1. Introduction

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), around 1.45 billion people visited foreign countries in 2019. Global tourism spending was estimated at $1468 billion, generating 334 million jobs, making it one of the world’s largest economic sectors. As a consequence of the global COVID-19 pandemic, these figures plummeted over the next two years, and countries heavily reliant on tourism suffered a significant decline in economic activity, which also led to a reduction in the externalities generated by the overexploitation of tourism resources. In this sense, the post-pandemic scenario represents an opportunity for countries to undertake the required reforms to achieve more sustainable tourism development.

Global concern about the state of the environment and the need for sustainable practices in all aspects of life has grown in recent years. The tourism industry has witnessed an important transition towards sustainable tourism as visitors become more aware of their impact on the places they visit. In this regard, attitudes towards the environment are crucial in shaping preferences for sustainable tourism, influencing travellers’ behaviour and processes (Karampela et al., 2021; Maltese & Zamparini, 2022; Xu & Fox, 2014).

In particular, one of the most interesting trends observed in recent decades has been the shift from vacationing for relaxation and recreation to more health and quality-of-life-related vacation experiences, which include more sports and adventure activities. The UNWTO predicted that active and adventure travel related to nature and culture would be one of the primary sources of tourism revenue growth (Honey, 1999). According to De Knop (1990), "sports and active recreation during the holiday has become very successful, probably due to increased urbanization and of changing leisure time pursuit". Sport’s significance in tourism can also be seen in the scientific context, where academics have increasingly integrated the two disciplines into a scientific theme. Sport & Tourism, a scientific journal founded in 1993, exemplifies this trend.

This article aims to contribute to the academic understanding of consumer behaviour and the environmental attitudes that underpin sustainable tourism choices. In particular, the study analyses how attitudes toward the environment influence preferences and willingness to pay for sustainable tourism products on the Spanish island of Gran Canaria. The analysis consists of integrating these attitudes, represented by a set of latent variables, into a choice model and focuses on a market segment comprised primarily of potential customers who are young residents and non-residents with a strong interest in nature tourism. The sample ensures a certain homogeneity in the researched group in terms of common interests as well as similar budgetary constraints.

Although the island is best known for being a popular year-round mass tourism destination, it also offers many landscapes and microclimates. It is often referred to as a miniature continent. These features enable visitors to participate in a variety of tourism and sports activities that are more environmentally friendly. Beach activities, mountain and water sports, as well as cultural activities are among them. A year-round warm climate, with an average monthly temperature of 20 degrees Celsius (Börjes, 2008), contributes to this.

Gran Canaria is dominated by hotel and mass tourism, which often has adverse effects on environmental and social issues, such as pollution and a decrease in the quality of life of the local residents. Therefore, a thorough understanding of consumer preferences in this context would be highly beneficial to promote active, more nature-based, eco-friendly and environmentally sustainable tourism activities. This allows Gran Canaria and other tourist destinations to promote alternative forms of tourism that benefit nature, culture and the local population.

Nature-based tourism has the potential to offer sustainable tourism products that are different from the traditional mass tourism products based on sun, sea, and sand (3S). Gran Canaria is a famous destination in the EU for such mass tourism products, but it is essential to develop alternative sustainable tourism products. Nature-based tourism developments require specific environments where certain activities and attractions can be marketed to particular segments (Giddy & Webb, 2018). Tourists’ environmental attitudes significantly influence their preferences, but limited literature on this topic exists. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by analysing how environmental attitudes, categorised into three latent variables: community support, nature interaction, and nature connection, shape nature-based tourists’ preferences. In addition, the WTP figures are indirectly obtained from model parameters, contributing to the scarce research on understanding pro-sustainable behaviour and its influence on the economic implications (Pulido-Fernández & López-Sánchez, 2016). The study also investigates the development of a potential commercial tourist area in Veneguera, a protected natural space located in the south of Gran Canaria that is rich in natural resources running along a beautiful ravine and pristine coastline.

2. Literature Review

Growing environmental concerns and increased ecological awareness have impacted consumer habits worldwide. Budeanu (2007) contended that a limited understanding of the dynamics between different determinants of tourists’ sustainable behaviour could hinder the tourists’ choices of more sustainable alternatives. In addition, assessing tourist demand, motivations, preferences, and willingness to pay (WTP) an extra premium for more sustainable tourist alternatives is crucial for investors and operators interested in developing environmentally friendly tourist products that promote nature conservation and more sustainable tourist consumption (Cordente-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Wahnschafft & Wolter, 2023).

Tourists’ choices are influenced by promoting their behaviour towards more sustainable options in the whole chain of the tourism industry (Verma & Chandra, 2018). The Faculty of Medicine and Psychology at the Sapienza University of Rome found that biospheric values, positive attitudes toward sustainable tourism, and higher levels of affinity toward diversity can predict more sustainable tourism choices, while personality traits play a more indirect role (Passafaro et al., 2015). Several studies also found connections between environmental attitudes and sustainable tourism choices. An extensive review of studies can be consulted in Passafaro (2020).

Different modelling approaches are used in the literature to analyse this connection from qualitative, quantitative and triangulation methods, smart partial least squares, exploratory factor analysis, structural equation models, latent variable methods and discrete choice methods. After reviewing fifty-nine papers that analyse this connection, we deduce that one of the methods that has been more used in the last decade is the smart partial least squares method. Nevertheless, hybrid choice models like the one used in this study have not been so commonly used.

For example, Sultana et al. (2022) found, using a Partial Least Square method (PLS), a significant positive influence of perceived green knowledge and green trust on customers’ intention to visit green hotels in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Nowacki et al. (2021) use a similar PLS approach to find significant relationships between attitudes towards the environment, an eco-friendly destination, social and personal norms and behavioural control, with intentions to travel to eco-destinations. However, the same study also found a very weak relationship between positive attitudes towards environmentally friendly destinations and the willingness to pay a premium for a more environmentally conscious trip. Thus, the authors found that even though tourists have a positive attitude towards sustainable tourism, only some of them are willing to pay higher prices for sustainable tourism purchases, green transport choices and responsible behaviour in the destinations.

Pinho & Gomes (2023) also used a PLS model to demonstrate the existence of a dissonance between the tourists’ interest in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and their behaviour when they are travelling. Thus, the authors showed that most of the Portuguese participants were interested in choosing a sustainable destination, but on the other hand, they did not show the same interest in preserving the sustainability of the destinations or in demonstrating pro-environmental habits. Wahnschafft and Wolter (2023) used a triangulation approach to find that a small extra willingness to pay existed for more sustainable excursions on environmentally friendly tourist boats in the context of solar-battery-electric boats cruising the Spree River in downtown Berlin. During interviews, several passengers expressed their desire for a more sustainable form of boat excursion, even if it meant paying a higher price. All customer groups were willing to pay the extra premium regardless of their preferences, motivations, consumption patterns, and interests.

Moreover, other studies are inconclusive and find different tourist segments that support sustainable tourism development. Puciato et al. (2023) used a systematic literature review and found that tourists with higher levels of education and financial status, as well as younger travellers, are more likely to accept higher prices for sustainable services. Pulido-Fernández and López-Sánchez (2016) also found different segments investigating if tourists are willing to pay extra premiums for sustainable destinations. To that aim, the authors used a logistic regression model to show that tourists with more level of commitment, attitude, knowledge, and behaviour regarding sustainability, named pro-sustainable tourists, are willing to pay more to visit sustainable destinations in the Costa del Sol, Spain. However, at the same time, there is also an important segment which is reluctant to pay the extra premium.

