1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had major repercussions on the work of the healthcare staff who were mobilized to react to this health emergency without precedent in the 21st century. Healthcare staff had to work in a context where knowledge about the virus and its transmission was constantly evolving, where protective equipment was not always available and procedures changed with the course of the pandemic. In addition, isolation rules that were in effect for COVID-19 infected healthcare workers or those in contact with a COVID-19 case, had an impact on the number of available workers. Even outside the context of an epidemic, healthcare personnel are among those most affected by problems relating to mental health, burnout and staff turnover [1–5]. During epidemics and pandemics like COVID-19, there is a greater burden of mental health symptoms and problems [6,7], especially for healthcare workers [8–11].

In the province of Quebec, Canada, the vast majority of healthcare and social services institutions (HCI) are public and are under the authority of Quebec’s health and social services department. This department shares its responsibilities with 34 public institutions, whose primary role is to provide the public with health and social services [12]. In 2023, the total number of people working in the health and social services network was over 300,000 [13]. This network has undergone numerous transformations over the past 20 years. The most recent one, dating to 2015, involved the passing under closure of Bill 10 under the leadership of Minister Gaétan Barrette. It has been described by some media as the worst reform ever of Quebec’s health and social services network: “Exhausted professionals, increasingly difficult access to care, ultra-centralized management: the effects of “Hurricane Barrette’ are still being felt five years later, and they have weakened the healthcare network” [Translation] [14]. This major restructuring centralized administrative services and decision-making authority by reducing the number of institutions in the network from 182 to 34. These institutions also became known as “integrated centres” or “integrated university health and social services centres”. More than 1,300 managers lost their jobs in the course of this exercise [14].

It was therefore in a context still strongly marked by these major transformations and challenging working conditions in the health and social services network that the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in Quebec in March 2020. In addition to issues like high demands and staffing shortage [1,3,5], healthcare personnel faced numerous stressors associated specifically with the pandemic. These included concerns relating to the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) or to its protective efficacy (e.g. medical masks versus N95 masks), involuntary deployment, assignment to new teams and tasks outside one’s skill set, increased work-family conflict related to school and daycare closures, and the experience of moral dilemmas when caring for infected patients while risking one’s own health or that of loved ones or when having to compromise care due to resources constraints [6,7,15–19]. Balancing work and personal life was particularly difficult with the additional significant workload caused by the pandemic and was one of the factors mainly associated with psychological distress of the healthcare workers in Quebec during the COVID-19 pandemic [15]. Not only were there major absenteeism issues, but the ratio of insured hours of lost time to the total number of hours worked by personnel rose by 29% on average within HCI between 2014-2015 and 2019-2020 [12]. Mental health problems seem to have generated the highest costs over the past several years, in addition to accounting for the highest number of lost work hours in Quebec’s health and social services network [20,21].

In a recent literature review and meta-analysis, Duchaine et al. [22] demonstrated that workers exposed to psychosocial risks in the workplace had a 23% to 76% greater risk of being absent from work due to a physician-diagnosed mental disorder than did workers not exposed to such risks. A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analyses over a period of 20 years showed that exposure to various work-related psychosocial risks, such as high psychological demands, lack of decisional autonomy, low support from colleagues and supervisors, low recognition at work, and exposure to violence or threats, increases the likelihood of developing or suffering from depressive disorders and burnout, and having suicidal thoughts [23].

Primary preventive organizational interventions can be effective in reducing workers’ exposure to work-related psychosocial risks such as excessive workload, low job control and poor social support. As such, primary-level interventions, when adequately supported and implemented, can help prevent mental health problems in the workplace [24–27]. In their meta-analysis, Panagioti et al. [28]demonstrated that interventions targeting organizational factors were more effective than individual-level interventions when it comes to protecting physicians against burnout. Other authors have estimated that 44% of employee turnover in hospitals could be prevented by improving the psychosocial work environment [29]. A recent systematic review of 2000 to 2021 scientific literature identified some organizational measures for protecting the mental health of healthcare workers during epidemics and pandemics, based on seven medium-quality studies. These organizational measures include staffing adjustments, work shift arrangements, enhanced infection prevention and control, recognition of workers’ efforts, and psychological and/or logistic support during lockdowns, but the authors confidence in the effectiveness of reviewed interventions is low to very low [30].

Despite the vast extent of studies highlighting the negative effects of being exposed to psychosocial risk on mental health [22,23,31,32], there still is a scarcity of knowledge on strategies that are implemented by organizations during a pandemic to reduce these risks. As HCI around the world were under great pressure during the pandemic, it was difficult to know how prevention was being carried out on the ground, as access for researchers was limited and healthcare workers were overworked. Literature on organizational-level interventions shows how crucial it is to evaluate the process as well as the effects, but a number of methodological shortcomings remain, not least because the context is not systematically studied [27]. Indeed, Aust's systematic review highlights the fact that organizational-level interventions can differ in their complexity regarding implementation, which has an impact on its effects [27]. By calling on key interlocutors who have a good knowledge of which organizational measures were implemented during the pandemic, such as HR advisors, it is possible to have an interesting proxy on implementation and perceived effectiveness.

