Submitted:

25 October 2023

Posted:

25 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Organizational Readiness

2.2. The Organizational Readiness of Hotels for the Integration of Local Agri-Food Products

2.3. Perceived Benefits and Intention to Introduce Local Agro-Food Products in Hotel Menus

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Hotel Profile

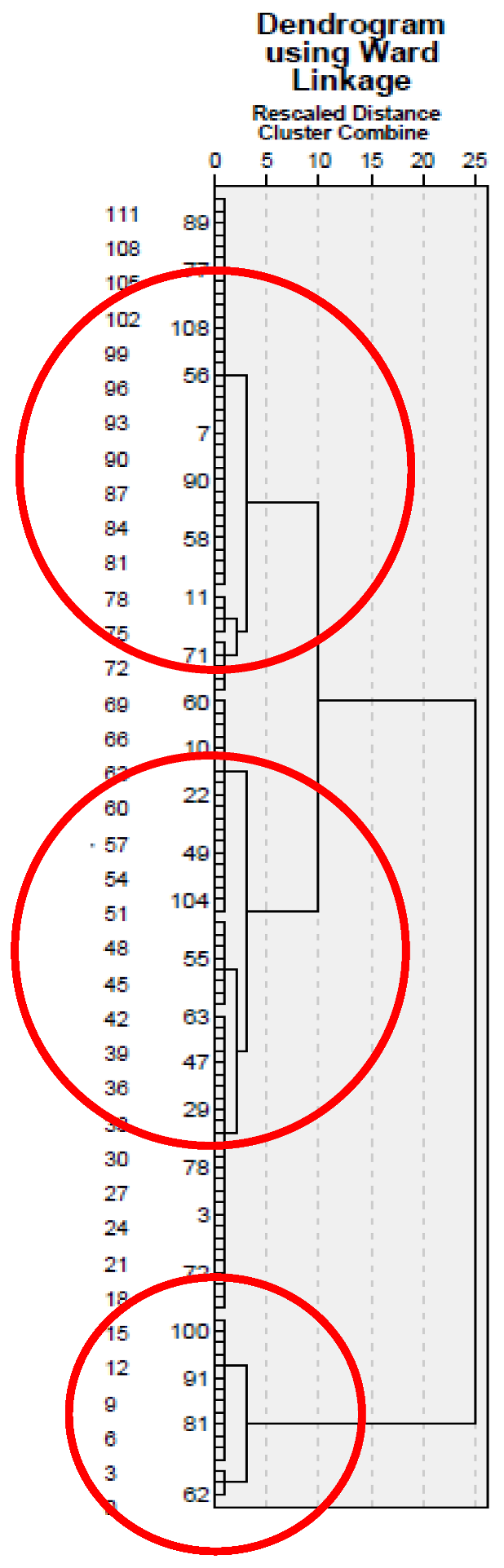

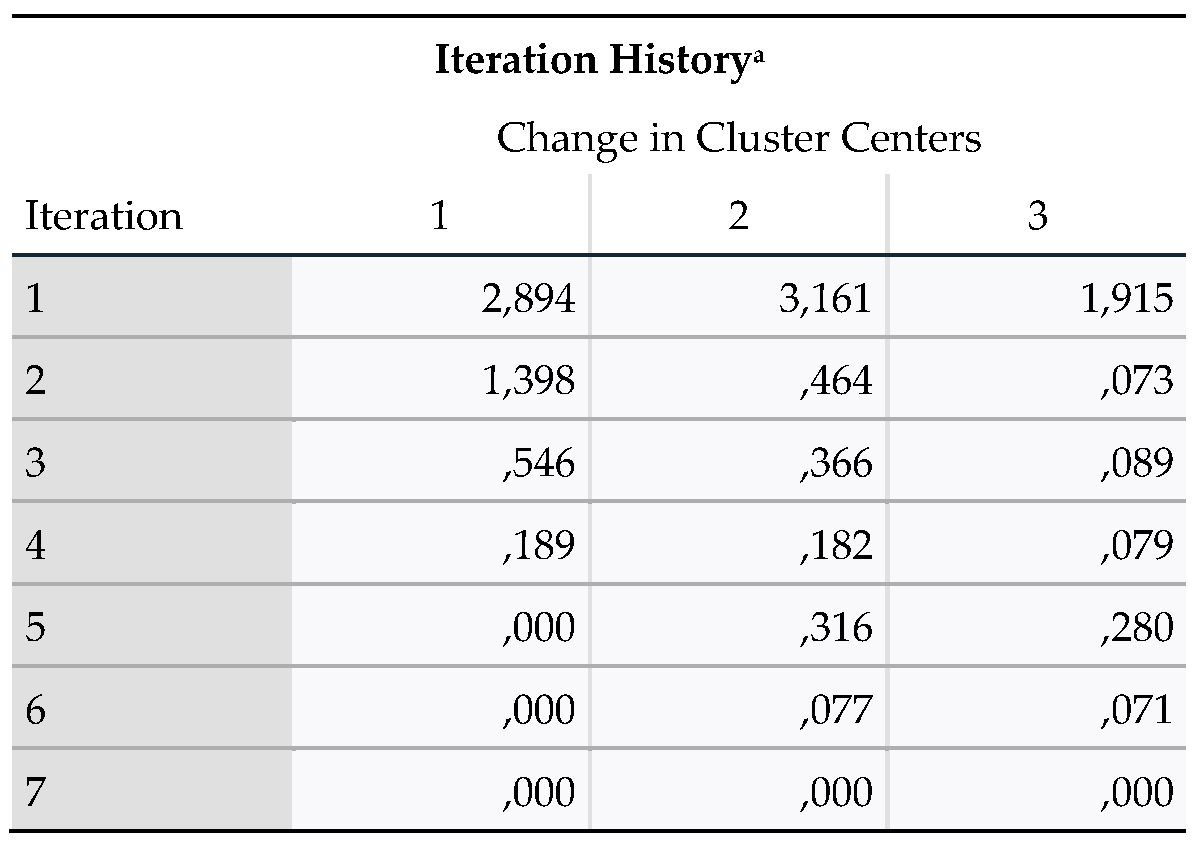

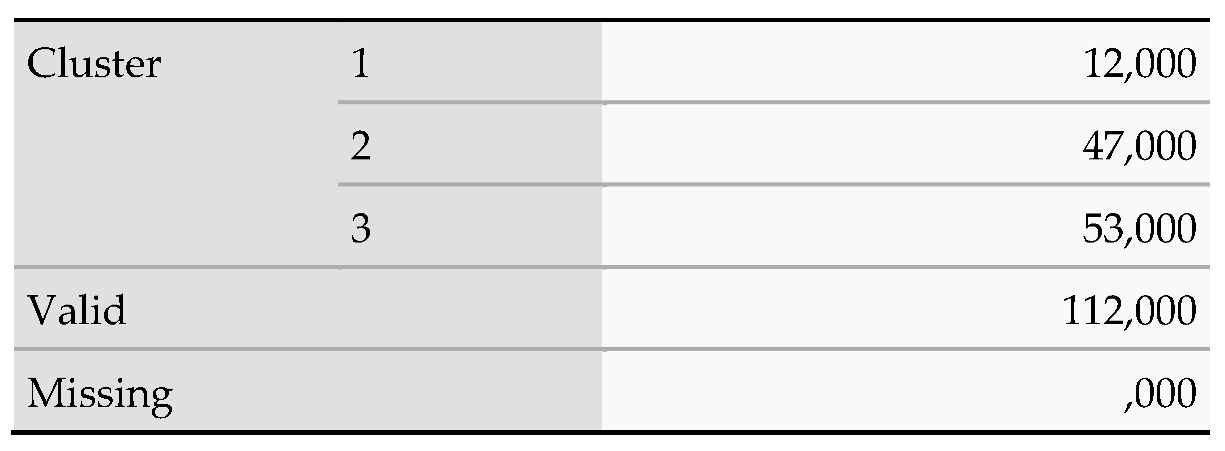

4.2. Organizational Readiness Segment Identification with Multivariate Statistical Analysis

4.2.1. Cluster Profiling with External Variables

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Ward Analysis Dendrogram in grouping hotels’ readiness to integrate local agri-food products in their menus

Appendix B: Iteration History

Appendix C: Number of Cases in each Cluster (k-means cluster analysis)

References

- Anderson, W. Linkages between tourism and agriculture for inclusive development in Tanzania: A value chain perspective. Journal of hospitality and tourism insights 2018, 1(2), 168-184. [CrossRef]

- Bondzi-Simpson, A.; Ayeh, J. Assessing hotel readiness to offer local cuisines: a clustering approach. International journal of contemporary hospitality management 2019, 31(2), 998-1020. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Report on a scoping mission to Samoa and Tonga agriculture and tourism linkages in Pacific island countries, 2012. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/an476e/an476e.pdf (accessed 20.05.2020).

