1. Introduction

Much literature has been published on the connections between schools, museums, and science education. As an example, diverse studies since the 1990s [e.g., 1–7] emphasized the role of science museums as informal learning environments to enhance scientific literacy, a topic that is still discussed in recent studies [e.g., 8–21].

However, there is little available literature on school museums (in general) and science education (in particular). In her pioneering work, Smith [

22] defined a school museum as a collection of objects providing an element of wonder, usually used in hands-on activities to facilitate a child’s understanding of the realities of life. According to the author [

22], school museums thus represented valuable tools in teaching science for generating scientific interest and stimulating the learning processes. It is then worth mentioning that Smith [

22] stressed the importance of the correct materials’ care, preservation, and interpretation (e.g., supplying the objects with labels).

Regarding their origin, historians [e.g., 23–25] dated the first school museums –except for a few ones established in the pedagogic context of the experimental learning promoted by Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746–1820) [e.g., 26]– as an international phenomenon emerging in the second half of the 19th century during the temporary exhibitions on education and upbringing during the world’s fairs. Usually housed in primary and secondary schools, these museums displayed teaching materials and collections on local history and natural sciences. Usually housed in primary and secondary schools, these museums displayed teaching materials and collections on local history and natural sciences. In this regard, it is interesting to note that natural specimens, as highlighted by Newman & Driver [

25] (pp. 1223–1124), were supplied not only by teachers and parents but also by collectors, traders, municipal authorities, and missionaries. Moreover, the management of natural science collections was characterized by curation practices, including a rational mode of acquiring and displaying the specimens (e.g., unambiguous labeling, avoidance of duplicates, visual clarity, and accessibility) and by strategies to prevent damages due to agents of deterioration and careless handling [

27,

28]. Despite their increasing significance as valuable resources for object-based teaching and learning – to the point that they became travel destinations in educational tours [e.g., 29] – the shortage of classroom space and the lack of human and economic resources, together with the increasing importance of school visits to scientific exhibitions, lead school museums, as stated by Newman & Driver [

25] (p. 1230), to progressive disuse since the 20th century.

The factors mentioned above can also be listed between the causes of today's non-recovery and valorization of school collections. This results in the inevitable and progressive loss of a unique scientific, educational, and historical heritage that can occasionally be saved if it is merged into collections belonging to natural history museums –e.g., the teaching mineralogical collections of the Florentine Istituto Superiore di Magistero (comprising more than 465 specimens) acquired by the Natural History Museum of Firenze in the 1930s [

30] (p. 22)– or to educational museums such as the National Pedagogical Museum in Madrid [e.g., 31].

Regarding the Italian scenario, which represents the geographical and cultural background of this work, it is interesting to note that contemporary historiography, as stated by D’Ascenzo [

32,

33], considers the Italian school museums developed since the 19th century [e.g., 34–36] as a historical-educational heritage – also called school heritage [

37] – comprising not only teaching collections but also libraries and archives [e.g., 38–40], which is still in need to be correctly preserved and made known to students and teachers. To achieve this goal, Meda and D'Ascenzo [41, 33] underlined the establishment of educational museums, mostly based on academic institutions [

42], entirely devoted to preserving and displaying the school heritage such as the Museo della Scuola e dell'Educazione “Mauro Laeng” in Rome [e.g., 43], the Museo dell’Educazione in Padua [e.g., 44], the Museo della Scuola e del Libro per l'Infanzia in Turin [e.g., 45], the Museo Didattico e della Didattica in Piacenza [e.g., 46], the Museo della Scuola “Paolo e Ornella Ricca” in Macerata [e.g., 47–48] , and the Museo della scuola e dell'educazione popolare in Campobasso [e.g., 49]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy the establishment of the Italian Society for the Study of the Historical-Educational Heritage (Società Italiana per lo Studio del Patrimonio Storico-Educativo, SIPSE) in 2017, aiming to recover, safeguard, and make accessible to scholars and the general public the school heritage kept in local museums, centers for documentations, and educational institutions [e.g., 50–51]

Regarding the scientific school teaching collections [

52], diverse projects have focused on the recovery and valorization of instruments in disused school laboratories [e.g., 53–59]. The experiences are carried out within the National Plan for Scientific Degrees (Piano Nazionale per le Lauree Scientifiche, PNLS), i.e., a project established in 2014 by the Italian Minister of University and Research to enhance enrollment in science degree programs through work-based learning experiences performed in closed collaboration between teachers, secondary students, and academic researchers [e.g., 60]. PNLS is therefore strictly connected to the Third Mission of the universities (TM), which represents, as stated by Compagnucci & Spigarelli [

61] in their literature review, the progressive engagement of academic institutions in activities aiming to contribute to the social, economic, and cultural development of the geographical areas in which they are based, by transferring knowledge and technologies to industry and society. Furthermore, PNLS activities are part of the mandatory National Plan for Soft Skills and Guidance (Piano per le Competenze Trasversali e l’Orientamento, PCTO) [e.g., 62], previously known as School-Work Alternation (Alternanza Scuola-Lavoro, ASL). PCTO involves students (post-16 years old) enrolled in the last three years of the secondary education system for at least 90 hours of activities to help them make informed choices about their future university or work path. Even if the experiences mentioned above regarding the valorization of scientific teaching school collections focused on recovery of historical instruments, other projects involved natural history collections, which are primarily preserved in civic and university museums [e.g., 63–70]. However, PCTO experiences are insufficient to ensure a proper inventory, recovery, and valorization of the entire Italian educational heritage, especially when natural specimens are kept in private institutes and religious schools. In this regard, it must be noted that, despite the centuries-old tradition in science and education usually held by these institutions, their natural history collections –and the relative archival documentation– often remain unknown to scientists, pedagogists, museologists, and historians. This is the case of the 20

th-century zoological collection belonging to Barnabite Fathers in Naples that, as outlined in Adamo et al. [

71], has never been the subject of extensive studies and cataloging. Furthermore, no longer being used as teaching tools, these collections frequently lie in poor, conservative conditions.

The aim of this work is thus to highlight the importance of the correct preservation and valorization of natural history collections in religious schools by illustrating the recovery of the 18th-century geo-mineralogical collections belonging to the Collegio Nazareno of Rome, and now kept in the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio, a private institution run by the Piarist fathers that comprises classes from kindergarten to high school.