Sultana et al. (2022) highlighted the need to study the young generation because this segment will be the largest group of travellers in the future. The authors used a PLS model to find a significant positive influence of perceived green knowledge and trust on customers’ green hotel visit intention. Gan and Nuli (2018) also studied young tourists’ sustainable choices, finding that environmental awareness was an important driver of Millennials’ willingness to pay for green hotels. However, the Malaysian millennials’ green hotel demand must be viewed in the context of a relatively low environmental awareness compared to the current study.

Nowacki et al. (2023) found that the perceived green image of a destination has the strongest impact on Gen Z´s intention to travel to a destination and that this perception has more impact than the pro-environmental attitudes towards green tourism and personal norms. They concluded that the WTP an extra premium are more significant for Gen Z than for other generations. The authors also showed the existence of intercultural differences among Indians and Poles and challenged other researchers to contribute shedding more light on this topic using other destinations and cultural groups.

Campos-Soria et al. (2021) used a hierarchical linear model to show that tourists’ environmental concerns are influenced not only by individual and travel-related factors but also by their place of residence. The authors found that the different trends observed in European countries are mainly due to differences in economic, cultural, and environmental factors and that such between-country differences mainly explain the heterogeneous pattern. Frank et al. (2015) also found some country differences in analysing the nature-based (surf) products in the Algarve, Portugal. The study found that the WTP is related to nationality, with respondents from Germany, Austria and Switzerland showing higher WTP figures. Nevertheless, contrary to the current study, WTP figures were directly obtained by the questionnaire, which usually offered biased and less accurate results (Hole & Kolstad, 2012).

The section ends with studies that used latent variables and hybrid choice models that have been recently applied in tourism. As previously said, the literature is still scant. For example, Albadalejo and Díaz-Delfa (2021) analysed the rural accommodation choice process using a hybrid discrete choice (HDC) that take into account latent motivation variables through a multiple indicator multiple cause (MIMIC) model. The results showed that motivations affected the rural accommodation choice and interacted with other attributes that depend on the accommodation characteristics. In a similar fashion, Masiero and Hrankai (2022) analysed the transport modal choice of some urban destinations studying the less visited peripheral uncongested areas. The authors provided a methodological framework based on tourist accessibility for peripheral urban attractions. A discrete choice experiment was designed to investigate latent variables according to different types and ratings of tourist attractions and the main characteristics of mass public and private transport alternatives. The authors estimated a hybrid choice model finding that repeat visitation, length of stay and public transport system perceptions were determinants in the tourists’ modal choice. Song et al. (2023) also used a hybrid choice model to investigate low-carbon footprint travel choices, considering as latent variables both destinations and climate change perceptions. The authors also examined the impacts of nudging altering tourists’ behaviour that mitigated the carbon footprint in destinations. The study found that the destination type, carbon emissions and travel cost had significant effects on tourists’ choices of destinations, and nudging was a great tool to reduce the tourists’ carbon footprint. Tourists who were more aware of climate change were more likely than others to select low-carbon destinations.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Choice Experiment

The data set used in the analysis is obtained from a discrete choice experiment (DCE), which allowed us to determine individuals’ preferences and willingness to pay for various active tourism activities. The DCE was integrated into a questionnaire with attitudinal questions and a section for gathering socio-demographic data. Other sections of the questionnaire were not used in the present research.

DCEs represent an adequate data collection tool that is very helpful in understanding how individuals make decisions. Since the method generates hypothetical choice scenarios, they are handy for analysing the demand for alternatives that have not yet been marketed (Bliemer & Rose, 2006). Moreover, DCEs have a solid theoretical foundation anchored in the discrete choice theory (McFadden, 1981) and have emerged as a vital instrument in various areas such as transportation, health, and environmental research.

Some popular outdoor activities are investigated in our experiment where tourists can explore rural lifestyles and interact with rural communities. These activities will take place in Veneguera, Gran Canaria, declared a protected natural space in 2003, rich in natural resources, that runs along a stunning ravine and a pristine coastline. When choosing the activities, those that could be addressed to a large audience were considered and those that could be implemented in the natural space under investigation. As a result, the tested attributes include active hiking trails that include visits to some natural spots, such as the "Blue Pools of Veneguera"; a more culturally oriented version of hiking; and guided group activities such as snorkelling/scuba diving and star gazing. The lodging type and the vacation package cost were also considered. The activities included in the experiment followed Pesonen’s categorization of rural tourism clusters, which include active, passive, nature, and aquatic activities (Pesonen, 2015). According to this author, activity segmentation is a more useful segmentation approach than using travel motivations to reach different market segments.

In the choice experiment, respondents answered twelve choice scenarios defined by two hypothetical active tourism packages and a non-choice alternative. The choice scenarios were obtained by combining the different levels of the attributes considered in the analysis through an efficient design built using the software Ngene (Choicemetrics, 2009). The definition of the attributes’ levels is shown in

Table 1. Thus, the alternative chosen by the individual would be regarded during the modelling process as the one that maximises his utility based on the behavioural rule of utility maximisation.

The experiment consisted of 12 choice scenarios, so each participant provided 12 statistical observations. A total sample of 476 individuals was collected, generating 5712 valid observations for model estimation. The sample was evenly distributed by gender and between Gran Canaria residents and non-residents, with a slightly higher proportion of active workers (53.3%). Sampled individuals had an average age of 23.6 years and a monthly income of 481 euros. The non-resident sample was drawn from participants in a summer sports camp in a small village in the southwest of France and was primarily made up of Germans. Residents’ sample was mainly obtained from university students randomly recruited in different campus locations. Trained interviewers completed all the questionnaires through face-to-face interviews to ensure the quality of the information obtained.

The attitudinal questionnaire included nine items or indicators related to the individuals’ environmental concerns in the context of an ecotourism trip. Answers were collected using a 5-point anchored semantic scale where 1 means low importance, and 5 means high importance.

Table 2 shows the description of the items included in the analysis as well as their justification after a literature review about nature-based ecotourism products.

There is no agreement in the literature regarding the sustainability of ecotourism activities. While Ruhanen et al. (2015) argue that ecotourism and sustainable tourism are equivalent concepts, some authors contend that ecotourism is not always sustainable (Wall, 1997). Weaver and Lawton (2007) suggest that ecotourism attractions should be nature-based and focused on learning and education, with product management pursuing ecological, socio-cultural and economic sustainability.

In order to gain insight into the underlying latent structure regarding the individuals’ concern for the environment, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to determine the existence of latent factors that explain the variability of the scores obtained in the indicators used as a measurement instrument. These latent factors will be integrated a posteriori into the structure of the hybrid choice model.

Results of the EFA are presented in Table A.1 in the Annex. Three latent factors are identified, namely, community support (CS), nature interaction (NI) and nature connection (NC) using the Varimax rotation method. The results obtained for Barlett’s sphericity test (Barlet, 1937) suggest the existence of correlations between the indicators that allow the dimension to be reduced. In addition, the Kaiser-Olkin-Meyer test (Kaiser, 1970) was 0.828, confirming the adequacy of the sample to perform an EFA.

