1. Introduction

Accountability is a concept that finds wide but varied use, with a degree of consensus existing among scholars and professionals when it comes to its meaning in the context of social interactions, transactions, documented research, and informed commentary. However, the core of public accountability remains elusive and fragmented. Theories and models of governance, such as the principal-agent theory, legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory, and new public management (NPM), offer insights into accountability, primarily focusing on aspects like account-giving, answerability, agency dilemmas, societal norms and values, stakeholder interests, and efficiency (Freeman, 1984; Stewart, 1984; Guthrie & Parker, 1989; Bovens, 1998; Chan, 2006; Ahmad, 2016)

Experts have made an enormous investment of effort to articulate the definition and dimensions of public accountability and designs of mechanisms for operationalising the concept in the public sector. However, not much is documented about the effort to probe into and establish the ultimate purpose of public financial accountability. The literature is definite that accountability is an established aim of financial reporting in the public-sector (GASB, 1987, 1999; FASAB, 2012; IPSASB, 2015).

The study argues an effective way to understand and address a social phenomenon is to pay special attention to the essence (the underlying meaning) or what it represents rather than its semantic meaning or definition. Within the governance frame, public accountability is commonly understood as the obligation on public entities to render an account of their activities, through their officials, to the public by explaining and justifying key policies, decisions and actions (Gray & Jenkins, 1993; Bovens, 1998; Desai, 2009; Cendon, 2011; Akponuko & Asogwa, 2013; Mansbridge, 2014; Stapenhurst & O’Brien, 2015; CIPFA, 2018). Also, financial reporting is understood as the foremost mechanism for discharging financial accountability (Coy et al., 2001; Samkin & Schneider, 2010; PwC, 2013).

The meaning of public accountability given above is semantic because it fails to convey a mental construct of the purpose of account-rendering that can form a thematic fulcrum for accountability discourses and mechanisms. Unfortunately, literary texts in accounting and financial reporting seem to focus on the literal meaning of accountability. In contrast, a better apprehension of the ultimate nature of public accountability is required to design frameworks and mechanisms for discussing and addressing contemporary financial accountability challenges in the public sector. Therefore, there is a need for a systematic insight into the intrinsic or permanent purpose (the essence) of public accountability to avoid “losing sight of the forest for the trees” (Thomson, 2015). There is also a need to examine how the findings of such an investigation could be applied in public-sector financial reporting to reflect country-specific contextual realities.

This study was designed to answer a two-pronged question: What is the ultimate purpose of public financial accountability, and how can this purpose be realised through financial reporting? The research agrees with prior studies (Premchand, 2001; Coy et al., 2001; Hooks et al., 2012; Heiling et al., 2013) that there are information gaps in conventional financial reports. However, argues that the ineffectiveness of public-sector financial reporting in demonstrating an acceptable measure of accountability in many districts could be due to a poor understanding of the real essence of public accountability by preparers of financial reports.

Nigeria provides an excellent setting to conduct this investigation being one of the developing countries often reported as experiencing severe financial accountability challenges manifesting in monumental public corruption (Transparency International, 2018). Prior studies reveal that financial reports published by public entities in the country do not meet the accountability needs of users (Arua, 2003, 2005; Akhidime, 2011; Omolehinwa, 2014; Mande, 2015).

The study is organised into three sections. Section one is the background of the study and a review/discussion of some scholarships and professional viewpoints related to the notion and characterisations of public accountability and the practice of financial reporting in the public sector. The review and discussion aim to highlight existing knowledge on the research topic and the significance of the current effort. The method to collect and analyse data is explained in section two. The study was conducted from citizens’ perspectives on the premise that public perception determines the state of public accountability. Key findings are discussed in section three, and the concluding section includes policy implications.

2. Literature Review

The ability of public finance managers and accounting professionals to meet the increasing demands for accountability through financial reporting is becoming a global challenge. Many democratic governments prepare and publish their audited financial statements annually in compliance with existing laws, regulations and standards, with some public entities in Western countries publishing quarterly and semi-annual financial reports (PwC, 2013). However, public financial accountability remains unsatisfactory globally, particularly among the developing nations of Africa, Asia and Latin America (World Bank, 2004). Dubnick & Frederickson (2010, p. 43) describe the situation as “the public administration challenge of our time”.

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2017, published by Transparency International, corroborates these observations, reporting that more than two-thirds of the 180 countries surveyed have a serious corruption problem, scoring less than 50 points on a 100-point scale. The report further reveals that Central Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Europe are the regions performing worst. Corruption perception improved marginally in 2017 across Europe and Central Asia compared to published figures for assessment periods in 2015 and 2016, with a more substantial number of countries in Africa experiencing a rise in public corruption with varying dimensions and proportions (Transparency International, 2018).

When public resources are mismanaged or misappropriated through corrupt practices or other forms of financial impropriety, the inevitable consequences are limited social variance and services, inequality, and 'artificial poverty' (caused by resources poor management). In recent times, extreme violent behaviours and even aspects of terrorism have been traced to frustration arising from poor public financial management and corruption (Proulx, 2012).

Global concern and domestic anxiety about poverty and insecurity are propounded as the core reasons behind the growing demand, by citizens and other stakeholders, for improved public financial accountability as a means of controlling corrupt practices and misappropriation of public resources. This concern further challenges policymakers, standard setters, and accounting professionals to regularly assess the adequacy and effectiveness of vital institutional mechanisms for ensuring financial accountability in the public sector.

There are two principal purposes of public-sector financial reporting: accountability and decision-making (IPSASB, 2015), and previous studies have revealed that the public is concerned more about accountability than decision-making1 (Mack, 2003; GASB 1987, pars. 56, 76). Indeed, GASB (1987) clearly says that accountability must act as the foundation of all other financial reporting objectives. The system of general-purpose financial reporting is globally accepted as the foremost mechanism for demonstrating financial accountability in the public sector (Cordery & Simpkins, 2016).

