1. Introduction

As people's living standards continue to advance and their yearning for spiritual enrichment deepens, there is a burgeoning demand for engagement in outdoor sports activities. Outdoor sports represent a category of sports that occur in natural settings rather than specialized facilities and are characterized by an inherent spirit of adventure and experiential exploration [

1]. The core essence of outdoor sports lies in venturing beyond urban landscapes, connecting with nature, and participating in activities that involve an element of risk, challenge, and relevance. According to Rocher et al. [

2], engagement in outdoor sports has demonstrated substantial benefits for human health. Outdoor sports have proven effective in combating sedentary habits, leading to improved physical well-being, the promotion of healthier lifestyles, better stress management, and enhanced feelings of well-being [

3]. Consequently, governments worldwide actively encourage their citizens to engage in outdoor sports. Moreover, the growing community of outdoor sports enthusiasts can significantly contribute to expanding the outdoor sports market. Hence, investigating the determinants impacting individuals’ intention to continue participating in outdoor sports is of paramount importance and substantial value.

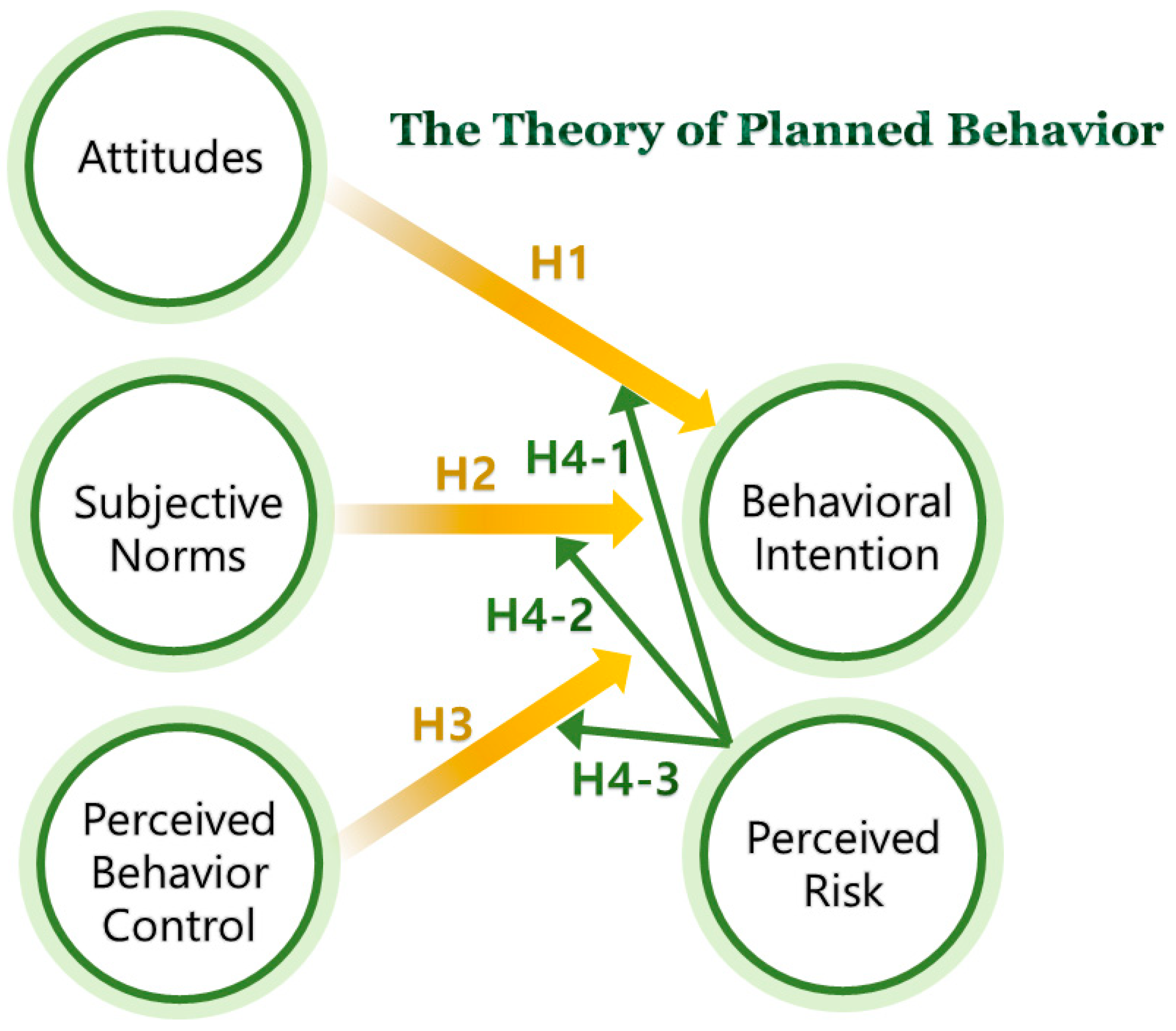

This study employs the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to examine the factors that positively influence the inclination to sustain participation in outdoor sports. TPB, an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), is one of the most widely recognized social-psychological frameworks for understanding human behavior [

4]. Since its introduction in 1991, the TPB has gained broad acceptance among researchers across diverse behavioral disciplines, including but not limited to healthy eating behavior, education, environmentally conscious consumerism, tourism, e-commerce, and sports marketing [

5]. Researchers in these domains have employed the theory to investigate the factors influencing both intentions and behavior [

6]. The TPB comprises three primary components: an individual’s attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms pertaining to the behavior, and perceived behavioral control (PBC). Collectively, these factors wield significant influence over an individual’s inclination to engage in a particular behavior [

6]. Consequently, this study aims to determine if attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC impact the intention to continue participating in outdoor sports.

