1. Introduction

The endosymbiotic organelles of eukaryotic cells, plastids and mitochondria, are tightly integrated into cellular signaling networks as inseparable parts of the plant cell needed for photosynthesis and ATP production [

1]. The coordinated expression of the organellar and nuclear genomes is achieved by a variety of signals, among which phytohormones make essential contributions. The effects of various hormones on the expression of chloroplast genes are well documented. Exogenously supplied methyl jasmonate (MJ), IAA, ABA and gibberellic acid (GA) repressed the transcription and transcript accumulation of plastid genes, while cytokinins (CKs) counteracted their action [

2]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the transduction of hormonal signals to plastids are still poorly understood. Despite the fact that chloroplasts are sites for the production of a number of hormones or their precursors (CK, ABA, SA, IAA, jasmonic acid and ethylene) [

3], the plastid genome does not retain the genes responsible for the perception and transduction of hormonal signals. Therefore, all stages in the hormone-dependent expression of plastid genes are determined primarily by anterograde signals coming from the nucleus.

Research into interactions between phytohormones and mitochondria has mainly focused on stress-related aspects [

4], and despite some progress, the mechanisms of such interactions are far from being fully understood. The Arabidopsis mitochondrial genome contains 58 genes encoding tRNAs, rRNAs, ribosomal proteins and subunits of the respiratory chain, in addition to 42 noncoding genes [

1]. They are transcribed by two nuclear-encoded page-type RNA polymerases: RPOTm, which is exclusively targeted to mitochondria, and RPOTmp, which is found only in dicots and is bidirected to mitochondria and chloroplasts. RPOTm is vital for plant development, as its

disruption was found to be lethal [

5]. RPOTmp is needed to optimally transcribe a subset of mitochondrial genes, including those for respiratory chain complexes I and IV [

5]. Lack of this enzyme causes mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in a strongly reduced mitochondrial respiratory chain and a compensatory upregulation of alternative oxidase (AOX)-dependent respiration. In addition to functions in mitochondria, RPOTmp was shown to

transcribe the rrn operon from the PC promoter in plastids during seed imbibition [

6]

.

The effects of hormones on organellar gene expression (OGE) can at least partially be transduced through the genes for transcription machinery. In our previous works, we showed that CK-induced changes in the expression of genes encoding chloroplast RNA polymerases and polymerase-associated proteins (PAPs) resulted in modulated expression of chloroplast genes, suggesting a role for the transcription apparatus in their hormone-dependent regulation [

7,

8], However, the exact way in which components of the transcription apparatus induce or suppress the transcription of plastid genes is not known. Hormone-related shifts can also be regulated by organellar-specific import of transcription factors, providing direct binding to transcription initiation sites and conferring promoter specificity in organellar transcription. To date, a convincing example has been presented for ABA-dependent transcription of the chloroplast

psbD gene from the blue light responsive promoter (

BLRP)

via ABA-dependent stimulation of SIG5–PEP-dependent transcription [

9].

Among OGE regulators affected by hormones (bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi) are proteins of the mitochondrial transcription termination factor family (mTERF) and tetra- and pentatricopeptide repeat proteins (TPR and PPRs), which are coexpressed with

mTERF genes of the mitochondrial cluster [

10], 2012). Another potential candidate is a mitochondrial SWI/SNF (nucleosome remodelling) complex B protein, SWIB5, which is capable of associating with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and influencing mtDNA architecture in

Arabidopsis thaliana [

11]. Whether these regulatory proteins are engaged in the transduction of hormonal signals to mitochondria and directing the expression of mt genes remains to be seen.

Accumulating data suggest that in addition to anterograde signaling, the coordinated expression of organellar and nuclear genomes can be achieved through mechanisms of hormone-dependent retrograde signaling. In particular, Wang and Auwerx [

4] established that proteotoxic stress in mitochondria caused by the accumulation of unassembled or unfolded proteins culminates in a systemic hormone response mainly reliant on ethylene signaling but also involving auxin and jasmonate. Blocking ethylene signaling partially repressed mitochondria-to-nucleus signaling, most likely independently of the transcription factor ANAC017, a key regulator of mitochondrial proteotoxic stress responses in plants [

12]. Contrary to these data, Meridino et al [

1] showed that a mutation in

RPOTmp that caused defects similar to the triple response in the dark needed ANAC017. These contradictory results are explained as a result of a weak positive feedback loop linking ethylene and ANAC017-dependent regulation of mitochondrial retrograde signaling. Anyway, these data indicate that hormones are integral factors in regulating the coordinated expression of the organellar and nuclear genomes. However, there is only limited information regarding their exact functions in this process.

In this work, we found that inputs from multiple hormones may cause context-dependent alterations in transcript accumulation of genes for mt RNA polymerases as well as MTERF and SWIB family genes, which play a role in modulating expression changes of mt genes.