Community support tourism is also known as Community-based tourism (CBT) (Lee & Jan, 2019), which is mainly defined as the ability to improve the quality of life of the local residents (Dodds et al., 2018). Developing such products improves the number of facilities, roads, parks, and other types of infrastructure, benefitting the residents’ quality of life without disrupting the local culture (Brunt & Courtney, 1999).

Environmental attitudes also interact with nature-based tourist products, and the activities developed in natural settings have also been influenced by tourists’ preferences. Nevertheless, the challenges imposed by nature-based tourist developments regarding environmental preservation have been controversial in the tourist literature (McCool, 2009). Lee and Jan (2015) contended that nature-based tourism is mainly based on the recreational feelings tourists experience from their contact with natural settings. For example, when tourists observe wildlife, they establish a close connection with them and consider protecting their environment and habitat important.

Nature connection is related to what other authors have denominated as a biospheric value representing personal moral norms about responsible behaviour towards the environment, nature or non-human objects (De Groot & Steg, 2008). Thus, a biospheric attitude uniquely explains a more pro-environmental behaviour associated with green consumption in the whole value chain that agglutinates the tourist experience (Han, 2015). Van der Werff et al. (2013) showed that tourists with a higher biospheric value are more personally connected to nature and the environment. For that reason, they are more naturally inclined towards protecting nature, ecosystems and the environment.

3.2. The Hybrid Choice Model

Based on the assumption that attitudes and perceptions play an important role in determining individuals’ choice behaviour, this paper estimates an integrated choice and latent variable model (ICLVM) to analyse how different latent constructs related to environmental concern influence preferences for sustainable tourism activities. After the seminal work of McFadden (1986) as well as posterior contributions of Ben-Akiva et al. (1999, 2002), ICLVM, also referred to in the literature as hybrid choice models (HCM), are currently considered the appropriate tool to incorporate the effect of latent variables into discrete choice models.

Latent variables (LVs), such as attitudes and perceptions, represent intangible attributes not directly observed by the researcher but may affect an individual’s decisions. These variables do not account for specific measurement scales, so they must be indirectly measured through indicators that manifest the underlying latent structure.

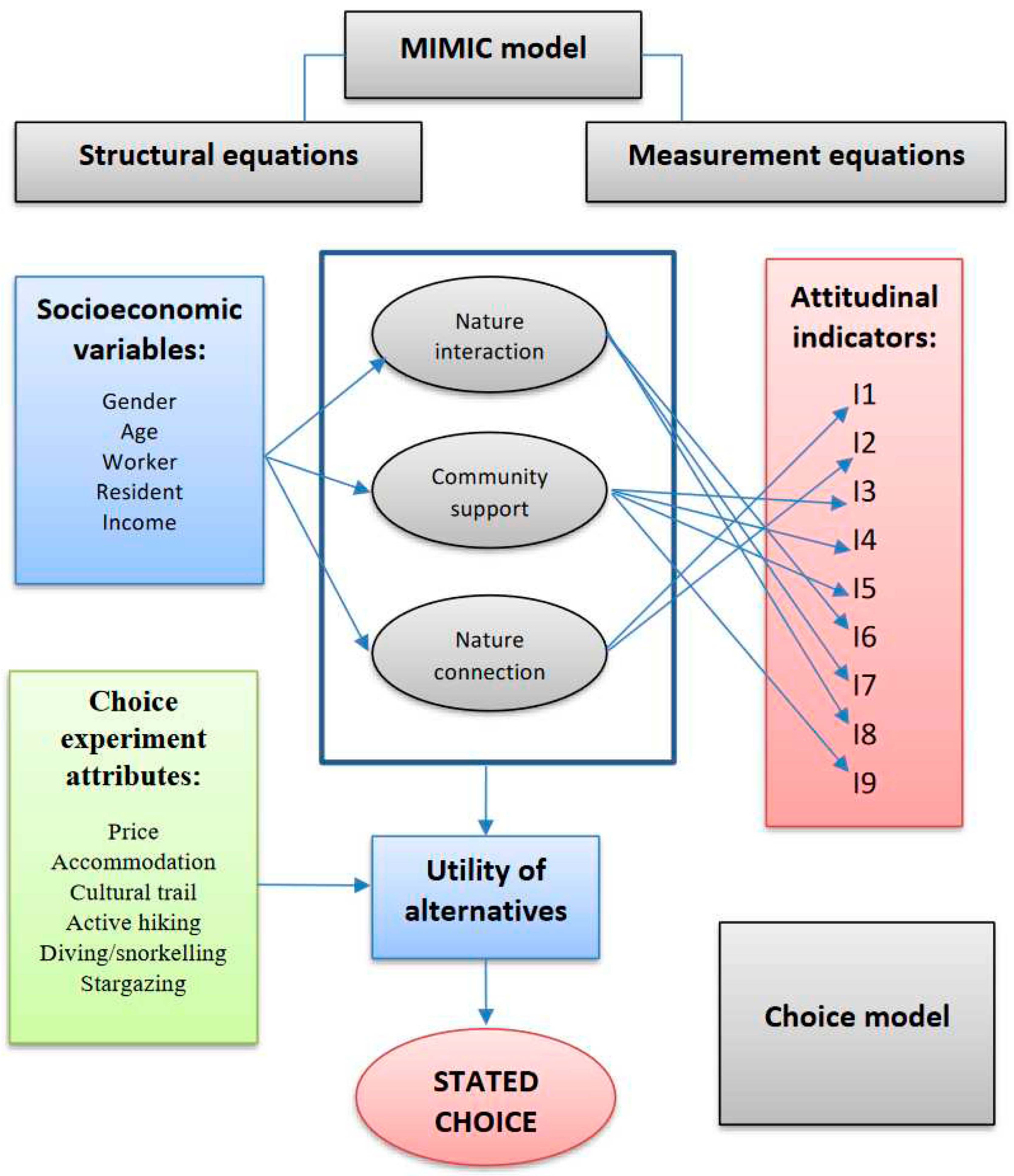

LVs are typically derived from a multiple indicator multiple causes (MIMIC) model, in which individuals’ socioeconomic characteristics explain these variables through structural equations. LVs, in turn, explain a collection of indicators through a set of measurement equations. LVs are then incorporated into the choice model as explanatory variables. In our case, LVs are specified by interacting with some of the attributes of the experiment. The parameters of the structural equation and the choice model are estimated simultaneously using the full information likelihood function.

The structure of the hybrid choice model is depicted in

Figure 1, and the specification of the equations of the different model components are as follows:

- 1)

The MIMIC model

-

a)

Structural equations

In the structural equations, the LVs are treated as random variables explained by a set of observed factors, such as socioeconomic data and a random term. In our model, the following structural equations for community support, nature interaction and nature connection are considered:

Where

GENDER is 1 for males,

AGE is one if the individual is older than 22 years,

WORK is 1 for active workers,

RESI is 1 for residents in Gran Canaria, and

INCOME represents the monthly income in thousands; the set of coefficients

and

are unknown parameters to estimate; and

is a random variable following the Standard Normal distribution.

For the sake of simplicity, the structural equations can be rewritten as:

Where

,

and

represent the mean of the latent random variables.

-

b)

Measurement equations

As stated above, LVs are indirectly measured by a set of indicators. Thus, measurement equations represent the relationship between the LV and the measurement instrument. Considering the latent structure obtained in the previous EFA, the measurement equations represent the indicators as random variables through the following expressions:

Where

are random variables following the Standard Normal distribution and coefficients

and

are parameters to estimate. As not all the parameters are identifiable, the intercept coefficients

,

and

are normalised to 0; the slope parameters

,

and

are normalised to 1; and the standard deviations

,

and

are normalised to 1.

