Submitted:

27 October 2023

Posted:

31 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

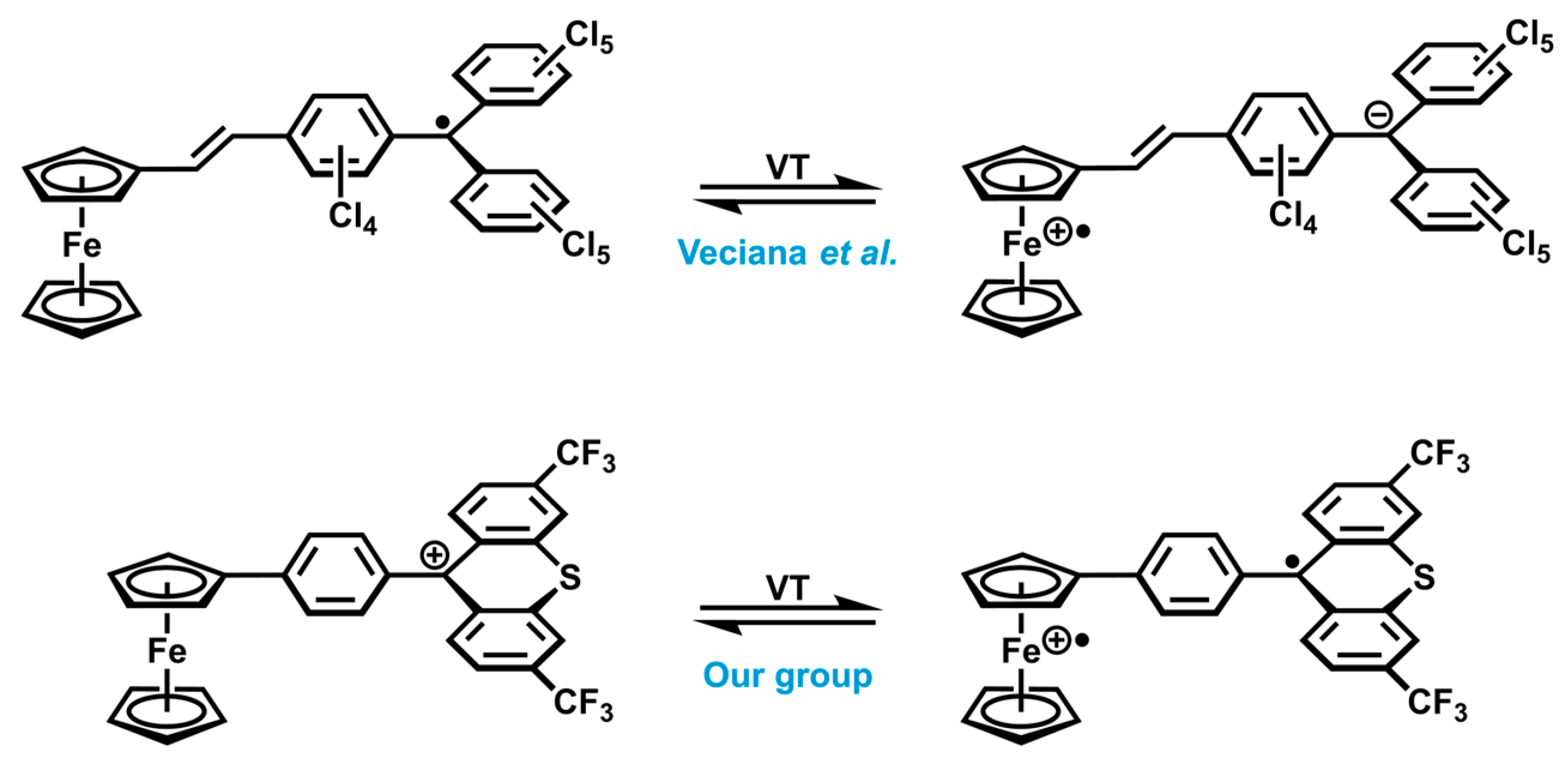

1. Introduction

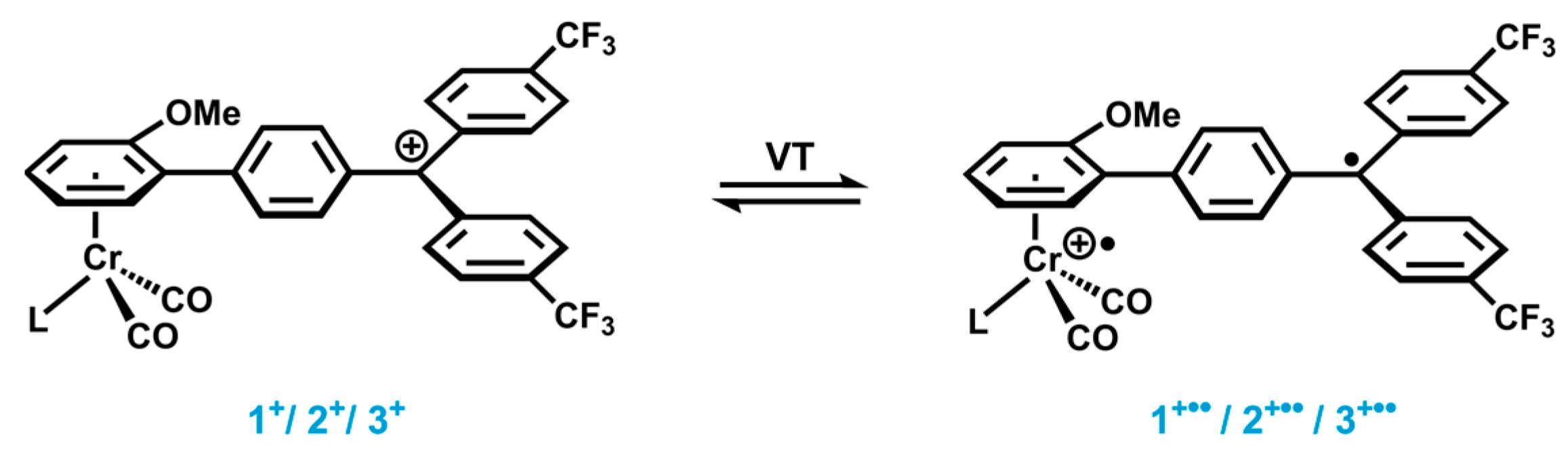