2. Results

2.1. Plant hormones trigger alterations in mitochondrial transcript abundance

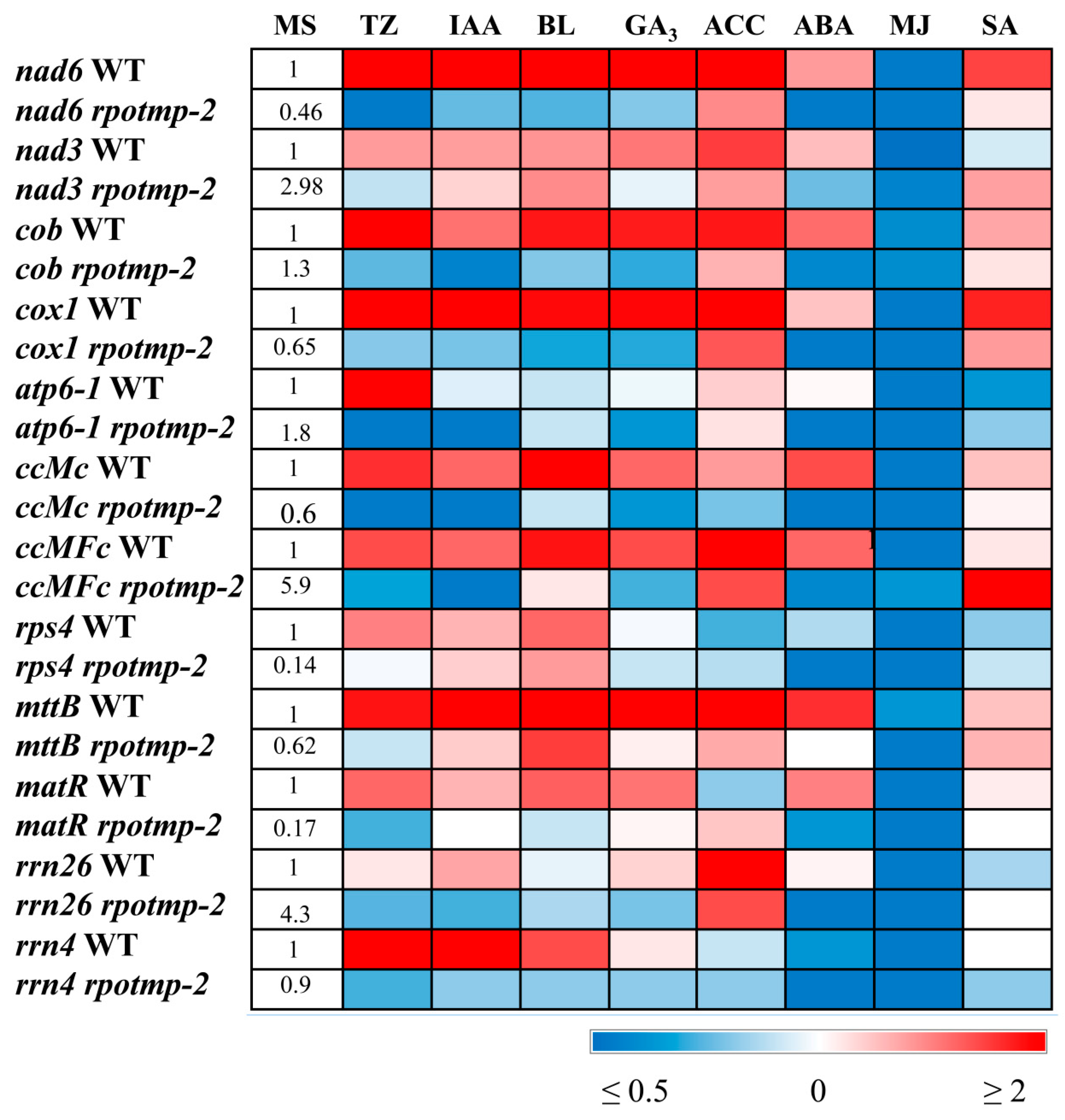

Changes in the expression of nuclear-encoded RNA polymerases (NEP) through direct promoter-binding interactions with hormone-dependent transcription factors may affect the transcription of mitochondrial genes. To test the putative role of RPOTmp in hormone-dependent mitochondrial transcription, we first analysed the accumulation of mitochondrial transcripts in Columbia 0 and RPOTmp-deficient rpotmp-2. Twelve genes were selected for the analysis, which represent the main functional groups of the mitochondrial genome. The analysis included genes for subunits of complexes I (nad3 and nad6), III (cob), IV (cox1) and V (atp6-1) of the electron transport chain, genes for cytochrome C biogenesis (ccmC and ccmFc), ribosomal and transport proteins (rps4 and mttB), rRNA (rrn26), and the maturase gene (matR).

Some of the selected genes (

nad6, cox1, ccmC, mttB), rps4, matR) are preferentially transcribed by RPOTmp, and their transcription levels were reduced in

rpotmp-2 (

Figure 1,

Table S1)

, which is consistent with the data of Kuhn et al. [

5]. Steady-state levels of some RPOTmp-independent transcripts (

rnn26,

ccMFc, nad3) were even enhanced in the absence of RPOTmp. These alterations are thought to be associated with elevated levels of cellular mtDNA caused by general energy constraints in the mutant [

5].

To address hormone-induced changes, we performed qRT‒PCR analysis. Differentially expressed genes with a ratio of transcript change of 1.5 in at least two tests were classified as regulated [

13]. According to the results obtained, all selected mitochondria-encoded genes were strongly repressed by MJ and induced by CK (except for

rrn26) in wild-type (WT) seedlings (

Figure 1,

Table S1). The response to other hormones was gene specific, with certain mt genes exhibiting expression shifts, but others remaining unaltered. Thus,

cox1 and

nad6 displayed a 2-fold increase in transcript abundance following BL, IAA, ACC, GA

3 and SA treatments, while none of these hormones affected

atp6 expression. The

rrn4 gene was upregulated by BL and IAA, but induction was not observed in response to ACC, GA

3 and SA. In this regard, it should be noted that some hormone responses may be near saturation due to optimal endogenous concentrations.

Another potential complication in assessing the sensitivity of mt-encoded genes to hormones is associated with the phases of ontogenesis. Depending on the age of a plant, gene expression changes resulting in either an increase or decrease in transcript levels can be triggered by the same treatment. Thus, the expression of mt-encoded genes sharply decreased when wild-type seedlings were grown in the dark for 4 days on medium containing

trans-zeatin (TZ, 1 µM) compared with seedlings cultivated on medium without hormone (

Table S2). Hence, the changes in mt gene expression in response to hormonal treatment may represent the outcome of completely different effects, reflecting opposite pathways of their regulation.

2.2. Disruption of RPOTmp alters sensitivity to hormone treatment

Shifts in the transcript abundance of mt-encoded genes were abolished in

the rpotmp-2 background following hormone treatment, with the exception of BL-induced accumulation of

mttB matrices (

Figure 1). Moreover, several genes that were upregulated in WT were even repressed in

