1. Introduction

The Hepatitis B (HepB) virus, the second most important known human carcinogen, chronically infects over 240 million persons worldwide.1 This can be transmitted vertically and horizontally and can ultimately result in premature death from cancer or liver cirrhosis. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 4 to 5 million lives globally each year are saved because of vaccination, and the hepatitis B vaccine is no exception.2 It not only protects against HepB infection in adults and children, but is 90% effective in preventing perinatal transmission if the first dose in given within the first 24 hours of life, followed by a minimum of 2 subsequent doses.

Development of chronic disease can be predicted based on age of acquisition of the HepB virus, with a risk of 90% if acquired in the perinatal period, 30 to 60% in early childhood, 5 to 10% ages 5 to 20 years and 1-5% in adults over 20 years.3

The elimination of mother to child transmission (EMTCT) plus initiative has within its framework steps to eliminate not only Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Syphilis, but also HepB and Chagas disease. In December 2017, Antigua and Barbuda was validated by the World Health Organization Validation Advisory Committee (GVAC) as having eliminated mother to child transmission of HIV and Syphilis, with validation status being maintained in 2019 and 2020 when last reviewed in 2022 communicated via email (R. Thomas 2023, personal communication, 12th April).4 The EMTCT plus initiative is therefore the next step for the twin island state with particular emphasis on triple elimination (HIV, Syphilis and HepB). At the Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre from 2020 to 2022, 26 mothers were tested positive for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) of the 3160 mothers of live births of the aforementioned years; which is equivalent to a prevalence rate of 0.8% [A.King 2023, personal communication, 27th September].

Chronic hepatitis B infections have a prevalence rate of 0.33% (0.26 to 0.95%) in Latin America and the Caribbean affecting 2.1 million persons, of which more than 13,000 deaths are estimated to occur annually from HBV and related disease.5 Perinatal transmission characterized 56% of the cases in 2016, therefore important strides must be made not only in ensuring universal hepatitis B vaccination coverage but also in instituting a universal birth dose policy.

The World Health Assembly in 2016 endorsed the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat to include elimination of mother to child transmission of hepatitis B by 2030.6 Validation of the latter through the WHO, for countries that provide universal Hepatitis B vaccine at birth, requires ≥90% coverage with the birth dose and ≥ 90 % coverage with 3 doses of the hepatitis B vaccine (HepB3) in infants ; with maintenance of these targets for at least 2 years.7 The impact of these targets is also monitored in order to achieve validation, which means that countries should achieve a ≤ 0.1% HBsAG prevalence among children ≤ 5 years. The local framework for determining and tracking the HBsAg of children ≤ 5 years old remains in its embryonic stage and requires further discussion and planning.

Antigua and Barbuda a twin island state in the Caribbean joined St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Lucia, Dominica and Grenada in instituting a universal HepB-BD program.8 With a population of 97, 928 , Antigua and Barbuda has one primary public hospital, the Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre (SLBMC), with just over 1000 deliveries annually that offers both routine and critical newborn care; managing neonates of gestational ages of 26 weeks and above.9 As the country’s primary facility, it accounts for over 97% of births, with only one private facility at the time of publication offering delivery services (R. Mansoor 2023, personal communication, 25th September]. In 2021 the SLBMC accounted for 99.5% of the nation’s live births. The Hepatitis B vaccine – the birth dose (HepB-BD) was introduced on October 11th 2021 at the Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre. The vaccine is procured by the government of Antigua and Barbuda through the Pan American Health Organization’s Revolving Fund and through the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations. Vaccines are offered to the public free of cost. Prior to the program’s formal introduction it was ensured that an institutional policy) was prepared and implemented with the necessary logistics put in place regarding vaccination storage and logging post administration. Staff were then oriented to the policy and trained on key topics to include the rationale for the HepB-BD, the crucial importance of timing administration and documentation, the revised immunization schedule, the importance of maintaining the cold and the quality assurance steps that would be implemented. Staff training took place within the hospital and primary health care facilities, included public and private health care providers and facilitated the distribution of health care worker educational guides. Client education was primarily facilitated on an individualized basis during antenatal visits given the marked misinformation that already existed surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine, leading to a general milieu of vaccine hesitancy. Mass media educational drives were avoided. A client brochure was also prepared to better enable the educational process. This was given to the client either during their antenatal visit, or while at birthing facility.

