1. Introduction

In recent decades, the technological revolution has brought about a significant change in work, speeding up its pace and increasing information overload. The characteristics of the contemporary labor market (e.g., temporary contracts, new psychological contracts between workers and employers, and perceptions of employability) jeopardize job security, representing an inexhaustible source of occupational stress and, in chronic cases, burnout.

Another major problem facing organizations today is the high turnover of employees, especially if they are highly specialized, which can represent high costs for the organization (Reiche, 2008). From the perspective of Avey et al. (2009), among other factors, one of the antecedents of turnover intentions is occupational stress. To Salama et al. (2022), occupational stress has a positive effect on turnover intentions, and this relationship is moderated by burnout.

Wang et al. (2019) studied the relationship between motivation and turnover intentions and found a significant and negative relationship between these two constructs.

The first objective of this study is to investigate whether burnout explains the relationship between work stress and turnover intentions an organization. Another objective is to study whether motivation moderates the relationship between job stress and turnover intentions.

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Job Stress and Turnover Intentions

Occupational stress can be defined as a reaction to the perception of a lack of resources to deal with a given situation (Jiang et al., 2022). Occupational stress, as an emotional state, is one of the stress issues affecting the working population and has gained enormous importance, being one of the most significant mental health problems (Bicho and Pereira, 2007). This results from a group of situations and experiences at work, i.e. "the interaction between working conditions and the characteristics of the worker, in such a way that the demands placed on them exceed their ability to cope with them" (Bicho and Pereira, 2007).

Turnover intentions are understood as the desire that employees have to leave the organization they are in and start looking for a new place of work (Benson, 2006). It is known that turnover intentions are the best predictor of voluntary departure from the organization (Long et al., 2012; Moreira et al., 2022; Park and Shaw, 2013), which can cause great damage to the organization, especially if the departing employee is highly qualified (Reiche, 2008).

In a study carried out by Jiang et al. (2022) with emergency medical professionals, the authors concluded that there is a positive and significant effect of occupational stress on turnover intentions. The results of the study by Tziner et al. (2015) go in the same direction, a positive and significant relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions.

This leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Occupational stress (users, management, colleagues, overwork, pay, family problems, working conditions) has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions.

2.2. Occupational Stress and Burnout

According to Maslach and Leiter (2016), burnout is a psychological syndrome characterized by high levels of emotional exhaustion (such as lethargy, exhaustion, and fatigue), depersonalization (such as negative attitudes, irritability, and social withdrawal), and reduced personal fulfilment (such as decreased productivity and/or inability to cope with the situation(s).

According to Meier’s (1984) theoretical framework, burnout is viewed as a state that follows a pattern of continuous work experiences in which the subject has low expectations for the presence of rewarding stimuli, high expectations for the presence of punishment, and low expectations for their capacity to manage their efforts. With such high expectations, it’s common to feel unhappy at work. According to this theoretical section, the environment and the subject interact to cause burnout rather than being caused only by it. According to Leiter (1988), people who experience emotional tiredness respond by depersonalizing, which causes them to break the psychological commitment they uphold at work, present a poor self-assessment in terms of personal fulfilment, and result in burnout. High levels of stress relate to emotional weariness.

Burnout can be considered a psychological syndrome that occurs when employees face a stressful work environment over a long time and perceive that their resources to cope with the demands of the job are scarce (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008; Maslach et al., 2001; Leiter and Maslach, 2016). It is therefore, considered to be a serious reaction to occupational stress, with physical and psychological changes (Marques-Pinto et al., 2003). The consequences of burnout are varied in terms of health, safety, and well-being, as well as productivity, quality of service and cost-effectiveness for the organization (Poghosyan et al., 2010; Carod-Artal and Vázquez-Cabrera, 2013). In a study carried out by Jesus et al. (2023) with healthcare professionals, it was found that burnout has a significant effect on suicidal behavior.

The following hypothesis is therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 2: Occupational stress (users, management, colleagues, overwork, remuneration, family problems, working conditions) has a significant and positive effect on burnout levels (disengagement, exhaustion).

2.3. Burnout and Turnover Intentions

As organizations are aware that high employee turnover, especially if they are highly specialized, represents high costs for them (Reiche, 2008), in recent years, there has been an increase in studies on the effect of burnout on increasing absenteeism rates and turnover intentions. According to Olivares-Faúndez et al. (2014), burnout is positively and significantly associated with absenteeism attitudes and behaviors. In turn, in a study of employees in the restaurant sector, Han et al. (2016) concluded that burnout caused by customer incivility has a positive and significant association with turnover intentions. For Rahim and Cosby (2016), as well as Kartono and Hilmiana (2018), there is also a direct relationship between burnout levels and turnover intentions.

These results from previous studies lead us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Burnout (disengagement, exhaustion) has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions.

2.4. Occupational Stress, Burnout and Turnover Intentions

As previously mentioned, occupational stress has a significant and positive association with burnout, which in turn has a positive and significant association with turnover intentions. Several studies report that burnout has a mediating effect on the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions (Han et al., 2016; Salama et al., 2022).

We aim to test whether burnout is the mechanism that explains the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions. To this end, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Burnout (disengagement, exhaustion) has a mediating effect on the relationship between occupational stress (users, management, colleagues, overwork, pay, family problems, working conditions) and turnover intentions.

2.5. Motivation at work and turnover intentions

Studies on motivation in the workplace have been the subject of great interest internationally due to the link between individual and organizational performance (Tamayo and Paschoal, 2003). Maslow (2000), a pioneer of theories on motivation, highlights the importance of this issue, stating that "The healthier we are emotionally, the more important our needs for creative fulfilment at work become. At the same time, the less we tolerate the violation of our needs for such fulfilment."

To better understand the concept of motivation, various researchers have proposed theories on motivation to understand its origin and influence on human behavior (Silva and Gomes, 2009). Gagné et al., (2015) contextualize and explain the "Self-Determination Theory", which is linked to theories of motivation. Thus, the authors present a multidimensional view of motivation based on three points: amotivation, which is contrary to motivation, i.e. it is the absence of motivation for a particular task; intrinsic motivation, characterized as a pleasant and interesting feeling, linked to intrinsic motivation, we have identified motivation, referring to performing a task because one identifies with it and it has a value and/or meaning (Grohmann et al., 2013); extrinsic motivation, characterized as a feeling that comes from the environment in order to avoid criticism and promote the self-esteem of others (Gagné et al., 2015). Inherent in extrinsic motivation is a sub-concept called "introjective", which refers to regulating behavior based on self-esteem contingencies (Grohmann et al., 2013).

Several studies claim that motivation has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions. In a study of professionals in the education sector, Hussain et al. (2018) concluded that motivation has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions and a positive effect on performance. In a more complex study, Zheng et al. (2021) found a negative and significant association between intrinsic motivation and turnover intentions. The following hypothesis was therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 5: Motivation (intrinsic, identified, introjected and extrinsic) has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions.

2.6. The moderating effect of motivation

As seen above, motivation has a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions. Furthermore, in a study carried out by Özbağ et al. (2014), they concluded that motivation moderates the relationship between burnout and turnover intentions. However, one of the aims of this study is to see if motivation has a moderating effect on the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions. The following hypothesis was therefore formulated:

Hypothesis 6: Motivation (intrinsic, identified, introjected and extrinsic) moderates the relationship between occupational stress (users, management, colleagues, overwork, pay, family problems, working conditions) and turnover intentions, with the relationship expected to be weaker for employees with high levels of motivation than for employees with low levels of motivation.