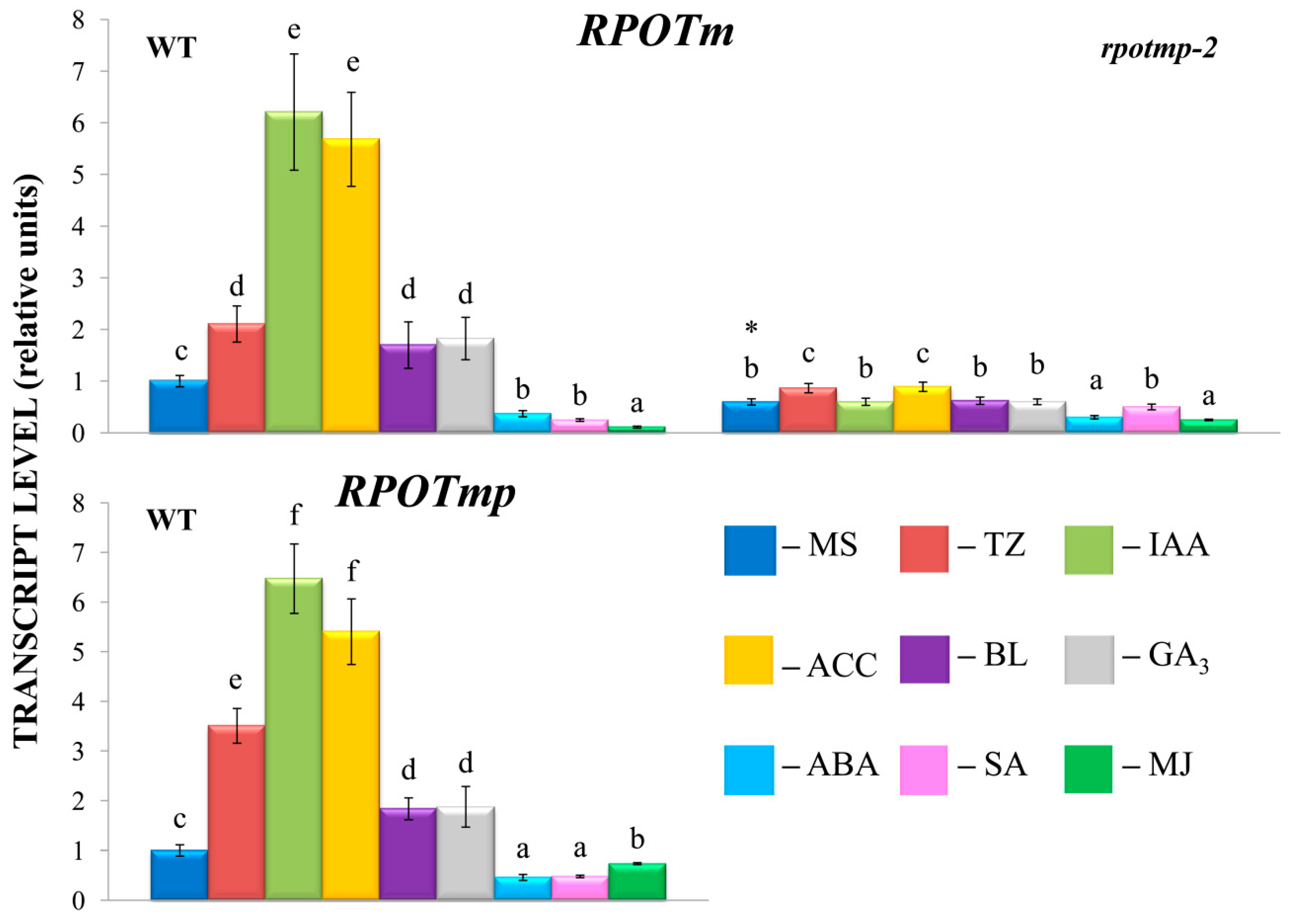

rpotmp-2. It thus appears that the loss of RPOTmp blocks or attenuates hormone-dependent responses of mt-encoded genes. Strikingly, similar responses were observed for both RPOTmp-dependent and RPOTmp-independent genes when the magnitude of their fluctuations in the mutant was assessed relative to basal values. Moreover, such a response was also found for hormones, the corresponding regulatory elements of which were absent in the promoters of mt polymerases. These results suggest that the modulation in mt gene regulation may be the result of an altered hormonal status of

rpotmp-2. The changes may also reflect modified expression in the mutant of the second mitochondrial polymerase RPOTm, which is the only active one in the

rpotmp-2 mitochondria, since hormone-related changes in

RPOTm transcript levels were mitigated in the

rpotmp background (

Figure 2).