The tenet of the 'Citizens' Right to Know' entitles the public to information about the following critical areas of public financial management:

How public funds are raised

How public funds are used

What are available public goods and services

The efficiency and efficacy in achieving the goals of public administration.

Statutes and conventions oblige public officials to provide this information regularly for stakeholders openly: - citizens, elected officials, civil society organisations, lenders, creditors, development partners to entitle them to assess and determine the financial operations of the government (GASB, 1987, p. 28). Public accountability is imperative because governments in all democratic arrangements derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, giving them an obligation not only to exercise these powers appropriately but also to report on their actions and subsequent results (FASAB, 2012). In other words, the exercise of governmental powers is made legitimate by the requirement that those who exercise government power must be publicly accountable for their actions (Stewart, 1984).

Although financial reporting is neither the sole source of financial particulars about a public entity nor the only means of achieving accountability in government (Coy et al., 2001; Patton, 2001; FASAB, 2012), it is regarded as a principal component of public financial management, and an indispensable accountability mechanism (PwC, 2013). There are also claims that financial reports represent the icon, hallmark, cornerstone and the best index of accountability because they translate abstract thought about accountability into the domain of reality (Arua, 2003; Rixon, 2007; Chahed, 2009; Samkin & Schneider, 2010). In fact, Coy et al. (2001) are emphatic that a financial report is the only document that provides comprehensive information about financial and non-financial terms of an organisation's objectives and performance.

The mismatch between financial reporting and public accountability continues to stir up discussions that interrogate the significance of general-purpose financial reporting in the public sector and, by extension, the relevance of public-sector financial accountants to the broader society. However, the positive relationship described above between financial reporting and public accountability in many developing countries is only notional. A common belief or perception in many countries is that public accountability is poor (in extreme cases, non-existent) despite the practice of routine financial reporting (Steccolini, 2004; Chatterjee et al., 2010; Hooks et al., 2012).

Premchand (2001, p. 14) summarises this standpoint succinctly as follows:

"The overwhelming impression about the information released by governments on their financial transactions and associated transparency arrangements is that there are vital gaps in it, and it is far from adequate in serving the interests of the public. Budgets and accounts in government-speak a technical language that tends to be extremely difficult for the public to comprehend".

Also, Normanton (1971, quoted in Coy et al., 2001, p. 24) describes the inadequacy of financial statements for accountability purposes in the following strong remarks:

"It is not accountability merely to submit a certified financial account each year. To be accountable means to give reasons for, and explanations of, actions are taken; but an account rarely provides explanations, and it never gives reasons".

Evident in the above references is a strong perception of a discrepancy between the presumption of the public and the information provided by the financial reports of governments. Given the positive and interwoven relationships between financial reporting, public accountability and good governance (Romzek, 2015), the effectiveness of financial reporting in promoting the culture of financial accountability in the public sector would be enhanced. However, the report preparers must clearly understand the essence of financial accountability and that the core of their responsibility is to realise this essence rather than merely producing accounting information about financial transactions and conditions of public entities.

3. Meaning and Perspectives of Public Accountability

Although there seems to be no universal definition of accountability (UN, 2001; Mack, 2003; Bovens et al., 2014) because of its evocative powers that makes it elusive despite its extensive application (GASB, 1987; Bovens, 1998, 2005, 2006), there is reasonable consensus among scholars and professionals on the meaning of public accountability. Public accountability is commonly understood as the responsibility of the public office-holders to be answerable to the public by explaining and justifying their decisions and actions in running the affairs of public entities. This viewpoint is in consonance with the traditional definitions found in the literature (see Ackerman, 2005; Cendon, 2011; Mansbridge, 2014; Stapenhurst & O’Brien, 2015; CIPFA, 2018), which confine the concept of accountability to the fiduciary responsibility of one party in the social contract, namely, the government, its agencies and officials.

A more comprehensive meaning is provided in the accountability models that think of public accountability as a connection linking the government and the people in which the people also have a civic duty to hold the government to account by assessing and judging its performance and enforcing sanctions and rewards as applicable (Stewart, 1984; Gray & Jenkins, 1993; Bovens, 1998; Chan, 2006; Desai, 2009; Akponuko & Asogwa, 2013; Vance et al., 2015). The people entrust unto the government (national, regional, state or local) and their agencies with the responsibility to manage their common economic resources to supply public goods and services and report to the people on the way it has carried out this responsibility.

The accountability connection among the government and the people derives from the general contract theory. It forms the focus of the principal-agent model within the public-sector environment in which the government is the agent, and the people are the principal. Bovens (1998, p. 7) refers to this relationship as "between the actor and the forum in which the actor has an obligation to explain and justify his or her conduct. The forum can pose questions and pass judgement the actor can be sanctioned". Chan (1992) describes the forum as the citizen groups, while IPSASB (2015) prefers 'resource providers and service recipients’. Desai (2009, p. 7) refers to the two parties as ‘Rights Holders’ (the public) and ‘Duty Bearers’ (the government). The people claim their rights while the government fulfils its obligations.

Stewart (1984) mentions the responsibility to explain and justify decisions and actions as ‘account-rendering’ and the duty of the citizen groups and oversight institutions to assess, judge and sanction as ‘holding to account’. Stewart (1984) stresses that the account rendered by the government forms the basis for holding it to account, implying that public accountability is a justification of the competence of principals to determine the performance of their agents. Therefore, it is imperative that the account rendered by the agent provides information that enables the principal to hold it to account.

With respect to the obligation of the citizenry in the accountability process, Akpanuko & Asogwa (2013) argue that ‘holding-to-account’ is, at least, as important as ‘account-rendering’. Also, Asechemie, 1995, cited in Akpanuko & Asogwa, (2013) contend that accountability is related to the right to question; that intuitively, the accountability would only exist if the public officials anticipated questions within and after their generalship to the society. Bovens (2006) also argues that accountability is beyond a monologue; accountability is not propaganda or mere information but must provide a mechanism for debate and engagement. The sanction comes after the principal has exercised his power to judge the actions or conduct of the agent and passed an adverse judgement.