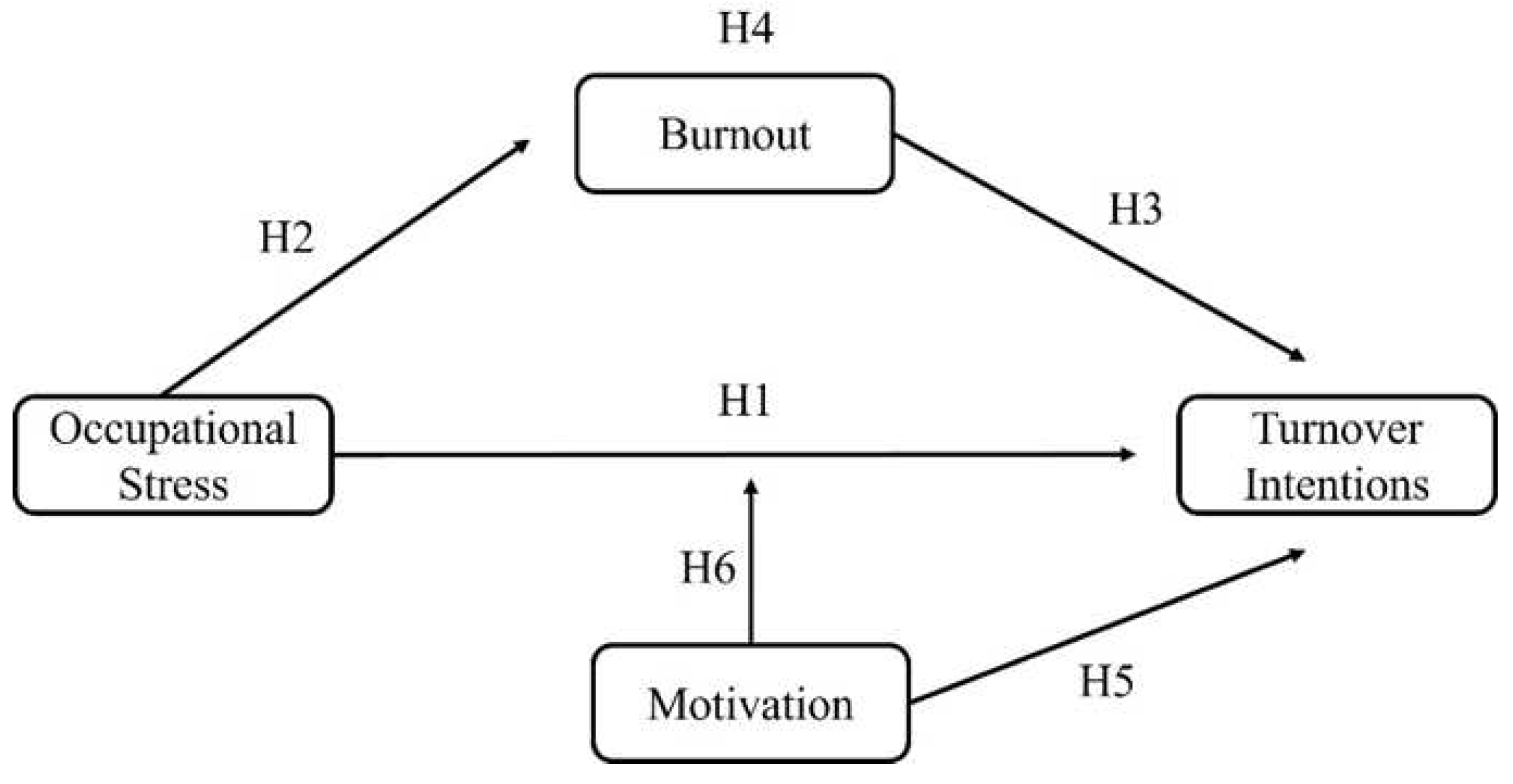

To integrate the hypotheses formulated in this study, a theoretical model was developed, which synthesized all the relationships (

Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data collection procedure

A total of 603 subjects voluntarily participated in this study, all employees of the Portuguese Tax and Customs Authority, which is part of the Ministry of Finance and belongs to the Direct State Administration. The data collection process was non-probabilistic, intentional and snowball (Trochim, 2000).

The questionnaire was posted online on the Google Forms platform, and its link was sent to employees of the Portuguese Customs Authority via the Trade Union Association of Tax and Customs Inspection Professionals (APIT). The questionnaire contained all the information about the purpose of the study, as well as guaranteeing the confidentiality of the answers given. Participants were also informed that their answers would never be known since the data would be processed considering all the answers given. At the beginning of the questionnaire, after reading the informed consent form, participants were asked if they agreed to answer the questionnaire. If participants chose the "no" option, they were directed to the end of the questionnaire, i.e., to the acknowledgements page.

The questionnaire included ten sociodemographic questions (age, gender, academic qualifications, length of service in the tax and customs authority, length of service in the civil service, district of residence, service to which they belonged, type of employment, staff group in the tax administration, method of admission and whether they were unionized) and four scales (occupational stress, burnout, motivation, and turnover intentions). Data was collected between April and June 2023.

3.2. Participants

The study sample consisted of 603 participants aged between 32 and 69 (M = 52.46; SD = 6.86), 320 (53.1%) female and 283 (46.9%) males. In terms of educational qualifications, 155 (25.7%) had a 12th-grade degree or less, 396 (65.7%) had a bachelor’s degree and 52 (8.6%) had a master’s degree or higher. Seniority in the customs authority varies between 1 and 46 years (M = 23.49; SD = 10.66), and seniority in the civil service varies between 5 and 47 years (M = 27.09; SD = 8.29). Concerning the district in which they live, the highest percentage of participants work in the district of Lisbon or Porto, although employees were working in all of Portugal’s districts (

Table 1).

Among these participants, 71 (11.8%) work in central services, 212 (35.2%) in finance directorates, 70 (11.6) in customs, 233 (38.6%) in finance services and 17 (2.8%) in customs offices. As for the method of employment, 264 (43.8%) were appointed, 16 (2.7%) were on service commission, and 323 (53.6%) were on public service contracts. Among these participants, 14 (2.3%) are managers, 67 (11.1%) are in tax and customs management, 262 (43.4%) are in tax and customs inspection/management, 133 (22.1%) belong to subsistence careers, 88 (14.6%) belong to IT staff and 39 (6.5%) to general regime staff. As for how they were hired, 536 (88.9%) were hired through a competitive procedure, 38 (6.3%) through internal mobility, 2 (0.3%) returned from unpaid leave, 12 (2%) are on service commission and 15 (205%) are in another situation. Regarding whether they were union members, 487 (80.8%) said they were union members, and 116 (19.2%) said they were not union members.

3.3. Data analysis procedure

The data was imported into SPSS Statistics 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA). The first step was to test the metric qualities of the instruments used in this study. To test the validity of the instruments measuring occupational stress, motivation and burnout, confirmatory factor analyses were carried out using AMOS Graphics 29 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA). The procedure followed a "model generation" logic (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1993). Six fit indices were merged following the published recommendations (Hu & Bentler, 1999), considering in the analysis of their adjustment the results obtained for the chi-square (χ²/df) ≤ 5; for the Tucker Lewis index (TLI) > 0. 90; for the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) > 0.90; for the comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90; for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08; for the Root Mean Square Residual (RMSR), a smaller value corresponds to a better adjustment. We then tested the construct reliability for each scale’s dimensions, which should be greater than 0.70. Finally, convergent validity was tested by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE), which should be greater than 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). However, when Cronbach’s alpha value is above 0.70, AVE values greater than 0.40 are acceptable, indicating good convergent validity (Hair et al., 2011).

Discriminant validity was tested by comparing the square root of the AVE values with the correlation values between factors. The square root values of the AVE should be higher than the correlation value between the factors whose discriminant validity is to be analyzed.

For the instrument measuring turnover intentions, as it is made up of only three factors, its validity was tested by carrying out an exploratory factor analysis. The KMO value was calculated, which should be greater than 0.70 (Sharma, 1996). We also calculated the average variance extracted, which should be greater than 50%. As for the factor weights of each item, all items with factor weights greater than 0.50 were considered.

Internal consistency was tested for each of the dimensions that make up the instrument by calculating Cronbach’s alpha, which must be greater than 0.70 (Bryman and Cramer, 2003).

Concerning the sensitivity of the items, the median, minimum, maximum, asymmetry, and kurtosis were calculated. Items should not have the median leaning against one of the extremes, and they should have responses at all points, and their absolute values of skewness and kurtosis should be below 3 and 7, respectively (Kline, 2011).

