Submitted:

05 November 2023

Posted:

07 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of Study and Sample Collection

2.2. Outcome Variable: COVID-19 Infection

2.3. Exposure Variables: Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Factors

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Factors and COVID-19 Infection

3.3. Both Models 2 and 3 Adjusted for Dietary Patterns

Vitamin D Supplement Use and COVID-19 Infection

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard Available online:. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Rhodes, A.; Cheng, A.C.; Peacock, S.J.; Prescott, H.C. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA 2020, 324, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, A.; Aslan, C.; Zolbanin, N.M.; Jafari, R. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in COVID-19: Possible Mechanisms and Therapeutic Management. Pneumonia (Nathan) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodin, P. Immune Determinants of COVID-19 Disease Presentation and Severity. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, K.K.; Baker, W.L.; Sobieraj, D.M. Myth Busters: Dietary Supplements and COVID-19. Ann. Pharmacother. 2020, 54, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, F. Vitamin-D and COVID-19: Do Deficient Risk a Poorer Outcome? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, D.A.; Branche, A.R.; Zhang, L.; Graciaa, D.S.; Choudhary, M.; Hatlen, T.J.; Osman, R.; Babu, T.M.; Robinson, S.T.; Gilbert, P.B.; et al. Clinical and Demographic Factors Associated with COVID-19, Severe COVID-19, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Adults: A Secondary Cross-Protocol Analysis of 4 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2323349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maskari, Z.; Al Blushi, A.; Khamis, F.; Al Tai, A.; Al Salmi, I.; Al Harthi, H.; Al Saadi, M.; Al Mughairy, A.; Gutierrez, R.; Al Blushi, Z. Characteristics of Healthcare Workers Infected with COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, R.D.; Sánchez-Soliño, O.; Alami, N.N.; Johnson, C.; Fang, Y.; Wegrzyn, L.R.; Krueger, W.S.; Ye, Y.; Dreyer, N.; Gray, G.C. EpidemiologiCal POpulatioN STudy of SARS-CoV-2 in Lake CounTy, Illinois (CONTACT): Methodology and Baseline Characteristics of a Community-Based Surveillance Study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Diaz, C.E.; Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Mena, L.; Hall, E.; Honermann, B.; Crowley, J.S.; Baral, S.; Prado, G.J.; Marzan-Rodriguez, M.; Beyrer, C.; et al. Risk for COVID-19 Infection and Death among Latinos in the United States: Examining Heterogeneity in Transmission Dynamics. Ann. Epidemiol. 2020, 52, 46–53.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, H.; Talaei, M.; Greenig, M.; Zenner, D.; Symons, J.; Relton, C.; Young, K.S.; Davies, M.R.; Thompson, K.N.; Ashman, J.; et al. Risk Factors for Developing COVID-19: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study (COVIDENCE UK). Thorax 2022, 77, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutikov, M.; Palmer, T.; Tut, G.; Fuller, C.; Shrotri, M.; Williams, H.; Davies, D.; Irwin-Singer, A.; Robson, J.; Hayward, A.; et al. Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection According to Baseline Antibody Status in Staff and Residents of 100 Long-Term Care Facilities (VIVALDI): A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e362–e370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letizia, A.G.; Ge, Y.; Vangeti, S.; Goforth, C.; Weir, D.L.; Kuzmina, N.A.; Balinsky, C.A.; Chen, H.W.; Ewing, D.; Soares-Schanoski, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Seropositivity and Subsequent Infection Risk in Healthy Young Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, S.F.; O’Donnell, D.; Stoesser, N.E.; Matthews, P.C.; Howarth, A.; Hatch, S.B.; Marsden, B.D.; Cox, S.; James, T.; Warren, F.; et al. Antibody Status and Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Health Care Workers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, J.; Joshi, A.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Leeming, E.R.; Mazidi, M.; Drew, D.A.; Gibson, R.; Graham, M.S.; Lo, C.