The purpose of this study is to provide an overview of the measures introduced or maintained by the institutions of the Quebec health and social services network during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to protect the mental health of their personnel. We also sought to document the perceived effectiveness of the measures by HR people responsible, at least in part, for implementing them within their organization.

This study was part of a larger project aimed at developing knowledge on mental health protection strategies for healthcare personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a view to designing a workplace support tool. The two other studies from the larger project are reported in other articles [references omitted for blinded peer-review].

Theoretical framework

Work-related psychosocial risks are factors related to work organization, employment conditions, management practices and social relations at work, that increase the likelihood of an adverse effect on the physical and mental health of persons who are exposed to them [33]. This definition is based on the two recognized theoretical models of job stress, namely, the job demand-control model of Karasek and Theorell [34] and the effort-reward imbalance model of Siegrist [35], which have gained international renown. Over time, other theoretical models have been proposed, such as the Organizational justice model [36] and the Job Demands – Resources model [37–40]. Psychosocial risk factors increase the likelihood of developing mental health problems in exposed workers, suggesting that preventive measures are needed to mitigate their effects in order to protect worker’s mental health. Some studies have led to the proposal of concrete organizational measures that workplaces can implement to act in primary prevention of what are considered modifiable psychosocial risks, which are generally measures targeting workload, recognition at work, social support from colleagues and supervisors, decisional autonomy, communication and information and balancing work and personal life [33,41–44]. The implementation and success of such organizational measures aimed at protecting mental health in the workplace depends, among other things, on the importance and priority given by the organization to psychological health and safety in the workplace, a concept called psychosocial safety climate [45]. This concept refers to the importance and priority that organizations attach to psychological health and safety in the workplace. The psychosocial work safety climate is considered upstream of the aforementioned psychosocial risks [46–48]. Recent work shows that organizations with a strong psychosocial safety climate have better mental health outcomes, not least because the psychosocial safety climate acts upstream of psychosocial risks at work [49].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We targeted Quebec’s 34 HCI that make up the Quebec health and social services network. Each of these institutions has a human resources management team responsible for implementing prevention measures to reduce psychosocial risk factors in the workplace. The size of each team varies based on the number of staff members in the institution to which it belongs [50].

An online questionnaire was administered to HR personnel. When we first contacted each team, we specified that we hoped to enlist the participation of key informants from each institution who were familiar with the measures that had been implemented in their institution to protect workers’ mental health since the start of the pandemic.

There were 31 participating institutions, for a response rate of 91.2%. A total of 223 HR advisors answered the questionnaire, with at least one respondent per institution. The number of respondents per institution ranged between one and 24.

2.2. Measures

The questionnaire was developed by our research team and reviewed for clarity and relevance by an advisory committee, set up at the very beginning of the research and made up of various local stakeholder representatives, including labour unions, employer and department representatives, professional orders in the health and social services network, and user representatives. The questionnaire first assessed the psychosocial safety climate using the validated PSC-4 instrument [45]. The PSC-4 was measured using four questions (e.g. Senior management shows support for the prevention of psychological health problems through involvement and commitment), according to a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The instrument was translate in french language, but this version is not validated yet. The PSC-4 score ranges from 4 to 20 points, with higher scores indicating better psychosocial safety climate.

HR advisors were then asked about the presence of organizational measures in their institution through a series of close-ended questions. For each item, respondents should first indicate if the measure was in place, not in place or if they didn't know. Then, for measure in place, they had to tell if from their standpoint, the measures are efficacious in protecting healthcare workers’ mental health. Of these measures, eight were designed to reduce employees’ workload; seven to increase their recognition at work; six to improve the support of colleagues and supervisors; three to increase decisional autonomy; four to promote the communication and sharing of information; and five to target better work/life-balance. These measures were selected from work on recognized organizational measures for reducing psychosocial risk factors in the workplace as cited in the theoretical framework. Finally, eight COVID-19 measures were included in the questionnaire derived from infection prevention and control (IPC) initiatives in HCI recommended by Quebec public health authorities during the COVID-19 pandemic [51]. Some of these measures touch upon decisional autonomy (e.g. choosing to work in a red zone), others relate to work organization or management practices that may influence the perceived safety of work (e.g. IPC training, PPE access, on-site COVID-19 screening).

The questionnaire also included open-ended questions on measures that HR advisors had deemed successful and those that they had deemed less successful in reducing psychosocial risk factors and protecting mental health. The fact that these questions were open-ended enabled the respondents to explain their answers.

The survey was deployed online through a community of practice in HR management, bringing together advisors from the 34 institutions in Quebec’s health and social services network. The data were collected between May 14 and June 4, 2021. Two reminders were sent by email on May 21 and May 31, 2021.

2.3. Analyses

Answers to open-ended questions were subjected to deductive and inductive thematic content analysis [52]. The themes were identified using the aforementioned theoretical frameworks for psychosocial risk factors in the workplace and the Tool for Identifying Psychosocial Risk Factors in the Workplace adapted to the work context in the health and social services network [53,56]. Other themes could also emerge during the analysis.