Depending on the nature of the indicators, they can be treated as continuous or discrete variables. In our case, we use a semantic ordered scale of importance as a measurement instrument. Therefore, indicators are represented by discrete ordered variables. Thus, each measurement equation represents a latent regression that can be modelled using an ordered Probit model, where each score is identified as pertaining to a category delimited by specific threshold values of the dependent variable. Four threshold values could be estimated for 5-point scales. However, the assumption of symmetry in the indicators could reduce the number of parameters to just two by considering and so that the thresholds are defined as , , and (see Greene & Hensher, 2010 for a comprehensive revision of ordered choice models).

- 2)

The choice model

The utility of the alternatives in the choice model is defined in terms of the attributes considered in the experiment and the LVs obtained from the MIMIC model. Incorporating these LVs variables into the choice model was in the form of interactions with the attributes of the alternatives. Different specifications were tested during the modelling process, and the one producing more consistent results was that considering the interactions of community support and the accommodation type and cultural trail; nature interaction and active hiking, diving/snorkelling and stargazing; and nature connection and the alternative specific constant of the non-choice option. Thus, the utility of the alternatives are specified as follows:

where

are parameters to be estimated, and the explanatory attributes are named as in

Table 1.

Assuming the error terms are iid Extreme Value Type I distributed, the choice probabilities for the multinomial Logit model can be derived (Train, 2009). It is worth noting that attribute coefficients are interpreted as marginal utilities; thus, calculating the ratio of these marginal utilities and the negative of the price coefficient, the willingness to pay figures (WTP) are obtained (McFadden, 1981).

There are different approaches to estimating the parameters of the hybrid choice model. Sequential estimation entails first estimating the MIMIC model and then including the latent variables into the specification of the choice model in a subsequent stage. Although this is a relatively straightforward strategy, it yields inefficient estimates. In this sense, Bierlaire (2018) suggests simultaneously estimating the parameters of the structural and choice models by considering the full information likelihood function obtained from indicators and choice data.

4. Results and Discussion

Estimation results are presented in

Table 3. Unknown parameters were estimated using the simulated maximum likelihood method with the software Pandas Biogeme (Bierlaire, 2018). All the measurement model parameters were significant and estimated with the appropriate sign. All the slope parameters were positive, consistent with the measurement instrument used for the latent factors. Thus, a higher value of the corresponding LV would be compatible with a higher score obtained for the indicator. In this sense, we highlight that all the items included in the measurement model were positive; that is, a higher value of the indicator means a higher environmental concern.

Table 3.

Estimation results.

Table 3.

Estimation results.

| Parameter and variable names |

Estimated coefficient |

Std. err. |

t-test |

p-value |

| Choice model parameters |

|

ASC3 x Nature connection |

1.250 |

0.180 |

6.93 |

0.000 |

|

ASC3 |

-3.180 |

0.298 |

-10.70 |

0.000 |

|

Accommodation x Community support |

0.133 |

0.060 |

2.21 |

0.027 |

|

Accommodation |

0.394 |

0.063 |

6.25 |

0.000 |

|

Active Hiking x Nature interaction |

0.662 |

0.085 |

7.76 |

0.000 |

|

Active Hiking |

0.076 |

0.131 |

0.58 |

0.561 |

|

Cultural trail x Community support |

0.815 |

0.096 |

8.46 |

0.000 |

|

Cultural trail |

-0.015 |

0.103 |

-0.14 |

0.886 |

|

Diving/snorkelling x Nature interaction |

0.521 |

0.075 |

6.97 |

0.000 |

|

Diving/snorkelling |

0.767 |

0.115 |

6.64 |

0.000 |

|

Price |

-0.042 |

0.002 |

-20.60 |

0.000 |

|

Stargazing x Nature interaction |

0.504 |

0.090 |

5.61 |

0.000 |

|

Stargazing |

-0.214 |

0.142 |

-1.51 |

0.131 |

| Measurement model parameters |

| LV community support |

|

Intercept I4

|

-0.209 |

0.028 |

-7.36 |

0.000 |

|

Intercept I5

|

0.134 |

0.028 |

4.80 |

0.000 |

|

Intercept I9

|

0.175 |

0.028 |

6.16 |

0.000 |

|

Slope I4

|

1.100 |

0.028 |

40.10 |

0.000 |

|

Slope I5

|

1.010 |

0.028 |

36.40 |

0.000 |

|

Slope I9

|

1.040 |

0.029 |

36.40 |

0.000 |

|

Standard deviation I4

|

0.941 |

0.015 |

63.60 |

0.000 |

|

Standard deviation I5

|

0.963 |

0.015 |

63.20 |

0.000 |

|

Standard deviation I9

|

0.949 |

0.016 |

61.40 |

0.000 |

| LV Nature interaction |

|

Intercept I7

|

-1.320 |

0.052 |

-25.20 |

0.000 |

|

Intercept I8

|

-1.290 |

0.046 |

-27.90 |

0.000 |

|

Slope I7

|

1.210 |

0.034 |

35.20 |

0.000 |

|

Slope I8

|

1.190 |

0.030 |

39.90 |

0.000 |

|

Standard deviation I7

|

1.200 |

0.019 |

63.40 |

0.000 |

|

Standard deviation I8

|

0.990 |

0.016 |

61.90 |

0.000 |

| LV Nature connection |

|

Intercept I2

|

0.488 |

0.048 |

10.10 |

0.000 |

|

Slope I2

|

1.440 |

0.041 |

35.00 |

0.000 |

|

Standard deviation I2

|

1.100 |

0.023 |

47.00 |

0.000 |

|

Threshold parameter |

1.200 |

0.011 |

114.00 |

0.000 |

|

Threshold parameter |

0.702 |

0.013 |

52.80 |

0.000 |

Table 3.

Estimation results (cont).

Table 3.

Estimation results (cont).

