Submitted:

30 October 2023

Posted:

31 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Self-Organizing Map (SOM)

- The three ESG pillar scores (Environmental, Social, and Governance)—to map the total ESG performance in emerging-market companies.

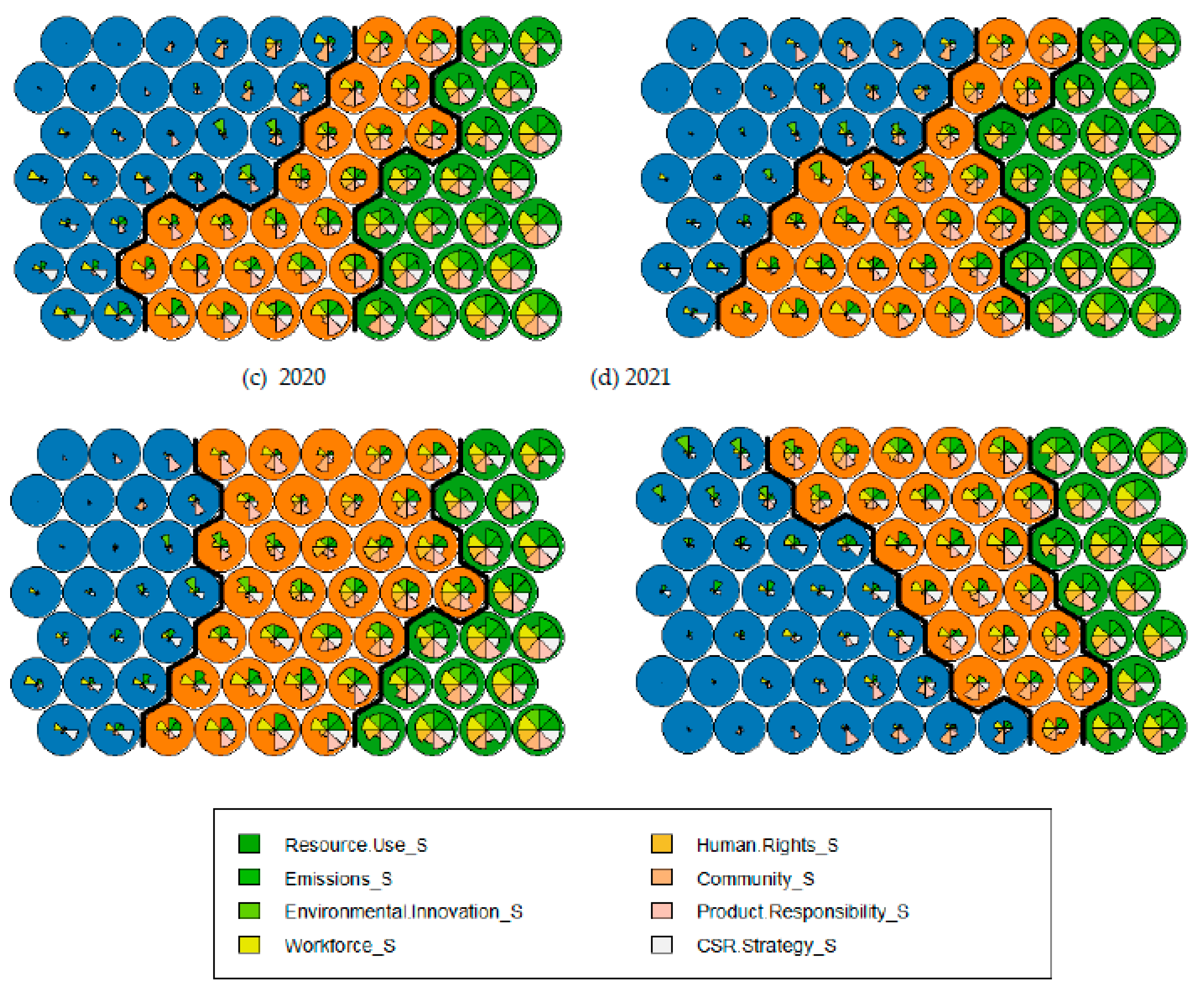

- Eight out of ten TR EIKON ESG themes scores (Resource Use, Emissions, Environmental Innovation, Workforce, Human Rights, Community, Product Responsibility, and CSR Strategy)—to represent theme-based emerging-market ESG behavior.

- A four-folded strategic approach based on and calculated according to the ten TR EIKON ESG themes scores, as presented in Table 3.

- ESG Stakeholder view: highest average score for the ESG component related to employees (ESG.Em_S) and the lowest score on the consumer oriented ESG score (ESG.Cr_S).

- ESG Perspective view: highest average score for the ESG component related to internal issues (ESG.In_S) over external issues (ESG.Ex_S).

- ESG Management Level view: highest average score for the ESG component related to the strategic level (ESG.St_S) over operational (ESG.Op_S) and tactical (ESG.Ta_S) levels.

- ESG Focus view: highest average score for the ESG component related to communication orientation (ESG.Co_S) over technology innovation (ESG.Po_S) and human related (ESG.Ho_S) issues.

3.3. Statistics and Computational details

- Grid size: 10x7.

- Hexagonal topology, Gaussian neighborhood function, Euclidean distance, a standard linearly declining learning rate from 0.1 to 0.01, and 1000 epochs.

- Non-supervised training with PCA (principal component analysis) initialization.

- The number of ideal clusters was obtained by employing two methodologies: WCSS (Within-Cluster Sum of Square) for k-means, and PAM (Partition Around Medoids) clustering, both return the number of three.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Average Silhouette Measure

4.2. Average Silhouette Measure

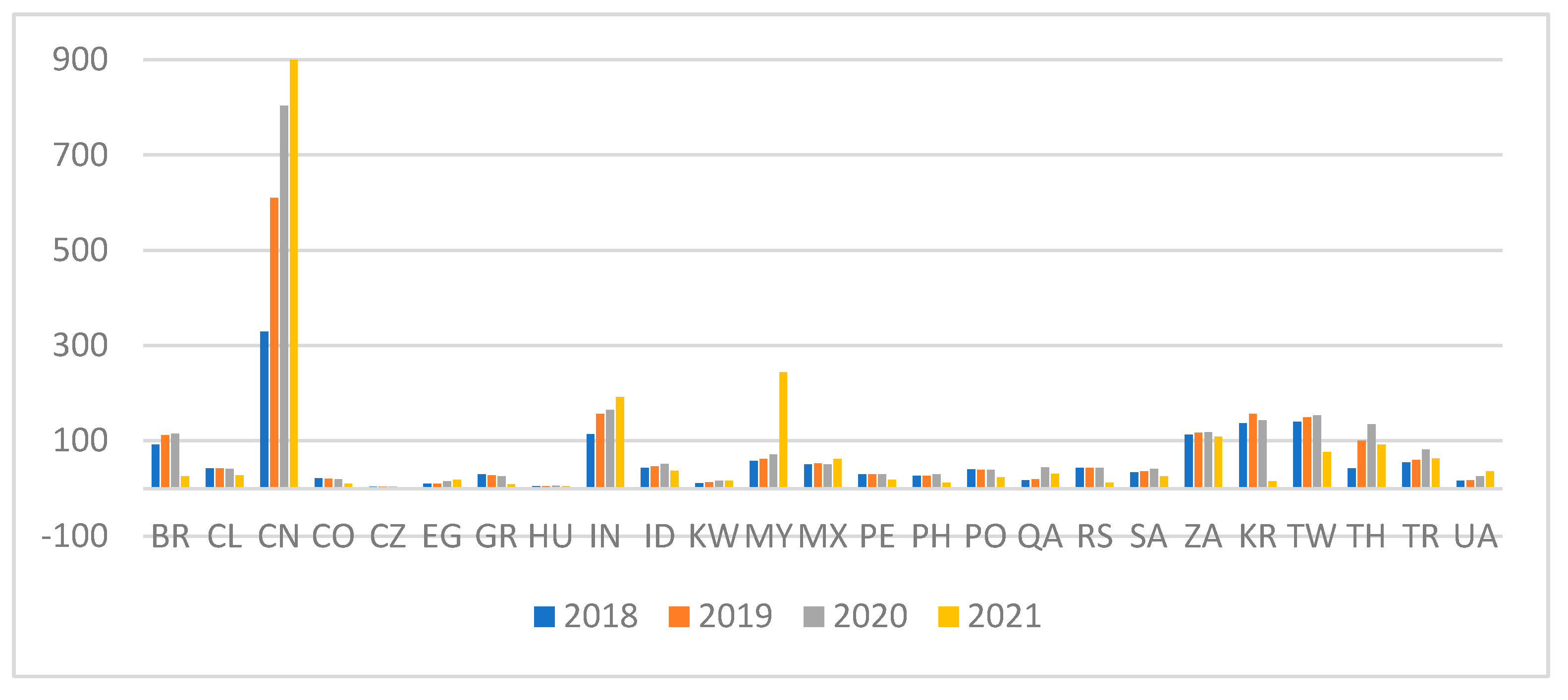

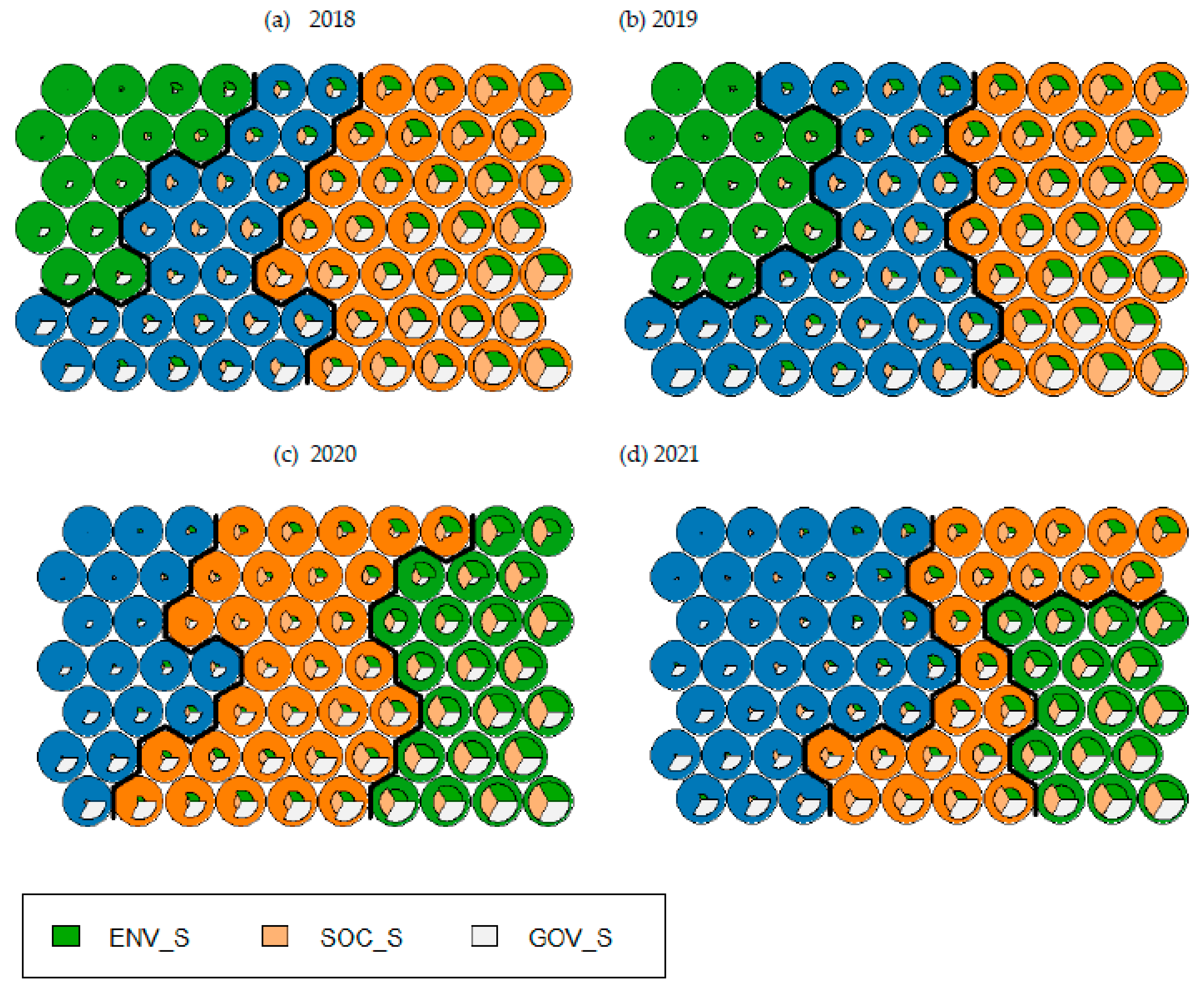

- The percentage of companies included in the Higher ESG cluster decreased yearly during the analysis period. In 2018, there were 18 countries in which the majority of companies fell within the Higher ESG cluster, whereas in 2021, this applied to only eight countries.

- Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Greece, Hungary, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey had the most companies included in the Higher ESG cluster from 2018–2021.

- The percentage of companies included in the Lower ESG cluster increased yearly during the analysis period. In 2018, there were four countries in which the majority of companies fell within the Lower ESG cluster, but, by 2021, this number had fallen to nine countries.

- Qatar was the only country in which the majority of companies fell within the Lower ESG cluster from 2018–2021, which can be explained by the fact that it was only in 2016 that the Qatar Stock Exchange joined the United Nations initiative on sustainable development and thereafter promoted ESG standards.

- Caution is advised when determining the national prevalence of a specific cluster, primarily because of the pronounced differences in the number of investigated companies from each country and certain countries' specificities as regulations.