Holding-to-account is important because a relationship in which there is no form of control based on reward or sanction cannot be described as an accountability relationship (Smyth 2004). Accountability holds the promise of generating desired performance and bringing someone to justice (Dubnick & Romzek, 1991). As Schillemans & Busuioc (2014) observe, it is not only the problem of drifting agents that is important to address terminology of accountability, but also the state of drifting principals and forums, which surprisingly prefer to ignore the wrong doings of their agents and mysteriously do not pay attention to their actions.

Premchand (2001) stretches the argument further stressing importance of providing transparent fiscal information on the financial activities of governments, either to a specific group; for instance, the legislature or to other relevant groups, is a way to, and not an alternate to accountability; that the presence of a body of oversight charged with the authority of evaluating the information provided and reporting on that to the public is the core element in accountability. However, Egbon (2014) canvassed a different standpoint contending that accountability is driven by the right to know rather than the use of the information. This opinion suggests that citizens are more concerned with account-rendering by the government than with their civic duty to hold public offers to account.

Examined from the principal-agent model of public accountability, the core sense of accountability relates to the process of being called ‘to account’ to some authority for one’s actions (Jones, 1992, p. 73, cited in Mulgan, 2000). Such accountability has several characteristics: (1) it is external, in that case the account is handed over to another person or body outside the person or body being responsible; (2) if it entails social interconnection, in that situation, the side calling for the account, try to find answers and justifications while on the other hand the side being held accountable, answers and accepts penalties; (3) it infers rights of authority, in that case those asking to justify are exercising rights of superior authority over those who are accountable (Mulgan, 2000) or to reward adequate performance (Bovens et al., 2014).

As FASAB (2012) expatiates, governments in all democratic arrangements derive their just powers from the consent of the governed; therefore, they have a special obligation to exercise these powers appropriately and report on their and the results of those actions. Thus, public accountability is unarguably an essential condition for the democratic process. "It is a golden concept that no one can be against" (Bovens, 2006, p. 5). Nonetheless, Romzek (2015) draws attention to the fundamental vagueness associated with the concept of accountability. She explains that accountability is taking responsibility for performing appropriately, which, if it is working correctly, should result in a reward or a penalty. She further contends that, across districts, accountability remains a hot rhetoric, an excellent theory but uneven practice. In other words, accountability is not felt in practice as it is discussed in theory.

Accountability mechanism consists of policies or institutions through which public officials can be held accountable (Desai, 2009). It involves institutional arrangements or relationships in which an individual or body, and the performance of tasks or functions by that individual or body, are subject to another’s oversight, direction or request that they provide information or justification for their actions. In this sense, accountability is the answerability for one’s action and behaviour, and the right to be questioned, defined by the relationship of responsibility, obligation and duty (Akpanuko & Asogwa, 2013, p. 166). These views corroborate the emphasis on justifying actions and conduct and the need for sanctions or punishment in Bovens et al. (2014) but further expound the significance of sanctions or punishment.

Several dimensions, forms or characterizations of public accountability have been suggested in the literature. These forms can be broadly classified into two, namely, horizontal accountability and vertical accountability. The literature is divided into the explanation or description of each dimension. Some scholars define horizontal accountability in the public sector as the patterns of accountability relationships between governments and the legislatures and the public, and vertical accountability as the accountability of the lower levels to the higher levels within an organisation (Premchand, 2001; Khan, 2006). It suggests that horizontal accountability is to external stakeholders, while vertical accountability is an internal relationship.

Other literary texts (Cendon, 2011; Transparency and Accountability Initiatives, 2017) hold divergent opinions. For example, Transparency and Accountability Initiatives (2017) describes horizontal accountability as the requirement for autonomous powers or institutions of government to report sideways to check abuses in the discharge of public responsibilities (internal relationships within the government). Transparency and Accountability Initiatives (2017) also explains that vertical or external accountability is the obligation of public entities and their officials to account directly to citizens, mass media and civil society groups to enable them to enforce standards of satisfactory performance on public officials. Cendon (2011) and Lewis et al. (2015) concur but prefer the term 'democratic accountability for the accountability relationship between the government and the citizenry.

Classifications of public accountability include derivatives such as financial (fiduciary or probity) accountability, political or social accountability, performance or outcome accountability, legal accountability, managerial accountability, administrative or process or procedural accountability, ex-ante and post-ante, individual or personal accountability and organisational accountability (Stewart, 1984; Bovens, 1998, 2006; Khan, 2006; Connolly & Dhanani, 2009; Akpanuko & Asogwa, 2013).

This study is primarily connected with accountability by governments to the public managing public financial resources. Therefore, of all the dimensions and classifications of accountability discussed in the preceding paragraphs, public accountability's financial and external perspectives relate to the study.

4. Financial Reporting as an Instrument of Accountability

Many abstract concepts are demonstrated employing practical mechanisms. For example, kindness is an abstract concept demonstrated through philanthropy. Accountability is one of such abstractions, and general-purpose financial reporting is the foremost mechanism for demonstrating the concept (Cordery & Simpkins, 2016). According to Chahed (2009), a financial report translates abstract thought about accountability into the domain of reality. Financial reports are the only documents that provide comprehensive accountability information for citizens (Rayegan et al., 2012; Coy et al., 2001). The reports provide information on government revenue, expenditure and financial position (among other reports) in each period for the benefits of both external stakeholders. Thus, financial reports can be described as the lens through which financial accountability can be viewed or the scale for measuring accountability. As Regan et al. (2012 p. 528) emphasise, "It is not enough to keep the books accurately; the books have to be open to the public". This statement underscores the difference between financial accounting and financial reporting.

