1. Introduction

Recent events across the world have meant that economies need to reassess and readjust to the “business as usual” narrative. Since the latter part of December 2019, and more instructively in the first quarter of 2020, the manner in which business is conducted has witnessed a major reawakening. The novel coronavirus (or COVID-19) has highlighted weaknesses, and/or fractures in the status quo and the way business is conducted globally. This has brought about what many have described as a “new normal” with impact on both lives and livelihoods of businesses – especially those in the MSME sector. Retracing the experience of 1918 flu pandemic, and the recent novel coronavirus or COVID-19, the devastating effects on human lives and the global economy have been considerable (Karlsson et al., 2014; Kabir et al., 2020), but not surmountable. As of 25 October 2023, confirmed COVID-19 cases were approximately 771, 549, 718 of which about 6, 974, 473 lives had been lost at the global level due to the pandemic (WHO, 2023).

These figures are not only magnanimous, but rather unsettling in terms of their scale and significance. A particular consequence of the situation are the crippling of businesses, recalibration of global growth estimates coupled with the economic loss and the sudden changes in the dynamics of consumer behaviour and consumption patterns, which have prompted a range of actions, reactions and reassessment of global business conduct (Adeyanju et al, 2022; Li-Ying & Nell, 2020; Rapaccini et al, 2020;)

Given the indispensable role of MSMEs to the growth estimates of the global economy, this study highlights how the sector has been pivotal to meeting the needs of consumers vis-à-vis their value perceptions and changes in these, within the rather volatile business environment. This is linked to the view to rebooting that direction of travel as the global economy struggles to cope with the volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (i.e., VUCA).

Accordingly, the main purpose of this conceptual paper is to highlight some of the challenges confronting MSMEs, especially in times of, and not just in the aftermath of COVID-19. The study, therefore, reflects upon a range of dynamics including the role and place of key stakeholders coerced into the adoption of digital technologies with a view to positioning them for kick starting and/or restarting the global economy. This overarching message in the study is a subject matter that has gained traction in pre-COVID-19 times, but now become more urgent under the current crisis times.

Overall, this study addresses what actions need to be undertaken in order to sustain the bottom-line of businesses – notably MSMEs following the ongoing crisis. Consequently, the main objectives of the study are to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the face of the global economy since the first quarter of 2020; review the impact of the pandemic on the efforts of MSMEs navigating the challenges and opportunities by ‘pivoting’ and embracing the mantra of ‘value co-creation’ with consumers; and more instructively, highlight how MSMEs could be better positioned towards rebooting the global economy – notably through the adoption and deployment of the world of digital and what opportunities it provides.

Following this opening section, the study delves into the current state of affairs of the global economy in a Covid-19 era. It then interrogates the intersections between entrepreneurship, MSMEs and economic growth in the third section. This interrogation moves on to the conversation on the challenges and opportunities of “explorations of value-co-creation in a digital age,” in section 4. This is closely followed up in section 5 with a discussion of the global pandemic, and how it seems to have, unexpectedly forced different organizations irrespective of their sizes to instantly pivot to a digital-only approach. Examples of organisations having to abandone the 2020 playbook and embrace new strategies and modalities are also highlighted in this section. The sixth and seventh sections cover practical implications and conclusions in respective order.

2. COVID-19 and the Global Economy

The outbreak of the new coronavirus in China and reported by Word Health Organization (WHO) in December 2019 is now a global pandemic with considerable impacts in virtually all occupations. The WHO labelled it COVID-19 on 11 February 2019 (McAleer, 2020) and this now resonates with various aspects of the global business environment. Hence, entrepreneurship has been affected in a significant way all over the world. Although this is a recent phenomenon, it has attracted some scholarship effort (Chang and Velasco, 2020; Baker et al., 2020). The study by Kabir et al. (2020) on pandemic economic cost indicates that the cost of the pandemic to the global economic system is estimated to be US$1 trillion. Others have pointed out that it influences businesses including the financial markets as the lockdowns have affected the demand and supply chains (Nicola et al., 2020).

It is a clear colossal shock, which indicates a link between medical and economic policies (Chang and Velasco, 2020). Its impact on employment is palpable as millions of jobs have been lost while many have concerns about future concerning their employment (Fetzer et al., 2020; Coibion et al., 2020). As the pandemic continues to hit the economy, households continue to take drastic steps in terms of their consumption activities (Baker et al., 2020). One of these changes in the pattern of consumption is the surge in the demand experienced by the food sector as people engage in stockpiling because of panic buying (Nicola et al., 2020). In addition to this, there is a significant increase in internet searchers all over the world (Fetzer et al., 2020; Coibion et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the need to rebuild the global economy is not only very compelling but also urgent to restore a heathy marketing system for both the customers and the MSMEs. A new approach would be needed in a ‘new normal’ marketing environment for sustainable global business environment.

3. Entrepreneurship, MSMEs and Economic growth

Entrepreneurship as well as micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) constitute much of the economic growth noted in industrialized countries (Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004; Raward, 2004; Gbadamosi, 2015: 2019a; Lounsbury et al., 2019). Nonetheless, as Gibb (1996, p. 310) once pointed out, the growth of interest in small business is not restricted to only Western European or United States. In developing nations, small business development has become a crucial focus in strategic adjustment programmes as MSMEs constitute around t 70 percent of the formal economy and approximately 90 percent of the total employment of the developing world (El Tarabishy, 2020).