2. Results and Discussion

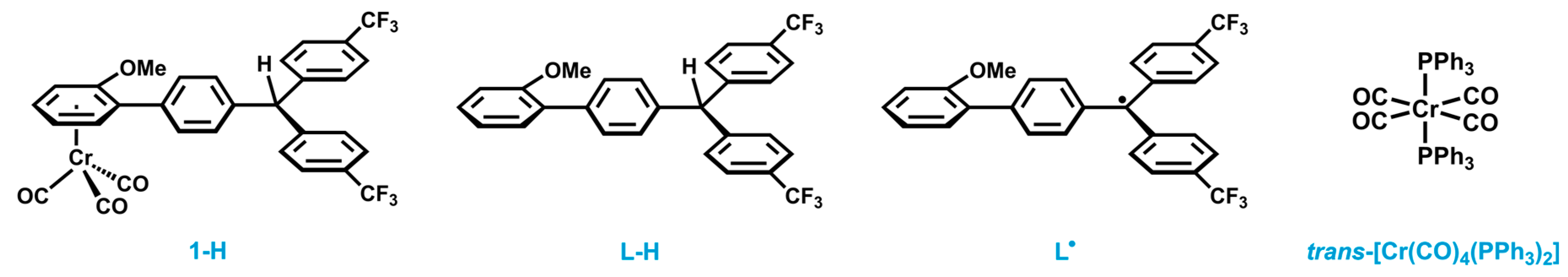

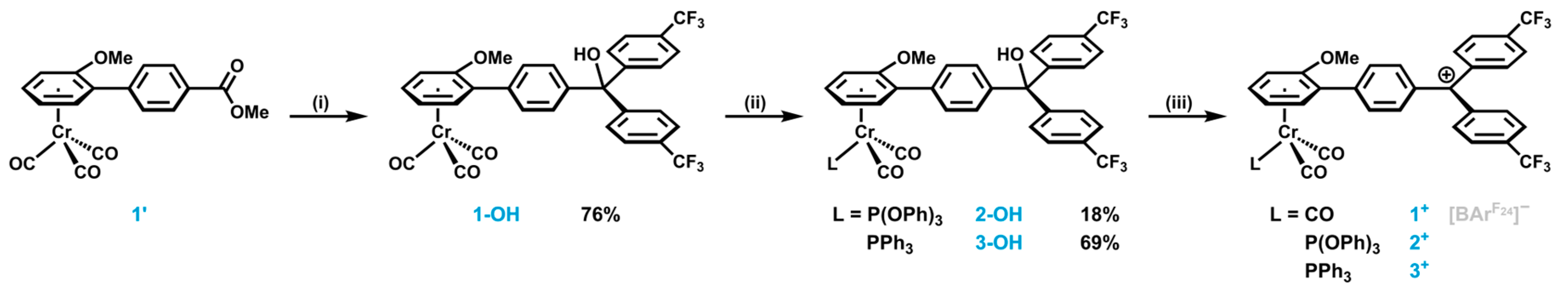

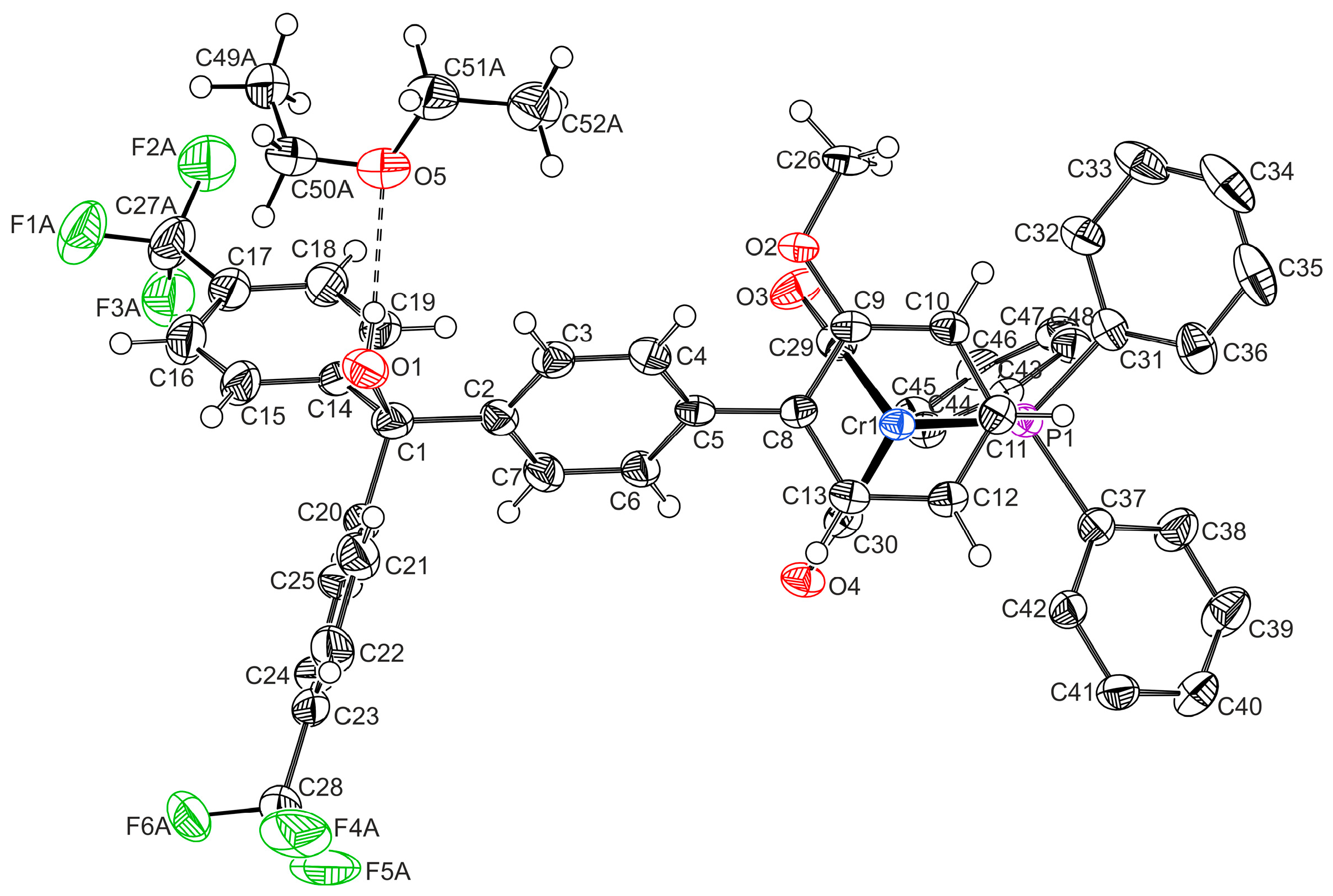

