carmine and its antibacterial properties. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 5241–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radičić, R.; Maletić, D.; Blažeka, D.; Car, J.; Krstulović, N. 2022. Synthesis of silver, gold, and platinum doped zinc oxide nanoparticles by pulsed laser ablation in water. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tensay, G.K.; Zenebe, T.M.; Ameha, K.; Chaithanya, K.K. Phytochemical screening and evaluation of antibacterial activities of Croton macrostachyus stem bark extracts. Drug Invent. Today 2018, 10, 2727–2733. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.; Aslam, Z.; Shawabkeh, R.A.; Asghar, A.; Hussein, I.A. BET, FTIR, and RAMAN characterizations of activated carbon from waste oil fly ash. Turk. J. Chem. 2020, 44, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaleh, B.; Fakhri, P. Chapter 5: Infrared and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for nanofillers and their nanocomposites. In Spectroscopy of Polymer Nanocomposites. 2016, 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Asey, M.N.; Esa, N.M.; Abdullah, C.A.C. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) and MNP-chitosan composites. Malaysian J. Sci. Tech. 2019, 4, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Khatton, A.; Sarker, J.; Sikder, H.A.; Chowdhury, A.M.S. 2022. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from Jute stick by chemical activation: Comparison of different activating agents. Saudi J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 7, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, E.R.; Thakur, M.A.B.; Chaudhari, A.R. 2022. Comparative study of preparation and characterization of activated carbon obtained from sugarcane bagasse and rice husk by using H3PO4 and ZnCl2. Mater. Today: Proc. 2022, 66, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar]

- Altammar, K.A. A review on nanoparticles: characteristics, synthesis, applications, and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndi, N.J.; Ketcha, M.J.; Anagho, G.S.; Ghogomu, N.J.; Belibi, E. Physical and chemical characteristics of activated carbon prepared by pyrolysis of chemically treated cola nut (Cola acuminata) shells wastes and its ability to adsorb organics. Int. J. Adv.Chem.Technol. 2014, 2014, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; Karki, B.; Lekhak, B.; Koirala, A.R.; Sharma, R.K.; Pant, H.R. Comparative antibacterial study of silver nanoparticles doped activated carbon prepared by different methods. J. Inst. Eng. 2018, 15, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abongta, M.L. Effect of carbonization and doping on the antibacterial and antioxidant potentials of Cola acuminata shells. Master’s Thesis, University of Yaoundé I, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-López, E.; Gomes, D.; Esteruelas, G.; Bonilla, L.; Lopez-Machado, A.L.; Galindo, R.; Cano, A.; Espina, M.; Ettcheto, M.; Camins, A.; Silva, A.M.; Durazzo, A.; Santini, A.; Garcia, M.L.; Souto, E.B. Metal-based nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: An overview. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengzhu, L.; Yuchao, L.; Sie, C.T. Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 449. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdal, M.; Gurkok, S. Recent advances in nanoparticles as antibacterial agent. ADMET DMPK 2022, 10, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, T.; Patani, B.; Israel, M. Nanomaterials and cell interactions: A review. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 8, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca-Cabrera, L.; Fraga-García, P.; Berensmeier, S. Bio-nano interactions: binding proteins, polysaccharides, lipids and nucleic acids onto magnetic nanoparticles. Biomater. Res. 2021, 25, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basavegowda, N.; Baek, K.H. Multimetallic nanoparticles as alternative antimicrobial agents: Challenges and perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbekou, I.K.; Dize, D.; Yimgang, V.L.; Djague, F.; Toghueo, R.M.K. , Norbert, S.; Lenta, B.N.; Boyom, F.F. Antibacterial and mode of action of extracts from endophytic fungi derived from Terminalia mantaly, Terminalia catappa, and Cananga odorata. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, J.W. Non-heme manganese catalase–the “other” catalase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 525, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Yin, S.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Fan, K.; Pan, G. The richness and diversity of catalases in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasehir, K.E.M.; Yahaya, M.F.; Ismail, A.; Mohd, A.A. Effect of preparation conditions of activated carbon prepared from rice husk by ZnCl2 activation for removal of Cu (II) from aqueous solution. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2010, 10, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard—Ninth Edition M07 A9. Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute. 2012, 29, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, T.; Mercer, L.; Don, R.; Jacobs, R.; Nare, B. (2012). Drugs and drug resistance application of a resazurin-based high-throughput screening assay for the identification and progression of new treatments for human African trypanosomaisis. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug. Resist. 2012, 2, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguimatsia, F.; Kenmogne, S.B.; Ngo-Mback, M.N.; Kouamouo, J.; Tchuitio, N.L.; Melogmo, D.Y.; Dongmo, J.P.M. Antibacterial activities of the essential oil and hydroethanolic extract from Aeollanthus heliotropioides Oliv. Mediterr. J. Chem. 2021, 97, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, C.F.; Mee, B.J.; Riley, T.V. Mechanism of action of Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil on Staphylococcus aureus determined by time-kill, lysis, leakage, and salt tolerance assays and electron microscopy Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 1914–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MICs (µg/mL) | CC50s (µg/mL) | Selectivity indices (SI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | S. flexneri | S. sonnei | S. enteridis | S. aureus | |||

| CME | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | |

| CAC | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | 396.5 ± 3.11 | ND |

| AgNPs | 62.5 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 164.75 ± 12.51 | ~2.64 |

| CAC/AgNP | 125 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 250 | 213.6 ± 1.41 | ~1.70 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.078 | 0.078 | 0.078 | 0.156 | 0.039 | - | |

| Podophyllotoxin | 0.4 ± 0.1 | ||||||

| Bacterial strains | Acronym | Reference number | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Escherichia coli Salmonella enteridis Shigella flexneri Shigella sonnei Staphylococcus aureus |

E. coli S. enteridis S. flexneri S. sonnei S. aureus |

ATCC 25922 Isolat NR 518 NR 519 ATCC 43300 |

ATCC CPC BEI resources BEI resources ATCC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).