4.3. Mapping the Thematic ESG Performance for the Emerging-market Companies

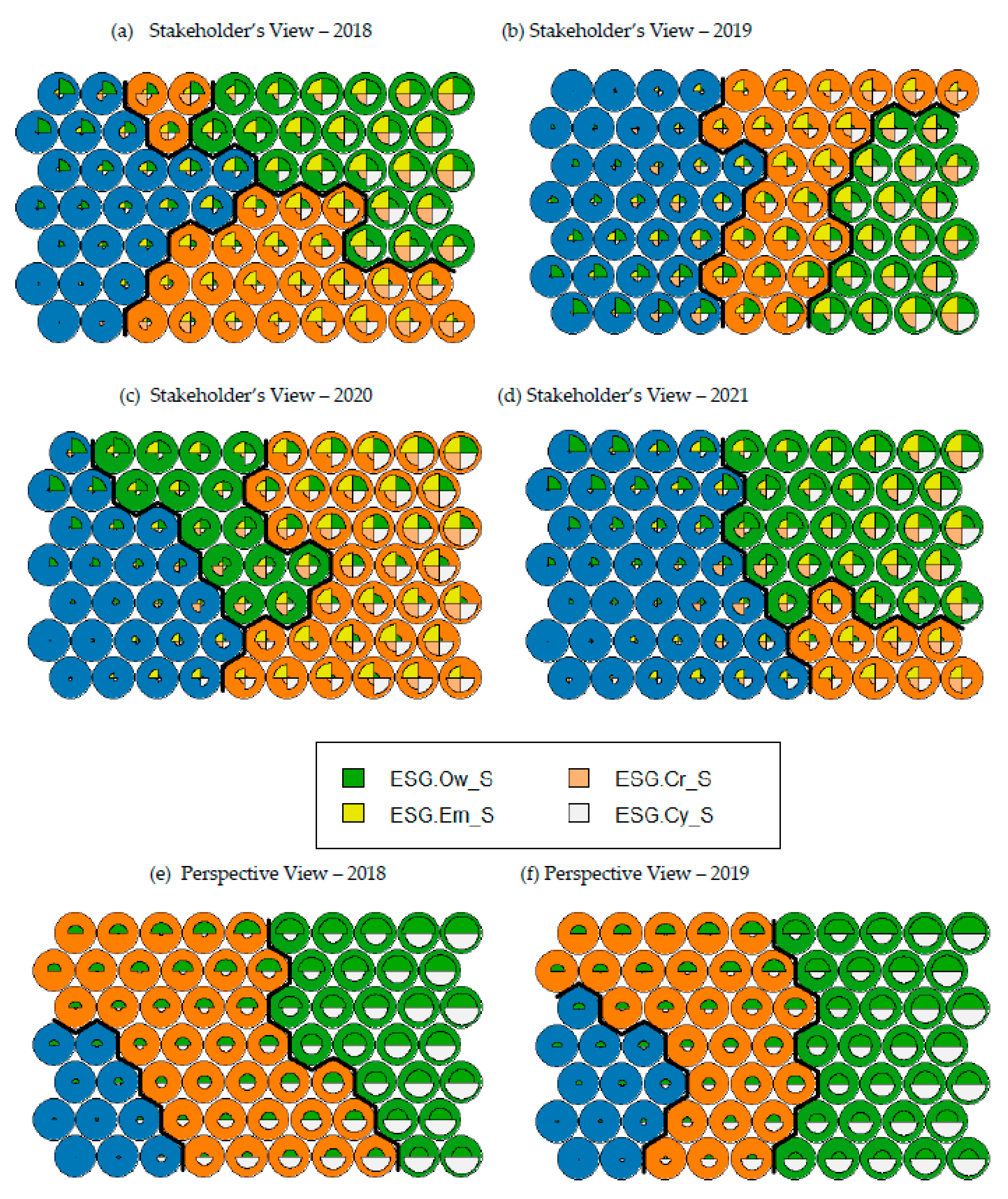

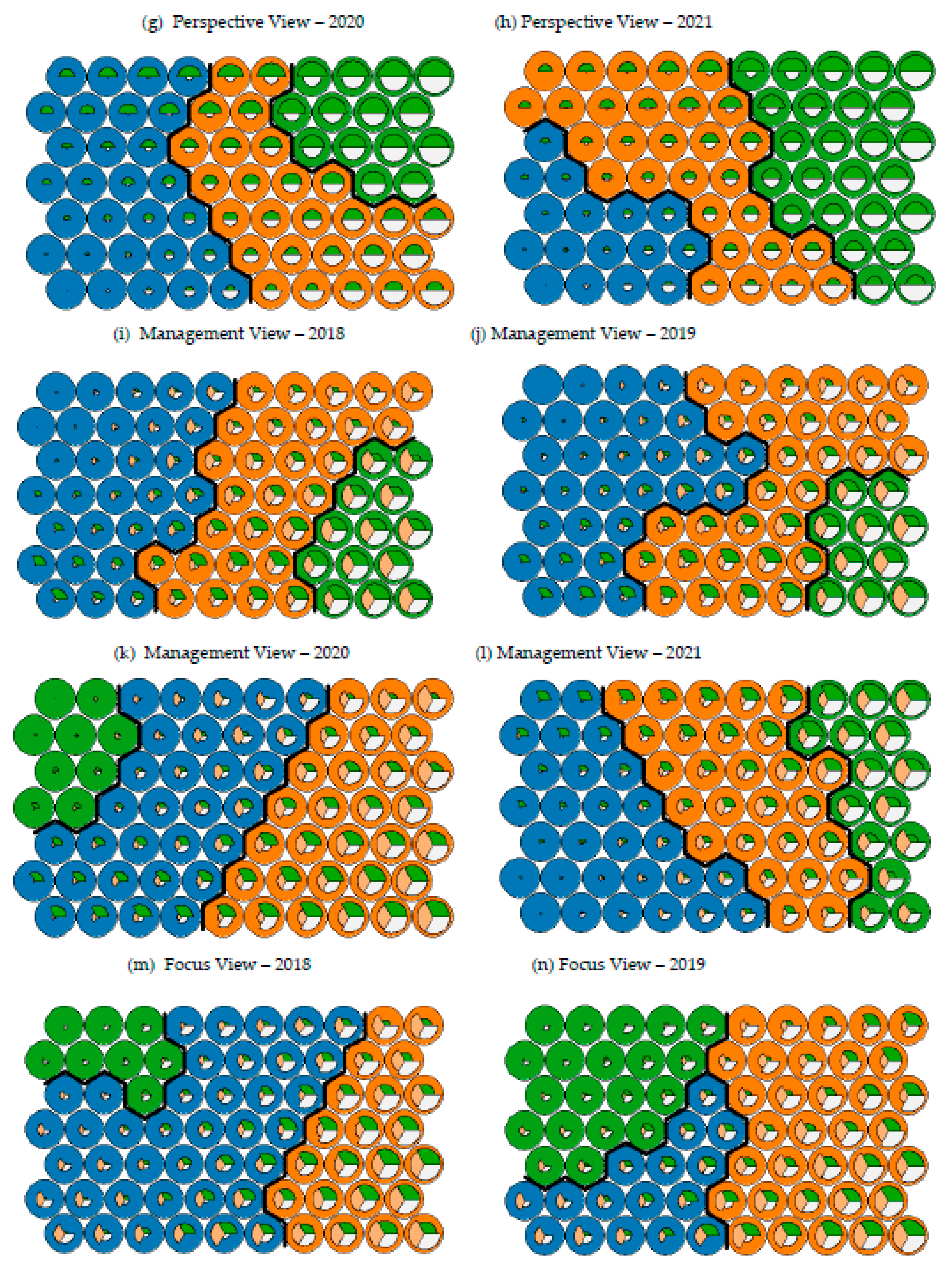

4.4. Mapping the Different Approaches of the ESG Performance for the Emerging-market Companies

- ESG Stakeholder View: The medians within the Middle and Higher ESG clusters show that the sustainability efforts related to employees’ issues receive more attention, which is likely due to an acknowledgment of their decisive role in the organizational results. However, for the lower cluster, the owners-related issues are preferred. Additionally, as the companies shift from lower to middle clusters, less attention is paid to owners-related issues, except for in 2020. These results suggest that it is in fact business (short-term) motivations that guide the companies as opposed to their desire to contribute positively to wider society.

- ESG Perspective View: The medians within each cluster show that emerging-market companies are addressing ESG internal and external issues, which suggests they understand the necessity to address sustainable actions in both directions. However, it is notable that there is a higher level of consideration for the inner-oriented sustainability firm issues than for the outer-oriented issues, especially for the middle and lower clusters.

- ESG Management Level View: Interestingly, the emerging-market companies in the lower and middle clusters addressed more ESG strategic issues than operational and tactical issues, suggesting that they are trying to improve their sustainable behavior by concentrating on long-term sustainability matters. However, in the higher cluster, the companies are more focused on operational issues yet remain interested in long-term strategic sustainability issues due to integrated competitive reasons.

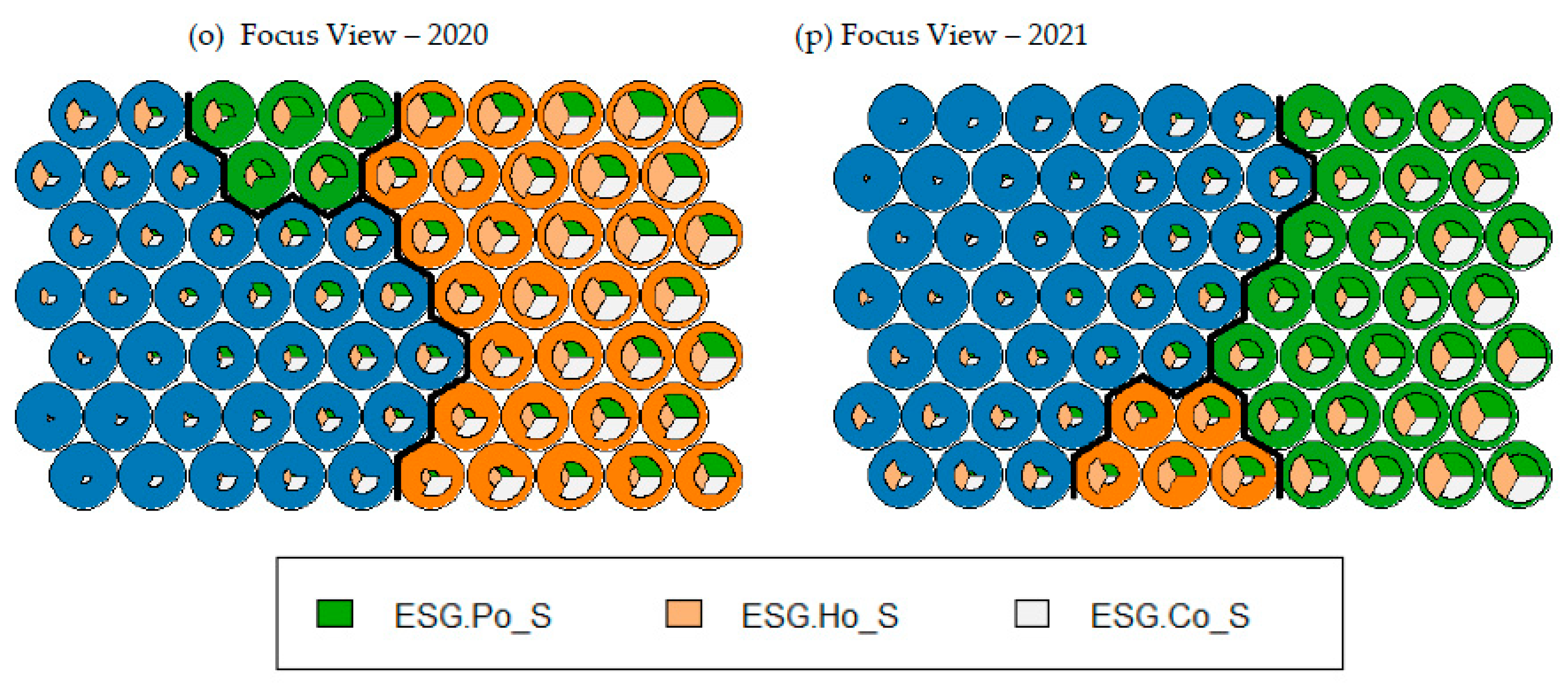

- ESG Focus View: Overall, companies prefer to concentrate on sustainable communication-related issues in order to enhance their image through ESG involvement. The hierarchy within clusters between these three pillars is the same. The sustainable-oriented process is situated in the last position, suggesting that the sample companies do not concentrate their efforts or have difficulties implementing sustainable technologies and innovations.

- From a Stakeholder’s View, between 2018 and 2020, the Community (ESG.Cy_S)-related issues differ the most across the three clusters, while Owners (ESG.Ow_S)-related topics are the most similar. This indicates that better ESG performers’ sustainable corporate behaviors were more guided by societal reasons than by purely business-based motivations, corroborating the idea that for an organization to be sustainable, it must adopt a strategy to generate a competitive advantage that is in line with societal expectations [40,41]. However, by 2021, this behavior had scarcely changed, and, despite the highest corporate sustainable contribution still being dedicated to Community (ESG.Cy_S)-related issues, more attention was focused on Owners (ESG.Ow_S)-related issues in the Higher ESG cluster, which may be due to the urge to protect shareholders and the company during the COVID-19 pandemic. These results corroborate [45] findings and indicate that the sample companies also considered stakeholders to be as crucial as their shareholders, even during periods of global crisis.

- From a Perspective View, the ESG internal-oriented (ESG.In_S) impact more effectively discriminates the sustainable corporate behaviors of the emerging-market companies. Integrating ESG in companies’ internal policies and operating practices may increase their competitiveness and enhance their economic and social performance [42,43]. This result is exactly the opposite of that found for the European companies in Iamandi et al.’s [6] research.

- From a Management View, ESG Operational (ESG.Op_S) and ESG Tactical (ESG.Ta_S) issues differ the most across the three clusters, indicating that companies with higher sustainable behavior prefer to concentrate on these topics in order to increase organizational efficiency and competitiveness. In contrast, European companies prefer to focus on ESG Strategic level (ESG.St_S).

- From a Focus View, the communication (ESG.Co_S) orientation variable differs the most across the three clusters during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that preserving and projecting a good organizational image for companies in the Higher ESG cluster was a priority over process-oriented and human-oriented issues.