For the close-ended questions, we calculated the proportion of the total number of respondents who reported that a particular measure had or had not been implemented in their institution. Among those who reported that the measure had been implemented, we calculated the proportion of respondents who deemed that the measure was efficacious, fairly efficacious or not very efficacious in protecting workers’ mental health, based on the respondent’s subjective assessment. We also calculated the PSC-4 score for each institution, as perceived by HR staff, using the average scores of the respondents in each institution. Since the goal was to obtain an overview of the measures implemented across Quebec’s health and social services network, rather than a portrait of the measures per institution or establishment, we present results based on the overall number of respondents.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the organizational measures implemented

Respondents had been asked to indicate if listed measures in the close-ended questions had been implemented and their perceived efficacy of implemented measures to protect the mental health of the healthcare staff, based on their personal assessment as key informants. The results are presented in

Table 1.

The five measures reported to have been implemented according to the largest proportion of respondents are those that were intended to foster civility and respect (95% of respondents), resolve interpersonal conflicts (89% of respondents), promote the use of appropriate means of communication (e.g. message boards, meetings, emails, videoconferences, newsletters) (89%), offer flexible hours, shorter work weeks or part-time positions (84%) and ensure sufficient access to PPE (e.g. medical masks, respiratory protection devices (RPDs), visors) (83%).

The five measures least reported to have been implemented were those to provide COVID-19 staff with meals (occasionally or always) (26%), give them access to lounge areas (31%), increase manager-to-staff ratios (32%), provide training in communications (37%) and offer on-site daycare facilities or daycare service agreements (42%).

As for the perceived efficacy of the measures, those that were deemed efficacious in mental health protection by the vast majority of respondents declaring that a particular measure had been implemented, included four specific COVID-19 measures: COVID-19 screening tests available in the workplace (deemed efficacious by 84% of respondents who reported that this measure was in place); sufficient access to PPE (e.g. medical masks, RPDs, visors) (deemed efficacious by 79% of respondents who reported that this measure was in place); financial compensation measures during isolation/quarantine and training in PPE measures, respectively deemed efficacious by 76% and 74% of respondents who reported that these measures were in place. The fifth measure reported to be efficacious by the vast majority of respondents was facilitation of telework (deemed efficacious by 62% of respondents who reported that it was in place).

The measures considered to be not very efficacious by the vast majority of respondents were those to provide access to lounge areas (considered not very efficacious by 43% of respondents who reported that the measure was present); offer corporate rebate programs (43%); hire new staff or increase staff-to-patient ratios (38%); limit overtime (38%) and reduce mandatory overtime (37%). It is interesting to note that the measures likely to have a direct impact on the workload of healthcare workers, i.e. those targeting staffing and overtime work, were perceived as being not very efficacious by HR staff. This may be because the measures were applied in a number of different ways, for a limited time period or intermittently, or because they were offered to only a small number of healthcare workers. Since these paradoxical results are based on the perception of the advisors surveyed rather than on that of the staff who cared for patients, they must be interpreted with caution. They highlight the relevance of using a participatory approach to identify risks and elaborate solutions, so that the needs on the ground are aligned with the solutions proposed by employers.

It is also interesting to note that a fairly large proportion of the HR staff said that they were not aware of the existence of certain measures in their institutions. Regarding COVID-19 measures, 42% of respondents did not know that workers could choose whether or not they wanted to work in red zones, 38% did not know if meals were offered and 37% did not know if accommodations were provided to infected or isolated staff assigned to COVID-19 wards or if financial compensation measures were in place for isolated or quarantined workers.

Successful measures reported in the open-ended questions

The measures reported by the respondents to be successful in protecting mental health were grouped under nine themes (indicated in bold below). The theme “individual measures” is a new theme that emerged during the analysis.

The measures most frequently reported to be successful by the respondents were in the “individual measures” category. They included the enhancement of the worker assistance program (through the addition of psychotherapy sessions, for example); the implementation of a psychological helpline; the development of stress management, relaxation and meditation toolkits and activities; and the implementation of a selfcare information platform.

The second category of successful measures reported by the respondents consisted of measures to support colleagues. The two most frequently reported measures in this category were the creation of special staff psychological health teams and peer support groups. Some respondents also mentioned providing training to detect psychological warning signs among colleagues as being successful.

Measures for enhancing the support of supervisors was the third category of measures deemed to be successful. The measures in this category were designed to enable managers to be more present on the ground with their teams (e.g. by reviewing their roles and responsibilities and alleviating them from some of these). In addition, the measures were intended to train, accompany, and coach managers and senior managers to give priority to a benevolent management approach that was sensitive to the psychological distress of employees and managers (workshops webinars, management group discussions, etc.).

