Submitted:

02 November 2023

Posted:

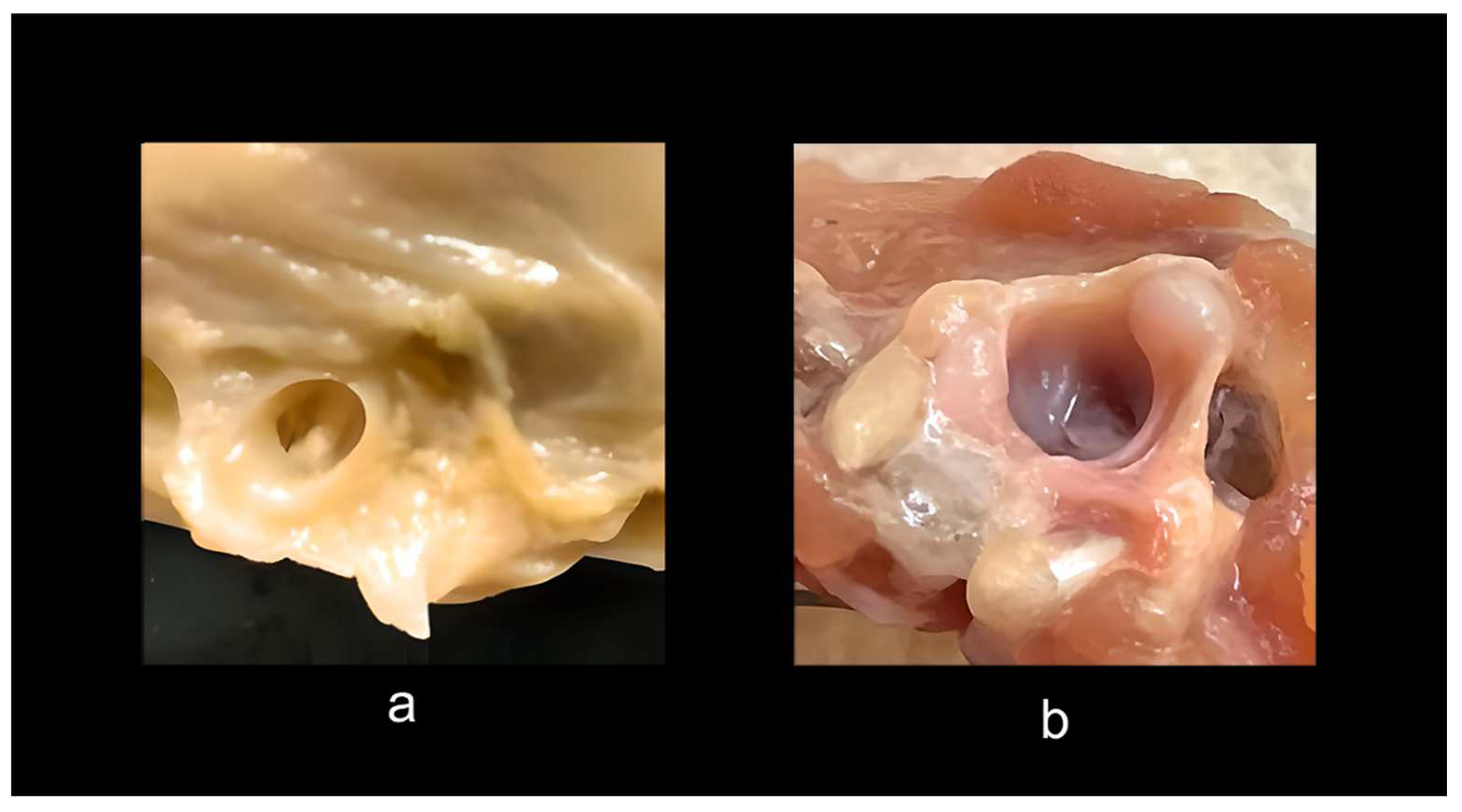

03 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

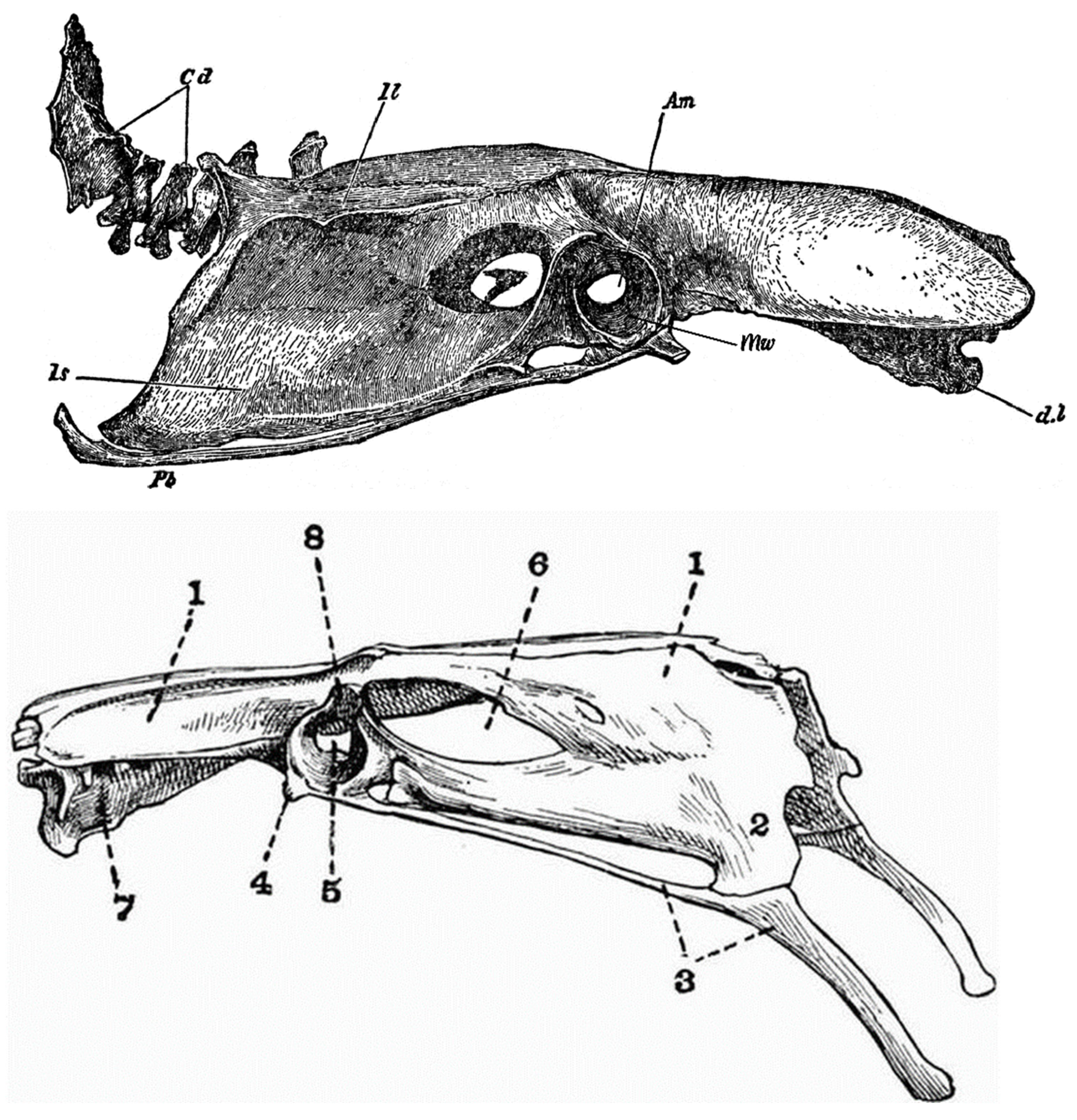

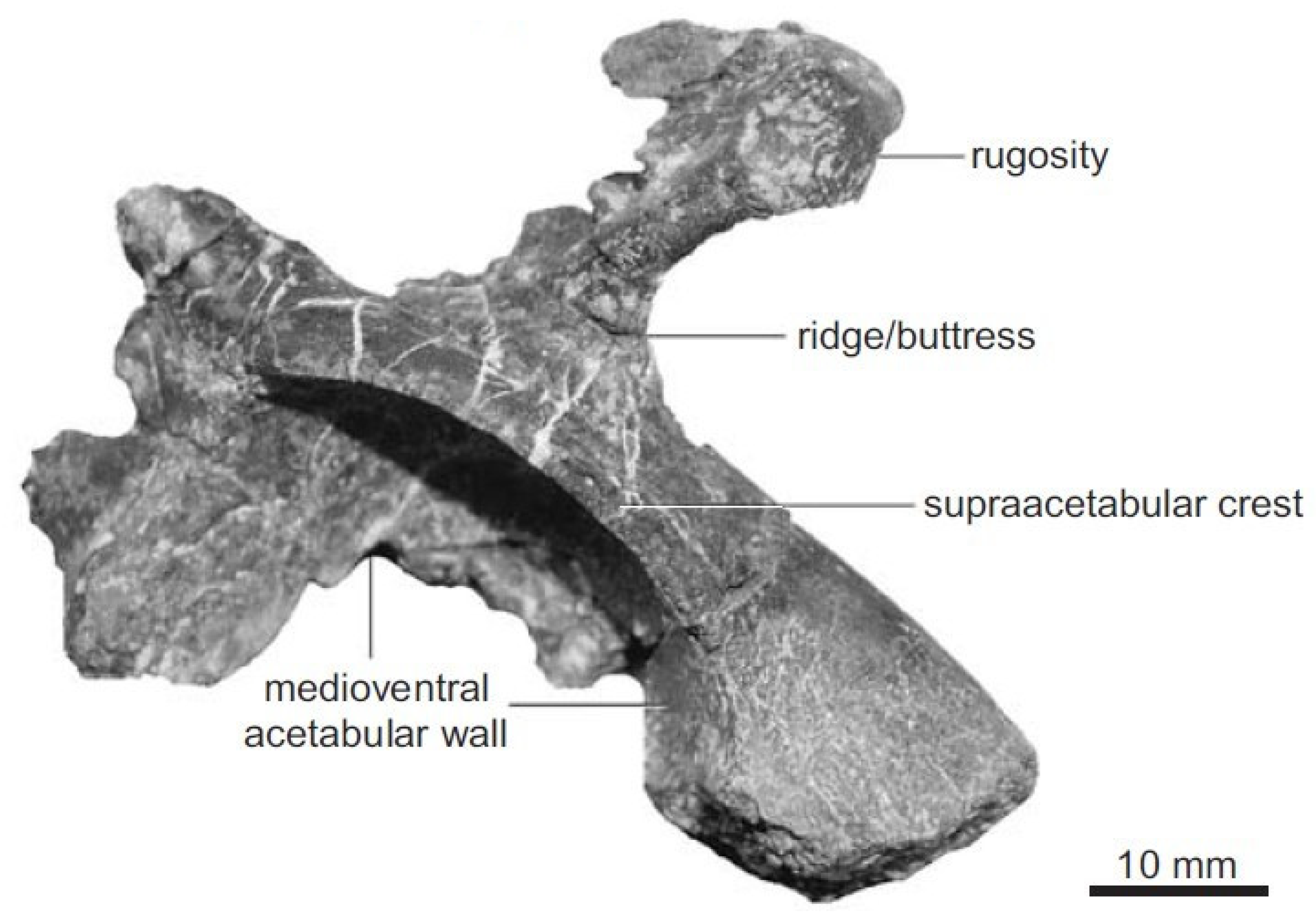

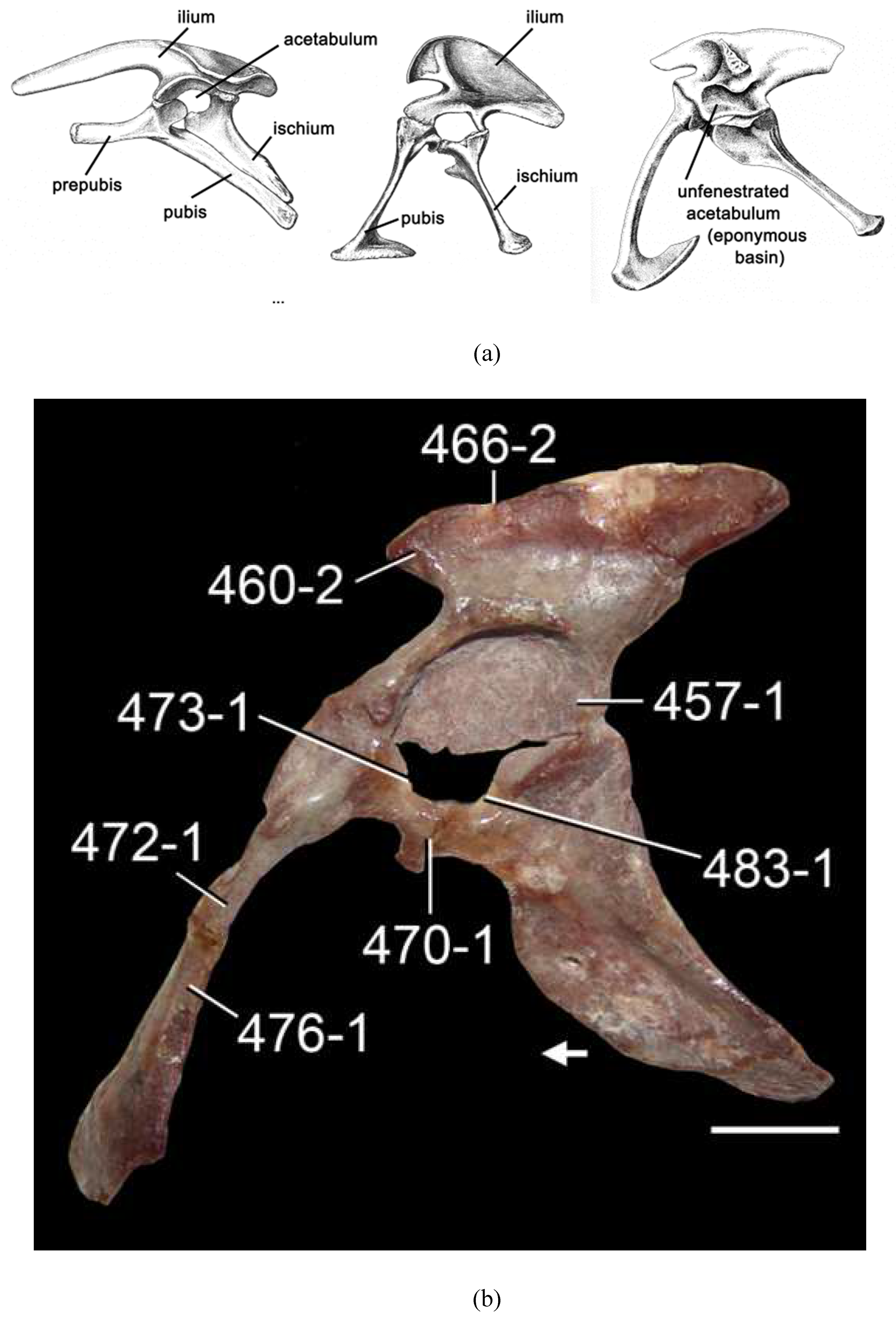

2. Hip joint morphology in basal Archosauria and Dinosauria

3. Hip joint morphology in extant birds (Neornithes)

4. The hip joint morphology of basal birds and pennaraptoran “maniraptorans”

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Huxley, T.H. On the animals which are most nearly intermediate between birds and reptiles. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History 1868, 2, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, J.H. Archaeopteryx and the origin of birds. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1976, 8, 91–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, J.H. The Question of the Origin of Birds. In Origins of the Higher Groups of Tetrapods: Controversy and Consensus; Schultze, H.-P., Trueb, L., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 467–484. ISBN 0-8014-2497-6. [Google Scholar]

- Padian, K. Macroevolution and the origin of major adaptations: vertebrate flight as a paradigm for the analysis of patterns. In Proceedings of the Third North American Paleontological Convention; Mamet, B.L., Copeland, M.J., Eds.; Business and Economic Service: Toronto, CA, 1982; Volume 2, pp. 485–489. [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier, J.A. Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. Mem. Calif. Acad. Sci. 1986, 8, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappe, L.M. Enantiornithine (Aves) tarsometatarsi and the avian affinities of the Late Cretaceous Avisauridae. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 1992, 12, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feduccia, A. The Origin and Evolution of Birds, 2nd ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-300-07861-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, G. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781119020769. [Google Scholar]

- De Queiroz, K.; Cantino, P.D.; Gauthier, J.A. (Eds.) Phylonyms: A Companion to the PhyloCode; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-138-33293-5. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, G.S. Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-8018-6763-0. [Google Scholar]