Financial statements refer to financial data and other information generated from the accounting process and presented in highly structured formats. The statements provide information about the financial results (whether described as "surplus or deficit," "profit or loss," or by other terms), cash flows of an entity during the reporting period, its assets and liabilities at the reporting date and the change therein during the reporting period (Rayegan et al., 2012; IPSASB, 2015). In general parlance, the term 'financial reports' is often used interchangeably with financial statements, but technically, there is a margin of difference in meaning.

In contrast, a financial report is a broader concept. It comprises the financial statements (including the notes) and other descriptive information about an entity and its activities (Mack, 2003). Descriptive information (referred to as narrative or supplementary information) may or may not be financial in nature and is meant to complement, supplement and enhance the financial statements (IPSASB 2015). Also, narrative or supplementary information may relate to the data in the financial documents or to facts about the reporting entity that is not in the financial statements but are required by the report users to comprehend the financial statements properly and assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the establishment’s operations covered in the period of reporting, as well as its financial state and prospects (FASAB, 1999; Chahed, 2009). Declaring relevant information is crucial for government or public-sector entities to release accountability commitment to the people, to justify the use of the resources on behalf of constituents (Chan, 2006, IFAC, 2015).

To distinguish external financial reports from internal reports prepared by government officials for management and decision-making, or compliance reports for external regulatory bodies, or from any other form of a report for specific purposes, standard setters (IPSASB, FASAB, GASB, AASB) use the term General Purpose Financial Reports (GPFRs). The term is defined in the literature (IPSASB, 2015, p. 29) as "financial reports intended to meet the information needs of users who are unable to require the preparation of financial reports tailored to meet their specific needs". The potential usage of governmental financial reports is usually so vast that it would be impracticable to prepare reports that meet individual users' requirements, necessitating reports that can meet information needs common to the wider users.

Thus, two categories of fiscal reports exist in the literature: Special Purpose Financial Reports (SPFRs) and GPFRs (IPSASB, 2015, p. 11). As the name implies, SPFRs are reports prepared to meet the specific demands of notable stakeholders (regulatory agencies, Parliament, institutional financiers) who possess the power to command the supply of such reports. This study is concerned with GPFRs, which, as has been explained, typically comprise the Basic Financial Statements (BFSs) or General-Purpose Financial Statements (GPFSs) and relevant information that increases the reliability by complementing the financial statements.

Although the concept and application of general-purpose financial reporting do not diminish the fundamental and indispensable place of financial statements as the core of financial reporting, it remains indisputable that BFSs provide only financial results expressed in accounting language, which only partially provides the accountability information needed by users (Premchand, 2001; Rixon, 2007).

The inadequacy of the BFSs for accountability purposes is the key factor driving the concept and practice of narrative or supplementary reporting as a component of GPFRs in the public sector worldwide. Compared to the business environment, general-purpose financial reporting is a new concept in public sector accounting and fiscal accountability in many districts. Indeed, IPSASB embraced the concept less than a decade ago (in 2008) when it commenced its project on 'The Conceptual Framework for General Purpose Financial Reporting by Public Entities'. Before the board's emphases (as evident in its publications) and of other standard-setters, scholars and practitioners were focused on BFSs.

As citizens become increasingly conscious of and concerned about public decisions and actions that affect their lives, the demand for better explanations regarding the use of their commonwealth grows (Luder, 1992), sometimes leading to agitations that often stoke public disorder and general insecurity. Regular, effective and honest communication between public fiscal managers and the people would reduce the incidence of fund misallocation and its adverse impacts on the lives of the citizens (Martinez-Gonzalez & Marti, 2006).

The primary purpose of a private sector organisation is to generate a commercial return for investors. As a result, the core of accounting in the private sector is determining financial return (profit) over a given period. In contrast, public sector entities exist primarily to provide public goods and services to citizens either free of direct charges or at notional cost (Khan, 2006). Thus, government accounting is undertaken to provide information that explains and justifies how funds are raised and applied in providing such goods and services (ICAN, 2014).

The US Governmental Accounting Standard Board (GASB, 1987) suggests the following as objectives of general purpose financial reporting: (a) Financial reporting(FR) must aid in accomplishing the government's duty to be candidly responsible and must authorise the users to evaluate that accountability; (b) FR must permit users to assess the functional results of the government establishment for the year, and (c) FR must also allow the users to evaluate the level of services that can be provided by the governmental body and its potential to fulfil its responsibility as they become due. IPSASB (2015, p. 13) and IMF (2007) are definite that the core purpose of government FR by a public-sector entity is to supply information related to the entity, helpful to the users for assessing accountability and then utilising for the purposes of appropriate decision-making. Moreover, GASB (1987), Chan (1992, p. 17-18), Mack (2003), Clark (2010, p. 75) are convinced that accountability is more important to the public than decision-making.

On the contrary, the Australian Public-Sector Accounting Standard Board (APSASB) suggests that decision usefulness is the cardinal purpose of government financial reporting. The Board unequivocally states that the purpose of government financial reporting in Australia is decision usefulness, meaning decision-making (Mack, 2003). By the Board's affirmation, the accountability purpose of government financial reporting is not just gravely diminished but obliterated.

5. Data Collection and Analysis

A qualitative research approach was adopted to gather and analyse the perspectives of primary users of public-sector financial reports. Qualitative data was obtained through in-depth interviews conducted with a sample of primary users of public-sector financial reports in Nigeria. These interviews were conducted using a variety of methods, including face-to-face meetings, Skype sessions, and direct phone calls. To ensure accurate representation and comprehension of the information provided, all interviews were audio-recorded.

The primary dataset consisted of transcripts derived from the recorded responses of the interview participants. These responses were obtained through semi-structured questions that explored the concepts of financial accountability and how financial reporting could be tailored to enhance the realization of this accountability within the public sector.

