1. Introduction

To function, a protein molecule acquires a unique conformation during the folding process [

1,

2]. If the protein does not fold into its native state, then it is not able to perform its function and may form aggregates [

3,

4]. Amyloid fibrils are a specific type of protein aggregates that contribute to the emergence of severe human diseases. Currently, more than 50 diseases are classified as amyloidosis, including type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s and Creutzfeldt-Jakob diseases and others disorders [

5,

6]. However, not all amyloids are associated with pathology. Some proteins form functional fibrils that serve a structural role or store biologically active molecules [

7,

8]. Due to the high stability of amyloid fibrils, several approaches are being developed for their use as high-strength biomaterials [

9,

10].

Amyloids are long, unbranched protein fibrils, that possess a distinctive characteristic: the cross-β-structure, composed of β-strands perpendicular to the aggregate axis, and hydrogen bonds between strands are parallel to the axis [

11,

12,

13]. There has been a surge in research on amyloid aggregation in the past years, with emphasis on investigating the structure of fibrils and the kinetics of their formation [

14,

15,

16,

17], while the conformational stability of amyloids and the methods of their dissociation remain near to unexplored. Studying the unfolding of amyloid is important for understanding the fundamental principles of protein aggregates stabilization. Moreover, knowledge of amyloid unfolding stages and stability is crucial for finding treatments for amyloid diseases. However, investigation of amyloids stability is difficult due to aggregates insolubility, heterogenicity, and high resistance to denaturation [

18,

19]. Therefore, to date, fibrils disassembly experiments have been carried out only for a few proteins [

20,

21,

22].

A standard approach for studying the stability of monomeric proteins is their equilibrium unfolding by a denaturant [

23,

24]. In order to investigate the stability of amyloid aggregates, similar approaches can be used. A number of works have been devoted to the study of the stages of amyloids unfolding by denaturants [

20,

21,

22]. Using this approach, the contribution of individual residues to the stabilization of prion protein (PrP) amyloids was determined [

22]. It was revealed that when insulin and β2-microglobulin fibrils undergo unfolding, intermediate aggregates are produced. The latter do not bind thioflavin T (ThT), but they do retain the characteristic morphology and the secondary structure of amyloids [

20].

This work aims to investigate effect of amino acid substitutions on the stability of amyloid relative to the unfolded state. ApoMb was chosen as the object for this study. This is an α-helical globular protein comprising 156 amino acid residues. Its structure includes eight helices, designated by letters from А to Н [

25,

26]. Folding of ApoMb occurs through the formation of a molten globule intermediate state, in which the A-, G-, and H-helices retain the native-like topology [

27,

28]. The precursor of ApoMb amyloids can be either an unfolded or an intermediate (molten globule) state of the protein [

29,

30,

31]. It also has been shown that the amyloid formation propensity of ApoMb increases with increasing degree of its native state destabilization [

31]. Experimental data showed that the ApoMb region corresponding to A-helix is the most amyloidogenic one [

30,

32]. Therefore, a substantial amount of data has been gathered so far regarding the folding and amyloid aggregation of ApoMb. This renders this protein a suitable model for investigating the stability of amyloid.

This study is focused on analyzing the stability of amyloids of ApoMb and its six mutant variants. To assess the stability of amyloids, they were unfolded by urea. Far ultraviolet circular dichroism (UV CD) was used to monitor changes in the secondary structure of aggregates as they unfolded. Additionally, blue native PAAG (BN-PAAG) electrophoresis was employed to record variations in the molecular weight of the aggregates. The data obtained allowed to reveal three stages of amyloids disassembly, namely the unfolding of amyloid secondary structure (i), dissociation of fibrils to intermediate aggregates (ii) and their subsequent disassembly to monomers (iii). Based on the results of amyloid unfolding transitions, we assessed the stability of amyloids and intermediate aggregates. The hydrophobicity of amino acid residues was found to be a key determinant of stabilization of these both aggregates’ types. The contribution of the studied residues to the stabilization of amyloids and intermediate aggregates was estimated.

2. Results

2.1. At a Temperature of 40 °С and pH 5.5 ApoMb Forms Amyloids

The aim of this work was to study the effect of amino acid substitutions on the stability of ApoMb amyloid fibrils. The hydrophobicity of amino acid residues is widely recognized as a key factor influencing the kinetic of proteins amyloid aggregation [

5,

15]. Therefore, we hypothesized that hydrophobicity may also play an important role in fibrils stabilization. We have chosen ApoMb residues from different regions of the protein for substitutions: V10 (A-helix), L115 (G-helix), and M131 (H-helix). For each position, two protein mutant forms with oppositely modified hydrophobicity were obtained. One substitution led to an enhanced hydrophobicity (V10F, L115F, M131W), while the other resulted in a reduced hydrophobicity (V10A, L115A, M131A). In addition, according to our previous results, these mutants differ significantly in the stability of the monomeric protein [

31]. Thus, the series of 6 obtained ApoMb mutant variants was created providing an appropriate platform for investigating the impact of monomeric protein stability and residue hydrophobicity on amyloid stability.

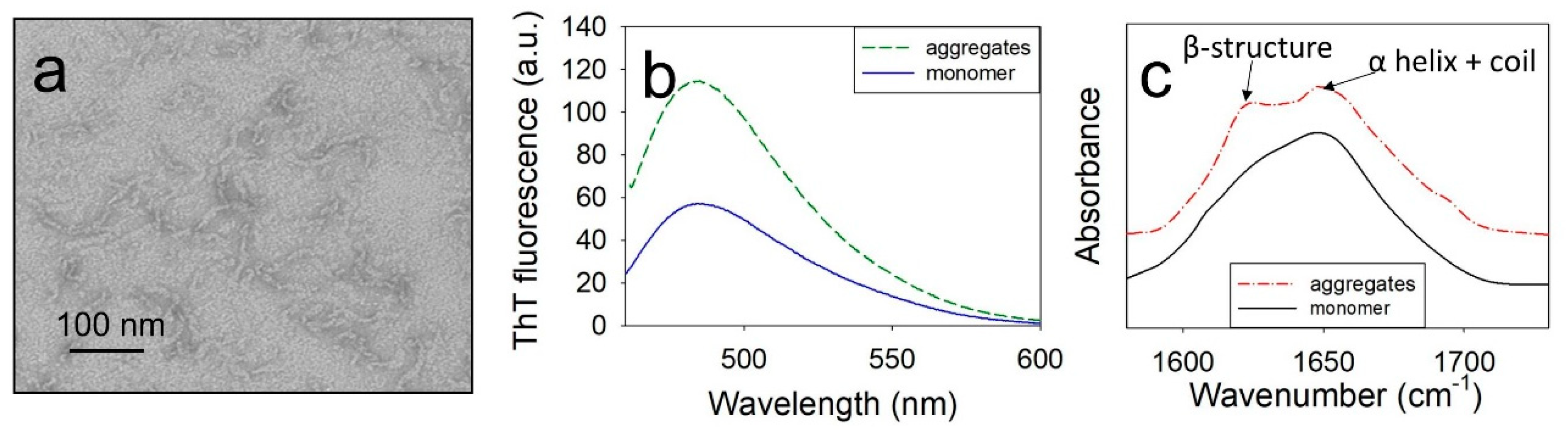

The aggregates of wild-type (WT) ApoMb and its mutant variants were formed by a 24-hours incubation of proteins at 40°C and pH 5.5. Structural features of aggregates were studied by ThT fluorescence, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and electron microscopy. As an example,

Figure 1 shows the results obtained for V10F variant, since this protein is characterized by high amyloidogenicity. Similar results were obtained for all studied proteins.