- Makovicky, P.J.; Zanno, L.E. Theropod Diversity and the Refinement of Avian Characteristics. In Living Dinosaurs: The Evolutionary History of Birds; Dyke, G., Kaiser, G., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 9–29. ISBN 978-0-470-65666-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gatesy, S.M. Caudofemoral musculature and the evolution of theropod locomotion. Paleobiology 1990, 16, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatesy, S.M. Functional evolution of the hind limb and tail from basal birds to theropods. In Functional Morphology in Vertebrate Paleontology; Thomason, J.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; pp. 219–234. ISBN 9780521629218. [Google Scholar]

- Gatesy, S.M. Locomotory Evolution on the Line to Modern Birds. In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 432–447. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- Carrano, M.T. Locomotion in non-avian dinosaurs: integrating data from hindlimb kinematics, in vivo strains, and bone morphology. Paleobiology 1998, 24, 450–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farlow, J.O.; Gatesy, S.M.; Holtz, Jr., T. R.; Hutchinson, J.R.; Robinson, J.M. Theropod locomotion. Amer. Zool. 2000, 40, 640–663. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, J.R.; Gatesy, S.M. Adductors, abductors, and the evolution of archosaur locomotion. Paleobiology 2000, 26, 734–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.R. The evolution of pelvic osteology and soft tissues on the line to extant birds (Neornithes). Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2001, 131, 123–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.R.; Allen, V. The evolutionary continuum of limb function from early theropods to birds. Naturwissenschaften 2009, 96, 423–448. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, C.T.; Botelho, J.F.; Hanson, M.; Fabbri, M.; Smith-Paredes, D.; Carney, R.M.; Norell, M.A.; Egawa, S.; Gatesy, S.M.; Rowe, T.B.; Elsey, R.M.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Bhullar, B.