2. Materials and Methods

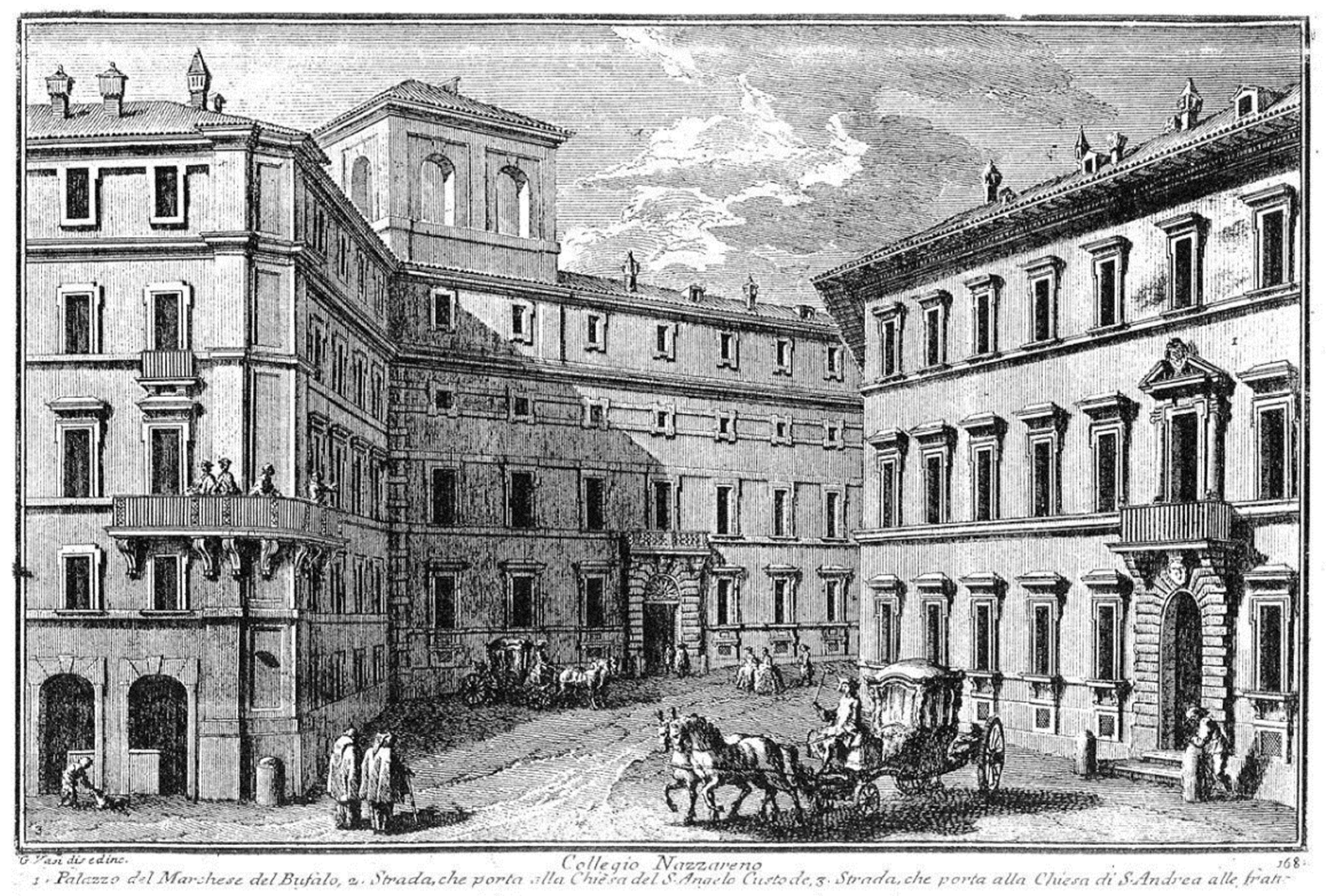

As mentioned in the Introduction Section, the geo-mineralogical collections kept at the Instituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio of Roma date back to the second half of the 18th century when they began to be assembled to establish the Mineralogical Cabinet within the Collegio Nazareno, one of the oldest Roman schools founded by Giuseppe Calasanzio (1557-1648) in 1630 [

72] (

Figure 1).

Collegio Nazareno thus represented a vibrant cultural center within the frame of Roman scientific academies since it was open to the influences of Jansenism and the Enlightenment [

73,

74] and characterized by teaching programs focused on enhancing scientific learning. Even if a comprehensive reconstruction of Collegio Nazareno’s history is out of scope here, it is interesting to note that Bartolomeo Gandolfi (1752-1824), later professor of experimental physics at La Sapienza University [

75], taught calculus and mathematical analysis, while Father Damaso Michetti (1732-1802) held regular anatomy lessons dissecting both animal and human corpses [

72] (pp. 122 and 141).

As stated by Maddaluno [

76] (p. 108), the Collegio Nazareno flourished in the 1780s under the rectorate of Father Giovanni Vincenzo Petrini (1725-1814), who founded the Mineralogical Cabinet, whose collections were enriched over the years by well-renewed naturalists –e.g., Scipione Breislak (1750-1826), Carlo Giuseppe Gismondi (1762-1824), and William Thomson (1761-1806); members of nobility –e.g., the Prince of Cerveteri, Francesco Maria Ruspoli (1752-1829) and the Elector of the Palatinate, Karl Theodor (1724-1799); popes and prelates –e.g., Pious VI (1711-1799) and the Cardinal Stefano Borgia (1731-1804). These donors, along with many others, were listed in the

Catalogo dei Benemeriti (Benefactors’ catalog), which was contained in Petrini’s

Gabinetto Mineralogico del Collegio Nazareno (Collegio Nazareno’s Mineralogical Cabinet), a two-volume treatise on mineralogy Petrini wrote between 1791 and 1792 starting from the description, analysis, and classification of Collegio Nazareno’s geo-mineralogical collections [

77] (pp. 23–28). This work was widely circulated that it ran out of stock [

78] (p. 298) and was praised for its scientific accuracy by figures such as the mineralogist and chemist Carlo Antonio Napione (1756-1814) [

79] (p. 470) and the collector Giacomo Filippo Durazzo (1729-1812). As stated in Raggio [

80] (p. 89), Durazzo used Petrini’s work as a model to arrange his private natural history cabinet. Collegio Nazareno’s Mineralogical Cabinet was thus renowned among 18th-century savants – e.g., Felice Fontana (1730-1805), who was the first director of the Imperial and Royal Natural History Museum in Firenze [

81], mentioned Collegio Nazareno’s collections in his epistolary [

82] (pp. 155-156)– and toured by diverse scholars such as the archeologist Pietro De Lama (1750-1825), who visited it between January and February 1791 [