5. Final Thoughts

Acknowledgments and Funding

Conflicts of Interest

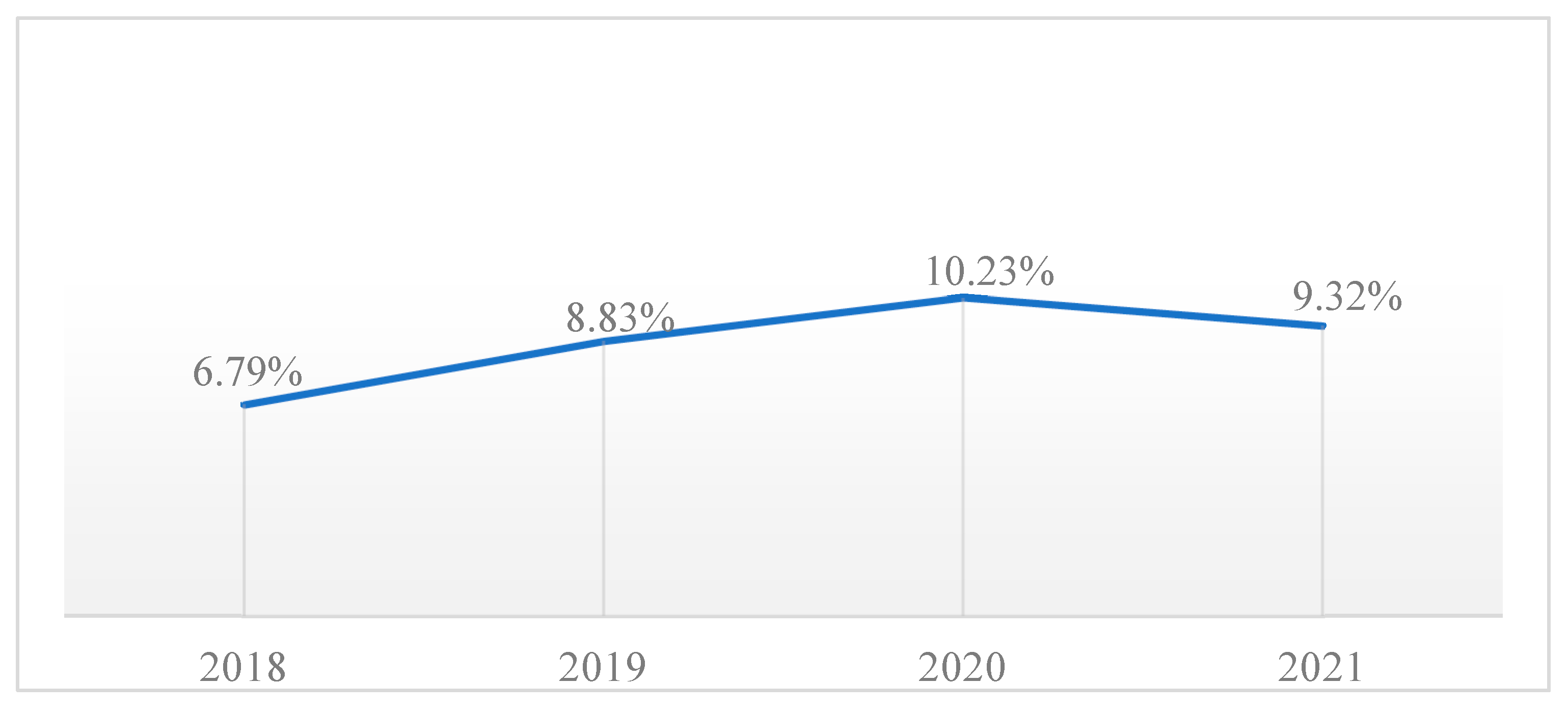

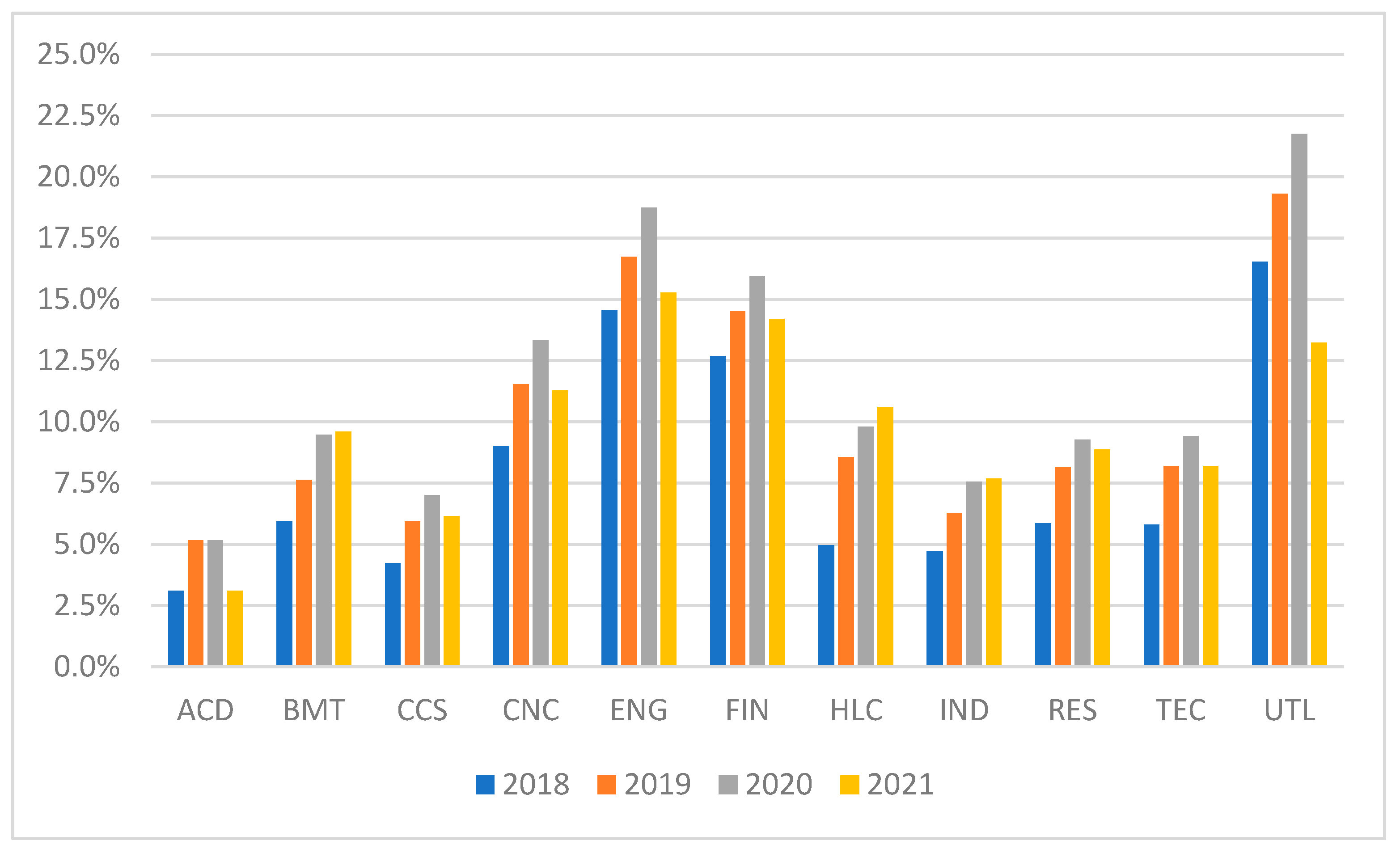

Appendix I – Sectoral analysis of the ESG reporting degree.

| Year | Indicator | Economic Sector | |||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOTAL | ||

| 2018 | No. of ESG reporting companies | 3 | 184 | 153 | 154 | 80 | 298 | 73 | 193 | 74 | 189 | 95 | 1,499 |

| No. of total listed companies | 97 | 3,093 | 3,625 | 1,710 | 550 | 2,352 | 1,471 | 4,093 | 1,262 | 3,262 | 575 | 22,090 | |

|

% of ESG reporting companies in total companies |

3.09 | 5.95 | 4.22 | 9.00 | 14.54 | 12.67 | 4.96 | 4.72 | 5.86 | 5.79 | 16.52 | 6.79 | |

| 2019 | No. of ESG reporting companies | 5 | 236 | 215 | 197 | 92 | 341 | 126 | 257 | 103 | 267 | 111 | 1,950 |

| No. of total listed companies | 97 | 3,093 | 3,625 | 1,710 | 550 | 2,352 | 1,471 | 4,093 | 1,262 | 3,262 | 575 | 22,090 | |

|

% of ESG reporting companies in total companies |

5.15 | 7.63 | 5.93 | 11.52 | 16.73 | 14.50 | 8.56 | 6.28 | 8.16 | 8.18 | 19.30 | 8.83 | |

| 2020 | No. of ESG reporting companies | 5 | 293 | 254 | 228 | 103 | 375 | 144 | 309 | 117 | 307 | 125 | 2,260 |

| No. of total listed companies | 97 | 3,093 | 3,625 | 1,710 | 550 | 2,352 | 1,471 | 4,093 | 1,262 | 3,262 | 575 | 22,090 | |

|

% of ESG reporting companies in total companies |

5.15 | 9.47 | 7.01 | 13.33 | 18.73 | 15.94 | 9.79 | 7.55 | 9.27 | 9.41 | 21.74 | 10.23 | |

| 2021 | No. of ESG reporting companies | 3 | 297 | 223 | 193 | 84 | 334 | 156 | 314 | 112 | 267 | 76 | 2,059 |

| No. of total listed companies | 97 | 3,093 | 3,625 | 1,710 | 550 | 2,352 | 1,471 | 4,093 | 1,262 | 3,262 | 575 | 22,090 | |

|

% of ESG reporting companies in total companies |

3.09 | 9.60 | 6.15 | 11.28 | 15.27 | 14.20 | 10.60 | 7.67 | 8.87 | 8.19 | 13.22 | 9.32 | |

Appendix II - Number of sample companies by economic sector and country.

| 2018 | |||||||||||||

| Country | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOTAL | % | |

| BR | 2 | 11 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 14 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 16 | 92 | 6.14 |

| CL | - | 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 7 | - | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 42 | 2.80 |

| CN | - | 34 | 34 | 16 | 14 | 66 | 29 | 65 | 13 | 42 | 16 | 329 | 21.95 |

| CO | - | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | 8 | - | 2 | - | 1 | 4 | 21 | 1.40 |

| CZ* | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 0.20 |

| EG | - | 2 | - | 1 | - | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 10 | 0.67 |

| GR* | - | - | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 | - | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 29 | 1.93 |

| HU* | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 0.33 |

| IN | - | 18 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 22 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 114 | 7.61 |

| ID | - | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 43 | 2.87 |

| KW | - | - | - | ‘ | - | 5 | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 11 | 0.73 |

| MY | - | 4 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 58 | 3.87 |

| MX | - | 9 | 7 | 12 | - | 10 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 1 | - | 50 | 3.34 |

| PE | - | 12 | 1 | 5 | - | 5 | - | 3 | - | - | 4 | 30 | 2.00 |

| PH | - | - | 2 | 7 | - | 4 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 26 | 1.73 |

| PO* | - | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 12 | - | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 40 | 2.67 |

| QA | - | 1 | - | 1 | 3 | 7 | - | - | 2 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 1.13 |

| RS* | - | 13 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 6 | - | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 43 | 2.87 |

| SA | - | 10 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 1 | - | 2 | 2 | 1 | 34 | 2.27 |

| ZA | 1 | 23 | 13 | 18 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 9 | - | 113 | 7.54 |

| KR | - | 12 | 20 | 19 | 5 | 20 | 11 | 27 | - | 20 | 3 | 137 | 9.14 |

| TW | - | 12 | 20 | 5 | 1 | 17 | 3 | 19 | 2 | 61 | - | 140 | 9.34 |

| TH | - | 2 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 42 | 2.80 |

| TR | - | 5 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 54 | 3.60 |

| UA | - | - | - | 1 | - | 9 | - | 1 | 3 | 2 | - | 16 | 1.07 |

| TOTAL | 3 | 184 | 151 | 154 | 80 | 293 | 70 | 187 | 73 | 187 | 94 | 1,499 | 100 |

| 2019 | |||||||||||||

| Country | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOTAL | % | |

| BR | 3 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 15 | 5 | 13 | 12 | 4 | 16 | 112 | 5.74 |

| CL | - | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 7 | - | 5 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 42 | 2.15 |

| CN | 1 | 75 | 57 | 44 | 21 | 81 | 70 | 111 | 26 | 104 | 20 | 610 | 31.28 |

| CO | - | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | 8 | - | 2 | - | 1 | 3 | 20 | 1.03 |

| CZ* | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 0.15 |

| EG | - | 2 | - | 1 | - | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 10 | 0.51 |

| GR* | - | - | 3 | 2 | 2 | 8 | - | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 27 | 1.38 |

| HU* | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 0.26 |

| IN | - | 22 | 21 | 12 | 9 | 33 | 14 | 16 | 7 | 13 | 9 | 156 | 8.00 |

| ID | - | 8 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 46 | 2.36 |

| KW | - | - | - | 1 | - | 7 | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 13 | 0.67 |

| MY | - | 3 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 62 | 3.18 |

| MX | - | 9 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 1 | - | 52 | 2.67 |

| PE | - | 12 | 1 | 5 | - | 5 | - | 3 | - | - | 4 | 30 | 1.54 |

| PH | - | - | 2 | 7 | - | 4 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 26 | 1.33 |

| PO* | - | 6 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 12 | - | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 39 | 2.00 |

| QA | - | 1 | - | 2 | 3 | 8 | - | - | 2 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 0.97 |

| RS* | - | 13 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 6 | - | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 43 | 2.21 |

| SA | - | 10 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 36 | 1.85 |

| ZA | 1 | 22 | 17 | 19 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 9 | - | 117 | 6.00 |

| KR | - | 14 | 25 | 20 | 4 | 23 | 14 | 30 | - | 23 | 3 | 156 | 8.00 |

| TW | - | 12 | 20 | 4 | 1 | 18 | 4 | 20 | 2 | 68 | - | 149 | 7.64 |

| TH | - | 4 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 16 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 15 | 100 | 5.13 |

| TR | - | 6 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 60 | 3.08 |

| UA | - | - | - | 1 | - | 10 | - | 1 | 3 | 2 | - | 17 | 0.87 |

| TOTAL | 5 | 232 | 213 | 197 | 92 | 335 | 123 | 251 | 100 | 265 | 110 | 1,950 | 100 |

| 2020 | |||||||||||||

| Country | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOTAL | % | |

| BR | 2 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 13 | 12 | 4 | 17 | 115 | 5.09 |

| CL | - | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | - | 5 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 41 | 1.81 |

| CN | 1 | 115 | 83 | 57 | 27 | 93 | 84 | 153 | 30 | 132 | 28 | 803 | 35.53 |

| CO | - | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | 8 | - | 2 | - | 1 | 2 | 19 | 0.84 |

| CZ* | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 0.13 |

| EG | - | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | - | 1 | 3 | 2 | - | 15 | 0.66 |

| GR* | - | - | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | - | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 25 | 1.11 |

| HU* | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | 6 | 0.27 |

| IN | - | 23 | 23 | 13 | 9 | 34 | 14 | 16 | 6 | 16 | 11 | 165 | 7.30 |

| ID | - | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 51 | 2.26 |

| KW | - | - | - | 1 | - | 9 | - | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | 16 | 0.71 |

| MY | - | 7 | 10 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 71 | 3.14 |

| MX | - | 8 | 7 | 12 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 1 | - | 50 | 2.21 |

| PE | - | 12 | 1 | 5 | - | 4 | - | 3 | - | - | 4 | 29 | 1.28 |

| PH | - | - | 3 | 8 | - | 4 | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 29 | 1.28 |

| PO* | - | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 12 | - | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 39 | 1.73 |

| QA | - | 4 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 44 | 1.95 |

| RS* | - | 13 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 6 | - | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 43 | 1.90 |

| SA | - | 11 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 41 | 1.81 |

| ZA | 1 | 22 | 17 | 19 | 1 | 21 | 4 | 11 | 13 | 9 | - | 118 | 5.22 |

| KR | - | 14 | 21 | 17 | 3 | 23 | 11 | 28 | - | 23 | 3 | 143 | 6.33 |

| TW | - | 13 | 21 | 4 | 1 | 18 | 5 | 20 | 2 | 69 | - | 153 | 6.77 |

| TH | - | 7 | 21 | 16 | 12 | 22 | 6 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 15 | 135 | 5.97 |

| TR | - | 10 | 13 | 12 | 3 | 19 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 81 | 3.58 |

| UA | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 14 | - | 2 | 3 | 2 | - | 25 | 1.11 |

| TOTAL | 5 | 289 | 252 | 227 | 103 | 369 | 140 | 302 | 114 | 305 | 124 | 2,260 | 100 |

| 2021 | |||||||||||||

| Country | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOTAL | % | |

| BR | - | 3 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 25 | 1.21 |

| CL | - | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | - | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 27 | 1.31 |

| CN | 1 | 139 | 87 | 66 | 33 | 102 | 98 | 170 | 37 | 141 | 26 | 900 | 43.71 |

| CO | - | 1 | - | 2 | 1 | 4 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 10 | 0.49 |

| CZ* | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0.10 |

| EG | 1 | - | 3 | 3 | - | 4 | 3 | - | 3 | 1 | - | 18 | 0.87 |

| GR* | - | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 9 | 0.44 |

| HU* | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 5 | 0.24 |

| IN | - | 26 | 26 | 13 | 8 | 42 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 18 | 14 | 192 | 9.32 |

| ID | - | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 18 | - | - | 3 | 3 | - | 37 | 1.80 |

| KW | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 9 | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | - | 16 | 0.78 |

| MY | - | 36 | 28 | 30 | 13 | 16 | 12 | 54 | 26 | 25 | 4 | 244 | 11.85 |

| MX | - | 11 | 13 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 2 | - | 62 | 3.01 |

| PE | - | 8 | 1 | 1 | - | 3 | - | 3 | - | - | 2 | 18 | 0.87 |

| PH | - | - | 2 | 2 | - | 5 | - | - | - | 1 | 2 | 12 | 0.58 |

| PO* | - | 4 | 2 | 1 | - | 8 | - | - | 1 | 5 | 2 | 23 | 1.12 |

| QA | - | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 31 | 1.51 |

| RS* | - | 7 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 12 | 0.58 |

| SA | - | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | - | 25 | 1.21 |

| ZA | 1 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 1 | 19 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 9 | - | 109 | 5.29 |

| KR | - | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | - | 1 | - | 15 | 0.73 |

| TW | - | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 10 | - | 40 | - | 76 | 3.69 |

| TH | - | 10 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 12 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 92 | 4.47 |

| TR | - | 8 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 17 | - | 8 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 63 | 3.06 |

| UA | - | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 19 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 36 | 1.75 |

| TOTAL | 3 | 294 | 221 | 192 | 84 | 325 | 152 | 308 | 110 | 265 | 75 | 2,059 | 100 |

Appendix III – Descriptive Statistics of 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021.