-A.S. The developing bird pelvis passes through ancestral dinosaur conditions. Nature 2022, 608, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnolin, F.L.; Ezcurra, M.D. The validity of Lagosuchus talampayensis Romer, 1971 (Archosauria, Dinosauriformes), from the Late Triassic of Argentina. Breviora 2019, 565, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charig, A.J. The evolution of the archosaur pelvis and hindlimb: an explanation in functional terms. In Studies in Vertebrate Evolution: Essays Presented to F. R. Parrington; Joysey, K.A., Kemp, T.S., Eds.; Oliver and Boyd: Edinburgh, UK, 1972; pp. 121–155. ISBN 9780050021311. [Google Scholar]

- Sereno, P.C.; Arcucci, A.B. Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Lagerpeton chanarensis. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 1994, 13, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, P.C.; Arcucci, A.B. Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, gen. nov. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 1994, 14, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingham-Soliar, T. Evolution of birds: ichthyosaur integumental fibers conform to dromaeosaur protofeathers. Naturwissenschaften 2003, 90, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingham-Soliar, T. The dinosaurian origin of feathers: perspectives from dolphin (Cetacea) collagen fibers. Naturwissenschaften 2003, 90, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feduccia, A.; Lingham-Soliar, T.; Hinchliffe, J.R. Do feathered dinosaurs exist? Testing the hypothesis on neontological and paleontological evidence. J. Morphol. 2005, 266, 125–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingham-Soliar, T.; Feduccia, A. , Wang, X. A new Chinese specimen indicates that “protofeathers” in the Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Sinosauropteryx are degraded collagen fibers. Proc. R. Soc. B 2007, 274, 1823–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feduccia, A. The Riddle of the Feathered Dragons: Hidden Birds of China; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-300-16435-0. [Google Scholar]

- Feduccia, A. Bird origins anew. Auk 2013, 130, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feduccia, A. Romancing the Birds and Dinosaurs: Forays in Postmodern Paleontology; BrownWalker: Irvine, CA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-59942-606-8. [Google Scholar]