-H.; Capdevila, J.; et al. Diet Quality and Risk and Severity of COVID-19: A Prospective Cohort Study. Gut 2021, 70, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Park, J.-Y.; Lee, H.S.; Suh, J.; Song, J.Y.; Byun, M.K.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, J.-W.; et al. Effect of Asthma and Asthma Medication on the Prognosis of Patients with COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2002226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeuffer, C.; Le Hyaric, C.; Fabacher, T.; Mootien, J.; Dervieux, B.; Ruch, Y.; Hugerot, A.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Pointurier, V.; Clere-Jehl, R.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors Associated with Severe COVID-19: Prospective Analysis of 1,045 Hospitalised Cases in North-Eastern France, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, P.; Murray, B.; Klaser, K.; Graham, M.S.; Mazidi, M.; Leeming, E.R.; Thompson, E.; Bowyer, R.; Drew, D.A.; Nguyen, L.H.; et al. Modest Effects of Dietary Supplements during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from 445 850 Users of the COVID-19 Symptom Study App. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2021, 4, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmati, M.; Fatemi, R.; Yon, D.K.; Lee, S.W.; Koyanagi, A.; Il Shin, J.; Smith, L. The Effect of Adherence to High-quality Dietary Pattern on COVID-19 Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.S.Y.; Fernando, D.I.; Chan, M.Y.; Sia, C.-H. Obesity in COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore 2020, 49, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadayon Najafabadi, B.; Rayner, D.G.; Shokraee, K.; Shokraie, K.; Panahi, P.; Rastgou, P.; Seirafianpour, F.; Momeni Landi, F.; Alinia, P.; Parnianfard, N.; et al. Obesity as an Independent Risk Factor for COVID-19 Severity and Mortality. Cochrane Libr. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wander, P.L.; Lowy, E.; Beste, L.A.; Tulloch-Palomino, L.; Korpak, A.; Peterson, A.C.; Kahn, S.E.; Boyko, E.J. The Incidence of Diabetes among 2,808,106 Veterans with and without Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thani, A.; Fthenou, E.; Paparrodopoulos, S.; Al Marri, A.; Shi, Z.; Qafoud, F.; Afifi, N. Qatar Biobank Cohort Study: Study Design and First Results. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawadi, H.; Akasheh, R.T.; Kerkadi, A.; Haydar, S.; Tayyem, R.; Shi, Z. Validity and Reproducibility of a Food Frequency Questionnaire to Assess Macro and Micro-Nutrient Intake among a Convenience Cohort of Healthy Adult Qataris. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, H.; Chen, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, T. A Review of Statistical Methods for Dietary Pattern Analysis. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lusignan, S.; Dorward, J.; Correa, A.; Jones, N.; Akinyemi, O.; Amirthalingam, G.; Andrews, N.; Byford, R.; Dabrera, G.; Elliot, A.; et al. Risk Factors for SARS-CoV-2 among Patients in the Oxford Royal College of General Practitioners Research and Surveillance Centre Primary Care Network: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paleiron, N.; Mayet, A.; Marbac, V.; Perisse, A.; Barazzutti, H.; Brocq, F.-X.; Janvier, F.; Dautzenberg, B.; Bylicki, O. Impact of Tobacco Smoking on the Risk of COVID-19: A Large Scale Retrospective Cohort Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, D.; Shahab, L.; Brown, J.; Perski, O. The Association of Smoking Status with SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Hospitalization and Mortality from COVID-19: A Living Rapid Evidence Review with Bayesian Meta-Analyses (Version 7). Addiction 2021, 116, 1319–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggi, F.; Rosellini, A.; Spezia, P.G.; Focosi, D.; Macera, L.; Lai, M.; Pistello, M.; de Iure, A.; Tomino, C.; Bonassi, S.; et al. Nicotine Upregulates ACE2 Expression and Increases Competence for SARS-CoV-2 in Human Pneumocytes. ERJ Open Res. 2021, 7, 00713–02020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, Z.; Motlagh Ghoochani, B.F.N.; Hasani Nourian, Y.; Jamalkandi, S.A.; Ghanei, M. The Controversial Effect of Smoking and Nicotine in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindle, H.A.; Newhouse, P.A.; Freiberg, M.S. Beyond Smoking Cessation: Investigating Medicinal Nicotine to Prevent and Treat COVID-19. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22, 1669–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Heidarizadeh, M.; Entesari, M.; Esmailpour, A.; Esmailpour, M.; Moradi, R.; Sakhaee, N.; Doustkhah, E. In Silico Investigation on the Inhibiting Role of Nicotine/Caffeine by Blocking the S Protein of SARS-CoV-2 versus ACE2 Receptor. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsalinos, K.; Eliopoulos, E.; Leonidas, D.D.; Papadopoulos, G.E.; Tzartos, S.; Poulas, K. Nicotinic Cholinergic System and COVID-19: In Silico Identification of an Interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and Nicotinic Receptors with Potential Therapeutic Targeting Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitzke, M. Is the Post-COVID-19 Syndrome a Severe Impairment of Acetylcholine-Orchestrated Neuromodulation That Responds to Nicotine Administration? Bioelectron. Med. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J. COVID-19: Consider Cytokine Storm Syndromes and Immunosuppression. Lancet 2020, 395, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, K.J. The Inflammatory Reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clift, A.K.; von Ende, A.; Tan, P.S.; Sallis, H.M.; Lindson, N.; Coupland, C.A.C.; Munafò, M.R.; Aveyard, P.; Hippisley-Cox, J.; Hopewell, J.C. Smoking and COVID-19 Outcomes: An Observational and Mendelian Randomisation Study Using the UK Biobank Cohort. Thorax 2022, 77, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallus, S.; Scala, M.; Possenti, I.; Jarach, C.M.; Clancy, L.; Fernandez, E.; Gorini, G.; Carreras, G.; Malevolti, M.C.; Commar, A.; et al. The Role of Smoking in COVID-19 Progression: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 220191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilezikian, J.P.; Binkley, N.; De Luca, H.F.; Fassio, A.; Formenti, A.M.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G.; Heijboer, A.C.; Giustina, A. Consensus and Controversial Aspects of Vitamin D and COVID-19. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.B.; Norton, E.C.; McCullough, J.S.; Meltzer, D.O.; Lavigne, J.; Fiedler, V.C.; Gibbons, R.D. Association between Vitamin D Supplementation and COVID-19 Infection and Mortality. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasis-Keever, M.A.; López-Alarcón, M.G.; Miranda-Novales, G.; Zurita-Cruz, J.N.; Barrada-Vázquez, A.S.; González-Ibarra, J.; Martínez-Reyes, M.; Grajales-Muñiz, C.; Santacruz-Tinoco, C.E.; Martínez-Miguel, B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Vitamin D Supplementation to Prevent COVID-19 in Frontline Healthcare Workers. A Randomized Clinical Trial. Arch. Med. Res. 2022, 53, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D.A.; Holt, H.; Greenig, M.; Talaei, M.; Perdek, N.; Pfeffer, P.; Vivaldi, G.; Maltby, S.; Symons, J.; Barlow, N.L.; et al. Effect of a Test-and-Treat Approach to Vitamin D Supplementation on Risk of All Cause Acute Respiratory Tract Infection and Covid-19: Phase 3 Randomised Controlled Trial (CORONAVIT). BMJ 2022, 378, e071230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiller, C.; Martineau, A. Modulation of the Immune Response to Respiratory Viruses by Vitamin D. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4240–4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keutmann, M.; Hermes, G.; Meinberger, D.; Roth, A.; Stemler, J.; Cornely, O.A.; Klatt, A.R.; Streichert, T. The Ratio of Serum LL-37 Levels to Blood Leucocyte Count Correlates with COVID-19 Severity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudryashova, E.; Zani, A.; Vilmen, G.; Sharma, A.; Lu, W.; Yount, J.S.; Kudryashov, D.S. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Human Defensin HNP1 and Retrocyclin RC-101. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 434, 167225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilezikian, J.P.; Bikle, D.; Hewison, M.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Formenti, A.M.