83]. However, the Mineralogical Cabinet was firstly a research center and a teaching tool for Collegio Nazareno’s students. Here, mineralogical and chemical classes were held, and students practiced using the specimens in the collections. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the lectures given by Gismondi were open to the public since he believed that a private institution aimed to serve public education [

84]. The Mineralogical Cabinet prospered since the first half of the 20

th century thanks to the work of Piarist Fathers such as Adolfo Brattina (1852-1935), who held practical classes in mineralogical analysis, especially on silica minerals and quartz mineralogical associations with sulfides and sulfosalts [

85] (p. 19) using the specimens kept in the cabinet. This brief overview thus outlined how Collegio Nazareno’s geo-mineralogical collections were used in teaching and learning activities within a more extensive background of scientific and sociocultural practices [

86]. After the mid-1950s, the geo-mineralogical collections lost their role as a learning tool and were gradually disused, thus leading to a progressive decay of the specimens’ conservation state. In early 2012, the collections were transferred from the historical location of Palazzo Nazareno to the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio [

87].

After moving to the Istituto San Giuseppe Calsanzio, a small part of the surviving specimens was placed in wooden and glass cabinets in front of the Father Pusino school theater on the ground floor of the institute. At the same time, most were stored in plastic boxes, together with their original handcrafted wooden cassettes used to display them in the past, in the basement. The geo-mineralogical collections were thus neither used in teaching activities nor accessible to the general public. On the sides of the ancient wooden boxes, the presence of rectangular-shaped paper labels was noticed. The latter bore the printed wording “Gabinetto Collegio Nazareno” (Nazarene College’s Cabinet) and (when present) the handwritten inventory numbers, mineral species naming, its and provenance. Some boxes then reported the specimen’s inventory number and mineralogical classification on the wood surface. Others had no information at all (

Figure 2).

Both the labels and the wooden boxes showed various conservation conditions. In particular, the cassettes containing sulfides and their relative labels presented the most significant degree of alteration, resulting in the formation of sulfates.

The project of recovery, study, and valorization of the Collegio Nazareno’s geo-mineralogical collections, in which the fourth and fifth grades of the local Scientific and Foreign Language High Schools also participated, started with securing all specimens found in the area in front of the school theater and the basement. In this regard, the samples in the basement were at the greatest risk of damage, loss, and breakage because they were stored in unsealed plastic bags and thus exposed to agents of deterioration such as dust and pests.

All the recovered samples were photographed using a DSLR camera, a still-life table, LED lights, and a scale cube. UV lights were used to decipher labels on the specimens’ surface, usually reporting the inventory number, in poorly conservative conditions. The specimens were included in an offline electronic database comprising their weight and historical mineralogical identification as noted in the Mineralogical Cabinet’s inventory, drawn by the natural sciences professor Augusto Zanotelli in 1898, now kept in the Historical Archive of the Collegio Nazareno.

After completing the inventory process, a cataloging campaign using the national standards issued by the Istituto Centrale per il Catalogo e la Documentazione (Central Institute for Cataloging and Documentation, hereafter ICCD), which is part of the Ministero della Cultura (Italian Minister of Culture, MiC), was launched to study and valorize the specimens. The catalographic standards devoted to the catalog of Italian natural heritage consist of seven models regarding minerals (Beni Naturalistici – Mineralogia, BNM) [

88]; paleontological, botanic, and zoological specimens (Beni Naturalistici – Paleontologia, BNP, Beni Naturalistici – Botanica, BNB, Beni Naturalistici – Zoologia, BNZ) [

89,

90,

91]; human remains found in archeological contexts and anatomical preparations kept in morbid anatomy museums (Antropologia Fisica, AT) [

92]; meteorites (Beni Naturalistici – Planetologia, BNPL) and rocks (Beni Naturalistici – Petrologia, BNPE) [

93,

94]. Since the specimens recovered at the Instituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio comprised only minerals and rocks, the BNM and BNPE standards, described in Pratesi and Franza [

95], were used. The catalog datasheets were compiled on the online platform SIGECweb [

96], and the resulting records were published in Open Access (OA) on the General Catalog of Cultural Heritage (Catalogo Generale dei Beni Culturali, CGBN) database [

97].

With regards to the designer of a new and secure storage area, a storeroom equipped with stackable plastic containers for the long- and short-term storage of geo-mineralogical specimens was arranged in front of the Father Pusino school theater. The samples were placed in zippered plastic bags to avoid damage caused by agents of deterioration. Wooden boxes were also bagged and placed in separate containers, while detached labels were placed in acid-free paper for archival storage. Finally, a new permanent exhibition area was designed on the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio ground floor.

Once the cataloging campaign and the arrangement of the permanent collection in the new display were completed, a workshop for the science teachers was organized to illustrate the project's key findings and the possible learning activities to be performed using the recovered geo-mineralogical specimens and the catalog records. Finally, a round table was held for the fourth and fifth high school classes to discuss the importance of preserving natural history school collections and their cataloging according to ICCD national standards.

3. Results

The project concerning the recovery and study of the 18th-century geo-mineralogical collections belonging to the Collegio Nazareno in Rome and now housed at the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio retrieved 1724 specimens. Due to the poor storage conditions, diverse specimens (ca. 100 units) were treated with basic conservation remedies [

98], such as manually removing dust and decay products (

Figure 3).

Sixteen asbestiform minerals were double bagged in heavy plastic bags to minimize the health risks.

All the recovered specimens were inventoried in an offline database to be used by science and history teachers to program cross-curricular learning activities. Two hundred specimens were cataloged using the BNM and BNPE national standards on the SIGECweb platform, and the records were published in OA on the General Catalog of Cultural Heritage database.

The most striking result from the cataloging campaign was the recovery of 59 specimens belonging to the mineralogical collection donated to Collegio Nazareno’s Mineralogical Cabinet by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II (1765–1790) in 1785 (

Table 1).

The specimens illustrated in

Table 1 and the other 250 geo-mineralogical samples taken from the deposit were displayed in the new exhibit area, as shown in

Figure 4.

At the end of the project, a fourth-grade student included in his PCTO activities the cataloging of rock and mineral specimens kept in the storage area according to the ICCD national BNM and BNPE standards.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the importance of preserving and valorizing disused natural history collections in schools, particularly private and religious institutes. The project aimed to recover and make accessible to teachers, students, and the general public the 18th-century geo-mineralogical collections that belonged to the Mineralogical Cabinet of the Collegio Nazareno and are now kept at the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio of Roma.