In line with standard qualitative research design principles, collected a substantial volume of non-numerical data from a deliberately selected and relatively small sample (Hox & Boeije, 2005, p. 593). Our purposive sample comprised 25 senior officials drawn from both public and private organizations, encompassing five distinct user categories: Government accountants and auditors, financial consultants, academia, legislators, and public affairs commentators, including representatives from civil society organizations and the media. The distribution of interview participants among these categories is presented in

Table 1.

The sample included both experts and non-specialists in accounting and financial reporting, with equal representation from both groups. This approach was chosen based on the rationale that accountability challenges affect individuals, regardless of their expertise in financial matters. While non-financial experts may lack the technical proficiency to interpret financial statements, they possess clear expectations concerning the government's accountability for the management of public financial resources.

Table 1.

Sample Selection Matrix (Sampling Grid) for the Study.

Table 1.

Sample Selection Matrix (Sampling Grid) for the Study.

| User Groups |

Financial Experts |

Non-Financial Experts |

Total |

Report-Preparers

and Auditors |

5 |

0 |

5 |

| Financial Analysts |

5 |

0 |

5 |

| Academics |

1 |

4 |

5 |

| Legislators |

1 |

4 |

5 |

| Public Affairs Analysts |

0 |

5 |

5 |

| Total |

12 |

13 |

25 |

6. Analytical Method

For this research modified and employed Braun and Clark's (2006) approach to thematic analysis with some adaptations, utilizing NVivo 11 Pro software to analyze the interview dataset. We began by thoroughly reviewing the interview transcripts, and the coding technique was employed to identify pertinent themes. Through a process of reflective and inductive reasoning, was developed and elucidated the final themes. These themes played a pivotal role in addressing the research questions.

7. Discussion of Findings

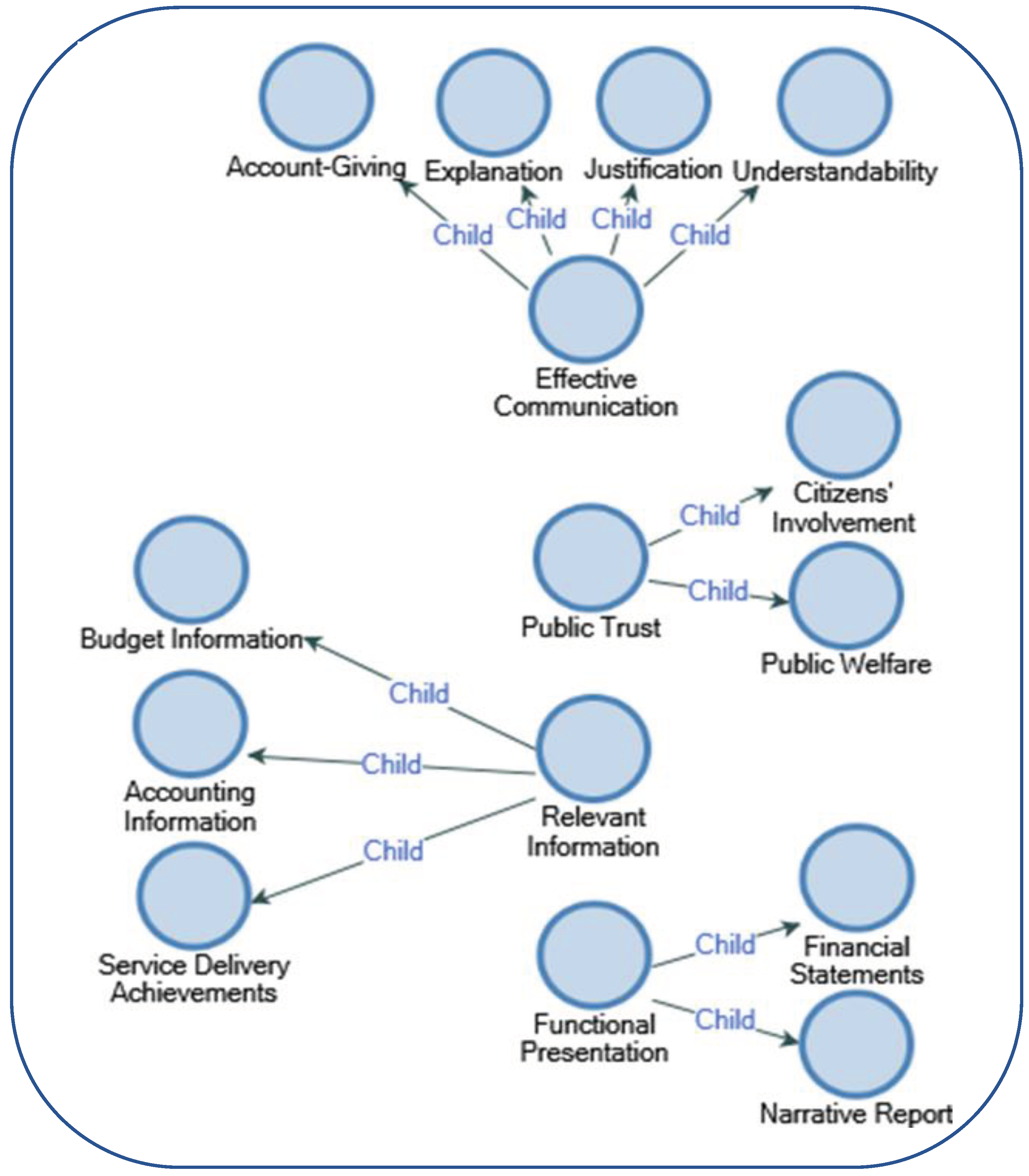

The primary findings from the thematic analysis of the research data are visually represented in

Figure 1, which is a project map created in NVivo. This map outlines four overarching themes and 11 underlying secondary themes (categories) that surfaced during the analytical process. These themes collectively provide a comprehensive overview of the participants' perspectives on the fundamental concepts of public accountability and their concerns related to financial reporting as a means for the government to fulfill its domestic accountability obligations.