Electron microscopy findings have revealed that under the investigated conditions ApoMb forms twisted fibrillar aggregates that extend up to 100 nm in length (

Figure 1a). An increase in ThT fluorescence was observed for the formed fibrils, indicating the presence of the amyloid β-structure (

Figure 1b). Additionally, the presence of a cross-β-structure was confirmed by FTIR. The spectra of monomeric ApoMb V10F have one maximum at a wave number of 1650 cm

-1, where α-helices and a coil absorb (

Figure 1c). While in the spectra of aggregates second peak at 1620 cm

-1, characteristic for an amyloid cross-β-structure appears [

33]. Thus, based on the obtained data, it can be concluded that ApoMb and its mutant forms at a temperature of 40°С and рН 5.5 form amyloid fibrils.

2.2. Changes in the Secondary Structure During Amyloids Unfolding

The first goal of this work was to choose approaches for studying the amyloids stability. The common method for evaluating the stability of monomeric proteins is by measuring their equilibrium unfolding transition through denaturation [

23,

24]. Similar approaches, with some modification, have also been successfully used to assess amyloid stability [

20,

21,

22]. The unfolding of protein structure at different denaturants concentrations was usually monitored by spectral methods, among which ThT fluorescence is most often used for detection of amyloids. However, it turned out that this method is not applicable for studying the urea unfolding of ApoMb fibrils. Even at a low denaturant concentration, when there is no detectable change in ApoMb aggregates secondary structure measured by CD, we observed a decrease in the intensity of ThT fluorescence. This implies that low urea concentration rather induces dissociation of the ThT bound to ApoMb amyloid than destruction of fibrils structure. Therefore, in this work, the unfolding of the ApoMb amyloids by urea was studied using the far UV CD method.

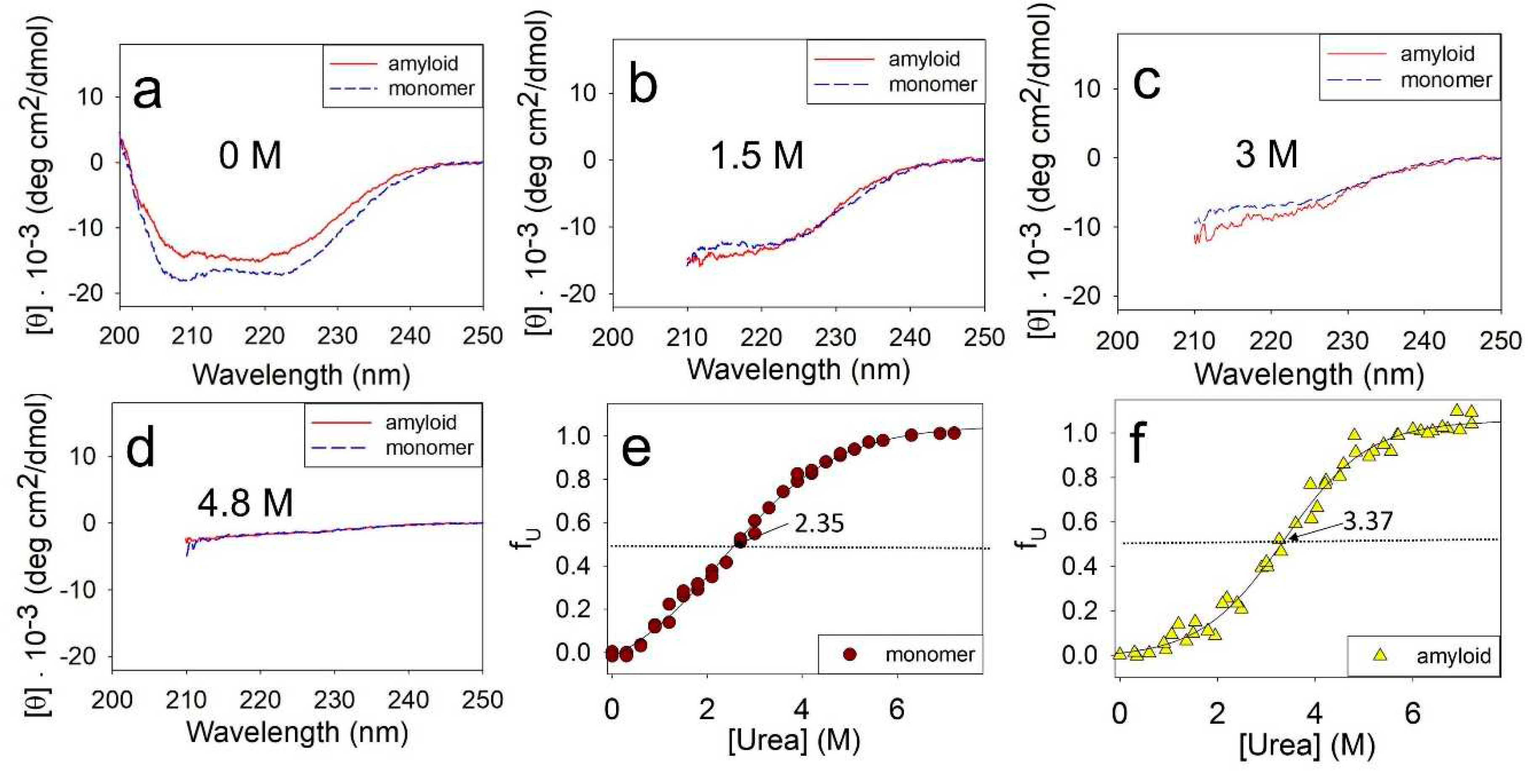

The stability of the monomeric ApoMb and amyloids was evaluated by incubating them at different urea concentrations followed by measuring their CD spectra.

Figure 2 compares the unfolding of monomeric ApoMb V10F variant and its amyloids by urea. The data show that in the absence of denaturant the spectrum of monomer has two distinct minima at wavelengths of 208 nm and 222 nm, which are indicative of α-helical protein structure (

Figure 2a). The spectrum of amyloid has wide minimum in the range of 210-220 nm, which is a feature of the protein with β-structure. Upon the addition of urea, the unfolding of protein and aggregates can be clearly observed through a decrease in the molar ellipticity as shown in

Figure 2b-d. Due to absorption of urea in the wavelengths up to 210 nm, the CD spectra are presented in the range of 210-250 nm in

Figure 2b-d. When the urea concentration reaches 4.8M, both the monomeric protein and amyloid are fully unfolded. This is evident from the molar ellipticity value of 0-2 deg·cm

2/dmol in the wavelength range of 215-250 nm (

Figure 2d).

The obtained spectra were used to plot the unfolding transitions of ApoMb monomer and amyloids based on their molar ellipticity at 222 nm (

Figure 2e,f). The transition midpoint of monomeric ApoMb is at 2.35 M urea (

Figure 2e). While for amyloid this value shifts towards higher urea concentrations and corresponds to 3.37 M (

Figure 2f). These data evidence that the amyloid aggregates are much more stable as compared to the monomer. Thus, using CD to measure amyloid unfolding by urea allows evaluation of the fibrils’ secondary structure stability relative to the unfolded protein.