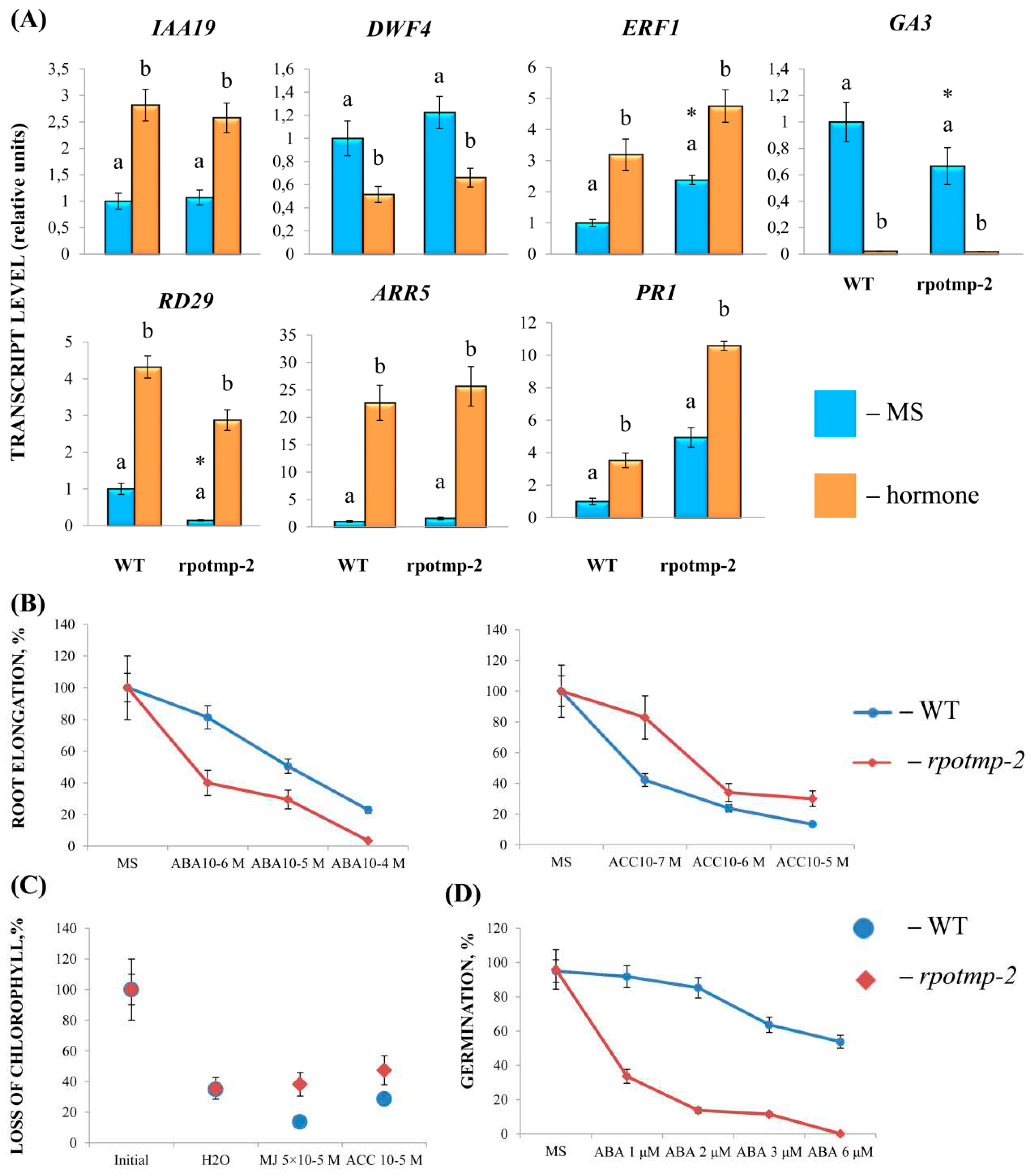

To experimentally evaluate the sensitivity of

rpotmp-2 to hormone treatment, we first examined hormone reporters. The mutant and WT had similar levels of the auxin marker

IAA19 and BS marker

DWF4 in 2-week-old seedlings. At the same time, the mutant exhibited elevated steady-state expression values of ethylene and the MJ marker

ERF1. In parallel, the

rpotmp-2 mutant was less sensitive to ACC in root elongation and dark detached assays than Col0 (

Figure 3). We further found that mutant leaves were less sensitive to MJ in the dark detached leaf assay, consistent with a higher transcript abundance of the MJ marker gene

ERF1 (

Figure 3). In contrast, the expression levels of the ABA reporter RD29 were reduced in

rpotmp-2 and were upregulated by the hormone two times higher than those in the wild type. The mutant was more sensitive to ABA treatment in the root elongation assay, especially in germination tests (

Figure 3), and had expectedly reduced levels of the gibberellic acid synthesis gene

GA3.

In addition, we found that the mutant exhibited higher expression levels of the CK marker gene

ARR5 and SA reporter

PR1, suggesting a possibly elevated content of corresponding hormones. However, there were no significant differences in their responses to CK and SA treatments in physiological tests (

Figure 3).

In summary, it can be concluded that disruption of RPOTmp may alter the hormonal status of the mutant and its response to treatment with exogenous hormones. Furthermore, the changes in mt transcript levels in the mutant background may be the result of multifactor events, when impaired RPOTmp function and altered hormonal metabolism are superimposed on the modified RPOTm activity and, possibly, on the activity of additional transcription factors that bind directly to promoter regions of mitochondrial genes.

2.3. The RPOTmp promoter has potential cis-regulatory elements that respond to phytohormones

In silico analysis highlighted a number of consensus sequences in the 1.2 kb promoter region upstream of the RPOTmp coding sequence recognized by potential

cis-regulatory elements (CREs) that may be involved in the response to phytohormones. The most significant differences are listed in

Table 1. Putative motifs at positions –297/–287 bp and –1081/–1073 bp (AGATCCTC) and –966/–958 bp (AAAGATTCGA) relative to ATG (

Figure S1) are well aligned with the consensus sequence 5'-(AGATHY, H(a/t/c), Y(t/c))-3' [

14] for cytokinin-sensitive type B response regulators (ARR-B) in a direct strand. Reverse complement sequences of ARR-B (TCGAATCTTT and GAGGATCTTA) were also found.

Two to four putative auxin-responsive elements (AuxRE) were predicted within the

RpoTmp promoter. However, only two of them, GGGTCGGGTA for ARF3 at position –305/–315 bp in the direct strand and T

CAGACAAAA for ARF5 at –799/–808 bp in the complementary strand, contained the canonical motif AuxREs 5'-(TGTCNC, N(a/t/c/g))-3' for auxin-responsive factor (ARF) [

15].

We did not detect the classical G-box with ABA-responsive elements: ABRE 5'-((c/g/t)ACGTG(g/t)(a/c))-3' and coupling element 3 (CE3) ACGCGTGTC), characteristic of ABA-regulated genes. At the same time, a 1.2-kb region of

RPOTmp pro is abundant with

cis-regulatory elements for ABA-regulated genes, including MYB (5'-c/tAACNA/G)-3'), MYC (5'-CANNTG-3'), WRKY (5'-(T)(T)TGAC(C/T)-3') and RAV (5'-CAACA-3'; 5'-CACCTG-3') family transcription factors (

Table 1) [

16]. In parallel, the DPBF1&2 binding site motif at –923/–927 bp (ACACCTG) in a complementary strand could be indirectly responsible for the reactions to ABA treatment [

17].

The 5'UTR of

RPOTmp pro also contains various CREs (

Figure S1). including AuxRE, two sequences specific for REF6 (RELATIVE OF ELF6) with the consensus motif 5'-CTCTGYTY-3', which may play a role in ethylene and brassinosteroid signaling, and ethylene response elements (EREs) or GCC boxes with the 5'-GCCGCCGCC-3' core sequence [

18].

In addition, cross-regulation of

RPOTmp gene expression by different phytohormones can be achieved by numerous MYB or MYB-related factors even in the absence of characteristic CREs (

Table S3).