The national Maternal Child and Adolescent policy manual offers guidance that all pregnant women should have their HBsAg status assessed and documented in the first and third trimester which enables the appropriate management being instituted antenatally and postnatally.10

1.1. Definitions1:

Timely birth dose coverage: the proportion of live births who receive a HepB-BD within 24 hours after birth. All doses given on day 0 or 1 of life meet this definition (i.e. the date of delivery and the day following delivery). This is the global standard for monitoring HepB-BD coverage.

Total birth dose coverage: the proportion of live births who receive any HepB-BD, defined as those vaccinated any time up until the first dose is due, or as per country guidance on upper age range.

Health facility birth dose coverage: the proportion of live births in a health facility who receive HepB-BD. This may be tracked separately if there are different coverage targets for facility births, especially regarding timely birth dose administration.

Home birth dose coverage: the proportion of live home births who receive HepB-BD. This section outlines the methods for monitoring and evaluating a HepB-BD vaccination

The denominator used for calculating coverage was number of live births.

1.2. Rationale:

Given the rapid startup of the Hepatitis B vaccine birth dose program in a vaccine hesitant milieu, and the absence of a mass media educational drive, there are likely quality gaps that exist which would negatively impact vaccine uptake and timely administration. A review would therefore seek to establish vaccination rates and outline quality improvement steps that can be taken in order to improve indicators of interest

1.3. Objectives:

Review timeliness of HepB-BD administration at the SLBMC

- 5.

Review the uptake of the HepB-BD at the SLBMC, capturing the reasons for refusal

- 6.

Outline recommendations for quality improvement for the HepB-BD program

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods:

Post implementation of the HepB-BD vaccination program in October 2021, data to include date and time of birth, date and time of administration of the vaccine, batch number and expiration date were captured in a log book at the program’s inception. Data was entered into the vaccination log book by the healthcare provider who administered the vaccine immediately post administration. Consent was attained verbally before the vaccine was administered. This was usually attained after birth. Mothers who delivered at home or whose babies were born before arrival (BBA) were consented on arrival to hospital whilst receiving care. The consent of minors; the age of consent being 16 was primarily done in the presence of their guardians however this was not formally addressed in the hospital’s vaccination policy.11 If the vaccine was refused, the reason for refusal was documented in the newborns chart. When a newborn was seen by a clinician on a daily basis, if the vaccine was refused then this was added to a refusal list as an item void of patient identifying details to include reason for refusal. At the end of each month, total number of vaccines administered and the tally of refusals were added and compared to the number of live births from the log book of births and deaths assigned to the maternity ward. This enabled capturing any missed doses. Maternal age and route of delivery were also captured from the maternity ward’s log book. Mother’s Hepatitis B status was also noted from the Perinatal Information System form. Data was collected from November 2021 to October 2022.

Inclusion Criteria – Newborns delivered at SLBMC

Exclusion criteria - Newborns who are birthweight < 2000g for mother with negative HBsAg.

2.2. Data Analysis:

Data are presented as frequencies, and percentages, with the primary measure being captured as the proportion of live births who received the HepB-BD within 24 hours of birth, and the secondary measure captured as the proportion of livebirths who received the HepB-BD within 14 days of life as per country protocol. Factors influencing timely versus untimely administration were analyzed through use of Odds Ratio.

2.3. Ethics:

Ethical approval was sought through the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of SLBMC and the IRB of the Ministry of Health Wellness Social Transformation and the Environment (MOHWE). Patient interviews will not be conducted. It is important to note that even though the Hepatitis B vaccine is administered as part of newborn care, consent must be received by the health care provider before same is administered; however that which is being audited is the log book. Since the log book had patient identifiable information, then it was stored in the unit manager’s office in a locked cupboard. The data collected and processed as outlined in the indicators above had no patient identifying information. This will be stored in a password protected computer on the maternity ward for 2 years.

3. Results

The study period of November 2021 to October 2022 was characterized by 924 live births at the SLBMC which accounted for 98.5% (n=938) of national live births over the study period. Of the live births at SLBMC 4.3% (n=40) weighed less than 2000 grams. Further analysis revealed that 99.7% were facility born, and 0.3% were born before arrival (BBA).