It was found that 1724 geo-mineralogical specimens and relative archival documentation (i.e., paper labels attached on the specimens' surface and on the original display wooden boxes) were kept in poorly conservative conditions since the collections were no longer used as didactic and research tools from the second half of the 20th century. Regarding the paper labels, one interesting finding was that diverse typologies, usually showing inventory numbers and often overlapping, were found on most specimens. A comparative analysis between those on the top presenting a blue ornament and the documents preserved at the Historical Archive of the Collegio Nazareno revealed that the labels reported the inventory numbers included in Zanotelli’s 19th-century inventory.

Therefore, the offline database containing the inventory data of all the recovered specimens was updated with new information, such as the name of a specimen’s donor (if any). All this data (i.e., mineral species naming, samples’ provenance, donor’s name, weight, and conservation status) was unknown before this study and thus contributed to outlining a comprehensive scientific and cultural biography of the recovered specimens [

99].

Another finding that stands out from the results reported earlier is the discovery of 59 massive specimens comprising rocks and minerals given to Collegio Nazareno’s Mineralogical Cabinet by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II (

Table 1). This donation, as outlined in Mottana et al. [

100] and Mottana [

101], dated back to 1785 and was briefly described by Petrini in the preface to the first volume of his mineralogical treatise [

77] (p. 25). The specimens’ identification was made possible by the retrieval of paper labels showing, on their upper side, the printed Latin wording «Ex Munificentia Josephi. II. Rom. Imp. Aug.» and the double-headed eagle representing the House of Habsburg coat of arms (

Figure 5).

As outlined in Franza & Pratesi [

101], these specimens are the only ones that can be currently attributed with certainty to Joseph II since no other mineralogical samples – preserved, for example, at the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna, where the Habsburg natural history collections are kept– reported the same labeling or any other distinctive mark related to Joseph II. As illustrated in

Figure 5, the Habsburg labels showed the specimen’s mineralogical species, geographical provenance, and the sample’s inventory number as listed in the donation. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the mineralogical collection was to include at least 500 samples, as shown by the higher inventory number recovered. According to Petrini [

77] (p. 25), the labels were drawn by the naturalist Ignaz Edler von Born (1742-1791), who also ordered and cataloged the 18

th-century mineralogical collections belonging to the members of the Habsburg-Lorraine royal family [

102].

Concerning the cataloged specimens using the BNM and BNPE national standards belonging to Joseph’s II donation, what stands out is their exclusive provenance from today's Austria, Hungary, Slovakia, and Romania and the presence of rock samples from the Austrian territories. . As an example, Petrini [

77] (p. 68) underlined that the numerous «yellow pyrite» specimens coming from today’s abandoned mine of Smolnik (Slovakia) entered the Mineralogical Cabinet thanks to the «royal munificence of Joseph II».

As stated by Allen [

103], designing a scientific exhibition is a constructivist dilemma since the display is an effective teaching tool if it facilitates immediate apprehendability and visitors’ physical interactivity while showing a conceptual coherence granted by the results of a strong research program during its design processes. Therefore, all the data retrieved by the cataloging campaign guided the arrangement of the new exhibition on the ground floor of the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio. Before the renovation, the area in front of the school theater was used for the kindergarten canteen during the Covid-19 pandemic. The new exhibition includes ten high-specialized showcases to display the mineralogical specimens (

Figure 4). The first three exhibit the aesthetic minerals retrieved from the historical surviving samples. These display cases thus represent useful teaching tools for middle school students, who can learn, for example, about the phenomenon of color in minerals and its importance in identifying mineralogical specimens [

104]. The following four showcases are devoted to the exhibition of the surviving samples comprising the collection donated by Joseph II to the Mineralogical Cabinet of the Collegio Nazareno. The specimens are displayed together with new museum tags showing the historical mineralogical identification and relative inventory number. If the Habsburg original label is detached, it is placed next to the sample. This exhibition design was adopted to promote cross-cultural learning [

105] since science and humanities teachers can organize learning activities based, for instance, on comparing the historical mineral naming and its modern characterization. In this regard,

Table 1 illustrates the historical mineralogical classification assigned to the surviving specimens from the collection donated by Joseph II to the Collegio Nazareno in 1785. Here, diverse ancient mineral names are listed (e.g., blende). Starting from this information, science teachers can organize learning activities involving directly observing the minerals to identify the modern names while explaining the historical ones. Furthermore, activities focusing on the history of mining, technology, and people in the 18th-century Habsburg domains can be offered to high school students using the data retrieved from the cataloging campaign. Finally, the last three showcases display the most scientifically interesting rock samples. In this regard, diverse specimens from Roman and Latium mines are noteworthy since they represent helpful nature-based objects to teach local mining history starting from primary schools, thus helping to develop a sense of place between pupils and students [

106,

107,

108]. The activities mentioned above and the compilation of new cataloging records on the stored specimens can be the topic of the brief essay students have to prepare for their high school graduation exams. As suggested by Colletti [

109,

110] concerning physics education, multiple cultural contexts can positively contribute to promoting geo-mineralogical sciences, even among students who do not plan to pursue a career in science. The display cases are then interspersed with four educational panels, easy-to-read and drawn using text characters readable also by visually impaired people, which report a brief history of the Collegio Nazareno’s Mineralogical Cabinet, notes on Habsburg mineral collecting, a comprehensive reconstruction of events surrounding the donation of the mineralogical collection from Joseph II to the Collegio Nazareno in 1785, and a detailed explanation of the exhibition setting.

