Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

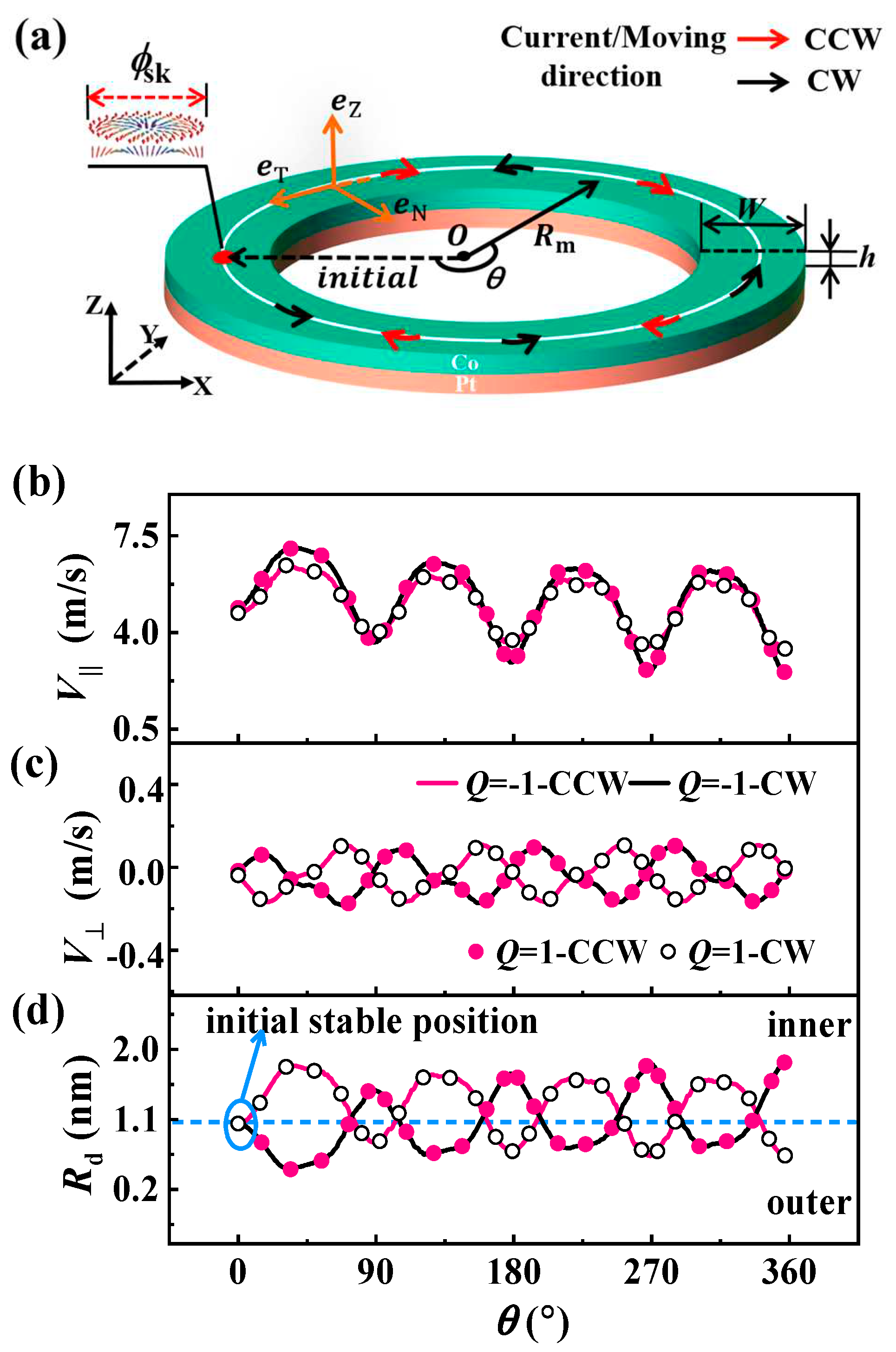

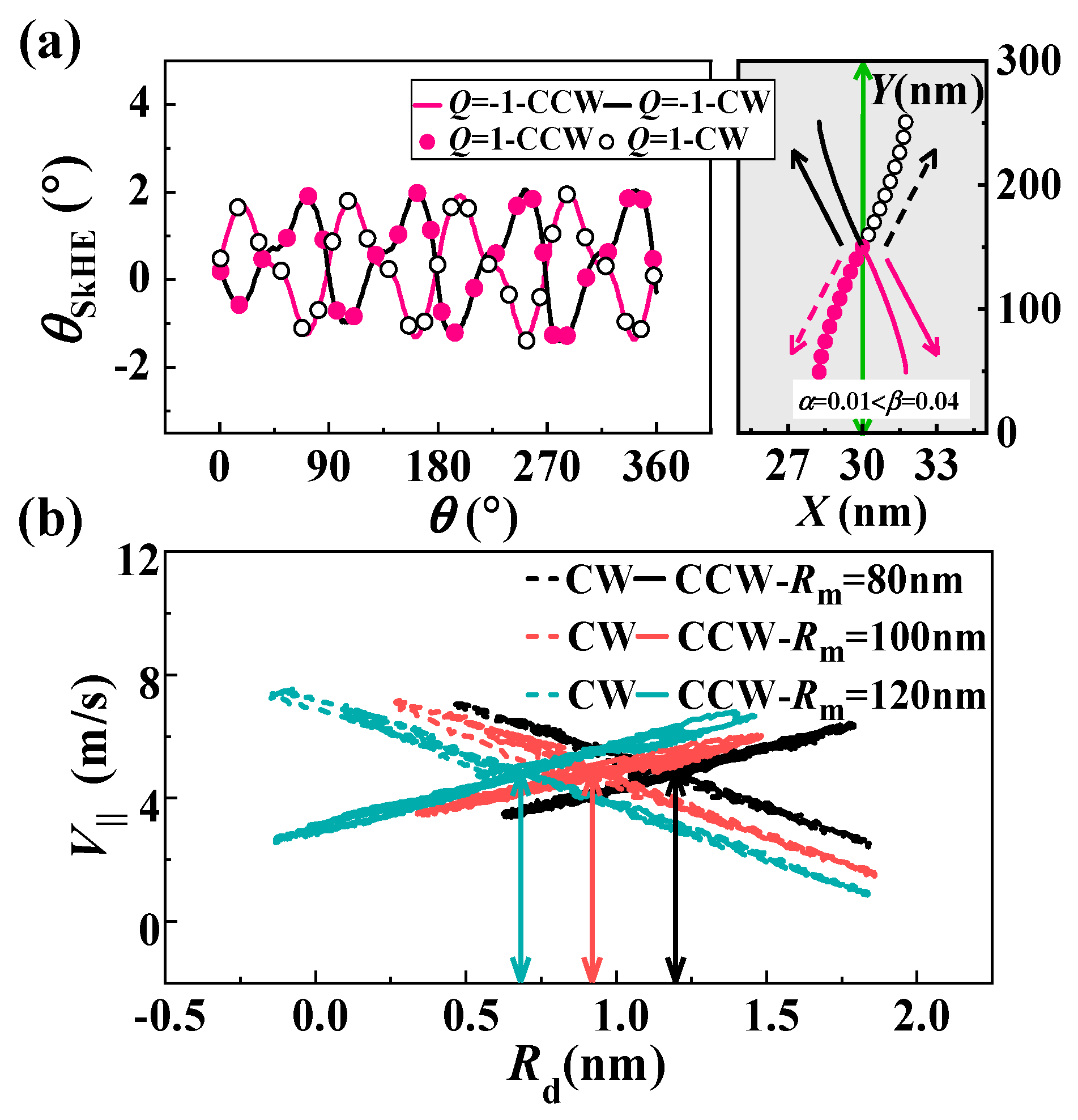

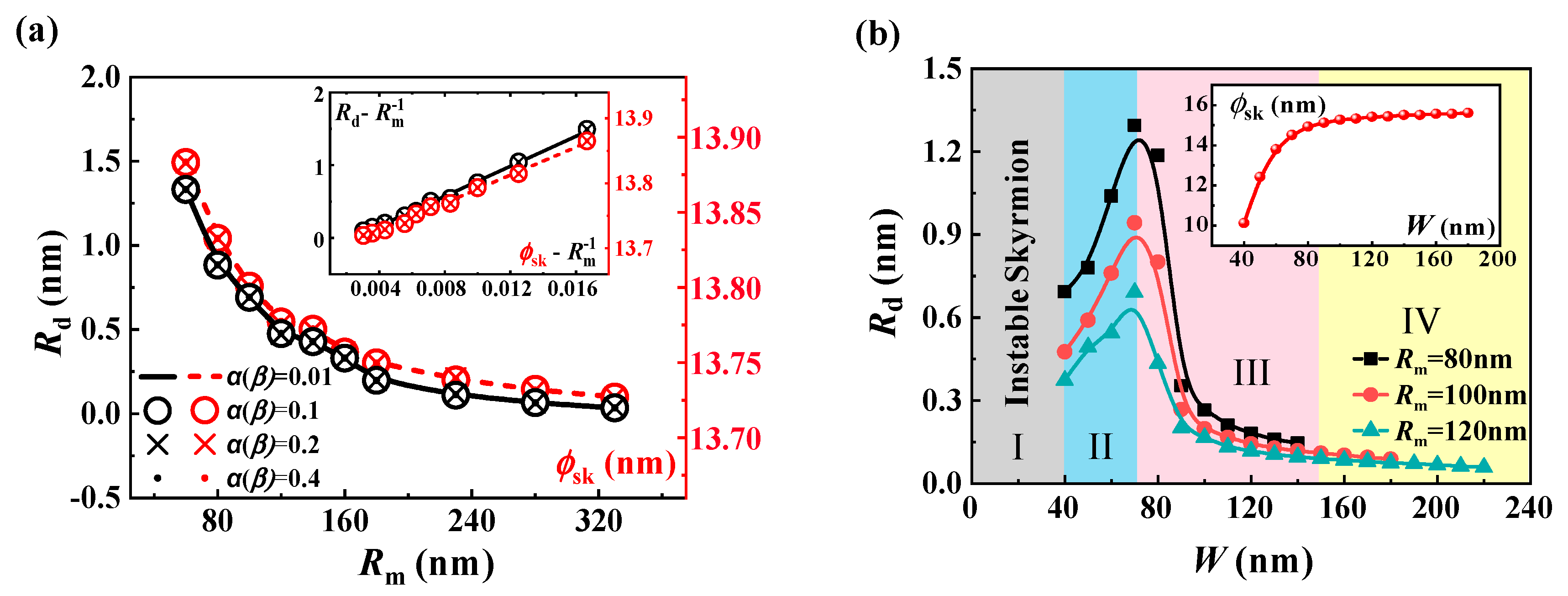

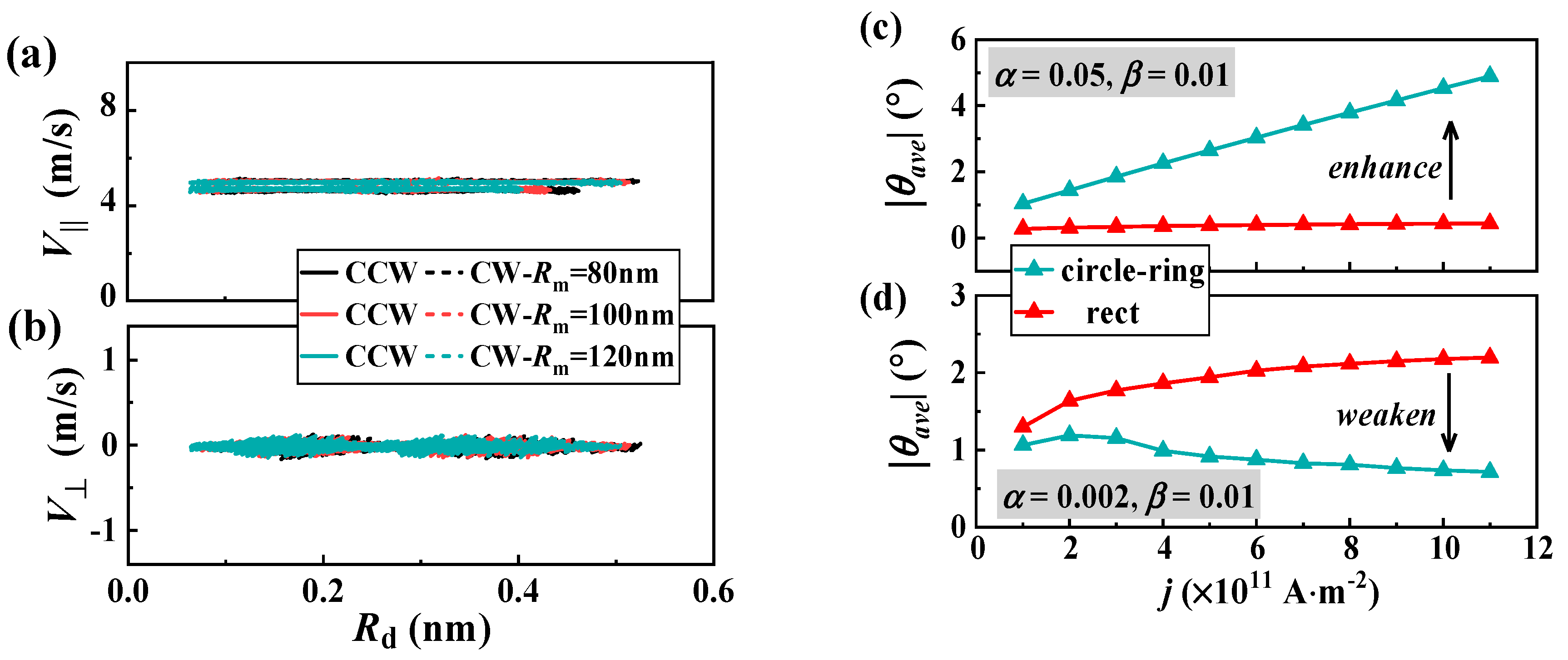

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rossler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature, 2006, 442, 797. [CrossRef]

- Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol., 2013, 8(12), 899. [CrossRef]

- Kravchuk, V.P.; Rossler, U.K.; Volkov, O.M.; Sheka, D.D.; van den Brink, J.; Makarov, D.; Fuchs, H.; Fangohr, H.; Gaididei, Y. Topologically stable magnetization states on a spherical shell: Curvature-stabilized skyrmions. Phys. Rev. B, 2016, 94(14), 144402. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Song, D.; Wei, W.; Nan, P.; Zhang, S.; Ge, B.; Tian, M.; Zang, J.; Du, H. Electrical