Arguably, MSMEs present a classic sector for the beginning gof creating and disseminating newly created systems that aid the local community while working from a World Economy perspective. In the current COVID-19 climate, people’s social, financial and humanitarian needs have been projected like never before. In crisis times such as this, it is evident that MSMEs are more at risk, as most tend to operate in customer facing environments requiring constant human interactions – from restaurants, cafes and bars to minicabs, delivery services and grooming services such as barbershops and/or hairdressing. With the lockdowns across the world, the operations of these high-contact services is no longer feasible and both lives and livelihoods have become threatened (see Igwe et al. 2019).

In a recent opinion article, Andrew Reid, Founder and CEO, Rival Technologies indicates that one of the ways to navigate the COVID-19 environment/pandemic is the ability to remain agile for the new normal (Reid, 2020). According to him, some marketers and entrepreneurs are delaying taking some actions, with the thought that things would return to “normal” soon. Meanwhile a more important acknowledgement is the fact that the conundrum will have an enduring and long-term impact on the psyche and outlook of shoppers.

In yet another recent COVID-19 study, it was pointed out that the crisis would create a “now normal,” and have an enduring effect on society. What this means is that in a post-COVID-19 era, firms cannot go back to their former playbooks. Messaging, personas and even product strategies may need to drastically change to be consistent with the realities of the post- COVID-19 world (El Tarabishy, 2020). One sector that seems to be reimagining itself in a period of lockdown is the creative economy (encompassing theatres, museums and the music sector) where there have been indications of a bounce back (see Madichie, 2020; Madichie & Agu, 2023). In a recent Forbes article (Grant, 2020), for example, it was pointed out that due to the pandemic, the the music industry has been forced to be creative, making it necessary for artists to integrate new types of of media into their routine for the purpose of maintaining and growing an engaged audience. In the end, this may just be exactly what the industry needs to keep and grow consumer attention. Besides, what people need in these crisis times is some indication of upliftment, which music provides and we have seen to transition towards digital performances across the globe.

In the 2019 report of the International Council for Small Business (ICSB), entrepreneurship was argued to be linked to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 and 8. Specifically the target of SDG 4.4 “aims to substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment and decent jobs and entrepreneurship” (Carpentier, 2019, p. 34). As for SDG 8, the emphasis is to to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.” However, the question now is how this can be done effectively pivoted for a post COVID-19 world, and addressing the notion of customer value, which underpin a sustainable marketing system.

Using data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) survey, Devece, Peris-Ortiz & Rueda-Armengot (2016) identify combinations of essential entrepreneurial factors that prompted the development of new businesses under different economic circumstances – taking Spain as a case illustration. These authors explored the 2008 economic situations (crisis and boom) prior to this downturn and revealed that “necessity-driven entrepreneurship” was useless during the times of recession and that “innovation and opportunity recognition” appeared more relevant as success factors during recession than during times of prosperity (see Devece et al., 2016, p. 5366).

In spite of its richness, extant literature does not offer a unanimous perspective on how the environment (both scial and economic) affects the dynamics of early entrepreneurship and the profile of the dominant entrepreneurial system. Put differently, economic and factors, R & D transfer, governmental support and policies, and regional infrastructures interact, such that the Total Early-Stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA) may be more analogous in nations with disparate profiles than in countries that have similar stages of socioeconomic development (Simon-Moya et al., 2014; Devece et al., 2016, p. 5367).

Push and pull factors are worth highlighting. On the one hand, economic crises are typically push factors, i.e., those external conditions that force people into entrepreneurship in the absence of alternative employment choices. Besides unemployment, “push factors” include searching for autonomy and difficulties in finding work due to demographic disadvantages including ethnicity, social class, and educational background among others (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2011; Madichie, 2009). Economic crises which are associated with high unemployment may push people toward self-employment due to the absence of other opportunities.

On the other hand, “pull factors” attract entrepreneurs to engage in businesses creation in order to seize market opportunities (Devece et al., 2016, p. 5367). Put differently, business venturing emanating from the “pull” are similar to opportunity recognition and this resonates with “pivoting”. The attraction from this perspective is not borne out of a need to survive, but to take advantage of an opportunity such as what has been witnessed in crises. In the context of COVID-19, for instance, the pull has been epitomized by the likes of fashion businesses ditching garments for the production of personal protective equipment (or PPE) and face masks. Similarly, manufacturers of alcoholic beverages have turned to the production of hand sanitisers.

Indeed, the literature (Madichie, 2020; Morgan et al., 2020; Carpentier, 2019; Devece et al., 2016) seems to suggest that entrepreneurship has proven to achieve better results in times of recession (or crisis) as opposed to boom times. This revelation is nothing new, as Fairlie (2013) once pointed out, while entrepreneurial ventures are not many during the periods of recession, they tend to perform better when considered from the viewpoint of quality and growth (in relation to job creation and size)– albeit with some characteristics in place. One of such features is capacity as may be the cases with tailors pivoting to PPE and facemasks rather than traditional fashion apparel.