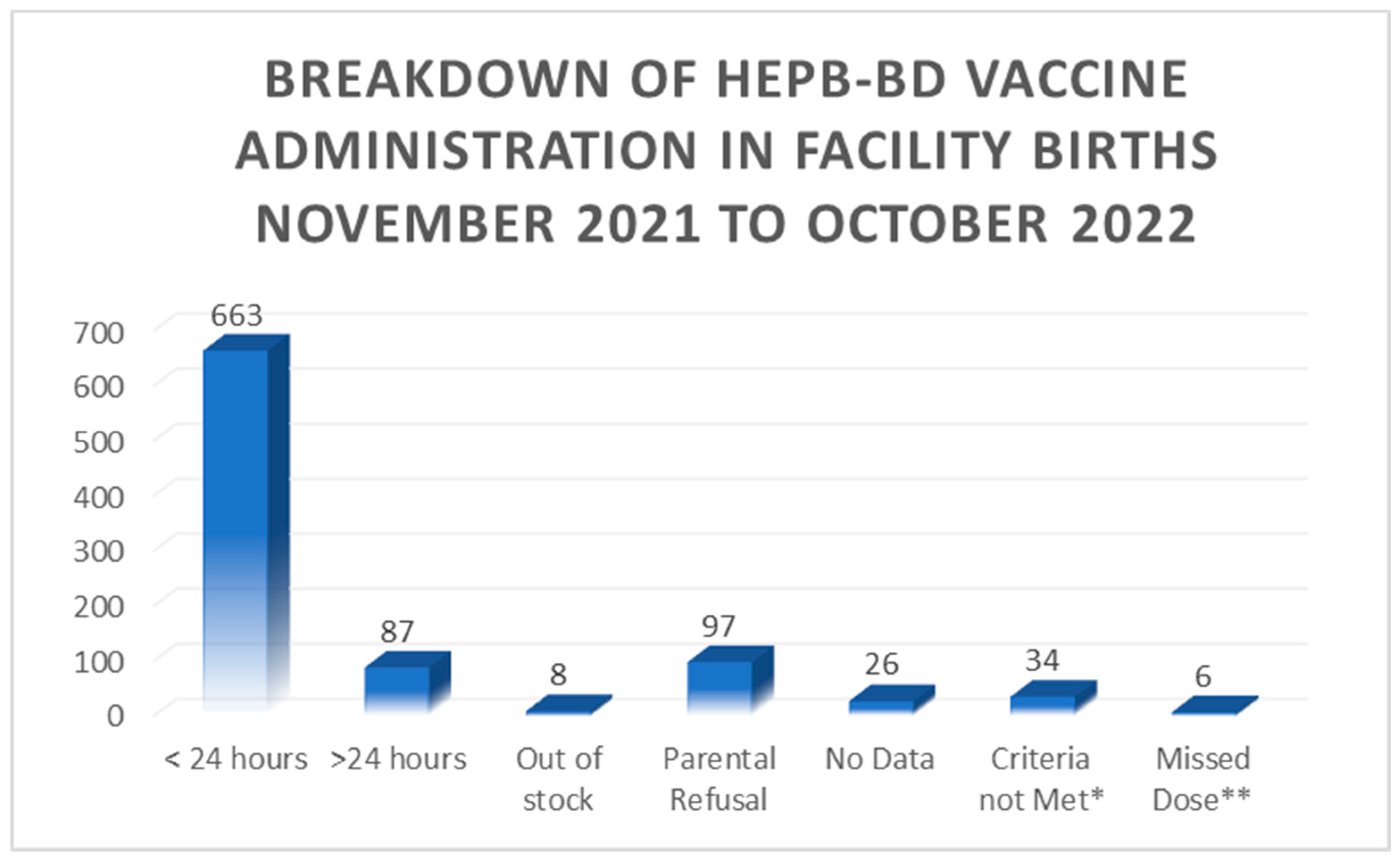

Of the babies born at the SLBMC i.e. facility births, further details regarding vaccine availability and administration are demonstrated in

Figure 1.0 below:

Notably, 100% of babies BBA received the vaccine within < 24 hours of birth. Overall 72% of live births received timely administration of the HepB-BD whilst total birth dose coverage was 81% of live births. The maximum duration of time from birth to vaccination administration was 11 days 4 hours and 55 minutes.