Information and communication measures was the fourth category of measures reported to have been successful. Most of the respondents said that their institution had increased the amount of information available on psychological health in the workplace and the pandemic situation as well as the number of means used to communicate with employees (e.g. websites, intranet, capsules, webinars, team meetings, newsletters, emails, collaboration platforms). It should be noted that one respondent commented that the president and executive director of their institution had held webinars with all employees in order to explain the labour shortage situation and the measures that had been implemented to offset the impact of the increased workload on staff members’ health.

Measures for work/life-balance was the next category of measures that were reported to have been successful, with the most frequently reported being the implementation of telework. However, some respondents mentioned other measures such as free daycare services and flexible hours aimed at facilitating work/life-balance.

The successful measures reported in the recognition at work category consisted mainly of general recognition programs for the entire staff of an institution, along with corporate rebates, shows and prize draws or measures to highlight the exceptional engagement of certain teams.

Few measures targeting workload were reported by HR. These measures consisted in developing and deploying ergonomic information systems and streamlined procedures to alleviate the administrative burden on employees; creating a workload committee to find solutions for reducing workload; and cancelling committee and working group meetings requiring the participation of numerous middle managers.

Only one measure was reported to act successfully on decisional autonomy. It involved the introduction of participatory management of the recall list to ensure the replacement of absent employees. Lastly, some respondents mentioned measures to globally assess or manage psychosocial risk factors in the workplace, such as a survey distributed to staff members in order to gauge work-related psychological risks, an initiative to set up a psychological health prevention program and, lastly, an action plan implemented in certain teams that were more vulnerable or were experiencing psychological distress.

The respondents explained that all these measures were successful because, in their opinion, the actions targeted staff members’ needs, particularly through a range of measures that enabled them to express their views and feel like they were being heard, and to gain rapid access to support. The respondents also said that the measures to enlist the participation of all hierarchical levels and provide leeway, along with authentic, sincere and honest recognition, contributed to their success.

Measures reported as less successful in the open-ended questions

The respondents were also asked to talk about the measures that were less successful. Several said that helplines or psychological support by in-house teams were used to only a limited extent. According to the respondents, these measures did not work very well, mainly because the respondents were embarrassed, afraid of being judged or reticent to confide in their colleagues due to a lack of trust.

Measures that required a greater contribution or more participation on the part of managers were also reported to be less well adapted to managers’ workload. In fact, some respondents reported that managers were often overwhelmed and were unable to, for example, raise awareness within their teams or to identify people at risk of distress. Therefore, according to some respondents, employee recognition campaigns with strong messages on the value of staff or positive thoughts intended to mobilize employees did not work very well. In their opinion, messages of this type were seen as lacking in authenticity and many people made cynical comments about them. In fact, the contrast between the positive messages being put out and the lack of actions being taken in the field to reduce workload had a demobilizing effect. Lastly, one of the reasons reported by a few respondents for the failure of certain measures was the lack of clear direction on the part of senior management who had requested measures to act on employees’ mental health, but did not officially support or promote these measures.