The two prominent themes, "effective communication" and "public trust," encapsulate the collective perspective of the interview participants regarding the essence of public financial accountability. According to the participants, accountability is fundamentally about the government's duty to provide a comprehensive account by proficiently communicating its decisions, actions, and the outcomes of its responsibilities. This entails that decisions and actions are presented in a manner that is both transparent and understandable to the intended audience.

The process of explanation serves as a mechanism for answerability, delineating what was done and how it was done. Justification, on the other hand, offers rationales for the decisions and actions, along with supporting evidence demonstrating the outcomes of such decisions and actions. Justification essentially provides evidence-based information to establish that what was done and how it was done align with principles of fairness and correctness. It serves as a form of defense for public decisions and actions. Without sufficient reasons and evidence for decisions and actions, evaluating or judging performance would be a futile endeavor.

The study has discovered that citizens' comprehension of public accountability surpasses the formal definition of the concept, which is typically associated with the effective communication of decisions, actions, and results. Instead, participants perceive the true essence of public accountability as the fulfillment of public trust. In this context, public financial accountability becomes a means by which the government earns and maintains the trust of its citizens in its management of public financial resources for the greater public interest and welfare.

Account-rendering, therefore, serves as a tangible demonstration of the government's commitment to fulfilling public trust. This is achieved through the regular and thorough explanation and justification of public policies, decisions, actions, and their associated outcomes. Notably, this perspective on accountability goes beyond the scope of discussion found in traditional financial reporting literature.

To encapsulate this perspective, one of the research participants succinctly summarizes the concept of public accountability as follows:

“The true measurement of whether the government is accountable or not is whether it has met the interests and aspirations of the people. That is what it is. So, what are we trying to say? Leadership is about the responsibility to fulfil trust” (RP22).

The findings of this study, particularly in regard to the core concept of public accountability, carry significant implications for financial reporting in the public sector. Essentially, financial reports should serve as a means to demonstrate how the government has either fulfilled or is actively fulfilling the trust that the public has placed in them to manage public financial resources for the betterment of society. In line with this, to effectively serve the purpose of accountability, public-sector financial reports must furnish information that empowers primary users to evaluate and pass judgment on the government's performance in upholding its responsibility to fulfill public trust.

The thematic category labeled 'relevant information,' as represented in the NVivo project map (

Figure 1), succinctly captures the viewpoints and expectations expressed within the dataset regarding the fundamental information that interview participants anticipate from public-sector financial reports. Participants have discerned three crucial strands of information as vital to address their accounting needs, and these are budget information, accounting information and service delivery achievements.

In essence, any financial report crafted with the intent of serving accountability purposes must create a clear and coherent linkage between the allocation of planned financial resources and their actual expenditure (budget information), the management of substantial financial resources and expenditures (accounting information), and the concrete results of budget implementation, as demonstrated through service delivery achievements. This comprehensive approach ensures that financial reporting meets the diverse needs and expectations of users, thereby facilitating transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making.

The journey to fulfilling public trust commences with the formulation of the public budget. The annual budget serves as a financial embodiment of the government's intentions for service delivery, an expression of these intentions that have received endorsement from the people through their elected representatives. Participants in this study perceive every annual financial report as a reflection of the budget's execution. In other words, it is a report that should elucidate and justify the decisions and actions taken by the government to implement the approved budget and attain its objectives. The credibility of the budget is instrumental in shaping the accountability value of financial reports. A credible budget reflects the government's commitment to align its financial plans with public needs and expectations. Therefore, budgeting can be aptly considered as the inception of the accountability process. Furthermore, since the budget typically carries the weight of an appropriation law, compliance with the budget provisions is not just a matter of good practice but a legal requirement.

Participants express a strong expectation for a well-defined and logical connection between the budget and the financial report. This connection should extend beyond merely focusing on budgeted amounts to encompass the actual implementation of programs, projects, and the anticipated outcomes. For participants, what truly matters for the welfare of citizens is the successful realization of planned programs and projects, not just the monetary figures allocated, disbursed, and spent. In this context, the provision of clear and detailed descriptions of programs and projects, including their locations, is deemed as essential information by citizens for the sake of accountability. This information empowers citizens to understand how their government is working to improve their well-being and address their needs. Below are direct responses from interview participants that highlight the importance of this specific theme:

“There is supposed to be a relationship between the budget and the financial reports. The budget is a plan, what the government intends to do, while the financial report should explain the performance of the budget” (RP10).

"Budget is like a promise; what is intended to be done. People understand the budget and are happy to see what the government wants to do. At the end of the period, even within the period, people would expect to see that those things are being done" (RP11).

“The budget is actually a law; and compliance with the law is, for me, an important element of accountability” (RP14).

“It is not enough to just report on how public money is earned and spent. It is also required that the amount spent should be justified by the volume of achievement, the volume of work done, because expenditure is not necessarily achievement” (RP14).

The final theme, labeled 'functional presentation,' encapsulates the findings related to how information is presented in public financial reports, particularly how relevant information should be presented to achieve the essence of public financial accountability. The analysis of the data has unveiled a preference among report-users for financial reports presented in written narrative form alone or in a combination of narrative and accounting language. Interestingly, participants have expressed a distinct aversion to relying solely on traditional annual accounts or financial statements as the exclusive form of financial accountability reporting by the government.

"There is a need to have a textual explanation of the figures. If I had a word explanation of what the reports are talking about, it would be clearer and easier for me to understand what has been done. That would be better accounting for me" (RP17).

"But it is very necessary that the financial reports are presented in a manner that the public can understand. In that case, I support those financial reports should include narratives. The narratives can be in the form of notes, pictorial or appendix to the financial statements; it can also be presented as a separate report but incorporated in the financial report" (RP8).

"At the present, the reports are presented in much more figures than words, but we expect that more words should be used; that is, the report should contain more textual information than it currently does. I am satisfied with the textual information I find in the budget. If the financial reports can provide even half of such textual information, that would be a significant improvement" (RP14).