manipulation of skyrmions in a chiral magnet. Nat. Commun., 2022, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Sepúlveda, S.; Vélez, J.A.; Corona, R.M.; Carvalho-Santos, V.L.; Laroze, D.; Altbir, D. Skyrmion dynamics in a double-disk geometry under an electric current. Nanomaterials, 2022, 12(18), 3086.

- Woo, S.; Litzius, K.; Kruger, B.; Im, M.Y.; Caretta, L.; Richter, K.; Mann, M.; Krone, A.; Reeve, R.M.; Weigand, M.; Agrawal, P.; Lemesh, I.; Mawass, M.A.; Fischer, P.; Klaui, M.; Beach, G.S. Observation of room-temperature magnetic skyrmions and their current-driven dynamics in ultrathin metallic ferromagnets. Nat. Mater., 2016, 15(5), 501. [CrossRef]

- Boulle, O.; Vogel, J.; Yang, H.; Pizzini, S.; de Souza Chaves, D.; Locatelli, A.; Mentes, T.O.; Sala, A.; Buda-Prejbeanu, L.D.; Klein, O.; Belmeguenai, M.; Roussigne, Y.; Stashkevich, A.; Cherif, S.M.; Aballe, L.; Foerster, M.; Chshiev, M.; Auffret, S.; Miron, I.M.; Gaudin, G. Room-temperature