| Structural model parameters |

|---|

|

Intercept community support |

0.915 |

0.038 |

24.30 |

0.000 |

|

Intercept nature interaction |

1.640 |

0.040 |

41.00 |

0.000 |

|

Intercept nature connection |

1.590 |

0.044 |

36.60 |

0.000 |

|

Gender in community support |

-0.238 |

0.024 |

-10.10 |

0.000 |

|

Gender in nature interaction |

-0.184 |

0.025 |

-7.47 |

0.000 |

|

Gender in nature connection |

-0.178 |

0.027 |

-6.56 |

0.000 |

|

Age in community support |

-0.053 |

0.024 |

-2.16 |

0.031 |

|

Age in nature interaction |

-0.138 |

0.026 |

-5.39 |

0.000 |

|

Age in nature connection |

-0.064 |

0.028 |

-2.27 |

0.023 |

|

Work in community support |

-0.087 |

0.030 |

-2.93 |

0.003 |

|

Work in nature interaction |

-0.066 |

0.031 |

-2.14 |

0.032 |

|

Work in nature connection |

0.037 |

0.034 |

1.08 |

0.280 |

|

Resi in community support |

0.071 |

0.031 |

2.29 |

0.022 |

|

Resi in nature interaction |

-0.134 |

0.033 |

-4.11 |

0.000 |

|

Resi in nature connection |

-0.432 |

0.037 |

-11.70 |

0.000 |

|

Income in community support |

-0.027 |

0.032 |

-0.84 |

0.399 |

|

Income in nature interaction |

0.037 |

0.034 |

1.10 |

0.273 |

|

Income in nature connection |

-0.212 |

0.037 |

-5.73 |

0.000 |

|

Standard deviation structural model |

0.702 |

0.013 |

52.80 |

0.000 |

|

Initial log-likelihood: |

-121639.9 |

|

|

|

|

Final log-likelihood: |

-67644.8 |

|

|

|

|

Rho-square |

0.444 |

|

|

|

| N |

Number of observations |

5712 |

|

|

|

In the structural model, all parameters resulted significant at the 95% confidence level, with the only exceptions of income in community support and nature interaction and work in nature connection. Regarding the impact of socioeconomic characteristics on the different LVs, females, local residents, those not currently working, and those younger than 22 have higher community support attitudes. Females, non-local residents, those not currently working, and those younger than 22 have higher nature interaction attitudes. Finally, females, non-local residents, younger than 22 and those with lower income present higher nature connection attitudes. In addition, the intercept parameters were all positive, indicating that other unknown factors positively impacted the three LVs’ attitudes towards the environment.

In the choice model, our results support the hypothesis that attitudes related to environmental concerns affect choice behaviour. In this case, most of the parameters resulted significant at the 95% confidence level, except the reference coefficients for active hiking (), cultural trail () and stargazing (). These results indicate that including these activities in the package is preferred by those with positive and non-negligible attitudes towards nature interaction and community support. In contrast, the accommodation in a rural house and diving/snorkelling activity would be more preferred even for individuals for whom these attitudes were represented by figures close to zero.

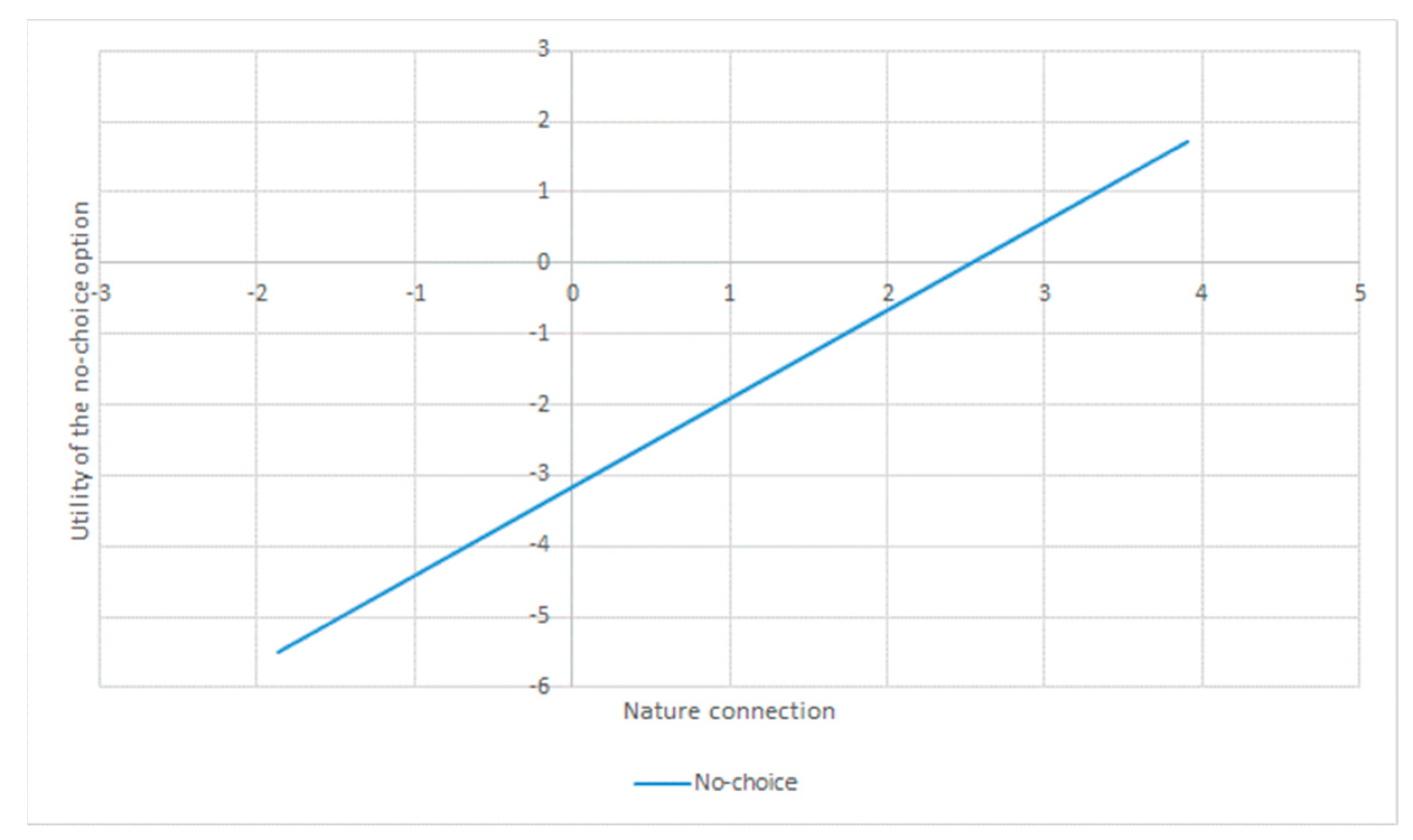

It is important to stress that negative attitudes may lead to a negative preference —i.e. a negative marginal utility— for the attribute in question. In our model, the majority of individuals presented positive attitudes towards community support (84.87%), nature interaction (97.18%) and nature connection (94.45%). Our findings show that individuals with higher community support attitudes exhibit higher preferences for rural house accommodation and cultural trail activities. In addition, individuals with higher nature interaction attitudes have a stronger preference for active hiking, diving/snorkelling, and stargazing activities. On the contrary, individuals with a higher attitude related to nature connection show a lower preference for active tourism packages; in other words, a higher preference for the no-choice option.

Figure 2 depicts the preference for the no-choice option regarding nature connection. The graphic shows that, for most individuals, the constant term of the no-choice alternative is negative, suggesting the existence of unobservable factors that indicate a clear preference for alternatives offering sustainable tourism packages when the effect of the characteristics of the package itself is considered negligible.

On average, Dive/snorkelling activities have the highest WTP (35.40€), followed by active hiking (23.53€). On the other hand, cultural trail and star gazing are the least valued activities, with 13.87€ and 11.43€, respectively. It is also worth pointing out that individuals are willing to pay 11.72€ to stay in a rural house rather than a tent.

In monetary terms, the willingness to pay for improving an attribute (𝑋

𝑖) of alternative i represents the increases in the utility of the alternative

produced by this improvement. They can be obtained from the choice model parameters using the following expression (Train, 2009).

Where the partial derivatives are replaced by increments for discrete attributes.

In our model, the numerator in the former expression varies across individuals as the explanatory attributes representing the activities considered in the package and the type of accommodation interact with some of the LVs considered in the analysis.