2.3. Influence of Amino Acid Substitutions on the Stability of Amyloids Secondary Structure

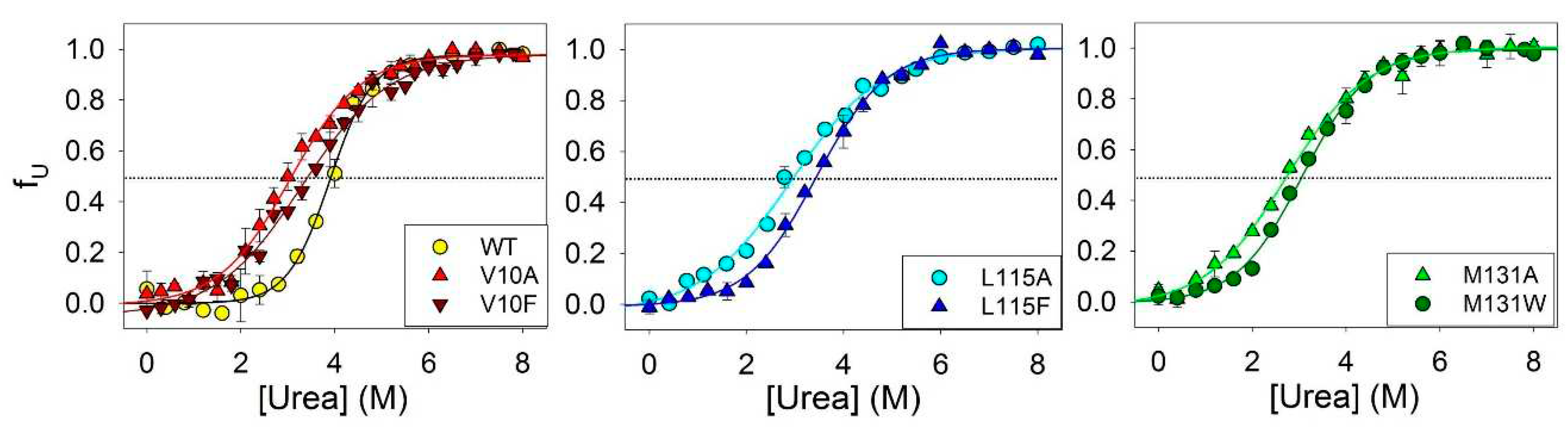

To investigate the influence of amino acid substitutions on the stability of amyloids secondary structure, we conducted experiments to urea unfolding of fibrils of ApoMb and its mutant variants.

Figure 3 shows the amyloids’ unfolding transitions obtained by far UV CD. The values of the midpoints of denaturation transitions ([urea]

1/2β-U) were calculated from sigmoidal approximation of the obtained graphs (

Table 1). These values serve as quantitative characteristic of the stability of the amyloids’ secondary structure relative to the unfolded protein.

Our next aim was to determine whether the stability of amyloids depends on the stability of the monomeric protein. Under the conditions appropriate for amyloid aggregation (рН 5.5, 40°C), ApoMb molecules adopt either a native or an intermediate (molten globule) state [

31]. The populations of these states can be used as a measure of the monomeric protein structure's stability. The fractions of the native state (f

N) of ApoMb variants under studied conditions were calculated in our previous work [

31] and listed here (

Table 1).

Figure 4a shows the midpoints of amyloid denaturation plotted versus the fractions of the native state (f

N) of the ApoMb variants. The graph’s low correlation coefficient (r=0.51) indicates that the stability of amyloids weakly depends on the stability of the monomeric protein.

Then we hypothesized that the hydrophobicity of amino acid residues may determine the stability of fibrils, as hydrophobic interactions are known to play an important role in the formation of aggregates. However, the correlation between the midpoints of denaturing transitions and the change in the hydrophobicity resulting from mutations plotted for all studied variants is weak (r=0.44) (

Figure 4b). When analyzing these results, it is important to take into account that that various residues may be involved to different extents in the formation of intermolecular interactions. In other words, one residue can be entirely enclosed within the aggregates structure, whereas another residue of the same type can form contacts only by part of its surface. To investigate the impact of residues hydrophobicity on amyloid stability, it is crucial to compare the stability of fibrils of mutants with substitutions at the same position by different residues.

Figure 4c presents this comparison and reveals a general feature for all three positions analyzed. It shows that the amyloids of mutants with substitutions for a more hydrophobic residue is significantly more stable compared to the amyloids of variants with substitutions for a less hydrophobic alanine. These data indicate that increasing in the residue hydrophobicity of ApoMb mutants leads to the stabilization of amyloid fibrils.

2.4. Changes in the Molecular Weight of the Aggregates during Amyloids Unfolding

Far UV CD method allowed us to study urea-induced transitions of ApoMb fibrils to unfolded protein and quantify the stability of amyloids secondary structure. However, CD data cannot provide information regarding change in oligomerization degree of protein aggregates accompanying the unfolding process of the fibrils. For detailed study of amyloid unfolding it is crucial to determine the molecular weight of protein aggregates applying an appropriate experimental method. To analyze the size of proteins, the gel filtration method is widely used. However, it’s using in the field of amyloid aggregation is often limited due to nonspecific sorption and column clogging by aggregating proteins. Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments are quite time-consuming and complicated by the influence of particles morphology on sedimentation [

35]. Thus, we have selected blue native PAGE (BN-PAAG) electrophoresis as the method to evaluate the molecular mass of aggregates in the process of ApoMb amyloid unfolding.