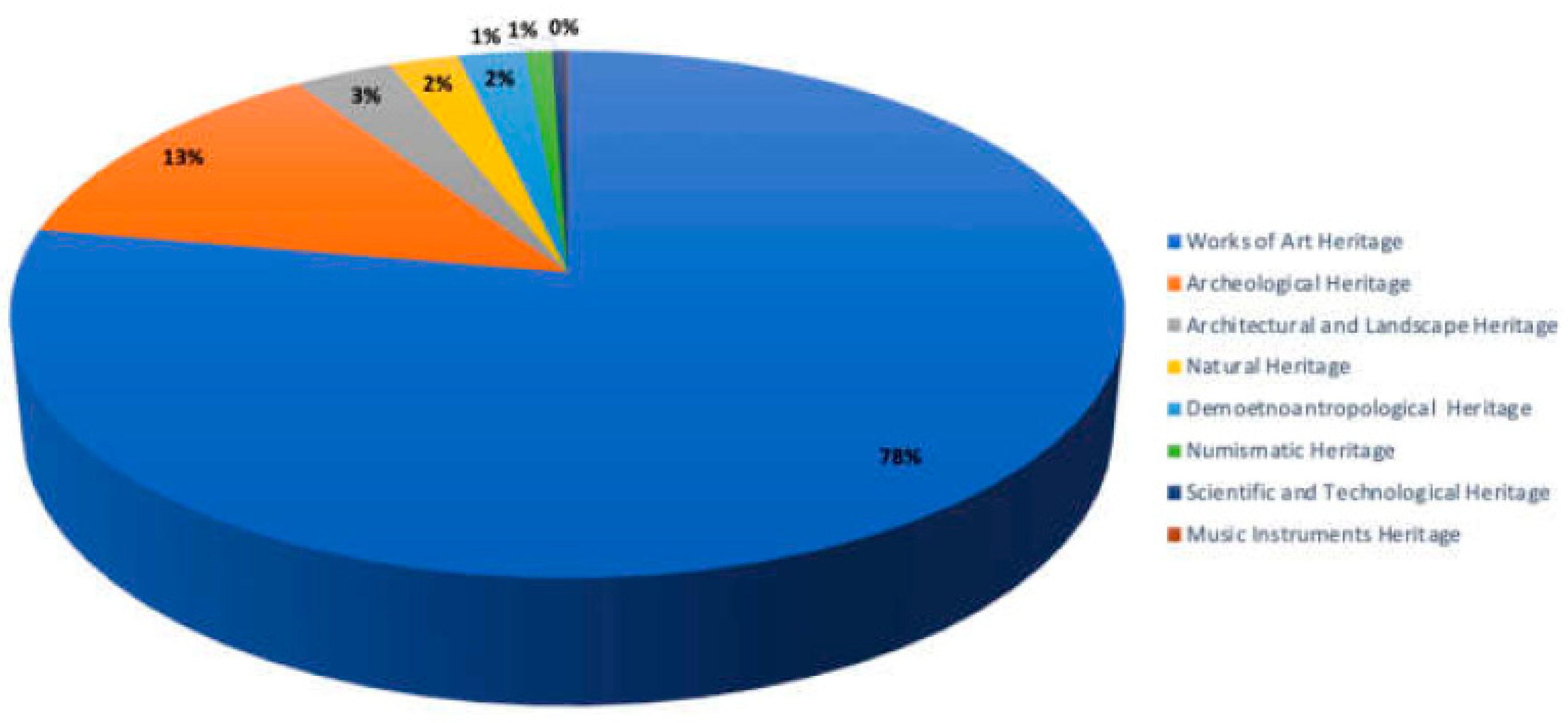

In the roundtable organized during the workshop aimed to illustrate the project’s findings, both students and teachers agreed on how cataloging natural history collections with ICCD national standards represented an effective tool to safeguard, preserve, and valorize through the publication of the catalog records in OA on the CGBC database, the Italian scientific school heritage. CGBC currently contains 2917801 records categorized according to the different types of cultural properties composing the Italian cultural heritage, as shown in

Figure 6.

Browsing the CGBC database by keywords, it is found that the term «school» (scuola) retrieved 675 catalographic records. Among these, 60 records concern the cataloging of the rock collection kept in the Istituto Tecnico Industriale Michelangelo Buonarroti, a secondary school in Caserta [

111]. The remaining records are related to university museums such as the Museo di Anatomia Patologica e Paleopatologia of the University of Pisa [

112], which cataloged 387 morbid anatomy specimens using the AT national standard.

Searching the CGBC natural heritage database for «school institute» (istituto scolastico), 1078 records are retrieved, most related to herbals whose folia were cataloged using the BNB national standard. The most interesting aspect of this finding is that the herbals were part of school teaching collections such as the Istituto Magistrale “Isabella Gonzaga,” a secondary school for training primary teachers in Chieti. The natural history collections – also comprising taxidermized specimens, wood samples, fruit, and mushroom models – are now preserved at the Museo Universitario of the University of Chieti together with the scientific instruments coming from the laboratories of both the Istituto Magistrale “Isabella Gonzaga” and the Liceo Classico “G.B. Vico” [

113]. For the remaining herbals, 502 catalog records belong to the Istituto di Istruzione Secondaria Superiore “G.B. Cerletti” of Conegliano, in the province of Treviso. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the cataloged volumes are still preserved in the school.

The keyword «high school» (liceo) returned 125 catalog records, the majority of which are represented by zoological specimens (ca. 115 samples) that were part of the natural history teaching collections of the Liceo Classico “G.B. Vico” in Chieti and therefore are now housed at the Museo Universitario.

This survey suggested that cataloging natural history teaching collections using the ICCD national standard for natural heritage is an effective tool for safeguarding, preserving, and valorizing school heritage. In this regard, the cataloging campaign at the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio added to the CGBC database 187 cataloging records regarding mineralogical specimens and 13 cataloging records concerning rock samples.

5. Conclusions

The present research aimed to recover, preserve, and valorize the 18th-century geo-mineralogical collection belonging to the Mineralogical Cabinet of the Collegio Nazareno and now housed at the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio of Rome.

This study has identified 1724 specimens at risk of loss and damage, including 59 samples from the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph’s II collection donated to the Mineralogical Cabinet in 1785. The latter was one of the most significant findings from this study since no other mineralogical collections can be currently credited to Joseph II.

All the recovered specimens were inventoried in an offline database providing scientific, historical, and technical information retrieved by studying the specimens and the archival material (e.g., inventories, catalogs, and display labels). About 100 specimens were treated with basic remedial conservation remedies. A catalog campaign concerning 200 specimens was performed using the ICCD national standards for cataloging minerals (BNM) and rocks (BNPE). The results of this operation showed that as occurred in other fields of science education and museum studies [

114,

115,

116], the geo-mineralogical specimens can be positively used as scientific-educational tools in object-based learning experiences and cross-cultural student activities to promote science literacy [

117].

Overall, this study strengthens the idea that cataloging natural history school collections, especially those kept in private and religious institutes, using the seven ICCD national standards for the cataloging of natural heritage (e.g., BNM, BNPE, BNPL, BNP, BNZ, BNB, and AT) is a valuable tool for tracing, recovering, preserving, and valorizing these unique nature-objects.

In conclusion, as suggested by Brunelli [

118], cataloging campaigns involving students when teaching collections are present should be encouraged and related to the curricular activities to improve the knowledge of school heritage, promote science learning, and help teachers, educators, and museum operators to safeguard and make accessible these collections to anyone interested in learning more about the history of science education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization Annarita Franza and Giovanni Pratesi; writing—original draft preparation, Annarita Franza; writing—review and editing, Giovanni Pratesi.