- Madaleno, A.; Eusebio, C.; Varum, C. The promotion of local agro-food products through tourism: a segmentation analysis. Current issues in tourism 2019, 22(6), 643-663. [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.; Momsen, J. Tourism and agriculture: new geographies of consumption, production, and rural restructuring; Routledge: Abington Oxon, 2011. ISBN: 978-0-415-58429-6.

- Vourdoubas, J. The Nexus Between Agriculture and Tourism on the Island of Crete. Greece Journal of Agricultural Studies 2020, 8(2), 393-406. [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, O.; Yilmaz, G. (2016). Gastronomy and tourism. In Global Issues and Trends in Tourism; Avcikurt, C., Dinu, M., Hacioglu, N. Efe, R., Soukan, A, Tetik, N., Eds.; St. Kliment Ohridski University Press: Sofia, 2016; pp. 33-50. ISBN 978-954-07-4138-3.

- Karamustafa, K.; Ülker, M. Chefs’ intentions to use local food: its relation with local food qualities and chefs’ local food familiarisations. Proceedings of 4th International Congress of Tourism & Management Researches, Gyraine, Northern Cyprus, 12-14 May 2017; 2017; 1; pp. 752-768, ISBN: 978-605-65701-6-2.

- UNWTO. Affiliate members global report; Global report on food tourism 2012, 4. [CrossRef]

- Ball, E. Greek Food After Mousaka: Cookbooks, ‘Local Culture, and the Cretan Diet. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 2003, 21(1), 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Damer, S. Legless in Sfakia: Drinking and Social Practice in Western Crete. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 1988, 6(2), 291-310. [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D.; Belhassen, Y.; Shani, A. What makes a gastronomic destination attractive? Evidence from the Israeli Negev. Tourism Management 2013, 36, 200-209. [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Food, place, and authenticity: local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2009, 17(3), 321-336. [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzidakis, D. The pursuit of excellence in Food & Beverage through the use of local products in Grecotel Resorts Hotel in Rethymno. In Crete: Challenges and Opportunities in a 35-year journey. In Tourman 2018 Conference Proceedings, Rhodes, Greece, 25-28 October 2018; Christou, A., Alexandris, K., Fotiadis, A. Eds.; 2018; pp. 546-549. ISBN: 978-960-287-159-1.

- Ji, M.; Wong, I.; Eves, A.; Scarles, C. Food-related personality traits and the moderating role of novelty-seeking in food satisfaction and travel outcomes. Tourism Management 2016, 57, 387-396. [CrossRef]

- Giazitzi, K.; Palisidis, G.; Boskou, G.; Costarelli, V. Traditional Greek vs conventional hotel breakfast: a nutritional comparison. Nutrition & Food Science 2019, 50(4), 711-723. [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.; Yousaf, Z.; Usman, M.; Yousaf, S. Towards Strategic Business Performance of the hospitality sector: nexus of ICT, E-marketing, and organizational readiness. Sustainability 2020, 12(4), 1346. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Cvelbar, L.; Edwards, D.; Mihalic, T. Fashioning a destination tourism future: the case of Slovenia. Tourism Management 2012, 33(2), 305-316. [CrossRef]

- Hinson, R.; Boateng, R. Perceived Benefits and Management Commitment to E-Business Usage in Selected Ghanaian Tourism Firms. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries 2007, 31(1), 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Lehman, W.; Greener, J.; Simpson, D. Assessing organizational readiness for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2002, 22(4), pp. 197-209. [CrossRef]

- Nilashi, M.; Samad, S.; Manaf, A.; Ahmadi, H.; Rashid, T.; Munshi, A.; . . Ahmed, O. Factors influencing medical tourism adoption in Malaysia: a DEMATEL-Fuzzy TOPSIS approach. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2019, 137, 106005. [CrossRef]

- Rousaki, B.; Alcott, P. Exploring the crisis readiness perceptions. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2006, 7(1), 27-38. [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.; Hord, S. Implementing Change: Patterns, Principles, and Potholes, 4th Ed.; Pierson’s Publications: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2015.

