1. Introduction

The supply chain management (SCM) mainly focuses on

amongst others, the optimisation of customer satisfaction and therefore, to

neglect the important matters of SCM could be damaging to any type of business

for which SCM is possibly a competitive differentiator [62,71]. Most notably, some of these businesses

would be operational in manufacturing, retail, and distribution industries.

However, the value of SCM is reflected in how large firms have used their

supply chains as strategic weapons to gain an advantage over peers because

their SCM competencies influence revenue growth through extensive operational

and sustainable innovation [23]. To implement and capitalise on the latest supply

chain innovations, companies need talent with the right skills, experience and

in-depth business and supply chain knowledge to apply the latest tools and

methods [49]. However, most sustainable innovations in SCM

build on existing achievements and reconfiguration of familiar methods and

technologies rather than inventing new ones [50].

Proponents of SCM therefore acknowledge that a change in process and

organisational strategy is required to compete in today’s market, particularly

in managing and analysing products and raw materials flows [54].

The interest of many firms is to accelerate

performance to gain a competitiveness and become proactive in managing their

supply chains in a global setting [29]. The

importance of SCM is therefore applicable to both developed and developing

countries. On the other hand, the shift in politics, unstable economies, lack

of basic infrastructure and limited application of enterprise management

technologies are also, the norm in developing countries [33]. In this

regard, leading companies, therefore, no longer focus narrowly on driving

efficiency and cost cutting, but the focus at these companies has changed from

supply chains being an enabler of company successes. Brown

and Murray [13] suggest that regardless of

which performance improvement approach a company uses, a continuous improvement

of such approach in performance remains critical for the success of a company.

Firms with competencies of inimitable resources,

value creating strategies and grip on market influence have more opportunities

to attain superior performance [4] because the

business environment is very competitive. Brem and

Viardot [12] posit that sustainable

innovation is amongst the key driver for performance and growth in business and

provides a stronger chance for competitiveness that helps to fast-track the

rate of change as well as adaptation to the global business environment. In

addition, sustainable innovation plays a central role in the thinking about

transformational leadership for organisations [18]. From its

multiple activities, one key purpose of sustainable innovation from an economic

perspective is to differentiate firms’ products and improve their competitive

position in the market, which will earn the innovator an extraordinary income

based on this privileged position [43].

The competitive milieu for businesses is

inevitable, whether in a developing or a developed economy. The difference,

however, is that, in developing economies, the inadequate channels of

distribution do not reach most consumers, unlike in developed economies, where

there are large retailers in the supply chains [57]. To

survive competition in developing economies, supply chain enterprises must be

able to deal with external and internal uncertainties by adopting supply chain

flexibility as an approach for coping with sources of uncertainty [31]. In essence, thoughtful supply chain planning

should therefore be such that it considers both known and forecasted unknown

elements of the future as not just critical for success, but also as a

requirement for survival [67]. In addition, the duty of supply chain managers

should entail keeping in touch with other important aspects such as cultural,

historical, and political trends, as this can change the playing field at

virtually any time to the detriment of the company and its stakeholders [58].

It is conceivable to note that leading companies

treat their supply chains as dynamic hedges against improbability by vigorously

and frequently examining as well as reconfiguring their broader supply networks

towards economic circumstances years ahead [40].

Those companies therefore tend to achieve a much higher degree of visibility,

coordination, and dependable processes both within and across the plan, source,

manufacture, deliver and return functions, but also in partnership with sales

and marketing and product management organisations in lines of business [5]. Grosspietch and

Brinkhoff [27] argue that leadership in

supply chain transformation is one of the most difficult, yet most crucial

factors for delivering and sustaining impact, and therefore success in the SCL

discipline leans heavily on some of the very leadership skills that distinguish

the world’s best chief executive officers [59].

What differentiates the leaders is that they have moved beyond the ‘words and

presentation slides’ to make the hard adjustments that are needed through the

establishment [28]. Stratman

[59] further perceives the supply chain

leader’s vantage point as that which incorporates the entire value chain and

for which the effective supply chain leaders consistently interact with key

players in the business.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Leadership

Leadership is a complex concept that has been

around for thousands of years and yet there is still no single definition to

agree upon by all and sundry [19]

and it is defined from a multidimensional perspective [17]. However, Leadership has conventionally

been explored with an emphasis on the features and behaviours of people, and

their effects on teammates and associations [25].

Typically, it is characterized and defined by leaders' traits, abilities,

characters and behaviours and it focuses on group activities which are based on

social influence and revolve around common goals, objectives, visions, or

missions [45]. Some early researchers in

operations and supply chain management have paid attention to the concept of

leadership at an organizational level, although they tend to discuss power and

leadership interchangeably [32]. However,

leadership behaviours can broadly be divided into transformational,

transactional, and laissez-fare leadership behaviour [24].

Notably, laissez-fare leadership is believed to be the passive avoidant as well

as ineffective type in which leaders evade their supervisory obligations to

their juniors [9,19, 53].

2.1.1. Transformational Leadership

Typically, transformational leaders are described

as inspirational to their followers to adopt goals and values that are

consistent with the vision of the leader [55, 68].

Transformational leadership includes four behaviours, namely idealised influence

or charisma, individualised consideration, inspirational motivation, and

intellectual stimulation [8,10,11,15,18,37,48,62,66,72].

Transformational leaders can inspire and motivate their followers [22] by influencing the process to exchange valued

rewards for performance [69]. Compared to

transactional leadership, it has advantages of leadership and organisational

effectiveness [53]. However, transformational

leadership is criticised for making it difficult to define its parameters

because it is broad-based in its nature and therefore covers more facets such

as creating a vision, motivating, being a change agent, building trust and many

other qualities [10].

2.1.2. Transactional Leadership

This leadership depends on individual initiative to

contact others for the purpose of an exchange of things as well as the

assumption that subordinates and systems work better under a clear chain of

command [62]. Arguably, transactional

leadership is a short-term managerial orientation that has limited capability

to generate long-term, sustainable, and competitive organisations [41]. The focus is on the physical and security

needs of subordinates [37] and on the

motivation of followers by providing either rewards for good performance or

discipline for shoddy performance [24]. The

main strength of transactional leadership is that followers are challenged

through rewards, while the weakness is that it uses negative reinforcement [10]. With this approach, there can be exchanges in

value without any mutual pursuit of higher-order purpose, and the result can be

of a workplace that is efficient and productive yet limited as compared to

under transformational leadership [20,47].

2.1.3. Laissez-Fare Leadership

Laissez-fare leadership was introduced as a passive

avoidant and is considered an ineffective type of leadership style in which

leaders shirk their supervisory duties to their subordinates [9,19,53). In essence, it is more of a representation for

lack of leadership and avoidance of clarification of expectations, addressing

of conflicts and making of decisions [46,63,69]. In other words, as leaders continue to

offer little support to their subordinates and pay no attention to production

or the completion of duties [7], they either

choose not to intervene in the work affairs of subordinates or may completely

avoid their responsibilities as superiors and are therefore unlikely to build

any relationship with their subordinates [37].