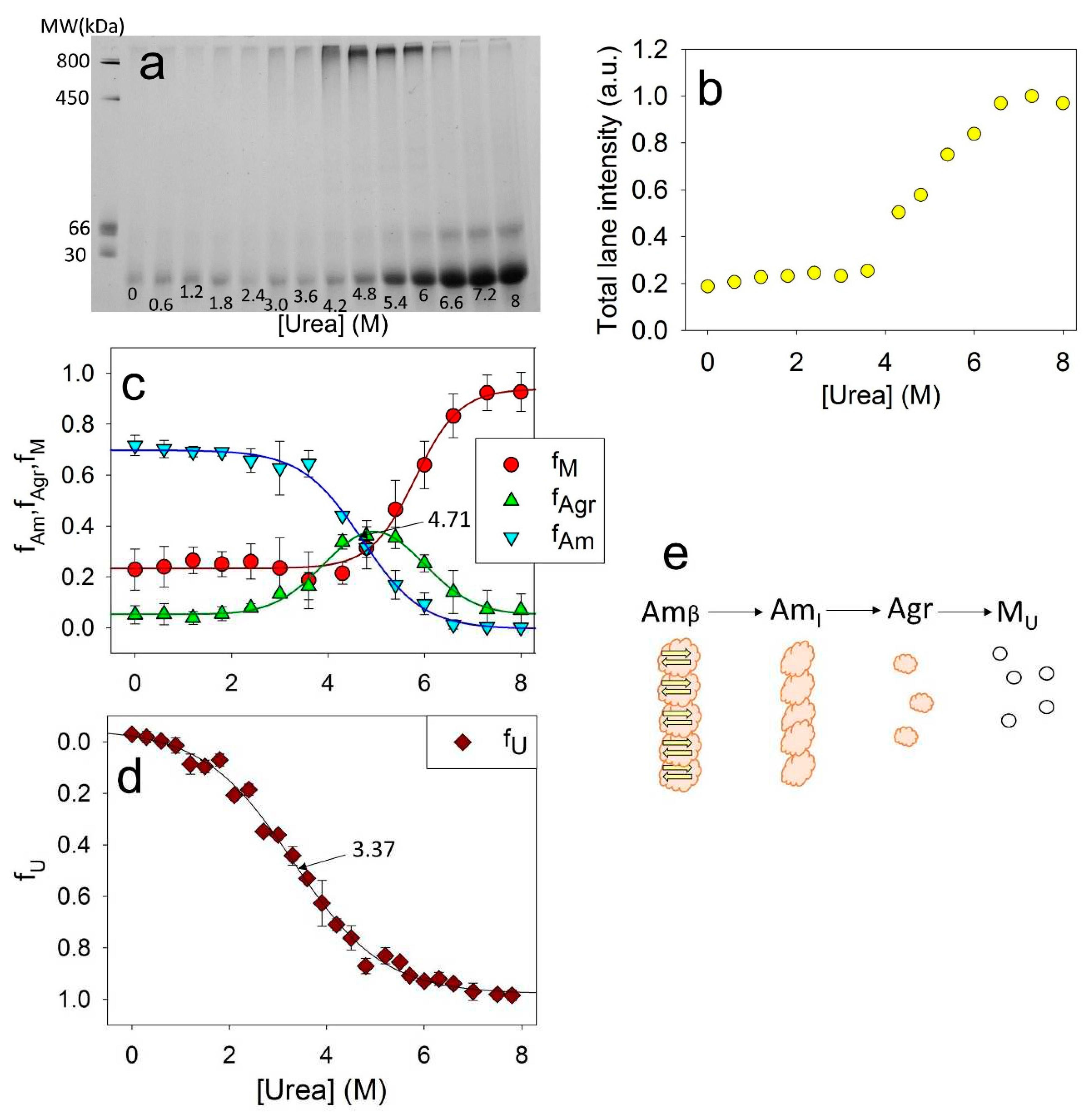

For this study ApoMb fibrils were incubated at various concentrations of urea for 24 hours. Then, electrophoresis was carried out without denaturant, with the same amount of protein applied to the slot for all samples. The resulting electrophoregram for the mutant form V10F is shown in

Figure 5a. On the electrophoregram, the monomeric protein band is clearly visible at the bottom of the gel. With an increase in the urea concentration, an increase in this band intensity is observed, indicating the aggregates’ dissociation. When urea concentrations range was of 4-6 M, a distinct band appears in the upper section of the gel. This band corresponds to aggregates with a molecular weight of about 1 MDa and provides evidence that amyloid unfolding by urea occurs through the formation of these intermediate aggregates. Also, at high urea concentrations, an additional band with an apparent molecular mass of about 50 kDa is visible, which are supposed to be attributed to the ApoMb dimer. Therefore, it seems that dimers formed during amyloid unfolding are highly stable and do not dissociate even at high concentrations of denaturant.

Although the same amount of the protein was applied to each slot, the total intensities of the lanes vary and show an upward trend as the urea concentration increases. This indicates that the amyloid aggregates, the fraction of which is maximum at low urea, are too big to enter the electrophoretic gel and do not contribute lane intensity.

Figure 5b shows the dependence of the total intensities of the lanes on the urea concentration. When the denaturant concentration reaches 6.2 M, the graph reaches a plateau, indicating the absence of any aggregates that cannot enter into the gel. So, at urea concentration of 8M, the amyloids completely dissociate; therefore this method can be used to evaluate the stability of ApoMb aggregates as they unfold. From the data obtained, the fraction of large amyloid aggregates

can be calculated as:

where

is the maximum intensity at the baseline at high (7.5 – 8 M) urea concentration, and x is the urea concentration, (М),

– total intensity of the lane at urea concentration х.

The fractions of monomers f(M) and of 1 MDa intermediate aggregates f(Agr) can be determined by analyzing the intensity of the corresponding bands in the gel.

Figure 5c shows the dependence of the fractions of the monomers f(M), aggregates f(Agr) and amyloids f(Am) on the urea concentration. Since the intensity of the dimer band is insignificant, the calculated value f(M) is the sum of the monomer and dimer bands. The graphs clearly show that decreasing amyloid levels results in an increase in intermediate aggregates, while the disassembly of the latest coincides with accumulation of monomeric protein.

The combination of CD and BN-PAAG electrophoresis data analysis provides valuable insights into the stages of ApoMb amyloid unfolding. The midpoint of amyloid unfolding transition, measured by CD, is found to be at 3.37 M (

Figure 5d,

Figure 2f). While, the midpoint of the amyloid's dissociation graph, determined by BN-PAAG electrophoresis, is shifted towards higher urea concentrations and corresponds to 4.71 M (

Figure 5c). Therefore, at the first stage of amyloids unfolding, the loss of amyloids secondary structure occurs (Am

β → Am

I). Then the fibrils dissociate into intermediate aggregates (Am

I → Agr). At the final stages of amyloid unfolding, intermediate aggregates dissociate into a monomeric protein (Agr → M). The suggested scheme of the ApoMb amyloid unfolding is shown in

Figure 5e.

2.5. Influence of Amino Acid Substitutions on the Stability of Amyloids Relative to the Intermediate Aggerates and the Stability of Intermediate Aggregates Relative to the Unfolded Monomer