- Foth, C. On the identification of feather structures in stem-line representatives of birds: evidence from fossils and actuopalaeontology. Paläontol. Z. 2012, 86, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rauhut, O.W.M; Foth, C.; Tischlinger, H.; Norell, M.A. Exceptionally preserved juvenile megalosauroid theropod dinosaur with filamentous integument from the Late Jurassic of Germany. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11746–11751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godefroit, P.; Sinitsa, S.M.; Dhouailly, D.; Bolotsky, Y.L.; Sizov, A.V.; McNamara, M.E.; Benton, M.J.; Spagna, P. A Jurassic ornithischian dinosaur from Siberia with both feathers and scales. Science 2014, 345, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroit, P.; Sinitsa, S.M.; Cincotta, A.; McNamara, M.E.; Reshetova, S.A.; Dhouailly, D. Integumentary Structures in Kulindadromeus zabaikalicus, a Basal Neornithischian Dinosaur from the Jurassic of Siberia. In The Evolution of Feathers: From Their Origin to the Present; Foth, C., Rauhut, O.W.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, CH, 2020; pp. 47–65. ISBN 978-3-030-27223-4. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. A.; Chiappe, L.M.; Clarke, J.A.; Edwards, S.V; Nesbitt, S.J.; Norell, M.A.; Stidham, T.A.; Turner, A.; van Tuinen, M.; Vinther, J.; Xu, X. Rhetoric vs. reality: A commentary on “Bird Origins Anew” by A. Feduccia. The Auk: Ornithological Advances 2015, 132, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Filamentous Integuments in Novavialan Theropods and Their Kin: Advances and Future perspectives for Understanding the Evolution of Feathers. In The Evolution of Feathers: From Their Origin to the Present; Foth, C., Rauhut, O.W.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, CH, 2020; pp. 67–78. ISBN 978-3-030-27223-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sansom, R.S.; Gabbott, S.E.; Purnell, M.A. Non-random decay of chordate characters causes bias in fossil interpretation. Nature 2010, 463, 797–800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sansom, R.S.; Gabbott, S.E.; Purnell, M.A. Decay of vertebrate characters in hagfish and lamprey (Cyclostomata) and the implications for the vertebrate fossil record. Proc. R. Soc. B 2011, 278, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, R.S.; Willis, M.A. Fossilization causes organisms to appear erroneously primitive by distorting evolutionary trees. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2458:1-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdock, D.J.E.; Gabbott, S.E.; Mayer, G.; Purnell, M.A. 2014. Decay of velvet worms (Onychophora), and bias in the fossil record of lobophodians. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014, 14, 222:1-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanglu, K.; Caron, J.-B.; Cameron, C.B. Using experimental decay of modern forms to reconstruct the early evolution and morphology of fossil enteropneusts. Paleobiology 2015, 41, 460–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sansom, R.S. Bias and sensitivity in the placement of fossil taa resulting from interpretations of missing data. Syst. Biol. 2015, 64, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, R.S.; Gabbott, S.E.; Purnell, M.A. Atlas of vertebrate decay: a visual and taphonomic guide to fossil interpretation. Palaeontology 2013, 56, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansom, R.S. Preservation and phylogeny of Cambrian ecdysozoans tested by experimental decay of Priapulus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32817:1-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, D.E.G.; McMahon, S. The role of experiments in investigating the taphonomy of exceptional preservation. Palaeontology 2016, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, R.J.; Smith, M.R. Phylogenetic signal and bias in paleontology. Syst. Biol. 2022, 71, 986–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, J.C.; Sansom, R.S. Multivariate mapping of ontogeny, taphonomy and phylogeny to reconstruct problematic fossil taxa. Proc. R. Soc. B 2023, 290, 20230333:1-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padian, K.; Chiappe, L.M. The origin and early evolution of birds. Biol. Rev. 1998, 73, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, F.C.; Pourtless, J.A., IV. Cladistics and the origin of birds: a review and two new analyses. Ornithol. Monogr. 2009, 66, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. The Rise of Birds: 225 Million Years of Evolution; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, US, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4214-1590-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, S.; Mortimer, M.; Wahl, W.R.; Lomax, D.R.; Lippincott, J.; Lovelace, D.M. A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight. PeerJ 2019, e7247, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lü, J.; Dong, Z.; Azuma, Y.; Barsbold, R.; Tomida, Y. Oviraptorosaurs compared to birds. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution; Zhou, Z., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, CN, 2002; pp. 175–189, ISBN 9787030105516. [Google Scholar]

- Maryańska, T.; Omsólska, H.; Wolsan, M. Avialan status for Oviraptorosauria. Acta Paleontol. Pol. 2002, 47, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Persons, W.S., IV; Currie, P.J. Dragon tails: convergent caudal morphology in winged archosaurs. Acta Geol. Sin-Engl. 2012, 86, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkin, B. Aerial ability in basal Deinonychosauria. Bull. Gunma Mus. Natu. Hist. 2014, 18, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, B. Scansorial and aeriability in Scansoriopterygidae and basal Oviraptorosauria. Hist. Biol. 2021, 31, 3202–3214. [Google Scholar]

- Hutson, J.D.; Hutson, K.N. An examination of forearm bone mobility in Alligator mississippiensis (Daudin, 1802) and Struthio camelus Linnaeus, 1758 reveals that Archaeopteryx and dromaeosaurs shared an adaptation for gliding and/or flapping. Geodiversitas 2015, 37, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, J.D.; Hutson, K.N. Retention of the flight-adapted avian finger-joint complex in the Ostrich helps identify when wings began evolving in dinosaurs. Ostrich 2018, 89, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurochkin, E.N. Parallel evolution of theropod dinosaurs and birds. Entomol. Rev. 2006, 86, S45-58. [Google Scholar]

- Dececchi, T.A.; Larsson, H.C.E.; Pittman, M.; Habib, M.B. High flyer or high fashion? A comparison of flight potential among small bodied paravians. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2020, 440, 295–320. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, R.; Pittman, M.; Goloboff, P.A.; et al. Potential for powered flight neared by most close avialan relatives, but few crossed its thresholds. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerkas, S.A.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Flying dromaeosaurs. In Feathered Dinsoaurs and the Origin of Flight; Czerkas, S.J., Ed.; Dinosaur Museum: Blanding, UT, USA, 2002; pp. 127–135. ISBN 1-932075-01-1. [Google Scholar]

- Feduccia, A. Birds are dinosaurs: Simple answer to a complex problem. Auk 2002, 119, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.D. A basal archosaurian origin for birds. Acta Zoolog. Sin. 2004, 50, 978–990. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.D. Origins of avian flight—a new perspective. Oryctos 2008, 7, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Feduccia, A.; Czerkas, S.A. Testing the neoflightless hypothesis: propatagium reveals flying ancestry of oviraptorosaurs. J. Ornithol. 2015, 156, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Pourtless, J.A., IV. Skepticism, the critical standpoint, and the origin of birds: a partial critique of Havstad and Smith (2019). Biol. Philos. 2022, 37, 57:1-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumel, J.J.; King, A.S.; Breazile, J.S.; Evans, H.E.; Vanden Berge, J.C. (Eds.) Handbook of Avian Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium, 2nd ed.; Nuttal Ornithological Club: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; ISBN 9781877973345. [Google Scholar]