Psychosocial safety climate

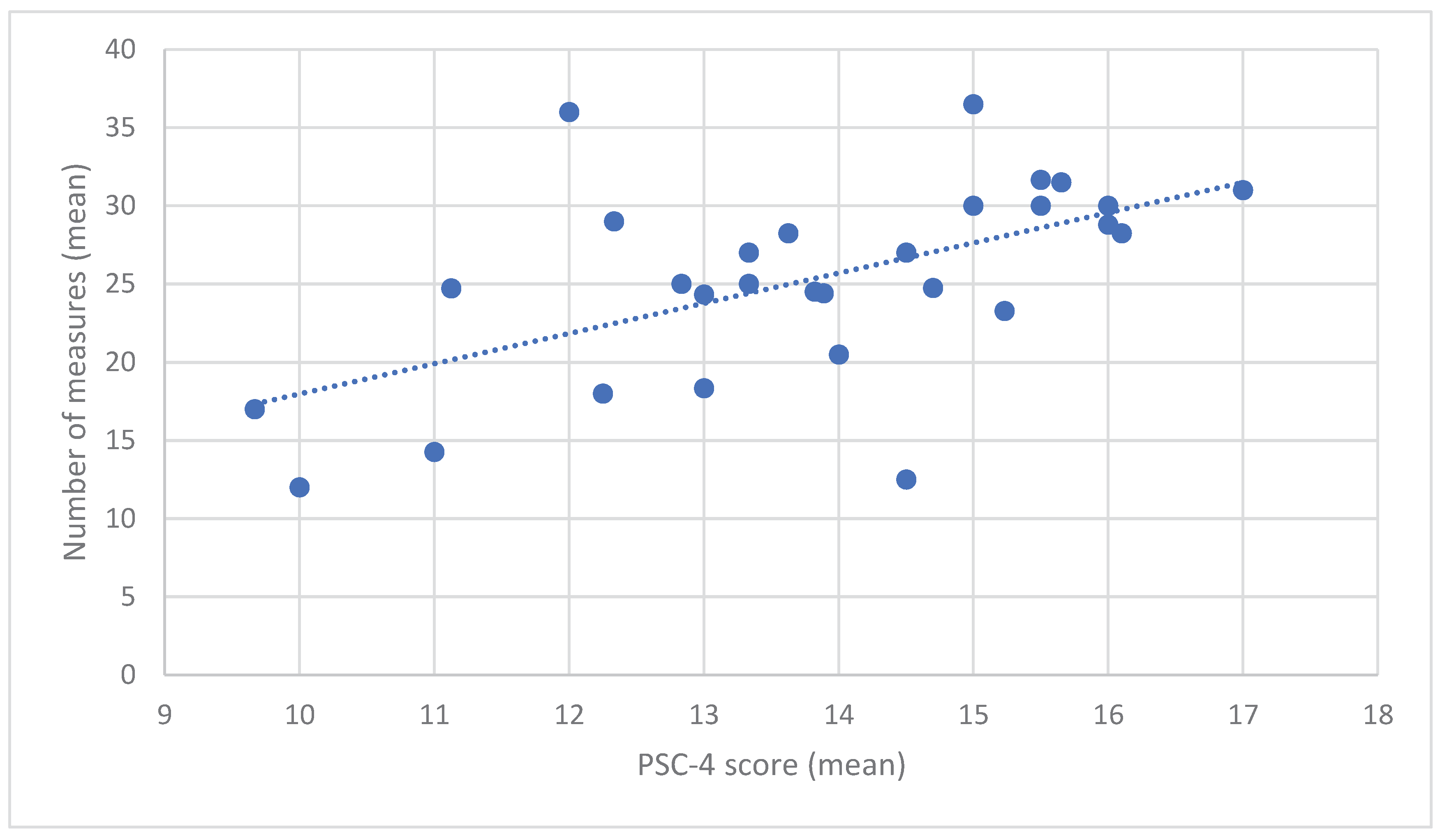

The score for the psychosocial safety climate (PSC-4) indicator varied between approximately 10 and 17 points depending on the institution, with the majority of institutions obtaining a score of at least 12 points (on a scale of 4 to 20 points). As can be seen in

Figure 1, an exploratory analysis showed that the higher the score was, the greater was the number of measures that were reported to have been implemented (Pearson correlation: 0.57; n = 29 institutions with complete data for the PSC-4 and number of measures).

Some measures perceived by HR advisors as more successful and some comments made in the open-ended questions reflected different dimensions of the psychosocial safety climate, such as management’s commitment to psychological health:

“We placed the focus on manager training and equipped employees with the various tools available. This was good, but it was too little too late. Within two weeks, we’ll be starting to apply the “Healthy Enterprise” program. We strongly feel that we are supported by management. We’ll see how their commitment translates into action.” [Translation]

The successful measure mentioned below reflected another dimension of the psychosocial safety climate, namely, the priority assigned to psychological health versus productivity objectives:

“Full recognition of labour shortages and temporary service closures instead of wearing out staff through mandatory overtime.” [Translation]

The dimension pertaining to communication about psychological health was reflected by, for example, the following measure:

“Keeping managers and workers involved, listening to and addressing their concerns, disseminating key information and developing a common vision of where we are and where we’re going! A forum for dialogue to keep people informed and promote exchanges, so that they can express their concerns.” [Translation]

Lastly, the dimension pertaining to the consultation and participation of workplace stakeholders was reflected by the following comment, among others:

“Holding meetings at the local level allow red flags to be raised for managers and to ensure that risks are assessed.” [Translation]

4. Discussion

This study provided an overview of the measures reported by HR advisors to have been implemented by HCI in Quebec during the COVID-19 pandemic. These organizational measures aimed to reduce workplace psychosocial risks and protect healthcare worker mental health. Since there was a limited access to HCI during the crisis, understanding how psychosocial risks were prevented is highly relevant given their impact on mental health, absenteeism, and turnover. Although most respondents highlighted mainly individual measures as having been successful, they also reported that several organizational measures had been implemented, with varying perceived efficacy from the point of view of the HR staff. The wide variety of reported measures across the health and social services network could be related to the fact that, in 2017, Quebec’s health and social services department had initiated a shift toward mental health prevention in the workplace. This approach had been incorporated into a national action plan to prevent workplace hazards and promote comprehensive health for the period 2019-2023 [50]. This plan provided for the training of HR professionals and for the implementation of preventive organizational interventions in institutions throughout the network. This change in preventive culture may have had a positive impact on the number of organizational measures put in place during the pandemic. Organizational measures usually allow for primary prevention intervention. In other words, they are designed to reduce exposure to psychosocial risks in the workplace by modifying the work environment and thereby reducing risks to mental health at the source. Primary prevention strategies are usually those that must be given priority in a public health approach. A systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that organizational interventions are more effective than individual measures in preventing physician burnout [28]. Others have suggested that combining organizational and individual interventions is a more integrative approach that would make it possible to act at the level of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention, and thus generate more potential health benefits [25].