chiral magnetic skyrmions in ultrathin magnetic nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol., 2016, 11(5), 449. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Upadhyaya, P.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Kim, S.K.; Fan, Y.; Wong, K.L.; Tserkovnyak, Y.; Amiri, P.K.; Wang, K.L. Room-Temperature Creation and Spin-Orbit Torque Manipulation of Skyrmions in Thin Films with Engineered Asymmetry. Nano Lett, 2016, 16(3), 1981. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Jenkins, A.; Ma, X.; Razavi, S.A.; He, C.; Yin, G.; Shao, Q.; He, Q.L.; Wu, H.; Li, W.; Jiang, W.; Han, X.; Li, X.; Bleszynski Jayich, A.C.; Amiri, P.K.; Wang, K.L. Room-Temperature Skyrmions in an Antiferromagnet-Based Heterostructure. Nano Lett, 2018, 18(2), 980. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, J.; Cros, V.; Rohart, S.; Thiaville, A.; Fert, A. Nucleation, stability and current-induced motion of isolated magnetic skyrmions in nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol., 2013, 8(11), 839. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, J.; Mochizuki, M.; Nagaosa, N. Current-induced skyrmion dynamics in constricted geometries. Nat. Nanotechnol., 2013, 8(10), 742. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ezawa, M. A reversible conversion between a skyrmion and a domain-wall pair in a junction geometry. Nat Commun, 2014, 5, 4652. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Wei, Z.J.; Tu, H.R.; Zhang, C.H.; Hou, Z.P. Electric field manipulation of magnetic skyrmions. Rare Metals, 2022, 41(12), 4000. [CrossRef]