- Cantino, P.D.; de Queiroz, K. International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature (PhyloCode) Version 6; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-138-332829. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, M.J.; Clark, J.M. Archosaur phylogeny and the relationships of the Crocodylia. In The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds; Benton, M.J., Ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1988; pp. 295–338. ISBN 9780198577058. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, M.J. Scleromochlus taylori and the origin of dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 1999, 354, 1423–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, S.J. The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2011, 352, 1–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcura, M.D. The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1778:1-385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, L.M. Cretaceous avian remains from Patagonia shed new light on the early radiation of birds. Alcheringa 1991, 15, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, L.M. The first 85 million years of avian evolution. Nature 1995, 378, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, L.M. Late Cretaceous birds of southern South America: anatomy and systematics of Enantiornithines and Patagopteryx deferrariisi. Münchner Geowiss. Abh. A 1996, 30, 203–244. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.D. The origin and early radiation of birds. In Perspectives in Ornithology; Brush, A.H., Clark, G.A., Jr., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 291–338. ISBN 978-0-521-24857-0. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.D. The beginning of the modern avian radiation. Travaux et Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de Lyon 1987, 99, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sereno, P.C.; Rao, C.; Li, J. Sinornis santensis (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Early Cretaceous of Northeastern China. In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 184–208. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- Padian, K.; Hutchinson, J.R.; Holtz, Jr., T. R. Phylogenetic definitions and nomenclature of the major taxonomic categories of the carnivorous Dinosauria (Theropoda). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 1999, 19, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.A.; Norell, M.A. The Morphology and Phylogenetic Position of Apsaravis ukhaana from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit. 2002, 3387, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.A. Morphology, phylogenetic taxonomy, and systematics of Ichythyornis and Apatornis (Avialae: Ornithurae). Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2004, 286, 1–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feduccia, A. Mesozoic aviary takes form. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou Hou, L.; Martin, L.D.; Zhou, Z.; Feduccia, A.; Zhang, F. A diapsid skull in a new species of the primitive bird Confuciusornis. Nature 1999, 399, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. Discovery of an ornithurine bird and its implications for Early Cretaceous avian radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18998–19002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. Mesozoic birds of China—a synoptic review. Front. Biol. China 2007, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, L.M. Basal Bird Phylogeny: Problems and Solutions. In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 448–472. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, A. The Osteology of the Reptiles; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1956; ISBN 9780226724911. [Google Scholar]

- Naples, V.L.; Martin, L.D.; Simmons, J. The pelvis in early birds and dinosaurs. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution; Zhou, Z., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Science Press: Beijing, CN, 2002; pp. 203–210, ISBN 9787030105516. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, M.G.; Williams, M.E. A re-evaluation of the enigmatic dinosauriform Caseosaurus crosbyensis from the Late Triassic of Texas, USA and its implications for early dinosaur evolution. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 2018, 63, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzik, J. A beaked herbivorous archosaur with dinosaur affinities from the early Late Triassic of Poland. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2003, 23, 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peecook, B.R.; Sidor, C.A.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Smith, R.M.H.; Steyer, J.S.; Angielczyk, K.D. A new silesaurid from the upper Ntawere Formation of Zambia (Middle Triassic) demonstrates the rapid diversification of Silesauridae (Avemetatarsalia, Dinosauriformes). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2013, 33, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martz, J.W.; Small, B.J. Non-dinosaurian dinosauromorphs from the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of the Eagle Basin, northern Colorado: Dromomeron romeri (Lagerpetidae) and a new taxon, Kwanasaurus williamparkeri (Silesauridae). PeerJ 2019, e7551:1-71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.C.; McPhee, B.W.; Marsola, J.C.dA.; Roberto-da-Silva, L.; Cabreira, S.F. Anatomy of the dinosaur Pampadromaeus barberenai (Saurischia—Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation of southern Brazil. PloS ONE 2019, 14, e0212543:1-64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereno, P.C.; Martínez, R.N.; Alcober, O.A. Osteology of Eoraptor lunensis (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2013, 32(s1), 83–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.C. Basal Saurischia. In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.; Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 25–46. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, C.; Müller, R.T.; Langer, M.; Pretto, F.A.; Kerber, L.; Dias da Silva, S. Gnathovorax cabreirai: a new early dinosaur and the origin and initial radiation of predatory dinosaurs. PeerJ 2019, e7963:1-23. [Google Scholar]

- Tykoski, R.S.; Rowe, T. Ceratosauria. In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.; Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 47–70. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, D.; Rauhut, O.W.M. A Middle Jurassic abelisaurid from Patagonia and the early diversification of theropod dinosaurs. Proc. Roy. Soc. B 2012, 279, 3170–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsola, J.C.A.; Bittencourt, J.S.; Butler, R.J.; Da Rosa, A.A.S.; Sayão, J.M.; Langer, M.C. A new dinosaur with theropod affinities from the Santa Maria Formation, south Brazil. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2018, 38, e1531878:1-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.H.; Makovicky, P.J.; Norell, M.A. A review of dromaeosaurid systematics and paravian phylogeny. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2012, 371, 1–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusatte, S.L.; Lloyd, G.T.; Wang, S.C.; Norell, M.A. Gradual assembly of avian body plan culminated in rapid rates of evolution across the dinosaur-bird transition. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 2386–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, F.; Campbell, Jr., K.E. The antitrochanter of birds: form and function in balance. Auk 2007, 124, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perle, A.; Chiappe, L.M.; Barsbold, R.; Clark, J.M.; Norell, M.A. Skeletal morphology of Mononykus olecranus (Theropoda: Avialae) from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit. 1994, 3105, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Novas, F.E. Anatomy of Patagonykus puertai (Theropoda, Avialae, Alvarezsauridae), from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 1997, 17, 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, L.M.; Norell, M.A.; Clark, J.M. The Cretaceous, Short-Armed Alvarezsauridae Mononykus and Its Kin. In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 87–120. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Park, J.-Y.; Lee, Y.-N.; Kim, S.-H.; Lü, J.; Barsbold, R.; Tsogtbaatar, K. A new alvarezsaurid dinosaur from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15494:1-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. M.; Maryańska, T.; Barsbold, R. Therizinosauroidea. In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.; Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 151–164. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zanno, L.E. Osteolgy of Falcarius utahensis (Dinosauria: Theropoda): characterizing the anatomy of basal therizinosaurs. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2010, 158, 196–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-C.; Zanno, L.E.; Wang, S.; Xu, X. Postcranial osteology of Beipiaosaurus inexpectus (Theropoda: Therizinosauria). PloS ONE 2021, 16, e0257913:1-28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzanov, S.M. New data on the pelvic structure of Avimimus. Paleont. Jour. 1983, 4, 115–116. [Google Scholar]

- Osmólska, H.; Currie, P.J.; Barsbold, R. Oviraptorosauria. In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.; Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 165–183. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4. [Google Scholar]

- Makovicky, P.J.; Norell, M.A. Troodontidae. In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.; Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 184–195. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4. [Google Scholar]