The main strength of this study is that it enlisted the participation of 31 of the 34 institutions in Quebec’ health and social services network, making it possible to obtain a province-wide overview of the measures that the respondents said were put in place during the pandemic. Another strength of this project is that, through an advisory committee, all stakeholders in the Quebec health and social services network were involved from the outset of the research and at every important stage, thus achieving one of the fundamental objectives of participatory research: to produce relevant, useful and usable results. Meetings with the advisory committee played a significant role in guiding the development of the questionnaire used to survey HR staff. Also, an additional strength of this study is that it presented a series of organizational measures categorized according to targeted psychosocial risk factors in the workplace, which led to a better understanding of prevention targets in this public network. That being said, this approach also had certain limitations. Since more than one person from each institution could answer the questionnaire, it is possible that some measures were reported more than once. However, due to the way in which responsibilities are shared within HR management teams in the health and social services network, the same measure may have been applied differently across the establishments of a given institution (e.g. review of work schedules in a hospital centre versus a long-term care centre of the same institution). Since our objective was to obtain a global view of the measures put in place in the health and social services network, it was not essential to know exactly how many measures were implemented in each institution or its establishments. Moreover, even though HR advisors were credible informants, it was hard for them to answer for their institution as a whole in some cases. This explains why a fairly large proportion of respondents said that they were not aware of certain measures within their institution. Furthermore, the efficacy of measures was assessed solely on the basis of the respondents’ opinions. Therefore, the results cannot be used to comment on the actual effectiveness of measures on workers’ mental health, since no data to that effect were gathered from healthcare workers.

Lastly, the results pertaining to the psychosocial safety climate, particularly, the strong correlation between the PSC-4 indicator and the number of measures reported to have been implemented in various institutions have opened up new avenues of inquiry. Studies have shown that the implementation and success of organizational interventions aimed at protecting mental health in the workplace depend on, among other things, the importance and priority accorded by an organization to workplace psychological health and safety [45]. This concept of psychosocial safety climate refers to the practices, policies and procedures in place within an organization for the purpose of acting on psychological health problems [53]. Recent work has shown that organizations with a strong psychosocial safety climate have better results in mental health, particularly because it acts upstream from workplace psychosocial risk factors [49]. It would be interesting to study the correlation between the PSC-4 indicator and the number of implemented measures according to the type of measure (e.g. workload reduction measures, recognition measures). However, we must consider that the cross-sectional data in this study provide less conclusive support for a causal hypothesis. In addition, the data are based on the input of key informants rather than on that of all staff members in each institution (or a representative sample of them). Nonetheless, these analyses might serve as an exploratory first step toward proposing more in-depth study of the role of psychosocial climate safety, so as to understand the mechanisms whereby that climate, when favourable, can help to reduce mental health problems and burnout among managers, among other things [54]. Furthermore, the concept of psychosocial climate safety is still not used very often to understand intervention-related issues (processes, implementation, health effects) [49], highlighting the need for more studies in this area.

5. Conclusions

This research has provided an overview of the measures initiated or maintained in the institutions of Quebec’s health and social services network during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to protect workers’ mental health. Many of these measures have the potential to be effective in the post-pandemic COVID-19 era, when staffing shortages and work overload remain issues, because they target work organization and the psychosocial work environment. The study contributes to the literature on intervention processes by illustrating how perceptions of the effectiveness of interventions can be captured to some extent by surveying key interlocutors rather than by measuring perceived exposure to interventions directly with participants. However, for effective mental health protection, workplaces must engage in participatory prevention approaches involving workers to identify the specific risks in their workplace and the solutions best-suited to their needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P., N.N., C.B., M.-E.A, N.J., M.V., M.-C.L, and R.B..; methodology, M.P., N.N., C.B., M.-C.L., M.V.; software, R.B..; validation, M.P., N.N. and C.B.; formal analysis M.P. and M-E.A.; investigation R.B..; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.; writing—review and editing, N.N., C.B., M.-E.A, N.J., and R.B..; project administration M.P and N.N..; funding acquisition M.P., N.N., N.J., C.B., M.V., and M.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Quebec, Direction de la Recherche et de la Coordination interne (Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services, Department of Research and Internal Coordination).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was waived for this study due to the public availability of the data. An ethical exemption was provided by the Population Health and Primary Care Research Ethics Board of the CIUSSS de la Capitale-Nationale on 12 August 2020. Ethical principles were nevertheless followed, and data were anonymized.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable due to the publicly available nature of the data.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restriction.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Daniel Trudel (Université Laval) for his help with the Zotero bibliography. We are also grateful to Annik Trudelle (INSPQ) for her help during the analysis and to the Human resources manager of the community of practice for the distribution of the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chênevert, D.; Jézéquel, M. L’épuisement des professionnels de la santé au Québec. Gestion 2018, 43, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, C.S.; Jacobs, P.; Thanh, N.X.; Loong, D. An Estimate of the Cost of Burnout on Early Retirement and Reduction in Clinical Hours of Practicing Physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 2014, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, L. Health Workforce Burn-Out. Bull World Health Organ 2019, 97, 585–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamidi, M.S.; Bohman, B.; Sandborg, C.; Smith-Coggins, R.; Vries, P.; Albert, M.S.; Murphy, M.L.; Welle, D.; Trockel, M.T. Estimating Institutional Physician Turnover Attributable to Self-Reported Burnout and Associated Financial Burden: A Case Study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018, 18, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.K.; Gandrakota, N.; Cimiotti, J.P.; Ghose, N.; Moore, M.; Ali, M.K. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Nurse Burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, 2036469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, V.; Wade, D. Mental Health of Clinical Staff Working in High-Risk Epidemic and Pandemic Health Emergencies a Rapid Review of the Evidence and Living Meta-Analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Warren, N.; McMahon, L.; Dalais, C.; Henry, I.; Siskind, D. Occurrence, Prevention, and Management of the Psychological Effects of Emerging Virus Outbreaks on Healthcare Workers: Rapid Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2020, 369, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulia, P.; Mantas, C.; Dimitroula, D.; Mantis, D.; Hyphantis, T. General Hospital Staff Worries, Perceived Sufficiency of Information and Associated Psychological Distress during the A/H1N1 Influenza Pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, N.; Docherty, M.; Gnanapragasam, S.; Wessely, S. Managing Mental Health Challenges Faced by Healthcare Workers during Covid-19 Pandemic. BMJ 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976–e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.W.; Yau, J.K.Y.; Chan, C.L.W.; Kwong, R.S.Y.; Ho, S.M.Y.; Lau, C.C.; Lau, F.L.; Lit, C.H. The Psychological Impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Outbreak on Healthcare Workers in Emergency Departments and How They Cope. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Emerg. Med. 2005, 12, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux Rapport Annuel de Gestion Du Ministère de La Santé et Des Services Sociaux 2019-2020; 2020.