Pivoting remains one of the relevant phrases that resonates with opportunity recognition and may be considered central to navigating crisis times like the recent COVID-19 pandemic. As Morgan et al. (2020) point out, pivoting represents a situationin which small firms can promptly alter their products, services or mode of delivering them to leverage off the opportunities offered by the virus.” Pivoting has also been defined as ‘a structured course correction designed to test a new fundamental hypothesis’ (Ries, 2011, p. 149). In other words, it is about doing a purposeful search through the guidance of of evidence of a profoundly better entrepreneurial opportunity that the organization can competently exploit. Hence, it is not every action taken by a struggling entrepreneur that can be regarded as a meaningful pivot.

Only recently, Morgan et al. (2020, p. 2) point out, that “pivoting may be beneficial, and popular media abounds with examples of firms that have successfully repositioned themselves in response to exogenous shocks.” It is worth adding, however, that it is not every change that can be classified as a pivot, and those major changes that take place as a result pivoting come at a cost. These authors argue further that “the new opportunities that have been discovered may be of inferior quality for the organization in question, they may be unsustainable and the firm may not be well-positioned to take advantage of them.

Morgan et al (2020) reported on the swift and negative impact of the global pandemic upon entrepreneurial behaviour, innovation, and MSME performance following a collection of a number of short commentaries as a form of reflection on the potential implications of the pandemic. That study highlighted a range of issues from finance, innovation, pivoting to policy. These attributes or activities were central to developing valuable thought upon how the quick, and mostly negative effects in contemporary markets, would impact entrepreneurs and their inventments.

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only disrupted global supply chains, but also brought in its wake other logistical challenges, extreme price distortions, collapse of businesses and markets, consumer apathy towards government, erosion of trust in global trade policies, and the need to redesign the work processes (see for example, Valinsky, 2020; Hudecheck et al. 2020). Going forward, the challenges associated with forecasting the duration of the crisis led many existing firms to consider pivoting, and changing their market offerings customers or markets. However, this conversation around pivoting cannot be disentangled from value-adding activity for both vendor and end user, which leads into the need to revisit value co-creation both in the short and medium term.

4. Value-co-creation in a digital age: Challenges and opportunities

The notion of value is very central to contemporary marketing practice. Interestingly, what constitutes value varies between consumer groups and could change over time. While there are many definitions of value offered in the academic literature, one of these that has a wider relevance defines it as the difference between the perceived benefits and the costs associated with a particular transaction which could be in the form of money, emotion, and time (Solomon, et al., 2013; Gbadamosi, 2019b). Hence, it is widely acknowledged that consumers’ interest in any product or service would be driven by this value, which indicates that marketers are expected to be focused on this value to satisfy the customers and ensure business sustainability (Zeithaml, 1988; Saha et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020).

Meanwhile, a cursory look at this would put the responsibility of value creation solely on the shoulder of businesses. Nonetheless, a number of seminal papers (Vargo and Lusch, 2004; 2008; Grönroos, 2008; Prahalad and Ramaswany, 2004) have indicated that businesses cannot deliver this value by themselves but will have to involve customers in the process known as ‘value co-creation. This then brings in the customers as active participants in ensuring that the needed value is created, delivered and managed effectively.

The experience that characterized COVID-19 has obviously been very challenging for both businesses and customers alike. The impact is evident in the activities of SMEs as well as large corporations. This has significantly challenged the stability of global economic systems. Consequently, the notion of value co-creation is challenged largely as the activities of both key parties involved in a value creation are crippled. This is evident in various ways such as in the form of locked restaurants and pubs, deserted high streets, and empty beaches, which in turn renders the services of hotels and tourism system unprofitable as they are confronted with the challenge of maintaining social distancing policy to save lives. These are some of the numerous challenges associated with this prevailing COVID-19 conundrum.

Prior to the global pandemic, the scope of the notion of value co-creation has widened significantly with the application of digital technologies in many aspects of consumer decision making process which constitutes the key framework in how businesses can satisfy its customers. Conventionally, the extant literature (Engel et al. 1968; Kotler and Armstrong, 2018) acknowledges that consumers pass through various stages before they make the final product. These include need recognition, information search, alternatives evaluation, purchase decision/act and post-purchase evaluation. Each of these stages has been significantly enhanced by the use of digital technologies. For example, the use of the internet and social media has linked consumers globally implying that their needs for products and services could be influenced from anywhere all over the world, they can also search for information relating to options they have on which products/brands could be used to satisfy their needs, and they are more equipped to evaluate these through the development in the digital world. Similarly, a plethora of evidence shows that actual purchase can take place with digital technologies as aided by various delivery systems while post-purchase evaluation also showing satisfaction or dissatisfaction are also increasingly facilitated by electronic means.

In the current dispensation, lockdown policies that characterize the global pandemic have, for better or for worse, strengthened the use of digital technologies for facilitating consumption in unprecedented scale. The global internet usage as of April 2022 is indicated as 5 billion (Statista, 2022) while the one for 2021 and 2020 were given as 4.9 billion and 4.6 billion respectively (Statista, 2021). This is a global business opportunity that will have to drive consumption and business activities for a long time. Hence, despite the challenges, great opportunities still abound within the current crisis environment. Consequently, value-co-creation and pivoting remain two of the promising response strategies for businesses not just post-COVID-19, but also in the turbulent business environment currently being dictated by the global pandemic.