The factor that distinguishes laissez-fare leaders from other leaders is that

they abrogate their leadership responsibilities by being absent [48]. In other word, leaders are not involved in the

work of subordinates and the unit, in the sense that it minimises their

involvement in decision making within the organisation [18]. However, despite the careless behaviour of

laissez-fare leadership, it is suitable in a situation where employees are

capable and motivated to make their own decisions that are in line with the

goals of the organisation and where there is no requirement for central

coordination [1].

2.2. Supply Chain Leadership

SCL contributes to the improvement of operational

performance, buyer-supplier relationships, and sustainability [45]. As cognitive contemporary businesses became

more sophisticated than they have been in the past, Sukati, Hamid, Baharum and Mdyusoff [61]

assert that the process of development in business have been characterized

by more interconnected and interdependent, short product lifecycles as well as

the introduction of varied products. SCL is therefore identified as potentially

significant but is yet to emerge as a distinct field of scholarly research [25]. It involves awareness of risk and unforeseen

business challenges and how to decisively deal with them. Naturally, leading

companies treat their supply chains as dynamic hedges against uncertainty by

actively and regularly examining or even reconfiguring their broader supply

networks towards economic conditions years ahead [40].

Those companies tend to achieve a much higher degree of visibility,

coordination, and reliable processes both within and across the plan, source,

manufacture, delivery and return functions, but also in partnership with sales

and marketing and product management organizations in lines of business [5]. Grosspietch and

Brinkhoff [27] argue that leadership in

supply chain is the most difficult, yet most crucial factors for delivering and

sustaining impact. Success in the SCL discipline therefore leans heavily on

some of the very leadership skills that distinguish the world’s best management

[59]. What differentiates the leaders is that

they sought to move to make the hard changes that are needed through the

organization [28]. Thus, supply chain leader’s

vantage resemble that which encompasses the entire value chain and for which

the best supply chain leaders regularly interact with key players in the

business.

2.3. Supply Chain Management

SCM is still considered as one of the most

challenging fields which emphasizes interactions among different sectors,

primarily marketing, logistics, and production [21].

It has been applied in various industries to increase productivity [70] and an important source of competitive

advantage [44]. However, the SCM phenomenon is

once again at a crossroad in the age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR)

with the rapid development of information-led technologies [44]. There is, therefore, a need for SCM to develop

an adequate solution in mitigation of such developments [21]. Successful companies are seen as those who

consistently improve their performance and successfully manage supply chain

activities, and hence regarded as supply chain leaders. Mehrjerdi

[42] asserts that leadership must fully

understand SCM and the value that it can bring to the firm’s bottom line.

Overall, firms identified as supply chain leaders consistently outperformed

their non-supply chain leader peers in areas such as accounting-based cost and

activity and liquidity ratios [26]. Globally,

these companies sought to explore the concept of SCM and leadership to improve

revenue growth. Grosspietch and Brinkhoff [27]

suggest that successful companies are cognitive that excellent SCM is a

competitive advantage and therefore started to adapt their businesses

accordingly. As a result, SCM had been recognized by corporate business as a

necessary business function and may be used for a competitive advantage [65]. In addition, supply chains need to adopt

strategies that improve the ability to respond to unpredictable changes in

markets while increasing the levels of environmental turbulence, in terms of

both volume and variety [16]. Every company

therefore develops supply chain strategies and priorities that are uniquely

suited to corporate and market context [28].

Ultimately, SCM has increasingly become a source for competitiveness as smarter

supply chains are inclined to use their intelligence and advanced analytics to

identify good customer segments and tailor their offerings accordingly [14].

2.4. Sustainability in Innovation

The uncertainty and instability of the business

environment combined with heightened competitive pressure have pushed

organizations to find new ways of running their businesses [2]. Similarly, in an era of vast competition, the

biggest challenge of a company is to determine how to break the status quo and

achieve dominance [36]. Business success is

therefore increasingly dependent upon innovation and sustainability. Innovation

is related with knowledge creation and sharing activities within and between

organizations [38]. For it is the innovation

capability of firms that enables them to respond to change in the environment,

develop solutions to emerging problems, and take necessary actions [52]. sustainable innovation must occur to achieve

this important global agenda [3]. The three

phases of innovation include exploration, exploitation, and diffusion.

2.4.1. Exploration

In essence, exploration has more to do with

development of new alternatives and therefore focuses on the ideal of pursuing

more knowledge to the firm in the present moment than they did in the past [60]. Activities associated with exploratory

innovations are often riskier, as they require more financial investments [56] and because exploratory innovations are radical

novelties that aim to serve present and future customers [56].

2.4.2. Exploitation

Firms that focus on exploitation pursue less new

knowledge for the present moment than they would have done in the past [60]. Exploitative innovations are incremental in

character with a focus on the needs of existing customers [56]. In general, activities that are associated

with exploitative innovations offer less risk and require little investments,

which lead to new, adapted products [56]. To

keep up with competition technologically, firms will need to balance their

exploitative innovation portfolio with some exploratory activities because

failure to explore new technology may result in outdated innovations that

ultimately do not meet customer demand [56].

2.4.3. Diffusion

Diffusion is the term normally used to describe the

rate at which innovations are adopted by consumers or users and come into

general use [51]. Diffusion occurs when the

system of users makes it possible for them to acquire knowledge about new

technology and to share information and opinions among themselves as potential

users through the available communication channels [39].

This process, as MacVaugh and Schiavone [39]

assert, occurs progressively within one market. It further occurs in systems

that are complex in nature where networks connecting system members are

overlapping, multiple and complex [51].

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Population

All the 400 JSE-listed companies in 2015 was the

target population (N = 400) and a purposive sample of the top 100 JSE-listed

companies was considered for this study (n = 100) and the response rate was

46%. The choice of the best 100 JSE-listed companies was influenced by their

highest shareholder returns over the past five years. The top 100 JSE-listed

companies are stratified into the following industries, as depicted in

Table 1.

Stratified sampling was aimed at categorising the

companies into relatively homogeneous sub-groups in accordance with the

standard industrial classification relevant to the research and to attain

greater precision as well as representativeness of the sample. Furthermore, the

classification totals accounted for manufacturing 9 (100*.09); retail,

wholesale trade, commercial agents, and allied services 18 (100*.18); mining,

quarrying and agriculture 8 (100*.08); ICT, transport, logistics and storage 18

(100*.18); finance and business services 25 (100*.25); and catering,

accommodation, property, and hospitality 22 (100*.22).

3.2. Data Collection

The study collected statistical data using online Survey- monkey questionnaire from 46 of top 100 JSE-listed companies with the intention to discover SCL strategic actions that drive innovation and competitiveness in the company. The survey was stored on a server that was controlled by the researcher, while the participants were asked to visit the website by simply clicking an e-mail link to participate. A series of questions were posed using a five-point Likert- scale. The Likert-type responses were used to ask participants to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements.

3.3. Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to analyze raw data to describe and summarize it to recognize some of the emerging patterns to create tables and graphical summaries to facilitate statistical comments for the discussion of the results. Factor analysis was used to determine the latent variables that underlie a set of items and then summarize data parsimoniously in a manner that allows relationships and patterns to be easily interpreted and understood. Inferential Analysis was used for drawing inferences about the JSE listed companies from the sample of the top 100 companies.