- Arica, R.; Çalışkan, C.; & Kodal, S. Organizational change and sectoral transformation: tourism perspective. In Current Debates in Tourism & Development Studies, 1st ed.; S.Dilek, S., Dursun, G., Eds.; London: Ijopec Publication, 2018, Vol. 17, pp. 13-30. ISBN: 978-1-912503-29-2.

- Georgopoulos, A. Human Factors and Organizational Conflict Management in Reorganization. In Reorganization and change management in business; Kallipos, Open academic publications: Athens, Greece, 2015; pp. 171-197. http://hdl.handle.net/11419/1647.

- Laloumis, D. Tourism Business Management; Kallipos, Open academic publications: Athens, Greece, 2015. ISBN: 978-960-603-007-9. http://hdl.handle.net/11419/5283.

- Laloumis, D. (2015). Human Resources Management in Tourism Enterprises; Kallipos, Open academic publications: Athens, Greece, 2015. ISBN: 978-960-603-008-6. http://hdl.handle.net/11419/5295.

- Thomas-Francois, K; Von Massow, M.; Joppe, M. Strengthening farmer-hotel supply chain relationships: a service management approach. Tourism planning & development 2016, 14(2), 198-219. [CrossRef]

- Torres, R. Linkages Between Tourism and Agriculture in Mexico. Annals of Tourism Research 2003, 30(3), 546-566. [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Guidelines for the Development of Gastronomy Tourism; UNWTO & Basque Culinary Center: 2019. ISBN: 978-92-844-2094-0. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284420957 ISBN: 978-92-844-2094-0.

- Gordin, V.; Trabskaya, J.; Zelenskaya, E. The role of hotel restaurants in gastronomic place branding. International Journal of culture, tourism and hospitality research 2016, 10(1), pp. 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Vassiliou, M.; Manitsa, K.; Tsakopoulou, K. Gastronomic tourism: Greek flavors and local development; Theophrastos Digital Library: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Geology, 2015.

- Enterprise Greece. Region of Eastern Macedonia-Thrace Investment Profile, 2017. Available online: https://www.enterprisegreece.gov.gr/images/public/synergassia/Synergasia_2017_Profile_Eastern_Macedonia-Thrace_final.pdf (accessed 07.01.2021).

- Hellenic Chamber of Hotels. Hotel Potential of the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, 2019. Available online: https://www.grhotels.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2019-Campings_regions.pdf (accessed 09.10.2020).

- Pavlidis, G.; Markantonatou, S. Gastronomic tourism in Greece and beyond a thorough review. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 2020, 21, 100229. [CrossRef]

- REMTH. Regional Operational Programme of Eastern Macedonia - Thrace 2014-2020, Special Service for the Management of OP REMTH. Available online: https://www.eydamth.gr/index.php/extras/to-programma (accessed 14.07.2020).

- REMTH. Strategic and Operational Plan for Tourism Development of the Region of EMTH, Special Management Service of the REMTH Regional Development Programme. Available online: https://www.eydamth.gr/lib/articles/newsite/ArticleID_657/sxedio_tourist_anapt_AMTH.pdf (accessed 18.10.2020).

- Demofelia of Kavala. Communication Policy - Tourism Promotion Plan of the Municipality of Kavala, 2019. Available online: http://www.kavalagreece.gr/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/parartima-5-sxedio-draseon-touristikis-probolis.pdf (accessed 05.01.2021).

- Hellenic Chamber of Hotels. Detailed Hotel Search. Available online: https://services.grhotels.gr/el/searchaccomodation/ (accessed 09.10.2020).

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Zafeiropoulos, K. How is a scientific paper done? Scientific research and paper writing, 2nd ed.; Kritiki S.A.: Athens, 2015. ISBN 978-960-586-077-6.

- Christodoulides, G.; Michaelidou, N.; Siamagka, T. A typology of internet users based on comparative affective states: evidence from eight countries. European Journal of Marketing 2013, 47(1/2), 153-173. [CrossRef]

- Kyrkos, E. Cluster analysis. In Business Intelligence and Mining; Kallipos, Open academic publications: Athens, Greece, 2015; pp. 261-281. http://hdl.handle.net/11419/1238.