3.1. Parental Refusal

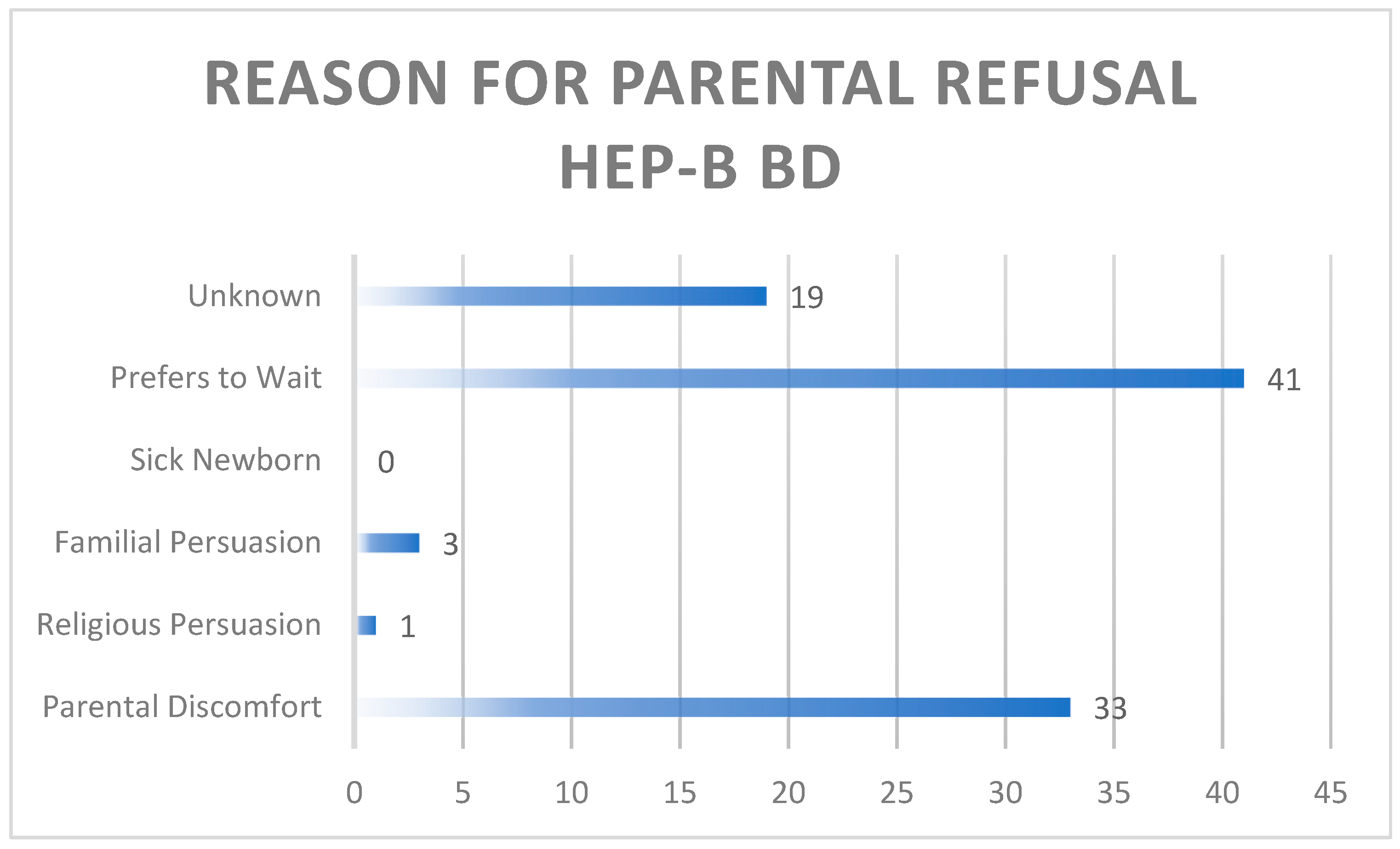

Parental consent was routinely attained by the physician or nursing staff as per policy, prior to the administration of the HepB-BD. 10.5% of parents refused the HepB-BD. Issues raised at the time of consent that impacted refusal were classified and documented as follows: parental discomfort with the vaccine to include lack of sufficient knowledge, familial persuasion against vaccine administration, having a sick newborn, religious persuasion, unknown reason and the desire to wait until 2 months of age.

Figure 2.0 demonstrates the aforementioned reasons for refusal.

Figure 2.0. Rationale for parental refusal of HepB-BD.