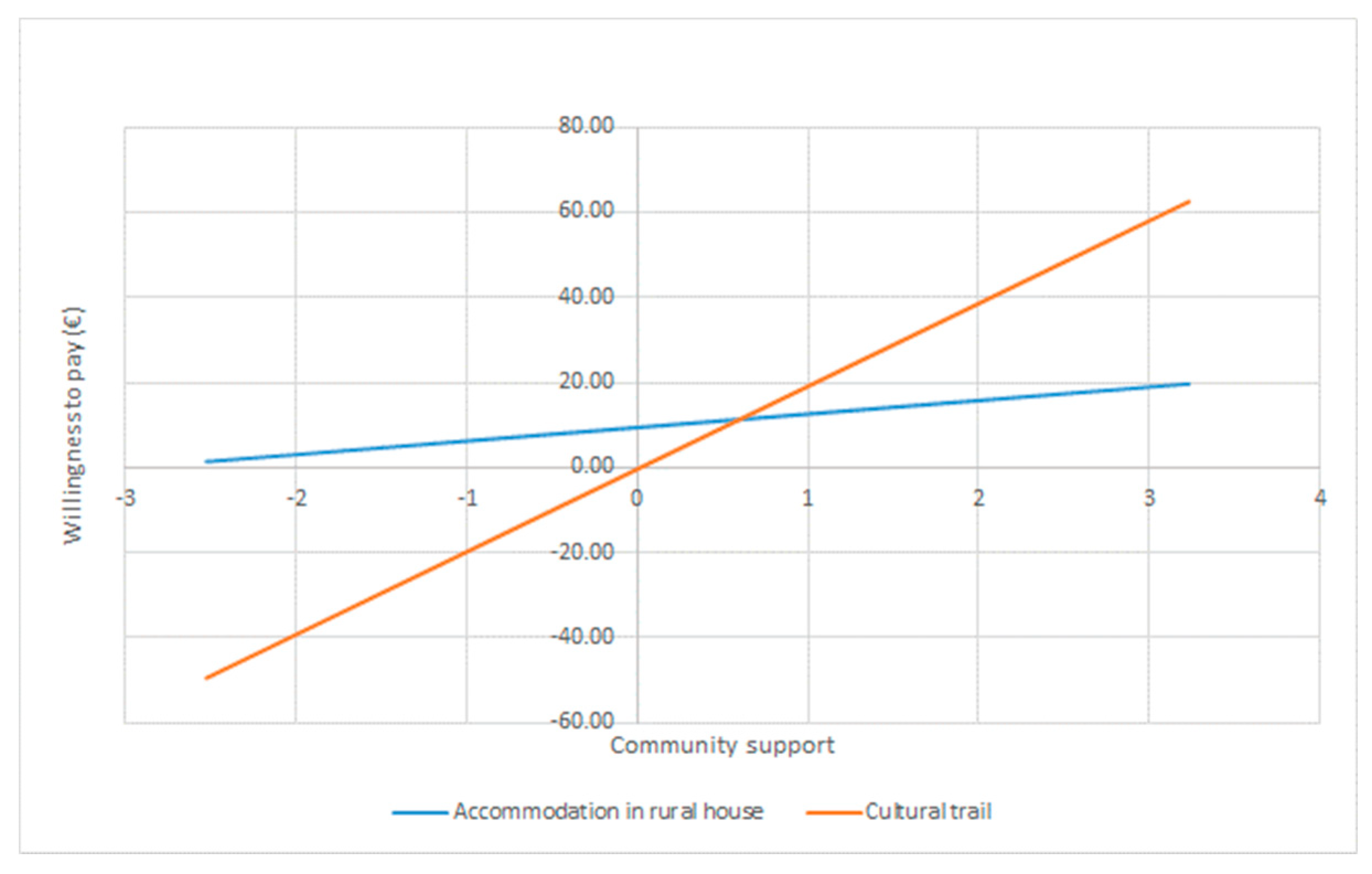

Figure 3 shows the WTP for the accommodation in a rural house and cultural trail activity regarding the LV community support. It is important to note that the WTP for cultural trail yields a negative figure (15.8%) for some individuals, indicating that they perceive a negative utility when this activity is included in the package. The result will have important managerial implications suggesting incorporating compensation mechanisms when designing the tourism packages to meet this market segment’s needs.

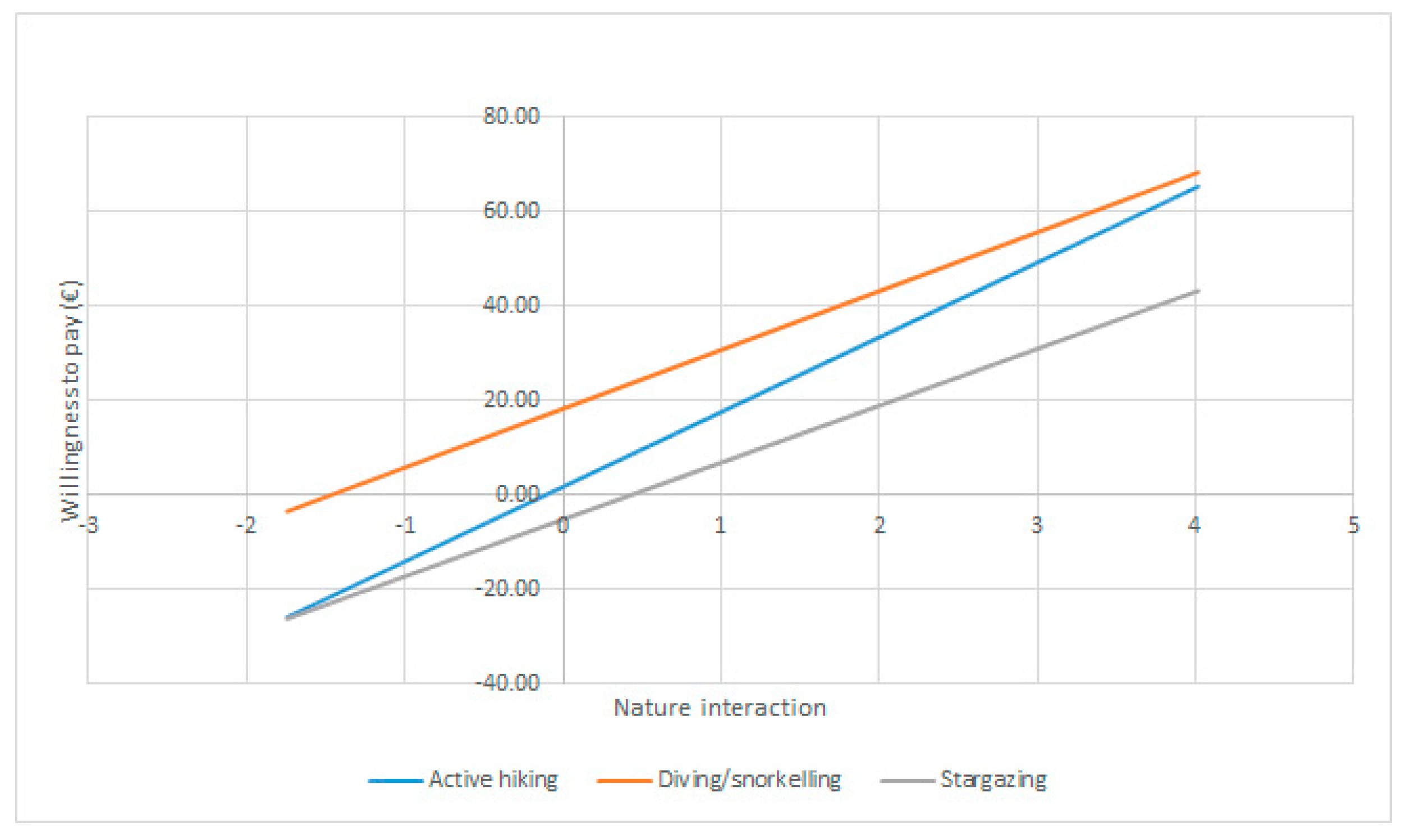

The WTP figure in terms of the LV nature interaction is depicted in

Figure 4. The graphic shows that for all the individuals in the sample, diving/snorkelling is the most valued activity, followed by active hiking and stargazing. In this case, the proportion of individuals with negative WTP is substantially lower: 1.9% for active hiking, 0.02% for diving/snorkelling and 8.9% for stargazing.