- Agnolin, F.L.; Novas, F.E. Unenlagiid theropods: are they members of the Dromaeosauridae (Theropoda, Maniraptora)? An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2011, 83, 117–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lü, J.; Brusatte, S.L. A large, short-armed, winged dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of China and its implications for feather evolution. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11775:1-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianechini, F.A.; Makovicky, P.J.; Apesteguía, S.; Cerda, I. Postcrainal skeletal anatomy of the holotype and referred specimens of Buitreraptor gonzalezorum Makovicky, Apesteguía and Agnolín 2005 (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae), from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4558:1-84. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, C.A.; O’Connor, P.M.; Chiappe, L.M.; Turner, A.H. The osteology of the Late Cretaceous paravian Rahonavis ostromi from Madagascar. Palaeontol. Electron. 2020, 23, a29:1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novas, F.E.; Agnolín, F.L.; Motta, M.J.; Egli, F.B. Osteology of Unenlagia comaheunsis (Theropoda, Paraves, Unenlagiidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. Anat. Rec. 2021, 304, 2741–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.H.; Pol, D.; Norell, M.A. Anatomy of Mahakala omnogovae (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae), Tögrögiin Shiree, Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit. 2011, 3722, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Guha, K.; Shalini, S.; Kumar, C. Gross anatomical studies on the os-coxae and synsacrum of Japanese quail (Coturnix coturnix japonica). Indian J. Vet. Anat. 2014, 26, 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- Egawa, S.; Saito, D.; Abe, G.; Koji, T. Morphogenetic mechanism of the acquisition of the dinosaur-type acetabulum. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180604:1-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.P.; Holliday, C.M. Articular soft tissue anatomy of the archosaur hip joint: structural homology and functional implications. J. Morphol. 2015, 276, 601–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.P.; Middleton, K.M.; Hutchinson, J.R.; Holliday, C.M. Hip joint articular soft tissues of non-dinosaurian Dinosauromorpha and early Dinosauria: evolutionary and biomechanical implications for Saurischia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2018, 38, e1427583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, M.J. Dinosaurs Rediscovered: How a Scientific Revolution is Rewriting History; Thames and Hudson: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9780500052006. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, C.M.; Ridgely, R.C.; Sedlmayr, J.C.; Witmer, L.M. Cartilaginous epiphyses in extant archosaurs and their implications for reconstructing limb function in dinosaurs. PloS ONE 2010, 5, e13120:1-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, B.-A.S.; Hanson, M.; Fabbri, M.; Pritchard, A.; Bever, G.S.; Hoffman, E. How to Make a Bird Skull: Major Transitions in the Evolution of the Avian Cranium, Paedomorphosis, and the Beak as a Surrogate Hand. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2016, 56, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botelho, J.F.; Smith-Paredes, D.; Soto-Acuña, S.; O’Connor, J.; Palma, V.; Vargas, A.O. Molecular development of fibular reduction in birds and its evolution from dinosaurs. Evolution 2016, 70, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Paredes, D.; Núñez-León, D.; Soto-Acuña, S.; O’Connor, J.; Botelho, J.F.; Vargas, A.O. Dinosaur ossification centres in embryonic birds uncover developmental evolution of the skull. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1966–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoupling the skull and skeleton in a Cretaceous bird with unique appendicular morphologies. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 20–31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Holm, R.W.; Parnell, D. The Process of Evolution; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1963; ISBN 0070191336. [Google Scholar]

- Yuri, T.; Kimball, R.T.; Harshman, J.; et al. Parsimony and model-based analyses of indels in avian nuclear genes reveal congruent and incongruent phylogenetic signals. Biology 2013, 2, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A new Mesembriornithinae (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) provides new insights in the phylogeny and sensory capabilities of terror birds. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2015, 35, e912656:1-18. [CrossRef]

- A Well-Preserved Partial Skeleton of the Poorly Known Early Miocene Serieam Noriegavis santacruensis. Acta Paleontol. Pol. 2013, 60, 589–598. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.; Chiappe, L.M.; Bell, A. Pre-modern Birds: Avian Divergences in the Mesozoic. In Living Dinosaurs: The Evolutionary History of Birds; Dyke, G., Kaiser, G., Eds. Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 39–114. ISBN 978-0-470-65666-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z. A new basal bird from China with implications for morphological diversity in early birds. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19700:1-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A new clade of basal Early Cretaceous pygostylian birds and developmental plasticity of the avian shoulder girdle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10708–10713. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, T.; Azuma, Y.; Kawabe, S.; Shibata, M.; Miyata, K.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Z. An unusual bird (Theropoda, Avialae) from the Early Cretaceous of Japan suggests complex evolutionary history of basal birds. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 399:1-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnolin, F.L.; Motta, M.J.; Egli, F.B.; Lo Coco, G.; Novas, F.E. Paravian Phylogeny and the Dinosaur-Bird Transition: An Overview. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 6, 252:1-28. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman, M.; O’Connor, J.; Field, D.J.; Turner, A.H. , Ma, W.; Makovicky, P.J.; Xu, X. Pennaraptoran Systematics. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2020, 440, 7–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, R.; Li, Q.; Meng, Q.; Norell, M.A.; Gao, K.-Q. New specimens of Anchiornis huxleyi (Theropoda: Paraves) from the Late Jurassic of northeastern China. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2017, 411, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.A.; Sampson, S.D.; Chiappe, L.M.; Krause, D.W. The theropod ancestry of birds: new evidence from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Science 1998, 279, 1915–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Xu, X. Pennaraptoran Theropod Dinosaurs Past Progress and New Frontiers. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2020, 440, 1–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiki, Z.; Vremir, M.; Brusatte, S.L.; Norell, M.A. An aberrant island-dwelling theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Romania. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15357–15361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusatte, S.L.; Vremir, M.; Csiki-Sava, Z.; Turner, A.H.; Watanabe, A.; Erickson, G.M.; Norell, M.A. The osteology of Balaur bondoc, an island-dwelling dromaeosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of Romania. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2013, 374, 1–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroit, P.; Cau, A.; Dong-Yu, H.; Escuillié, F.; Wenhao, W.; Dyke, G. A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds. Nature 2013, 498, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foth, C.; Tischlinger, H.; Rauhut, O.W.M. New specimen of Archaeopteryx provides insights into the evolution of pennaceous feathers. Nature 2014, 511, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cau, A.; Brougham, T.; Naish, D. The phylogenetic affinities of the Late Cretaceous Romanian theropod Balaur bondoc (Dinosauria, Maniraptoran): dromaeosaurid or flightless bird? PeerJ 2015, e1032:1-36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Chiappe, L.M.; Meng, Q.; O’Connor, J.K.; Wang, X.; Cheng, X.; Liu, J. A new basal lineage of Early Cretaceous birds from China and its implications on the evolution of the avian tail. Palaeontology 2008, 51, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.K.; Sullivan, C. Reinterpretation of the Early Cretaceous maniraptoran (Dinosauria, Theropoda) Zhongornis haoae as a scansoriopterygid-like non-avian, and morphological resemblances between Scansoriopterygids and basal oviraptorosaurs. Vert. PalAs. 2014, 52, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F.; Li, Z. A new Lower Cretaceous bird from China and tooth reduction in early avian evolution. Proc. Roy. Soc. B 2010, 277, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, J.K.; Zhou, Z. A redescription of Chaoyangia beishanensis (Aves) and a comprehensive phylogeny of Mesozoic birds. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2013, 11, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerkas, S.A.; Yuan, C. An arboreal maniraptoran from Northeast China. In Feathered Dinsoaurs and the Origin of Flight; Czerkas, S.J., Ed.; Dinosaur Museum: Blanding, UT, USA, 2002; pp. 63–95. ISBN 1-932075-01-1. [Google Scholar]