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux Portrait Du Personnel Des Établissements Publics et Privés Conventionnés Du Réseau de La Santé et Des Services Sociaux (2021-2022); 2022.

- Caillou, A. La Pire Réforme de La Santé. J. Devoir 2020.

- Carazo, S.; Pelletier, M.; Talbot, D.; Jauvin, N.; Serres, G.; Vézina, M. Psychological Distress of Healthcare Workers in Québec (Canada) during the Second and the Third Pandemic Waves. J Occup Env. Med 2022, 64, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citoyen, P. Rapport d’étape du Protecteur du citoyen : la COVID-19 dans les CHSLD durant la première vague de la pandémie 2020.

- De Serres, G.; Carazo, S.; Lorcy, A.; Villeneuve, J.; Laliberté, D.; Martin, R.; Deshaies, P.; Bellemare, D.; Tissot, F.; Adib, G.; et al. Enquête épidémiologique sur les travailleurs de la santé atteints par la COVID-19 au printemps 2020. Rapport de recherche. In Institut national de santé publique du Québec; Québec, QC, Canada, 2020 ISBN 978-2-550-87681-6.

- Me Géhane Kamel, B. Rapport d’enquête : Loi sur la recherche des causes et des circonstances des décès, pour la protection de la vie humaine, concernant 53 décès survenus dans des milieux d’hébergement au cours de la première vague de la pandémie de la COVID-19 au Québec 2020.

- Godlee, F. Protect Our Healthcare Workers. BMJ 2020, 369, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégin, D. Gestion de la présence au travail: assurance salaire...; MSSS: Québec, 2015; ISBN 978-2-550-63734-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux Étude Des Crédits 2017-2018, Réponse Aux Questions Particulières de l’opposition Officielle, Volume 3 Available online: https://www.msss.gouv.qc.ca/inc/documents/ministere/acces_info/seance-publique/etude-credits-2017-2018/2017-2018-Reponses-aux-questions-particulieres-Opposition-officielle-volume-3.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2018).