5. Discussion

The impact of COVID-19 has prompted organisations across sectors – for-profit, public sector, as well as nonprofit organizations of all sizes to pivot to digital and/or remote touchpoints. This discontinuation of in-person events and face-to-face interactions have brought to the fore the previously taken for granted world of work. Almost overnight, organizations in key sectors such as health, social care, legal services, educational and cultural institutions were faced with a common challenge, which required doing away with the pre-pandemic playbook and devising new strategies and modalities to remain connected with their diverse set of stakeholders.

In the face of shrinking and tighter promotional and advertising budgets another layer of urgency to organisational operations and performance was the pandemic. What the world witnessed post-2020 was a wave of innovation and experimentation in organisations across sectors, as digital became the new mantra of business model pivoting (see Morgan, Anokhin, Ofstein & Friske, 2020).

As Morgan et al., (2020) alluded to recently, there are always “bright and dark sides of business model pivoting,” and these are usually more pronounced in times of “…major exogenous shocks.” Accordingly, while much of our thinking was influenced by the COVID-19 crisis how the advice would be applied goes well beyond this specific event. “ It is our hope to encourage the dialogue along these lines with our fellow scholars, and our obligation to inform both policymakers and decision makers of the dangers inherent in trying to develop the one-size-fits-all approach to deal with exogenous shocks” (Morgan et al, 2020, p. 8).

Interestingly, Fairlie (2013, p. 208) pointed out that “the recent recession might have increased “necessity” entrepreneurship or business creation because of the rapid rise in the number of layoffs and unemployment in the United States”. Extant literature indicates that job loss and reduced labour market opportunities result in self-employed business ownership (Farber, 1999; Parker, 2009; Krashinsky, 2005; Fairlie, 2013). According to these authors, while the the motivation for starting a the business in this case might be different, several of these establishments may eventually turn out to be very successful.” In that study, Stangler (2009) was reported to having found that most Fortune 500 businesses were started during periods of recession.

As Fairlie (2013) points out, on the one hand, while the ‘Great Recession’ has led tomany business closings and foreclosures, it is important to ask the question of what effect did it have on business formation? In one aspect, recessions resulted in the decrease of probable business revenue and wealth, and in another way, they limit opportunities in the wage/salary sector and make the net effect on entrepreneurship to be ambiguous (Fairlie, 2013,). As the study seems to indicate, “the results show a consistent outlook of the positive impacts of slack labour markets outweighing the negative influences and resulting in higher levels of business formation and the predicted trend in entrepreneurship rates tracks the actual increase in entrepreneurship very well during the Great Recession.