To address gaps identified in prior TPB research and gain a deeper understanding of the psychology and behavior of amateur athletes, the present study examines how perceived risk related to particulate matter (or air pollution or brown smog) moderates the relationship among the variables under study. Recent reports in Korea have highlighted instances where particulate matter levels exceeded the daily air quality standard. Particulate matter consists of tiny particles invisible to the naked eye [

7] and is known to severely affect human health. According to a study by Kwak [

8], particulate matter triggers inflammation in the bronchial passages, leading to respiratory issues like chronic bronchitis, allergic rhinitis, and respiratory obstruction. Moreover, it can induce or worsen cardiovascular conditions such as stroke, heart attacks, and irregular heart rhythms. Consequently, individuals might be reluctant to engage in outdoor sports during periods of elevated particulate matter levels. Numerous studies have underscored the myriad advantages associated with outdoor sports, regardless of the presence of particulate matter [

9]. This study contributes to the existing literature by introducing the moderating variable of perceived risk of particulate matter into an established research model.

In line with the TPB, this study investigates the structural relationships between attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, and behavioral intention. Specifically, the emphasis is on the moderating effects of perceived risk associated with the particulate matter on the relationships between ‘attitudes and behavioral intention’, ‘subjective norms and behavioral intention’, and ‘PBC and behavioral intention’.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

Ajzen's [

10] Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), initially developed by Ajzen and Fishbein [

11], has garnered recognition in research for its efficacy in predicting behavioral intentions. This theory provides a framework for understanding human actions and the immediate motivations that drive them [

12]. According to Ajzen [

10], an individual's actions are fundamentally rooted in their behavioral intentions. In the TRA framework, intention is perceived as an individual's mental impetus to exert effort in engaging in a specific behavior [

13]. In line with the TRA, the behavioral intention is shaped by an individual’s attitudes toward the behavior and the influence of subjective norms.

Attitudes toward behavior pertain to an individual's overall assessment of engaging in a specific action. These attitudes are shaped by their fundamental beliefs about the potential outcomes of that behavior, known as behavioral beliefs. Behavioral belief represents an individual's personal perception of the likelihood that engaging in a particular behavior will lead to particular outcomes or result in a particular experience [

6]. For instance, wearing a mask (the behavior) can protect the body from particulate matter and viruses (the outcome), but it may also be perceived as causing difficulty breathing (the experience). Collectively, these behavioral beliefs are believed to generate either a positive or negative attitude toward the behavior [

6]. An individual's attitude toward a behavior tends to be positive when they anticipate favorable outcomes from engaging in that behavior [

14].

Subjective norms pertain to the degree to which individuals perceive social pressure when engaging in specific behaviors [

10]. These norms can be categorized into two categories: exemplary norms, which stem from interpersonal relationships such as family, friends, relatives, and colleagues, and injunctive norms, which are instituted by governmental authorities and employ social incentives to encourage specific actions or informal penalties to discourage others [

15]. Seonwoo & Jeong [

16] affirm that an individual’s intention to continue participating in sports is significantly shaped by the influence of their family, friends, relatives, supervisors, and colleagues. Hence, in the context of this study, subjective norms are closely associated with exemplary norms. Furthermore, subjective norms can be influenced by normative beliefs, which reflect the likelihood of influential figures expressing approval or disapproval of a particular behavior [

17].

Nonetheless, several researchers have highlighted limitations in the TRA, indicating its inadequacy in comprehensively explaining certain aspects of individuals' voluntary behaviors. For instance, individuals engaged in outdoor sports may encounter difficulties upholding their commitment when faced with time constraints stemming from frequent overtime or business trips. In response to these limitations and in accordance with the recommendations of researchers for expanding the TRA, Ajzen [

10] introduced the TPB, which incorporates a crucial additional element called Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC). PBC refers to an individual's perception of the ease or difficulty associated with performing a specific behavior [

10]. In essence, it assesses an individual's perception of their ability to manage factors that might constrain their actions in a given situation [

18]. For instance, when individuals have ample time, resources, and opportunities to navigate a challenging situation, their PBC is expected to be at its highest. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that PBC is influenced by control beliefs, encompassing an individual's perception of the prerequisites in terms of opportunities and resources necessary to execute a specific behavior [

19].

2.2. Perceived risk

Perceived risk is a crucial psychological factor in behavioral studies, significantly influencing an individual's attitude and response. It is defined as the extent of potential loss perceived by an individual [

20]. In essence, this concept encapsulates an individual's emotions and understanding of various external threats, highlighting the impact of personal experiences on intuitions and subjective perceptions [

21]. Perceived risk comprises multiple dimensions and can be evaluated through various indicators [

22]. According to Stone and Grønhaug [

23], perceived risk encompasses physical, psychological, financial, social, functional, and temporal dimensions. Psychological risk pertains to the likelihood of experiencing psychological harm when exposed to a hazard [

24]. Financial risk involves apprehensions about the potential loss of a specific monetary amount [

25]. Social risk is defined as ‘the likelihood of any unforeseen and unpredictable occurrence, beyond the individual's control, that results in a substantial decline in their quality of life or standard of living.’ Functional risk relates to concerns and doubts about external hazards interfering with an individual’s ability to execute a plan or engage in an activity. Lastly, time risk refers to the squandering or forfeiture of time due to poor choices or unforeseen circumstances [

26].