3.4. Quality Assurance of the Study

The face validity of the questionnaire was enhanced by conducting a pilot study before finalising the questionnaire whereas content validity was assured by asking colleagues within the field of SCM to review the constructs to evaluate the validity of the indicators. A further attention was paid to constructs such as characteristics, creativity, innovation, and motivation of SCL, while measuring them against previous studies and publications to ensure construct validity. In addition, to ensure criterion validity, the survey instrument was reviewed by experts in SCM, entrepreneurship, operations, and manufacturing strategy and pre-tested on some managers to gain clarity. Furthermore, a solid documentation of the research process was put in place while using standardisation in the survey to ensure reliability in this study.

3.5. Ethical Consideration

Prospective research participants were informed about the procedures and risks involved in the research and were allowed to give their consent to participate. Participation in this study was therefore based on a voluntary basis, while both physical and psychological harm were avoided at all costs. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Unisa Ethics Committee in line with the university’s Policy on Research and Ethics. In addition, an assurance was given to the participants of confidential treatment of their responses as well as their participation in the study. Thus, no person or company had access to the completed questionnaires.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive and Factor Analysis

4.1.1. Supply Chain Leadership

SCL refers to the keenness of the company to accelerate operational performance through sustainable innovation to gain competitiveness through a proactive management of supply chain activities and through the awareness of risks and unforeseen challenges for a secured market for goods and services.

Figure 1 below illustrates how the measures rank based on the importance of the different factors to their SCL position. Increased profitability ranks the highest on average and Increased capacity for decision making the lowest. It should, however, be noted that on average all factors are important as illustrated by the average scale scores of above four for each factor.

4.1.2. Competitiveness

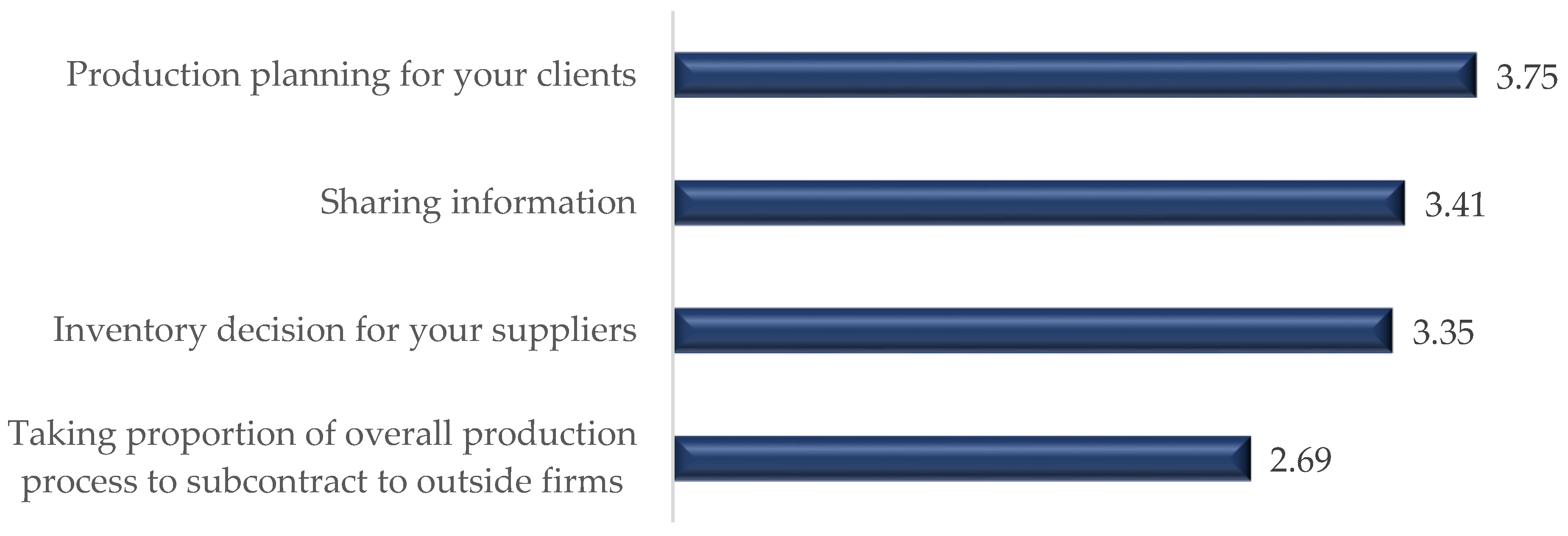

Various approaches are used by companies to obtain competitive advantage. The actions that were agreed upon to obtain a competitive advantage include production planning for clients, inventory decisions for suppliers and sharing of information. There was, however, a disagreement on the suggestion that competitive advantage is sought by subcontracting a portion of the overall production to outside firms. The disagreement on subcontracting is indicated by a score of below three as illustrated by

Figure 2 suggests that companies prefer to increase capacity for production processes within the companies.