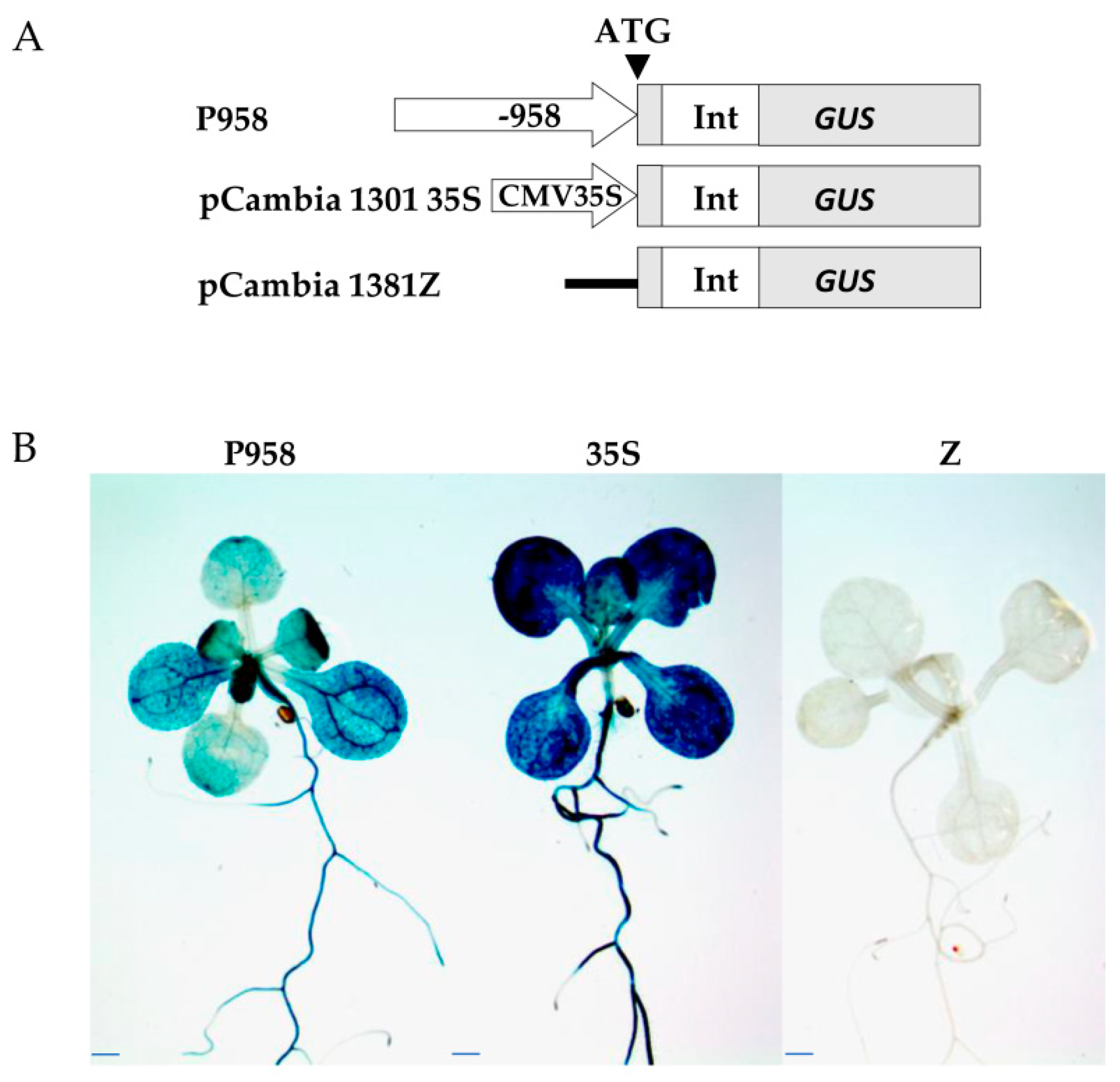

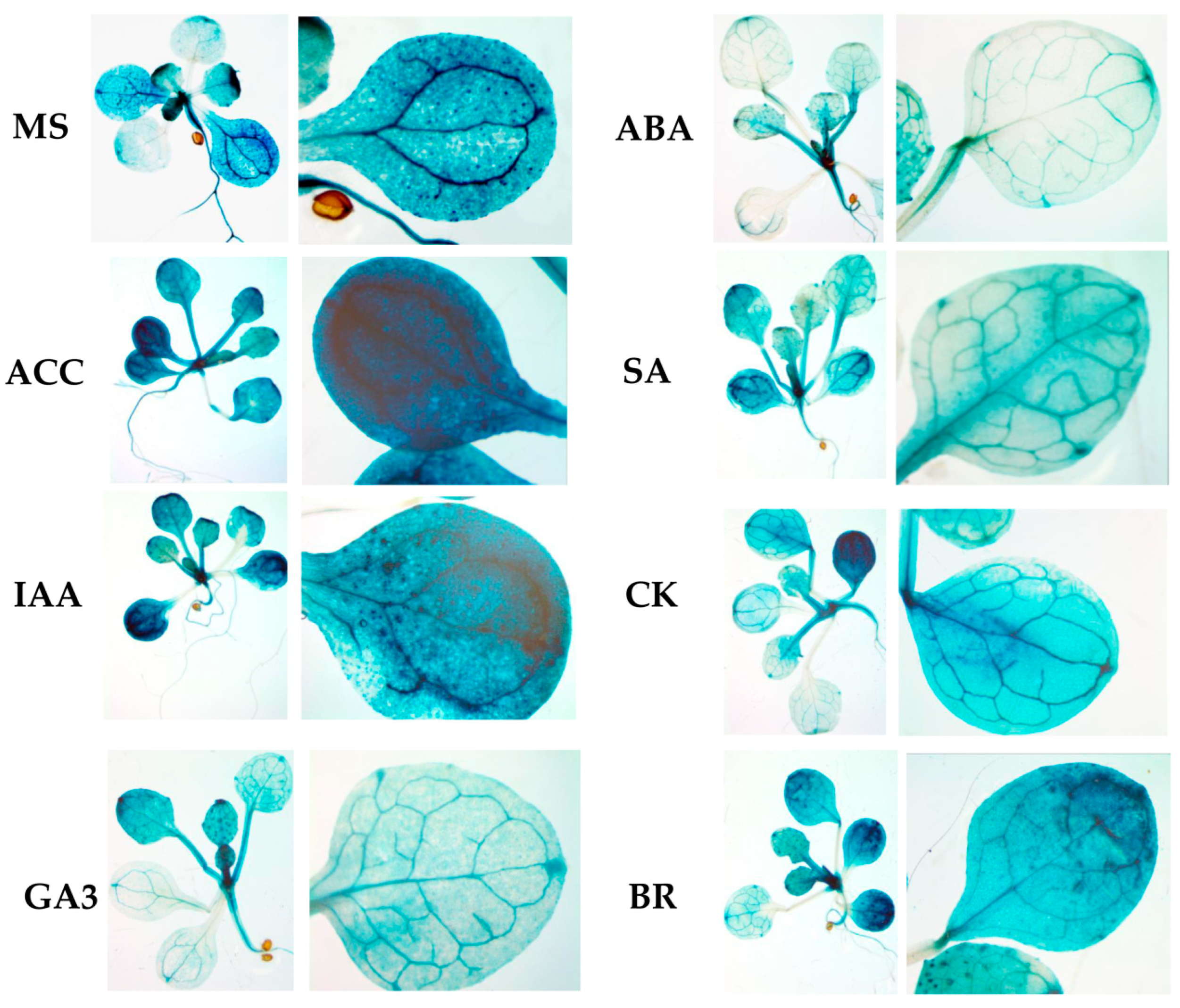

2.4. Hormone treatments induce changes in GUS expression in the RPOmp::GUS reporter strain

To assess the functional properties of the identified motifs, a genetic construct based on the pCAMBIA1381z vector containing a 5'-deletion fragment (–958 bp) upstream of the start codon of