Within environmental studies, physical risks are frequently characterized by the tangible ramifications of environmental degradation and fluctuations in climate patterns. Environmental degradation poses a myriad of challenges, with contemporary concerns centered predominantly on the risks associated with particulate matter [

26]. Particulate matter can be categorized based on particle size, typically falling into the PM10 and PM2.5 categories. Notably, PM2.5 has been found to have a positive correlation with an array of deleterious health outcomes, affecting the respiratory system (e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), the cardiovascular system (e.g., ischemic heart disease, heart failure), the nervous system (e.g., dementia), cancer (e.g., lung cancer), and mortality, as reported by the EPA [

27]. Consequently, individuals harbor apprehension regarding the potential health consequences of particulate matter exposure, prompting them to alter their activity routines, including refraining from outdoor engagements [

28,

29]. Therefore, in the context of this study, outdoor sports participants can encounter an array of risks associated with particulate matter, and their unease concerning the unpredictable consequences can be termed their perceived risk.

2.3. Research Hypotheses development

There has been a growing emphasis on examining the impact of attitudes on behavioral intentions. For instance, a study conducted by Rajeh [

30] aimed to apply the TPB to identify factors that predict adults' intentions to enhance their oral health behaviors. The study revealed a positive and significant association between favorable attitudes and stronger intentions. Similarly, Pan and Liu [

31] studied the mask-wearing behavior of airline passengers during the COVID-19 pandemic, using the TPB model to investigate the correlation between nine predictive factors and passengers' intentions to wear masks in the aircraft cabin. The findings underscored the significant influence of attitudes on passengers’ intentions to wear masks during flights amid the pandemic. Furthermore, Wang and Tsai [

32] investigated the determinants influencing the behavioral intentions of elementary and junior high school teachers regarding school disaster preparedness. They employed the TPB as the theoretical framework and found a statistically significant direct impact of teachers' attitudes on their behavioral intentions. Thus, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H1:

Attitudes positively influence behavioral intention.

A substantial body of research has established a robust connection between subjective norms and behavioral intentions. For instance, a study by Jeong, Kim, and Yu [

33] investigated the decision-making process of sports enthusiasts during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, revealing the favorable impact of subjective norms on the intention to attend sports events. Carfora et al. [

34] conducted a psychological analysis focusing on the factors influencing attitudes toward and purchases of organic products using the TPB framework. Their findings indicated that subjective norms played a significant role in predicting the intentions of Italians to purchase organic milk. Furthermore, Yadav and Pathak [

35] delved into the factors that shape consumers' environmentally friendly purchasing behavior, demonstrating the supportive role of subjective norms in influencing consumers' intentions to opt for green products. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Subjective norms positively influence behavioral intention.

Existing research consistently demonstrates a positive correlation between PBC and behavioral intention. For instance, Lavuri [

36] investigated the factors that contributed to the propensity of millennials to purchase eco-sustainable products in emerging markets, revealing a statistically significant and positive effect of PBC on their purchasing intentions. A study by Zarei, Ehsani, Moghimehfar, and Aroufzad [

37] developed a robust model that comprehensively explains the formation of pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Their research revealed that PBC exerted a positive role in shaping behavioral intention. Similarly, Ateş [

38] sought to elucidate the determinants of pro-environmental behaviors within the framework of the TPB. The findings elucidated a direct impact of PBC on intentions to engage in pro-environmental actions. Consequently, the proposed hypothesis is:

H3:

Perceived behavioral control positively influences behavioral intention.

The concept of perceived risk, serving as a moderating factor, becomes evident when it influences the manifestation of behavioral intention. In the realm of tourism marketing, for example, individuals with lower risk perceptions exhibit a greater propensity to engage in repeat visits or recommend the destination to others compared to travelers with higher levels of perceived risk [

39]. In their seminal work, Campbell and Goodstein [

40] established the moderating effect of perceived risk on consumers' product assessments. Their research suggested that heightened risk perception tends to induce a more cautious consumer behavior, while reduced risk perception tends to make consumers more receptive to positive cues, resulting in more favorable product evaluations [

40]. Further research by Tavitiyaman and Qu [

41] examined the moderating role of perceived risk in shaping the connection between overall satisfaction and behavioral intention. Travelers who exhibited a reduced sense of risk associated with natural disasters tended to form a more favorable perception of the destination, experienced increased overall satisfaction, and exhibited a greater proclivity towards positive behavioral intentions. This was in contrast to those who perceived a higher level of risk. Building on this literature review, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H4-1:

Perceived risk moderates the influence of attitudes on behavioral intention.

H4-2:

Perceived risk moderates the influence of subjective norms on behavioral intention.

H4-3: Perceived risk moderates the influence of perceived behavioral control on behavioral intention.

Drawing from the existing body of literature, the present study employed the conceptual framework illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Method

3.1. Sampling and Date collection

We conducted a survey targeting amateur athletes who regularly participated in various outdoor sports activities such as running, golf, cycling, sailing, surfing, marathons, and skydiving. From early March to early April 2023, the researchers reached out to these athletes through a popular South Korean sports meet-up application. First, we explained the study’s purpose, nature, and survey methodology to the participants and obtained their consent. Subsequently, we were invited to join the group chat room of each meet-up, where we once again elaborated on the study details and shared a link for the Google Form survey. Participants expressed their consent by marking a “V” on the questionnaire and were informed of their right to discontinue the survey at any point. Consenting participants completed self-administered questionnaires. We employed a convenience sampling method, distributing a total of 270 questionnaires. We collected 252 valid responses for data analysis. The demographic characteristics included basic personal details such as gender (80.2% male and 19.8% female); age (28.6% aged 50 and above, 27% in their 40s, and 22.2% in their 20s and 30s); and education level (41.3% university graduates, 30.2% high school graduates, 15.1 with an associate degree, and 13.5% graduate degree holders).