4.1.3. Sustainable Innovation

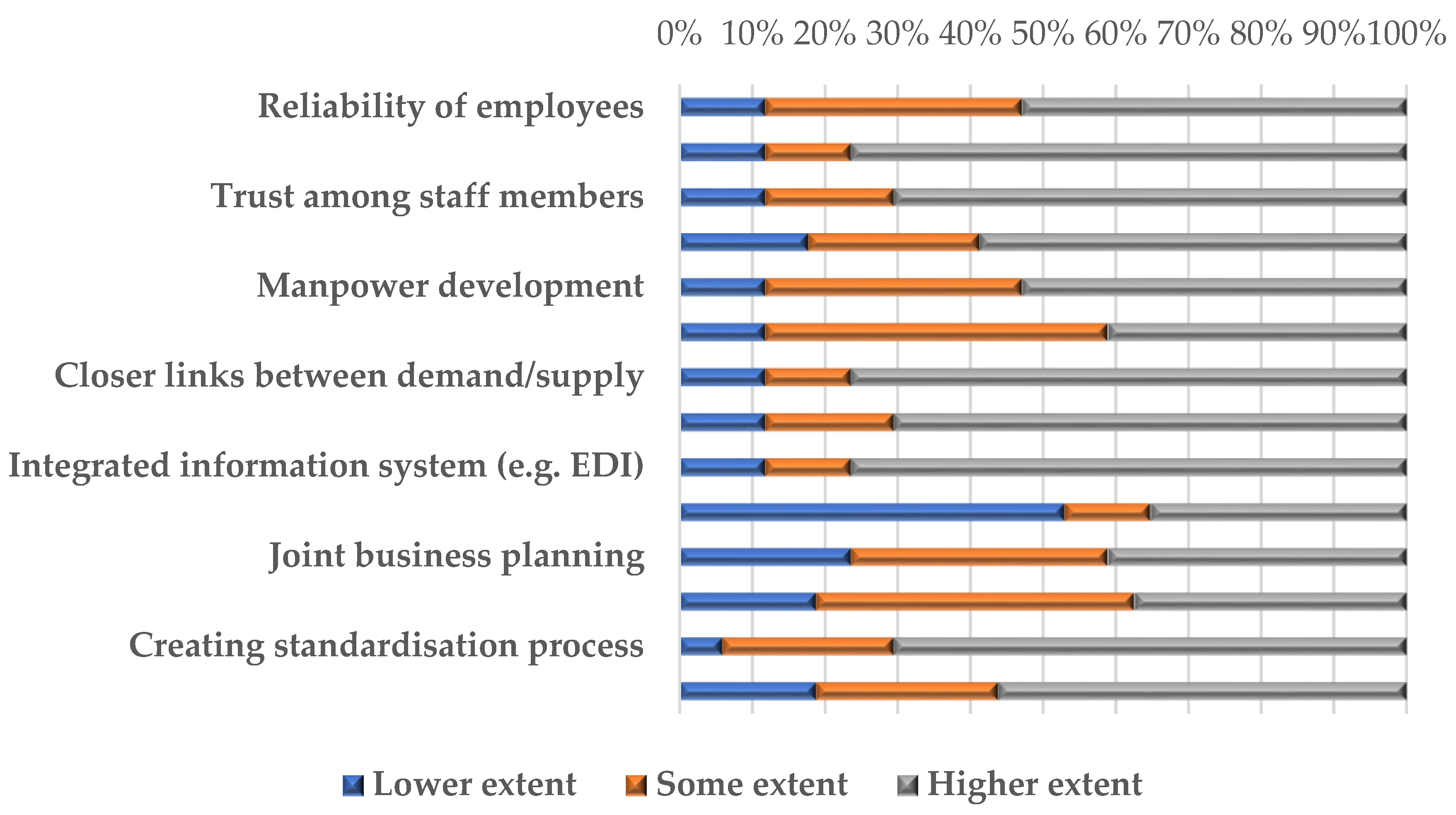

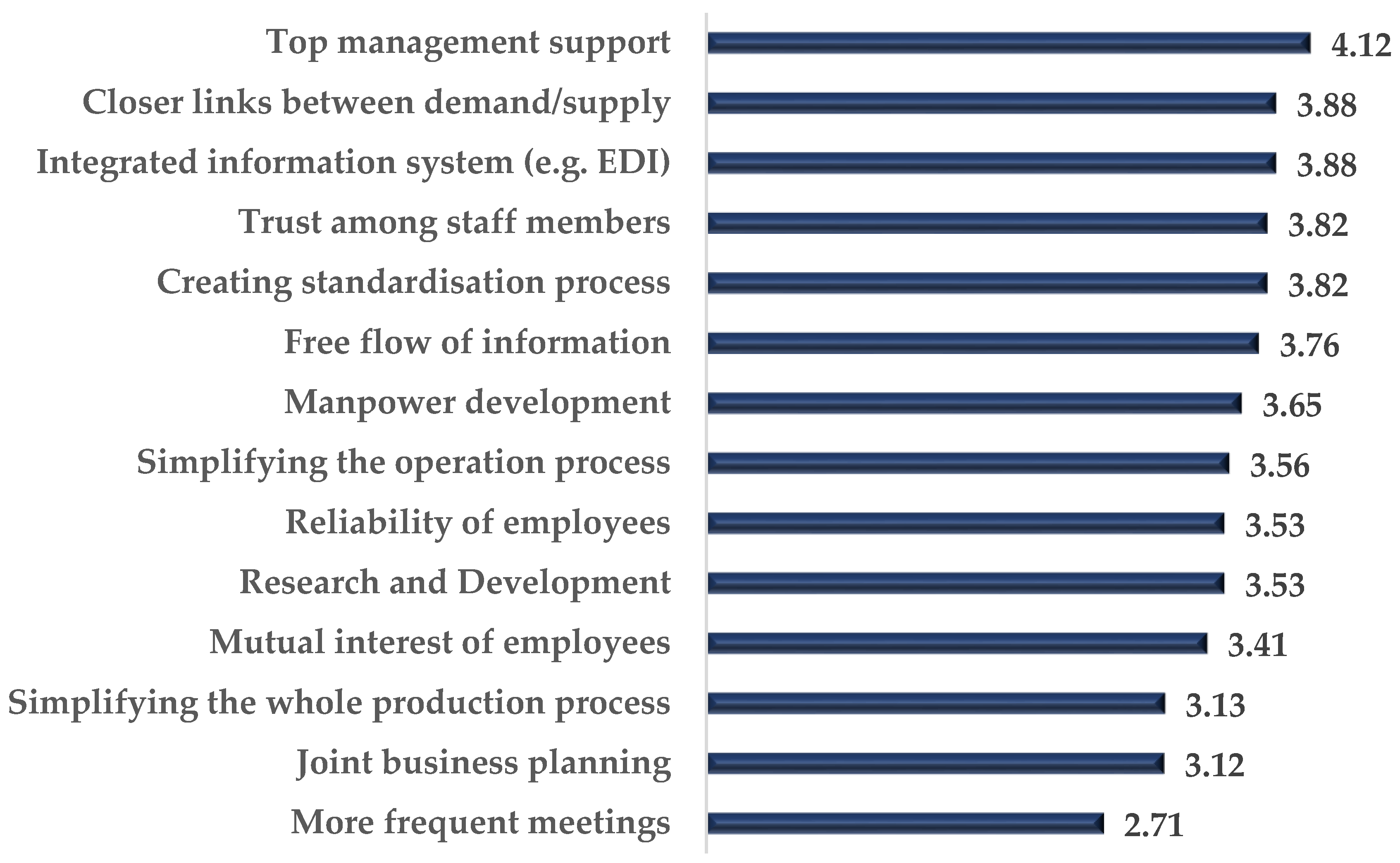

Innovation refers to the ability of the company to provide creative and meaningful solutions either in the form of products or services to both individuals and operational problems and the needs for survival in a competitive business environment. Factors that affect the development of new innovative ideas towards SCM at a higher extent are top management support, closer links between demand/supply, integrated information systems (e.g. EDI), trust among staff members, free flow of information and creating a standardisation process, while at a lower extent, the factors are more frequent meetings, joint business planning, simplifying the whole production process, simplifying the operation process and mutual interest of employees. As can be seen from

Figure 3 below, closer links between demand/supply and Integrated information system affect the development of new innovative ideas toward SCM to the highest extent while research and development and simplifying the whole production process do so to the least extent.

4.2. Inferential Analysis

Both dependent and independent variables in this study informed the use of t-tests as well as ANOVAs for non-parametric analyses in the form of Mann-Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests as ANOVA tests. Therefore, through inferential statistical analysis, the inferences about the JSE-listed companies were made by estimating the parameters as well as testing the hypotheses.

Research Hypothesis 1: Subjective opinions of supply chain managers and supply chain experts will highlight sustainable innovation as necessary activities towards companies’ level of competitiveness.