RPOTmp was fused to the open reading frame of the β-glucuronidase reporter gene and used to generate the

RPOTmp pro::GUS line (

Figure 4A). β-Glucuronidase staining of 10-day-old seedlings of transgenic P958 (T2 and T3 generations) grown on half MS showed stable blue colouration in the vascular tissues of roots, cotyledons and primary leaves as a result of

RPOTmp pro::GUS expression (

Figure 4B), while plants expressing the reporter GUS gene without a promoter remained virtually unchanged.

To examine whether the expression patterns of the construct change in a hormone-dependent manner, 10-day-old plants were treated with solutions of hormones for 24 hours at 22°C under a 16-h light regime, and GUS staining was performed. Plants expressing GUS activity under the 35S CAMV promoter were used as a positive control, whereas plants expressing the reporter GUS gene without a promoter were used as a negative control (

Figure 5).

We found that GUS staining was obviously darker after ACC and IAA treatment in plants containing the -958 bp fragment than in the control samples. There were also no pronounced differences from the control variants when the reporter strain was treated with CK, GA, BL or SA. In parallel, the signal decreased when the seedlings containing the 958 bp fragment were exposed to ABA. From these observations, we conclude that the -958 bp promoter fragment of the RPOTmp gene is functionally involved in responses to IAA, ACC, and ABA.

GUS activity in the

RPOTmp::GUS reporter strain only partially corresponded to

RPOTmp transcript abundance under hormone treatment of WT plants. According to our qRT‒PCR tests,

RPOTmp, as well as

RPOTm, were reproducibly induced by CK, IAA, ACC, and BL and downregulated by ABA in WT plants (

Figure 2). They were also downregulated by SA, although no reliable changes in GUS activity were observed when

RPOmp::GUS reporter strains were treated with these hormones.

We therefore conclude that changes in the expression of RPOTmp may affect the transcription of mitochondrial genes both directly through promoter-binding interactions with hormone-dependent transcription factors and indirectly.

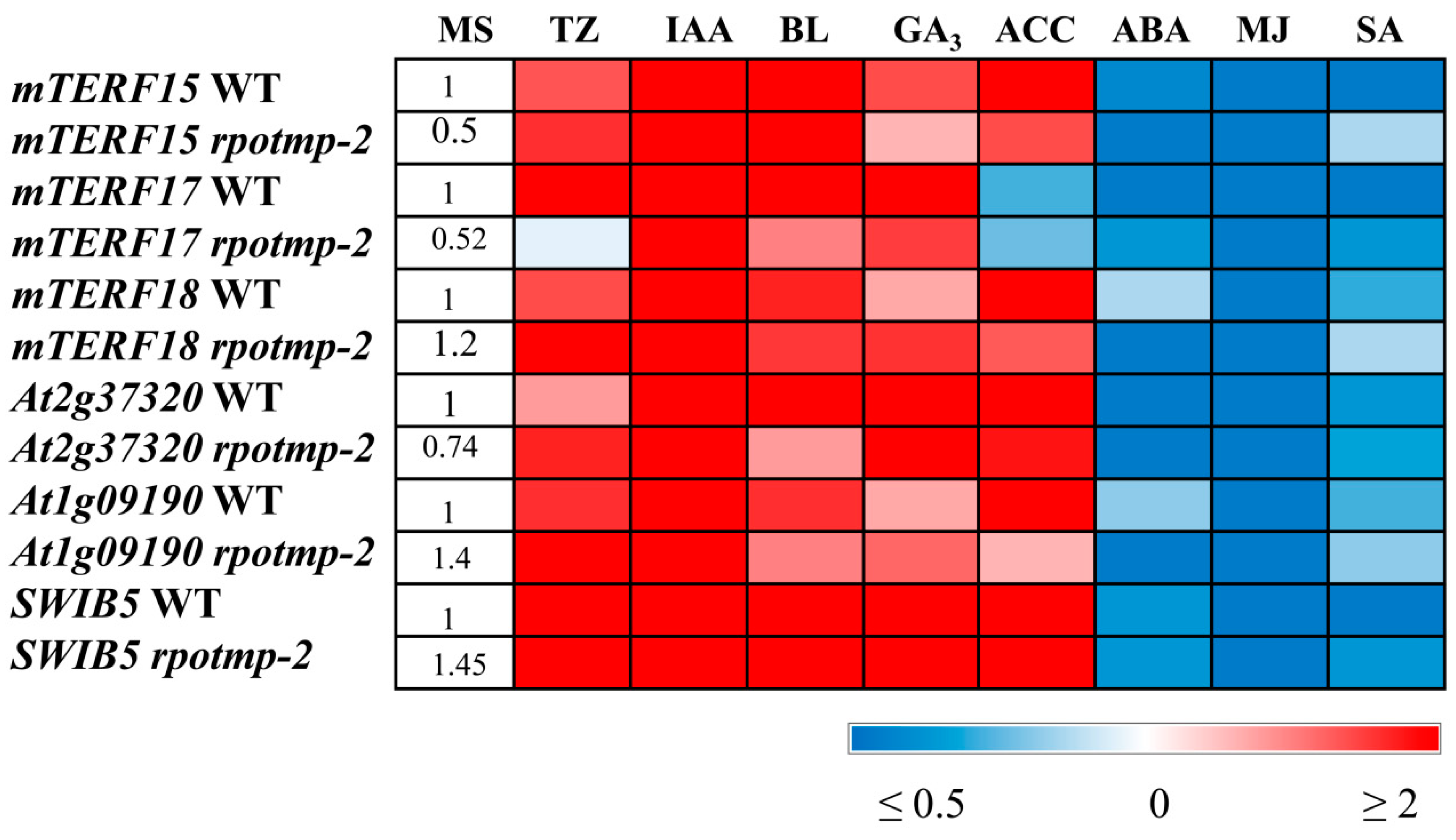

2.5. Exogenous hormone treatment modulated the MTERF and SWIB family genes

Hormone-related shifts in the expression of organellar genes can also be induced by organellar-specific transcription factors

via direct binding to transcription initiation sites of mt genes. Proteomic studies revealed the presence of a large number of proteins containing DNA-binding motifs in plant mitochondria, which are expected to play key roles in mtDNA expression [