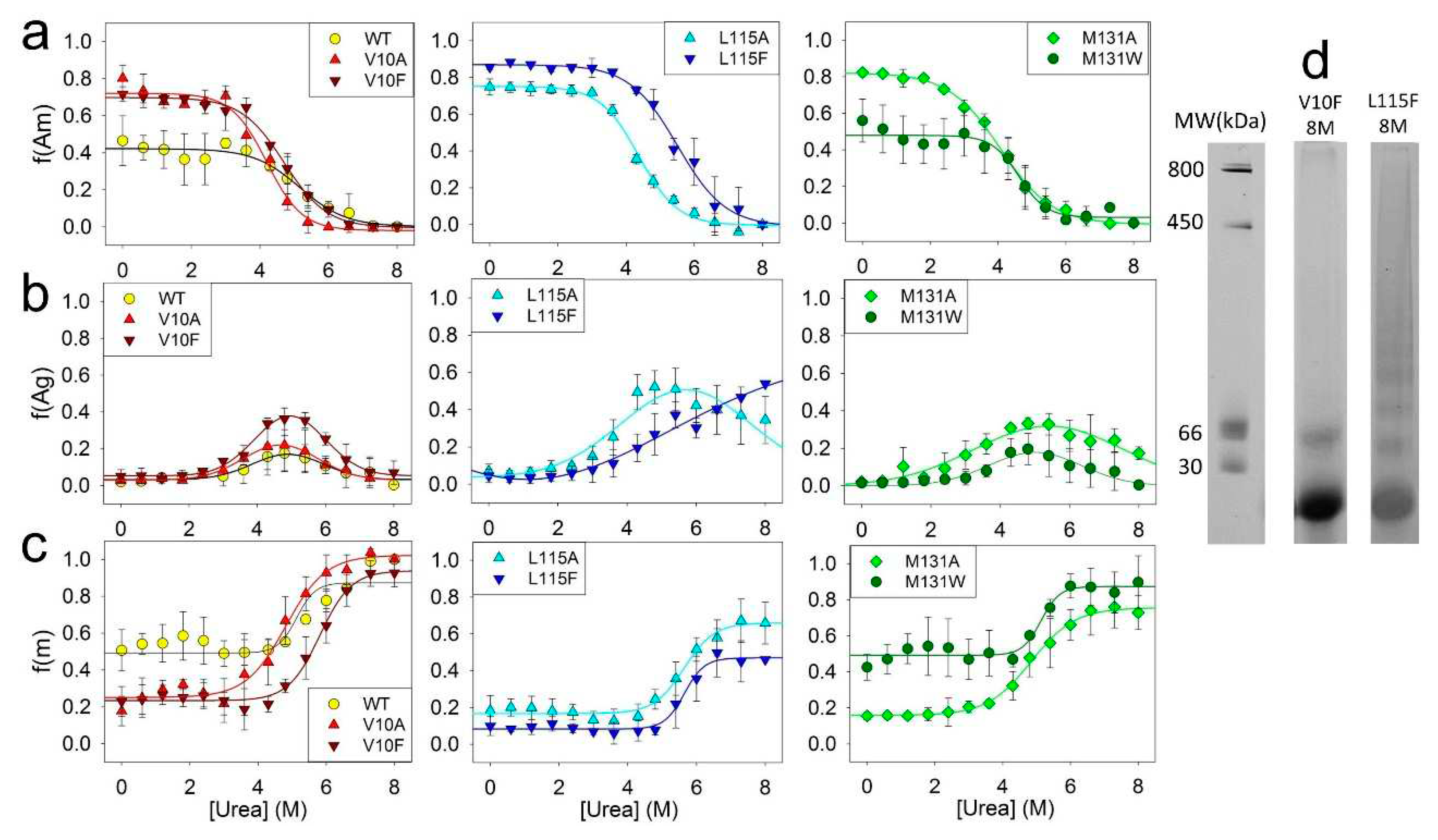

To investigate the impact of amino acid substitutions on the stability of fibrils and intermediate aggregates, the unfolding of amyloids formed by ApoMb mutant variants was studied by BN-PAAG electrophoresis. From the obtained data the fractions of amyloids f(Am), intermediate aggregates f(Agr), and monomers f(M) versus urea concentration were calculated (

Figure 6).

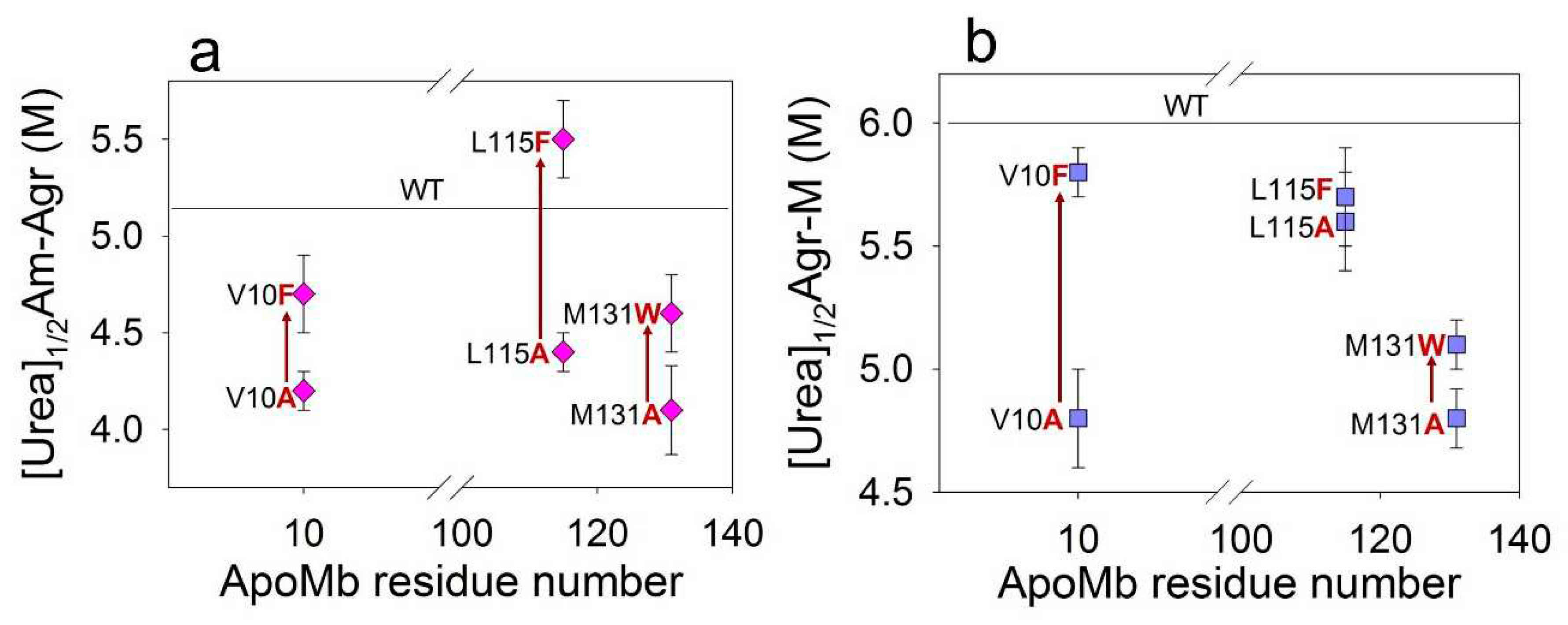

The dependence of the fractions of ApoMb amyloids on urea concentration reflects the dissociation of fibrils to intermediate aggregates (Am-Agr) (

Figure 6a). Therefore, the midpoints of these transitions ([urea]

1/2 Am-Agr) represent the stability of amyloids relative to intermediate aggregates. ApoMb variants transition midpoints calculated from the sigmoidal approximation of obtained graphs are presented in the

Table 1. The data analysis shows that the hydrophobicity of amino acid residue substitutions is the determining factor for the stability of ApoMb mutants’ amyloids (

Figure 7a). Fibrils of variants with substitutions that enhance hydrophobicity demonstrate higher stability as compared to those with substitutions for the less hydrophobic alanine. This result is similar to that obtained for unfolding of the amyloids secondary structure studied by the CD (

Figure 4с).

Moreover, the obtained data also demonstrate that fractions of amyloid of the ApoMb variants differ before urea addition (points at 0M urea on the

Figure 6a). These values represent the fractions of amyloids in the solution once the aggregation process is complete and serve as measures of the ApoMb variants’ aggregation propensities [

31]. The transition Am-Agr midpoints calculated from the graphs are independent on the fraction of amyloids prior to the denaturant addition, and are determined solely by the stability of the fibrils.

Figure 6b represents the fraction of intermediate aggregates as a function of urea concentration. In these graphs the fraction of aggregates at a urea concentration of 8M is important characteristic. The presence of a non-zero value indicates the existence of a stable fraction of aggregates that remain nondissociated even in the presence of 8M urea.

The figure shows that the variants with substitutions at position L115 (L115A and L115F), as well as the M131A protein, exhibit a remarkably high stability of aggregates. Features of these aggregates is clearer from

Figure 6d that compares the electrophoregram lanes of amyloids incubated in 8M urea for variants V10F and L115F. For the V10F variant, a complete dissociation of aggregates by urea is observed, leaving only the monomers and a small fraction of dimers in the solution. In contrast, for the L115F variant, most of aggregates are resistant to denaturation: on the electrophoregram at 8M urea one can see discrete bands with a molecular weight of 400 kDa and below. Therefore, urea-resistant aggregates (400 kDa) are distinct from described earlier intermediate aggregates formed during amyloid unfolding (1 MDa), and represent a specific aggregates type. It can be assumed that mutations L115A, L115F, and M131A cause destabilization and structural changes in ApoMb, resulting in the formation of relatively small and highly stable aggregates.