6. Practical Implications

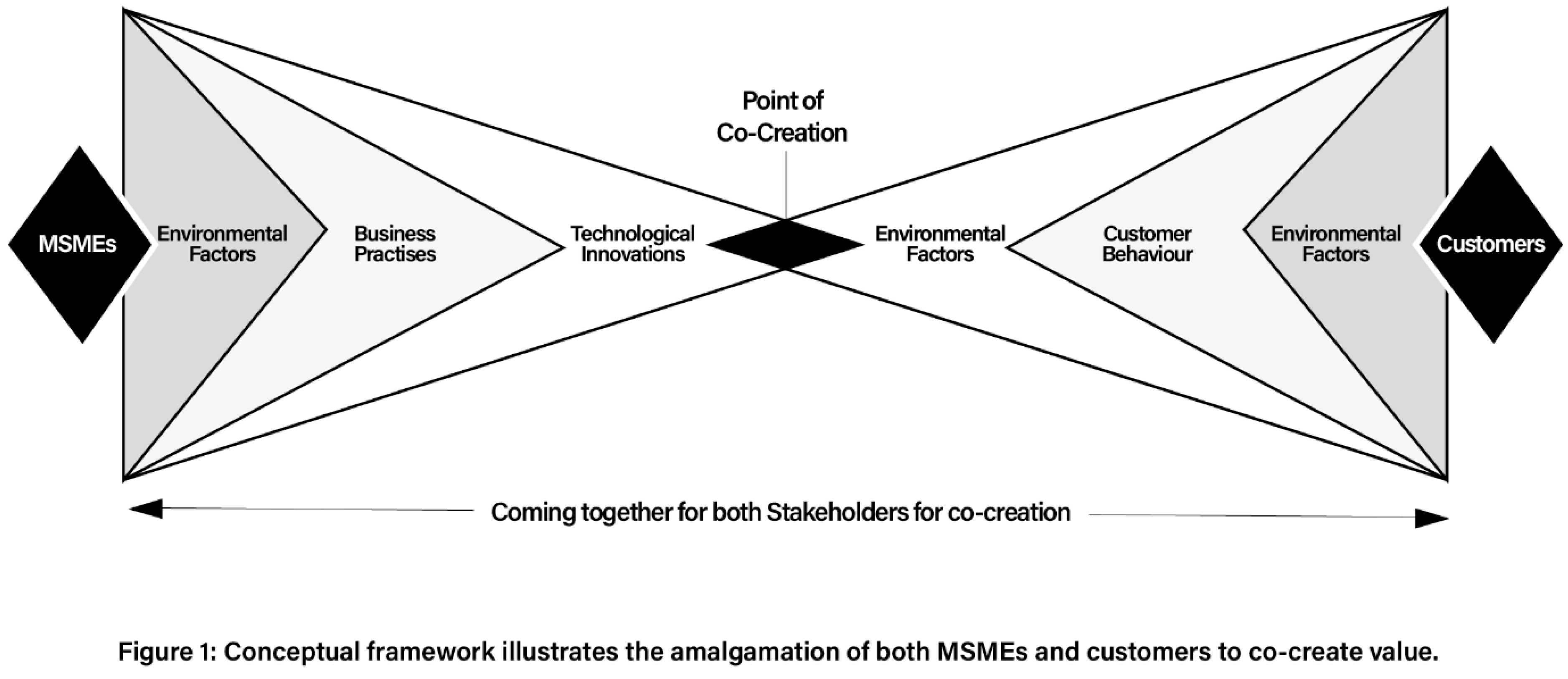

In pivoting and recognising the benefit of co creating values, there are practical implications for MSMES managers. Our conceptual framework in

Figure 1 illustrates the amalgamation of both MSMEs and customers to co-create value. The framework recognizes MSMEs and customers as key stakeholders and it posits that the closer both stakeholders come together, the more value they can co-create, this also suggests that co-creation may not be fully achieved if both stakeholders are not able to explore their potentials and challenges. This is especially so in relation to the inherent challenges that the pandemic has brough for both the businesses and the prospective customers.

From the MSMEs perspective, the framework recognises some possible challenges with their environmental factors, this aligns with the branding idea of country of origin and how it can affect the co-creation process (Conduit & Chen, 2017; Hidayanti et al, 2018). This is specifically so as MSMEs in emerging economies have been sandwiched between the pandemic and the economic challenges in the countries in which they operate (Gbadegeshin et al, 2021; Sun et al, 2020). While they try to be innovative and co create values, there are inherent challenges with the economic situation in their country, inadequate government policies to support business and often lack of funding and palliative support (Mogaji et al, 2021, Soetan et al, 2021). It is therefore important for managers to always acknowledge these challenges when exploring the possibilities of co-creation. Often this may be things outside their control, but they can’t ignore it, recognizing it and putting contingency measures in places can enhance their co creation process.

Importantly, the MSMEs need to recognise their business processes, especially as they have all being challenged by the pandemic (Hudecheck et al, 2020). This business practices involve sourcing for their materials in the wake of global challenges with logistics and supply, prospects of staff working from home, depending on the type of business, seeking additional funds for investment and innovation in the face of the pandemic (Nguyen & Mogaji, 2021). Managers are expected to adapt their business practices to align with the customers level of expectation. This also involves improving customer services to ensure the customers are being satisfied promptly which could involve having a chatbot to respond to queries, engaging with customers on social media and recognising the growing possibilities of artificial intelligence in automating task (Jafari-Sadeghi, 2020; Dwivedi et al, 2020).

This upgrade to business processes also involves specifically recognising the role of digital technology. Technology has become an integral part of business transformation and organisations are expected to adopt it to enhance their business operations (Abdulquadri et al, 2021). While this may vary across industry, it involves digital communication, marketing practice and having a deeper understanding about the customers. Automation of business as part of business transformation is important, especially as customers expectation and behavior are changing - customers wants prompt answer to their request, they want innovative products and service and wants engagement on a personalized level. MSMEs need to recognise these features and incorporate them into their business practices to improve the system It is however important to recognise that many of the MSMEs may not be able to afford this innovation, it is therefore advisable to start at a manageable rate, seek vendors and providers with cheaper offers, engage the services of freelancers or employ an intern who may have these skills but requires the right environment (El Tarabishy, 2020).

The customers role in the co-creation process is also being recognized. Though the MSMEs may not have much control over the situation of their customer, it is important to have a better understanding of the customers, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic and to know how best to engage and involve them in co-creation process (Gbadamosi, 2019; Hudecheck et al, 2020). Research for customer insight is important at this stage, to better understand how customer behavior has changed and evolved. Marketing practices before the pandemic may not be applicable in many of the situations now. Managers need to recognize the technology competence of the customers and integrate this in developing their own innovative ideas, it will not make a good business decision if the MSMEs develops a technology that customers don’t know how to use, not ready to use or will not use. Graduate integration of this technological innovations is essential for business practices and in pivoting them to create values.

The buying power of the customers may also have changed as the pandemic affected the customers and individuals around the world, customers may not have the disposable income to buy things and in some cases, they may be making more rational decisions (Habel et al, 2020; Widnyana, & Widyawati, 2020). It is therefore essential for managers to recognize this and shape their products (and services), pricing and promotional activities to recognize these possible changes. This recognition ensures that the customers are fully involved, and they can be carried along in the co creation process (Conduit & Chen, 2017).

Lastly, understanding the environmental factors of the customers is also important in exploring the co-creation possibilities (Babu et al, 2020; Zhang et al, 2019). The customers may be willing to get involved but this may not be possible due to the fundamental challenges with their environment which includes their country, economic situation, and financial capabilities. This is important for MSMEs who are considering expanding their business operations into other countries, especially for those in developed countries that are considering various emerging markets around the world. It is important to recognise that one size may not fit all, country specific innovative ideas are needed to invite the customers into the co-creation process, often it’s not about globalising the idea but localizing it to make it appealing to the customers (Lee et al, 2021).