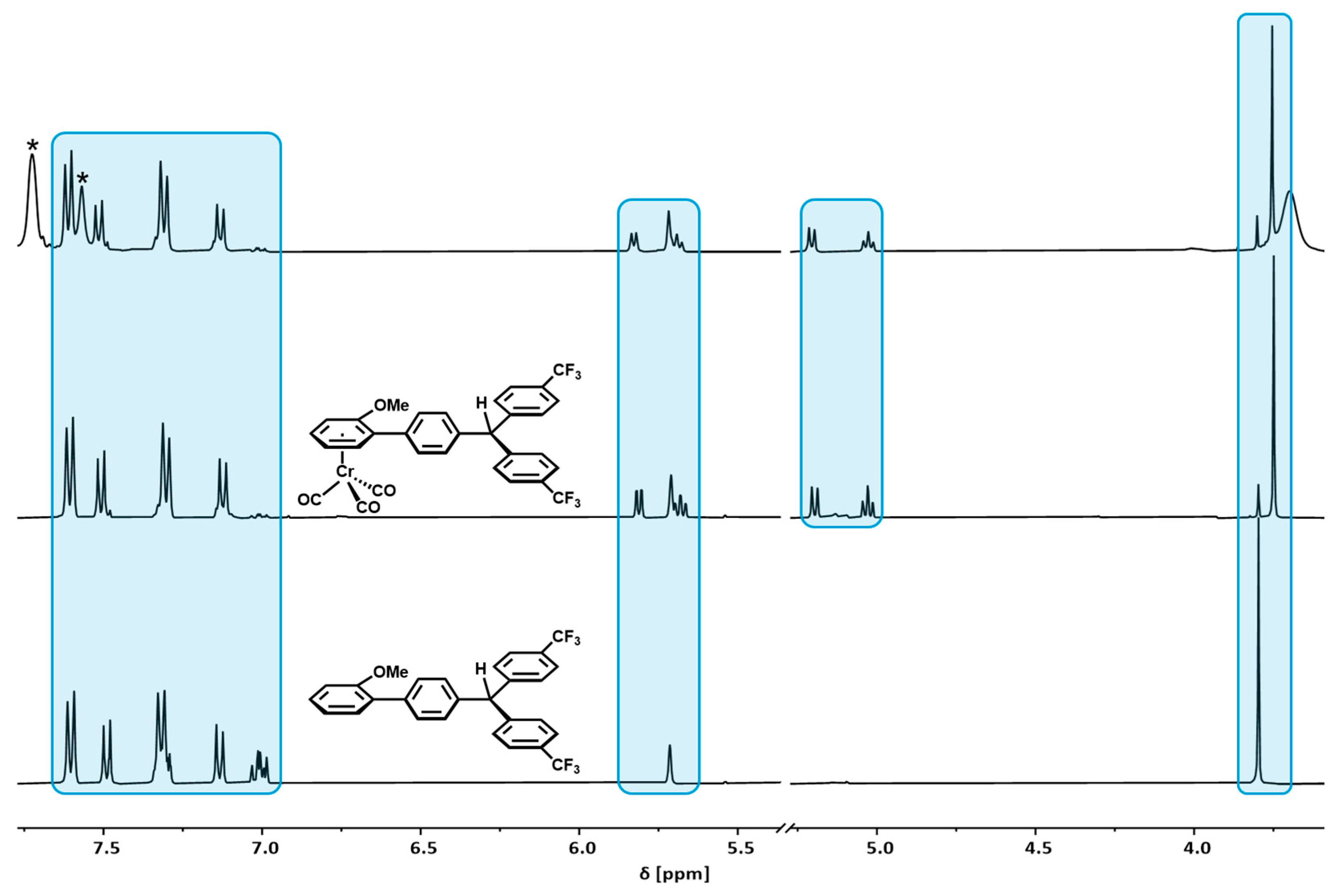

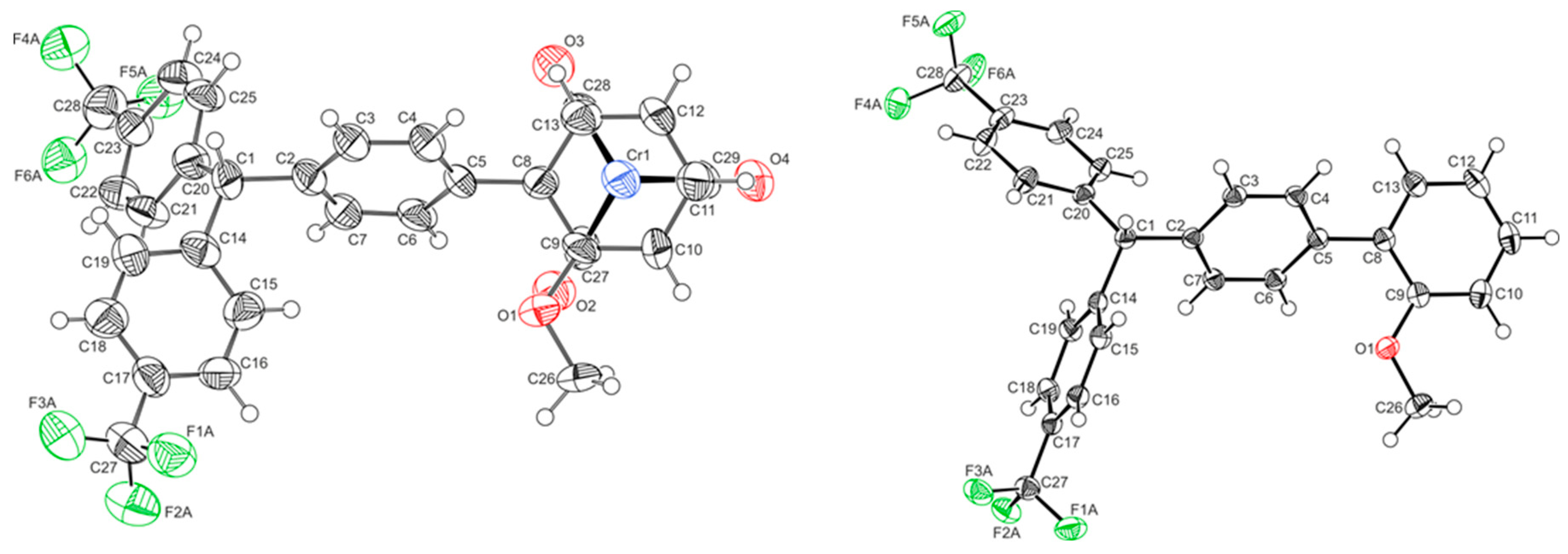

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

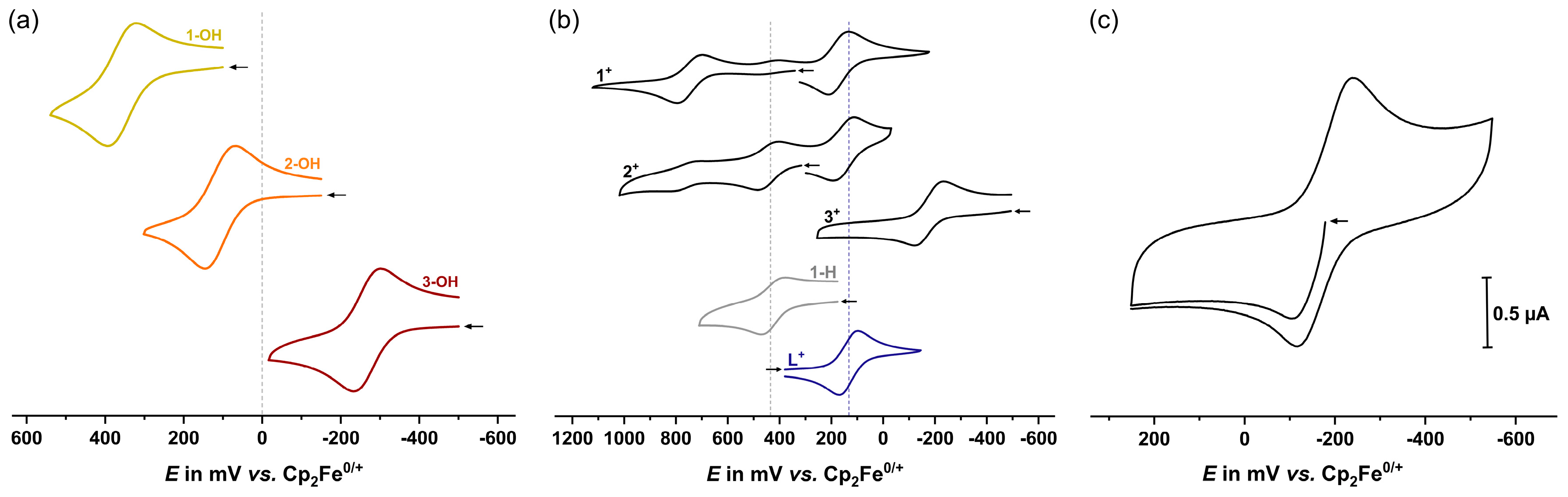

2.2. Electrochemistry