Funding

This research was founded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research Grant n. PANN20_0065.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Istituto San Giuseppe Calasanzio staff.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Semper, R.J. Science museums as environments for learning. Phys. Today 1990, 43, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellington, J. Formal and informal learning in science: The role of the interactive science centers. Phys. Edu. 1990, 25, 247–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P.M. Topics in Museums and Science Education. Stud. Sci. Educ. 1992, 20, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey-Gassert, L.; Walberg III, H.J.; Walberg, H.J. Reexamining connections: Museums as science learning environments. Sci. Educ. 1994, 78, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, L.; McClafferty, T. Using visits to interactive science and technology centers, museums, aquaria, and zoos to promote learning in science. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 1995, 6, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.; Symington, D. Moving from task-oriented to learning-oriented strategies on school excursions to museums. Sci. Educ. 1997, 81, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey-Gassert, L. Learning Science beyond the Classroom. Elem. Sch. J. 1997, 97, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, N.; Eilks, I. The expectations of teachers and students who visit a non-formal student chemistry laboratory. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2015, 11, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.J.; Durksen, T.L.; Williamson, D.; Kiss, J.; Ginns, P. The role of a museum-based science education program in promoting content knowledge and science motivation. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2016, 53, 1364–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heering, P. Science Museums and Science Education. Isis 2017, 108, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, T.; Lawrence, M.; Oliver, M.; Reiss, M.J. Learning and engagement through natural history museums. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2018, 54, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnette, R.N.; Crowley, K.; Schunn, C.D. Falling in love and staying in love with science: ongoing informal science experiences support fascination for all children. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2019, 41, 1626–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, M.; Knutson, K.; Crowley, K. Becoming a naturalist: Interest development across the learning ecology. Sci. Educ. 2019, 103, 691–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, B.; Gupta, P.; Levine, B.; Adams, J. An Informal Science Education Program’s Impact on STEM Major and STEM Career Outcomes. Res. Sci. Educ 2020, 50, 1051–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta, F.; Pecora, F.; Prete, G.; Settino, A.; Carbone, V.; Riccardi, P. A bridge between research, education and communication. Nat. Astron. 2020, 4, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilhab, T. Nature experiences in science education in school: Review featuring learning gains, investments, and costs in view of embodied cognition. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 739408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenici, V. STEAM Project-Based Learning Activities at the Science Museum as an Effective Training for Future Chemistry Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, D.; Öztürk, N. Preparing to teach in informal settings: preservice science teachers’ experiences in a natural history museum. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2022, 44, 2724–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenici, V. Training of future chemistry teachers by a historical / STEAM approach starting from the visit to an historical science museum. Substantia 2023, 7, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rende, K.; Jones, M.G.; Refvem, E.; Carrier, S.J.; Ennes, M. Accelerating high school students’ science career trajectories through non-formal science volunteer programs. Int. J. Sci. Educ. B Commun. Public Engagem. 2023, 13, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, P. How to restore trust in science through education. Nat. Physi. 2023, 19, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.W. The school museum. Sci. Educ. 1931, 15, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, E. All the World into the School: World's Fairs and the Emergence of the School Museum in the Nineteenth Century. In Modelling the Future. Exhibitions and the Materiality of Education; Lawn, M., Ed.; Comparative Histories of Education, Symposium Books: London, United Kingdom, 2009; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine, A.; Matasci, D. Centraliser, exposer, diffuser: les musées pédagogiques et la circulation des savoirs scolaires en Europe (1850-1900). Revue germanique internationale 2015, 21, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.; Driver, F. Kew Gardens and the emergence of the school museum in Britain, 1880–1930. Hist. J. 2020, 63, 1204–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, K. The method of Anschauung: from Johann H. Pestalozzi to Herbert Spencer. J. Educ. Thought 2003, 37, 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cornish, C.; Driver, F. ‘Specimens Distributed’ The circulation of objects from Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany, 1847–1914. J. Hist. Collect. 2020, 32, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, C.A. Curating duplicates: operationalizing similarity in the Smithsonian Institution with Haida rattles, 1880–1926. Br. J. Hist. Sci. 2022, 55, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero-Urtaza, E.; Manuel, B. Cossío’s 1882 tour of European education museums. Paedagog. Hist. 2012, 48, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantoni, L.; Poggi, L. Dal Gabinetto di Mineralogia al Museo di Storia Naturale. In Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze: Le collezioni mineralogiche e litologiche; Pratesi, G., Ed.; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2012; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, P.M.L. The National Pedagogical Museum and educational renewal in Spain (1882-1941)

. Cad. Hist. Educ. 2022, 21, e102. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ascenzo, M. Linee di ricerca della storiografia scolastica in Italia: la storia locale. Espac. Tiempo Educ. 2016, 3, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzo, M. Il patrimonio storico-educativo per la formazione docente. Esperienze tra ricerca e didattica. Educació i Història: Revista d’Història de l’Educació 2022, 39, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzigoni, F.D. Imparare a imparare attraverso il museo scolastico: tracce di nuove potenzialità di uno strumento didattico tardo-ottocentesco. Form@re - Open Journal Per La Formazione in Rete 2015, 15, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Meda, J. Mezzi di educazione di massa. Saggi di storia della cultura materiale della scuola tra XIX e XX secolo; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, M. Alle origini del museo scolastico. Storia di un dispositivo didattico al servizio della scuola primaria e popolare tra Otto e Novecento; EUM: Macerata, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, M.; Panizza, G.; Morandi, M. I beni culturali della scuola: conservazione e valorizzazione, sezione monografica. Annali di storia dell’educazione e delle istituzioni scolastiche 2008, 15, 15–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sega, M.T. (Ed.) La storia fa la scuola. Gli archivi scolastici per la ricerca e la didattica; Nuova Dimensione: Portogruaro, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ascenzo, M. Gli archivi scolastici come fonti per la ricerca storico-educativa: esperienze e prospettive. Hist. Educ. Child. Lit. 2021, 16, 751–772. [Google Scholar]

- Barsotti, S.; De Serio, B.; Lepri, C.; Mattioni, I.; Merlo, G. Le biblioteche scolastiche in Italia: un’ipotesi di ricerca sul patrimonio storico-educativo. Cabás 2023, 29, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Meda, J. Musei della scuola e dell’educazione. Ipotesi progettuale per una sistematizzazione delle iniziative di raccolta, conservazione e valorizzazione dei beni culturali delle scuole. Hist. Educ. Child. Lit 2010, 489–501. [Google Scholar]