Our conceptual framework has key factors that may affect the co-creating process. It is important to recognise that this is a generic conceptual framework and it may vary depending on the type of MSMES (product manufacturing or service provision), the type of economy (developed or emerging economy) and even the type of customers Ultimately the idea is to recognise the features and specifically how it appeals to their businesses and making effort that both stakeholders are brought together unto a common ground to enable the co creation process. A ground where environmental factors will align with business practices and the customers buying power and the technological innovations being presented by the company fully adopted by the customers.

7. Conclusions

This conceptual study highlights some of the challenges and opportunities for MSMEs in times of crisis such as COVID-19. Having provided a general review of trends in times of crises drawing upon a range of qualitative accounts, the overarching message is in highlighting a direction of travel for MSMEs. This is with a view to galvanising the bottom-line of MSMEs, not just after the crisis, but more importantly at this particular point in time. There are obvious implications for “pivoting,” in order to cushion the impact of the pandemic on efforts to capacitate MSMEs in leveraging value co-creation with the consumers.

While we acknowledge that the devastating effects of COVID-19 permeates virtually all aspects of life across geographic boundaries, there are adjustment mechanisms that have been thus far successfully managed. As the lockdown is eased across many parts of the world, attention is now being focused on how to navigate the ‘now normal’ business environment towards achieving sustainable development empathetically. Ultimately, this study highlights the interaction between opportunity and necessity in navigating the crisis. While several opportunities have arisen because of the crisis e.g., pivoting into production of facemasks/shields as well as hand sanitisers (see for example, Hinson et al., 2020), there have also been necessity driven pivoting. For example, numerous professional consultancies have been started mainly by furloughed employees. In summing up, therefore, we posit that for a sustainable global economy, the roles and activities of MSMEs in co-creating value with their customers would be more relevant than ever before, but the role of technology in ensuring economic recovery and sustainability would remain fluid in the short, medium and long term. This is where the pivoting of MSMEs comes into the discourse.

References

- Abdulquadri, A., Mogaji, E., Kieu, T. A., & Nguyen, N. P. (2021). Digital transformation in financial services provision: a Nigerian perspective to the adoption of chatbot. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy. 15 (2), 258-281. [CrossRef]

- Adenle, A. A., Manning, L., & Azadi, H. (2017). Agribusiness innovation: A pathway to sustainable economic growth in Africa. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 59, 88-104. [CrossRef]

- Adeyanju, S., Ajilore, O., Ogunlalu, O., & Onatunji, A. (2022). Innovating in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Studies from Nigerian Universities. STAR Scholar Book Series, 104-120.

- Adom, K., Chiri, N., Quaye, D., & Awuah-Werekoh, K. (2018). An Assessment of Entrepreneurial Disposition and Culture in Sub-Saharan Africa: Some Lessons from Ghana. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 23(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Ameye, H., & De Weerdt, J. (2020). Child health across the rural–urban spectrum. World Development, 130, 104950. [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2004). Does entrepreneurship capital matter? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(5), 419-430. [CrossRef]

- Babu, M. M., Dey, B. L., Rahman, M., Roy, S. K., Alwi, S. F. S., & Kamal, M. M. (2020). Value co-creation through social innovation: A study of sustainable strategic alliance in telecommunication and financial services sectors in Bangladesh. Industrial Marketing Management, 89, 13-27. [CrossRef]

- Baker, S. R., Farrokhnia, R. A., Meyer, S., Pagel, M., & Yannelis, C. (2020). How does household spending respond to an epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID19 pandemic (No. w26949). National Bureau of Economic Research. [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, CL, El Tarabishy, A., DeNoble, A., Puerto, S., & Parente, R. (2020) ICSB Special Certificate Program: Teaching the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – May 7-9, 2020. https://icsb.org/icsbsdgs/.

- Carpentier, CL, Landveld, R., and Shahiar, N. (2019) Role of MSMEs and Entrepreneurship in achieving the SDGs. UNCTAD. ICSB Annual Global MSME Report June 27. https://icsb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/REPORT-2019.pdf.

- Chang, R., & Velasco, A. (2020). Economic Policy Incentives to Preserve Lives and Livelihoods (No. w27020). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., & Weber, M. (2020). Labor Markets During the COVID19 Crisis: A Preliminary View (No. w27017). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Conduit, J., & Chen, T. (2017). Transcending and bridging co-creation and engagement: conceptual and empirical insights. Journal of Service Theory and Practice. 27(4), 714-720. [CrossRef]

- Das, J. (2020). Zen and the art of experiments: A note on preventive healthcare and the 2019 Nobel Prize in economics. World Development, 127, 104808. [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. (2015). Entrepreneurial opportunities and the entrepreneurship nexus: A re-conceptualization. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(5), 674–695. [CrossRef]

- Devece, C., Peris-Ortiz, M., & Rueda-Armengot, C. (2016). Entrepreneurship during economic crisis: Success factors and paths to failure. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5366-5370. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, D. L., Coombs, C., Constantiou, I., Duan, Y., Edwards, J. S., Gupta, B.,Lal, B., Misra, S., Prashant, P., Raman, R., Rana, N., Sharma, S. K., & Upadhyay, N. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. International Journal of Information Management, 102211. [CrossRef]

- El Tarabishy, A. (2020) Helping Small Businesses Change the World. Medium.com, 9 May. https://medium.com/@aymanelt/helping-small-businesses-change-the-world-7c04d10862e7.