- Czerkas, S.A.; Feduccia, A. Jurassic archosaur is a non-dinosaurian bird. J. Ornithol. 2014, 155, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.D. Mesozoic Birds and the Origin of Birds. In Origins of the Higher Groups of Tetrapods: Controversy and Consensus; Schultze, H.-P., Trueb, L., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 485–540. ISBN 0-8014-2497-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wellnhofer, P. Archaeoptery: The Icon of Evolution; Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: München, DE, 2009; ISBN 978-3-89937-108-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, D.; Kundrát, M.; Tischlinger, H.; Dyke, G.; Carney, R.M. Ultraviolet light illuminates the avian nature of the Berlin Archaeopteryx skeleton. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6518:1-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, G.; Pohl, B.; Hartman, S.; Peters, D.S. The teneth skeletal specimen of Archaeopteryx. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2007, 149, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, D. Archaeopteryx—a re-evaluation suggesting an arboreal habitat and an intermediate stage in the trees down origin of flight. N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh. 2007, 245, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellnhofer, P. Das fünfte Skelettexemplar von Archaeopteryx. The fifth skeletal example of Archaeopteryx. Palaeontogr. A 1974, 147, 169–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kundrát, M.; Nudds, J.; Kear, B.P.; Lü, J.; Ahlberg, P. The first specimen of Archaeopteryx from the Upper Jurasic Mörnsheim Formation of Germany. Hist. Biol. 2019, 31, 3–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnolin, F.; Novas, F.E. Avian Ancestors: A Review of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Theropods Unenlagiidae, Microraptoria, Anchiornis, and Scansoriopterygidae; Springer: Dordrecht, NL, 2013; ISBN 978-94-007-5636-6. [Google Scholar]

- Elzanowski, A. A new genus and species for the largest specimen of Archaeopteryx. Acta Paleontol. Pol. 2001, 46, 519–532. [Google Scholar]

- Elzanowski, A. Archaeopterygidae (Upper Jurassic of Germany). In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 129–159. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Norell, M.; Sullivan, C.; Hone, D.; Erickson, G.; Wang, X.; Han, F.; Yu, G. A new feathered maniraptoran dinosaur fossil that fills a morphological gap in avian origin. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2009, 54, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; You, H.; Han, F. An Archaeopteryx-like theropod from China and the origin of Avialae. Nature 2011, 475, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. Anatomy of the primitive bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2003, 40, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, L.; Hou, L.; Xu, X. A New Sapeornithid Bird from China and Its Implications for Early Avian Evolution. Acta Geol. Sin-Engl. 2010, 84, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, L.M.; Ji, S.; Ji, Q.; Norell, M.A. Anatomy and systematics of the Confuciusornithidae (Theropoda: Aves) from the Late Mesozoic of northeastern China. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1999, 242, 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L.D.; Zhou, Z.; Hou, L.; Feduccia, A. Confuciusornis sanctus compared to Archaeopteryx lithographica. Naturwissenschaften 1998, 85, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Hou, L. The Discovery and Study of Mesozoic Birds in China. In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 160–183. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F. A long-tailed, seed-eating bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Nature 2002, 418, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.K.; Sun, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z. A new species of Jeholornis with complete caudal integument. Hist. Biol. 2012, 24, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, L.M.; Walker, C.A. Skeletal Morphology and Systematics of the Cretaceous Euenantiornithes (Ornithothoraces: Enantiornithes). In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 240–267. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappe, L.M. Osteology of the Flightless Patagopteryx deferrariisi from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina). In Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs; Chiappe, L.M., Witmer, L.M., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 281–316. ISBN 0-520-20094-2. [Google Scholar]

- You, H.-L.; Lamanna, M.C.; Harris, J.D.; et al. A Nearly Modern Amphibious Bird from the Early Cretaceous of Northwestern China. Science 2006, 312, 1640–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zheng, X.; O’Connor, J.K.; Lloyd, G.T.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z. The oldest record of ornithuromorpha from the early cretaceous of China. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6987:1-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.K.; Zelenkov, N.V. The Phylogenetic Position of Ambiortus: Comparison with Other Mesozoic Birds from Asia. Paleontol. J. 2013, 47, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.D.; Tate, Jr., J. The Skeleton of Baptornis advenus (Aves: Hesperornithiformes). Smithson. Contrib. Paleobiol. 1976, 27, 35–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.-N.; Currie, P.J.; Sissons, R.; Park, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Barsbold, R.; Tsogtbaatar, K. A non-avian dinosaur with a streamlined body exhibits potential adaptations for swimming. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1185:1-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, O.C. Odontornithes, a Monograph of the Extinct Toothed Birds of North America. Report of the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel 1880, 7, 1–201. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, J.; Chen, A.; Wilson, L.E.; Bhullar, B.-A.S.; Burnham, D.; Field, D.J. Forty new specimens of Ichthyornis provide unprecedented insight into the postcranial morphology of crownward stem group birds. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13919:1-134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-H.; Wang, X.-L.; Zhang, F.-C.; Xu, X. Important features of Caudipteryx—evidence from two nearly complete new specimens. Vert. PalAs. 2000, 38, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.-H.; Wang, X.-L. 2000. A new species of Caudipteryx from the Yixian Formation of Liaoning, northeast China. Vert. PalAs. 2000, 38, 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y. A new caudipterid from the Lower Cretaceous of China with information on the evolution of the manus of Oviraptorosauria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6431:1-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, P.J.; Russell, D.A. Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River (Oldman) Formation of Alberta, Canada. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1988, 25, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. The Type Specimen of Oviraptor philoceratops, a Theropod Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh. 1992, 186, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanoff, A.M.; Norell, M.A. Osteology of Khaan meckennai (Oviraptorosauria: Theropoda). Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2012, 372, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funston, G.F.; Tsogtbaatar, C.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Sullivan, C.; Currie, P.J. A new twi-fingered dinosaur sheds light on the radiation of Oviraptorosauria. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 201184:1-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, M.W.; Funston, G.F.; Currie, P.J. New material reveals the pelvic morphology of Caenagnathidae (Theropoda, Oviraptorosauria). Cretac. Res. 2020, 114, 104521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funston, G.F.; Mendonca, S.E.; Currie, P.J.; Barsbold, R. Oviraptorosaur anatomy, diversity and ecology in the Nemegt Basin. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018, 494, 101–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norell, M.A.; Clark, J.M.; Chiappe, L.M. An Embryonic Oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit. 2001, 3315, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weishampel, D.B.; Fastovsky, D.E.; Watabe, M.; Varricchio, D.; Jackson, F.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Barsbold, R. New oviraptorid embryos from Bugin-Tsav, Nemegt Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Mongolia, with insights into their habitat and growth. J. Vertebr. Paleonol. 2008, 28, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, J.; Currie, P.J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, H.; Jia, S. Chicken-sized oviraptorid dinosaurs from central China and their ontogenetic implications. Naturwissenschaften 2013, 100, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Currie, P.; Pittman, M.; Xing, L.; Meng, Q.; Lü, J.; Hu, D.; Yu, C. Mosaic evolution in an asymmetrically feathered troodontid dinosaur with transitional features. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14972:1-12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Ji, S.; Lü, J.; You, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. First avialian bird from China. Geol. Bull. China 2005, 24, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.; Lü, J.; Liu, S.; Kundrát, M.; Brusatte, S.L.; Gao, H. A New Troodontid from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province, China. Acta Geol. Sin-Engl. 2017, 91, 763–780. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuihiji, T.; Barsbold, R.; Watabe, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Tsogtbaatar, C.; Fujiyama, Y.; Suzuki, S. An exquisitely preserved troodontid theropod with new information on the palatal structure from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Naturwissenschaften 2014, 101, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Norell, M.A.; Wang, X.-L.; Makovicky, P.J.; Wu, X.-C. A basal troodontid from the Early Cretaceous of China. Nature 2002, 415, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, E.-P.; Martin, L.D.; Burnham, D.A.; Falk, A.R.; Hou, L.-H. A new species of Microraptor from the Jehol Biota of northeastern China. Palaeoworld 2012, 21, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Norell, M. .A.; Ji, Q.; Gao, K. New Specimens of Microraptor zhaoianus (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from Northeastern China. Am. Mus. Novit. 2002, 3381, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longrich, N.R.; Currie, P.J. A microraptorine (Dinosauria—Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5002–5007. [Google Scholar]