Through the cluster group comparisons, the discussion under this hypothesis is centred on the valuable subjective opinions of managers and experts in the field of SCM on the basis that sustainable innovation is necessary to achieve competitiveness in the market. To determine whether the company’s position for effective SCM influences the extent to which the different functions are perceived to affect the efficiency of SCM and how well it is positioned to affect the efficiency of SCM, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare participants who are well positioned to those who still need to be well positioned.

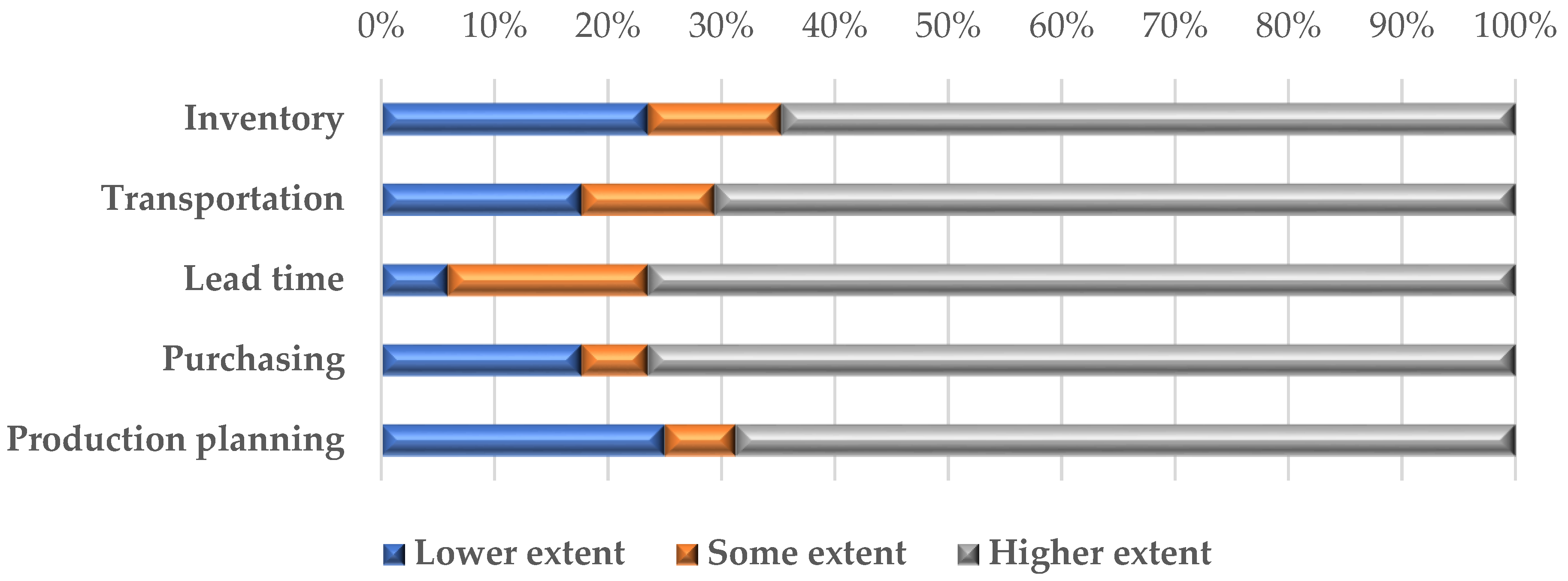

Figure 4 illustrates the extent to which the participant considers the functions of inter alia inventory, transportation, lead time, purchasing and production planning to affect the efficiency of SCM and how well these functions are positioned for effective SCM and the effect thereof. How well the company is positioned for effective SCM does not have a significant effect on the extent to which the different functions are perceived to affect the efficiency of SCM in their companies.

The results provide a reflection that sustainable innovation is necessary for the company and contribute towards a competitiveness. However, the results show that the position of the company for effective SCM has very little impact on the actual functions that are perceived to affect the efficiency of SCM in the company. Therefore, the functions of inventory, transportation, lead time, purchasing and production planning are independent functions that are not dictated by how well the company is positioned for effective SCM.

Research Hypothesis 2: Training and development will allow for proper implementation of sustainable innovation within a company for the attainment of SCL.

Through the cluster group comparisons, the discussion under this hypothesis is centred on the understanding that trained employees can implement sustainable innovation with ease. To determine whether the company’s position for effective SCM influences the extent to which different factors affect the development of new innovative ideas regarding SCM in the company and how well the company is positioned for effective SCM for the development of innovative ideas towards SCM, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the participants who are well positioned to those who still need to be positioned. Various factors that play a role in the development of new innovative ideas towards SCM include reliability of employees, top management support, trust among staff members, mutual interest of employees, manpower development, R&D, closer links between demand and supply, free flow of information, more frequent meetings, joint business planning, simplifying the whole production process, creating a standardisation process, and simplifying the operation process. All these factors are vital for training of employees for the proper implementation of sustainable innovation within the company. How well the company is positioned for effective SCM does not have a significant effect on the extent to which the participants perceived the different factors to affect the development of new innovative ideas regarding SCM in their companies.

Figure 5.

Factors for the development of innovation ideas.

Figure 5.

Factors for the development of innovation ideas.

Research Hypothesis 3: The best supply chain companies in a developing economy will share the common SCM characteristics about sustainable innovation.

Through the cluster group comparisons, the discussion under this hypothesis is centred on detrimental effects of lack of sustainable innovation as well as the positive results that come with sustainable innovation. If sustainable innovation is lacking, SCM activities are set to be weakened, and when sustainable innovation is in place, a higher level of visibility, reliability and better coordination of functions could be anticipated. To determine whether the two groups differed regarding whether their companies have a separate SCM department, whether they have an SCM strategic plan and whether they operate under any public policy on SCM, cross-tabulations were used. The data did not have enough statistical power (the sample was too small) to satisfy the basic assumption of the Chi-square test of independence that specifies that no more than 20% of the cells may have an expected cell count of less than 5. To get some sense of whether the proportions differed significantly, the column proportions were compared using Bonferroni adjustment for p-values. When the subscripts in two different columns differ, for example A in one column and B in the other column, it means that the difference between the column proportions (76.5 – 36.4 = 40.1) is significantly different from zero.

Table 2 illustrates whether the companies have a separate SCM department or not. How well the company is positioned for effective SCM has a significant effect on whether the company has a separate SCM department or not. Specifically, those participants whose companies are not quite positioned for effective SCM tend more to have a separate SCM department than those that are well positioned. On the reverse side, those participants whose companies are quite positioned for effective SCM tend more not to have a separate SCM department than those that are well positioned. The results show an appreciation of the positioning of the company for effective SCM and clearly provide evidence that if the company is still to be positioned, certain actions must be taken, such as creating a separate SCM department that should collate activities for effective SCM, which will include ensuring that sustainable innovation is prioritised. However, a company that is well positioned for effective SCM (has innovation at the top of the agenda) has less worries and consider it peripheral to create a separate SCM department. The worries are lessened because already a higher degree of visibility, reliability and better coordination of functions is put in place, therefore it is well positioned for effective SCM. In other words, the creation of a separate SCM department is mostly dictated by how well the company is positioned for effective SCM, either well positioned or still trying to get there. The bottom line is that the positioning of the company for effective SCM remains a top priority for SCL.