8. Conclusion and Implications

This study researched into the essence of financial accountability and examined the implications of its findings for financial reporting within the public sector. It adopted a perspective that focused on the needs and expectations of report-users, operating under the premise that public accountability primarily addresses governance issues through the lens of the citizenry. It recognized that the established fundamental qualitative characteristic of financial information is its relevance to the users, aligning with their specific requirements. The study operated with the assumption that the ultimate purpose or essence of public accountability is not explicitly defined in the existing body of public accounting and financial reporting literature. This knowledge gap regarding the intrinsic nature of public accountability is posited as a latent reason for the accountability shortcomings observed in financial reporting within the public sector across numerous countries.

A qualitative analysis of research data generated through in-depth personal interviews of 25 Nigerians selected purposively across professions and vocations reveals that citizens understand the essence of public accountability as a conscious commitment by the government to fulfil public trust and citizens’ rights. Thus, the real meaning of public financial accountability is the fulfilment of citizens’ trust in the government to manage public financial resources for the interest and benefits of the public and to communicate significant decisions, actions and results relating regularly and effectively to the discharge of this responsibility to citizens.

The findings of this study carry several important implications for financial reporting in the public sector. First and foremost, policymakers need to acknowledge that financial reporting in the public sector is fundamentally a form of accountability reporting. It serves as a performative manifestation of accountability, as described by Dubnick and Justice (2004). Financial reporting in this context goes beyond the mere presentation of financial accounts that adhere to local or international accounting standards. Users of public-sector financial reports are looking for more than just information explaining how public revenues are raised and spent. The primary responsibility of public finance managers, in light of these findings, is to provide credible information that empowers users to assess whether their trust in the government to meet their basic welfare needs is being fulfilled.

To fulfill this obligation effectively, especially in jurisdictions grappling with the issue of public corruption, public-sector financial reporting must go beyond the basic requirements and provide supplementary and complementary information. This additional information should establish clear linkages between budget provisions, actual accounting results, and the tangible achievements in service delivery.

In jurisdictions where public corruption is a challenge, such supplementary information becomes even more crucial. It can help in building and maintaining citizens' trust by demonstrating that public resources are utilized for their benefit. It goes beyond the mere fulfillment of legal and administrative obligations to provide financial statements.

Secondly, it is imperative to undertake a systematic exploration of citizens' expectations that are inherently bound to public trust and to ensure that these expectations are duly incorporated into the statutory financial reports of public entities. Accountability, as per the insights provided by Dubnick and Romzek (1991), is intricately linked to managing expectations and is fundamentally a social construct shaped by human perception. Therefore, financial accountability reporting must be reflective of the unique contextual realities within the reporting environment. This study is expected to stimulate further research and discourse on this subject to broaden our understanding of the intricacies of financial accountability reporting within the public sector. It is also advisable to include the essence of financial accountability as a mission statement within the accounting policies section of statutory financial reports for public entities. This mission statement can serve as a guiding beacon for both those who prepare financial reports and those who use them, reaffirming the commitment to transparency, trust, and accountability in the realm of public finance.

References

- Ackerman, J.M. Social Accountability in the Public Sector: A Conceptual Discussion. Soc. Dev. Pap. : Particip. Civ. Engagem. 2005, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.M. Re-conceptualization of Accountability: From Government to Governance. Int. J. Multidiscip. Approach Stud. 2016, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Akhidime, A. Accountability and Financial Reporting in Nigeria Public Financial Management: An Empirical Exploration. Knowl. Rev. 2011, 26, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Akpanuko, E.E. & Asogwa, I.E. Accountability: A Synthesis. Int. J. Financ. Account. 2013, 2, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruwa, S.A.S. (2003). Government Financial Reporting and Public Accountability in Nigeria, /: Available from: https, 17 February 2850. [Google Scholar]

- Aruwa, S.A.S. (2005). The Quality of the Information Content of Published Government Financial Statements, /: Available from: https, 2 January 3058. [Google Scholar]

- Asechemie, D.P.S. (1995). Anatomy of Public Sector Accounting in Nigeria.

- Bovens, M. A framework for the Analysis and Assessment of Accountability Arrangements in the Public Domain. Democracy and accountability in the EU. Eur. Law J. 1998, 13, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M. (2005). Public Accountability. O: E., Lynn, L.E. & Pollute, C. eds. The Oxford Handbook of Public Management. New York.

- Bovens, M. Analyzing and Assessing Public Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. European Governance Papers. Eur. Law J. 2006, 13, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M. , Schillemans, T. & Goodin, R.E. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendon, A.B. (2011). Accountability and Public Administration: Concepts, Dimensions, Development, p: Available from, 29 December 0065. [Google Scholar]

- Chahed, Y. (2009). Mistrust in Numbers: The Rise of Non-Financial and Future-Oriented Reporting in UK Accounting Reporting in the 1990s.

- Chan, J.L. (1992). The Governmental Environment: Characteristics and Influences on Governmental Accounting and Financial Reporting. J: N.G. & Crumbley, D.L. eds. Handbook of Governmental Accounting and Finance. New York.

- Chan, J.L. (2006). IPSAS and Government Accounting Reform in Developing Countries. In: E. Lande and J.-C. Scheid, M: Accounting Reform in the Public Sector. [CrossRef]

- Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA), (2018) An Introductory Guide to Financial Reporting in the Public Sector in the United Kingdom [Online]. Available from: http://www.cipfa.org/policy-and-guidance/publications [Accessed ]. 25 December.