19]. Some of these factors may represent facilities for hormonal regulation of mt gene expression. Among them is a diversified mTERF family that includes 35 members targeted to chloroplasts and/or mitochondria, where they have been shown to function in OGE at the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level [

20]. Although the members of the “mitochondrial” and “mitochondrion-associated” clusters respond weakly to physiological perturbations [

10], at least some of them were up- or downregulated more than 2-fold in response to exogeneous hormones according to the microarray data provided on the resource server (

http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi).

To test whether they could represent instruments for the transduction of hormonal signals to mitochondria, we focused on mTERF15,17 and 18 since their promoter regions are predicted to possess binding site motifs for hormone-regulated transcription factors (

https://agris-knowledgebase.org). mTERF15, with an experimentally confirmed function, is naturally induced during germination [

10] and is needed for

nad2 intron 3 splicing [

21]. Its dysfunction disrupts formation and decreases its activity of complex I. MTERF18 transcript levels were shown to fall upon exposure to heat and during germination [

10].

In 10-day-old light-grown seedlings, transcripts of all three genes of interest increased in abundance by 2-4-fold in response to IAA or CK and decreased by approximately 2-5 times after treatment with ABA, SA, and MJ. This finding correlates well with the data obtained for RPOTm and RPOTmp and with hormone-mediated expression of mt-encoded genes. It is worth noting that while mTERF15 and 18 were upregulated by ACC, mTERF17 was even slightly repressed. A unique response of mTERF17 was also observed in etiolated seedlings grown on medium containing CK: While its expression was upregulated, the expression of mTERF15 and 18 was suppressed in accordance with the repressive regulation of mt-encoded genes by cytokinin in this experimental setup. These results suggest that members of the mTERF family may have overlapping but also specific functions in hormone-mediated regulation of mt-encoded genes depending on development status and/or environmental conditions.

The effects of hormonal application could also be regulated through tetra- and pentatricopeptide repeat proteins (TPR and PPR) targeted to mitochondria and coexpressed with mTERFs of the mitochondrial cluster. We have shown that two such genes,

At1g09190 and

At2g37320, encoding TPR-like superfamily proteins, followed

mTERF15 and

mTERF18 in their hormone-mediated expression patterns (

Figure 6,

Table S1) and corresponded to the expression patterns of some mt-encoded genes.

In addition, modulations in the expression of mt-encoded genes could be attributed to the activity of the mitochondrial nucleoid-associated protein SWIB5, a member of the SWIB (ATP-dependent multisubunit switch/sucrose nonfermentable multiprotein complex B) family, which is implicated in DNA binding and remodelling. SWIB5 associates with mtDNA and participates in the regulation of mitochondrial gene expression [

11](Blomme et al, 2017). According to our tests, the relative expression values of

SWIB5 were increased by 3-10-fold after CK, ACC and IAA application and nearly 6-fold following BL and GA

3 treatment (

Figure 6). Interestingly, the response of mTERF genes and the genes for mt RNA polymerases to the last two hormones was considerably weaker and barely exceeded 1.5 times, despite significant induction of some mt-encoded genes.

As expected, stress-related hormones (ABA, MJ and SA) downregulated all aforementioned nuclear genes. However, it is worth noting that several mt-encoded genes (nad6, mttB, matR, cob and ccMc) were significantly activated by ABA treatment, suggesting the involvement of alternative regulatory pathways.

In summary, these data indicate a function for MTERF and coexpressing TPR proteins in hormone-regulated expression of mt-encoded genes in addition to organelle RNA polymerases and mitochondrial nucleoid-associated proteins.

3. Discussion

In general, the results obtained indicate that the hormone-mediated responses of mt genes in Arabidopsis seedlings can be attributed to the activity of mitochondrial RNA polymerases able to bind hormone-dependent transcription factors and, possibly, to supplementary transcription factors that can bind directly to the promoter regions of mitochondrial genes. This assumption is at least partially supported by hormone-induced changes in GUS expression in the

RPOmp::GUS reporter strain and coordinated transcription responses of

RPOTmp and/or

RPOTm with some mitochondrial-encoded genes following hormone treatment. The most regular fluctuations occurred upon treatment with CK and MJ, which promoted up- or downregulation of all tested mt genes in a context-specific manner. The responses of selected mt genes to other hormones were gene-specific and did not always follow the expression patterns of RNA polymerase genes, consistent with the idea that nuclear and mitochondrial transcription may be independently regulated [

22].

In particular, side-by-side comparison showed that downregulation of

RPOTmp by ABA corresponded to upregulation of a number of mt genes, including

nad6, cob, ccMc, ccMfc and

mttB (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Enhanced mitochondrial activity induced by ABA treatment may be a consequence of increased energy consumption in response to stressful situations, which are usually accompanied by an increase in ABA levels. Growth effects documented for

RPOTmp transcripts following IAA treatment were not observed for

atp6 or

rnn 26, although the expression of other selected mt genes was significantly increased. This specificity could provide a means to fine-tune the activity of certain genes in response to multiple challenges.

While our tests clearly linked CK-induced changes in

RPOTmp and

RPOTm transcript abundance to the modulations of mt-encoded gene expression, there was one unexpected finding. GUS activity in

RPOmp::GUS reporter strains showed no changes following CK treatment, contrary to the upregulation of

RPOTmp transcript abundance. Such results clearly contradicted the presence of putative CK-regulated

cis-elements in

the RPOTmp promoter, as predicted by bioinformatic resources. It should be noted, however, that the accessibility of such binding sites is doubted by ChiP studies of Zubo et al. [

23] and Xie et al. [

14], who found no binding locations for type B ARRs in

the RPOTmp promoter. Overall, these data indicate that CK-dependent regulation of

RPOTmp may be indirect.