- Jonietz, F.; Mühlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Neubauer, A.; Munzer, W.; Bauer, A.; Adams, T.; Georgii, R.; Boni, P.; Duine, R.A.; Everschor, K.; Garst, M.; Rosch, A. Spin transfer torques in MnSi at ultralow current densities. Science, 2010, 330(6011), 1648. [CrossRef]

- Fert, A.; Cros, V.; Sampaio, J. Skyrmions on the track. Nat. Nanotechnol., 2013, 8(3), 152. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Kanazawa, N.; Zhang, W.Z.; Nagai, T.; Hara, T.; Kimoto, K.; Matsui, Y.; Onose, Y.; Tokura, Y. Skyrmion flow near room temperature in an ultralow current density. Nat. Commun., 2012, 3, 988. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Zhu, D.Q.; Kang, W.; Zhang, Y.G.; Zhao, W.S. Stochastic computing implemented by skyrmionic logic devices. Phys. Rev. Appl., 2020, 13(5), 054049. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-Q.; Chen, J.-P.; Tan, Z.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.-F.; Li, W.-A.; Gao, X.-S.; Liu, J.-M. Manipulation of skyrmion motion dynamics for logical device application mediated by inhomogeneous magnetic anisotropy. Nanomaterials, 2022, 12(2), 278. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. Skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Phys., 2017, 13(2), 112.

- Göbel, B.; Mertig, I. Skyrmion ratchet propagation: utilizing the skyrmion Hall effect in AC racetrack storage devices. Sci. Rep., 2021, 11(1), 3020. [CrossRef]

- Shigenaga, T.; Leonov, A.O. Harnessing skyrmion Hall effect by thickness gradients in wedge-shaped samples of cubic helimagnets. Nanomaterials, 2023, 13(14), 2073. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Pong, P.W.T.; Zhou, Y. Elimination of the skyrmion Hall effect by tuning perpendicular magnetic anisotropy and spin polarization angle. Phys. Lett. A, 2022, 456, 128497. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.F.; Wang, J.B.; Zheng, Q.; Zhu, Q.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Chen, S.J.; Jin, C.D.; Liu, Q.F.; Jia, C.L.; Xue, D.S. Current-induced magnetic skyrmions oscillator. New J. Phys., 2015, 17(2), 023061. [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.S.; Lee, K.J. Magnetic skyrmion field-effect transistors. Appl. Phys. Lett., 2019, 115(7), 072406. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Qin, R.; Zheng, Y.-Q.; Wang, Y. Skyrmion Hall effect with spatially modulated Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction. Front. Phys., 2019, 14(5), 536021. [CrossRef]

- Whang, H.S.; Choe, S.B. Spin-Hall-effect-modulation skyrmion oscillator. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1), 11977. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.L.; Zhao, R.Z.; Ji, L.Z.; Chen, W.C.; Bandaru, S.; Zhang, X.F. A universal law for predicting the motion behaviors of skyrmions under spatially-varying strain field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater., 2020, 513, 166954. [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.K.C.; Ho, P.; Lourembam, J.; Huang, L.; Tan, H.K.; Reichhardt, C.J.O.; Reichhardt, C.; Soumyanarayanan, A. Visualizing the strongly reshaped skyrmion Hall effect in multilayer wire devices. Nat Commun, 2021, 12(1), 4252.