3.2. Maternal Hepatitis B Status

The maternal HBsAg status was reviewed prior to vaccination of the newborn. It is important to note that the status captured was at the time of vaccination administration and doesn’t reflect maternal results that were subsequently followed if the mother’s status at the time was unknown. A documented Maternal HBsAg result was available for 90.4% of mothers of this cohort.

Table 1 below demonstrates the HepB-BD receipt frequency by Maternal HBsAg status.

A positive maternal HBsAg result triggered the administration of both the HepB vaccine and the Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG). Of the 6 babies born to HBsAg mothers all received the HepB-BD - one baby in just over 24 hours and all others in < 12 hours. In 83% (5/6) of the exposed newborns the Hepatitis B Immunoglobulin was administered in < 12 hours; whilst one exposed baby was unable to receive the Immunoglobulin as it was unavailable.

3.3. Factors influencing administration

Factors associated with administration of the vaccine are demonstrated in

Table 2 below. Babies born to mothers < 35 years of age who received timely administration of the vaccine had an odds ratio 1.79 times that of babies born to mothers ≥ 35 years who received the vaccine in a timely manner. Note should be made however that other confounders were not controlled for to include maternal highest educational level, parity, and socio-economic status. This could be addressed through design adjustments to include randomization, restriction or establishing a selection criterion. There was no statistically significant difference in the odds of receiving the vaccine in a timely manner on the weekend or in the week. Babies born via vaginal delivery who received the vaccine in a timely manner had an odds ratio that was 12.2 times that of babies born via C-section who received a timely dose; this was statistically significant. It should be noted however that vaginal delivery is the primary route of delivery (79% of deliveries) and therefore could contribute to confounding error. In a review of ‘Factors associated with receipt of a timely infant birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine at a tertiary hospital in North-Central Nigeria” by Bada, F.O., et al., (2022) maternal factors such as parity, marital status or educational status had no significant impact on the timely administration of the HepB-BD.

12

Review of the processes that govern the administration of the HepB-BD post a C-section delivery however is warranted, as the timing of consent can potentially be delayed due to recovery time and other competing priorities that may occur immediately post C-section.

4. Discussion

4.1. Timeliness

There has been progress globally in the fight of eliminating MTCT of Hepatitis B as >98% World Health Assembly member states have introduced a universal infant hepatitis B vaccination program.

6 Despite this, the introduction of the HepB-BD into routine immunization programs has much to be desired as in 2020 only 57% of these countries provided the HepB-BD routinely to all newborns, with its timely administration ranging from 37 to 43% in 2016 to 2020.

8 The Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre, having achieved a timely birth dose of 72% during the time period of this audit is commendable, however more work is required to achieve the 2021 programmatic target of WHO of having ≥90% timely HepB-BD national immunization coverage. The total birth dose coverage at the time of this audit was 81%, however during 2016 to 2020 of the global countries that reported, 51 – 58% of them confirmed a HepB-BD coverage rate of > 90%.

6 The HepB-B3 coverage of > 90% is also a crucial target, though not formally reviewed in this audit, it is crucial to mention. In 2021, in the Region of the Americas, the HepB3 coverage in children under the age of 1 was 81%, with Antigua and Barbuda reporting 92% coverage.

13,14 Table 3 below aptly reflects timely birth coverage and HepB3 coverage for the various Regions.

4.2. Barriers/education

4.2.1. Client level

Parental hesitancy remains a crucial factor that needs to be addressed. Of the parents who refused the vaccine 76% either felt uncomfortable or preferred to wait. The legal right of parents to refuse vaccines must always be considered, however further exploration of these concerns are vital in informing future educational efforts, which need to be a more robust capturing not only expectant families during the antenatal period but also their primary support system. These programs may include public service announcements, WhatsApp blasts, social media campaigns town halls, a hotline, discussions in antenatal classes, radio and tv programs and newspaper articles which can clearly state facts and address common misconceptions. The power of community based educational initiatives should not be overlooked.

16 Strengths of this program included the availability of pamphlets for families as well as the availability of a staff handout which served as a standard guide to answer frequently asked questions. It is recognized that local experience can be used to guide strategy, as that which is given by WHO serves as a starting point [

16]. That which transpired in neighboring and comparable settings should also be reviewed and used as a guide.

16

Three factors are included in the WHO vaccine hesitancy model: confidence ( in vaccine or provider), complacency (need for and value of vaccine not appreciated), and convenience (barriers to access to vaccines) .17 Lack of confidence and complacency are likely two factors that impacted our program.