The graphs of the increase in the fraction of monomer with urea concentration indicate the dissociation of intermediate aggregates to monomer (Agr-M) (

Figure 6c). From the graph’s approximation by a sigmoid function, the transition midpoints ([urea]

1/2 Agr-M) were calculated (

Table 1). These values are the measure of the stability of aggregates relative to the unfolded monomeric protein. The results show that the stability of intermediate aggregates of the ApoMb variants increases with increasing hydrophobicity of substituted amino acid residues (

Figure 7b). The impact of the hydrophobicity effect varies significantly depending on the position of the substitution; for proteins with mutations at position L115, there is no reliable difference in the value of the transition midpoints. However, L115F variant forms a greater fraction of urea-resistant aggregates then the L115A protein (

Figure 6b). This finding provides further evidence of the higher stability of the L115F aggregates and supports the conclusion that enhancing the hydrophobicity of the residues contributes to the stabilization of ApoMb variants' aggregates.

3. Discussion

The study of conformations of the polypeptide chain is crucial to understand the mechanism of proteins functioning and the development of diseases related to protein misfolding. To date, the folding of globular proteins has been well studied. For many proteins, several conformational states have been described and energy profiles of the folding process have been drawn [

23,

24,

28]. However, the energy landscape of a polypeptide chain includes not only monomeric molecules, but also various types of aggregates [

36]. A promising frontier in protein physics lies in the investigation of the structural characteristics and the stability of aggregated conformations.

The aim of our work was to reveal the determinants of ApoMb amyloids stability. This work has developed new approaches for studying the stability of fibrils by monitoring their urea unfolding. An analysis of the unfolding transitions recorded by CD and BN-PAAG electrophoresis allowed determination of the stages of amyloids unfolding. At the first step, the secondary structure of protein molecules within amyloid unfolds (

Figure 5e). Then the dissociation of fibrils to intermediate aggregates with the molecular weight of about 1 MDa is observed. At the final stages, these aggregates dissociate into monomeric molecules, while a number of mutant variants into 400 kDa urea-resistant aggregates.

By studying the amyloid stability of ApoMb mutant variants, the effect of amino acid substitutions on the stages of amyloid unfolding was determined. It has been shown that an increase in the residue hydrophobicity of mutant forms leads to the stabilization of amyloid fibrils relative to the intermediate aggregates and intermediate aggregates relative to the monomeric molecules.

Considering all the proteins, we see a definite but week correlation of fibrils stability and the change of hydrophobicity of ApoMb mutant variants (

Figure 5b). Stabilization of amyloids with increasing residues hydrophobicity was discovered due to comparison of the amyloid stability of mutants with substitutions at the same position by residues differing in the hydrophobicity. This result can be explained by the fact that different residues are involved to various degrees in the formation of intermolecular interactions in the amyloid structure. It can be assumed that the difference in the stability of amyloids of mutants with substitutions in the same position by residues differing in hydrophobicity (∆[urea]

1/2) allows evaluating the contribution of this residue to the formation of intermolecular interactions in the aggregates structure.

Table 2 presents these values for both amyloids and intermediate aggregates, calculated using the following formulas:

Based on the obtained data, it is evident that the value ∆[urea]1/2Am-Agr is the highest (=1 M) for variants with substitution at L115 position. Therefore, the L115 residue plays a crucial role in stabilizing amyloids. At the same time, the value of ∆[urea]1/2Agr-M for proteins with substitutions at position V10 is significantly higher (=0.9 M), compared to other positions studied. Therefore, the interactions formed by the V10 residue are most important for stabilizing the intermediate aggregates. The stability of the secondary structure of amyloids in mutant variants, which vary in hydrophobicity, is nearly identical for all position

Thus, in this work the influence of amino acids substitutions in ApoMb on the stability of amyloids has been investigated. Based on the experimental results the contribution of studied residue to fibril stabilization has been assessed. The data obtained provide an insight into understanding of the fundamental features of stabilization of protein aggregates, and presented approaches can be used in further investigations of the stability of amyloid fibrils formed by different proteins.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Protein Expression and Purification

Plasmids containing the genes of sperm whale ApoMb mutated forms were obtained using a 7 QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, USA) with the plasmid pET17b as a template (a kind gift from Dr. P.E. Wright). ApoMb and its variants were isolated and purified after expression of appropriate plasmids in Escherichia coli (E.coli) BL21 (DE3) cells as described previously [

37].

4.2. Amyloids Formation

Lyophilized proteins were dissolved in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, рН 5.5. Then the poorly dissolved material was removed by centrifugation using a Beckman 100 ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) at 90,000 g for 30 min at a temperature of 4°С. For amyloids formation ApoMb and its variants were incubated for 24 h at a temperature of 40°C and pH 5.5 at a concentration of 5 mg/ml.

Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. Absorption spectra were measured on a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) in the 220-450 nm range at a temperature of 25°С. The extinction coefficients were calculated from the amino acid sequences and taken

= 0.88 for WT ApoMb and its mutated variants V10A, V10F, L115A, and L115F; the value of

= 1.2 was used for M131W variant [

38].

4.3. Electron Microscopy

The samples for electron microscopy studies were prepared according to the negative staining method, described earlier [

39]. Briefly, a cooper 400-mesh grid (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA, USA) coated with a formvar film was mounted on the protein sample drop (6 µM). After 5 min of adsorption, the grid with the preparation was negatively stained for 2 min with a 1% aqueous solution of uranyl acetate. Micrographs were obtained using a transmission electron microscope JEM 1200 EX (Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) at an 80 kV accelerating voltage.

4.4. Fluorescence Spectra

Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence spectra were measured using a Varian Cary Eclipse spectrofluorimeter (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) at a temperature of 25°C. Protein solutions with a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml (5 µM) were used; the dye concentration was 25 µM. Measurements were carried out in a 3 × 3 mm cuvette. The excitation wavelength was 450 nm, and the emission spectra were recorded in the range 460–600 nm.

4.5. Fourier Transforms Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Infrared spectra were recorded at 25°С on a Fourier IR-spectrometer Nicolet 6700 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) using 5 mg/ml protein concentration. Protein samples were sandwiched between two CaF2 plates with an optical path length of 5.8 µm. The spectra (averaged from 256 scanning runs) were measured at a resolution of 4 cm-1. Subtraction of buffer spectra and suppression of water steam spectra were conducted using the OMNIC software.

4.6. Amyloid Unfolding by Urea

For measurements of the urea unfolding transitions samples were done as follows. The monomeric protein and amyloid were subjected to incubation at different urea concentrations, ranging from 0 to 8 M, for a period of 24 hours at a temperature of 20°C. The protein concentration during incubation was 0.5 mg/ml.

4.7. Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD spectra measurements were performed on a Chirascan spectropolarimeter (Applied Photophysics, London, England) with 0.1 cm path length cuvette. The protein concentration was 0.1 mg/ml. Spectra were recorded in the range 190-250 nm at a temperature of 25°С. Molar ellipticity

was calculated according to the formula:

where

is the ellipticity value measured at a wavelength of λ, mdeg; МRW is the average residue molecular weight calculated from the amino acid sequence, Da; l is the optical path length, mm; c is the protein concentration, mg/ml. Unfolding transitions were plotted by the molar ellipticity value at a wavelength 222 nm.