Descriptive statistics were carried out on the variables under study to see if the answers given by the participants differed significantly from the central point of the respective scale. This was done using the one-sample Student’s t-test. The association between the sociodemographic variables and the variables under study was also tested using Student’s t-tests for independent samples, one-way ANOVA and Pearson correlations.

Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 were tested using simple and multiple linear regressions. Hypothesis 6, which assumed a moderating effect, was tested using MACRO Process 4.0 developed by Hayes (2013).

3.4. Instruments

To measure occupational stress, we used the Occupational Stress Instrument - General Version (QSO-VG) by Gomes (2010), developed based on studies in different professional areas, giving it credibility for studying occupational stress. This instrument identifies and assesses potential sources of stress (i.e. stressors) in the course of work. It consists of 24 items relating to sources of stress. These items are divided into seven subscales with a 5-point Likert score (0 = no stress to 4 = much stress). The dimensions assessed are: Relationship with Patients (items 2, 8, 13 and 21); Relationship with Managers (items 12, 20 and 24); Relationship with Colleagues (items 4, 17 and 22); Overwork (items 5, 10, 11 and 16); Career and Remuneration (items 1, 6, 15 and 19); Family Problems (items 3, 14 and 23); and Working Conditions (items 7, 9 and 18). A confirmatory factor analysis was carried out on seven factors. The fit indices obtained were adequate (χ²/gl = 2.90; GFI = 0.93; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.056; SRMR = 0.045). The construct reliability of the dimensions varies between 0.85 (relationship with management) and 0.96 (family problems). Regarding convergent validity, the AVE values vary between 0.65 (relationship with managers) and 0.88 (family problems). As for divergent validity, all the AVE’s square root values are higher than the correlations between the factors for which discriminant validity is to be tested.

To measure turnover intentions, we used the instrument developed by Bozeman and Perrewé (2001), consisting of 3 items, which are anchored on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 "Strongly Disagree" to 5 "Strongly Agree"). The validity of this instrument was tested using an exploratory factor analysis. A KMO of 0.74 was obtained, which can be considered reasonable (Sharma, 1996), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at p < 0.001, which indicates that the sample comes from a multivariate population (Pestana and Gageiro). This instrument is made up of one factor, which explains 85.32% of its total variability. As for internal consistency, a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 was obtained.

The Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, developed by Demerouti and Nachreiner (1998) and adapted for the Portuguese population by Sinval et al. (2019), measured burnout. The aim is to assess the Exhaustion and Depersonalization dimensions (Halbesleben and Demerouti, 2005), in which the exhaustion subscale represents the feeling of emptiness, excessive workload, physical, cognitive, and emotional exhaustion (Demerouti et al., 2003). The depersonalization subscale reflects disengagement from the professional environment and attitudes towards work (Bakker and Demerouti (2008). This instrument consists of 16 items, which are anchored on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 "Strongly Disagree" to 5 "Strongly Agree"). These 16 items are divided into two dimensions: disengagement (items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 15) and exhaustion (items 2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16). The validity of this instrument was tested by carrying out a two-factor confirmatory factor analysis. The fit indices obtained are adequate (χ²/gl = 3.81; GFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.068; SRMR = 0.045). The construct reliability for disengagement was 0.85, and for exhaustion, 0.91. As for internal consistency, disengagement has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 and exhaustion of 0.88. Concerning convergent validity, the AVE values are 0.43 for disengagement and 0.56 for exhaustion. Although disengagement has a low AVE value, according to Hair et al. (2011), when Cronbach’s alpha value is above 0.70, values above 0.40 can be accepted. As for divergent validity, all the AVE’s square root values are higher than the correlation between the two factors.

Motivation was measured using the instrument developed by Gagné et al. (2010), consisting of 12 items anchored on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 "Strongly Disagree" to 5 "Strongly Agree"). This instrument is made up of 4 dimensions: intrinsic motivation (items 1, 2 and 3); identified motivation (items 4, 5 and 6); introjected motivation (items 7, 8 and 9); extrinsic motivation (items 10, 11 and 12). To test the validity of this instrument, a 4-factor confirmatory factor analysis was carried out. The fit indices obtained were adequate (χ²/gl = 2.76; GFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.054; SRMR = 0.033). As the extrinsic motivation dimension had very low construct reliability (0.61), very low internal consistency (0.59) and a low AVE value (0.43), it was decided to remove this dimension. A new confirmatory factor analysis was carried out. The fit indices are adequate (χ²/gl = 2.42; GFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.049; SRMR = 0.030). The construct reliability varies between 0.79 (introjected motivation) and 0.84 (intrinsic motivation). As for consistency, it varies between 0.78 (introjected motivation) and 0.86 (intrinsic motivation). Regarding convergent validity, the AVE values vary between 0.57 (introjected motivation) and 0.64 (intrinsic motivation). As for divergent validity, all the AVE’s square root values are higher than the factor correlation.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics of the variables under study

To understand the position of the answers given by the participants, descriptive statistics were carried out on the variables under study.

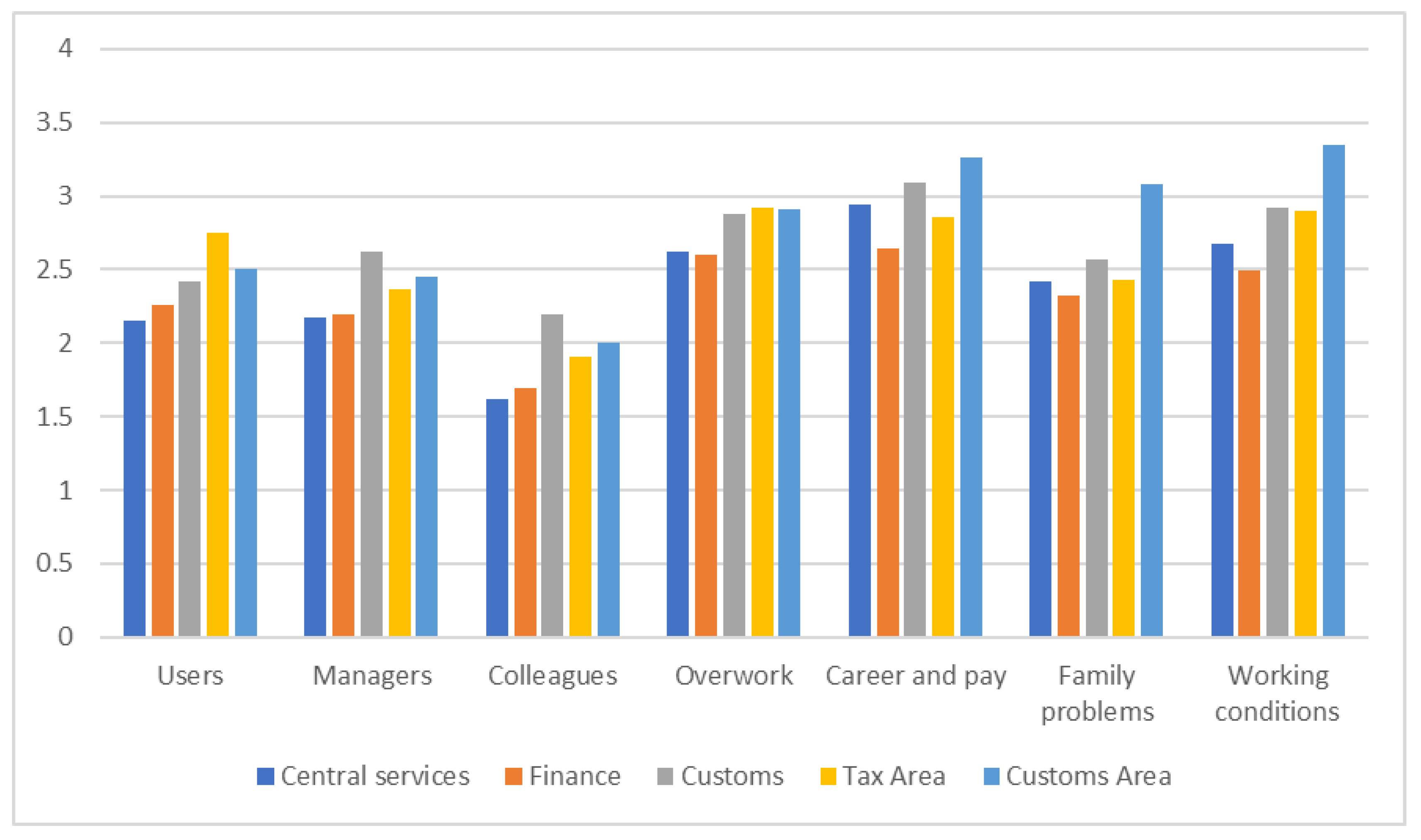

The results show that the participants in this study reported levels of stress, with all the dimensions having an average significantly higher than the central point of this scale (2), except for the "stress with colleagues" dimension (

Table 2). It was the employees working in the customs officers who showed the highest levels of stress in terms of stress about career and pay, family problems and working conditions (

Figure 2). Employees working in finance had higher levels of stress with users and with work overload (

Figure 2). Concerning stress with colleagues and managers, employees working in customs reported the highest levels (

Figure 2).