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; Nair, N.; Babalyan, V.; Hutchings, N.; et al. MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: Vitamin D and COVID-19. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 183, R133–R147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalakis, K.; Ilias, I. SARS-CoV -2 Infection and Obesity: Common Inflammatory and Metabolic Aspects. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020, 14, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Li, P.; Dai, S.; Wang, G.; Li, W.; Song, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, S. Is Prior Bariatric Surgery Associated with Poor COVID-19 Outcomes? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.C.; Benotti, P.N.; Fano, R.M.; Dove, J.T.; Rolston, D.D.; Petrick, A.T.; Still, C.D. Prior Metabolic Surgery Reduced COVID-19 Severity: Systematic Analysis from Year One of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannelli, A.; Bouam, S.; Schneck, A.-S.; Frey, S.; Zarca, K.; Gugenheim, J.; Alifano, M. The Impact of Previous History of Bariatric Surgery on Outcome of COVID-19. A Nationwide Medico-Administrative French Study. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.-A.; de Jersey, S.; Seymour, M.; Hopkins, G.; Hickman, I.; Osland, E. Iron, Vitamin B12, Folate and Copper Deficiency after Bariatric Surgery and the Impact on Anaemia: A Systematic Review. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 4542–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, B.S.; Finelli, F.C.; Shope, T.R.; Koch, T.R. Nutritional Deficiencies after Bariatric Surgery. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusti, V.; Suter, M.; Héraïef, E.; Gaillard, R.C.; Burckhardt, P. Effects of Laparoscopic Gastric Banding on Body Composition, Metabolic Profile and Nutritional Status of Obese Women: 12-Months Follow-Up. Obes. Surg. 2004, 14, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Marroquin, E.; Xie, L.; Uppuluri, M.; Almandoz, J.P.; de la Cruz-Muñoz, N.; Messiah, S.E. Immunosuppression and Clostridioides (Clostridium) Difficile Infection Risk in Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2021, 233, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Milajerdi, A. Major Dietary Patterns in Relation to Disease Severity, Symptoms, and Inflammatory Markers in Patients Recovered from COVID-19. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Rebholz, C.M.; Hegde, S.; LaFiura, C.; Raghavan, M.; Lloyd, J.F.; Cheng, S.; Seidelmann, S.B. Plant-Based Diets, Pescatarian Diets and COVID-19 Severity: A Population-Based Case–Control Study in Six Countries. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2021, 4, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-Robles, E.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Badillo, H.; Calderón-Juárez, M.; García-Bárcenas, C.A.; Ledesma-Pérez, P.D.; Lerma, A.; Lerma, C. Association between Severity of COVID-19 Symptoms and Habitual Food Intake in Adult Outpatients. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2021, 4, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Nutrition, Immunity and COVID-19. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2020, 3, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanger, M.J.; Hill, M.A.; Angelidi, A.M.; Dalamaga, M.; Sowers, J.R.; Mantzoros, C.S. Covid-19 and Disparities in Nutrition and Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Chu, H.; Yang, D.; Sze, K.-H.; Lai, P.-M.; Yuan, S.; Shuai, H.; Wang, Y.; Kao, R.Y.-T.; Chan, J.F.-W.; et al. Characterization of the Lipidomic Profile of Human Coronavirus-Infected Cells: Implications for Lipid Metabolism Remodeling upon Coronavirus Replication. Viruses 2019, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiser, A.R. Could Dietary Factors Reduce COVID-19 Mortality Rates? Moderating the Inflammatory State. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2021, 27, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Jaam, M.; Nazar, Z.; Stewart, D.; Shaito, A. Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Herbs and Supplementary Medications with COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | No | Yes | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=10,000 | N=8,955 | N=1,045 | ||