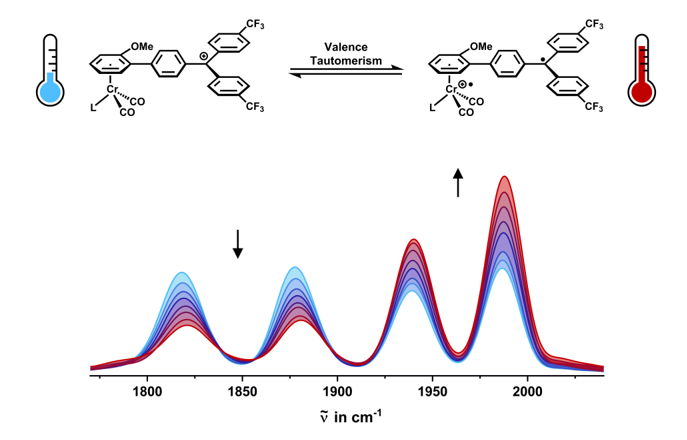

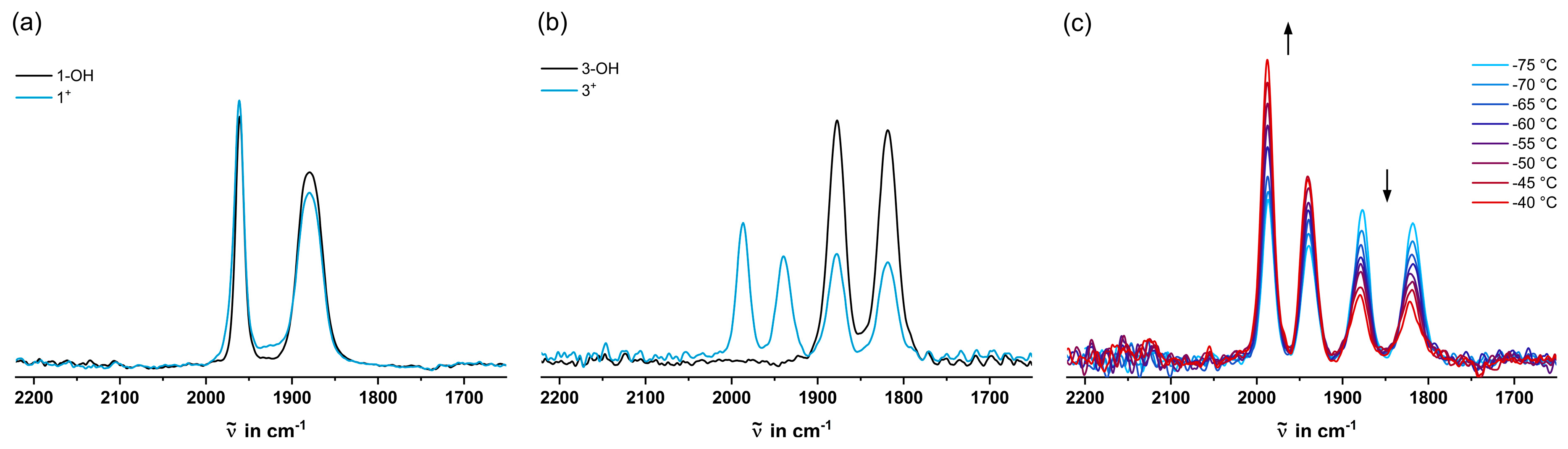

2.3. IR Spectroscopy

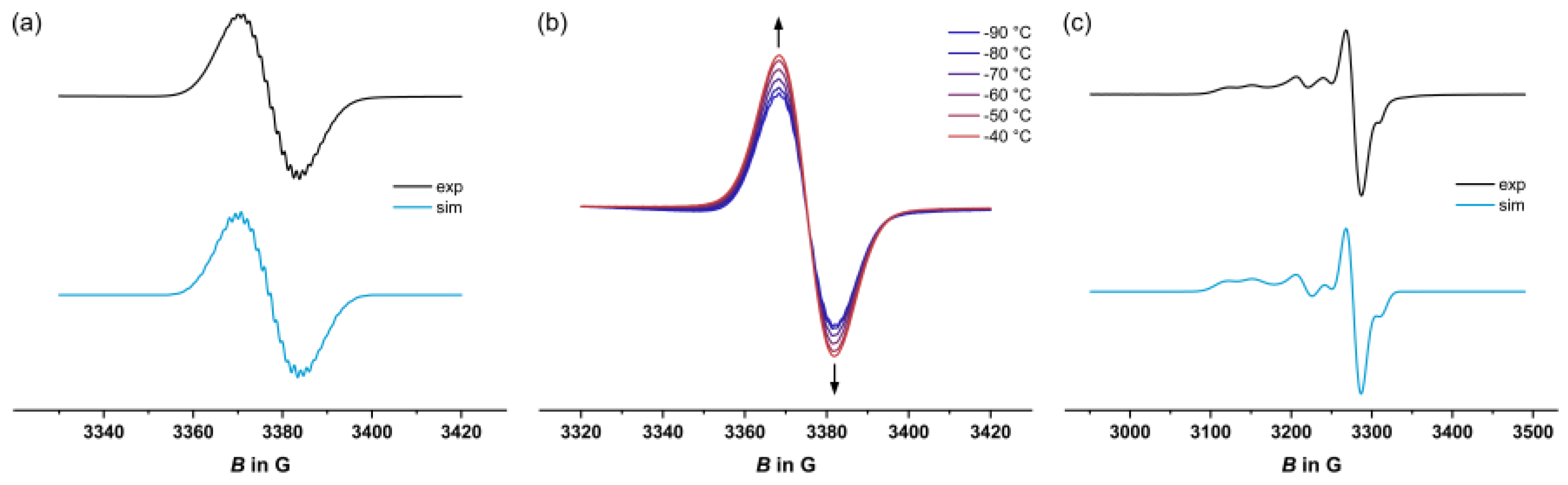

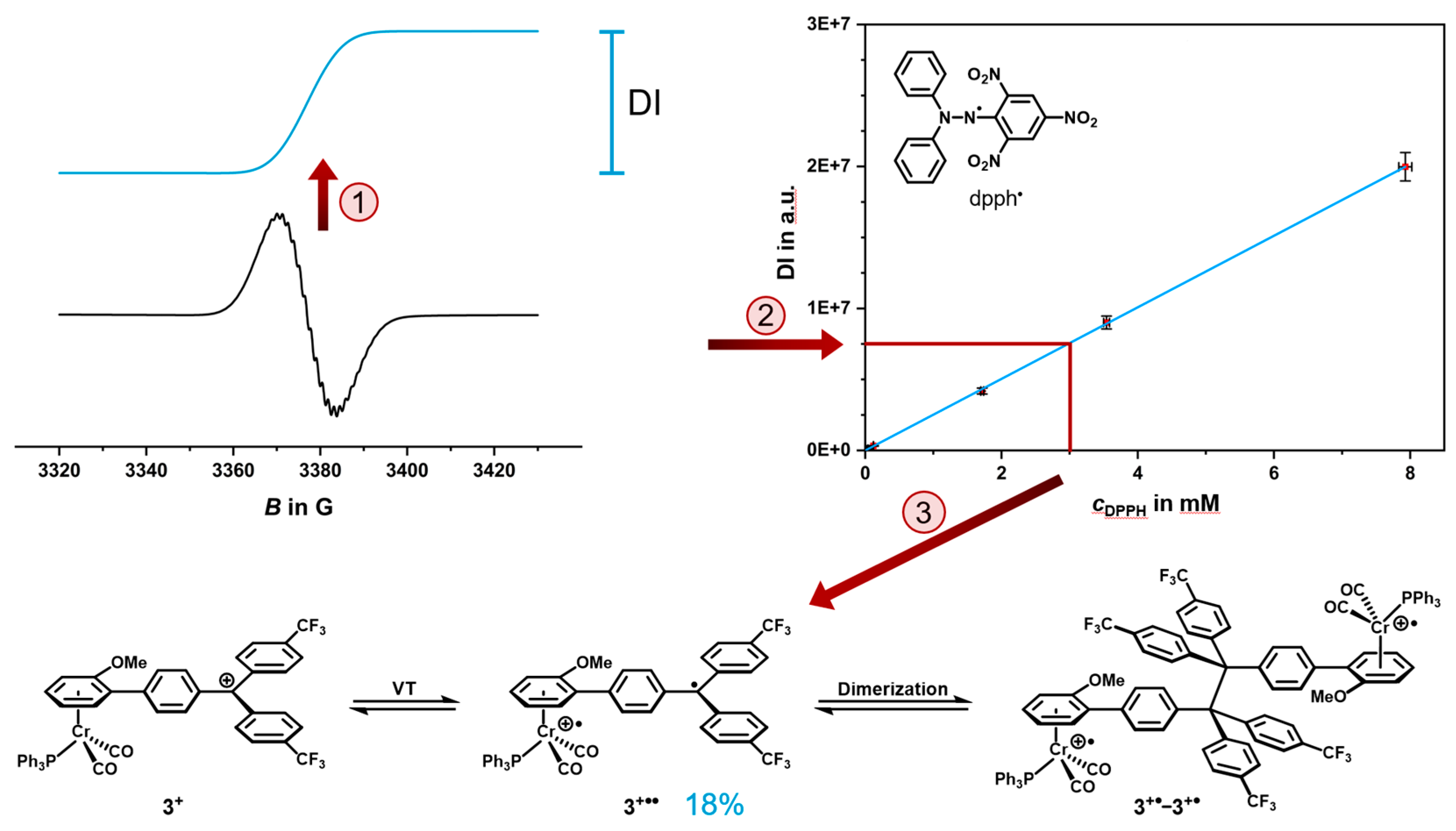

2.4. EPR Spectroscopy

| T in K | Metal-centered spin | Organic spin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g1 | g2 | g3 | A1 | A2 | A3 | giso | A | ||