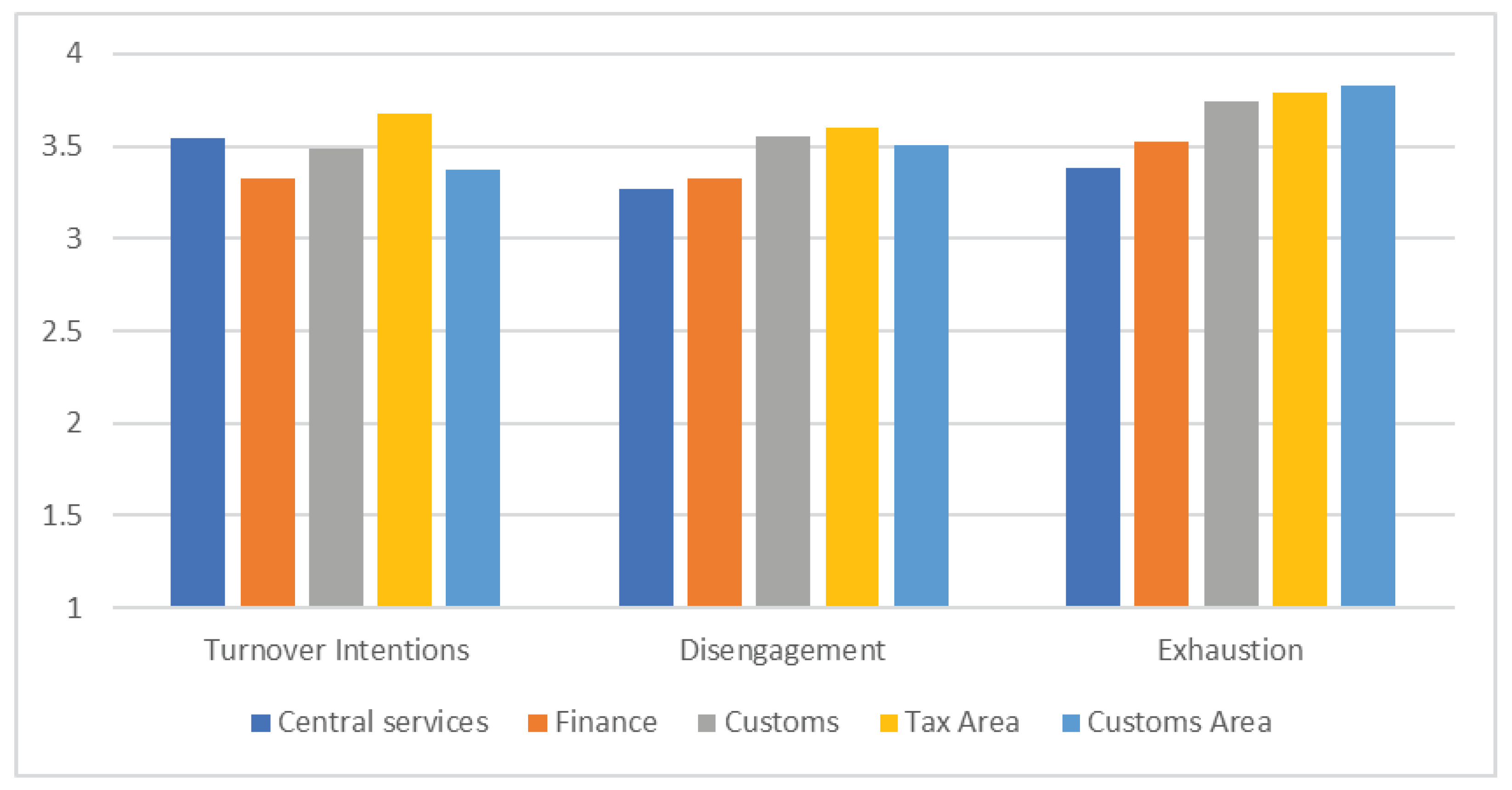

The participants also showed high turnover intentions, as well as high levels of burnout, significantly higher than the scale’s central point (3) (

Table 2). It is the participants working in financial services who have the highest turnover intentions (

Figure 3). Regarding burnout levels, participants working in the tax area reported higher levels of disengagement, and those working in the customs area reported higher levels of exhaustion (

Figure 3).

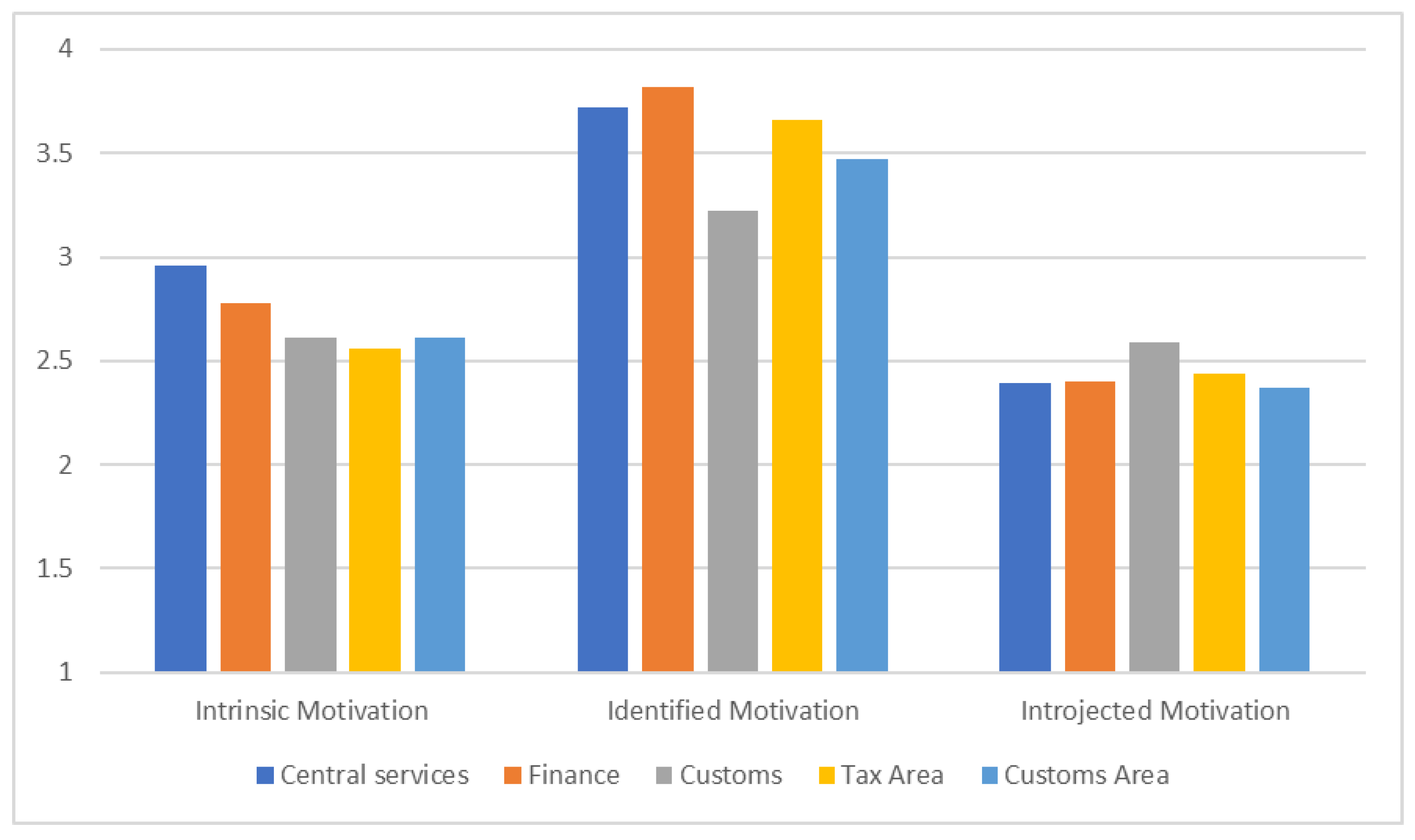

As for motivation levels, intrinsic and introjected motivation were significantly below the central point of the scale (3), while identified motivation was significantly above the central point (