| 2018 | |||||||||

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | 25th Q | Median | 75th Q | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

| ENV_S | 0.00 | 97.52 | 38.10 | 13.98 | 37.83 | 59.88 | 26.99 | 0.17 | -1.11 |

| SOC_S | 0.31 | 97.15 | 45.22 | 22.68 | 45.44 | 66.66 | 25.79 | -0.01 | -1.11 |

| GOV_S | 0.32 | 98.72 | 48.17 | 30.57 | 48.69 | 65.93 | 22.33 | -0.06 | -0.90 |

| ESG_S | 0.66 | 92.27 | 44.71 | 28.73 | 45.55 | 61.06 | 21.18 | -0.06 | -0.82 |

| ESG.Combined_S | 0.66 | 89.35 | 43.92 | 28.61 | 44.21 | 59.73 | 20.73 | -0.04 | -0.78 |

| ESG.Controversies_S | 1.32 | 100.00 | 95.26 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 16.67 | -3.82 | 14.26 |

| Resource.Use_S | 0.00 | 99.75 | 42.02 | 12.58 | 40.92 | 69.33 | 31.29 | 0.14 | -1.27 |

| Emissions_S | 0.00 | 99.83 | 44.25 | 14.71 | 45.74 | 72.10 | 31.79 | 0.02 | -1.30 |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.00 | 99.69 | 24.58 | 0.00 | 2.72 | 50.00 | 30.07 | 0.84 | -0.69 |

| Workforce_S | 0.24 | 99.80 | 56.67 | 33.33 | 61.43 | 81.38 | 29.27 | -0.36 | -1.02 |

| Human.Rights_S | 0.00 | 98.20 | 30.73 | 0.00 | 19.81 | 59.91 | 32.84 | 0.61 | -1.11 |

| Community_S | 0.70 | 99.86 | 45.39 | 15.11 | 40.13 | 76.75 | 31.99 | 0.22 | -1.44 |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.00 | 99.93 | 46.71 | 16.78 | 46.67 | 77.44 | 33.36 | -0.05 | -1.33 |

| Management_S | 0.02 | 99.64 | 48.78 | 24.10 | 48.93 | 72.90 | 28.51 | 0.02 | -1.19 |

| Shareholders_S | 0.13 | 99.87 | 49.70 | 24.69 | 50.00 | 74.82 | 28.83 | 0.01 | -1.20 |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.00 | 99.54 | 42.85 | 11.59 | 43.02 | 71.74 | 32.08 | 0.11 | -1.33 |

| ESG.Ow_S | 0.40 | 98.73 | 49.02 | 30.76 | 49.87 | 67.75 | 23.66 | -0.03 | -0.93 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.24 | 99.80 | 56.67 | 33.33 | 61.43 | 81.38 | 29.27 | -0.36 | -1.02 |

| ESG.Cr_S | 0.00 | 96.26 | 33.15 | 11.84 | 29.52 | 53.10 | 25.96 | 0.46 | -0.83 |

| ESG.Cy_S | 0.20 | 96.26 | 42.19 | 18.69 | 42.51 | 64.35 | 26.84 | 0.05 | -1.17 |

| ESG.S_S | 0.88 | 91.88 | 44.74 | 29.60 | 45.38 | 60.88 | 20.86 | -0.10 | -0.81 |

| ESG.In_S | 1.42 | 96.29 | 51.10 | 37.60 | 51.94 | 67.27 | 20.75 | -0.30 | -0.52 |

| ESG.Ex_S | 0.15 | 94.88 | 39.19 | 18.35 | 39.19 | 58.60 | 24.55 | 0.12 | -1.05 |

| ESG.P_S | 0.88 | 91.88 | 44.74 | 29.60 | 45.38 | 60.88 | 20.86 | -0.10 | -0.81 |

| ESG.St_S | 0.65 | 98.31 | 47.08 | 29.32 | 47.00 | 65.63 | 23.39 | 0.00 | -0.86 |

| ESG.Ta_S | 0.94 | 93.66 | 45.11 | 29.94 | 46.39 | 60.79 | 21.04 | -0.08 | -0.68 |

| ESG.Op_S | 0.00 | 97.43 | 42.26 | 17.90 | 43.32 | 64.67 | 27.55 | 0.05 | -1.19 |

| ESG.ML_S | 0.88 | 91.88 | 44.74 | 29.60 | 45.38 | 60.88 | 20.86 | -0.10 | -0.81 |

| ESG.Po_S | 0.00 | 96.39 | 38.92 | 16.35 | 38.47 | 58.49 | 25.40 | 0.13 | -1.05 |

| ESG.Ho_S | 1.42 | 97.80 | 49.93 | 36.35 | 50.64 | 65.73 | 20.70 | -0.20 | -0.53 |

| ESG.Co_S | 1.72 | 98.95 | 70.42 | 59.02 | 70.15 | 81.80 | 14.38 | -0.18 | -0.22 |

| ESG.F_S | 3.21 | 89.84 | 50.52 | 37.23 | 50.93 | 64.93 | 18.27 | -0.09 | -0.80 |

| 2019 | |||||||||

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | 25th Q | Median | 75th Q | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

| ENV_S | 0.00 | 97.26 | 36.80 | 12.72 | 34.64 | 58.47 | 26.84 | 0.25 | -1.08 |

| SOC_S | 0.34 | 97.20 | 43.47 | 20.46 | 43.22 | 64.70 | 25.90 | 0.10 | -1.12 |

| GOV_S | 0.16 | 97.62 | 48.42 | 30.23 | 48.49 | 66.59 | 22.14 | -0.04 | -0.94 |

| ESG_S | 0.72 | 94.30 | 43.60 | 26.97 | 42.82 | 59.63 | 20.91 | 0.09 | -0.86 |

| ESG.Combined_S | 0.72 | 94.30 | 42.76 | 26.76 | 41.79 | 57.74 | 20.34 | 0.11 | -0.81 |

| ESG.Controversies_S | 0.77 | 100.00 | 95.44 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 16.51 | -3.92 | 14.86 |

| Resource.Use_S | 0.00 | 99.85 | 40.49 | 10.18 | 38.58 | 66.77 | 31.23 | 0.21 | -1.25 |

| Emissions_S | 0.00 | 99.86 | 42.30 | 12.52 | 40.90 | 70.30 | 31.72 | 0.12 | -1.28 |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.00 | 99.72 | 24.28 | 0.00 | 3.79 | 50.00 | 29.61 | 0.85 | -0.64 |

| Workforce_S | 0.20 | 99.90 | 54.68 | 30.84 | 57.36 | 80.13 | 29.14 | -0.23 | -1.12 |

| Human.Rights_S | 0.00 | 98.20 | 29.60 | 0.00 | 17.57 | 56.67 | 32.22 | 0.67 | -1.01 |

| Community_S | 0.53 | 99.88 | 43.56 | 14.55 | 35.06 | 74.12 | 31.71 | 0.31 | -1.40 |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.00 | 99.93 | 45.42 | 15.48 | 45.49 | 75.75 | 33.05 | 0.02 | -1.32 |

| Management_S | 0.02 | 99.78 | 48.85 | 24.22 | 48.73 | 73.08 | 28.56 | 0.03 | -1.19 |

| Shareholders_S | 0.32 | 99.93 | 50.40 | 25.25 | 50.52 | 75.34 | 28.89 | -0.02 | -1.21 |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.00 | 99.74 | 43.34 | 13.54 | 43.84 | 72.09 | 31.68 | 0.11 | -1.29 |

| ESG.Ow_S | 0.19 | 98.56 | 49.25 | 29.80 | 49.51 | 68.76 | 23.69 | -0.03 | -0.99 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.20 | 99.90 | 54.68 | 30.84 | 57.36 | 80.13 | 29.14 | -0.23 | -1.12 |

| ESG.Cr_S | 0.00 | 98.17 | 32.47 | 12.13 | 28.23 | 52.55 | 25.56 | 0.50 | -0.78 |

| ESG.Cy_S | 0.18 | 96.20 | 40.75 | 16.76 | 40.10 | 62.78 | 26.87 | 0.15 | -1.17 |

| ESG.S_S | 1.02 | 93.80 | 43.77 | 27.45 | 43.25 | 59.16 | 20.55 | 0.06 | -0.85 |

| ESG.In_S | 1.18 | 95.08 | 50.58 | 36.30 | 51.20 | 66.21 | 20.24 | -0.16 | -0.57 |

| ESG.Ex_S | 0.14 | 95.36 | 37.83 | 15.78 | 36.29 | 57.88 | 24.59 | 0.21 | -1.06 |

| ESG.P_S | 1.02 | 93.80 | 43.77 | 27.45 | 43.25 | 59.16 | 20.55 | 0.06 | -0.85 |

| ESG.St_S | 0.49 | 97.92 | 46.74 | 28.64 | 46.20 | 64.25 | 22.75 | 0.07 | -0.85 |

| ESG.Ta_S | 0.73 | 97.65 | 44.20 | 28.53 | 44.16 | 59.01 | 20.72 | 0.08 | -0.70 |

| ESG.Op_S | 0.00 | 95.93 | 40.68 | 15.41 | 39.75 | 63.53 | 27.57 | 0.14 | -1.19 |

| ESG.ML_S | 1.02 | 93.80 | 43.77 | 27.45 | 43.25 | 59.16 | 20.55 | 0.06 | -0.85 |

| ESG.Po_S | 0.00 | 96.37 | 37.63 | 15.02 | 36.84 | 57.89 | 25.32 | 0.21 | -1.04 |

| ESG.Ho_S | 1.18 | 97.79 | 49.26 | 35.06 | 49.18 | 64.32 | 20.25 | -0.06 | -0.58 |

| ESG.Co_S | 14.25 | 99.41 | 70.04 | 59.10 | 69.22 | 81.15 | 13.95 | -0.07 | -0.31 |

| ESG.F_S | 12.34 | 94.51 | 49.69 | 35.45 | 49.14 | 63.21 | 17.91 | 0.07 | -0.84 |

| 2020 | |||||||||

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | 25th Q | Median | 75th Q | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

| ENV_S | 0.00 | 98.28 | 38.23 | 14.64 | 36.14 | 60.26 | 26.99 | 0.21 | -1.09 |

| SOC_S | 0.35 | 98.36 | 44.40 | 21.29 | 44.00 | 66.11 | 25.93 | 0.09 | -1.15 |

| GOV_S | 0.56 | 95.44 | 49.56 | 32.38 | 49.74 | 67.36 | 21.70 | -0.04 | -0.95 |

| ESG_S | 1.27 | 93.60 | 44.68 | 28.04 | 44.29 | 60.99 | 20.78 | 0.05 | -0.90 |

| ESG.Combined_S | 1.27 | 92.79 | 43.79 | 27.96 | 43.18 | 59.24 | 20.13 | 0.07 | -0.83 |

| ESG.Controversies_S | 0.98 | 100.00 | 94.76 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 16.74 | -3.51 | 11.96 |

| Resource.Use_S | 0.00 | 99.87 | 42.11 | 11.80 | 40.96 | 69.31 | 31.57 | 0.14 | -1.29 |

| Emissions_S | 0.00 | 99.89 | 43.77 | 16.09 | 42.74 | 71.09 | 31.45 | 0.08 | -1.26 |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.00 | 99.76 | 25.80 | 0.00 | 7.48 | 50.00 | 30.55 | 0.78 | -0.78 |

| Workforce_S | 0.24 | 99.93 | 54.70 | 30.12 | 57.33 | 80.72 | 29.24 | -0.20 | -1.17 |

| Human.Rights_S | 0.00 | 97.50 | 30.75 | 0.00 | 18.26 | 59.48 | 32.50 | 0.62 | -1.09 |

| Community_S | 0.00 | 99.94 | 44.79 | 17.26 | 37.37 | 74.08 | 30.72 | 0.30 | -1.35 |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.00 | 99.94 | 47.36 | 20.42 | 46.12 | 76.62 | 32.54 | -0.02 | -1.29 |

| Management_S | 0.27 | 99.71 | 50.07 | 25.70 | 50.00 | 74.43 | 28.35 | 0.00 | -1.19 |

| Shareholders_S | 0.05 | 99.95 | 51.22 | 26.66 | 52.03 | 75.72 | 28.52 | -0.03 | -1.20 |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.00 | 99.94 | 44.58 | 15.99 | 43.06 | 72.83 | 31.19 | 0.08 | -1.28 |

| ESG.Ow_S | 0.69 | 97.66 | 50.37 | 31.14 | 50.60 | 69.21 | 23.13 | -0.04 | -0.96 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.24 | 99.93 | 54.70 | 30.12 | 57.33 | 80.72 | 29.24 | -0.20 | -1.17 |