| Age (years) | 40.3 ± (13.1 | 40.4 ± 13.1 | 39.6 ± (12.7 | 0.083 |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 4,780 (47.8%) | 4,351 (48.6%) | 429 (41.1%) | |

| Female | 5,220 (52.2%) | 4,604 (51.4%) | 616 (58.9%) | |

| Educational level | 0.020 | |||

| Low | 1,796 (18.0%) | 1,594 (17.8%) | 202 (19.3%) | |

| Medium | 3,040 (30.4%) | 2,694 (30.1%) | 346 (33.1%) | |

| High | 5,164 (51.6%) | 4,667 (52.1%) | 497 (47.6%) | |

| Smoking status | <0.001 | |||

| None | 6,468 (64.7%) | 5,695 (63.6%) | 773 (74.0%) | |

| Smoker | 1,866 (18.7%) | 1,735 (19.4%) | 131 (12.5%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 1,666 (16.7%) | 1,525 (17.0%) | 141 (13.5%) | |

| Leisure time physical activity (MET hours/week) |

24.9 ± 52.5 | 24.9 ± 51.0 | 24.3 ± (64.2 | 0.74 |

| Modern dietary pattern score | 0.0 ± (1.00 | -0.01 ± 1.0 | 0.1 ± 1.1 | 0.001 |

| Prudent dietary pattern score | 0.0 ± 1.00 | -0.0 ± 1.0 | 0.02 ± 0.9 | 0.45 |

| Cereal dietary pattern score | 0.0 ± 1.00 | -0.01 ± 1.0 | 0.1 ± 1.1 | 0.032 |

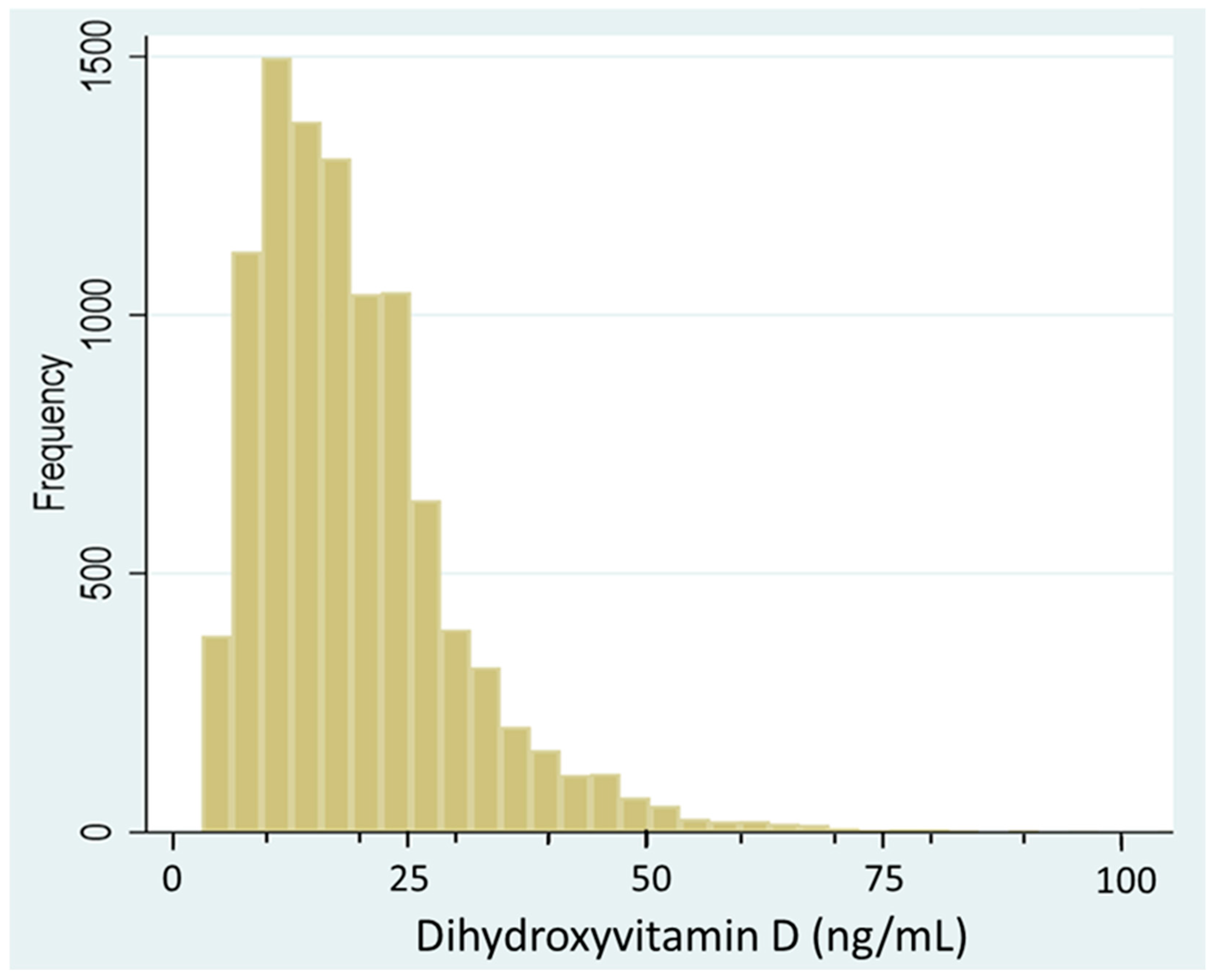

| Serum vitamin D (ng/mL) | 19.3 ± 11.1 | 19.3 ± 1.1) | 18.9 ± 10.9) | 0.22 |