4.8. Blue Native-PAAG (BN-PAAG) Electrophoresis

Blue native electrophoresis was performed according to [

40] with modifications. Briefly, stacking and gradient resolving gels with 5% and 6-21% acrylamide concentrations, respectively. The gel-buffer contained 50mM bis-Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 0.5M ε-aminocaproic acid; cathode buffer - 15mM bis-Tris, pH 7.0, 50mM Tricine, 0.02% Coomassie blue G250, anode buffer- 50mM bis-Tris-HCl, pH 7.0. Protein sample aliquots were supplemented by sample buffer to achieve final concentration of 30mM bis-Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 6% Glycerol, 0.04% Coomassie blue G250. Gels were fixed overnight in the 40% Ethanol, 10% acetic acid solution and stained by colloidal Coomassie blue G250. The bands staining intensity were calculated using Total Lab software.

Author Contributions

Methodology, N.R., V.B. and V.M.; investigation, N.K., V.M., N.I., V.B., and N.R; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, A.F. and V.M.; visualization, N.R.; supervision, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to P.E. Wright for providing plasmid with ApoMb gene, to D.A. Dolgikh for construction of plasmids containing ApoMb mutants, to S.E. Permyakov and A.S. Kazakov for assistance in measuring FTIR spectra. Assistance in obtaining microscopy images was provided by the Electron Microscopy Core Facilities of the Pushchino Center of Biological Research No. 670266.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

References

- Dill, K.A.; MacCallum, J.L. The protein-folding problem, 50 years on. Science 2012, 338, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, C.M. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature 2003, 426, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T.R.; Radford, S.E. Folding versus aggregation: polypeptide conformations on competing pathways. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 469, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadanza, M.G.; Jackson, M.P.; Hewitt, E.W.; Ranson, N.A.; Radford, S.E. A new era for understanding amyloid structures and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiti, F.; Dobson, C.M. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006, 75, 333–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, T.P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Dobson, C.M. The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otzen, D.; Riek, R. Functional amyloids. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019, 11, a0338608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.K.; Perrin, M.H.; Sawaya, M.R.; Jessberger, S.; Vadodaria, K.; Rissman, R.A.; Singru, P.S.; Nilsson, K.P.R.; Simon, R.; Schubert, D.; Eisenberg, D.; Rivier, J.; Sawchenko, P.; Vale, W.; Riek, R. Functional amyloids as natural storage of peptide hormones in pituitary secretory granules. Science 2009, 325, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, T.P.J.; Mezzenga, R. Amyloid fibrils as building blocks for natural and artificial functional materials. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 6546–6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, C.E.; Woolfson, D.N. Engineered and designed peptide-based fibrous biomaterials. Corr. Opin. in Solid. State and Material Sci. 2004, 8, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D.; Jucker, M. The amyloid state of proteins in human diseases. Cell 2012, 148, 1188–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makin, O.S.; Atkins, E.; Sikorski, P.; Johansson, J.; Serpell, L.C. Molecular basis for amyloid fibril formation and stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2005, 102, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tycko, R. Solid-state NMR studies of amyloid fibrils structure. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2011, 62, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomakin, A.; Chung, D.S.; Benedek, G.B.; Kirschner, D.A.; Teplow, D.B. On the nucleation and growth of amyloid beta-protein fibrils: detection of nuclei and quantification of rate constants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F.; Stefani, M.; Taddei, N.; Ramponi, G.; Dobson, C.M. Rationalization of the effects of mutations on peptide and protein aggregation rates. Nature 2003, 424, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boopathi, S.; Poma, A.B.; Garduno-Juarez, R. An overview of several inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease: characterization and failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmachari, S.; Paul, A.; Segal, D.; Gazit, E. Inhibition of amyloid oligomerization into different supramolecular architectures by small molecules: mechanistic insights and design rules. Future Med. Chem. 2017, 9, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimoto, T.; Sakurai, K.; Okamoto, A.; Chatani, E.; Hoshito, M.; Hasegawa, K.; Naiki, H.; Goto, Y. Conformational stability of amyloid fibrils of beta2-microglobulin probed by guanidine-hydrochloride-induced unfolding. FEBS Lett. 2004, 576, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazit, E. The “Correctly Folded” state of proteins: is it a metastable state? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2002, 41, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, S.; So, M.; Adachi, M.; Kardos, J.; Akazawa-Ogawa, Y.; Hagihara, Y.; Goto, Y. Thioflavin T-silent denaturation intermediates support the main-chain-dominated architecture of amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3937–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulatsky, M.I.; Sulatskaya, A.I.; Stepanenko, O.V.; Povarova, O.I.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Turoverov, K.K. Denaturant effect on amyloid fibrils: declasterization, depolymerization, denaturation and reassembly. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Breydo, L.; Makarava, N.; Yang, Q.; Bocharova, O.V.; Baskakov, I.V. Site-specific conformational studies of prion protein (PrP) amyloid fibrils revealed two cooperative folding domains within amyloid structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9090–9097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samatova, E.N.; Katina, N.S.; Balobanov, V.A.; Melnik, B.S.; Dolgikh, D.A.; Bychkova, V.E.; Finkelstein, A.V. How strong are side chain interactions in the folding intermediate? Protein Sci. 2009, 18, 2152–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stagg, L.; Samiotakis, A.; Homouz, D.; Cheung, M.S.; Wittung-Stafshede, P. Residue-specific analysis of frustration in the folding landscape of repeat beta/alpha protein apoflavodoxin. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 396, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliezer, D.; Yao, J.; Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Structural and dynamic characterization of partially folded states of apomyoglobin and implications for protein folding. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998, 5, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecomte, J.T.; Kao, Y.H.; Cocco, M.J. The native state of apomyoglobin described by proton NMR spectroscopy: the A-B-G-H interface of wild-type sperm whale apomyoglobin. Proteins 1996, 25, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughson, F.M.; Wright, P.E.; Baldwin, R.L. Structural characterization of a partly folded apomyoglobin intermediate. Science 1990, 249, 1544–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, C.; Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E. Identification of native and non-native structure in kinetic folding intermediates of apomyoglobin. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 355, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fandrich, M.; Forge, V.; Buder, K.; Kittler, M.; Dobson, C.M.; Diekmann, S. Myoglobin forms amyloid fibrils by association of unfolded polypeptide segments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15463–15468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirangelo, I.; Malmo, C.; Casillo, M.; Mezzogiorno, A.; Papa, M.; Irace, G. Tryptophanyl substitutions in apomyoglobin determine protein aggregation and amyloid-like fibril formation at physiological pH. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 45887–45891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, N.S.; Balobanov, V.A.; Ilyina, N.B.; Vasiliev, V.D.; Marchenkov, V.V.; Glukhov, A.S.; Nikulin, A.D.; Bychkova, V.E. sw ApoMb amyloid aggregation under nondenaturing conditions: the role of native structure stability. Biophys. J. 2017, 113, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picotti, P.; Franceschi, G.D.; Frare, E.; Spolaore, B.; Zambonin, M.; Chiti, F.; Polverino de Laureto, P.; Fontana, A. Amyloid fibril formation and disaggregation of fragment 1-29 of apomyoglobin: insights into the effect of pH on protein fibrillogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 367, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandomeneghi, G.; Krebs, M.R.H.; McCammon, M.G.; Fandrich, M. FTIR reveals structural differences between native beta-sheet proteins and amyloid fibrils. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 3314–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauchere, J.L.; Pliska, V. Hydrophobic parameters-p of amino acid side-chains from the partitioning of N-acetyl aminoacid amide. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1983, 18, 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck, P.; Perugini, M.A.; Gonzales, N.R.; Howlett, G.J.; Schubert, D. Size-distribution analysis of proteins by analytical ultracentrifugation: strategies and application to model system. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 1096–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamcik, J.; Mezzenga, R. Amyloid polymorphism in the protein folding and aggregation energy landscape. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 8370–8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baryshnikova, E.N.; Melnik, B.S.; Finkelstein, A.V.; Semisotnov, G.V.; Bychkova, V.E. Three-state protein folding: experimental determination of free-energy profile. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 2658–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.C.; von Hippel, P.H. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 182, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchenkov, V.; Ivashina, T.; Marchenko, N.; Ryabova, N.; Selivanova, O.; Timchenko, A.; Kihara, H.; Ksenzenko, V.; Semisotnov, G. In vivo incorporation of photoproteins into GroEL chaperonin retaining structural and functional properties. Molecules 2023, 28, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schagger, H.; Jagow, G. Blue native electrophoresis for isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form. Anal Biochem. 1991, 199, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Electron image of aggregates, formed by V10F ApoMb (a); ThT fluorescence (b); infrared spectra (с) of aggregates and monomeric protein.