Table 2). Participants working in central services reported the highest levels of intrinsic motivation (

Figure 4). As for identified motivation, the employees who reported the highest levels were those working in finance, and those who reported the lowest were those working in customs (

Figure 4). Concerning introjected motivation, the participants working in customs reported the highest levels (

Figure 4).

4.2. Association between the variables under study

The association between the variables under study was tested using Pearson’s correlations.

The results show that intrinsic and identified motivation is negatively and significantly associated with turnover intentions, disengagement, exhaustion and all the dimensions of occupational stress (

Table 3). Introjected motivation is negatively and significantly associated with turnover intentions, disengagement, and exhaustion and positively and significantly associated with family problems (

Table 3). Turnover intentions were positively and significantly associated with disengagement, exhaustion and all the dimensions of occupational stress (

Table 3). Disengagement and exhaustion are positively and significantly associated with all dimensions of occupational stress (

Table 3).

4.3. Hypothesis

To test hypothesis 1, a multiple linear regression was carried out.

The results show that only stress with the manager (β = 0.17; p = 0.001), with the workload (β = 0.21; p < 0.001) and with the career and remuneration (β = 0.15; p < 0.001) have a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions (

Table 4). The model explains 24% of the variability in turnover intentions (

Table 4). The results also indicate that the model is statistically significant (F (7, 595) = 28.30; p < 0.001) (

Table 4). Hypothesis 1 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 2 was tested by performing two multiple linear regressions.

Stress with users (β = 0.16; p < 0.001), with managers (β = 0.32; p < 0.001), with work overload (β = 0.14; p = 0.012) and with career and remuneration (β = 0.10; p = 0.012) have a positive and significant effect on disengagement (

Table 5). The model explains 29% of the variability in disengagement and is statistically significant (F (7, 595) = 35.40; p < 0.001) (

Table 5).

Stress with users (β = 0.11; p = 0.004), with managers (β = 0.17; p < 0.001), with work overload (β = 0.38; p < 0.001) and with family problems (β = 0.19; p < 0.001) have a positive and significant effect on exhaustion (

Table 5). The model explains 48% of the variability in exhaustion and is statistically significant (F (7, 595) = 79.76; p < 0.001) (

Table 5). Hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 3 was tested by performing a multiple linear regression.

Both disengagement (β = 0.52; p < 0.001) and exhaustion (β = 0.21; p < 0.001) have a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions (

Table 5). The model explains 45% of the variability in turnover intentions and is statistically significant (F (2, 600) = 249.87; p < 0.001) (

Table 6). Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Hypothesis 4, which presupposes a mediating effect, followed the assumptions of Baron and Kenny (1986). These assumptions were verified in hypotheses 1, 2 and 3. Only the mediating effects between the variables that met the three assumptions were tested. Two multiple linear regressions were carried out. In each multiple linear regressions, the predictor variables were introduced as independent variables in the first step and the mediating variable in the second step.

A total mediation effect of disengagement was proven in the relationship between stress with managers and turnover intentions (β

1 = 0.22; β

2 = 0.02) (

Table 7). After the mediating variable was introduced into the regression equation, stress with managers no longer had a significant effect on turnover intentions. Sobel’s test confirmed the total mediation effect (Z = 5.81; p < 0.001).

As for the mediating effect of disengagement on the relationship between stress over work and turnover intentions (β

1 = 0.24; β2 = 0.14), as well as on the relationship between stress over career and pay and turnover intentions (β

1 = 0.16; β2 = 0. 10), there were two partial mediation effects, since when the mediating variable was introduced into the regression equation, both overwork stress and career and pay stress continued to have a significant effect on the dependent variable, but the effect decreased in intensity (

Table 7). Sobel’s test confirmed the partial mediation effect for overwork stress (Z = 2.49; p = 0.013) and work overload, as well as career and pay stress (Z = 2.46; p = 0.013). The increase in variability proved to be significant (ΔR

2a = 0.22; p < 0.001). Both model 1 (F (3, 599) = 64.07; p < 0.001) and model 2 (F (4, 598) = 129.79; p < 0.001) were statistically significant (

Table 7).

A total mediation effect of exhaustion was proven in the relationship between work overload stress and turnover intentions (β

1 = 0.29; β

2 = 0.06) since after the mediating variable was introduced into the regression equation, work overload stress no longer had a significant effect on turnover intentions (

Table 8). Sobel’s test confirmed the total mediation effect (Z = 4.49; p < 0.001).

As for the mediating effect of exhaustion on the relationship between stress with the manager and turnover intentions (β

1 = 0.24; β

2 = 0.14), a partial mediation effect was confirmed since when the mediating variable was introduced into the regression equation, both stress with the manager continued to have a significant effect on the dependent variable, but the effect decreased in intensity (

Table 8). Sobel’s test confirmed the partial mediation effect (Z = 3.24; p = 0.001). The increase in variability proved to be significant (ΔR

2a = 0.10; p < 0.001). Both model 1 (F (2, 600) = 86.07; p < 0.001) and model 2 (F (3, 599) = 93.40; p < 0.001) were statistically significant (

Table 8).

Hypothesis 4 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 5 was tested by performing a multiple linear regression.

The results showed that intrinsic motivation (β = -0.51; p < 0.001) and identified motivation (β = -0.24; p < 0.001) have a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions (

Table 9). The model explains 40% of the variability in turnover intentions and is statistically significant (F (3, 599) = 133.76; p < 0.001). Hypothesis 5 was partially supported.

To test hypothesis 6, as it presupposes a moderation effect, the Macro Process developed by Hayes (2013) was used. Only the moderating effect of intrinsic motivation and identified motivation on the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions was tested since identified motivation has no significant effect on turnover intentions.