Table 4 presents the average WTP figures for the whole sample and the socioeconomic groups studied. Thus, on average, diving/snorkelling activities have the highest WTP (35.40€), followed by active hiking (23.53€). On the other hand, cultural trail and star gazing are the least valued, with 13.87€ and 11.43€, respectively. It is also worth pointing out that individuals are willing to pay 11.72€ to stay in a rural house rather than a tent. In general, females and those under 22 exhibit higher WTP figures for all the attributes. Similar figures are obtained for active and non-active workers, except in the case of the cultural trail, where non-active workers are willing to pay 2.7 euros more. Residents in Gran Canaria are willing to pay more for being accommodated in a rural house and for having cultural trails in the packages. In contrast, non-residents value active hiking trails, diving/snorkelling and stargazing activities more. These results are consistent with the parameter estimates obtained in the structural model and highlight the importance of incorporating latent variables into the choice model.

Table 4.

WTP figures (average/socioeconomic group).

Table 4.

WTP figures (average/socioeconomic group).

| Socioeconomic Group |

Willingness to pay (€) |

| Accommodation in a rural house |

Cultural trail |

Active hiking |

Diving / Snorkelling |

Stargazing |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

12.11 |

16.21 |

25.29 |

36.79 |

12.77 |

| Male |

11.35 |

11.59 |

21.81 |

34.04 |

10.12 |

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

| Younger than 22 years |

11.99 |

15.51 |

25.16 |

36.68 |

12.67 |

| Older than 22 years |

11.51 |

12.58 |

22.24 |

34.38 |

10.44 |

|

Activeworker

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

11.96 |

15.33 |

23.50 |

35.37 |

11.40 |

| Yes |

11.52 |

12.60 |

23.56 |

35.42 |

11.45 |

|

Residentin Gran Canaria

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No |

11.50 |

12.50 |

24.26 |

35.97 |

11.98 |

| Yes |

11.95 |

15.24 |

22.80 |

34.82 |

10.87 |

| Total |

11.72 |

13.87 |

23.53 |

35.40 |

11.43 |

Our findings have important managerial implications, providing interesting information for those designing nature-based tourism products. In this regard, knowing the amount different market segments are willing to pay for a particular activity is paramount in creating successful product packages that consider the normally hidden tourists’ preferences. This is especially relevant in the context of a mass tourism destination where young consumers could help in moving towards more sustainable tourism activities.

5. Conclusions

This research addresses the role of sustainable tourism activities in Gran Canaria, which constitutes an exciting niche market on an island traditionally dominated by 3S hotel tourism. Like other tourist destinations, Gran Canaria must face the challenge of revitalising tourism activity following the collapse caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. In this sense, promoting nature-based tourism products represents a challenge to achieve more sustainable tourism development.

The analysis results provide significant information about preferences and willingness to pay for diverse activities included in a typical active tourism package. In summary, it has been found that a majority of individuals prefer vacation packages that include sleeping in rural houses or tents, active hiking routes, including visits to natural spots such as natural pools, and dive or snorkel activities. Despite an a priori homogeneous sample composition of study participants, our findings reveal a significant heterogeneity in preferences and willingness to pay for the various activities under consideration when attitudinal latent factors related to environmental concern are incorporated into the model. Our results reinforce the methodology’s potential for extracting valuable information from study participants while providing interesting managerial recipes that tourism entrepreneurs can use to promote active tourism products as an alternative to the less sustainable 3S mass tourism.

Our findings represent a first step towards understanding the demand for sustainable tourism products in a natural setting, and they pave the way for future research. Other objectives for future research could include determining preferences for other water and mountain-related activities for tourism product development in other areas of the Canary Islands archipelago. It might also be interesting to look into preferences for other potential customer groups, such as other age ranges and nationalities. Other attitudinal factors, such as the mitigation measures taken by tourists and climate change awareness, could also be worth investigating.

Annex

Table A.1.

Exploratory factor analysis results.

Table A.1.

Exploratory factor analysis results.

| Indicator |

Description |

Factor Loadings* |

| Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

| I1 |

The connection of the human being with nature |

|

|

0.698 |

| I2 |

The preservation of nature |

|

|

0.549 |

| I3 |

Know and share the customs and traditions of the peoples |

|

0.432 |

|

| I4 |

That agricultural and livestock activities be carried out in a traditional way and with low impact |

|

0.556 |

|

| I5 |

To promote the economic development of communities where ecotourism activities are carried out |

|

0.645 |

|

| I6 |

Enjoy the grandeur of the mountains and its landscape when walking on natural trails. |

0.420 |

|

|

| I7 |

Observe birds and other species in their natural habitat. |

0.813 |

|

|

| I8 |

Getting to know the native flora |

0.619 |

|

|

| I9 |

Recovering trails and routes for ecotourism purposes |

|

0.416 |

|

| |

Factor labelling |

Nature interaction |

Community support |

Nature

connection |

| |

SS Loading |

1.507 |

1.326 |

1.240 |

| |

Explained Variance |

16.7% |

14.7% |

13.8% |

| |

Cumulative explained variance |

16.7% |

31.4% |

45.2% |

| *Loadings below a threshold of 0.4 have been omitted |

References

- Albaladejo, I. P. , & Díaz-Delfa, M. T. The effects of motivations to go to the country on rural accommodation choice: A hybrid discrete choice model. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1484–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Baral, N. , Stern, M. J., & Hammett, A. L. Developing a scale for evaluating ecotourism by visitors: A study in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 975–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M. S. The statistical conception of mental factors. Br. J. Psychol. 1937, 28, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, C. T. , McLeod, D. M., Germino, M. J., Reiners, W. A., & Blasko, B. J. Environmental amenities and agricultural land values: A hedonic model using geographic information systems data. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 40, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Akiva, M. , McFadden, D., Gärling, T., Gopinath, D., Walker, J., Bolduc, D., Börsch-Supan, A., Delquié, P., Larichev, O., Morikawa, T., Polydoropoulou, A., Rao, V. Extended Framework for Modeling Choice Behavior. Mark. Lett. 1999, 10, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Akiva, M. , McFadden, D., Train, K., Walker, J., Bhat, C., Bierlaire, M., Bolduc, D., Boersch-Supan, A., Brownstone, D., Bunch, D.S., Daly, A., de Palma, A., Gopinath, D., Karlstrom, A., Munizaga, M. A. Hybrid Choice Models: Progress and Challenges Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Mark. Lett. 2002, 13, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bierlaire, M. Estimating choice models with latent variables with PandasBiogeme. Rep. TRANSP-OR 2018, 181227.