| ESG.Cr_S | 0.00 | 97.66 | 34.15 | 12.57 | 30.34 | 54.15 | 25.78 | 0.47 | -0.80 |

| ESG.Cy_S | 0.00 | 96.65 | 42.15 | 18.09 | 41.97 | 64.42 | 26.82 | 0.10 | -1.19 |

| ESG.S_S | 1.68 | 94.08 | 44.93 | 28.50 | 44.87 | 61.18 | 20.48 | 0.03 | -0.89 |

| ESG.In_S | 2.18 | 94.99 | 51.32 | 36.72 | 51.66 | 66.59 | 19.94 | -0.14 | -0.65 |

| ESG.Ex_S | 0.00 | 98.05 | 39.34 | 17.73 | 38.90 | 58.76 | 24.61 | 0.18 | -1.04 |

| ESG.P_S | 1.68 | 94.08 | 44.93 | 28.50 | 44.87 | 61.18 | 20.48 | 0.03 | -0.89 |

| ESG.St_S | 0.62 | 98.39 | 47.97 | 29.86 | 47.85 | 65.19 | 22.34 | 0.00 | -0.90 |

| ESG.Ta_S | 1.06 | 96.21 | 44.85 | 28.49 | 44.36 | 60.01 | 20.89 | 0.10 | -0.74 |

| ESG.Op_S | 0.00 | 98.29 | 42.25 | 16.98 | 41.57 | 65.26 | 27.53 | 0.09 | -1.19 |

| ESG.ML_S | 1.68 | 94.08 | 44.93 | 28.50 | 44.87 | 61.18 | 20.48 | 0.03 | -0.89 |

| ESG.Po_S | 0.00 | 98.10 | 39.23 | 17.60 | 39.13 | 59.19 | 25.38 | 0.17 | -1.02 |

| ESG.Ho_S | 2.18 | 97.30 | 49.99 | 35.37 | 49.73 | 64.85 | 19.99 | -0.05 | -0.65 |

| ESG.Co_S | 18.66 | 99.40 | 70.29 | 59.77 | 69.59 | 80.70 | 13.54 | 0.00 | -0.48 |

| ESG.F_S | 8.11 | 94.76 | 50.63 | 36.56 | 50.80 | 64.52 | 17.78 | 0.03 | -0.85 |

| 2021 | |||||||||

| Variable | Min | Max | Mean | 25th Q | Median | 75th Q | SD | Skew | Kurtosis |

| ENV_S | 0.00 | 98.76 | 37.02 | 14.76 | 34.11 | 57.48 | 25.94 | 0.30 | -0.97 |

| SOC_S | 0.75 | 98.67 | 42.60 | 21.19 | 40.04 | 62.08 | 24.91 | 0.27 | -0.99 |

| GOV_S | 1.01 | 95.77 | 50.98 | 34.10 | 50.99 | 68.32 | 21.12 | -0.06 | -0.98 |

| ESG_S | 2.59 | 91.88 | 43.91 | 28.15 | 42.67 | 58.26 | 19.65 | 0.21 | -0.80 |

| ESG.Combined_S | 2.59 | 91.88 | 43.36 | 28.02 | 42.06 | 57.21 | 19.21 | 0.22 | -0.75 |

| ESG.Controversies_S | 0.83 | 100.00 | 97.09 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 12.99 | -5.02 | 26.00 |

| Resource.Use_S | 0.00 | 99.88 | 41.01 | 12.35 | 38.92 | 67.11 | 30.62 | 0.22 | -1.22 |

| Emissions_S | 0.00 | 99.89 | 42.68 | 16.67 | 40.75 | 68.43 | 30.29 | 0.15 | -1.18 |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.00 | 99.24 | 24.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 29.98 | 0.85 | -0.66 |

| Workforce_S | 0.41 | 99.90 | 53.04 | 27.41 | 54.50 | 77.11 | 28.17 | -0.05 | -1.22 |

| Human.Rights_S | 0.00 | 97.16 | 27.85 | 0.00 | 15.96 | 50.31 | 31.50 | 0.83 | -0.71 |

| Community_S | 0.00 | 99.91 | 43.28 | 17.50 | 34.09 | 70.89 | 29.75 | 0.41 | -1.24 |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.00 | 99.90 | 46.60 | 22.06 | 44.21 | 74.53 | 31.63 | 0.04 | -1.24 |

| Management_S | 0.27 | 99.81 | 51.73 | 27.71 | 52.13 | 76.24 | 28.19 | -0.06 | -1.19 |

| Shareholders_S | 0.14 | 99.95 | 51.64 | 27.14 | 52.63 | 75.58 | 28.08 | -0.05 | -1.19 |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.00 | 99.95 | 46.22 | 20.29 | 46.15 | 73.62 | 30.26 | 0.05 | -1.24 |

| ESG.Ow_S | 1.14 | 98.12 | 51.71 | 33.40 | 52.27 | 70.38 | 22.63 | -0.07 | -0.98 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.41 | 99.90 | 53.04 | 27.41 | 54.50 | 77.11 | 28.17 | -0.05 | -1.22 |

| ESG.Cr_S | 0.00 | 99.18 | 33.03 | 12.52 | 28.70 | 51.77 | 24.81 | 0.56 | -0.63 |

| ESG.Cy_S | 0.00 | 96.29 | 41.08 | 19.16 | 39.21 | 61.42 | 25.66 | 0.25 | -1.05 |

| ESG.S_S | 2.45 | 91.14 | 44.37 | 28.47 | 43.27 | 58.82 | 19.33 | 0.17 | -0.82 |

| ESG.In_S | 1.22 | 96.24 | 51.64 | 37.41 | 51.58 | 66.12 | 19.00 | -0.05 | -0.67 |

| ESG.Ex_S | 0.00 | 97.56 | 38.02 | 17.99 | 35.87 | 55.62 | 23.29 | 0.33 | -0.85 |

| ESG.P_S | 2.45 | 91.14 | 44.37 | 28.47 | 43.27 | 58.82 | 19.33 | 0.17 | -0.82 |

| ESG.St_S | 1.17 | 97.01 | 48.83 | 31.94 | 48.84 | 64.92 | 21.56 | 0.04 | -0.83 |

| ESG.Ta_S | 0.92 | 95.65 | 43.71 | 27.68 | 42.91 | 57.86 | 19.86 | 0.20 | -0.70 |

| ESG.Op_S | 0.00 | 98.04 | 40.99 | 18.32 | 39.19 | 62.86 | 26.19 | 0.22 | -1.08 |

| ESG.ML_S | 2.45 | 91.14 | 44.37 | 28.47 | 43.27 | 58.82 | 19.33 | 0.17 | -0.82 |

| ESG.Po_S | 0.00 | 97.91 | 38.13 | 17.85 | 36.48 | 56.70 | 24.11 | 0.28 | -0.88 |

| ESG.Ho_S | 1.22 | 95.87 | 49.87 | 35.53 | 49.26 | 63.70 | 19.02 | 0.05 | -0.64 |

| ESG.Co_S | 20.57 | 99.07 | 71.30 | 61.12 | 70.34 | 81.23 | 12.90 | 0.08 | -0.48 |

| ESG.F_S | 13.33 | 92.15 | 50.40 | 36.49 | 49.60 | 63.23 | 16.90 | 0.17 | -0.80 |

Appendix IV - Number of companies across sample countries between the ESG clusters

| 2018 | Kohonen SOM Cluster Solution | |||||

| Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | ||||

| Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country |

| BR | 54 | 58,70% | 25 | 27,17% | 13 | 14,13% |

| CL | 20 | 47,62% | 9 | 21,43% | 13 | 30,95% |

| CN | 63 | 19,15% | 153 | 46,50% | 113 | 34,35% |

| CO | 13 | 61,90% | 8 | 38,10% | - | 0,00% |

| CZ* | 1 | 33,33% | 2 | 66,67% | - | 0,00% |

| EG | 3 | 30,00% | 2 | 20,00% | 5 | 50,00% |

| GR* | 14 | 48,28% | 7 | 24,14% | 8 | 27,59% |

| HU* | 3 | 60,00% | 1 | 20,00% | 1 | 20,00% |

| IN | 72 | 63,16% | 33 | 28,95% | 9 | 7,89% |

| ID | 19 | 44,19% | 17 | 39,53% | 7 | 16,28% |

| KW | 3 | 27,27% | 4 | 36,36% | 4 | 36,36% |

| MY | 40 | 68,97% | 15 | 25,86% | 3 | 5,17% |

| MX | 28 | 56,00% | 11 | 22,00% | 11 | 22,00% |

| PE | 11 | 36,67% | 9 | 30,00% | 10 | 33,33% |

| PH | 12 | 46,15% | 9 | 34,62% | 5 | 19,23% |

| PO* | 17 | 42,50% | 16 | 40,00% | 7 | 17,50% |

| QA | 1 | 5,88% | 7 | 41,18% | 9 | 52,94% |

| RS* | 21 | 48,84% | 14 | 32,56% | 8 | 18,60% |

| SA | 7 | 20,59% | 9 | 26,47% | 18 | 52,94% |

| ZA | 69 | 61,06% | 34 | 30,09% | 10 | 8,85% |

| KR | 71 | 51,82% | 24 | 17,52% | 42 | 30,66% |

| TW | 100 | 71,43% | 23 | 16,43% | 17 | 12,14% |

| TH | 29 | 69,05% | 12 | 28,57% | 1 | 2,38% |

| TR | 36 | 66,67% | 12 | 22,22% | 6 | 11,11% |

| UA | 4 | 25,00% | 5 | 31,25% | 7 | 43,75% |

| Total | 711 | - | 461 | - | 327 | - |

| 2019 | Kohonen SOM Cluster Solution | |||||

| Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | ||||

| Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country |

| BR | 57 | 50,89% | 27 | 24,11% | 28 | 25,00% |

| CL | 22 | 52,38% | 9 | 21,43% | 11 | 26,19% |

| CN | 86 | 14,10% | 302 | 49,51% | 222 | 36,39% |

| CO | 13 | 65,00% | 7 | 35,00% | - | 0,00% |

| CZ* | 2 | 66,67% | 1 | 33,33% | - | 0,00% |

| EG | 2 | 20,00% | 2 | 20,00% | 6 | 60,00% |

| GR* | 13 | 48,15% | 8 | 29,63% | 6 | 22,22% |

| HU* | 3 | 60,00% | 1 | 20,00% | 1 | 20,00% |

| IN | 74 | 47,44% | 64 | 41,03% | 18 | 11,54% |

| ID | 18 | 39,13% | 19 | 41,30% | 9 | 19,57% |

| KW | 3 | 23,08% | 3 | 23,08% | 7 | 53,85% |

| MY | 38 | 61,29% | 20 | 32,26% | 4 | 6,45% |

| MX | 24 | 46,15% | 21 | 40,38% | 7 | 13,46% |

| PE | 10 | 33,33% | 15 | 50,00% | 5 | 16,67% |

| PH | 10 | 38,46% | 14 | 53,85% | 2 | 7,69% |

| PO* | 16 | 41,03% | 18 | 46,15% | 5 | 12,82% |

| QA | 1 | 5,26% | 8 | 42,11% | 10 | 52,63% |

| RS* | 21 | 48,84% | 19 | 44,19% | 3 | 6,98% |

| SA | 5 | 13,89% | 16 | 44,44% | 15 | 41,67% |

| ZA | 59 | 50,43% | 43 | 36,75% | 15 | 12,82% |

| KR | 75 | 48,08% | 30 | 19,23% | 51 | 32,69% |

| TW | 97 | 65,10% | 39 | 26,17% | 13 | 8,72% |

| TH | 41 | 41,00% | 40 | 40,00% | 19 | 19,00% |

| TR | 39 | 65,00% | 15 | 25,00% | 6 | 10,00% |

| UA | 3 | 17,65% | 6 | 35,29% | 8 | 47,06% |

| Total | 732 | - | 747 | -- | 471 | - |

| 2020 | Kohonen SOM Cluster Solution | |||||

| Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | ||||

| Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country |

| BR | 51 | 44.35% | 42 | 36.52% | 22 | 19.13% |

| CL | 21 | 51.22% | 14 | 34.15% | 6 | 14.63% |

| CN | 92 | 11.46% | 323 | 40.22% | 388 | 48.32% |

| CO | 11 | 57.89% | 7 | 36.84% | 1 | 5.26% |

| CZ* | 1 | 33.33% | 2 | 66.67% | - | 0.00% |

| EG | 3 | 20.00% | 6 | 40.00% | 6 | 40.00% |

| GR* | 12 | 48.00% | 8 | 32.00% | 5 | 20.00% |

| HU* | 3 | 50.00% | 1 | 16.67% | 2 | 33.33% |

| IN | 64 | 38.79% | 87 | 52.73% | 14 | 8.48% |

| ID | 16 | 31.37% | 24 | 47.06% | 11 | 21.57% |

| KW | 2 | 12.50% | 7 | 43.75% | 7 | 43.75% |

| MY | 34 | 47.89% | 33 | 46.48% | 4 | 5.63% |

| MX | 22 | 44.00% | 22 | 44.00% | 6 | 12.00% |

| PE | 10 | 34.48% | 13 | 44.83% | 6 | 20.69% |

| PH | 7 | 24.14% | 19 | 65.52% | 3 | 10.34% |

| PO* | 12 | 30.77% | 22 | 56.41% | 5 | 12.82% |

| QA | 1 | 2.27% | 5 | 11.36% | 38 | 86.36% |

| RS* | 18 | 41.86% | 18 | 41.86% | 7 | 16.28% |

| SA | 6 | 14.63% | 10 | 24.39% | 25 | 60.98% |

| ZA | 49 | 41.53% | 56 | 47.46% | 13 | 11.02% |

| KR | 74 | 51.75% | 29 | 20.28% | 40 | 27.97% |

| TW | 95 | 62.09% | 41 | 26.80% | 17 | 11.11% |

| TH | 50 | 37.04% | 57 | 42.22% | 28 | 20.74% |

| TR | 56 | 69.14% | 18 | 22.22% | 7 | 8.64% |

| UA | 4 | 16.00% | 11 | 44.00% | 10 | 40.00% |

| Total | 714 | - | 875 | - | 671 | - |

| 2021 | Kohonen SOM Cluster Solution | |||||

| Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | ||||

| Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country | Count | % Within Country |

| BR | 15 | 60.00% | 7 | 28.00% | 3 | 12.00% |

| CL | 13 | 48.15% | 9 | 33.33% | 5 | 18.52% |

| CN | 103 | 11.44% | 222 | 24.67% | 575 | 63.89% |

| CO | 5 | 50.00% | 4 | 40.00% | 1 | 10.00% |

| CZ* | 0.00% | 1 | 50.00% | 1 | 50.00% | |

| EG | 1 | 5.56% | 2 | 11.11% | 15 | 83.33% |

| GR* | 5 | 55.56% | 1 | 11.11% | 3 | 33.33% |

| HU* | 3 | 60.00% | 0.00% | 2 | 40.00% | |

| IN | 63 | 32.81% | 81 | 42.19% | 48 | 25.00% |

| ID | 12 | 32.43% | 10 | 27.03% | 15 | 40.54% |

| KW | 1 | 6.25% | 4 | 25.00% | 11 | 68.75% |

| MY | 48 | 19.67% | 83 | 34.02% | 113 | 46.31% |

| MX | 16 | 25.81% | 21 | 33.87% | 25 | 40.32% |

| PE | 5 | 27.78% | 7 | 38.89% | 6 | 33.33% |

| PH | 2 | 16.67% | 8 | 66.67% | 2 | 16.67% |

| PO* | 7 | 30.43% | 11 | 47.83% | 5 | 21.74% |

| QA | 1 | 3.23% | 2 | 6.45% | 28 | 90.32% |

| RS* | 5 | 41.67% | 5 | 41.67% | 2 | 16.67% |

| SA | 1 | 4.00% | 8 | 32.00% | 16 | 64.00% |

| ZA | 40 | 36.70% | 46 | 42.20% | 23 | 21.10% |

| KR | 6 | 40.00% | 4 | 26.67% | 5 | 33.33% |

| TW | 50 | 65.79% | 19 | 25.00% | 7 | 9.21% |

| TH | 28 | 30.43% | 41 | 44.57% | 23 | 25.00% |

| TR | 45 | 71.43% | 8 | 12.70% | 10 | 15.87% |

| UA | 4 | 11.11% | 7 | 19.44% | 25 | 69.44% |

| Total | 479 | - | 611 | - | 969 | - |

Appendix V - Number of sample companies across economic sectors between the ESG clusters.