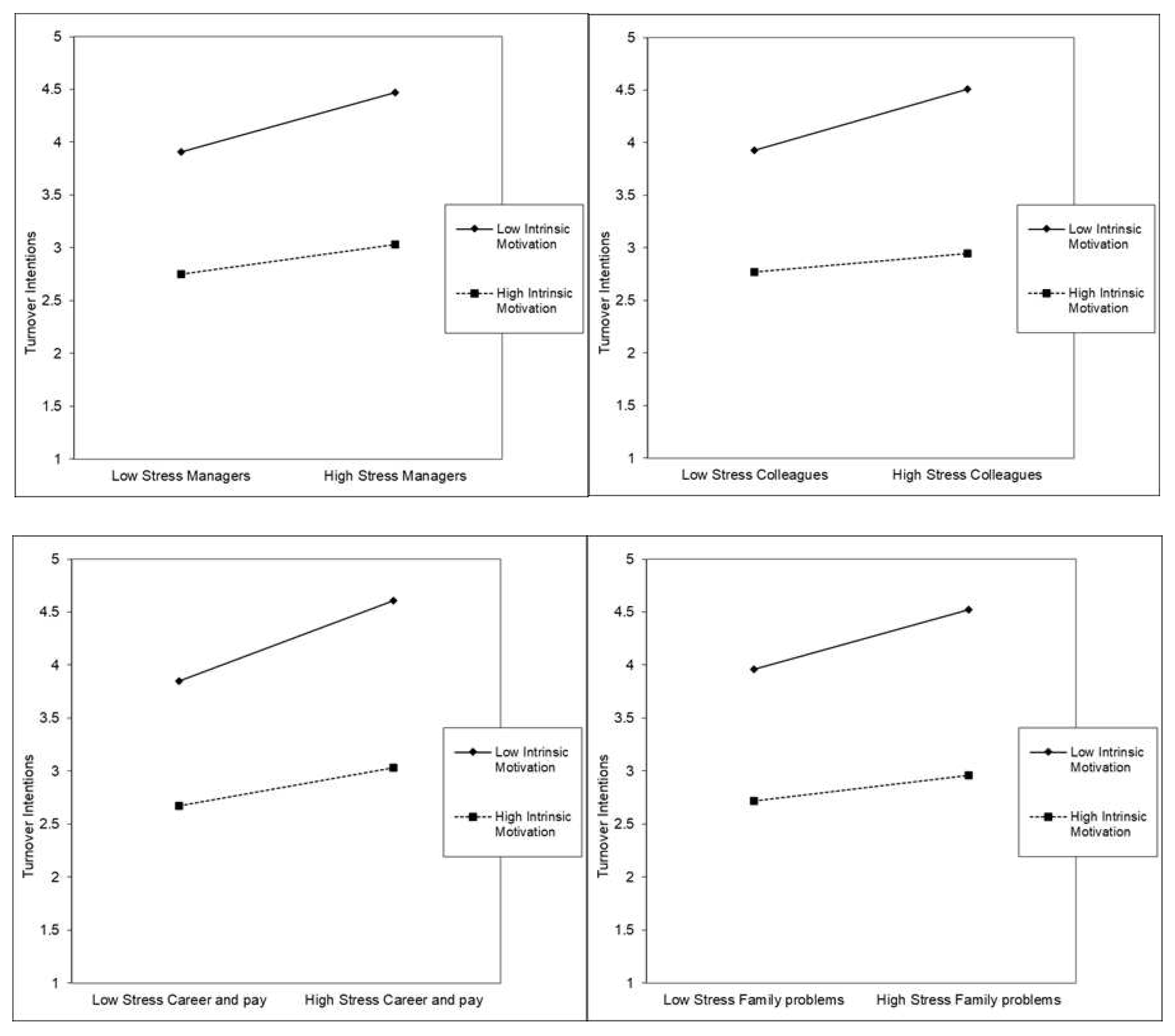

The results showed that intrinsic motivation has a moderating effect on the relationship between occupational stress (with managers, with colleagues, with career and pay and with family problems) and turnover intentions (

Table 10).

For participants with low levels of intrinsic motivation, when compared to participants with high intrinsic motivation, occupational stress (with managers, with colleagues, with career and pay and with family problems) becomes relevant to boosting their turnover intentions (

Figure 5).

There was no moderating effect of identified motivation on the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions. Hypothesis 6 was partially supported (

Table A1).

Finally, the

Table 11 summarizes the results obtained in this study.

5. Discussion

The main aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions and whether this relationship was mediated by burnout and moderated by motivation.

Hypothesis 1 was partially supported since among the dimensions of occupational stress, only stress with managers, stress with work overload, and stress with career and remuneration have a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions. These results align with the literature that occupational stress has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions (Jiang et al., 2022). The dimension of occupational stress that has the strongest effect on turnover intentions is work overload.

Hypothesis 2 was also partially supported. Stress with users, with managers, with work overload and with career and remuneration have a positive and significant effect on disengagement. It should be noted that the dimension of occupational stress that has the strongest effect on disengagement is stress with managers. Stress with users, managers, work overload and family problems have a positive and significant effect on exhaustion. The dimension of occupational stress that has the strongest effect on burnout is work overload. These results are in line with the literature since burnout occurs when employees face a stressful work environment over a long period, and there are few resources to cope with the demands of the job (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008; Maslach and Leiter, 2016; Maslach et al., 2001). From the perspective of Marques Pinto et al. (2003), burnout is a severe reaction to occupational stress.

As expected, hypothesis 3 was confirmed. Both disengagement and burnout have a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions. It should be noted that disengagement is the dimension that has the strongest effect on turnover intentions. These results are in line with what the literature tells us. According to several authors, burnout has a positive and significant effect on turnover intentions (Rahim and Cosby, 2016; Kartono and Hilmiana, 2018).

As for the mediating effect of burnout on the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions, it was found that disengagement has a total mediating effect on the relationship between stress with managers and turnover intentions and a partial mediating effect on stress with work overload and career and pay. Exhaustion has a total mediation effect on the relationship between work overload and turnover intentions and a partial mediation effect when the predictor variable is stress with managers. These results align with the literature, which states that burnout mediates the relationship between occupational stress and turnover intentions (Han et al., 2016; Salama et al., 2022).

Hypothesis 5 was partially confirmed since only intrinsic motivation and integrated motivation have a negative and significant effect on turnover intentions. These results are in line with the literature since these two dimensions are part of what is known as autonomous motivation (Lopes et al., 2022; Zheng et al. 2021).

Finally, there was evidence of the moderating effect of intrinsic motivation on the relationship between stress with managers, with colleagues, with career and remuneration and with family problems. For participants with low intrinsic motivation, when compared to participants with high intrinsic motivation, these dimensions of stress are relevant to boosting turnover intentions. These results align with the literature (Özbağ et al., 2014).

The descriptive statistics of the variables under study showed that all the dimensions of occupational stress had a mean significantly higher than the central point of the scale, except for stress with colleagues. The dimensions with the highest mean scores were stress about career and pay, work overload and working conditions. Those who showed the highest stress levels with career and pay were the employees of the customs offices, and the same was true of stress with working conditions. As for stress over workload, the highest levels were found among employees in the tax and customs offices.

Turnover Intentions were also very high, indicating that many employees are considering leaving the Tax and Customs Authority soon. This may also be because the average age of these employees is very high. The employees with the highest levels of intention to leave are those working in the tax service, but it is precisely these employees who have the highest average age.

Burnout levels are also very high, with exhaustion levels higher than disengagement levels. It should be noted that among the dimensions of occupational stress, the one that has the strongest effect on burnout is work overload, which, in turn, is one of the dimensions with the highest average. It was the employees in the customs officers who showed the highest levels of exhaustion. As for disengagement, it was the employees in the finance departments who showed the highest levels.

Concerning motivation, employees showed low levels of intrinsic motivation and introjected motivation but high levels of motivation. Employees in the finance department showed the lowest levels of intrinsic motivation, and those in the customs offices showed the highest levels of introjected motivation. Regarding identified motivation, those with the highest values are from the tax department. The low intrinsic and identified motivation in this study is in line with the results of the study conducted by Nishimura et al. (2021) with employees from the Portuguese Public Administration.

5.1. Limitations

Firstly, we have the limitation of the sampling process, which was non-probabilistic, intentional and of the snowball type.

Secondly, the type of questionnaire used in this study, a self-report questionnaire, may have biased some of the participants’ responses. However, several methodological and statistical recommendations were followed to reduce the impact of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Thirdly, it was a cross-sectional study, which does not allow us to establish causal relationships. It would be necessary to carry out a longitudinal study to test causal relationships.

6. Conclusions

This study confirmed that among the different departments of the Portuguese Tax and Customs Authority, the most critical departments are the tax offices and customs offices. Participants revealed high levels of stress, caused mainly by problems with career progression and low pay. The fact that some careers have stagnated due to the crisis in Portugal since 2008 has caused many employees to feel a sense of injustice, and their stress levels have therefore increased. Other factors that cause high levels of stress are work overload and working conditions. These high levels of stress lead to increased levels of burnout (Carod-Artal and Vázquez-Cabrera, 2013) and workers wanting to leave the organization, as some authors have pointed out (Jiang et al., 2022; Tziner et al., 2015). Those responsible for Direct State Administration through the Ministry of Finance should be concerned with restoring career progression, reducing work overload, and improving the working conditions of these employees so that levels of occupational stress are reduced, and so should burnout and turnover intentions. Another concern is the high average age of employees, which is far too high. We know that the Portuguese population is very old and that many young talents leave Portugal for other countries where job prospects are more attractive. However, the increase in the retirement age (66 years and four months) has also led to an increase in the average age of Portuguese public administration employees.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F., A. M. and F.R..; methodology, M.F. and A.M..; software, A.M.; validation, M.F., A.M. and F.R.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M.; resources, A.M.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.F., A.M. and F.R.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, M.F.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since all participants before answering the questionnaire had to read the informed consent and agree to it. This was the only way they could answer the questionnaire. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, as well as that the results were confidential, as individual results would never be known, but would only be analyzed in the set of all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available because in their informed consent, participants were informed that the data was confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Moderating effect of Identified Motivation on the relationship between Occupational Stress and Turnover Intentions.