3.2. Measure

The questionnaire included questions related to attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, perceived risk, and behavioral intention. All measurement scales used in this study were derived from established scholarly literature and had undergone rigorous validation in prior research investigations. Attitudes were assessed using three items adapted from Ajzen [

42] and Kim, Chung, Chepyator-Thomson, Lu & Zhang [

14]. The scales were ‘boring-exciting,’ ‘worthless-valuable,’ and ‘unpleasant-pleasant’, with interval scales ranging from 1 to 5. Subjective norms were assessed using three items from Ajzen [

42] and Yu & Jeong [

5]. PBC was assessed using three items adapted from Han, Meng, and Kim [

17] and Seonwoo and Jeong [

16]. The behavioral intention was assessed using three items from Seonwoo & Jeong [

16] and Yu & Jeong [

5]. Perceived risk was assessed using four items adapted from Kim, Kim, Jang, Cho, and Ha [

43] and Stenlund, Lidén, Andersson, Garvill, and Nordin [

44]. Responses were collected using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The content validity of the study instruments was assessed by a panel consisting of two experts in the sociology of sports and one specialist in environmental studies. These panelists evaluated the relevance, representativeness, and clarity of the items for each construct. Incorporating their valuable feedback, the initial questionnaire underwent refinements and enhancements, resulting in the final version used for dissemination. Furthermore, before administering the survey, requisite approval was sought and obtained from the university's Institutional Review Board.

3.3. Validity and Reliability

The This research utilized confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS to substantiate the structure of the measurement model. The goodness-of-fit indicators for the CFA, which included x²/df = 1.405, NFI = 0.968, RFI = 0.954, TLI = 0.986, and RMSEA = 0.039, consistently fell within the recommended thresholds as suggested by Hooper, Coughlan, and Mullen [

45].

This investigation computed factor loadings, construct reliability (CR), and the averaged variance extracted (AVE) to assess convergent validity based on the measurement model. As presented in

Table 1, all factor loadings (ranging from 0.815 to 0.967) exhibited statistical significance (p < 0.001) and exceeded the established threshold of 0.50, as recommended by Hair, Anderson, Babin, and Black [

46]. Furthermore, all CR values (ranging from 0.810 to 0.920) surpassed the requisite minimum of 0.7, and all AVE values (ranging from 0.588 to 0.792) surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.5, as proposed by Tabachnick and Fidell [

47]. Given that all CR and AVE values met or exceeded the prescribed criteria, the convergent validity of the measures was duly established.

To ascertain the adequacy of discriminant validity, it was imperative that the diagonal elements within

Table 2 exceed the off-diagonal elements, a condition that was indeed met. Furthermore, comparing all correlation coefficients with the square roots of AVE demonstrated a favorable level of discriminant validity.

Reliability assessments, measured by Cronbach's alpha, for the constructs of attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, behavioral intentions, and perceived risk (ranging from 0.893 to 0.964), all surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.7, affirming the robustness of the measurement instruments as per the guidelines outlined by Fornell and Larcker [

48] (refer to

Table 1 for details).

4. Results

4.1. Model fit and Structural Model

This study employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the proposed associations. All goodness-of-fit indicators for the model confirmed its acceptability (x²/