| Hypertension | 1,638 (16.4%) | 1,479 (16.5%) | 159 (15.2%) | 0.28 |

| Diabetes | 2,026 (20.3%) | 1,808 (20.3%) | 218 (21.0%) | 0.60 |

| History of bariatric surgery | 1,213 (12.1%) | 1,058 (11.8%) | 155 (14.9%) | 0.004 |

| BMI categories | 0.051 | |||

| Normal | 2,112 (21.1%) | 1,905 (21.3%) | 207 (19.8%) | |

| Overweight | 3,462 (34.7%) | 3,123 (34.9%) | 339 (32.4%) | |

| Obese | 4,417 (44.2%) | 3,918 (43.8%) | 499 (47.8%) | |

| Dietary supplement use | ||||

| Multivitamin/minerals | 3,565 (35.6%) | 3,174 (35.4%) | 391 (37.4%) | 0.21 |

| Calcium | 726 (7.3%) | 649 (7.2%) | 77 (7.4%) | 0.89 |

| Folic acid | 316 (3.2%) | 276 (3.1%) | 40 (3.8%) | 0.19 |

| Iron | 1,366 (13.7%) | 1,208 (13.5%) | 158 (15.1%) | 0.15 |

| Vitamin B | 806 (8.1%) | 728 (8.1%) | 78 (7.5%) | 0.45 |

| Vitamin C | 665 (6.7%) | 604 (6.7%) | 61 (5.8%) | 0.27 |

| Vitamin D | 2,402 (24.0%) | 2,166 (24.2%) | 236 (22.6%) | 0.25 |

| Other supplements | 3,315 (33.1%) | 2,968 (33.1%) | 347 (33.2%) | 0.97 |

| Any supplement use | 5,977 (59.8%) | 5,339 (59.6%) | 638 (61.1%) | 0.37 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | OR [95% CI] | p-value | |