In addition to mt RNA polymerases, transcription factors directly binding to the promoter regions of mitochondrial genes could be implicated in mediating phytohormone signals to mt genes. Among them, the genes of the mTERF family and the genes for tetra- and pentatricopeptide repeat proteins (TPR and PPRs) coexpressed with

mTERF genes are of particular interest since they are regulated by hormone treatment and are capable of binding nucleic acids [

20]. In our tests, MTERF and TPR protein genes specifically responded to hormone treatment, displaying both negative and positive regulation in a context-dependent manner. According to bioinformatic resources, the promoter regions of these genes possess putative

cis-acting elements involved in responses to a number of phytohormones, including ABF, ABRE, GATA, W-box, etc. (Agris). However, additional experiments are needed to confirm physical interactions between MTERFs and hormone-induced TFs. Of note, mTERF17 and 18 have been shown to bind type B response regulators ARR12 and ARR1,10 and 12, respectively [

14], thus presenting direct targets for cytokinin signaling.

Binding motifs for ARR1 and 10 were also revealed in the promoter region of

SWIB5 [

14,

23]. In our experiments, this gene was strongly upregulated by CK in light-grown seedlings and downregulated in etiolated seedlings grown on СK-containing medium in the dark, which was consistent with the changes in transcript abundances of selected mt-encoded genes. The protein encoded by

SWIB5 belongs to the nucleosome remodelling complex of mitochondria, similar to the bacterial nucleoid. It is essential for cell proliferation and stress responses and is believed to adjust the accessibility of mtDNA for RNA polymerases, linking hormone responses with chromatin remodelling [

24]. SWIB5OE displayed a significant downregulation of

CRF6 (CYTOKININ RESPONSE FACTOR6) [

11], encoding a cytokinin responsive AP2/ERF transcription factor that plays a key role in the inhibition of dark-induced senescence and oxidative stress as a negative regulator of the CK-associated module. [

25]. Furthermore, CRF6 refers to a stimulator of mitochondrial dysfunction (MDS) induced by mitochondrial perturbation. Since both cellular proliferation and stress responses are associated with CK-mediated modulations, we suggest that CK-dependent regulation of SWIB5 may be one of the mechanisms underlying the expression of mitochondrial genes. Additionally, the involvement of SWIB5 in responses to several other plant hormones suggests pleiotropic functions in the regulation of the mt genome. However, this suggestion must be further addressed in future experiments.

Since any biological function is usually implemented by several independent mechanisms, both organelle RNA polymerases and mitochondrial transcription factors, as well as mitochondrial nucleoid-associated proteins acting redundantly, can be direct targets for hormone-regulated transcription factors. They can form a core regulatory module that acts in the direct transduction of hormonal signals to mitochondria. Alternatively, hormone-related transcriptional activity of these genes may be modulated indirectly, suggesting that additional factors are needed for their regulation. This is especially relevant for brassinosteroids, since the promoters of RPOTmp (and of selected genes for mTERF and PPR proteins) do not contain consensus binding sites for BS-induced transcription factors BZR and BES.

Strikingly, upregulation of mt genes by BS (except for

mttB) was dampened in the

rpotmp-2 background in the same way as for hormones whose transcription factors can directly interact with the

RPOTmp promoter. Therefore, loss of RPOTmp has far-reaching implications for the activity of hormone-related genes. According to the data of Meredino et al. [

1], impaired function of RPOTmp caused changes reminiscent of the triple response of seedlings exposed to ethylene and could therefore contain increased levels of ethylene. In accord with extensive crosstalk and signal integration among growth-regulating hormones, plants with reduced or increased content of one hormone can show altered responses to another [

26]. Thus,

rpotmp exhibited increased steady-state levels of transcripts for the CK marker gene ARR5, as well as elevated transcript accumulation of the CK synthesis genes

IPT3 and

IPT5 and a reduced level of hormone catabolism gene

CKX3 expression, which implies a possible increase in the content of endogenous cytokinins [

27]

. In parallel, the expression of reporter genes for GA (

GA3) and SA (

PR1) was changed in the

rpotmp compared to WT (

Figure 3). These results suggest that disruption of RPOTmp may induce a hormonal imbalance in concerted hormonal synthesis and signaling and, as a result, a differential mitochondrial response to hormonal treatment. It thus appears that knockout or overexpression of genes regulating organellar proteins can provoke indirect effects that cast doubt on the validity of corresponding mutants in the elucidation of naturally occurring hormone-dependent responses.

On the other hand, a change in the hormonal status of the

rpotmp mutant may be a consequence of retrograde signaling from dysfunctional mitochondria. It has been suggested that ethylene boosts mitochondrial respiration and restores mitochondrial function upon mitochondrial proteotoxic stress (mitochondrial unfolded protein response) as the anterograde arm of a feedback loop [

4]. This was accompanied by MAPK6 activation and an increase in the transcription of the ethylene synthesis gene

ACS6. Similarly, altered ethylene levels in the

rpotmp mutant may be a means to recover mitochondrial functionality under reduced levels of respiratory complexes I and IV.

Other hormone responses to mitochondrial proteotoxic stress included the induction of auxin, ABA, and jasmonate signaling; a decrease in cytokinin signaling; and unchanged salicylic acid signaling [

4]. Notably, in line with these results, detached

rpotmp leaves were more resistant to MJ treatment (

Figure 3C), suggesting increased steady-state levels of this hormone in the case of mitochondrial dysfunction.

The role of auxin is especially significant. Two independent works revealed that mitochondrial stress stimuli caused a suppression of auxin signaling, and conversely, auxin treatment repressed mitochondrial stress [

28,

29]. According to the results of our analyses, ethylene and IAA reproducibly induced transcript accumulation of

RPOTmp and RPOTmp::GUS fusion activity, which correlated with the enhanced levels of mitochondrial RNAs. This implies a direct signaling interaction between these two hormones and RNA polymerase in the transduction of hormone operational signals from nuclei to mitochondria.

In general, the results of the study indicate that hormones are essential mediators that regulate mitochondrial gene expression in a context-dependent manner. Inputs from multiple hormones саn cause/induce alterations in transcript accumulation of mt-related nuclear genes, which in turn trigger the expression of mt genes.