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, G.; Xiang, G. A skyrmion diode based on skyrmion Hall effect. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, 2022, 69(3), 1293. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Xia, J.; Zhang, X.C.; Zheng, X.Y.; Li, G.Q.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Yin, H.H.; Chantrell, R.; Xu, Y.B. Magnetic skyrmionium diode with a magnetic anisotropy voltage gating. Appl. Phys. Lett., 2020, 117(20), 202401. [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, W. Experimental Realization of a Skyrmion Circulator. Nano Lett., 2022, 22(23), 9638. [CrossRef]

- Castell-Queralt, J.; González-Gómez, L.; Del-Valle, N.; Sanchez, A.; Navau, C. Accelerating, guiding, and compressing skyrmions by defect rails. Nanoscale, 2019, 11(26), 12589. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M.-W.; Cros, V.; Kim, J.-V. Current-driven skyrmion expulsion from magnetic nanostrips. Phys. Rev. B, 2017, 95(18). [CrossRef]

- Al Saidi, W.; Sbiaa, R.; Bhatti, S.; Piramanayagam, S.N.; Al Risi, S. Dynamics of interacting skyrmions in magnetic nano-track. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 2023, 56(35), 355001. [CrossRef]

- Paikaray, B.; Kuchibhotla, M.; Haldar, A.; Murapaka, C. Skyrmion based majority logic gate by voltage controlled magnetic anisotropy in a nanomagnetic device. Nanotechnology, 2023, 34(22), 225202. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Li, Q.; Xia, J.; Lai, P.; Hou, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G. Realization of the skyrmionic logic gates and diodes in the same racetrack with enhanced and modified edges. Appl. Phys. Lett., 2022, 121(4). [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.-H.; Han, H.-S.; Kim, N.; Kim, G.; Jeong, S.; Lee, S.; Kang, M.; Im, M.-Y.; Lee, K.-S. Magnetic skyrmion diode: Unidirectional skyrmion motion via symmetry breaking of potential energy barriers. Phys. Rev. B, 2021, 104(6), L060408. [CrossRef]

- Morshed, M.G.; Vakili, H.; Ghosh, A.W. Positional Stability of Skyrmions in a Racetrack Memory with Notched Geometry. Phys. Rev. Appl., 2022, 17(6), 064019. [CrossRef]

- Gaididei, Y.; Kravchuk, V.P.; Sheka, D.D. Curvature effects in thin magnetic shells. Phys. Rev. Lett., 2014, 112(25), 257203. [CrossRef]

- Streubel, R.; Fischer, P.; Kronast, F.; Kravchuk, V.P.; Sheka, D.D.; Gaididei, Y.; Schmidt, O.G.; Makarov, D. Magnetism in curved geometries. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 2016, 49(36), 363001. [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, A.; Leliaert, J.; Dvornik, M.; Helsen, M.; Garcia-Sanchez, F.; Van Waeyenberge, B. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP. Adv., 2014, 4(10), 107133. [CrossRef]

- Leliaert, J.; Dvornik, M.; Mulkers, J.; De Clercq, J.; Milošević, M.V.; Van Waeyenberge, B. Fast micromagnetic simulations on GPU—recent advances made with MuMax3. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 2018, 51(12), 123002.

- Je, S.G.; Thian, D.; Chen, X.; Huang, L.; Jung, D.H.; Chao, W.; Lee, K.S.; Hong, J.I.; Soumyanarayanan, A.; Im, M.Y. Targeted Writing and Deleting of Magnetic Skyrmions in Two-Terminal Nanowire Devices. Nano Lett, 2021, 21(3), 1253. [CrossRef]

- Koshibae, W.; Kaneko, Y.; Iwasaki, J.; Kawasaki, M.; Tokura, Y.; Nagaosa, N. Memory functions of magnetic skyrmions. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., 2015, 54(5), 053001. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.C.; Xia, J.; Zhao, G.P.; Liu, X.X.; Zhou, Y. Magnetic skyrmion transport in a nanotrack with spatially varying damping and non-adiabatic torque. IEEE Trans. Magn., 2017, 53(3), 1500206. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kang, W.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, X.; Lei, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, W. Skyrmion dynamics in width-varying nanotracks and implications for skyrmionic applications. Appl. Phys. Lett., 2017, 111(20), 202406. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, G.P.; Fangohr, H.; Liu, J.P.; Xia, W.X.; Xia, J.; Morvan, F.J. Skyrmion-skyrmion and skyrmion-edge repulsions in skyrmion-based racetrack memory. Sci Rep, 2015, 5, 7643. [CrossRef]

- Gorshkov, I.O.; Gorev, R.V.; Sapozhnikov, M.V.; Udalov, O.G. DMI-gradient-driven skyrmion motion. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater., 2022, 4(7), 3205. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).