- Petridis, D. Cluster analysis. In Analysis of multivariate techniques; Kallipos, Open academic publications: Athens, Greece, 2015; pp. 158-193. http://hdl.handle.net/11419/2126.

- Adongo, C.; Anuga, S.; Daynour, F. Will they tell others to taste? International tourists’ experience of Ghanaian cuisines. Tourism Management Perspectives 2015, 15, 57-64. [CrossRef]

- Seyitoglu, F. Components of the menu planning process: the case of five-star hotels in Antalya. British Food Journal 2017, 119 (7), 1562-1577. [CrossRef]

- Iloranta, R. Luxury tourism – a review of the literature. European Journal of Tourism Research 2021, 30, 3007. [CrossRef]

- Batat, W.; Peter, P.C.; Moscato, E.M.; Castro, I.A.; Chan, S.; Chugani, S.; Muldrow, A. The experiential pleasure of food: A savoring journey to food well-being. Journal of Business Research 2019, 100, 392-399. [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Gastronomy: an essential ingredient in tourism production and consumption. In Tourism and Gastronomy; Hjalager, A.M., Richards, G, Eds.; Routledge: London, NY, 2002; pp. 3-20. ISBN 0-203-27406-7.

- Kafatos, A.; Verhagen, H.; Moschandreas, J.; Apostolaki, I.; Van Westerop, J. Mediteranian diet of Crete: foods and nutrient content. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2000, 100(12), 1487-1493. [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulou, E.; Trichopoulou, A. Green pies: the flavonoid-rich Greek snack. Food Chemistry 2011, 126, 855-858. [CrossRef]

- Zoidou, E.; Melliou, E.; Gikas, E.; Tsarbopoulos, A.; Magiatis, P.; Skaltsounis, A. Identification of Throuba Thassos, a Traditional Greek Table Olive Variety, as a Nutritional Rich Source of Oleuropein. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2010, 58(1), 46-50. [CrossRef]

- Panagou, E.; Nychas, G.; Sofos, J. Types of traditional Greek foods and their safety. Food Control 2013, 29(1), 32-41. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Mediterranean diet. Cyprus, Croatia, Spain, Greece, Italy, Morocco and Portugal. Inscribed in 2013 (8. COM) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884 (accessed 18.10.2020).

- Reynolds, D.; Merritt, E.A.; Pinckney, S. Understanding menu psychology: An empirical investigation of menu design and customer response. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration 2005, 6(1), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, S.; Dawson, M.; Johnson, W. How to increase menu prices without alienating your customers. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2005, 17(7), 553-568. [CrossRef]

- Ginigen, D.; Aydın, B.; & Güçlü, C. Local food availability in menus of hotels: The case of Batman, Turkey. Journal of Mediterranean Tourism Research 2022, 1(2), 81-99. https://www.doi.org/10.5038/2770-7555.1.2.1007.

- Baiomy, A.E.; Jones, E.; Goode, M.H. The influence of menu design, menu item descriptions, and menu variety on customer satisfaction. A case study of Egypt. Tourism and Hospitality Research 2019, 19(2), 213–224. [CrossRef]

- Duram, L.A.; Cawley, M. Irish Chefs and Restaurants in the Geography of “Local” Food Value Chains. The Open Geography Journal 2012, 5, 16-25. doi: 10.2174/1874923201205010016.

- Davis, B.; Lockwood, A.; Pantelidis, I.; Alcott, P. Food and Beverage Management, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008. ISBN 13: 978-0-7506-6730-2.

- Frei, B.T. The menu is a money maker. Restaurants and Institutions 1995, 105(6), 144-145.

- Mills, J.E.; Thomas, L. Assessing Customer Expectations of Information Provided On Restaurant Menus: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis Approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2008, 32(1), 62 - 88. [CrossRef]

- McVety, P.J.; Ware, B.J.; Ware, C.L. Fundamentals of menu planning, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, USA, 2008. ISBN: 978-0-470-07267-7.

- WFTA. State of the Food Travel Industry Report. World Food Travel Association: 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Roberta-Garibaldi-2/publication/343255792_2020_State_of_the_Food_Travel_Industry_Report/links/5f20037d299bf1720d6ac9c3/2020-State-of-the-Food-Travel-Industry-Report.pdf (accessed 14.07.2021).

- UNWTO. Annual Report; World Tourism Organization, 2017. ISBN: 978-92-844-1980-7.