- Borruso, F.; Brunelli, M. Il Museo racconta la scuola tra passato e presente. In La Public History tra scuola, università e territorio. Una introduzione operativa; Bandini, G., Bianchini, P., Borruso, F., Brunelli, M., Oliviero, S., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2022; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cantatore, L. Storia e vita del MuSEd–Museo della Scuola e dell’Educazione dell’Università Roma Tre. Educació i Història: revista d'història de l'educació 2022, 39, 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Merlo, G.; Targhetta, F. Il Museo dell’Educazione dell’Università di Padova. Ragioni, finalità e criteri ispiratori delle collezioni e delle attività. In La Práctica Educativa. Historia, Memoria y Patrimonio; Gonzalez, S., Meda, J., Motilla Salas, X., Pomante, L.A., Eds.; FahrenHouse Ediciones: Cabrerizos, Spain, 2018; pp. 960–970. [Google Scholar]

- Loparco, F. The MUSLI Museo della Scuola e del Libro per l'Infanzia (The School and the Children's Book Museum) of the Foundation Tancredi di Barolo in Turin: an Institution at the Forefront of the Preservation and Enhancement of Educational and Scholastic Heritage. Hist. Educ. Child. Lit. 2013, 8, 795–818. [Google Scholar]

- Debe, A.; Riva, A. Le carte che fanno scuola: il patrimonio storico-educativo a servizio della didattica nell’esperienza dell’Archivio di Stato di Piacenza. In Il patrimonio storico-educativo come risorsa per il rinnovamento della didattica scolastica e universitaria: esperienze e prospettive. Atti del 2° Congresso Nazionale della Società Italiana per lo studio del Patrimonio Storico-Educativo (Padova, 7-8 ottobre 2021); Ascenzi, A., Covato, C., Zago, G., Eds.; EUM: Macerata, Italy, 2021; pp. 577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi, A.; Brunelli, M.; Meda, J. School museums as dynamic areas for widening the heuristic potential and the socio-cultural impact of the history of education. A case study from Italy. Paedagog. Hist. 2021, 57, 419–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, M.; Targhetta, F. Il nuovo Museo della Scuola “Paolo &Ornella Ricca”: un'infrastruttura per la didattica, la ricerca e la terza missione. In Nuevas miradas sobre el patrimonio historico-educativo. Audiencias, narrativas y objetos educativos; Ortiz Garcia, E., Gonzalez de la Torre, J.A., Saiz Gomez, J.M., Naya Garmendia, L.M., Davila Balsera, P., Eds.; Gobierno de Cantabria-Sephe-Crieme: Santander, Spain, 2023; pp. 652–672. [Google Scholar]

- D'Alessio, M.; Andreassi, R.; Barausse, A. Museo della Scuola e dell'educazione popolare Università degli Studi del Molise-Campobasso, Italia. Cabás 2016, 2, 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, M. La recente costituzione della Società Italiana per lo Studio del Patrimonio Storico-Educativo (SIPSE). Hist. Educ. Child. Lit. 2017, 12, 653–665. [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi, A.; Patrizi, E.; Targhetta, F. La promozione e la tutela del patrimonio storico-educativo sul territorio. L’esperienza della Società Italiana per lo Studio del Patrimonio Storico-Educativo (2017-2022). In Nuevas miradas sobre el patrimonio historico-educativo. Audiencias, narrativas y objetos educativos; Ortiz Garcia, E., Gonzalez de la Torre, J.A., Saiz Gomez, J.M., Naya Garmendia, L.M., Davila Balsera, P., Eds.; Gobierno de Cantabria-Sephe-Crieme: Santander, Spain, 2023; pp. 753–767. [Google Scholar]

- Barausse, A.; Callegari, C.; Cantatore, C.; Morandini, M.C.; Targhetta, F. Musei scolastici e collezioni scientifiche delle Scuole: censire, conservare e valorizzare il patrimonio storico scolastico. In Nuevas miradas sobre el patrimonio historico-educativo. Audiencias, narrativas y objetos educativos; Ortiz Garcia, E., Gonzalez de la Torre, J.A., Saiz Gomez, J.M., Naya Garmendia, L.M., Davila Balsera, P., Eds.; Gobierno de Cantabria-Sephe-Crieme: Santander, Spain, 2023; pp. 733–752. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, M.; Paoletti, A.; Robotti, N. Patrimoni da valorizzare: gli strumenti storico-scientifici delle scuole e degli osservatori della Liguria. Museologia Scientifica 2008, 2, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Marcon, F.; Talas, S. Progetto di alternanza scuola-lavoro per la valorizzazione di strumenti scientifici storici. Museologia Scientifica 2019, 13, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gallitto, A.A.; Zingales, R.; Battaglia, O.R.; Fazio, C. An approach to the Venturi effect by historical instruments. Phys. Educ. 2021, 56, 025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallitto, A.A.; Battaglia, O.R.; Cavallaro, G.; Lazzara, G.; Lisuzzo, L.; Fazio, C. Exploring historical scientific instruments by using mobile media devices. Phys. Teach. 2022, 60, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, P.; Romano, V.; Pellegrino, F. Interactions among school teachers, students and university researchers in workplace experiences using disused instruments of school laboratories. Phys. Educ. 2022, 57, 045006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, P.; Romano, V.; Pellegrino, F. Education and public outreach through vacuum science and technology. Vacuum 2022, 196, 110737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, P.; Prete, G.; Chiappetta, F.; Meringolo, C. Wireless at its origin. Phys. Educ. 2022, 58, 015024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelini, M.; Malgieri, M.; Corradini, O.; De Angelis, I.; Falomo Bernarduzzi, L.; Giliberti, M.; Pagliara, S.; Pavesi, M.; Sabbarese, C.; Salamida, F.; Straulino, S.; Immè, J. An overview of physics teacher professional development activities organized within the Italian PLS-Physics plan over the past five years. J. Phys. Conf. Ser 2297, 012030. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnucci, L.; Spigarelli, F. The Third Mission of the university: A systematic literature review on potentials and constraints. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcarini, M.F. Promuovere le soft skills con i PCTO (Percorsi per le Competenze Trasversali e l’Orientamento). Una proposta operativa: progettazione collaborativa degli spazi scolastici mediante l’auto-organizzazione degli studenti. Rivista di filosofia e pratiche educative 2022, 1, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Francescangeli, R.; Montenegro, V.; Garuccio, A. Una riflessione sull’esperienza di alternanza scuola-lavoro presso il Sistema Museale di Ateneo dell’Università di Bari. Museologia Scientifica 2018, 12, 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Galetto, M. Alternanza scuola-lavoro al MUSE, Museo delle Scienze di Trento. Testimonianze e riflessioni. Museologia Scientifica 2018, 12, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Signore, G.M.; Melissano, V.; Notario, C. L’esperienza di alternanza scuola-lavoro nei musei, laboratori e biblioteche del Dipartimento di Beni Culturali dell’Università del Salento. Museologia Scientifica 2018, 12, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, A.; Paolucci, A.; Del Cimmuto, M.; Icaro, I.; Di Fabrizio, A.; Capasso, M.C.; Cilli, J. Il patrimonio storico-culturale del Museo universitario di Chieti per l’alternanza scuola-lavoro. Museologia Scientifica 2019, 20, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gilli, E.; Vaccari, G. Alternanza scuola-lavoro: il museo una risorsa per la scuola, la scuola una risorsa per il museo. Museologia Scientifica 2019, 18, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Brutto, S.; Tarantino, A.; Tumbiolo, M.L.; Lo Vullo, R. Progetto di alternanza scuola-lavoro per la valorizzazione di collezioni zoologiche. Museologia Scientifica 2019, 13, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Maretti, S.; Guaschi, P.; Coladonato, A.; Maffei, J.; Razzetti, E.; Trifogli, A.; Siviero, M. Il progetto di alternanza scuola-lavoro del Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di Pavia. Museologia Scientifica 2019, 19, 149–151. [Google Scholar]