- Chatterjee, B.; Mirshekary, S. & Safarib, M. Users’ Information Requirements and Narrative Reporting: The Case of Iranian Companies. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2010, 4, 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C. Understanding the Needs of Users of Public Sector Financial Reports: How Far Have We Come? Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2010, 6, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cordery, C.J. & Simpkins, K. Financial Reporting Standards for the Public Sector: New Zealand’s 21st-Century Experience. Public Money Manag. [CrossRef]

- Coy, D.; Fisher, M. & Gordon, T. Public Accountability: A New Paradigm for College and University Annual Reports. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2001, 12, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L. , Certo, S.T., Ireland, R.D. & Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, J.P. (2009). The Power of Public Accountability, /: Available from: http, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dubnick, M.J. & Romzek, B.S. (1991). American Administration: Politics and the Management of Expectations.

- Dubnick, M.J. & Frederickson, H.J. Accountable Agents: Federal Performance Measurement and Third-Party Government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2010, 20, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubnick, M.J. & Justice, J.B. (2004). Accounting for Accountability, /: from: http, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Egbon, O. (2014). An Exploration of Accountability: Evidence from the Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry, U: Scotland.

- Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB), (2012). Handbook of Federal Accounting Standards and other Pronouncements, /: from: http, 24 February.

- Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach.

- Gray, A. & Jenkins, B. Codes of Accountability in the New Public Sector. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1993, 6, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GASB, (1987). Governmental Accounting Standard Series, [: from, 12 November.

- GASB, (1999). Governmental Accounting Standard Series, /: from: https, 12 November.

- Guthrie, J. & Parker, L.D. Corporate Social Reporting: A Rebuttal of Legitimacy Theory. Account. Bus. Res. 1989, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiling, J.; Schuhrer. S. & Chan, J. L New Development: Towards a Grand Convergence? International Proposals for Aligning Government Budgets, Accounts and Finance Statistics. Public Money Manag. 2013, 33, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, J.; Tooley, S; & Basnan, N. Performance Reporting: Assessing the Annual Reports of Malaysian Local Authorities. Int. J. Public Adm. 2012, 35, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J.J. & Boeije, H.R. (2005). Data Collection: Primary vs Secondary. In: Kempf-Leonard, K. ed. Encyclopaedia of Social Measurement. [CrossRef]

- International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), (2015). Accountability Now, /: from: http, 22 October.

- International Monetary Fund, (2007). Code of Good Practices on Fiscal Transparency, /: from: https, 10 March 2007.

- Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria (ICAN), (2014). Public Sector Accounting and Finance. Professional Student Study Pack.

- International Pubic-Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB), (2015). Conceptual Framework for General Purpose Financial Reporting by Public Entities, w: from, 9 August.

- Khan, M.K. (2006). Management Accountability for Public Financial Management, /: Available from: http, 10 August. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.M. , O’Flynn, J. & Sullivan, H. Accountability: To Whom, in Relation to What, and Why? Aust. J. Public Adm. 2015, 73, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mande, B. Perceptions on Government Financial Reporting in Nigeria. J. Financ. Account. Manag. 2015, 6, 2379–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, J. (2003). An Investigation of the Information Requirements of Users of Australian Public Sector Financial Reports.

- Mansbridge, J. (2014). A Contingency Theory of Accountabilit, U: M., Robert, E., Goodin, R.E. & Schillemans, T. eds. The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability. London, Oxford.

- Mulgan, R. , (2000). Holding Power to Account: Accountability in Modern Democracies, P: U.S.

- Omolehinwa, E. (2014). Public Financial Management: Issues and Challenges on Budget Performance. A Paper Presented at ICAN Symposium on Federal Government of Nigeria 2014 Budget at Muson Centre, Onikan Lagos on 15 July, /: Available from: http, 22 December.

- Premchand, A. (2001). Fiscal Transparency and Accountability: Ideal and Reality. Paper prepared for UN workshop on Financial Management and Accountability, Rome, Nov 28-30, /: Available from: http, 2 January.

- Proulx, V. (2012). Transnational Terrorism and State Accountability: A New Theory of Prevention.

- PwC, (2013). Integrated Reporting: Going Beyond the Financial Results, /: from: https, 3 December.

- Rayegan, M. , Parveizi, M., Nazari, K. & Emami, M. Government Accounting: An Assessment of Theory, Purposes and Standards. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business.

- Rixon, D.L. (2007). A Stakeholder Reporting Model for Semi-Autonomous Public-Sector Agencies: The Case of Workers Compensation Agency in Newfoundland, Canada.

- Romzek, B.S. Living Accountability: Hot rhetoric, Cool Theory, and Uneven Practice. Political Sci. Politics 2015, 48, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samkin, G. & Schneider, A. Accountability, Narrative Reporting and Legitimation: The case of a New Zealand public Benefit Entity. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2010, 23, 256–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillemans, T. & Busuioc, M. Predicting Public Sector Accountability: From Agency Drift to Forum Drift. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2014, 25, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, R. Exploring the Usefulness of a Conceptual Framework as a Research Tool: A Researcher's Reflections. Issues Educ. Res. 2004, 14, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Stapenhurst & O’Brien, (2015). Accountability in Governance - World Bank Group, /: from: https.

- Steccolini, I. (2004). Local Government Annual Report: An Accountability Medium? /: Available from: http, 9 August 8323. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J. (1984). The Role of Information in Public Accountability. In: Hopwood, A. & Tomkins, C. eds. Issues in Public Sector Accounting. [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M. (2015). Accounting for Accountability, /: Available from: https, 18 July.

- Transparency International (2014). Exporting Corruption: Progress Report 2014: Assessing Enforcement of The OECD Convention on Combating Foreign Bribery, /: from: http, 6 February.

- Transparency and Accountability Initiative (2017). Strategy 2017-2019, /: from: http, 14 January 2017.

- United Nations, (2001). Report of the Meeting of the Group of Experts on Globalization and new challenges of public finance. Financial management, transparency and accountability.

- Vance, A. , Lowry, P.B. & Eggett, D. (2015). Accountability Theory: IS Theory, /: from: https, 30 August.

- World Bank, (2004). Nigeria - State of Lagos financial accountability assessment, /: from: http, 30 August 2004.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).