- Yeoman, I. Tomorrow’s Tourist: Scenarios & Trends; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2008. ISBN 978-0-08-045339-2.

- SETE. Gastronomy in the Marketing of Greek Tourism. Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises, 2009. Available online: https://sete.gr/_fileuploads/gastro_files/100222gastronomy_f.pdf (accessed 20.05.2020).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

| Ν | % | ||

| Area | Thassos | 87 | 78 |

| Kavala | 25 | 22 | |

| Age of the hotel | 32+ years old | 17 | 15 |

| 16 -31 years old | 67 | 60 | |

| <15 years old | 28 | 25 | |

| Hotel category (stars) | 1* | 9 | 8 |

| 2* | 39 | 35 | |

| 3* | 36 | 32 | |

| 4* | 19 | 17 | |

| 5* | 9 | 8 | |

| Hotel capacity (rooms) | 1-20 rooms (very small) | 28 | 25 |

| 21-50 (small) | 58 | 52 | |

| 51-100 (medium size) | 17 | 15 | |

| ≥101 (large) | 9 | 8 | |

| Hotel opening period | Seasonal | 89 | 79,5 |

| All year round | 23 | 20,5 | |

| Nationality of customers | Foreigners | 95 | 85 |

| Greeks | 17 | 15 | |

| Meals | Breakfast | 111 | 99 |

| Lunch | 58 | 52 | |

| Dinner | 74 | 66 | |

| Meal Service Mode | All-inclusive | 8 | 7 |

| Buffet | 88 | 79 | |

| a la carte | 69 | 62 | |

| The food service manager at the hotel | Owner/Director | 92 | 82 |

| Chief | 14 | 12 | |

| F& B Manager | 4 | 4 | |

| Procurement Officer | 2 | 2 | |

| The locality of the Chef of the hotel | Local | 50 | 45 |

| Non-permanent resident | 32 | 29 | |

| Permanent resident | 15 | 13 | |

| Unknown locality | 15 | 13 |

| Hotel readiness indicators * | Cluster Ι Indifferent (Ν=12) |

Cluster ΙΙ Hesitant (Ν=47) |

Cluster ΙΙΙ Committed (Ν=53) |

ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD** | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F | Sig | |

| Organisational Culture | ||||||||

| Satisfactorily serves the hotel’s target clientele | 2,17 | 0,72 | 3,87 | 0,54 | 4,79 | 0,41 | 143,33 | 0,001 |

| Fits the hotel’s image | 2,17 | 0,72 | 3,89 | 0,38 | 4,77 | 0,42 | 180,24 | 0,001 |

| It coincides with the hotel’s vision and mission | 2,08 | 0,67 | 3,83 | 0,56 | 4,75 | 0,48 | 130,16 | 0,001 |

| It fits with the marketing strategy of the hotel | 2,00 | 0,60 | 3,85 | 0,55 | 4,70 | 0,58 | 115,67 | 0,001 |

| Organizational Climate | ||||||||

| Food service managers can persuade staff to use and promote them | 2,75 | 0,87 | 3,79 | 0,83 | 4,77 | 0,42 | 55,50 | 0,001 |

| The staff is willing to learn how to use them in the menu recipes | 2,75 | 0,75 | 3,74 | 0,44 | 4,62 | 0,53 | 77,30 | 0,001 |

| The staff is willing to show them from the menu list | 2,67 | 0,78 | 3,64 | 0,53 | 4,60 | 0,53 | 74,58 | 0,001 |

| Organizational Capacity | ||||||||

| The appropriate infrastructure and equipment | 2,58 | 1,00 | 3,74 | 0,61 | 4,49 | 0,67 | 42,47 | 0,001 |

| The necessary networks of partners and suppliers | 2,42 | 0,67 | 3,60 | 0,77 | 4,43 | 0,57 | 50,61 | 0,001 |

| The necessary human resources | 2,00 | 0,74 | 3,34 | 0,70 | 4,53 | 0,61 | 87,56 | 0,001 |

| The financial resources required | 1,58 | 0,67 | 3,23 | 0,76 | 4,19 | 0,74 | 66,49 | 0,001 |

| Notes: *Measured on a 5-point scale (1) Strongly disagree - (5) Strongly agree; **Standard Deviation | ||||||||

| Variable | Cluster membership | chi-square test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (%) | II (%) | III (%) | ||