| 1+ | 77 | -[a] | 2.003 | -[b] | |||||

| 203 | - | 2.005 | 5.4 (4H), 1.4 (2H), 2.7 (6F), 1.4 (1H) | ||||||

| 3+ | 77 | 2.095 | 2.031 | 1.991 | 34.6 (31P) | 33.9 (31P) | 27.8 (31P) | 2.003 | -[b] |

| 203 | - | 2.003 | 5.1 (4H), 1.4 (2H), 2.7 (6F), 1.4 (1H) | ||||||

2.5. Decomposition Pathways

4. Summary and Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Dedication

References

- Pierpont, C.G. Studies on charge distribution and valence tautomerism in transition metal complexes of catecholate and semiquinonate ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2001, 216, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.M.; Li, B.; Simon, J.D.; Hendrickson, D.N. Photoinduced Valence Tautomerism in Cobalt Complexes Containing Semiquinone Anion as Ligand: Dynamics of the High-Spin [CoII(3,5-dtbsq)2] to Low-Spin [CoIII(3,5-dtbsq)(3,5-dtbcat)] Interconversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995, 34, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.M.; Hendrickson, D.N. Pulsed Laser Photolysis and Thermodynamics Studies of Intramolecular Electron Transfer in Valence Tautomeric Cobalt o-Quinone Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11515–11528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, O.; Cui, A.; Matsuda, R.; Tao, J.; Hayami, S. Photo-induced Valence Tautomerism in Co Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Maruyama, H.; Sato, O. Valence Tautomeric Transitions with Thermal Hysteresis around Room Temperature and Photoinduced Effects Observed in a Cobalt−Tetraoxolene Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1790–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, T.M.; Gee, W.J.; Shepherd, H.J.; Warren, M.R.; Shultz, D.A.; Raithby, P.R.; Pinheiro, C.B. Hard X-ray-Induced Valence Tautomeric Interconversion in Cobalt-o-Dioxolene Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 4774–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poneti, G.; Mannini, M.; Sorace, L.; Sainctavit, P.; Arrio, M.-A.; Otero, E.; Criginski Cezar, J.; Dei, A. Soft-X-ray-Induced Redox Isomerism in a Cobalt Dioxolene Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1954–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, R.M.; Pierpont, C.G. Tautomeric Catecholate-Semiquinone Interconversion via Metal-Ligand Electron Transfer. Structural, Spectral, and Magnetic Properties of (3,5-Di-tert-butylcatecholato)-(3,5-di-tert-butylsemiquinone)(bipyridyl)cobalt(III), a Complex Containing Mixed-Valence Organic Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 4951–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caneschi, A.; Dei, A.; Fabrizi de Biani, F.; Gütlich, P.; Ksenofontov, V.; Levchenko, G.; Hoefer, A.; Renz, F. Pressure- and Temperature-Induced Valence Tautomeric Interconversion in a o-Dioxolene Adduct of a Cobalt-Tetraazamacrocycle Complex. Chem. Eur. J. 2001, 7, 3926–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonera, C.; Dei, A.; Létard, J.-F.; Sangregorio, C.; Sorace, L. Thermally and Light-Induced Valence Tautomeric Transition in a Dinuclear Cobalt–Tetraoxolene Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3136–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, L.; Francisco, T.M.; Shepherd, H.J.; Warren, M.R.; Saunders, L.K.; Shultz, D.A.; Raithby, P.R.; Pinheiro, C.B. Controlled Light and Temperature Induced Valence Tautomerism in a Cobalt-o-Dioxolene Complex. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 8665–8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratera, I.; Ruiz-Molina, D.; Renz, F.; Ensling, J.; Wurst, K.; Rovira, C.; Gütlich, P.; Veciana, J. A New Valence Tautomerism Example in an Electroactive Ferrocene Substituted Triphenylmethyl Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1462–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelio, E.; Ruiz-Molina, D. Valence Tautomerism: New Challenges for Electroactive Ligands. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 2005, 2957–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelio, E.; Ruiz-Molina, D. Valence tautomerism: More actors than just electroactive ligands and metal ions. C. R. Chim. 2008, 11, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezgerevska, T.; Alley, K.G.; Boskovic, C. Valence tautomerism in metal complexes: Stimulated and reversible intramolecular electron transfer between metal centers and organic ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 268, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, L.A.; Linseis, M.; Demeshko, S.; Azarkh, M.; Drescher, M.; Winter, R.F. Tailoring Valence Tautomerism by Using Redox Potentials: Studies on Ferrocene-Based Triarylmethylium Dyes with Electron-Poor Fluorenylium and Thioxanthylium Acceptors. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 10854–10868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, E.M.; Flowers, R.A.; Ludwig, R.T.; Meekhof, A.E.; Walek, S.A. Triarylmethanes and 9-arylxanthenes as prototypes amphihydric compounds for relating the stabilities of cations, anions and radicals by C-H bond cleavage and electron transfer. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 1997, 10, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Handoo, K.L.; Parker, V.D. Hydride affinities of carbenium ions in acetonitrile and dimethyl sulfoxide solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 2655–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, R.; Mazur, S. Electrochemical determination of pKR+ for some antiaromatic cyclopentadienyl cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 584–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohbusch, F. Polarographische Untersuchungen der Substituenteneffekte in Triarylmethylkationen. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 1972, 76, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nau, M.; Casper, L.A.; Haug, G.; Linseis, M.; Demeshko, S.; Winter, R.F. Linker permethylation as a means to foster valence tautomerism and thwart dimerization in ferrocenyl-triarylmethylium cations. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 4674–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, R. Electronic structure of the ferricenium cation. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, R.; Reinders, F.J. Electron spin resonance of the cation of ferrocene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 4929–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.O.; Öfele, K. Über Aromatenkomplexe von Metallen, XIII Benzol-Chrom-Tricarbonyl. Chem. Ber. 1957, 90, 2532–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Djukic, J.-P.; Michon, C. Metalated (η6-arene)tricarbonylchromium complexes in organometallic chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 225, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosillo, M.; Domínguez, G.; Pérez-Castells, J. Chromium arene complexes in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1589–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semmelhack, M.F. Transition Metal Arene Complexes: Nucleophilic Addition. In Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry II; Elsevier, 1995; pp. 979–1015. ISBN 9780080465197. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, B.; Whiting, M.C. The Organic Chemistry of the Transition Elements. Part I. Tricarbonylchromium Derivatives of Aromatic Compounds. J. Chem. Soc. 1959, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, W. Eine verbesserte Darstellung von Aromaten- und Cycloheptatrien-Chromtricarbonylen. Chem. Ber. 1961, 94, 2490–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffy, C.A.L.; Pauson, P.L.; Rausch, M.D.; Lee, W. (η6-Arene)Tricarbonylchromium Complexes. In Inorganic Syntheses; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1979; pp. 154–158. ISBN 9780470132500. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, N.G.; Demidowicz, Z.; Kelly, R.L. Reactions of tricarbonyl(η-hexamethylbenzene)chromium derivatives with nitrosonium and benzenediazonium ions: reversible oxidation versus nitrosyl- or areneazo-complex formation. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1975, 2335–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohrenberg, N.C.; Paradee, L.M.; DeWitte, R.J.; Chong, D.; Geiger, W.E. Spectra and Synthetic-Time-Scale Substitution Reactions of Electrochemically Produced [Cr(CO)3(η6-arene)]+ Complexes. Organometallics 2010, 29, 3179–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Order Jr, N.; Geiger, W.E.; Bitterwolf, T.E.; Rheingold, A.L. Mixed-valent cations of dinuclear chromium arene complexes: electrochemical, spectroscopic, and structural considerations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 5680–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, D.T.; Geiger, W.E. Mixed-valent interactions in rigid dinuclear systems: electrochemical and spectroscopic studies of CrICr0 ions with controlled torsion of the biphenyl bridge. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, M.P.; Connelly, N.G.; Pike, R.D.; Rieger, A.L.; Rieger, P.H. EPR Spectra of [Cr(CO)2L(η-C6Me6)]+ (L= PEt3, PPh3, P(OEt)3, P(OPh)3): Analysis of Line Widths and Determination of Ground State Configuration from Interpretation of 31P Couplings. Organometallics 1997, 16, 4369–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoi, Y.; Okano, K.; Tokuyama, H. Generation of Aryl Grignard Reagents from Arene Chromium Tricarbonyl Complexes by Mg(TMP)2·2LiCl and Their Application to Murahashi Coupling. Synlett 2014, 25, 2503–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmeier, W.; Hellmann, H. Photochemisch hergestellte Derivate von Aromatenchromtricarbonylen und ihre Stabilität als Funktion der Substituenten am Benzolring. Chem. Ber. 1963, 96, 2859–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cais, M.; Kaftory, M.; Kohn, D.H.; Tatarsky, D. Structural and Catalytic Activity Studies on Phosphine- and Phosphite-Dicarbonylchromium Complexes of Phenanthrene and Naphthalene. J. Organomet. Chem. 1980, 184, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookhart, M.; Grant, B.; Volpe Jr., A.F. [(3,5-(CF3)2C6H3)4B]-[H(OEt2)2]+: A Convenient Reagent for Generation and Stabilization of Cationic, Highly Electrophilic Organometallic Complexes. Organometallics 1992, 11, 3920–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oßwald, S.; Casper, L.A.; Anders, P.; Schiebel, E.; Demeshko, S.; Winter, R.F. Electrochemical, Spectroelectrochemical, Mößbauer, and EPR Spectroscopic Studies on Ferrocenyl-Substituted Tritylium Dyes. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12524–12538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, L.A.; Oßwald, S.; Anders, P.; Rosenbaum, L.-C.; Winter, R.F. Extremely Electron-Poor Bis(diarylmethylium)-Substituted Ferrocenes and the First Peroxoferrocenophane. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2020, 646, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, L.A.; Wursthorn, L.; Geppert, M.; Roser, P.; Linseis, M.; Drescher, M.; Winter, R.F. 4-Ferrocenylphenyl-Substituted Tritylium Dyes with Open and Interlinked C+Ar2 Entities: Redox Behavior, Electrochromism, and a Quantitative Study of the Dimerization of Their Neutral Radicals. Organometallics 2020, 39, 3275–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.-L.; White, A.J.P.; Widdowson, D.A.; Wilhelm, R.; Williams, D.J. Dilithiation of arenetricarbonylchromium(0) complexes with enantioselective quench: application to chiral biaryl synthesis. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2001, 3269–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, M.; Nishikawa, N.; Take, K.; Ohnishi, M.; Hirotsu, K.; Higuchi, T.; Hayashi, Y. Arene-metal complex in organic synthesis: directed regioselective lithiation of (π-substituted benzene)chromium tricarbonyl complexes. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 2349–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, O.L.; McPhail, A.T.; Sim, G.A. Metal–carbonyl and metal–nitrosyl complexes. Part II. Crystal and molecular structure of the tricarbonylchromiumanisole–1,3,5-trinitrobenzene complex. J. Chem. Soc. A 1966, 822–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberico, E.; Braun, W.; Calmuschi-Cula, B.; Englert, U.; Salzer, A.; Totev, D. Expanding the Range of “Daniphos”-Type P∩P- and P∩N-Ligands: Synthesis and Structural Characterisation of New [(η6-arene)Cr(CO)3] Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 2007, 4923–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambie, R.C.; Clark, G.R.; Gourdie, A.C.; Rutledge, P.S.; Woodgate, P.D. Synthesis and crystal structures of the α and β stereoisomers of tricarbonyl[(8,9,11,12,13,14-η)-methyl 12-methoxypodocarpa-8,11,13-trien-19-oate]chromium. J. Organomet. Chem. 1985, 297, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilday, J.P.; Widdowson, D.A. Lithiation of 2-, 3-, and 4-fluoroanisole(tricarbonyl)chromium(0) complexes: a reversal of normal regiocontrol. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1986, 1235–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batuecas, M.; Luo, J.; Gergelitsová, I.; Krämer, K.; Whitaker, D.; Vitorica-Yrezabal, I.J.; Larrosa, I. Catalytic Asymmetric C-H Arylation of (η6-Arene)Chromium Complexes: Facile Access to Planar-Chiral Phosphines. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 5268–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camire, N.; Nafady, A.; Geiger, W.E. Characterization and Reactions of Previously Elusive 17-Electron Cations: Electrochemical Oxidations of (C6H6)Cr(CO)3 and (C5H5)Co(CO)2 in the Presence of [B(C6F5)4]-. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7260–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D. Hunter; Vivian Mozol; Stanislaus D. Tsai. Nonlinear Substituent Interactions and the Electron Richness of Substituted (η6-Arene)Cr(CO)3 Complexes as Measured by IR and 13C NMR Spectroscopy and Cyclic Voltammetry: Role of π-Donor and π-Acceptor Interactions. Organometallics 1992, 11, 2251–2262. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, N.G.; Geiger, W.E. Chemical redox agents for organometallic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 877–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, A.B.P. Electrochemical Parametrization of Metal Complex Redox Potentials, Using the Ruthenium(III)/Ruthenium(II) Couple to Generate a Ligand Electrochemical Series. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 1271–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.E.; Taube, H. Determination of E20-E10 in multistep charge transfer by stationary-electrode pulse and cyclic voltammetry: application to binuclear ruthenium ammines. Inorg. Chem. 1981, 20, 1278–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaffy, C.A.L.; Pauson, P.L.; Rausch, M.D.; Lee, W. (η6-Arene)Tricarbonylchromium Complexes. In Reagents for transition metal complex and organometallic syntheses; Angelici, R.J., Basolo, F., Eds.; Wiley: New York, 1990; pp. 136–140. ISBN 9780470132593. [Google Scholar]