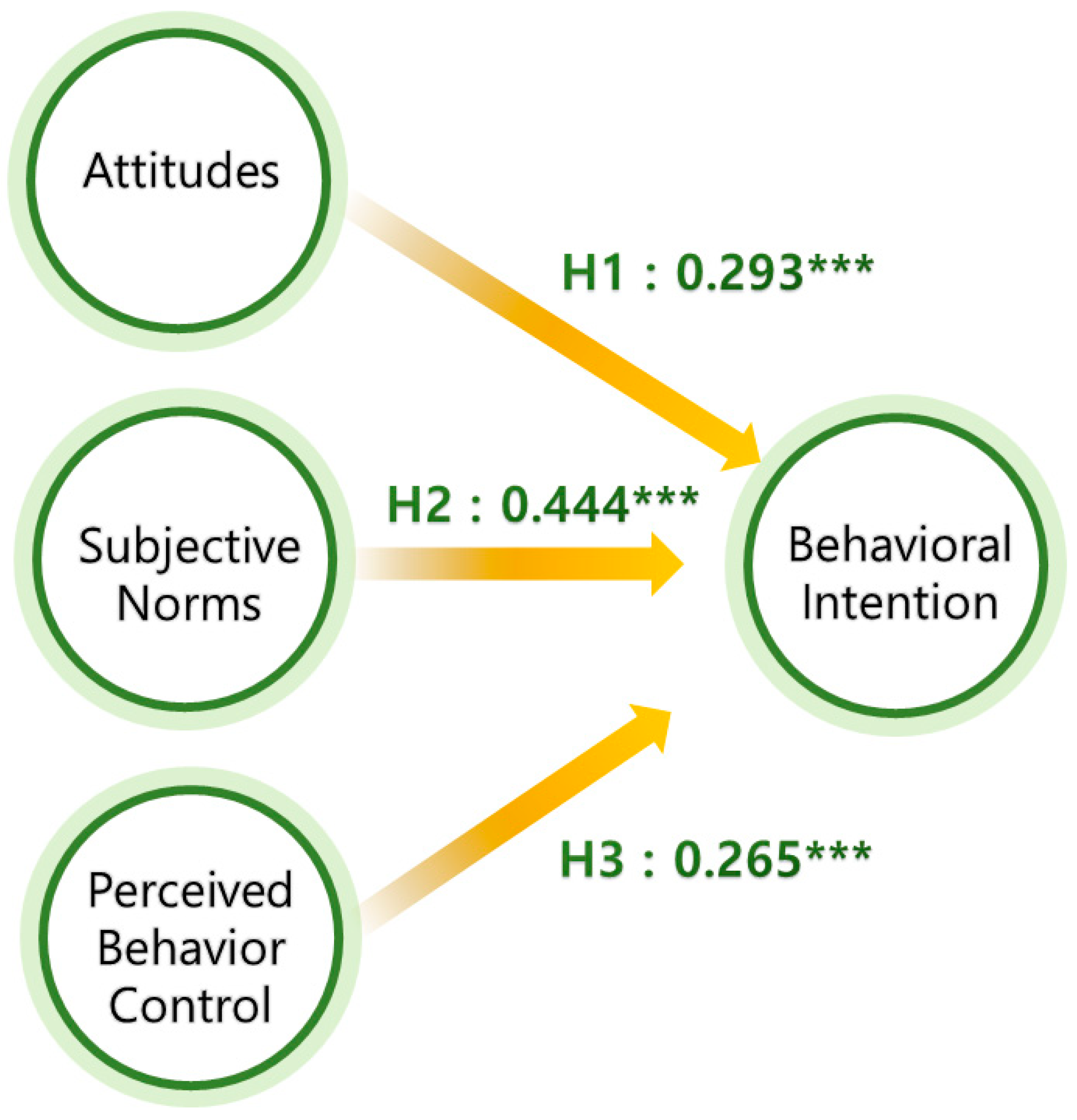

df = 1.322, NFI=0.980, RFI=0.968, CFI = 0.995, RMSEA = 0.036). This model served as the basis for testing hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. As depicted in

Figure 2, the association between attitudes and behavioral intention (H1) was found to be statistically significant (0.293,

p < 0.001). Notably, significant pathways were observed from subjective norms to behavioral intention (0.444,

p < 0.001), thereby supporting H2. Additionally, the effect of PBC on behavioral intention was significantly positive (0.265,

p < 0.001), thus reinforcing hypothesis H3.

4.2. Tests of Moderating effect

As hypothesized in H4-1, both attitudes (Z = 5.15,

p < 0.001) and perceived risk (Z = -2.57,

p < 0.05) exhibited significant effects on behavioral intention. However, their interaction did not yield a significant effect on behavioral intention (See

Table 3). Consequently, it can be concluded that perceived risk did not moderate the relationship between attitudes and behavioral intention. Thus, Hypothesis 4-1 was not supported.

As hypothesized in H4-2, subjective norms (Z = 8.664,

p < 0.001) had a significant effect on behavioral intention. However, perceived risk and its interaction with subjective norms did not demonstrate significant effects on behavioral intention (See

Table 3). Therefore, the perceived risk did not moderate the relationship between subjective norms and behavioral intention. Thus, Hypothesis 4-2 was not supported.

As hypothesized in H4-3, PBC (Z = 12.05,

p < 0.001) exerted a significant influence on behavioral intention. Perceived risk, on the other hand, did not demonstrate a significant impact on behavioral intention. However, it is important to note that their interaction (Z = -4.197,

p < 0.001) had a statistically negative effect on behavioral intention, thereby supporting H4-3 (See

Table 3). The independent variable exhibits a positive sign, the moderator variable demonstrates a negative sign, and their interaction also displays a negative sign, indicating the presence of a buffering effect. Subsequently, this study conducted a simple slope analysis to confirm the variations in the slope between the independent and dependent variables based on the moderating variable, categorizing the moderating variable into three groups: low (mean − 1SD), average, and high perceived risk (mean + 1SD). The results are shown in Figure 3. The analysis found that across all three groups (low, average, and high perceived risk), the variable of PBC had a significant effect on behavioral intention (Z = 12.05, 10.38, 8.85, respectively;

p < 0.001 in all cases). In Figure 3, it is evident that as one transitions from low to high clustering graphs, the slope gradually attenuates. This observation indicates that the moderating variable serves to diminish the impact of the independent variable.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical implications

The study’s findings underscore the direct and positive impact of subjective norms on shaping behavioral intentions. Engaging in outdoor sports demands significant time and financial resources and entails a higher risk of injury compared to indoor sports. Consequently, participants place substantial importance on the support and encouragement they receive from their loved ones. This support serves as validation for their decision to participate in outdoor sports, consequently amplifying their behavioral intentions. In the context of our study, it can be argued that harnessing social pressures stemming from the perceptions and expectations of others can effectively strengthen behavioral intentions, a conclusion that aligns with recent research findings. For instance, Ng [

49] extended the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to investigate the influence of risk perception on disaster preparedness behavior and identified subjective norms as a predictor of intention. Similarly, a study by Si, Duan, Zhang, Su, and Wu [

50] identified subjective norms as a determinant of individuals' intention to engage in water conservation.

Furthermore, while Ajzen [

10] asserts that attitudes are typically the most reliable predictors of intention, this study reveals that subjective norms have emerged as the most influential factor in forecasting behavioral intention—an outcome consistent with previous research where attitudes frequently occupied the primary predictive position. For instance, Kim and Hwang [

51] integrated the norm activation model and TPB to elucidate the formation of eco-friendly behavioral intentions and found attitudes to be the strongest predictor. Our study corroborates this in the realm of sports literature, as subjective norms exhibited the most substantial effect size, consistent with recent research in sports. For example, Yu & Jeong [

5] investigated the structural relationships among attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control (PBC), and career pursuit intentions among aspiring esport athletes. Their findings identified subjective norms as the most influential factor in predicting career pursuit intentions. This outcome underscores the pivotal role played by family and close friends in the decision-making process within the sports context.