Table A1.

Moderating effect of Identified Motivation on the relationship between Occupational Stress and Turnover Intentions.

| Variáveis |

B |

SE |

t |

p |

95% CI |

| |

Users → Turnover Intentions (R2 = 0.24; p < 0.001) |

| Constant |

3.53*** |

0.04 |

86.13*** |

< .001 |

[3.45, 3.61] |

| Users |

0.29*** |

0.04 |

6.64*** |

< .001 |

[0.20, 0.37] |

| Identified Motivation |

-0.26*** |

0.03 |

-9.51*** |

< .001 |

[-0.32, -0.21] |

| U*IdM |

0.04 |

0.03 |

1.65 |

0.099 |

[-0.08, 0.10] |

| |

Managers → Turnover Intentions (R2 = .0.24; p < 0.001) |

| Constante |

3.51*** |

0.04 |

82.79*** |

< .001 |

[3.43, 3.60] |

| Managers |

0.28*** |

0.04 |

4.04*** |

< .001 |

[0.20, 0.35] |

| Identified Motivation |

-0.23*** |

0.03 |

-8.01*** |

< .001 |

[-0.29, -0.17] |

| M*IdM |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.24 |

0.810 |

[-0.04, 0.05] |

| |

Colleagues → Turnover intentions (R2 = 0.23; p < 0.001) |

| Constante |

3.52*** |

0.04 |

85.47*** |

< 0.001 |

[3.45, 3.61] |

| Colleagues |

0.23*** |

0.03 |

5.96*** |

< 0.001 |

[0.16, 0.31] |

| Identified Motivation |

-0.27*** |

0.03 |

-9.71*** |

< 0.001 |

[-0.32, -0.21] |

| C*IdM |

0.04 |

0.02 |

1.65 |

0.100 |

[-0.01, 0.09] |

| |

Overwork → Turnover Intentions (R2 = 0.26; p < 0.001) |

| Constante |

3.52*** |

0.04 |

85.31*** |

< 0.001 |

[3.44, 3.60] |

| Overwork |

0.37*** |

0.05 |

7.84*** |

< 0.001 |

[0.28, 0.47] |

| Identified Motivation |

-0.23*** |

0.03 |

-8.39*** |

< 0.001 |

[-0.29, -0.18] |

| O*IdM |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.99 |

0.321 |

[-0.03, 0.09] |

| |

Career and pay → Turnover Intentions (R2 = 0.21; p < 0.001) |

| Constante |

3.52*** |

0.05 |

77.23*** |

< 0.001 |

[3.42, 3.60] |

| Career and pay |

0.22*** |

0.05 |

4.07*** |

< 0.001 |

[0.11, 0.32] |

| Identified Motivation |

-0.25*** |

0.03 |

-7.90*** |

< 0.001 |

[-0.31, -0.19] |

| CP*IdM |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.17 |

0.862 |

[0.06, 0.07] |

| |

Family problems → Turnover Intentions (R2 = 0.22; p < 0.001) |

| Constante |

3.52*** |

0.04 |

83.49*** |

< 0.001 |

[3.45, 3.61] |

| Family problems |

0.19*** |

0.03 |

4.85*** |

< 0.001 |

[0.12, 0.27] |

| Identified Motivation |

-0.27*** |

0.03 |

-9.43*** |

< 0.001 |

[-0.32, -0.21] |

| FP*IdM |

0.03 |

0.02 |

1.37 |

0.173 |

[-0.01, 0.08] |

| |

Work conditions→ Turnover Intentions (R2 = 0.21; p < 0.001) |

| Constante |

3.52*** |

0.04 |

80.37*** |

< 0.001 |

[3.44, 3.61] |

| Work conditions |

0.21*** |

0.05 |

4.53*** |

< 0.001 |

[0.12, 0.30] |

| Identified Motivation |

-0.26*** |

0.03 |

-8.60*** |

< 0.001 |

[-0.31, -0.20] |

| WC*IdM |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.82 |

0.412 |

[-0.03, 0.08] |

References

- (Avey et al., 2009) Avey, James B., Fred Luthans, and Susan M. Jensen. 2009. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manage., 48, 677-693. [CrossRef]

- (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008) Bakker, A.rnold B., Evangelia Demerouti. 2008. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13 (3), 209-223. [CrossRef]

- (Benson, 2006) Benson, George S. 2006. Employee development, commitment and intention to turnover: A test of “employability” policies in action. Human Resource Management Journal 16, 173–92. [CrossRef]

- (Bicho and Pereira, 2007) Bicho, L. M. D., and Pereira, S. R. 2007. Stress ocupacional. Stress Ocupacional. Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, Departamento de Engenharia Civil, Portugal.

- (Bozeman and Perrewé, 2001) Bozeman, Dennis P., and Pamela Perrewé. 2001. The effect of item content overlap on organizational commitment questionnaire – turnover cognitions relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 161-173. [CrossRef]

- (Bryman and Cramer 2003) Bryman, Alan., and Duncan. Cramer. 2003. Análise de dados em ciências sociais. Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS para windows, 3rd ed. Oeiras: Celta.

- (Carod-Artal and Vázquez-Cabrera, 2013) Carod-Artal, Francisco J., and Carolina Vázquez-Cabrera. 2013. Burnout syndrome in an international setting. In S. Bährer-Kohler (Ed.), Burnout for experts: Prevention in the context of living and working (pp. 15–35). Springer Science + Business Media. [CrossRef]

- (Demerouti and Nachreiner, 1998) Demerouti, Evangelia, and Friedhelm Nachreiner. 1998. Zur spezifität von burnout für dienstleistungsberufe: Fakt oder artefakt? [The specificity of burnout in human services: Fact or artifact?]. Z. Arbeitswiss, 52, 82–89.

- (Demerouti et al., 2001) Demerouti, Evangelia, Bakker, Arnold B., Friedhelm Nachreiner, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2001. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [CrossRef]

- (Demerouti et al., 2003) Demerouti, Evangelia, Bakker, Arnold B.; Ioanna Vardakou, and Aristotelis Kantas. 2003. The Convergent Validity of Two Burnout Instruments. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19, 12-23. [CrossRef]

- (Fornell and Larcker, 1981) Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- (Gagné et al., 2015) Gagné, Marylène, Jacques Forest, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Laurence Crevier-Braud, Anja van den Broeck, Ann Kristin Aspeli, Jenny Bellerose, Charles Benabou, Emanuela Chemolli, Stefan Tomas Güntert, Hallgeir Halvari, Devani Laksmi Indiyastuti, Peter A. Johnson, Marianne H. Molstad, Mathias Naudin, Assane Ndao, Anja Hagen Olafsen, Patrice Roussel, Zheni Wang, and Cathrine Westbye. 2015. The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24(2), 178–196. [CrossRef]

- (Gagné et al., 2010) Gagné, Marylène, Jacques Forest, Marie Hélène Gilbert, Caroline Aubé, Estelle Morin, and Angela Malorni. 2010. The Motivation at Work Scale: Validation Evidence in Two Languages. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(4), 628-646. [CrossRef]

- (Gomes, 2010) Gomes, Rui A. (2010). Questionário de Stress Ocupacional – Versão Geral. Relatório Técnico, Universidade do Minho.

- (Grohmann et al., 2013) Grohmann, M. Z., Cunha, L. D., & Silinske, J. (2013). Relações entre motivação, satisfação, comprometimento e desempenho no trabalho: estudo em um Hospital Público. IV Encontro de Gestão de Pessoas e Relações de Trabalho, Brasília/DF, 3.