- Trapp, C.; Wang, C.-S.; Filler, R. Electron Spin Resonance Absorption in the Tris(pentafluorophenyl)methyl Radical. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 45, 3472–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, K.F.; Battke, D.; Golz, P.; Rupf, S.M.; Malischewski, M.; Riedel, S. The Tris(pentafluorophenyl)methylium Cation: Isolation and Reactivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202203777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, S.; Schweiger, A. EasySpin, a comprehensive software package for spectral simulation and analysis in EPR. J. Magn. Reson. 2006, 178, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, S.S.; Eaton, G.R. Signal Area Measurements in EPR. Bull. Magn. Reson. 1980, 1, 130–138. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, A.N.; Kittel, C.; Merritt, F.R.; Yager, W.A. Determination of g-Values in Paramagnetic Organic Compounds by Microwave Resonance. Phys. Rev. 1950, 77, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, R.N.; Bond, A.M.; Brain, G.; Colton, R.; Henderson, T.L.E.; Kevekordes, J.E. Electrochemical, chemical and spectroscopic characterization of the trans-[tetracarbonylbis(triphenylphosphine)chromium]+/0 redox couple. Organometallics 1984, 3, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.M.; Colton, R.; Kevekordes, J.E. Redox reactions of chromium tetracarbonyl and tricarbonyl complexes: thermodynamic, kinetic, and catalytic aspects of isomerization in the fac/mer-tricarbonyltris(trimethyl phosphite)chromium(1+/0) system. Inorg. Chem. 1986, 25, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, A.D.; Shilliday, L.; Furey, W.S.; Zaworotko, M.J. Substituent interactions in η6-arene complexes. 1. Systematic x-ray crystallographic study of the structural manifestations of π-donor and π-acceptor substituent effects in substituted chromium (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 complexes. Organometallics 1992, 11, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reger, D.L.; Wright, T.D.; Little, C.A.; Lamba, J.J.S.; Smith, M.D. Control of the Stereochemical Impact of the Lone Pair in Lead(II) Tris(pyrazolyl)methane Complexes. Improved Preparation of Na{B [3,5-(CF3)2C6H3]4}. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 3810–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Josowicz, M.; Tolbert, L.M. Diferrocenyl Molecular Wires. The Role of Heteroatom Linkers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 10374–10382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, G.; Weakley, T.J.R.; Weissensteiner, W. The Triphenylphosphine Cone Angle and Restricted Rotation about the Chromium–Phosphorus Bond in Dicarbonyl(η6-hexa-alkylbenzene)(triphenylphosphine)chromium(0) Complexes. Crystal and Molecular Structure of Dicarbonyl(η6-hexa-n-propylbenzene)(triphenylphosphine)chromium(0). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1987, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzert, D.; Holstein, J.J.; Krossing, I. DSR: enhanced modelling and refinement of disordered structures with SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1′ | 3-OH | 1-H | L-H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal system | triclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | orthorhombic |

| Space group | P21/c | P21/n | Pbca | |

| ∠PhCr-Ph1 | 53.63(17)° | 52.55(14)° | 55.3(5)° | 47.09(8)° |

| ∠Ph1-Ph2 | n.a. | 75.00(16)° | 78.1(5)° | 77.00(8)° |

| ∠Ph1-Ph3 | n.a. | 76.50(18)° | 84.1(5)° | 82.95(8)° |

| ∠Ph1-C-OH | n.a. | 110.1(3)° | n.a. | n.a. |

| ∠Ph2-C-OH | n.a. | 105.9(3)° | n.a. | n.a. |

| ∠Ph3-C-OH | n.a. | 106.8(3)° | n.a. | n.a. |

| d C-OH | n.a. | 1.433(4) | n.a. | n.a. |

| d Cr-PhCr | 1.7151(5) | 1.703(5) | 1.720(5) | n.a. |

| d Cr-CO1 | 1.837(4) | 1.821(3) | 1.819(12) | n.a. |

| d Cr-CO2 | 1.837(3) | 1.810(3) | 1.786(12) | n.a. |

| d Cr-CO3/P | 1.844(5) | 2.303(1) | 1.801(12) | n.a. |

| Oxidation | Reduction | Potential Difference |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1/2 | ΔEp | E1/2 | ΔEp | ΔE1/2 | |

| 1-OH | 360 | 71 | - | - | - |

| 2-OH | 110 | 81 | - | - | - |

| 3-OH | -265 | 68 | - | - | - |

| 1+[a] | 750 | 96 | 175 | 78 | 575 |

| 2+[b] | 445 | 77 | 155 | 79 | 290 |

| 3+[c] | -180 | 110 | -180 | 110 | < 50 |

| 1-H | 435 | 83 | - | - | - |

| L+ | - | - | 135 | 72 | - |

| [cm-1] | [cm-1] [a] | |

|---|---|---|

| 1-OH | 1965, 1886 | 1912 |

| 2-OH | 1910, 1853 | 1872 |

| 3-OH | 1880, 1821 | 1840 |

| 1+ | 1965, 1886 | 1912 |

| 2+ |

2012, 1964[b] 1904, 1848 |

1980 1867 |

| 3+ |

1988, 1940[b] 1878, 1819 |

1956 1839 |

| 1-H | 1965, 1888 | 1914 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).