The findings of this study revealed a significant association between attitudes and the intention to participate in outdoor sports, suggesting that individuals with more favorable views regarding outdoor sports are more likely to express an intention to participate. When individuals perceive outdoor sports as beneficial or enjoyable, whether based on past or current experiences, it naturally fosters a positive attitude toward participating in these activities. In essence, the relationship between a positive attitude and behavioral intention is likely mediated by positive experiences. This finding is in line with recent research. For instance, Lavuri [

52] investigated factors influencing millennials' purchasing intentions regarding eco-sustainable products and found a direct positive impact of millennial green attitudes on their purchase intentions. Similarly, Das et al. [

53] investigated the determinants of social distancing behavior during the COVID-19 outbreak, demonstrating that attitudes toward social distancing influenced the intention to adhere to social distancing measures. While the relationship between attitudes and behavioral intention is statistically significant, it is important to note that, in this study, attitudes do not emerge as the most potent predictor of intentions. Despite the strength of this association being surpassed by the relationship between subjective norms and behavioral intention, both attitude and subjective norms play significant roles in predicting behavioral intentions.

The findings illuminate the significance of PBC as an integral factor linked to behavioral intentions. While PBC exhibited the weakest correlation with behavioral intention compared to attitudes and subjective norms, it still displayed a positive and statistically significant relationship. This correlation underscores the pivotal role of individuals' perceptions about their abilities to engage in outdoor sports activities. Put simply, when participants in outdoor sports believe that they have sufficient resources to partake in these activities, their inclination to participate is strengthened. Conversely, doubts regarding the availability of opportunities, time, or financial means may undermine behavioral intention. In essence, the perceived level of ease or difficulty in engaging in outdoor sports can substantially influence behavioral intent.

Several researchers have underscored the importance of PBC in predicting behavioral intention. For instance, Raimondo, Hamam, D'Amico, and Caracciolo [

54] investigated the factors influencing millennials' intentions and behaviors related to reduced plastic consumption. Structural equation modeling revealed a significant influence of PBC in shaping the intention to reduce the use of plastic drinking bottles. Similarly, Parveen and Ahmad [

55] examined how individuals' intentions to consume environmentally friendly products, contributing to reduced urban air pollution, influenced their actual behavior. Their findings indicated that a higher level of PBC regarding the use of eco-friendly products predicted the intention to consume products with lower pollution levels. Consequently, the significance of PBC in enhancing the intent to participate in outdoor sports should not be underestimated.

The findings of the present study indicate that perceived risk serves as a moderator, influencing the relationship between PBC and behavioral intention. Specifically, this relationship tends to weaken for individuals with higher levels of perceived risk. In essence, the impact of PBC on behavioral intention is less pronounced among those who perceive particulate matter as a significant concern compared to those who perceive it as less severe. Individuals with heightened perceived risk may have had adverse experiences related to particulate matter or other forms of environmental pollution. Particulate matter is associated with health issues such as allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, respiratory problems, otitis media, hair loss, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Consequently, those who have experienced these health issues may exhibit greater sensitivity to particulate matter and potentially harbor reservations about participating in outdoor sports. These findings underscore the paramount importance of considering particulate matter in the context of outdoor activities.

Furthermore, while prior research has explored the relationships between perceived risk and attitudes [

56,

57], there has been a dearth of comprehensive investigations into the moderating role of perceived risk within the framework of the TPB. Our study systematically explores these moderating effects of perceived risk, shedding light on its role in modulating the relationship between PBC and behavioral intention. This scholarly contribution offers novel insights into the concept of perceived risk. Given the evident significance of perceived risk regarding particulate matter in predicting behavioral intention, it is imperative for future research endeavors to prioritize in-depth exploration of its impact.

5.2. Practical implications

The findings of this investigation bear significant implications as they can serve as a catalyst for raising public awareness regarding the health risks linked to particulate matter, an issue of paramount societal importance. It is pertinent to note that despite the general awareness among the public about the risks posed by particulate matter during outdoor physical activities, both national and local governmental entities have yet to implement sufficiently robust protective measures. This lack of comprehensive protective measures exacerbates the health risks faced by individuals. Consequently, an immediate and pressing need exists for the implementation of enhanced protective measures and the promotion of increased awareness concerning the perils associated with particulate matter, as underscored by Choi and Bum [

9]

In the pursuit of mitigating the presence of particulate matter, it is incumbent upon both national and local governments to undertake several essential initiatives: 1) Significantly Reduce Diesel Vehicle Numbers and Promote Public Transportation: A pivotal measure involves a substantial reduction in the population of diesel-powered vehicles, a known source of particulate matter emissions. Concurrently, there should be a concerted effort to invigorate public transportation systems. 2) Drastically Curtail Coal Power Plants: It is imperative to halve the number of coal power plants, given their role as a prominent contributor to particulate matter emissions. 3) Enforce Stringent Regulations on Particulate Matter Emissions from Corporations: Robust management of particulate matter emissions from corporate entities is essential to curbing their prevalence. 4) Improve Energy Efficiency and Embrace Renewable Energy Sources: Measures should be taken to enhance energy efficiency and expand the adoption of renewable energy sources, thereby reducing reliance on sources that contribute to particulate matter. 5) Establish Collaborative Reduction Targets: National and local authorities should collaborate to set reduction targets and commit to a collective effort to mitigate particulate matter levels. By diligently pursuing these comprehensive measures, governments can significantly contribute to reducing particulate matter levels and, in turn, safeguarding public health.