| 2018 | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOT. | ||

| Higher ESG | Count | - | 98 | 60 | 71 | 53 | 143 | 19 | 98 | 20 | 101 | 48 | 711 |

| % within cluster | 0.00 | 13.78 | 8.44 | 9.99 | 7.45 | 20.11 | 2.67 | 13.78 | 2.81 | 14.21 | 6.75 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 0.00 | 52.41 | 39.22 | 46.10 | 66.25 | 47.99 | 26.03 | 50.78 | 27.03 | 53.44 | 50.53 | 47.43 | |

| % of total | 0.00 | 6.54 | 4.00 | 4.74 | 3.54 | 9.54 | 1.27 | 6.54 | 1.33 | 6.74 | 3.20 | 47.43 | |

| Middle ESG | Count | 3 | 46 | 48 | 35 | 17 | 110 | 27 | 57 | 36 | 55 | 27 | 461 |

| % within cluster | 0.65 | 9.98 | 10.41 | 7.59 | 3.69 | 23.86 | 5.86 | 12.36 | 7.81 | 11.93 | 5.86 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 100.0 | 24.60 | 31.37 | 22.73 | 21.25 | 36.91 | 36.99 | 29.53 | 48.65 | 29.10 | 28.42 | 30.75 | |

| % of total | 0.20 | 3.07 | 3.20 | 2.33 | 1.13 | 7.34 | 1.80 | 3.80 | 2.40 | 3.67 | 1.80 | 30.75 | |

| Lower ESG | Count | - | 43 | 45 | 48 | 10 | 45 | 27 | 38 | 18 | 33 | 20 | 327 |

| % within cluster | 0.00 | 13.15 | 13.76 | 14.68 | 3.06 | 13.76 | 8.26 | 11.62 | 5.50 | 10.09 | 6.12 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 0.00 | 22.99 | 29.41 | 31.17 | 12.50 | 15.10 | 36.99 | 19.69 | 24.32 | 17.46 | 21.05 | 21.81 | |

| % of total | 0.00 | 2.87 | 3.00 | 3.20 | 0.67 | 3.00 | 1.80 | 2.54 | 1.20 | 2.20 | 1.33 | 21.81 | |

| Total | Count | 3 | 187 | 153 | 154 | 80 | 298 | 73 | 193 | 74 | 189 | 95 | 1.499 |

| % within cluster | 0.20 | 12.47 | 10.21 | 10.27 | 5.34 | 19.88 | 4.87 | 12.88 | 4.94 | 12.61 | 6.34 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| % of total | 0.20 | 12.47 | 10.21 | 10.27 | 5.34 | 19.88 | 4.87 | 12.88 | 4.94 | 12.61 | 6.34 | 100.0 | |

| 2019 | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOT. | ||

| Higher ESG | Count | 1 | 105 | 61 | 74 | 61 | 136 | 23 | 104 | 26 | 94 | 47 | 732 |

| % within cluster | 0.14 | 14.34 | 8.33 | 10.11 | 8.33 | 18.58 | 3.14 | 14.21 | 3.55 | 12.84 | 6.42 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 20.00 | 44.49 | 28.37 | 37.56 | 66.30 | 39.88 | 18.25 | 40.47 | 25.24 | 35.21 | 42.34 | 37.54 | |

| % of total | 0.05 | 5.38 | 3.13 | 3.79 | 3.13 | 6.97 | 1.18 | 5.33 | 1.33 | 4.82 | 2.41 | 37.54 | |

| Middle ESG | Count | 4 | 94 | 82 | 64 | 19 | 129 | 61 | 93 | 48 | 105 | 48 | 747 |

| % within cluster | 0.54 | 12.58 | 10.98 | 8.57 | 2.54 | 17.27 | 8.17 | 12.45 | 6.43 | 14.06 | 6.43 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 80.00 | 39.83 | 38.14 | 32.49 | 20.65 | 37.83 | 48.41 | 36.19 | 46.60 | 39.33 | 43.24 | 38.31 | |

| % of total | 0.21 | 4.82 | 4.21 | 3.28 | 0.97 | 6.62 | 3.13 | 4.77 | 2.46 | 5.38 | 2.46 | 38.31 | |

| Lower ESG | Count | - | 37 | 72 | 59 | 12 | 76 | 42 | 60 | 29 | 68 | 16 | 471 |

| % within cluster | 0.00 | 7.86 | 15.29 | 12.53 | 2.55 | 16.14 | 8.92 | 12.74 | 6.16 | 14.44 | 3.40 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 0.00 | 15.68 | 33.49 | 29.95 | 13.04 | 22.29 | 33.33 | 23.35 | 28.16 | 25.47 | 14.41 | 24.15 | |

| % of total | 0.00 | 1.90 | 3.69 | 3.03 | 0.62 | 3.90 | 2.15 | 3.08 | 1.49 | 3.49 | 0.82 | 24.15 | |

| Total | Count | 5 | 236 | 215 | 197 | 92 | 341 | 126 | 257 | 103 | 267 | 111 | 1950 |

| % within cluster | 0.26 | 12.10 | 11.03 | 10.10 | 4.72 | 17.49 | 6.46 | 13.18 | 5.28 | 13.69 | 5.69 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| % of total | 0.26 | 12.10 | 11.03 | 10.10 | 4.72 | 17.49 | 6.46 | 13.18 | 5.28 | 13.69 | 5.69 | 100.0 | |

| 2020 | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOT. | ||

| Higher ESG | Count | - | 102 | 71 | 69 | 54 | 130 | 27 | 90 | 34 | 91 | 46 | 714 |

| % within cluster | 0.00 | 14.29 | 9.94 | 9.66 | 7.56 | 18.21 | 3.78 | 12.61 | 4.76 | 12.75 | 6.44 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 0.00 | 34.81 | 27.95 | 30.26 | 52.43 | 34.67 | 18.75 | 29.13 | 29.06 | 29.64 | 36.80 | 31.59 | |

| % of total | 0.00 | 4.51 | 3.14 | 3.05 | 2.39 | 5.75 | 1.19 | 3.98 | 1.50 | 4.03 | 2.04 | 31.59 | |

| Middle ESG | Count | 5 | 107 | 95 | 79 | 34 | 155 | 66 | 119 | 44 | 122 | 49 | 875 |

| % within cluster | 0.57 | 12.23 | 10.86 | 9.03 | 3.89 | 17.71 | 7.54 | 13.60 | 5.03 | 13.94 | 5.60 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 100.0 | 36.52 | 37.40 | 34.65 | 33.01 | 41.33 | 45.83 | 38.51 | 37.61 | 39.74 | 39.20 | 38.72 | |

| % of total | 0.22 | 4.73 | 4.20 | 3.50 | 1.50 | 6.86 | 2.92 | 5.27 | 1.95 | 5.40 | 2.17 | 38.72 | |

| Lower ESG | Count | - | 84 | 88 | 80 | 15 | 90 | 51 | 100 | 39 | 94 | 30 | 671 |

| % within cluster | 0.00 | 12.52 | 13.11 | 11.92 | 2.24 | 13.41 | 7.60 | 14.90 | 5.81 | 14.01 | 4.47 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 0.00 | 28.67 | 34.65 | 35.09 | 14.56 | 24.00 | 35.42 | 32.36 | 33.33 | 30.62 | 24.00 | 29.69 | |

| % of total | 0.00 | 3.72 | 3.89 | 3.54 | 0.66 | 3.98 | 2.26 | 4.42 | 1.73 | 4.16 | 1.33 | 29.69 | |

| Total | Count | 5 | 293 | 254 | 228 | 103 | 375 | 144 | 309 | 117 | 307 | 125 | 2260 |

| % within cluster | 0.22 | 12.96 | 11.24 | 10.09 | 4.56 | 16.59 | 6.37 | 13.67 | 5.18 | 13.58 | 5.53 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| % of total | 0.22 | 12.96 | 11.24 | 10.09 | 4.56 | 16.59 | 6.37 | 13.67 | 5.18 | 13.58 | 5.53 | 100.0 | |

| 2021 | Economic Sector | ||||||||||||

| ACD | BMT | CCS | CNC | ENG | FIN | HLC | IND | RES | TEC | UTL | TOT. | ||

| Higher ESG | Count | 1 | 66 | 49 | 48 | 34 | 97 | 20 | 58 | 22 | 69 | 15 | 479 |

| % within cluster | 0.21 | 13.78 | 10.23 | 10.02 | 7.10 | 20.25 | 4.18 | 12.11 | 4.59 | 14.41 | 3.13 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 33.33 | 22.22 | 21.97 | 24.87 | 40.48 | 29.04 | 12.82 | 18.47 | 19.64 | 25.84 | 19.74 | 23.26 | |

| % of total | 0.05 | 3.21 | 2.38 | 2.33 | 1.65 | 4.71 | 0.97 | 2.82 | 1.07 | 3.35 | 0.73 | 23.26 | |

| Middle ESG | Count | 1 | 78 | 67 | 50 | 27 | 111 | 63 | 79 | 31 | 78 | 26 | 611 |

| % within cluster | 0.16 | 12.77 | 10.97 | 8.18 | 4.42 | 18.17 | 10.31 | 12.93 | 5.07 | 12.77 | 4.26 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 33.33 | 26.26 | 30.04 | 25.91 | 32.14 | 33.23 | 40.38 | 25.16 | 27.68 | 29.21 | 34.21 | 29.67 | |

| % of total | 0.05 | 3.79 | 3.25 | 2.43 | 1.31 | 5.39 | 3.06 | 3.84 | 1.51 | 3.79 | 1.26 | 29.67 | |

| Lower ESG | Count | 1 | 153 | 107 | 95 | 23 | 126 | 73 | 177 | 59 | 120 | 35 | 969 |

| % within cluster | 0.10 | 15.79 | 11.04 | 9.80 | 2.37 | 13.00 | 7.53 | 18.27 | 6.09 | 12.38 | 3.61 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 33.33 | 51.52 | 47.98 | 49.22 | 27.38 | 37.72 | 46.79 | 56.37 | 52.68 | 44.94 | 46.05 | 47.06 | |

| % of total | 0.05 | 7.43 | 5.20 | 4.61 | 1.12 | 6.12 | 3.55 | 8.60 | 2.87 | 5.83 | 1.70 | 47.06 | |

| Total | Count | 3 | 297 | 223 | 193 | 84 | 334 | 156 | 314 | 112 | 267 | 76 | 2059 |

| % within cluster | 0.15 | 14.42 | 10.83 | 9.37 | 4.08 | 16.22 | 7.58 | 15.25 | 5.44 | 12.97 | 3.69 | 100.0 | |

| % within ec.sector | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| % of total | 0.15 | 14.42 | 10.83 | 9.37 | 4.08 | 16.22 | 7.58 | 15.25 | 5.44 | 12.97 | 3.69 | 100.0 | |

Appendix VI – Clusters’ Medians.

| Year | Cluster | ESG_S | ENV_S | SOC_S | GOV_S | Combined_S |

| 2018 | Higher ESG | 61.87 | 60.70 | 67.64 | 61.14 | 60.47 |

| Middle ESG | 36.51 | 21.97 | 35.70 | 50.00 | 36.39 | |

| Lower ESG | 16.32 | 3.72 | 11.87 | 24.67 | 16.32 | |

| 2019 | Higher ESG | 63.98 | 64.36 | 69.34 | 61.89 | 62.44 |

| Middle ESG | 38.55 | 28.36 | 37.06 | 53.13 | 38.23 | |

| Lower ESG | 17.53 | 4.37 | 12.41 | 27.61 | 17.53 | |

| 2020 | Higher ESG | 67.23 | 68.94 | 72.61 | 59.90 | 65.44 |

| Middle ESG | 43.68 | 33.94 | 44.53 | 53.70 | 42.97 | |

| Lower ESG | 20.68 | 6.94 | 13.54 | 37.63 | 20.68 | |

| 2021 | Higher ESG | 69.98 | 68.97 | 74.03 | 64.36 | 67.56 |

| Middle ESG | 50.56 | 43.71 | 53.28 | 51.41 | 50.19 | |

| Lower ESG | 27.31 | 14.53 | 20.17 | 43.46 | 27.18 |

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||||||||||

| Variable | Higher | Middle | Lower | Higher | Middle | Lower | Higher | Middle | Lower | Higher | Middle | Lower | ||

| Resource.Use | 76.96 | 52.13 | 8.10 | 75.88 | 48.41 | 5.80 | 80.56 | 49.81 | 4.51 | 80.68 | 56.08 | 12.14 | ||

| Emissions | 79.29 | 56.32 | 9.35 | 76.98 | 51.48 | 6.15 | 81.33 | 48.42 | 7.30 | 80.67 | 53.99 | 17.69 | ||

| Environmental.Innovation | 50.00 | 17.87 | 0.00 | 46.58 | 25.70 | 0.00 | 49.18 | 24.29 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 16.55 | 0.00 | ||

| Workforce | 85.78 | 68.92 | 29.42 | 84.29 | 67.61 | 26.04 | 87.69 | 63.75 | 22.62 | 87.04 | 67.78 | 27.34 | ||

| Human.Rights | 73.19 | 25.19 | 0.00 | 72.17 | 18.45 | 0.00 | 71.86 | 23.24 | 0.00 | 78.91 | 28.15 | 0.00 | ||

| Community | 81.93 | 41.09 | 15.98 | 79.51 | 31.01 | 14.77 | 80.66 | 43.31 | 15.97 | 83.62 | 43.83 | 19.70 | ||

| Product.Responsibility | 76.62 | 65.95 | 15.64 | 75.06 | 52.67 | 16.28 | 77.97 | 60.97 | 15.05 | 78.13 | 58.66 | 25.71 | ||

| Management | 64.15 | 50.99 | 37.50 | 62.60 | 49.28 | 38.68 | 64.24 | 51.16 | 39.24 | 64.61 | 56.09 | 44.88 | ||

| Shareholders | 53.92 | 50.00 | 45.36 | 53.18 | 49.78 | 49.78 | 55.92 | 50.76 | 50.00 | 56.57 | 49.50 | 51.62 | ||

| CSR.Strategy | 74.29 | 48.82 | 8.33 | 72.87 | 53.26 | 6.60 | 79.82 | 45.21 | 7.30 | 79.27 | 59.93 | 23.44 | ||