- Gbadamosi, A. (2015), ‘Exploring the Growing Link of Ethnic Entrepreneurship, Markets, and Pentecostalism in London (UK): An Empirical study’, Society and Business Review, vol. 10, No. 2, pp.150-169. [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, A. (2019a), ‘Women Entrepreneurship, Religiosity, and Value-co-creation with Ethnic Consumers: Revisiting the Paradox’, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 27 (4) 303-316. [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, A. (2019b), ‘Marketing: A Paradigm Shift’, in Gbadamosi, A. (Ed) Contemporary Issues in Marketing, London: SAGE, pp. 3-31.

- Gbadegeshin, S. A., Olaleye, S. A., Ukpabi, D. C., Omokaro, B., Ugwuja, A. A., ... & Adetoyinbo, A. (2021). A study of online social support as a coping strategy. Technology and Women’s Empowerment, 200- 217.Gibb, A. A. (1996). Entrepreneurship and small business management: can we afford to neglect them in the twenty-first century business school? British Journal of Management, 7(4), 309-321.

- Grant, K. W. (Forbes, May 16, 2020) The Future of Music Streaming: How COVID19 Has Amplified Emerging Forms of Music Consumption. Online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinwestcottgrant/2020/05/16/the-future-of-music-streaming-how-Covid19-has-amplified-emerging-forms-of-music-consumption/.

- Grönroos, C. (2008), “Service logic revisited: who creates value? And who co-creates?” European Business Review, 20(4), 298-314.

- Habel, J., Jarotschkin, V., Schmitz, B., Eggert, A., & Plötner, O. (2020). Industrial buying during the coronavirus pandemic: A cross-cultural study. Industrial Marketing Management, 88, 195-205. [CrossRef]

- Hidayanti, I., Herman, L. E., & Farida, N. (2018). Engaging customers through social media to improve industrial product development: the role of customer co-creation value. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 17(1), 17-28. [CrossRef]

- Hinson, R. E., Hein, W., Tettey, L. N., Nartey, B. A., Harant, A., Struck, N. S., & Fobil, J. N. (2021). Critical prerequisites for Covid-19 vaccine acceleration: A developing economy perspective. Journal of Public Affairs, e2723. [CrossRef]

- Hinson, R. E., Donkor, P. O., & Madichie, N. (2020) COVID-19 and universities’ commercial appetites. University World News, 18 June 2020. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200614200443526.

- Hudecheck, M., Sirén, C., Grichnik, D., & Wincent, J. (2020). How companies can respond to the Coronavirus. MIT Sloan Management Review, 17 April. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/monitoring-the-Covid19-crisis-from-space/.

- ICSB Annual Global MSME Report June 27, 2018. https://icsb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/REPORT-ICSB-2018.pdf.

- Igwe, P. A., Madichie, N. O., & Newbery, R. (2019). Determinants of livelihood choices and artisanal entrepreneurship in Nigeria. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 25(4), 674-697. [CrossRef]

- Jafari-Sadeghi, V. (2020). The motivational factors of business venturing: Opportunity versus necessity? A gendered perspective on European countries. Journal of Business Research, 113(C), 279-289. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M., Afzal, M. S., Khan, A., & Ahmed, H. (2020). COVID19 economic cost; impact on forcibly displaced people. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, (May-June), 35:101661. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M., Nilsson, T., & Pichler, S. (2014). The impact of the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic on economic performance in Sweden: An investigation into the consequences of an extraordinary mortality shock. Journal of Health Economics, 36, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M., & Partanen, J. (2016). Co-creating value from knowledge-intensive business services in manufacturing firms: The moderating role of relationship learning in supplier–customer interactions. Journal of Business Research, 69(7), 2498-2506. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Kim, H., & Choi, S. (2021). Corporate Glocalization Strategy of Nongshim in America: The “Pendulum Theory” of Globalized Localization. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(4), 205. [CrossRef]

- Lounsbury, M., Cornelissen, J., Granqvist, N., & Grodal, S. (2019). Culture, innovation and entrepreneurship. Innovation, 21(1), 1-12.

- Li-Ying, J., & Nell, P. (2020). Navigating opportunities for innovation and entrepreneurship under COVID-19. California Management Review, 63(1), 1-7.

- Madichie, N. O. (2020) Entrepreneurship & Youth Employment in Africa: Barbershop Narratives. Paper presented at the 2020 Virtual Conference of the International Council for Small Business (ICSB), 25 July.

- Madichie, N. O. (2009). Breaking the glass ceiling in Nigeria: A review of women’s entrepreneurship. Journal of African Business, 10(1), 51-66. [CrossRef]

- Madichie, N. O., & Agu, A. G. (2023). The Role of Universities in Scaling up Informal Entrepreneurship. Industry and Higher Education, 37(1), 94-109. [CrossRef]

- Marton, F. (1988). Phenomenography: A research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. Qualitative research in education: Focus and methods, 21, 143-161.

- McAleer, M. (2020). Prevention Is Better Than the Cure: Risk Management of COVID19. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(3), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E., & Nguyen, N. P. (2021). Can we brand a pandemic? Should we? The case for corona virus, COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(2), e2546. [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E., Hinson, R. E., Nwoba, A. C., & Nguyen, N. P. (2021). Corporate social responsibility for women’s empowerment: a study on Nigerian banks. International Journal of Bank Marketing. 39(4), 516-540.