Sports companies and participants have proactively engaged in a spectrum of initiatives aimed at mitigating particulate matter. These are: 1) Promoting eco-friendly Transportation: Encouraging individuals to opt for walking as an eco-conscious mode of transportation when traveling to nearby sports venues. 2) Minimizing Vehicle Idling: Advocating against prolonged idling while driving, thereby reducing emissions that contribute to particulate matter. 3) Optimizing the Indoor Environment: Ensuring that indoor sports facilities are maintained at an appropriate heating temperature, typically 20 degrees Celsius. This measure serves the dual purpose of minimizing energy consumption and emissions. 4) Greening Outdoor Spaces: Initiating programs for planting foliage in outdoor sports facilities to improve air quality and create a more pleasing environment. 5) Sustainable Equipment Choices: Promoting the responsible use of plastic materials in acquiring sports equipment and adopting reusable grocery bags, aligning with sustainability objectives. These collective efforts not only contribute significantly to the reduction of particulate matter but also enhance the overall safety and enjoyment of outdoor sports activities in an environment characterized by fresh, clean air.

6. Conclusion

This study, rooted in the theoretical framework of the TPB, explores the structural connections among attitudes, subjective norms, PBC, and behavioral intention. Specifically, our investigation explores the moderating influence of perceived risk related to particulate matter on the associations between 'attitudes and behavioral intention,' 'subjective norms and behavioral intention,' and 'PBC and behavioral intention' within the context of individuals engaged in outdoor sports. Data were collected from outdoor sports gatherings organized through a prominent sports meetup application in South Korea. We employed confirmatory factor analysis to establish the construct validity of the measurement scale, assess factor loadings, averaged variance extracted (AVE), and construct reliability (CR). The measurement scale's reliability was further confirmed using Cronbach's α analysis. To fulfill our research objectives, we leveraged structural equation modeling with maximum likelihood estimation to investigate the examined positive relationships. Additionally, moderation analysis was conducted using the statistical software Jamovi. The findings underscore the significant impacts of attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC on behavioral intention, while also revealing that perceived risk exerts a moderating effect, influencing the relationship between PBC and behavioral intention. Therefore, the government will need to exert substantial efforts to mitigate particulate matter levels.

Notwithstanding the valuable contributions of this study, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations that merit consideration in future research endeavors. Firstly, this investigation did not explore the antecedents of attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC. Existing scholarship has revealed the potential influence of various factors on these key determinants of behavioral intention. Therefore, it is incumbent upon future studies to scrutinize these potential antecedents, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the underpinnings of attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC. Secondly, a noteworthy opportunity exists to explore additional moderating factors that may further enrich the theoretical framework. Investigating potential moderating factors would equip researchers with deeper insights into the complexities of the relationships among the core constructs, ultimately enhancing the model's predictive power. Lastly, it is imperative to acknowledge that the current study was conducted within the context of South Korea. Consequently, the findings may not be universally applicable to other countries or cultural settings. Cultural nuances and contextual differences can profoundly influence the validity and generalizability of research outcomes. Therefore, it is both pertinent and valuable to extend the examination of the model to diverse cultural settings, ensuring that its applicability transcends national boundaries and offers relevant and adaptable insights to various sociocultural contexts. This approach contributes significantly to the robustness and external validity of the research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y. Jeong and Y.Y.; methodology, Y. Jeong; software, Y. Jeong; validation, D. Kim.; formal analysis, Y. Jeong; investigation, D. Kim; resources, D. Kim; data curation, Y. Jeong; writing—original draft preparation, D. Kim; writing—review and editing, Y. Jeong; visualization, Y. Jeong; supervision, Y. Jeong; project administration, D. Kim; funding acquisition, D. Kim.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Korea National University of Transportation

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kong, D.; Sun, J. Study on the countermeasures of integrating outdoor sports into the development of health service industry in China. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocher, M.; Silva, B.; Cruz, G.; Bentes, R.; Lloret, J.; Inglés, E. Benefits of outdoor sports in blue spaces. the case of School Nautical Activities in Viana do Castelo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puett, R.; Teas, J.; España-Romero, V.; Artero, E. G.; Lee, D. C.; Baruth, M.; ... & Blair, S. N. Physical activity: does environment make a difference for tension, stress, emotional outlook, and perceptions of health status? Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 2014; 11, 1503–1511.

- Ulker-Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. G.; Jeong, Y. A Case Study of Factors Impacting Aspiring E-sports Athletes in South Korea. Studia Sportiva 2022, 16, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.H. Die rechtliche Untersuchung uber Feinstaub fur den Schutz des Gesundheitsrechts der Burger. Korean Environmental As¬sociation 2016, 38, 159–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, K. Invasion of fine dust, disease and coping methods. Retrieved 04/23, 2019, from http://www.civicnews.com/news/articleView.htm¬l?idxno=21216.

- Choi, C.; Bum, C. H. Public perception of fine dust: a comparative research of participation motives in outdoor physical activities depending on fine dust concentration. Sport Mont 2019, 17, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980.