4.3. Statistical Hypotheses

Ho1: There is no significant relationship between the achievement of a competitiveness in a developing economy and the company’s application of sustainable innovation.

Ha1: There is a significant relationship between the achievement of a competitiveness in a developing economy and the company’s application of sustainable innovation.

To determine whether the company’s position for effective SCM influences how important different factors are to the company for establishing its position in terms of SCL as well as how well the company is positioned for effective SCM, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the participants who are well positioned to those who still need to get there.

Table 3 illustrates that nine of the most important supply chain strategies available to companies for SCL position are improved customer satisfaction, increased profitability, reduction of bureaucracy/paperwork, increased market competitiveness, cost reduction, improved quality assurance, increased revenue growth, increased capacity for decision making and improved product management. On each strategy, the determination is made on how well the company is positioned for effective SCM to ultimately culminate in SCL for the company.

The results reflect that there is a significant difference between the groups at the 5% level of significance regarding how important they considered cost reduction to be within the organisation for its SCL position (U = 15.00, p < 0.05). Specifically, those participants with lower values on the three SCM readiness indices (MR = 7.36) considered the cost reduction as significantly less important for its SCL position than those with higher values on the three indices (MR = 12.00). Furthermore, there is a significant difference between the groups at the 5% level of significance regarding how important they considered the reduction of bureaucracy/paperwork for its SCL position (U = 18.00, p < 0.05). Specifically, those participants with lower values on the three SCM readiness indices (MR = 8.00) considered the reduction of bureaucracy/paperwork as significantly less important for its SCL position than those with higher values on the three indices (MR = 12.50).

5. Significant Contribution of the Study

The contribution in this study is that it is contextualised in a developing economy and the findings are meant to resonate with companies operating in such an economy. Even though there are studies examining SCL about innovation in developed economies and there are indeed a few in developing economies, the data-collection instruments for these concepts have been created, validated, and tested for reliability within the context of developing economies. Therefore, to achieve sustainability and innovative capabilities for competitive growth of the company, training and development of employees should be prioritised within a company for the attainment of SCL. Due to globalisation, training, and development in the implementation of sustainable innovation is crucial for narrowing the gap between developing economies and developed economies.

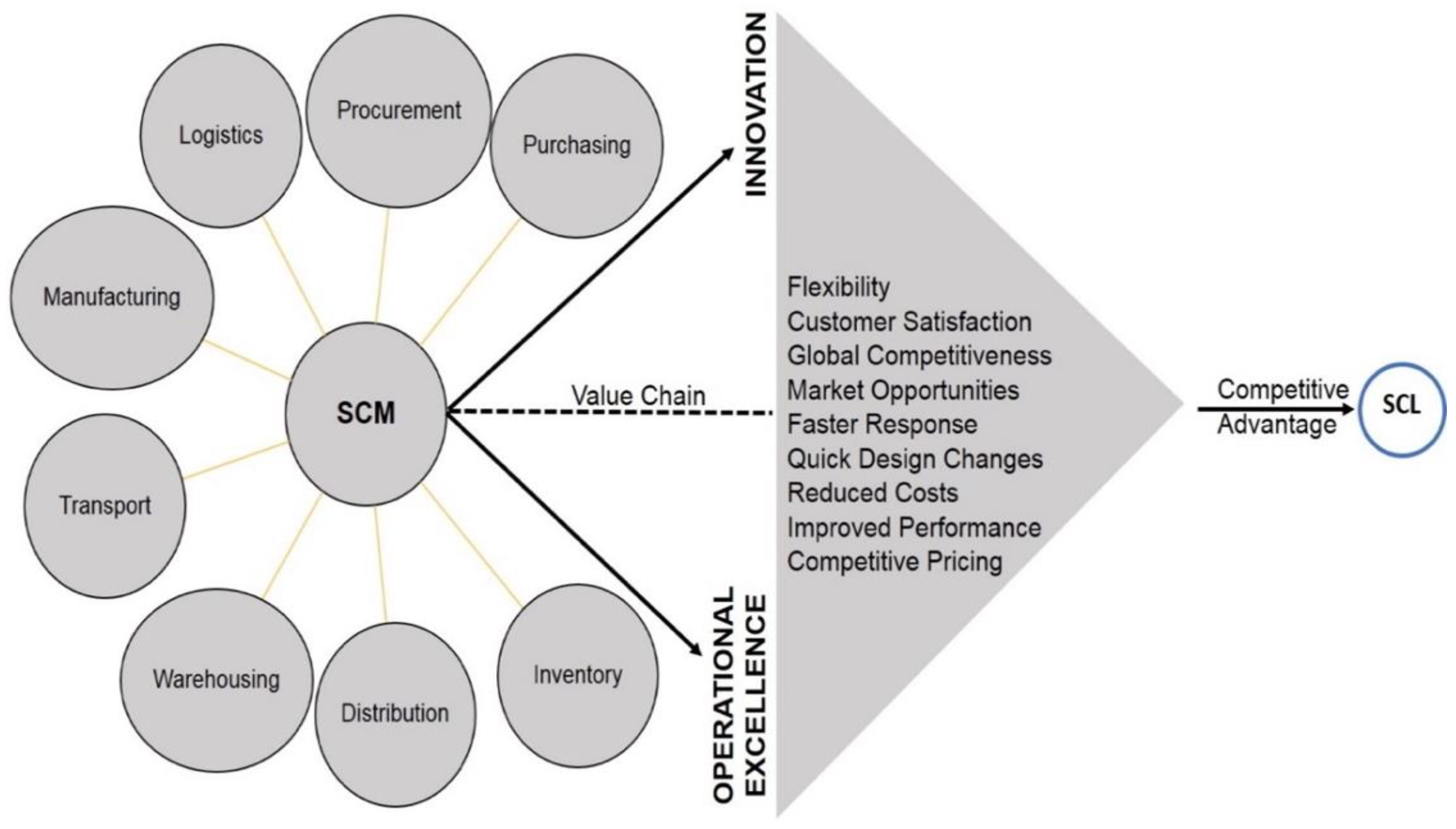

In addition, the conceptual framework for SCL about sustainable innovation and competitiveness in the context of a developing economy. The framework illustrates the incorporation of various activities in SCM such as purchasing, procurement, logistics, manufacturing, transportation, warehousing, distribution, and inventory management. Through operational excellence and innovation, the activities of SCM create a value chain that intensifies the competitiveness of a company in the form of flexibility, customer satisfaction, global competitiveness, market opportunities, faster response, quick design changes, reduced costs and improved performance as well as competitive pricing of products and services. Therefore, an enhanced competitive advantage through operational excellence and innovation of SCM activities creates SCL within a company (

Figure 6).