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||||||||||

| Variable | Higher | Middle | Lower | Higher | Middle | Lower | Higher | Middle | Lower | Higher | Middle | Lower | ||

| ESG.Ow_S | 69.72 | 33.16 | 44.59 | 66.08 | 41.09 | 44.21 | 59.81 | 56.73 | 36.73 | 67.70 | 30.74 | 43.46 | ||

| ESG.Em_S | 82.30 | 65.84 | 25.78 | 87.11 | 70.79 | 28.54 | 82.05 | 52.24 | 21.91 | 78.73 | 72.67 | 27.38 | ||

| ESG.Cr_S | 52.56 | 36.60 | 8.76 | 64.06 | 25.84 | 13.28 | 49.27 | 33.63 | 11.10 | 51.15 | 34.19 | 14.40 | ||

| ESG.Cy_S | 67.53 | 46.87 | 12.46 | 74.01 | 49.28 | 15.40 | 66.64 | 35.66 | 12.81 | 64.25 | 55.01 | 19.16 | ||

| ESG.S_S | 66.66 | 46.28 | 23.99 | 69.40 | 48.69 | 26.46 | 62.53 | 43.76 | 23.08 | 63.66 | 49.10 | 28.25 | ||

| ESG.In_S | 71.48 | 47.20 | 19.80 | 68.10 | 47.31 | 24.53 | 75.83 | 54.09 | 34.10 | 71.21 | 49.13 | 28.54 | ||

| ESG.Ex_S | 62.57 | 30.77 | 6.17 | 60.48 | 26.79 | 8.19 | 65.57 | 47.43 | 14.38 | 61.49 | 27.42 | 16.68 | ||

| ESG.P_S | 65.70 | 38.95 | 14.09 | 61.59 | 35.90 | 16.37 | 70.51 | 50.62 | 25.16 | 64.94 | 40.67 | 21.75 | ||

| ESG.St_S | 71.70 | 54.14 | 27.23 | 73.27 | 54.42 | 31.15 | 66.72 | 41.83 | 19.19 | 67.79 | 60.78 | 30.86 | ||

| ESG.Ta_S | 72.07 | 49.64 | 25.23 | 73.10 | 49.73 | 26.95 | 61.62 | 37.52 | 16.92 | 68.50 | 48.00 | 26.14 | ||

| ESG.Op_S | 77.73 | 51.90 | 14.03 | 79.69 | 54.22 | 13.74 | 69.12 | 28.84 | 6.31 | 76.82 | 47.16 | 16.65 | ||

| ESG.ML_S | 72.57 | 51.67 | 24.85 | 75.67 | 52.90 | 25.45 | 63.74 | 36.42 | 15.35 | 71.28 | 50.96 | 26.61 | ||

| ESG.Po_S | 62.99 | 30.32 | 4.25 | 56.34 | 33.10 | 10.31 | 58.17 | 59.07 | 18.70 | 59.11 | 56.37 | 19.91 | ||

| ESG.Ho_S | 68.30 | 45.54 | 14.67 | 63.28 | 50.84 | 28.50 | 64.55 | 58.47 | 37.79 | 64.34 | 67.76 | 37.93 | ||

| ESG.Co_S | 85.78 | 64.72 | 53.51 | 81.43 | 62.64 | 58.00 | 82.34 | 47.74 | 61.78 | 83.50 | 58.72 | 63.17 | ||

| ESG.F_S | 68.76 | 44.63 | 20.56 | 63.29 | 47.02 | 29.39 | 65.51 | 56.05 | 36.93 | 65.41 | 59.56 | 37.62 | ||

References

- Hübel, B.; Scholz, H. Integrating sustainability risks in asset management: the role of ESG exposures and ESG ratings. Journal of Asset Management, 2020, 21, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassen, A.; Meyer, K.; Schlange, J. The influence of corporate responsibility on the cost of capital (Working paper series), University of Hamburg. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Benjamin, J. D. Corporate social performance, and firm risk: A metanalytic review. Business and Society, 2001, 40, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyawati, L. A systematic literature review of socially responsible investment and environmental social governance metrics. Business Strategy and Environment, 2020, 29, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldowaish, A.; Kokuryo, J.; Almazyad, O.; Goi, H.C. Environmental, Social, and Governance Integration into the Business Model: Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability, 2022, 14, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamandi, I.E.; Constantin, L.G.; Munteanu, S.M.; Cernat-Gruici, B. Mapping the ESG Behavior of European Companies. A Holistic Kohonen Approach. Sustainability, 2019, 11, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Rahman, Z. Corporate sustainability performance and firm performance: Literature review and future research agenda. Management Decision, 2013, 51, 361–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Baumgartner, R.J. Corporate sustainability strategy – bridging the gap between formulation and implementation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2016, 113, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortas, E.; Álvarez, I.; Jaussaud, J.; Garayar, A. The impact of institutional and social context on corporate environmental, social and governance performance of companies committed to voluntary corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015, 108, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, F.A.F.S.; Oliveira, E.M.; Orsato, R.J.; Klotzle, M.C.; Oliveira, F.L.C.; Caiado, R.G.G. Can sustainable investments outperform traditional benchmarks? Evidence from global stock markets. Business Strategy and the Environment, 2020, 29, 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review. Journal of Business Ethics, 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Hills, G.; Pfitzer, M.; Patscheke, S.; Hawkins, E. Measuring Shared Value: How to Unlock Value by Linking Business and Social Results. Foundation Strategy Group (FSG), 2012. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=46910 (accessed on 01 July 2022).

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birindelli, G.; Dell’Atti, S.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Savioli, M. Composition and activity of the board of directors: Impact on ESG performance in the banking system. Sustainability, 2018, 10, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disli, M.; Yilmaz, M.K.; Mohamed, F.F.M. Board characteristics and sustainability performance: empirical evidence from emerging markets. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 2022, 13, 4–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Consequences of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting (May 1, 2017). Harvard Business School Research Working Paper No. 11-100. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1799589.

- Jitmaneeroj, B. Reform priorities for corporate sustainability: Environmental, social, governance, or economic performance? Management Decision, 2016, 54, 1497–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 18. Engelhardt, N; Ekkenga, J.; Posch, P. ESG Ratings and Stock Performance during the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability, 2021; 13, 7133.

- Kluza, K.; Ziolo, M.; Spoz, A. Innovation and environmental, social, and governance factors influencing sustainable business models - Meta-analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021, 303, 127015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Nagy, Z.; Lee, L.E. Deconstructing ESG Ratings Performance: Risk and Return for E, S, and G by Time Horizon, Sector, and Weighting. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 2021, 47, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, M.M.; Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Gonçalves, L.M.V. The Value Relevance of Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: The Brazilian Case. Sustainability, 2018, 10, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, M.F; Rahman, R.A; Homayoun, S. Corporate Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability Performance Transformation through ESG Disclosure. Sustainability, 2020, 12, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, G.; Cortez, M. and Ferruz, L. Socially responsible investing worldwide: Do markets value corporate social responsibility? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 2020, 27, 2751–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Wu, D.A.; Yaron, A. Socially Responsible Investing in Good and Bad Times. The Review of Financial Studies, 2021, 00, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J.; Li, Z. Does external uncertainty matter in corporate sustainability performance? Journal of Corporate Finance, 2020, 65, 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Maps, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaski, S; Kohonen, T. Winners-Takes-All network. In: Triennial Report (1994-1996). Neural Networks Research Centre & Laboratory of Computer and Information Science. Helsinky University of Technology, Finland, 1997.

- Wehrens, R.; Kruisselbrink, J. Flexible Self-Organizing Maps in kohonen 3.0. Journal of Statistical Software, 2018, 87, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrens, R.; Buydens, L.M.C. Self- and Super-Organizing Maps in R: The kohonen Package. Journal of Statistical Software, 2007, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelaert, J.; Ollion, E.; Sodoge, J. aweSOM: Interactive Self-Organizing Maps. R package version 1.2. 2021. https://CRAN.R-projectorg/package=aweSOM.

- Kuhn, M. caret: Classification and Regression Training. R package version 6.0-92. 2022. https://CRAN.R-projectorg/package=caret.

- Maechler, M.; Rousseeuw, P.; Struyf, A.; Hubert, M.; Hornik, K. cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions. R package version 2.1.3. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.S.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W.; Orsato, R.J. Sensitive industries produce better ESG performance: Evidence from emerging markets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2017; 150, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Berglund, E.; Sitte, J. The parameterless self-organizing map algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 2006, 17, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, H.; Herrmann, M.; Villmann, T. Neural maps and topographic vector quantization. Neural Networks, 1999, 12, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. Journal of Business Ethics, 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franco, C. ESG Controversies and Their Impact on Performance. The Journal of Investing ESG, 2020, 29, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harvard Business Review 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaescu, E.; Alpopi, C.; Zaharia, C. Measuring Corporate Sustainability Performance. Sustainability, 2015, 7, 851–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 2008, 29, 1325–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaliano, D.F. Corporate social responsibility, and labor turnover. Corporate Governance, 2010, 10, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | 2019 in comparison to 2018 | 2020 in comparison to 2019 | 2021 in comparison to 2020 | 2021 in comparison to 2018 |

| BR | 21,74% | 2,68% | -78,26% | -72,83% |

| CL | 0,00% | -2,38% | -34,15% | -35,71% |

| CN | 85,41% | 31,64% | 12,08% | 173,56% |

| CO | -4,76% | -5,00% | -47,37% | -52,38% |

| CZ* | 0,00% | 0,00% | -33,33% | -33,33% |

| EG | 0,00% | 50,00% | 20,00% | 80,00% |

| GR* | -6,90% | -7,41% | -64,00% | -68,97% |

| HU* | 0,00% | 20,00% | -16,67% | 0,00% |

| IN | 36,84% | 5,77% | 16,36% | 68,42% |

| ID | 6,98% | 10,87% | -27,45% | -13,95% |

| KW | 18,18% | 23,08% | 0,00% | 45,45% |

| MY | 6,90% | 14,52% | 243,66% | 320,69% |

| MX | 4,00% | -3,85% | 24,00% | 24,00% |

| PE | 0,00% | -3,33% | -37,93% | -40,00% |

| PH | 0,00% | 11,54% | -58,62% | -53,85% |

| PO* | -2,50% | 0,00% | -41,03% | -42,50% |

| QA | 11,76% | 131,58% | -29,55% | 82,35% |

| RS* | 0,00% | 0,00% | -72,09% | -72,09% |

| SA | 5,88% | 13,89% | -39,02% | -26,47% |

| ZA | 3,54% | 0,85% | -7,63% | -3,54% |

| KR | 13,87% | -8,33% | -89,51% | -89,05% |

| TW | 6,43% | 2,68% | -50,33% | -45,71% |

| TH | 138,10% | 35,00% | -31,85% | 119,05% |

| TR | 11,11% | 35,00% | -22,22% | 16,67% |

| UA | 6,25% | 47,06% | 44,00% | 125,00% |

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total |

| 2018 | 1,499 | - | - | - | 1,499 |

| 2019 | 1,486 (99.13%) |

464 | - | - | 1,950 |

| 2020 | 1,450 (96.73%) |

454 (97.84%) |

356 | - | 2,260 |

| 2021 | 923 (61.57%) |

361 (77.80%) |

255 (71.63%) |

520 | 2,059 |

| ESG View | Main Components | ESG Categories (No. of Indicators) |

| ESG Stakeholder Score (ESG.S_S) |

ESG Owner Score (ESG.Ow_S) |

Management (34) Shareholders (12) |

| ESG Employee Score (ESG.Em_S) |

Workforce (29) | |

| ESG Consumer Score (ESG.Cr_S) |

Environmental Innovation (19) Product Responsibility (12) |

|

| ESG Community Score (ESG.Cy_S) |

Resource Use (20) Emissions (22) Human Rights (8) Community (14) CSR Strategy (8) |

|

| ESG Perspective Score (ESG.P_S) | ESG Internal Score (ESG.In_S) |

Workforce (29) Management (34) Shareholders (12) CSR Strategy (8) |

| ESG External Score (ESG.Ex_S) |

Resource Use (20) Emissions (22) Environmental Innovation (19) Human Rights (8) Community (14) Product Responsibility (12) |

|

| ESG Management Level Score (ESG.ML_S) |

ESG Strategic Score (ESG.St_S) |

Community (14) Management (34) CSR Strategy (8) |

| ESG Tactical Score (ESG.Ta_S) |

Environmental Innovation (19) Workforce (29) Shareholders (12) |

|

| ESG Operational Score (ESG.Op_S) |

Resource Use (20) Emissions (22) Human Rights (8) Product Responsibility (12) |

|

| ESG Focus Score (ESG.F_S) |

ESG Process Oriented Score—ESG Technology Innovation (ESG.Po_S) |

Resource Use (20) Emissions (22) Environmental Innovation (19) Product Responsibility (12) |

| ESG Human Oriented Score—ESG Relationship (ESG.Ho_S) | Workforce (29) Human Rights (8) Management (34) Shareholders (12) |

|

| ESG Communication Oriented Score—ESG Image (ESG.Co_S) |

Community (14) CSR Strategy (8) Controversies (23) |

| ESG Risks Exposure (ESG_RE) | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|