- Arkorful, V. E.; Hammond, A.; Lugu, B. K.; Basiru, I.; Sunguh, K. K.; Charmaine-Kwade, P. Investigating the intention to use technology among medical students: An application of an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Public Affairs 2022, 22, e2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In ction control: From cognition to behavior; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Chung, K. S.; Chepyator-Thomson, J. R.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, J. J. The LPGA’s global tour and domestic audience: Factors influencing viewer’s intention to watch in the United States. Sport in Society, 2020; 23, 1793–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Si, H.; Duan, X.; Zhang, W.; Su, Y.; Wu, G. Are you a water saver? Discovering people's water-saving intention by extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 311, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seonwoo, Y. Y.; Jeong, Y. D. Exploring factors that influence taekwondo student athletes’ intentions to pursue careers contributing to the sustainability of the Korean Taekwondo Industry using the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability, 2021, 13, 9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L. T. J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tourism Management 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V. K.; Chandra, B. An application of theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers' green hotel visit intention. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. K. Predicting unethical behavior: a comparison of the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 1998, 17, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R. A. Demystifying the effects of perceived risk and fear on customer engagement, co-creation and revisit intention during COVID-19: A protection motivation theory approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2021, 20, 100564. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhu, S.; Xue, H.; Chen, F. Online purchase intention of fruits: Antecedents in an integrated model based on technology acceptance model and perceived risk theory. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, X. The impact of perceived risk on consumers’ cross-platform buying behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 592246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R. N.; Grønhaug, K. Perceived risk: Further considerations for the marketing discipline. European Journal of Marketing 1993, 27, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, Y.; Yoo, J. L.; Yue, G.; Yu, J. Can the perceived risk of particulate matter change people's desires and behavior intentions? Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 1035174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, E. Y. The effect of perceived risk on online shopping in Jordan. European Journal of Business and Management 2013, 5, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Park, Y.; Yoo, J. L.; Yue, G.; Yu, J. Can the perceived risk of particulate matter change people's desires and behavior intentions? Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 1035174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA. Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Particulate Matter, 2019.

- Keiser, D.; Lade, G.; Rudik, I. Air pollution and visitation at US national parks. Science Advances, 2018, 4, eaat1613. 2018, 4, eaat1613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Duarte, F.; Wang, D.; Zheng, S.; Ratti, C. Exploring the effect of air pollution on social activity in China using geotagged social media check-in data. Cities 2019, 91, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeh, M. T. Modeling the theory of planned behavior to predict adults’ intentions to improve oral health behaviors. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J. Y.; Liu, D. Mask-wearing intentions on airplanes during COVID-19–Application of theory of planned behavior model. Transport policy 2022, 119, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. J.; Tsai, N. Y. Factors affecting elementary and junior high school teachers’ behavioral intentions to school disaster preparedness based on the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2022, 69, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. K.; Yu, J. G. Examining the process behind the decision of sports fans to attend sports matches at stadiums amid the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: The case of South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Cavallo, C.; Caso, D.; Del Giudice, T.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; ... & Cicia, G. Explaining consumer purchase behavior for organic milk: Including trust and green self-identity within the theory of planned behavior. Food Quality and Preference 2019, 76, 1–9.

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G. S. Determinants of consumers' green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecological Economics 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. Extending the theory of planned behavior: factors fostering millennials’ intention to purchase eco-sustainable products in an emerging market. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2022, 65, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, I.; Ehsani, M.; Moghimehfar, F.; Aroufzad, S. Predicting Mountain Hikers' Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention: An Extension to the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Park & Recreation Administration 2021, 39, 70–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, H. Merging theory of planned behavior and value identity personal norm model to explain pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2020, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A. A macro analysis of the relationship of product involvement and information search: the role of risk. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2000, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M. C.; Goodstein, R. C. The moderating effect of perceived risk on consumers' evaluations of product incongruity: Preference for the norm. Journal of Consumer Research 2001, 28, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Qu, H. Destination image and behavior intention of travelers to Thailand: The moderating effect of perceived risk. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2013, 30, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a theory of planned behavior questionnaire. http://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2022, 2006.

- Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Jang, B.; Cho, D.; Ha, J. (2022). The effect of indoor sports planning behavior theory on behavioral intention by parents of childhood sports participants’ perception of the risk fine dust. Korean Society for The Study of Physical Education 2022, 27, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenlund, T.; Lidén, E.; Andersson, K.; Garvill, J.; Nordin, S. Annoyance and health symptoms and their influencing factors: A population-based air pollution intervention study. Public Health 2009, 123, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal Business Research Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F.; Anderson, R. E.; Babin, B. J.; Black, W. C. Multivariate data analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. G.; Fidell, L. S. Experimental designs using ANOVA; Duxbury Press,: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S. L. Effects of risk perception on disaster preparedness toward typhoons: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2022, 13, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Duan, X.; Zhang, W.; Su, Y.; Wu, G. Are you a water saver? Discovering people's water-saving intention by extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 311, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. J.; Hwang, J. Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. Extending the theory of planned behavior: factors fostering millennials’ intention to purchase eco-sustainable products in an emerging market. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2022, 65, 1507–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A. K.; Abdul Kader Jilani, M. M.; Uddin, M. S.; Uddin, M. A.; Ghosh, A. K. Fighting ahead: adoption of social distancing in COVID-19 outbreak through the lens of theory of planned behavior. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 2021, 31, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, M.; Hamam, M.; D'Amico, M.; Caracciolo, F. Plastic-free behavior of millennials: An application of the theory of planned behavior on drinking choices. Waste Management 2022, 138, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, R.; Ahmad, A. Public behavior in reducing urban air pollution: An application of the theory of planned behavior in Lahore. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2020; 27, 17815–17830. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Lin, H. N.; Liu, Y. P. Predicting the use of pirated software: A contingency model integrating perceived risk with the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 2010, 91, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K. L.; Sia, J. K. M.; Tang, K. H. D. Examining students’ behavior towards campus security preparedness exercise: The role of perceived risk within the theory of planned behavior. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 4358–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).