- Bimonte, S. , & Faralla, V. Happiness and nature-based vacations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliemer, M. C. , & Rose, J. M. Construction of experimental designs for mixed logit models allowing for correlation across choice observations. Transp. Res. Part B: Methodol. 2010, 44, 720–734. [Google Scholar]

- Börjes, I. Gran Canaria, 4. Aktualisierte und überarbeitete Auflage 2008, Michael Müller Verlag Gmbh, Erlangen.

- Brunt, P. , & Courtney, P. Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budeanu, A. Sustainable tourist behaviour–a discussion of opportunities for change. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C. N. , Kalavar, J. M., & Melubo, K. Tourism and community well-being: The case of the Maasai in Tanzania. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 44, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Soria, J. A. , Núñez-Carrasco, J. A., & García-Pozo, A. Environmental concern and destination choices of tourists: Exploring the underpinnings of country heterogeneity. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 532–545. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. Y. , & Jim, C. Y. Contingent valuation of ecotourism development in country parks in the urban shadow. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChoiceMetrics (2009). Ngene 1.0. User manual & reference guide. The Cutting Edge in Experimental Design. Retrieved from www.choice-metrics.com.

- Cordente-Rodríguez, M., Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. A., & Villanueva-Álvaro, J. J. Sustainability of nature: The power of the type of visitors. Environmental Engineering & Management Journal (EEMJ) 2014, 13.

- Curtin, S. Wildlife tourism: the intangible, psychological benefits of human–wildlife encounters. Curr. Issues Tour. 2009, 12, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J. I. M. , & Steg, L. Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Knop, P. Sport for all and active tourism. World Leis. Recreat. 1990, 32, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R. , Ali, A., & Galaski, K. Mobilizing knowledge: determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, F. , Pintassilgo, P., & Pinto, P. Environmental awareness of surf tourists: A case study in the Algarve. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 3, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, J. E. , & Nuli, S. Millennials’ environmental awareness, price sensitivity and willingness to pay for Green Hotels. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2018, 10, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Giddy, J. K. , & Webb, N. L. Environmental attitudes and adventure tourism motivations. GeoJournal 2018, 83, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. H., & Hensher, D. A. (2010). Modeling ordered choices: A primer. Cambridge University Press.

- Han, H. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, A. R. , & Kolstad, J. R. Mixed logit estimation of willingness to pay distributions: a comparison of models in preference and WTP space using data from a health-related choice experiment. Empir. Econ. 2012, 42, 445–469. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, M. (1999). Ecotourism and Sustainable Development: Who Owns Paradise? Island Press, Washington, DC.

- Kaiser, H.F. (1970). A second generation little juffy. A second generation little juffy. Psychometrika 35 1999, 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Karampela, S. , Andreopoulos, A., & Koutsouris, A. “Agro”, “Agri”, or “Rural”: The Different Viewpoints of Tourism Research Combined with Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Lawson, R. W. , Williams, J., Young, T., & Cossens, J. A comparison of residents’ attitudes towards tourism in 10 New Zealand destinations. Tour. Manag. 1998, 19, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. H. , & Jan, F. H. The Effects of Recreation Experience, Environmental Attitude, and Biospheric Value on the Environmentally Responsible Behavior of Nature-Based Tourists. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T. H. , & Jan, F. H. Development and validation of the ecotourism behavior scale. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. H. , & Jan, F. H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltese, I. , & Zamparini, L. Sustainable mobility choices at home and within destinations: A survey of young Italian tourists. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023, 48, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, L. , & Hrankai, R. Modeling tourist accessibility to peripheral attractions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 92, 103343. [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, A. , & Rose, J. Balancing tourism, conservation, and development: a political ecology of ecotourism on the Galapagos Islands. J. Ecotourism 2016, 15, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S. F. Constructing partnerships for protected area tourism planning in an era of change and messiness. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. (1981). Econometric models of probabilistic choice. In: Manski, C., McFadden, D. (Eds.), Structural analysis of discrete data with econometric applications. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 198-272.

- McFadden, D., 1986. The Choice Theory Approach to Market Research. Marketing science, 5, 275–297.

- Neger, C. , & Propin Frejomil, E. Regional Ecotourism Networks: Experiences and Lessons from Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. Ann. Austrian Geogr. Soc. 2018, 160, 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacki, M. , Chawla, Y., & Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. What drives the eco-friendly tourist destination choice? The Indian perspective. Energies 2021, 14, 6237. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacki, M. , Kowalczyk-Anioł, J., & Chawla, Y. Gen Z’s Attitude towards Green Image Destinations, Green Tourism and Behavioural Intention Regarding Green Holiday Destination Choice: A Study in Poland and India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7860. [Google Scholar]

- Passafaro, P. Attitudes and tourists’ sustainable behavior: An overview of the literature and discussion of some theoretical and methodological issues. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passafaro, P. , Cini, F., Boi, L., D’Angelo, M., Heering, M. S., Luchetti, L.,... & Triolo, M. The “sustainable tourist”: Values, attitudes, and personality traits. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 15, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen, J. A. Targeting rural tourists in the internet: Comparing travel motivation and activity-based segments. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, M., & Gomes, S. (2023). Generation Z as a critical question mark for sustainable tourism–An exploratory study in Portugal. Journal of Tourism Futures. Forthcomming.

- Prazeres, L. , & Donohoe, H. The Visitor Sensescape in Kluane National Park and Reserve, Canada. J. Unconv. Parks Tour. Recreat. Res. 2014, 5, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Puciato, D. , Szromek, A. R., & Bugdol, M. Willingness to pay for sustainable hotel services as an aspect of proenvironmental behavior of hotel guests. Econ. Sociol. 2023, 16, 106–122. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido-Fernández, J. I. , & López-Sánchez, Y. Are tourists really willing to pay more for sustainable destinations? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1240. [Google Scholar]

- Root-Bernstein, M. , Rosas, N. A., Osman, L. P., & Ladle, R. J. Design solutions to coastal human-wildlife conflicts. J. Coast. Conserv. 2012, 16, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L. , Weiler, B., Moyle, B. D., & McLennan, C. L. J. Trends and patterns in sustainable tourism research: A 25-year bibliometric analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 517–535. [Google Scholar]

- Santarém, F. , Silva, R., & Santos, P. Assessing ecotourism potential of hiking trails: A framework to incorporate ecological and cultural features and seasonality. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H., Wu, H., & Zhang, H. (2023). Can nudging affect tourists’ low-carbon footprint travel choices? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. Forthcoming.

- Sultana, N. , Amin, S., & Islam, A. Influence of perceived environmental knowledge and environmental concern on customers’ green hotel visit intention: mediating role of green trust. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 14, 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Train, K. E. (2009). Discrete choice methods with simulation. Cambridge University Press.

- UNWTO. (2020). UNWTO World Tourism Barometer and Statistical Annex, January 2020 18.

- Van der Werff, E. , Steg, L., & Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V. K. , & Chandra, B. Sustainability and customers’ hotel choice behaviour: a choice-based conjoint analysis approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Wahnschafft, R. , & Wolter, F. Assessing tourist willingness to pay for excursions on environmentally benign tourist boats: A case study and trend analysis from Berlin, Germany. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023, 48, 100826. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, G. Is ecotourism sustainable? Environ. Manag. 1997, 21, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, D. B. , & Lawton, L. J. Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F. , & Fox, D. Modelling attitudes to nature, tourism and sustainable development in national parks: A survey of visitors in China and the UK. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W. , & Xue, X. The differences in ecotourism between China and the West. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).