| Vitamin D | 0.81 (0.68-0.96) | 0.018 | 0.82 (0.69-0.97) | 0.022 |

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.050 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.084 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) | 0.715 | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) | 0.704 |

| Education | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Medium | 0.95 (0.77-1.17) | 0.641 | 0.94 (0.76-1.17) | 0.588 |

| High | 0.86 (0.71-1.04) | 0.124 | 0.85 (0.70-1.03) | 0.096 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Non | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Smoker | 0.55 (0.44-0.68) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.44-0.68) | <0.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 0.70 (0.57-0.86) | <0.001 | 0.70 (0.57-0.86) | <0.001 |

| Leisure time PA (MET hours/week) | ||||

| T1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| T2 | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | 0.817 | 1.03 (0.88-1.21) | 0.737 |

| T3 | 0.94 (0.79-1.11) | 0.472 | 0.93 (0.79-1.10) | 0.404 |

| BMI level | ||||

| Normal | 1.00 | |||

| Overweight | 1.09 (0.90-1.32) | 0.379 | ||

| Obese | 1.20 (1.00-1.45) | 0.049 | ||

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.09 (0.91-1.31) | 0.338 | 1.10 (0.92-1.32) | 0.308 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.76-1.16) | 0.547 | 0.96 (0.78-1.18) | 0.693 |

| Modern dietary pattern | 1.09 (1.02-1.16) | 0.012 | 1.08 (1.01-1.16) | 0.018 |

| Prudent dietary pattern | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | 0.344 | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | 0.307 |

| Cereal dietary pattern | 1.05 (0.99-1.12) | 0.100 | 1.05 (0.99-1.12) | 0.092 |

| Any supplement use | 1.12 (0.96-1.30) | 0.155 | 1.10 (0.95-1.28) | 0.205 |

| History of bariatric surgery | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.24 (1.03-1.50) | 0.022 | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Any supplement use | 1.00 (0.87-1.14) | 0.979 | 1.03 (0.90-1.19) | 0.652 | 1.02 (0.89-1.18) | 0.749 |

| Multivitamin/minerals | 1.07 (0.94-1.22) | 0.322 | 1.17 (0.99-1.40) | 0.067 | 1.16 (0.97-1.38) | 0.096 |

| Calcium | 0.96 (0.75-1.22) | 0.723 | 0.97 (0.75-1.25) | 0.792 | 0.96 (0.75-1.24) | 0.775 |

| Folic acid | 1.13 (0.80-1.59) | 0.485 | 1.18 (0.83-1.66) | 0.356 | 1.17 (0.82-1.65) | 0.385 |

| Iron | 1.01 (0.84-1.22) | 0.886 | 1.02 (0.84-1.24) | 0.869 | 1.00 (0.82-1.22) | 1.000 |

| Other supplements | 0.94 (0.81-1.08) | 0.357 | 0.90 (0.76-1.06) | 0.197 | 0.90 (0.76-1.06) | 0.216 |

| Vitamin B | 0.87 (0.68-1.12) | 0.281 | 0.89 (0.69-1.14) | 0.348 | 0.87 (0.68-1.12) | 0.288 |

| Vitamin C | 0.84 (0.64-1.10) | 0.210 | 0.86 (0.65-1.14) | 0.288 | 0.86 (0.65-1.13) | 0.276 |

| Vitamin D | 0.85 (0.73-1.00) | 0.046 | 0.81 (0.68-0.96) | 0.018 | 0.82 (0.69-0.97) | 0.022 |

| Quartiles of serum VD | |||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | p-value | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 | 1.19 (0.99-1.42) | 1.04 (0.85-1.26) | 0.94 (0.77-1.15) | 0.324 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.19 (1.00-1.43) | 1.06 (0.87-1.29) | 0.98 (0.80-1.20) | 0.552 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).