- Morgan, T., Anokhin, S., Ofstein, L., & Friske, W. (2020). SME response to major exogenous shocks: The bright and dark sides of business model pivoting. International Small Business Journal, 0266242620936590. [CrossRef]

- Muhanda, R., Were, V., Oyugi, H., & Kaseje, D. (2020). Evaluation of Implementation Level of Community Health Strategy and Its Influence on Uptake of Skilled Delivery in Lurambi Sub County-Kenya. EA Health Research Journal, 4(1), 65-72. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.N., Mogaji, E. (2021). Emerging Economies in Fashion Global Value Chain: Brand Positioning and Managerial Implications. In F. Brooksworth, E. Mogaji, & G. Bosah (Eds.), Fashion Marketing in Emerging Economies – Strategies, Tools and Insights for Fashion Brands. Cham: Springer.

- Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir, A., Iosifidis, C, Agha, M., & Agha, R. (2020). The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus and COVID19 Pandemic: A Review. International Journal of Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, C. (2015). Are SMEs still profitable in an economic crisis? Qualitative research on Romanian entrepreneurship and crisis management. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Economic Sciences. Series V, 8(2), 217-232.

- Pilo, M. (2019). Dynamics of Agricultural Productivity and Technical Efficiency in Togo: The Role of Technological Change. African Development Review, 31(4), 462-475. [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K. and Ramaswamy, V. (2004), “Co-creating unique value with customers”, Strategy & Leadership, 32(3), 4-9. [CrossRef]

- Rao, H. R., Vemprala, N., Akello, P., & Valecha, R. (2020). Retweets of officials’ alarming vs reassuring messages during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for crisis management. International Journal of Information Management, 102187. [CrossRef]

- Rapaccini, M., Saccani, N., Kowalkowski, C., Paiola, M., & Adrodegari, F. (2020). Navigating disruptive crises through service-led growth: The impact of COVID-19 on Italian manufacturing firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 88, 225-237. [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V., & Ferreira, J. J. (2017). Future research directions for cultural entrepreneurship and regional development. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 21(3), 163-169.

- Raward, C. (2004). Leading innovation and entrepreneurship in the Australian red meat industry. Innovation, 6(3), 430-443. [CrossRef]

- Reid, A. (Entrepreneur, 10 May 2020) Best Practices for Marketing During and After COVID19. Retrieved from: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/349535.

- Reid, A. (Entrepreneur, 10 May 2020) Best Practices for Marketing During and After COVID19. Retrieved from: https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/349535.

- Russell, F. (Gartner, April 17, 2020) Adapt Customer Listening to Improve CX During COVID. https://blogs.gartner.com/frances-russell/2020/04/17/adapt-customer-listening-to-improve-cx-during-covid/.

- Saha, V., Mani, V. and Goyal, P. (2020), Emerging trends in the literature of value co-creation: a bibliometric analysis, Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(3), 981-1002. [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, M., & Muffatto, M. (2018). High-tech entrepreneurial ecosystems: using a complex adaptive systems framework. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 22(6), 615-634. [CrossRef]

- Sein, M. K. (2020). The Serendipitous Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rare Opportunity for Research and Practice. International Journal of Information Management, 102164. [CrossRef]

- Skutsch, M., & Turnhout, E. (2020). REDD+: If communities are the solution, what is the problem? World Development, 130, 104942. [CrossRef]

- Soetan, T. O., Mogaji, E., & Nguyen, N. P. (2021). Financial services experience and consumption in Nigeria. Journal of Services Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Statista (2020a), Global Digital Population as of April, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/ (Accessed, 9 May 2020).

- Statista (2020b), ‘Global Number of Internal users 2005-2019’. https://www.statista.com/statistics/273018/number-of-internet-users-worldwide/ Accessed, 9 May 2020).

- Statista (2021), ‘Global Number of Internal users 2005-2019’ www.statista.com/statistics/273018/number-of-internet-users-worldwide/ (Accessed, 6 June, 2022).

- Statista (2022), ‘Worldwide digital Population as of April, 2022, www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/ (Accessed, 6 June, 2022).

- Valinsky, J. (2020). Business is booming for these 14 companies during the coronavirus pandemic. CNN Business, 7 May. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/07/business/companies-thriving-coronavirus-pandemic/index.html.

- Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R.F. (2004), “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing”, Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L. and Lusch, R.F. (2008), “Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- WHO (2023), ‘WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID19) Dashboard’. https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed 30th October, 2023).

- Widnyana, I. W., & Widyawati, S. R. (2020). Supply of Consumer Goods, Per Capita Consumption due to Covid-19 Pandemic. Economics Development Analysis Journal, 9(4), 458-467. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Bai, Y., & Li, S. (2020). Examining the Antecedents of Brand Engagement of Tourists Based on the Theory of Value Co-Creation. Sustainability, 12(5), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. (1988). Consumer perception of price, quality and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, M., Luo, N., Wang, Y., & Niu, T. (2019). Understanding the formation mechanism of high-quality knowledge in social question and answer communities: A knowledge co-creation perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 48, 72-84. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).