The milieu at the time of the roll out of this program in 2021 should be considered. The COVID-19 pandemic has generally changed parents intention to vaccinate their children.17 Covid-19 was thought to have a heterogenous impact on vaccination in countries across the region; with 15 countries in 2020 and 2021 reporting their lowest HepB-B3 coverage in the previous 10 years.8,13 That compounded with the historical fact that in Antigua and Barbuda the HepB-Bd was only selectively given to the hepatitis B exposed infant with first vaccines otherwise being administered at 2 months of age, could have influenced one’s desire to wait.

Transitioning to having a standing order instituted where the vaccine is not given if there is a true indication or where the parent ‘opts out’ may be a step that needs to be considered. Having improved from 73 to 84%. In the Philippines hospitals with a standing order were 4.8 (CI 1.2 – 18) times more likely to have more than 50% coverage – findings however were limited as no control for confounders was made.18

4.2.3. Facility level

Staff training and having a written policy were assets to this program, however there were missed opportunities for vaccine administration. A gap identified is the vaccination of babies < 2000g whose maternal Hep B status was unknown. Moturi, E., et al., (2018) in reviewing the knowledge attitudes and practices regarding the implementation of the birth dose of the Hepatitis B vaccine in five African countries found that most staff had suboptimal knowledge regarding the age limits and contraindications of the HepB-BD.19 Conducting refresher training courses that incorporate gaps identified are useful and should include health care professionals in public and private practice.16 Continuous data sharing of that which is ascertained through monitoring and evaluation of the program is crucial.

Antigua and Barbuda subscribes to GAVI and the PAHO revolving fund, which is a crucial step in ensuring a reduced likelihood in the interruption of the supply chain of vaccines. During the timeframe of this audit, 0.9% of babies were unable to receive the HepB-BD due to the vaccine being out of stock. Disruptions in the supply chain for vaccines of the WHO Expanded Program on Immunization due to the Covid-19 pandemic even is concerning, even as it impacts developing countries.20 This concern continues in the post pandemic era.

Adverse health outcomes potentially related to HepB-BD administration should continually be monitored by the hospital’s surveillance unit with subsequent reporting to the surveillance unit for the MOHWE. This should be clearly outlined in the hospital and national policy so that the mechanism of reporting is clear.21

Recommendations therefore include instituting innovative educational sessions that capture parental concerns in the local context, implementing recertification programs for staff, and a quality improvement team that reviews timely birth dose and total birth dose coverage with monthly or quarterly targets in place. Utilizing a database /health information system will strengthen monitoring and evaluation of the program. Formalizing a national policy that governs not only the public hospital but private institutions as well, as this is crucial and will help inform/regulate the process of reporting from private facilities. The sustainability of this program is heavily dependent on leadership and governance; ensuring a consistent vaccine supply chain through regional and international partnership and implementing the necessary framework that supports monitoring the targets and the impact necessary for validation of HepB elimination. This should fall under the purview of the Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Committee of the Ministry of Health, Wellness, the Environment and Social Transformation.

5. Conclusion

The Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre has achieved a timely HepB-BD coverage of 72% and total birth dose coverage of 81% from November 2021 to October 2022. This is a commendable start within the first year of this vaccine’s roll out despite the milieu of vaccine hesitancy. With continued improvement in client educational campaigns, staff refresher courses with emphasis on gaps identified, processes that govern administration post Cesarean section and possible implementation of a standing order approach re vaccination administration within 24 hours post-delivery; timely birth dose coverage and total birth dose coverage will likely improve. This will put the twin island state in good stead as we journey toward elimination of MTCT of hepatitis B.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization S.B.J.; methodology S.B.J., and S.S.; validation S.B.J. and T.F.L, resources S.B.J; formal analysis S.B.J.; writing—original draft preparation S.B.J., writing—review and editing S.B.J., T.F.L., C,D.C.C, and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the version of the manuscript submitted for publication

Funding

This audit received no external funding.

Research in Context

Medline, PubMed, Semantic scholar and Cochrane databases were explored using the following key words: hepatitis b vaccine, birth dose, elimination of mother to child transmission, universal. MeSH terms Hepatitis B vaccine and Birth dose were utilized. The search was not limited by article type, but articles within a customized range of 15 years were used. Only Articles written in English were utilized.