29 (1.93%) |

40 (2.05%) |

41 (1.81%) |

24 (1.17%) |

|

46 (3.07%) |

49 (2.51%) |

64 (2.83%) |

34 (1.65%) |

|

1,424 (95.00%) |

1,861 (95.43%) |

2,155 (95.35%) |

2,001 (97.18%) |

| Total | 1,499 | 1,950 | 2,260 | 2,059 |

| Clustering result for: | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Total ESG performance | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| Thematic ESG performance | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| Stakeholder View | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.26 |

| Perspective View | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

| Management Level View | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Focus View | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.32 |

| Year | Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | Total |

| 2018 | 711 (47.43%) |

461 (30.75%) |

327 (21.82%) |

1,499 |

| 2019 | 732 (37.54%) |

747 (38.31%) |

471 (24.15%) |

1,950 |

| 2020 | 714 (31.59%) |

875 (38.72%) |

671 (29.69%) |

2,260 |

| 2021 | 479 (23.26%) |

611 (29.67%) |

969 (47.07%) |

2,059 |

| Year | ESG Pillar | Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | Measure | Impact Factor |

| 2018 | ENV_S | 0.825 | -0.533 | -1.043 | 1.868 | 0.898 |

| SOC_S | 0.829 | -0.391 | -1.251 | 2.080 | 1.000 | |

| GOV_S | 0.452 | 0.028 | -1.023 | 1.475 | 0.709 | |

| 2019 | ENV_S | 1.064 | -0.355 | -1.092 | 2.156 | 1.000 |

| SOC_S | 0.933 | -0.238 | -1.073 | 2.006 | 0.930 | |

| GOV_S | 0.466 | 0.118 | -0.911 | 1.377 | 0.639 | |

| 2020 | ENV_S | 1.149 | -0.147 | -1.032 | 2.181 | 1.000 |

| SOC_S | 1.032 | 0.015 | -1.118 | 2.150 | 0.986 | |

| GOV_S | 0.402 | 0.086 | -0.540 | 0.942 | 0.432 | |

| 2021 | ENV_S | 1.246 | 0.258 | -0.779 | 2.025 | 0.986 |

| SOC_S | 1.194 | 0.429 | -0.860 | 2.054 | 1.000 | |

| GOV_S | 0.654 | 0.021 | -0.336 | 0.990 | 0.482 |

| ESG Pillars | ||||

| Measure | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Quantization error | 0.153 | 0.158 | 0.162 | 0.169 |

| Topographic error | 0.103 | 0.094 | 0.092 | 0.107 |

| (% explained variance) | 94.91 | 94.72 | 94.61 | 94.35 |

| Cluster | x=100 | 100<x≤80 | 80< x≤60 | 60< x≤40 | 40< x≤20 | 20< x≤0 | Total | |

| 2018 | Higher ESG | 602 (40.16%) |

25 (1.67%) |

23 (1.53%) |

21 (1.40%) |

22 (1.47%) |

18 (1.20%) |

711 |

| Middle ESG | 433 (28.89%) |

3 (0.20%) |

7 (0.47%) |

8 (0.53%) |

7 (0.47%) |

3 (0.20%) |

461 | |

| Lower ESG | 315 (21.01%) |

2 (0.13%) |

3 (0.20%) |

5 (0.33%) |

1 (0.07%) |

1 (0.07%) |

327 | |

| 20 19 |

Higher ESG | 595 (30.51%) |

37 (1.90%) |

29 (1.49%) |

23 (1.18%) |

25 (1.28%) |

23 (1.18%) |

732 |

| Middle ESG | 706 (36.21%) |

5 (0.26%) |

7 (0.36%) |

9 (0.46%) |

14 (0.72%) |

6 (0.31%) |

747 | |

| Lower ESG | 461 (23.64%) |

1 (0.05%) |

2 (0.10%) |

4 (0.21%) |

2 (0.10%) |

1 (0.05%) |

471 | |

| 2020 | Higher ESG | 550 (24.34%) |

24 (1.06%) |

64 (2.83%) |

21 (0.93%) |

33 (%) |

22 (0.97%) |

714 |

| Middle ESG | 779 (34.47%) |

20 (0.88%) |

38 (1.68%) |

12 (0.53%) |

20 (0.88%) |

6 (0.27%) |

875 | |

| Lower ESG | 654 (28.94%) |

2 (0.09%) |

11 (0.49%) |

2 (0.09%) |

2 (0.09%) |

- (0.00%) |

671 | |

| 2021 | Higher ESG | 412 (20.01%) |

8 (0.39%) |

18 (0.87%) |

18 (0.87%) |

10 (0.49%) |

13 (0.63%) |

479 |

| Middle ESG | 570 (27.68%) |

4 (0.19%) |

19 (0.92%) |

2 (0.10%) |

12 (0.58%) |

4 (0.19%) |

611 | |

| Lower ESG | 953 (46.28%) |

3 (0.15%) |

6 (0.29%) |

4 (0.19%) |

3 (0.15%) |

- (0.00%) |

969 |

| Year | Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | Total |

| 2018 | 434 (28.95%) |

414 (27.62%) |

651 (43.43%) |

1,499 |

| 2019 | 574 (29.44%) |

589 (30.20%) |

787 (40.36%) |

1,950 |

| 2020 | 569 (25.18%) |

878 (38.85%) |

813 (35.97%) |

2,260 |

| 2021 | 439 (21.32%) |

618 (30.02%) |

1,002 (48.66%) |

2,059 |

| Year | ESG Components | Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | Measure | Impact Factor |

| 2018 | Resource.Use_S | 0.967 | 0.337 | -0.859 | 1.827 | 0.991 |

| Emissions | 0.971 | 0.350 | -0.870 | 1.840 | 0.998 | |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.635 | 0.101 | -0.488 | 1.123 | 0.609 | |

| Workforce_S | 0.858 | 0.378 | -0.812 | 1.670 | 0.906 | |

| Human.Rights_S | 1.123 | -0.042 | -0.722 | 1.844 | 1.000 | |

| Community_S | 0.962 | -0.003 | -0.640 | 1.602 | 0.869 | |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.652 | 0.480 | -0.741 | 1.393 | 0.755 | |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.844 | 0.208 | -0.695 | 1.539 | 0.835 | |

| 2019 | Resource.Use_S | 1.014 | 0.265 | -0.938 | 1.952 | 0.986 |

| Emissions | 0.985 | 0.263 | -0.916 | 1.901 | 0.961 | |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.565 | 0.180 | -0.547 | 1.112 | 0.562 | |

| Workforce_S | 0.856 | 0.383 | -0.911 | 1.767 | 0.893 | |

| Human.Rights_S | 1.240 | -0.221 | -0.739 | 1.979 | 1.000 | |

| Community_S | 1.003 | -0.095 | -0.661 | 1.664 | 0.841 | |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.686 | 0.217 | -0.663 | 1.349 | 0.682 | |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.754 | 0.325 | -0.793 | 1.547 | 0.782 | |

| 2020 | Resource.Use_S | 1.085 | 0.214 | -0.991 | 2.076 | 1.000 |

| Emissions | 1.055 | 0.160 | -0.911 | 1.965 | 0.965 | |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.597 | 0.106 | -0.532 | 1.129 | 0.544 | |

| Workforce_S | 0.977 | 0.275 | -0.981 | 1.958 | 0.943 | |

| Human.Rights_S | 1.216 | -0.032 | -0.817 | 2.033 | 0.979 | |

| Community_S | 1.028 | 0.106 | -0.834 | 1.862 | 0.897 | |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.740 | 0.317 | -0.860 | 1.600 | 0.771 | |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.920 | 0.121 | -0.775 | 1.696 | 0.817 | |

| 2021 | Resource.Use_S | 1.184 | 0.489 | -0.821 | 2.004 | 0.954 |

| Emissions | 1.163 | 0.378 | -0.743 | 1.905 | 0.907 | |

| Environmental.Innovation_S | 0.651 | 0.128 | -0.364 | 1.015 | 0.483 | |

| Workforce_S | 1.077 | 0.504 | -0.783 | 1.859 | 0.885 | |

| Human.Rights_S | 1.411 | 0.116 | -0.690 | 2.100 | 1.000 | |

| Community_S | 1.212 | 0.162 | -0.631 | 1.843 | 0.878 | |

| Product.Responsibility_S | 0.746 | 0.364 | -0.551 | 1.297 | 0.618 | |

| CSR.Strategy_S | 0.898 | 0.454 | -0.673 | 1.571 | 0.748 |

| Thematic ESG | ||||

| Measure | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Quantization error | 1.476 | 1.429 | 1.446 | 1.469 |

| Topographic error | 0.159 | 0.150 | 0.189 | 0.147 |

| (% explained variance) | 81.54 | 82.13 | 81.92 | 81.63 |

| Year | View | Cluster | |||

| Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | Total | ||

| 2018 | Stakeholder View | 484 (32.29%) |

496 (33.09%) |

519 (34.62%) |

1,499 |

| Perspective View | 533 (35.56%) |

714 (47.63%) |

252 (16.81%) |

1,499 | |

| Management Level View | 297 (19.81%) |

606 (40.43%) |

596 (39.76%) |

1,499 | |

| Focus View | 508 (33.89%) |

816 (54.44%) |

175 (11.67%) |

1,499 | |

| 2019 | Stakeholder View | 496 (25.44%) |

563 (28.87%) |

891 (45.69%) |

1,950 |

| Perspective View | 843 (43.23%) |

734 (37.64%) |

373 (19.13%) |

1,950 | |

| Management Level View | 280 (14.36%) |

816 (41.85%) |

854 (43.79%) |

1,950 | |

| Focus View | 950 (48.72%) |

415 (21.28%) |

585 (0.30%) |

1,950 | |

| 2020 | Stakeholder View | 1,026 (45.40%) |

438 (19.38%) |

796 (35.22%) |

2,260 |

| Perspective View | 508 (22.48%) |

829 (36.68%) |

923 (40.84%) |

2,260 | |

| Management Level View | 940 (41.59%) |

978 (43.27%) |

342 (15.13%) |

2,260 | |

| Focus View | 1,011 (44.73%) |

105 (4.65%) |

1,144 (50.62%) |

2,260 | |

| 2021 | Stakeholder View | 774 (37.59%) |

275 (13.36%) |

1,010 (49.05%) |

2,059 |

| Perspective View | 703 (34.14%) |

848 (41.19%) |

508 (24.67%) |

2,059 | |

| Management Level View | 405 (19.67%) |

776 (37.69%) |

878 (42.64%) |

2,059 | |

| Focus View | 822 (39.92%) |

107 (5.20%) |

1,130 (54.88%) |

2,059 | |

| Year | View | Components | Higher ESG | Middle ESG | Lower ESG | Measure | Impact Factor |

| 2018 | ESG.S_S | ESG.Ow_S | 0.869 | -0.612 | -0.226 | 1.481 | 0.764 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.784 | 0.245 | -0.965 | 1.749 | 0.902 | ||

| ESG.Cr_S | 0.663 | 0.268 | -0.874 | 1.537 | 0.793 | ||

| ESG.Cy_S | 0.929 | 0.150 | -1.010 | 1.939 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.P_S | ESG.In_S | 0.987 | -0.187 | -1.559 | 2.546 | 1.000 | |

| ESG.Ex_S | 0.938 | -0.262 | -1.242 | 2.180 | 0.856 | ||

| ESG.ML_S | ESG.St_S | 0.956 | 0.300 | -0.781 | 1.737 | 0.788 | |

| ESG.Ta_S | 1.257 | 0.231 | -0.861 | 2.118 | 0.961 | ||

| ESG.Op_S | 1.253 | 0.320 | -0.950 | 2.203 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.F_S | ESG.Po_S | 0.898 | -0.299 | -1.211 | 2.109 | 0.811 | |

| ESG.Ho_S | 0.864 | -0.165 | -1.737 | 2.601 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.Co_S | 1.022 | -0.409 | -1.058 | 2.080 | 0.800 | ||

| 2019 | ESG.S_S | ESG.Ow_S | 0.560 | -0.167 | -0.206 | 0.766 | 0.389 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.989 | 0.533 | -0.888 | 1.877 | 0.953 | ||

| ESG.Cr_S | 1.187 | -0.189 | -0.541 | 1.728 | 0.877 | ||

| ESG.Cy_S | 1.139 | 0.312 | -0.831 | 1.970 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.P_S | ESG.In_S | 0.791 | -0.212 | -1.371 | 2.162 | 1.000 | |

| ESG.Ex_S | 0.926 | -0.473 | -1.163 | 2.089 | 0.966 | ||

| ESG.ML_S | ESG.St_S | 1.152 | 0.279 | -0.645 | 1.797 | 0.778 | |

| ESG.Ta_S | 1.397 | 0.311 | -0.755 | 2.152 | 0.932 | ||

| ESG.Op_S | 1.404 | 0.465 | -0.905 | 2.309 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.F_S | ESG.Po_S | 0.670 | -0.150 | -0.982 | 1.764 | 1.000 | |

| ESG.Ho_S | 0.639 | 0.079 | -1.094 | 1.733 | 0.982 | ||

| ESG.Co_S | 0.768 | -0.680 | -0.765 | 1.533 | 0.869 | ||

| 2020 | ESG.S_S | ESG.Ow_S | 0.242 | 0.246 | -0.447 | 0.693 | 0.368 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.843 | -0.101 | -1.031 | 1.874 | 0.996 | ||

| ESG.Cr_S | 0.589 | 0.092 | -0.810 | 1.399 | 0.744 | ||

| ESG.Cy_S | 0.874 | -0.217 | -1.007 | 1.881 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.P_S | ESG.In_S | 1.260 | 0.166 | -0.843 | 2.103 | 1.000 | |

| ESG.Ex_S | 1.087 | 0.398 | -0.956 | 2.043 | 0.971 | ||

| ESG.ML_S | ESG.St_S | 0.757 | -0.284 | -1.268 | 2.025 | 0.927 | |

| ESG.Ta_S | 0.839 | -0.336 | -1.346 | 2.185 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.Op_S | 0.929 | -0.459 | -1.240 | 2.169 | 0.993 | ||

| ESG.F_S | ESG.Po_S | 0.725 | 0.753 | -0.709 | 1.462 | 0.669 | |

| ESG.Ho_S | 0.667 | 0.470 | -0.632 | 1.299 | 0.595 | ||

| ESG.Co_S | 0.861 | -1.742 | -0.601 | 2.603 | 1.000 | ||

| 2021 | ESG.S_S | ESG.Ow_S | 0.658 | -0.935 | -0.250 | 1.593 | 0.977 |

| ESG.Em_S | 0.793 | 0.718 | -0.803 | 1.596 | 0.979 | ||

| ESG.Cr_S | 0.702 | 0.247 | -0.605 | 1.307 | 0.802 | ||

| ESG.Cy_S | 0.839 | 0.542 | -0.791 | 1.630 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.P_S | ESG.In_S | 1.019 | -0.087 | -1.266 | 2.285 | 1.000 | |

| ESG.Ex_S | 1.015 | -0.339 | -0.839 | 1.854 | 0.811 | ||

| ESG.ML_S | ESG.St_S | 0.651 | 0.554 | -0.790 | 1.441 | 0.681 | |

| ESG.Ta_S | 1.305 | 0.221 | -0.798 | 2.103 | 0.994 | ||

| ESG.Op_S | 1.319 | 0.213 | -0.796 | 2.115 | 1.000 | ||

| ESG.F_S | ESG.Po_S | 0.850 | 0.750 | -0.689 | 1.539 | 0.731 | |

| ESG.Ho_S | 0.736 | 0.880 | -0.619 | 1.499 | 0.712 | ||

| ESG.Co_S | 0.934 | -1.171 | -0.568 | 2.105 | 1.000 |

| Year | Measure | ESG.S_S | ESG.P_S | ESG.ML_S | ESG.F_S |

| 2018 | Quantization error | 0.374 | 0.030 | 0.152 | 0.179 |

| Topographic error | 0.131 | 0.028 | 0.076 | 0.130 | |

| (% explained variance) | 90.63 | 98.50 | 94.94 | 94.02 | |

| 2019 | Quantization error | 0.377 | 0.032 | 0.156 | 0.178 |

| Topographic error | 0.135 | 0.024 | 0.094 | 0.081 | |

| (% explained variance) | 90.56 | 98.42 | 94.81 | 94.07 | |

| 2020 | Quantization error | 0.382 | 0.033 | 0.157 | 0.188 |

| Topographic error | 0.122 | 0.012 | 0.100 | 0.085 | |

| (% explained variance) | 90.45 | 98.36 | 94.77 | 93.73 | |

| 2021 | Quantization error | 0.389 | 0.036 | 0.164 | 0.194 |

| Topographic error | 0.154 | 0.026 | 0.086 | 0.096 | |

| (% explained variance) | 90.28 | 98.25 | 94.53 | 93.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).