Figure 1.

Electron image of aggregates, formed by V10F ApoMb (a); ThT fluorescence (b); infrared spectra (с) of aggregates and monomeric protein.

Figure 2.

Far UV CD spectra of monomer and amyloid of ApoMb V10F at various urea concentrations, mentioned at the figures (a-d), normalized unfolding transitions of monomer (e) and amyloid (f). Solid lines (e,f) are the result of sigmoidal approximation of experimental data.

Figure 2.

Far UV CD spectra of monomer and amyloid of ApoMb V10F at various urea concentrations, mentioned at the figures (a-d), normalized unfolding transitions of monomer (e) and amyloid (f). Solid lines (e,f) are the result of sigmoidal approximation of experimental data.

Figure 3.

Amyloid unfolding for ApoMb and its mutant variants.

Figure 3.

Amyloid unfolding for ApoMb and its mutant variants.

Figure 4.

Dependence of midpoints of CD denaturation transitions of ApoMb amyloids ([urea]1/2β-U) on the fractions of the native state (fN) under conditions appropriate for aggregation (a), on the changes in hydrophobicity as a result of mutation (b), and on the position of amino acid substitution (c).

Figure 4.

Dependence of midpoints of CD denaturation transitions of ApoMb amyloids ([urea]1/2β-U) on the fractions of the native state (fN) under conditions appropriate for aggregation (a), on the changes in hydrophobicity as a result of mutation (b), and on the position of amino acid substitution (c).

Figure 5.

Electrophoregram of ApoMb V10F amyloid solutions after their incubation at various concentrations of urea (a); total intensity of the lanes (b); fractions of amyloid (fAm), intermediate aggregates (fAgr), and monomeric protein (fМ), as a function of urea concentrations (c), fraction of unfolded protein (fU), as a function of urea concentrations (d), supposed model of amyloids unfolding, where Amβ – amyloid with cross-β-structure, AmI – intermediate aggregates of molecular weight higher 1MDa and without cross-β-structure, Agr – intermediate aggregate of 1 MDa, MU – unfolded monomer (e).

Figure 5.

Electrophoregram of ApoMb V10F amyloid solutions after their incubation at various concentrations of urea (a); total intensity of the lanes (b); fractions of amyloid (fAm), intermediate aggregates (fAgr), and monomeric protein (fМ), as a function of urea concentrations (c), fraction of unfolded protein (fU), as a function of urea concentrations (d), supposed model of amyloids unfolding, where Amβ – amyloid with cross-β-structure, AmI – intermediate aggregates of molecular weight higher 1MDa and without cross-β-structure, Agr – intermediate aggregate of 1 MDa, MU – unfolded monomer (e).

Figure 6.

Dependence of the fractions of amyloids (a), aggregates (b) and monomeric proteins (c) for ApoMb and its mutant variants on urea concentration; molecular weights (MW) for protein markers and the lanes of V10F and L115F ApoMb variants amyloid in 8M urea (d).

Figure 6.

Dependence of the fractions of amyloids (a), aggregates (b) and monomeric proteins (c) for ApoMb and its mutant variants on urea concentration; molecular weights (MW) for protein markers and the lanes of V10F and L115F ApoMb variants amyloid in 8M urea (d).

Figure 7.

Dependence of midpoints of the amyloids (a) and aggregates (b) dissociation on the positions of the amino acid substitutions.

Figure 7.

Dependence of midpoints of the amyloids (a) and aggregates (b) dissociation on the positions of the amino acid substitutions.

Table 1.

Characterization of the stability of monomers and aggregates of ApoMb and its mutant variants.

Table 1.

Characterization of the stability of monomers and aggregates of ApoMb and its mutant variants.

| ApoMb variant |

[urea]1/2β-U

(M) |

fN (%)

data from [31] |

∆hydrophobicity (kcal/mol)

Octanol/water fraction, data from [34] |

[urea]1/2Am-Agr (M) |

[urea]1/2Agr-M (M) |

| WT |

3.9 ± 0.06 |

83.4 ± 0.6 |

0 |

5.2 ± 0.3 |

6.0 ± 0.4 |

| V10A |

3.0 ± 0.09 |

81.8 ± 0.9 |

-1.2 |

4.2 ± 0.1 |

4.8 ± 0.2 |

| V10F |

3.4 ± 0.06 |

74.7 ± 0.6 |

0.8 |

4.7 ± 0.2 |

5.8 ± 0.1 |

| L115A |

2.9 ± 0.07 |

63.8 ± 0.8 |

-1.9 |

4.4 ± 0.1 |

5.6 ± 0.2 |

| L115F |

3.4 ± 0.08 |

74.9 ± 2.1 |

0.1 |

5.5 ± 0.2 |

5.7 ± 0.2 |

| M131A |

2.7± 0.05 |

56.5 ± 2.4 |

-1.2 |

4.1 ± 0.2 |

4.8 ± 0.1 |

| M131W |

3.0 ± 0.04 |

87.9 ± 1.7 |

1.4 |

4.6 ± 0.2 |

5.1 ± 0.1 |

Table 2.

The difference between the amyloids and aggregates stability for mutant variants with substitution in the same positions examined.

Table 2.

The difference between the amyloids and aggregates stability for mutant variants with substitution in the same positions examined.

| Position of substitution |

∆[urea]1/2β-U

(M) |

∆[urea]1/2Am-Agr

(M) |

∆[urea]1/2Agr-M

(M) |

| V10 |

0.4 ± 0.2 |

0.5 ± 0.3 |

0.9 ± 0.3 |

| L115 |

0.5 ± 0.2 |

1.0 ± 0.3 |

0.2 ± 0.2 |

| M131 |

0.3 ± 0.2 |

0.5 ± 0.4 |

0.3 ± 0.2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).