Added Value

This manuscript highlights an added country on the path to triple elimination. By highlighting barriers faced and successes in a Caribbean context and clearly stating useful recommendations, this may aid other jurisdictions as they implement or strive to improve the universal newborn hepatitis b vaccine program. This will also help to improve the quality of current programs as well, and inform policy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were sought through the Institutional Review Boards of SLBMC and MOHWE. There was no risk of harm or distress to patients. This decision was relayed by the IRB of SLBMC and MOHWE on 23.12. 2021 and 14.03.2023 respectively.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as there was no direct patient contact but rather a review of the processes and standards surrounding the Hepatitis B Birth Dose administration process.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of the staff of the Sir Lester Bird Medical Centre and the Ministry of Health Wellness and the Environment.

References

- World Health Organization. Preventing perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission: a guide for introducing and strengthening hepatitis B birth dose vaccination.

- World Health Organization. (2019) Immunization. Available at Immunization (who.int) (Accessed 8 August2023).

- Awuku, Y.A.; Yeboah-Afihene, M. Hepatitis B at-birth dose vaccine: an urgent call for implementation in Ghana. Vaccines. 2018, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PAHO/WHO | Six Caribbean territories and states eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis. (Accessed 28 September 2023).

- Plus, P.E. Framework for elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, Syphilis, Hepatitis B, and Chagas; Pan American Health Organisation: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Khetsuriani, N.; Lesi, O.; Desai, S.; Armstrong, P.A.; Tohme, R.A. Progress Toward the Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus — Worldwide, 2016–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022, 71, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Interim guidance for country validation of viral hepatitis elimination.

- WHO. (2022). Introduction of HepB birth dose. Available at Introduction of HepB birth dose (who.int) (Accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Population, total- Antigua and Barbuda, Population, total - Antigua and Barbuda | Data (worldbank.org)(Accessed on December 8 2021).

- Ministry of Health Wellness and the, Environment. Maternal Child and Adolescent Health Manual, Antigua and Barbuda, 3rd ed.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Age of Consent in Antigua and Barbuda. (2023) Available at Antigua And Barbuda Age of Consent & Statutory Rape Laws (Accessed 28 September 2023).

- Bada, F.O.; Stafford, K.A.; Osawe, S.; Wilson, E.; Sam-Agudu, N.A.; Chen, H.; Abimiku, A.L.; Campbell, J.D. Factors associated with receipt of a timely infant birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine at a tertiary hospital in North-Central Nigeria. PLOS Global Public Health 2022, 2, e0001052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PAHO. (2022) EMTCT Plus Initiative 2010-2021. Available at2023-cde-4-etmi-plus-prev-mtct-childhood-hep-b.pdf (Accessed 7 August 2023).

- Immunization, HepB3 (% of one-year-old children) | Data (worldbank.org) (2023) (Accessed 7 August 2023).

- Introduction of Hepatitis B Birth dose vaccination in Africa: a toolkit for National Immunization Technical Advisory groups 2022. (2022) Available at HepB-BD NITAG toolkit final version_12-16-22_0-FINAL.pdf (globalhep.org) (Accessed 8 August 2023).

- Boisson, A.; Goel, V.; Yotebieng, M.; Parr, J.B.; Fried, B.; Thompson, P. Implementation approaches for introducing and overcoming barriers to hepatitis B birth-dose vaccine in sub-Saharan Africa. Global Health: Science and Practice 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, M.D.; Roberts, B.; Wong, B.L.; van Kessel, R.; Mossialos, E. The relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine hesitancy: a scoping review of literature until August 2021. Frontiers in public health 2021, 9. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Practices to improve coverage of the hepatitis B birth dose vaccine, World Health Organization, 2012.

- Moturi, E.; Tevi-Benissan, C.; Hagan, J.E.; Shendale, S.; Mayenga, D.; Murokora, D.; Patel, M.; Hennessey, K.; Mihigo, R. Implementing a birth dose of hepatitis B vaccine in Africa: findings from assessments in 5 countries. Journal of immunological sciences 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilo, T.M.; Endale, S.Z.; Demie, T.G.; Dinka, T.G. The impact of COVID-19 on supplies of routine childhood immunization in Oromia regional state, Ethiopia: A mixed method study. Risk management and healthcare policy 2022, 2343–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Maternal and neonatal immunization field guide for Latin America and the Caribbean; World Health Organization: Washington, DC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).