- Brusatte, S.L. A Mesozoic aviary. Science 2017, 335, 792–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novas, F.E.; Puerta, P.F. New evidence concerning avian origins from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. Nature 1997, 387, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novas, F.E. Avian Traits in the Ilium of Unenlagia comahuensis (Maniraptora, Avialae). In Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds; Currie, P.J., Koppelhus, E.B., Shugar, M.A., Wright, J.L., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2004; pp. 150–166. ISBN 0-253-34373-9. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, D. New Information on Bambiraptor feinbergi (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Montana. In Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds; Currie, P.J., Koppelhus, E.B., Shugar, M.A., Wright, J.L., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2004; pp. 67–111. ISBN 0-253-34373-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, J.H. Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana. Bull. Peabody Mus. Nat. Hist. 1969, 30, 1–165. [Google Scholar]

- Norell, M.A.; Makovicky, P.J. Important Features of the Dromaeosaurid Skeleton: Information from a New Specimen. Am. Mus. Novit. 1997, 3215, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Norell, M.A.; Makovicky, P.J. Important Features of the Dromaeosaurid Skeleton II: Information from Newly Collected Specimens of Velociraptor mongoliensis. Am. Mus. Novit. 1999, 3282, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt, S. The anatomy of Effigia okeeffeae (Archosauria, Suchia), theropod-like convergence, and the distribution of related taxa. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2007, 302, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, K.T.; Schachner, E.R. Disparity and convergence in bipedal archosaur locomotion. J. R. Soc. Interface 2012, 9, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, J.A.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Schachner, E.R.; Bever, G.S.; Joyce, W.G. The Bipedal Stem Crocodilian Poposaurus gracilis: Inferring Function in Fossils and Innovation in Archosaur Locomotion. Bull. Peabody Mus. Nat. Hist. 2011, 52, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farlow, J.O.; Schachner, E.R.; Sarrazin, J.C.; Klein, H.; Currie, P.J. Pedal Proportions of Poposaurus: Convergence and Divergence in the Feet of Archosaurs. Anat. Rec. 2014, 297, 1022–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachner, E.R.; Irmis, R.B.; Huttenlocker, A.K.; Sanders, K.; Cieri, R.L.; Nesbitt, S.J. Osteology of the Late Triassic Bipedal Archosaur Poposaurus gracilis (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from Western North America. Anat. Rec. 2020, 303, 874–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbaum, J.C. Postcranial skeleton of Postosuchus kirkpatricki (Archosauria: Paracrocodylomorpha), from the Upper Triassic of the United States. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2013, 379, 525–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickaryous, M.K.; Maryańska, T.; Weishampel, D.B. Ankylosauria. In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.; Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 363–392. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, P.; Forster, C.A.; Sampson, S.D. Ceratopsidae. In The Dinosauria, 2nd ed.; Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Osmólska, H., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 494–513. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.; Miyashita, T.; Wang, D.; Niu, K.; Currie, P.J. A new compsognathid theropod dinosaur from the oldest assemblage of the Jehold Biota in the Lower Cretaceous Huajiying Formation, northeastern China. Cretac. Res. 2020, 107, 104285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, J. The Osteology of Compsognathus longipes Wagner. Zitteliana 1978, 4, 73–118. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, P.J.; Chen, P.-J. Anatomy of Sinosauropteryx prima from Liaoning, northeastern China. Can. J. Earth Sci. 2001, 38, 1705–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Templin, R.J. Feathered Coelurosaurs from China: New Light on the Arboreal Origin of Avian Flight. In Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds; Currie, P.J., Koppelhus, E.B., Shugar, M.A., Wright, J.L., Eds.; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2004; pp. 251–281. ISBN 0-253-34373-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Templin, R.J. Palaeoecology, Aerodynamics, and the Origin of Avian Flight. In Earth and Life: Global Biodiversity, Extinction Intervals and Biogeographic Perturbations Through Time; J.A., Ed. Springer: Dordrecht, NL, 2012; pp. 585–612. ISBN 978-94-024-0491-3. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.; Persons, W.S., IV; Bell, P.R.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Miyashita, T.; Wang, F.; Currie, P.J. Piscivory in the feathered dinosaur Microraptor. Evolution 2013, 67, 2441–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.S.; Lim, J.D.; Lockley, M.G.; Xing, L.; Kim, D.H.; Piñuela, L.; Romilio, A.; Yoo, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Ahn, J. Smallest known raptor tracks suggest microraptorine activity in lakeshore setting. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16908:1-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Wang, Y.; McDonald, P.G.; et al. Earliest evidence for fruit consumption and potential seed dispersal by birds. eLife 2022, 11, e74751:1-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ge, Y.; Hu, H.; Stidham, T.A.; Li, Z.; Bailleul, A.M.; Zhou, Z. Intra-gastric phytoliths provide evidence for folivory in basal avialans of the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4558:1-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnham, D.A.; Feduccia, A.; Martin, L.D.; Falk, A.R. Tree climbing—a fundamental avian adaptation. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2011, 9, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Padian, K. Evolutionary insights from an ancient bird. Nature 2018, 557, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dial, K.P. Wing-Assisted Incline Running and the Evolution of Flight. Science 2003, 299, 402–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.N.; Panyutina, A.A. Where was WAIR in avian flight evolution? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2022, 137, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg, U.M. Vertebrate Flight: Mechanics, Physiology, Morphology, Ecology and Evolution; Springer: Berlin, DE, 1990; ISBN 978-3-642-83850-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kambic, R.E.; Roberts, T.J.; Gatesy, S.M. Long-axi rotation: a missing degree of freedom in avian bipedal locomotion. J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 217, 2770–2782. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, F.; Du, X. Four-winged dinosaurs from China. Nature 2003, 421, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, D.; Goloboff, P.A. The Impact of Unstable Taxa in Coelurosaurian Phylogeny and Resampling Support Measures for Parsimony Analyses. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2020, 440, 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- James, F.C. How many dinosaurs are birds? BioScience 2021, 71, 991–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalden, D.W. Forelimb Function in Archaeopteryx. In The Beginnings of Birds: Proceedings of the International Archaeopteryx Conference Eichstätt 1984; Hecht, M.K., Ostrom, J.H., Viohl, G., Wellnhofer, P., Eds.; Freunde des Jura-Museums Eichstätt: Willibaldsburg, DE, 1985; pp. 91–97. ISBN 3-9801178-0-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.-A.; O’connor, J.K.; Li, D.Q.; You, H.-L. New information on postcranial skeleton of the Early Cretaceous Gansus yumenensis (Aves: Ornithuromorpha). Hist. Biol. 2016, 28, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.A.; Atterholt, J.; O’Connor, J.K.; Lamanna, M.C.; Harris, J.D.; Li, D.-Q.; You, H.-L.; Dodson, P. A new, three-dimensionally preserved enantiornithine bird (Aves: Ornithothoraces) from Gansu Province, north-western China. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2011, 162, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Z. Insight into the growth pattern and bone fusion of basal birds from an Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11470–11475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).