- (Hair et al., 2011) Hair, Joseph, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19, 139-151. [CrossRef]

- (Halbesleben and Demerouti, 2005) Halbesleben, Jonathon R. B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2005.The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: Investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. Work & Stress, 19(3), 208–220. [CrossRef]

- (Han et al., 2016) Han, Su Jin, Mark Bonn, and Meehee Cho. 2016. The relationship between customer incivility, restaurant frontline service employee burnout and turnover intention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 52, 97-106. [CrossRef]

- (Hayes, 2013) Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- (Hu and Bentler 1999) Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [CrossRef]

- (Hussain et al., 2018) Hussain, Syed Talib, Shen Lei, Tayyaba Akram, M. Jamal Haider, Hussain, Syed Hadi, and Muhammad. 2018. Kurt Lewin’s Process Model for Organizational Change: The Role of Leadership and Employee Involvement: A Critical Review. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 3, 123-127. [CrossRef]

- (Jesus et al., 2023) Jesus, Alexandra, Liliana Pitacho, and Ana Moreira. 2023. Burnout and Suicidal Behaviours in Health Professionals in Portugal: The Moderating Effect of Self-Esteem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 20, 4325. [CrossRef]

- (Jiang et al., 2022) Jiang, Nan, Hongling Zhang, Zhen Tan, Yanhong Gong, Mengee Tian, Yafei Wu, Jiali Zhang, Jing Wang, Zhenyuan Chen, Jianxiong Wu, Chuanzhu Lv, Xuan Zhou, Fengjie Yang, and Xiaoxv Yin (2022) The Relationship Between Occupational Stress and Turnover Intention Among Emergency Physicians: A Mediation Analysis. Front. Public Health 10:901251. [CrossRef]

- (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993) Jöreskog, Karl. G., and Dag. Sörbom. 1993. LISREL8: Structural Equation Modelling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International.

- (Kartono and Hilmiana, 2018) Kartono, Kartono, and Y. Hilmiana, 2018. Job Burnout: A Mediation between Emotional Intelligence and Turnover Intention. Jurnal Bisnis Dan Manajemen, 19(2), 109–121. [CrossRef]

- (Kline, 2011) Kline, Rex B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- (Leiter, 1998) Leiter, Michael P. 1998. Burnout as a Function of Communication Patterns: A Study of a Multidisciplinary Mental Health Team. Group & Organization Management, 13(1), 111–128. [CrossRef]

- (Leiter and Maslach, 2016) Leiter, Michael P., and Christina Maslach. 2016. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Research, 3(4), 89–100. [CrossRef]

- (Long et al., 2012) Long, C., Perumal, P., and Ajagbe, M. 2012. The impact of human resource management practices on employees’ turnover intention: A conceptual model. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 4, 629-641.

- (Lopes et al., 2022) Lopes, Silvia, Ana Sabino, Paulo C. Dias, Anabela Rodrigues, Maria José Chambel, and Francisco Cesário. 2022. Through the Lens of Workers’ Motivation: Does It Relate to Work–Family Relationship Perceptions? Sustainability 14, 16117. [CrossRef]

- (Marques-Pinto et al., 2003) Marques-Pinto, A., Lima, M. L., and Lopes da Silva. 2003. Stress Profissional em Professores Portugueses: incidência, preditores e reação de burnout. Psicologia, 33, 181-194.

- (Maslach and Leiter, 2016) Maslach, Christina, and Michael P. Leiter. 2016. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. [CrossRef]

- (Maslach et al., 2001) Maslach, Christina, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, Michael P. Leiter. 2001. Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397-422.

- (Maslow, 2000) Maslow, Abraham Harold (2000). Maslow no gerenciamento. Rio de Janeiro: Qualitymark Editora.

- (Meier, 1984) Meier, S. The construct validity of burnout. Journal of Occupational Psychology 1984, 57(3), 211–219. [CrossRef]

- (Moreira et al., 2022) Moreira, Ana, Maria José Sousa, and Francisco Cesário. 2022. Competencies development: The role of organizational commitment and the perception of employability. Social Sciences 11: 125. [CrossRef]

- (Nishimura et al., 2021) Nishimura, Adriana Z. F. C., Ana Moreira, Maria José Sousa, and Manuel Au-Yong-Oliveira. 2021. Weaknesses in Motivation and in Establishing a Meritocratic System: A Portrait of the Portuguese Public Administration. Administrative Sciences 11: 87. [CrossRef]

- (Olivares-Faúndez et al., 2014) Olivares-Faúndez, Victor E., Pedro R. Gil-Monte, Luís Mena, Carolina Jélvez-Wilke, and Hugo Figueiredo-Ferraz. 2014. Relationships between burnout and role ambiguity, role conflict and employee absenteeism among health workers. Terapia Psicológica, 32(2), 111–120. [CrossRef]

- (Özbağ et al., 2014) Özbağ, Gönül Kaya; Ceyhun, Gökçe Çicek; Çekmecelioğlu, Hülya Gündüz. 2014. The Moderating Effects of Motivating Job Characteristics on the Relationship between Burnout and Turnover Intention. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150, 438–446. [CrossRef]

- (Park and Shaw, 2013) Park, T., and Shaw, J. 2013. Turnover rates and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 268-309. [CrossRef]

- (Pestana and Gageiro, 2003) Pestana, Maria Helena, and Gageiro, João Nunes. 2003. Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais – A complementaridade do SPSS (3ª ed.). Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

- (Podsakoff et al. 2003) Podsakoff, Phillip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong Y. Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [CrossRef]

- (Poghosyan et al., 2010) Poghosyan, Lusine, Sean P. Clarke, Mary Finlayson, and Linda H. Aiken. 2010. Nurse burnout and quality of care: Cross-national investigation in six countries. Res. Nurs. Health, 33: 288-298. [CrossRef]

- (Rahim and Cosby, 2016) Rahim, Afzalur, and Dana M. Cosby. 2016. A model of workplace incivility, job burnout, turnover intentions, and job performance. Journal of Management Development, 35(10), 1255–1265. [CrossRef]

- (Reiche, 2008) Reiche, B. Sebastian. 2008. The Configuration of Employee retention practices in multinational corporations’ foreign subsidiaries. International Business Review 17: 676–87.

- (Salama et al. 2022) Salama, Wagid, Ahmed H. Abdou, Shaimaa A. K. Mohamed, and Hossam S. Shehata. 2022. Impact of Work Stress and Job Burnout on Turnover Intentions among Hotel Employees. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(15), 9724. [CrossRef]

- (Silva and Gomes, 2009) Silva, Maria da Conceição M., and Rui Gomes. 2009. Stress ocupacional em profissionais de saúde: um estudo com médicos e enfermeiros portugueses. Estudos de Psicologia (Natal), 14, 239-248. [CrossRef]

- (Sinval et al., 2019) Sinval, Jorge, Cristina Queirós, Sonia Pasian, and João Marôco. 2019. Transcultural Adaptation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) for Brazil and Portugal. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 338. [CrossRef]

- (Tamayo and Paschoal, 2003) Tamayo, Álvaro, and Tatiane Paschoal. 2003. A relação da motivação para o trabalho com as metas do trabalhador. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 7(4), 33-54. [CrossRef]

- (Trochim 2000) Trochim, William. 2000. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Atomic Dog Publishing.

- (Tziner et al., 2015) Tziner, A., Rabenu, E., Radomski, R., & Belkin, A. 2015. Work stress and turnover intentions among hospital physicians: The mediating role of burnout and work satisfaction. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(3), 207–213. [CrossRef]

- (Wang et al., 2019) Wang, Enjian, Hongwei Hu, Shan Mao, and Hongting Liu. 2019. Intrinsic motivation and turnover intention among geriatric nurses employed in nursing homes: the roles of job burnout and pay satisfaction, Contemporary Nurse, 55:2-3, 195-210. [CrossRef]

- (Zheng et al., 2021) Zheng, Junwei, Xueqin Gou, Hongyang Li, and Hongtao Xie. 2021. Differences in Mechanisms Linking Motivation and Turnover Intention for Public and Private Employees: Evidence From China. SAGE Open, 11(3). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).