6. Conclusions

The study provided empirical insight for companies to understand and leverage on SCM strategic actions in a manner that influences their position on sustainable innovation in a developing economy for SCL. Companies should acknowledge the importance of sustainable innovation in the provision of products and services, considering the contribution of innovation towards SCM and SCL. However, innovation involves efforts of different important activities to be undertaken for it to succeed to the benefit of the company. It can be concluded that for SCL to be achieved in a developing economy about sustainable innovation, the actions related to innovation must be taken. In addition, the common characteristics and strategies for supply chain leaders must be prioritized for attention by the companies. The characteristics and strategies for SCM depend on the type of products or services that the company offers to the market. Given that the JSE-listed companies are multinationals, the characteristics, and strategies for SCM that were identified to be relevant for multinational companies include global forecast, awareness of uncertainties and environmental issues, understanding of the pull dynamic of the market, focus on directional leadership, top management involvement and R&D. furthermore, the creation of a separate SCM department apart from other functional departments; putting measures in place to enhance visibility, reliability and better coordination of functions; and management and resilience to overcome current and future economic challenges are also regarded as key strategies and characteristics for SCM in an environment of multinational companies such as the JSE-listed companies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Acquino, P.G. Jr. 2015. The effectiveness of leadership styles of managers and supervisors to employee’s job satisfaction in cooperative organizations in the Philippines. The Macrotheme Review, 4(5):18-28.

- Afraz, M.F., Bhatti, S.H., Ferraris, A. and Couturier, J. 2021. The impact of supply chain innovation on competitive advantage in the construction industry: Evidence from a moderated multi-mediation model. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 162, 120370. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.B., Lo, H.W., Gupta, H., Kusi-Sarpong, S., Liou, J.J. 2020. An integrated model for selecting suppliers on the basis of sustainability innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production. 277, 123261. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M., & Shah, S.Z.A. (2021). Entrepreneurial orientation and generic competitive strategies for emerging SMEs: Financial and non-financial performance perspective. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Aronow, S., Hofman, D., Burkett, M., Romano, J. & Nilles, K. 2014. The 2014 Supply Chain Top 25: Leading the decade. Supply Chain Management Review, 18(5), 8-17. https://www.scmr.com/article/the_2014_supply_chain_top_25_leading_the_decade.

- Baharum, F. 2012. The critical review on the Malaysian construction industry. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3(13):81-87.

- Barbuto, J.E. & Burbach, M.E. 2005. The emotional intelligence of transformational leaders: A Field study of elected officials. The Journal of Social Psychology, 146(1):51-64.

- Barett, P.T., Haug, J.C. & Gaskins, J.N. 2013. An interview on leadership with Al Carey, CEO, PepsiCo Beverages. Southern Business Review, 38(1):31-38. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/sbr.

- Bass, B.M. & Steidlmeir, P. 1999. Ethics, character and authentic transformational leadership behaviour. Leadership Quarterly, 10(2):181-127. [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, D.L. 2009. The relationship between transformational and transactional leadership of symphony orchestra conductors and organisational performance in US Symphony Orchestra. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Minneapolis, USA: Capella University.

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A., Hetland, J., Demerouti, E., Olsen, O.K. & Espevik, R. 2014. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1):138-157. [CrossRef]

- Brem, A. & Viardot, E. (2013). Evolution of innovation management: Trends in an international context. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, W.H. & Murray, S.L. (2010). Are companies continuously improving their supply chain? Engineering Management Journal, 22(4), 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Butner, K. 2010. The smarter supply chain of the future. Strategy & Leadership, 38(1):22-31. [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.C. 2009. Transformational leadership and pastoral leader effectiveness. Pastoral Psychology, 58(3):261-271. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H., Azevedo, S.G. & Cruz-Machado, V. (2012). Agile and resilient approaches to supply chain management: Influences on performance and competitiveness. Logistic Research, 4(1/2), 49-62. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D. 2014. Leadership in innovators and defenders: The role of cognitive personality styles. Industry and Innovation, 21(5):430-453. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A.Q. & Javed, H. (2012). Impact of transactional and laissez faire leadership style on motivation. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(7), 258-264. https://ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_7_April_2012/28.pdf.

- Covey, S. 2007. The transformational leadership report. Transformational Leadership Journal, pp. 1-19.

- Dansereau, F., Seitz, S., Chiu, C., Shaughnessy, B. & Yammarino, F.J. 2013. What makes leadership, leadership? Using self-expansion theory to integrate traditional and contemporary approaches. Leadership Quarterly, 24(6):798-821. [CrossRef]

- Dash, McMurtrey, Rebman & Kar, 2019. Application of artificial intelligence in automation of supply chain management. Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability, 14(3):43-53.

- Deans, L., Dership, L.E.A. & Rudd, R. 2008. Transactional, transformational, or laisses-faire leadership: An assessment of College of Agriculture academic program leaders’ (deans) leadership styles. Journal of Agricultural Education, 49(2):88-97.

- Ellinger, A., Shin, H., Northington, W.M., Adams, F.G., Hofman, D. & O’Marah, K. (2012). The influence of supply chain management competency on customer satisfaction and shareholder value. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17(3), 249-262. [CrossRef]

- George, L. & Sabhapathy, T. 2010. Work motivation of teachers: Relationship with transformational and transactional leadership behaviour of college principals. Academic Leadership: The Online Journal, 8(2):3-10. Retrieved from http://list.shaanan.ac.il/fl/files/567.pdf [Accessed 3 September 2018].

- Gosling, J., J, F., Yu Gong, Y., & Brown, S. 2016. The role of supply chain leadership in the learning of sustainable practice: toward an integrated framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 137:1458–69. [CrossRef]

- Greer, B.M. & Theuri, P. 2012. Linking supply chain management superiority to multifaceted firm financial performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 48(3):97–106. [CrossRef]

- Grosspietch, J. & Brinkhoff, A. (2009). Leadership in large supply chain projects. Supply Chain Magazine, September/October: 12.

- Hofman, D., Aronow, S. & Nilles, K. (2013). The Gartner Supply Chain Top 25 for 2013. Ninth edition. Stamford, USA: Gartner.

- Hohenstein, N.O. 2022. Supply chain management in the COVID-19 pandemic: strategies and empirical lessons for improving global logistics service provider’ performance. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 33(4): 1336-1365. [CrossRef]

- Hoveskog, M., Halila, F. & Danilovic, M. (2012). Business model innovation in the Chinese wind power industry: The case of Goldwind in the emerging economy of Africa. Halmstad: Centre of Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Learning Research, Halmstad University. [CrossRef]

- Janggaa, R., Alia, N.M., Ismaila, M. & Saharia, N. (2015). Effect of environmental uncertainty and supply chain flexibility towards supply chain innovation: An exploratory study. Procedia Economics and Finance, 31(15), 262-268. [CrossRef]

- Jia, F., Gong, Y. & Brown, S. 2019. Multi-tier sustainable supply chain management: The role of supply chain leadership. International Journal of Production Economics 217 (C): 44-63. [CrossRef]

- Kastelle, T. & Steen, J. (2011). Ideas are not innovations. Prometheus: Critical Studies in Innovation, 29(2), 199-205. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S. & Wright, J. (2013). Staying local or going global: Challenges for expansions into emerging markets. Logistic Management, (July), 48-50.