- Duchaine, C.S.; Aubé, K.; Gilbert-Ouimet, M.; Vézina, M.; Ndjaboué, R.; Massamba, V.; Talbot, D.; Lavigne-Robichaud, M.; Trudel, X.; Pena-Gralle, A.-P.B.; et al. Psychosocial Stressors at Work and the Risk of Sickness Absence Due to a Diagnosed Mental Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedhammer, I.; Bertrais, S.; Witt, K. Psychosocial Work Exposures and Health Outcomes: A Meta-Review of 72 Literature Reviews with Meta-Analysis. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2021, 47, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Martin, A.; Page, K.M.; Reavley, N.J.; Noblet, A.J.; Milner, A.J.; Keegel, T.; Smith, P.M. Workplace Mental Health: Developing an Integrated Intervention Approach. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamontagne, A.D.; Keegel, T.; Louie, A.M.; Ostry, A.; Landsbergis, P.A. A Systematic Review of the Job-Stress Intervention Evaluation Literature, 1990-2005. Int J Occup Env. Health 2007, 13, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano, D.; Hoven, H.; Siegrist, J. Effects of Organisational-Level Interventions at Work on Employees’ Health: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, B.; Møller, J.L.; Nordentoft, M.; Frydendall, K.B.; Bengtsen, E.; Jensen, A.B.; Garde, A.H.; Kompier, M.; Semmer, N.; Rugulies, R.; et al. How Effective Are Organizational-Level Interventions in Improving the Psychosocial Work Environment, Health, and Retention of Workers? A Systematic Overview of Systematic Reviews. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2023, 49, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagioti, M.; Panagopoulou, E.; Bower, P.; Lewith, G.; Kontopantelis, E.; Chew-Graham, C.; Dawson, S.; Marwijk, H.; Geraghty, K.; Esmail, A. Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2017, 177, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathisen, J.; Nguyen, T.-L.; Jensen, J.H.; Rugulies, R.; Rod, N.H. Reducing Employee Turnover in Hospitals: Estimating the Effects of Hypothetical Improvements in the Psychosocial Work Environment. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2021, 47, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolakakis, N.; Lafantaisie, M.; Letellier, M.-C.; Biron, C.; Vézina, M.; Jauvin, N.; Vivion, M.; Pelletier, M. Are Organizational Interventions Effective in Protecting Healthcare Worker Mental Health during Epidemics/Pandemics? Syst. Lit. Rev. Int J Env. Res Public Health 2022, 19, 9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theorell, T.; Hammarström, A.; Aronsson, G.; Träskman Bendz, L.; Grape, T.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Hall, C. A Systematic Review Including Meta-Analysis of Work Environment and Depressive Symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, I.E.H.; Nyberg, S.T.; Magnusson Hanson, L.L.; Ferrie, J.E.; Ahola, K.; Alfredsson, L.; Batty, G.D.; Bjorner, J.B.; Borritz, M.; Burr, H.; et al. Job Strain as a Risk Factor for Clinical Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with Additional Individual Participant Data. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.; Mantha-Bélisle, M.-M.; Vézina, M.; Denis, M.-A. Recueil de fiches portant sur les indicateurs de la Grille d’identification de risques psychosociaux du travail. Guide Prat. Prof. Inst. Natl. Santé Publique Qué. 2018.

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, 1990; ISBN 978-0-465-02897-9. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse Health Effects of High-Effort/Low-Reward Conditions. J Occup Health Psychol 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elovainio, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Vahtera, J. Organizational Justice: Evidence of a New Psychosocial Predictor of Health. Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. The Job Demands–Resources Model: Challenges for Future Research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, J.-P. Les 7 Pieces Manquantes Du Management Une Strategie d’amelioration Du Bien-Etre Au Travail et de l’efficacite Des Entriprises; 1st ed.; 2008; ISBN 978-2-89472-367-8.

- Aubouin-Bonnaventure, J.; Fouquereau, E.; Coillot, H.; Lahiani, F.J.; Chevalier, S. Virtuous Organizational Practices: A New Construct and a New Inventory. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 724956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entreprise en santé. Prévention, promotion et pratiques organisationnelles favorables à la santé et au mieux-être en milieu de travail; Première édition de la Norme nationale du Canada, 2020-02-13.; BNQ, Bureau de normalisation du Québec: Québec (Québec), 2020; ISBN 978-2-551-26530-5.

- Brookes, K.; Limbert, C.; Deacy, C.; O’Reilly, A.; Scott, S.; Thirlaway, K. Systematic Review: Work-Related Stress and the HSE Management Standards. Occup. Med. 2013, 63, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Dormann, C.; Idris, M.A. The PSC-4; a Short Tool (Chapitre 16); Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Switzerland, 2019.

- Idris, M.A.; Dollard, M.F.; Coward, J.; Dormann, C. Psychosocial Safety Climate: Conceptual Distinctiveness and Effect on Job Demands and Worker Psychological Health. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Dollard, M.F.; Tuckey, M.R.; Dormann, C. Psychosocial Safety Climate as a Lead Indicator of Workplace Bullying and Harassment, Job Resources, Psychological Health and Employee Engagement. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollard, M.F.; Opie, T.; Lenthall, S.; Wakerman, J.; Knight, S.; Dunn, S.; Rickard, G.; MacLeod, M. Psychosocial Safety Climate as an Antecedent of Work Characteristics and Psychological Strain: A Multilevel Model. Work Stress 2012, 26, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Bailey, T. Building Psychosocial Safety Climate in Turbulent Times: The Case of COVID-19. J Appl Psychol 2021, 106, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux Plan d’action national visant la prévention des risques en milieu de travail et la promotion de la santé globale 2019-2023. Québec 2019, 67.

- Institut national de la santé publique du Québec COVID-19 : Prévention et contrôle des infections | INSPQ Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/prevention-et-controle-des-infections (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Paillé, P.; Mucchielli, A. L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales; 4e ed.; Armand Colin: Paris, 2016.

- Dollard, M.F.; Bakker, A.B. Psychosocial Safety Climate as a Precursor to Conducive Work Environments, Psychological Health Problems, and Employee Engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 579–599. [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Lamarche, A.; Biron, C. When Bosses Are Burned out: Psychosocial Safety Climate and Its Effect on Managerial Quality. Int J Stress Manag 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).