| Hotel category (stars) | ||||

| 1* | 33,3 | 2 | 8 | p=0.001 |

| 2* | 58,3 | 45 | 21 | |

| 3* | 8,3 | 41 | 30 | |

| 4* | - | 6 | 30 | |

| 5* | - | 6 | 11 | |

| Breakfast | 92 | 100 | 100 | p=0.015 |

| Lunch | - | 53 | 66 | p=0.001 |

| Dinner | 17 | 62 | 77 | p=0.001 |

| Offer a la carte meals in a restaurant | 25 | 36 | 68 | p=0.020 |

| The locality of the Chef | ||||

| Local | 58,3 | 32 | 53 | p=0.039 |

| Permanent resident | 8,3 | 17 | 11 | |

| Non-Permanent resident | - | 36 | 28 | |

| Unknown Locality | 33,3 | 15 | 8 | |

| Perceived benefits indicators * | Cluster | N | Mean | SD** | Wellch’s F | Post hoc test (Games-Howell) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | Clusters | Sig. | |||||

| Enhances the nutritional value of menus | I | 12 | 3,33 | 0,65 | 36,69 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.015 |

| II | 47 | 4,00 | 0,66 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 4,72 | 0,46 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| Contributes to the positive image and prestige of the hotel | I | 12 | 3,00 | 1,13 | 29,74 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.040 |

| II | 47 | 3,94 | 0,57 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 4,66 | 0,52 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| Shapes culinary experiences for customers | I | 12 | 3,00 | 0,85 | 27,55 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.003 |

| II | 47 | 4,09 | 0,65 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 4,64 | 0,48 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| It gives staff a sense of pride in their “local” identity | I | 12 | 2,75 | 1,06 | 24,99 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.013 |

| II | 47 | 3,83 | 0,84 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 4,60 | 0,66 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| Improves the demand (attractiveness) for menus | I | 12 | 2,83 | 0,94 | 32,18 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.016 |

| II | 47 | 3,77 | 0,79 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 4,60 | 0,57 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| Offers the hotel a competitive advantage | I | 12 | 2,92 | 0,67 | 30,82 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.004 |

| II | 47 | 3,77 | 0,84 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 4,51 | 0,70 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| Helps to increase the repeatability of hotel guests (Repeaters) | I | 12 | 2,42 | 0,80 | 18,96 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.002 |

| II | 47 | 3,49 | 0,78 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 4,06 | 0,99 | II & III | 0.005 | |||

| Facilitates access to raw materials for menus (short transport distance) | I | 12 | 1,92 | 1,08 | 21,76 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.002 |

| II | 47 | 3,32 | 0,94 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 3,96 | 0,78 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| Reduces the prices of menus | I | 12 | 1,33 | 0,65 | 17,93 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.001 |

| II | 47 | 2,40 | 0,85 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 2,68 | 0,89 | II & III | 0.261 | |||

| Reduces the cost of menu production | I | 12 | 1,50 | 0,91 | 7,93 | 0,002 | I & II | 0.010 |

| II | 47 | 2,49 | 0,93 | I & III | 0.003 | |||

| III | 53 | 2,66 | 0,90 | II & III | 0.621 | |||

| Notes: *Measured on a 5-point scale (1) Strongly disagree - (5) Strongly agree; **Standard Deviation | ||||||||

| Variable* Intention |

Cluster | N | Mean | SD** | Wellch’s F | Post Hoc Test (Games-Howell) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | Clusters | Sig. | |||||

| The hotel’s intention to include (more) local products on the menus | I | 12 | 1,75 | 0,75 | 46,55 | 0,001 | I & II | 0.001 |

| II | 47 | 3,06 | 0,75 | I & III | 0.001 | |||

| III | 53 | 3,75 | 0,43 | II & III | 0.001 | |||

| Notes: *Measured with (1) I have no intention of...; (2) Sometime in the future (after 5 years); (3) In the coming years (2-5 years); (4) Immediately (this year); **Standard Deviation | ||||||||

| Hotel intention | Cluster membership | chi-square test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (%) | II (%) | III (%) | ||

| Immediately (this year) | 32 | 75 | p=0.001 | |

| In the coming years (2-5 years) | 16,7 | 49 | 25 | |

| Sometime in the future (after 5 years) | 41,7 | 13 | ||

| I have no intention of... | 41,7 | 6 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).