- Kim, J., Kim, K.H., Garrett, T.C. & Jung, H. (2014). The contributions of firm innovativeness to customer value in purchasing behaviour. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(2), 201-213. [CrossRef]

- Lii, P. & Kuo, F. 2016. Innovation-oriented supply chain integration for combined competitiveness and firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 174 (2016) 142–155. [CrossRef]

- Limsila, K. & Ogunlana, S.O. 2008. Performance and leadership outcome correlates of leadership styles and subordinate commitment. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 15(2):164-184. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. & Stephens, V. 2019. Exploring Innovation Ecosystem from the Perspective of Sustainability: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market and Complexity 2019, 5(3):1-14. [CrossRef]

- MacVaugh, J. & Schiavone, F. 2010. Limits to the diffusion of innovation: A literature review and integrative model. European Journal of Innovation Management, 13(2):197-221. [CrossRef]

- Malik, Y., Niemeyer, A. & Ruwadi, B. (2011). Building the supply chain of the future. McKinsey Quarterly, (January), 1-10. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/building-the-supply-chain-of-the-future.

- McCarthy, D.J., Puffer, S.M., May, R.C., Ledgerwood, D.E. & Steward, W.H. Jr. 2008. Overcoming resistance to change in Russian organizations: The legacy of transactional leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 37(3):221-235. [CrossRef]

- Mehrjerdi, Y.Z. (2009). Excellent supply chain management. Assembly Automation, 29(1), 52-60. [CrossRef]

- Milesi, D., Petelski, N. & Verre, V. (2013). Innovation and appropriation mechanisms: Evidence from Argentine microdata. Technovation, 33(2/3), 78-87. [CrossRef]

- Min, S., Zacharia, Z.G., & Smith, C.D. 2019. Defining Supply Chain Management: In the Past, Present, and Future. Journal of Business Logistics, 40(1):44-55. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, A.R.M., Genovese, A., Brint, A. & Kumar, N. 2019. Improving reverse supply chain performance: The role of supply chain leadership and governance mechanisms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 216 (2019) 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Muenjohn, N. & Armstrong, A. 2008. Evaluating the structural validity of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ): Capturing the leadership factors of transformational-transactional leadership. Contemporary Management Research, 4(1):3-14. [CrossRef]

- Nguni, S., Sleegers, P. & Denessen, E. 2006. Transformational and transactional leadership effects on teachers’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organisational citizenship behaviour in primary schools: The Tanzanian case. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2):145-177. [CrossRef]

- Pounder, J.S. 2008. Full-range classroom leadership: Implications for the cross-organizational and cross-cultural applicability of the transformational-transactional paradigm. Leadership, 4(2):115-135. [CrossRef]

- Prest, G. & Sopher, S. (2014). Innovations that drive supply chains. Supply Chain Management Review, 18(3), 42-49. https://www.scmr.com/article/innovations_that_drive_supply_chains.

- Rice, J. (2014). Inapt innovations can do more harm than good supply chain management. Supply Chain Management Review, 18(1), 10-11. https://ctl.mit.edu/sites/default/files/SCMR1401_InnovationStrategies_0.pdf.

- Rogers, E.M., Medina, U.E., Rivera, M. & Wiley, C.J. 2005. Complex adaptive systems and the diffusion of innovations. The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 10(3):1-26.

- Sabahi, S. & Parast, M. 2020. Firm innovation and supply chain resilience: a dynamic capability perspective. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 23(3):254-269. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A. and Pihie, Z.A. 2012. Transformational leadership and its predictive effects on leadership effectiveness. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(7):186-197.

- Sarkar, B., Takujeva, D., Guchait, R. & Sarkar, M. (2022). Optimised radio-frequency identification system for different warehouse shapes. Knowledge-Based Systems, 258(2022), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M.C., Den Hartog, D.N., Koopman, P.L. & Van Knippenberg, D. 2008. The role of transformational leadership in enhancing team reflexivity. Human Relations, 61(11):1593-1616. [CrossRef]

- Shamberger, D.K., Cleven, N.J. & Brettel, M. 2013. Performance Effects of Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation Strategies and the Moderating Role of External Innovation Partners. Industry and Innovation, 20:4, 336-356. [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S. & Tang, C.S. 2016. Supply chain opportunities at the bottom of the pyramid. Decision, 43(2):125-134. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40622-015-0117-x.

- Stank, T.S., Dornier, P., Petersen, K.J. & Srinivasan, M.M. (2015). Global supply chain operations: A region-by-region assessment of readiness. Supply Chain Management Review, 19(1), 16-18. https://www.scmr.com/article/global_supply_chain_operations_a_region_by_region_assessment_of_readiness.

- Stratman, T. (2010). Are supply chain leaders ready for the top? Supply Chain Management Review, 4(16), 28-33.

- Su, P. & McNamara, P. 2012. Exploration and exploitation within and across intra-organisational domains and their reactions to firm-level failure. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 24(1):129-149. [CrossRef]

- Sukati, I., Hamid., A.B.A., Baharum, R., Mdyusoff, R. 2012. The study of supply chain management strategy and practices on supply chain performance. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Science, 40185:227-233. [CrossRef]

- Tavanti, M. 2008. Transactional leadership. DePaul University. Retrieved from http://works.bepress.com/marcotavanti/15 [Accessed 6 July 2016].

- Vaio, A.D., & Varriale, L. 2019. Blockchain technology in supply chain management for sustainable performance: Evidence from the airport industry. International Journal of Information Management, 52 (2020) 1020. [CrossRef]

- Van Eeden, R., Cilliers, F., & Van Deventer, V. (2008). Leadership styles and associated personalities traits: Support for the conceptualisation of transactional and transformational Leadership. South African Journal of Psychology, 38(6):53-267. [CrossRef]

- Vokurka, R.J. (2011). Supply chain manager competencies. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 76(2), 23-37.

- Whittington, J.L., Coker, R.H., Goodwin, V.L., Ickes, W. & Murray, B. 2009. Transactional leadership revisited: Self-other agreement and its consequences. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(8):1860-1886. [CrossRef]

- Wrobleski, T. 2014. Rebalancing Act (2015): This year’s battle for supply chain’s life. Supply Chain Management Review, 18(7), 10-15. https://www.chainalytics.com/rebalancing-act-2015-this-years-battle-for-your-supply-chains-life/.

- Xenikou, A. & Simosi, M. 2006. Organizational culture and transformational leadership as predictors of business unit performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(6):566-579. [CrossRef]

- Xirasagar, S. 2008. Transformational, transactional and laissez-faire Leadership among physician executives. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 22(6):599-613. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A., & Soediantono, D. 2022. Supply Chain Management and Recommendations for Implementation in the Defense Industry: A Literature Review. International Journal of Social and Management Studies, 3(3):63–77. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, O., Gao, B. & Lugman, A. 2022. Linking green supply chain management practices with competitiveness during covid 19: The role of big data analytics. Technology in Society, 70, August 2022, 102021. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., Sosik, J.J., Riggio, R.E. & Yang, B. 2012. Relationships between transformational and active transactional leadership and followers' organizational identification: The role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Behavioural and Applied Management, 13(3), 186-212. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).