- Tepedino, C.; Maramaldo, R.; Gambarelli, A.; Corradini, E. Animali in posa. Un’esperienza di alternanza scuola-lavoro del Polo Museale UNIMORE per l’inclusività e l’accessibilità del patrimonio culturale zoologico. Museologia Scientifica 2020, 21, 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Adamo, I.; Duraccio, S.; De Tommaso, F. Note preliminari sulle collezioni zoologiche dell’Istituto Bianchi dei Padri Barnabiti di Napoli. Atti della Società dei Naturalisti e Matematici di Modena 2020, 151, 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci, P. Il Collegio Nazareno 1630-1930; S.n.: Roma, Italy, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Armando, D. Gli Scolopi nelle istituzioni della Repubblica Romana del 1798-1799. Studi Romani 1992, 40, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Donato, M.P. Accademie romane. Una storia sociale (1671-1824); Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Roma, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Farinella, C. Gandolfi, Bartolomeo. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani 1999, 52, 159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Maddaluno, L. Materialising political economy: olive oil, patronage and science in Eighteenth-century Rome. Diciottesimo Secolo 2020, 5, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, G.V. Gabinetto mineralogico del collegio Nazareno descritto secondo i caratteri esterni e distribuito a norma de' principj costitutivi; Lazzarini: Roma, Italy, 1791–1792; 2 volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Renazzi, F.M. Storia dell’Università di Roma detta comunemente La Sapienza che contiene anche un saggio storico della letteratura romana; Nella Stamperia Pagliarini: Roma, Italy, 1805; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Burdet, C.A.M. Carlo Antonio Napione (1756-1814): artigliere e scienziato in Europa e in Brasile, un ritratto; Celid: Torino, Italy, 2005; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Raggio, O. Storia di una passione. Cultura aristocratica e collezionismo alla fine dell’ancien régime; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, C. Felice Fontana and the formation of the naturalistic collections of the Imperial royal museum of physics and natural history of Florence. Nuncius 2006, 21, 251–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolini, R.G.; Ongano, G. Espistolario di Felice Fontana. Carteggio con Leopoldo Marc’Antonio Caldani; Società di Studi Trentini di Scienze Storiche: Trento, Italy, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Riccomini, A.M. Il viaggio in Italia di Pietro De Lama; Edizioni ETS: Pisa, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Venturini, D. Museo Mineralogico dell’Archiginnasio Romano. Il Vero Amico del Popolo 1856, 54, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, G.; Mattias, P.; Ruali, P.M. Il Museo Naturalistico Mineralogico del Collegio Nazareno. Il Cercapietre 1997, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Insulander, E.; Thorsén, D. Teaching through objects and collections: The case of Strängnäs Secondary Grammar School and school museum 1830-1960. Multimodality & Society 2023, 26349795231185957. [Google Scholar]

- Nasti, V. Ad maiora! Il Cercapietre 2012, 1-2, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Casto, L.; Celi, M.; Ferrante, F.; Francescangeli, R.; Pesce, G.B.; Pezzotta, F.; Pizzo, M.; Pratesi, G.; Scandurra, P.; Zorzin, R. Scheda BNM. Beni Naturalistici – Mineralogia; ICCD: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Armiraglio, S.; Cuccuini, P.; Del Lago, A.; Macinelli, M.L.; Martellos, S.; Pesce, G.B.; Scandurra, P. Scheda BNB. Beni Naturalistici – Botanica; ICCD: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Agnelli, P.; Barbagli, F.; Biddittu, A.; Brugnoli, A.; Calandra, V.; Castellani, P.; Ferrante, F.; Latella, L.; Mizzan, L.; Muscio, G.; Pesce, G.B.; Scali, S.; Scandurra, F. Scheda BNZ. Beni Naturalistici – Zoologia; ICCD: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Angelelli, F.; Barbagli, F.; Corradini, E.; Cioppi, E.; D’Arpa, C.; Del Favero, L.; Ferrante, F.; Fornasiero, M.; Fresina, A.; Maganuco, S.; Mancinelli, M.L.; Matteucci, R.; Minervini, E.; Muscio, G.; Ormezzano, D.; Pizzo, M.; Rossi, R.; Russo, A.; Tintori, A.; Scandurra, P.; Vasco, S. Scheda BNP. Beni Naturalistici – Paleontologia; ICCD: Roma, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baggieri, G.; Baldelli, G.; Bergamini, G.; Bianchin Citton, E.; Bondioli, L.; Capasso, L.; Caramiello, S.; Catalano, P.; Mancinelli, M.L.; Mazzitelli, P.; Miele, F.; Nicolai, R.M.; Nista, L.; Pacciani, E.; Poggiani Keller, R.; Rubini, M.; Salvadei, L. Scheda AT, reperti antropologici; ICCD: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Casto, L.; Celi, M.; Ferrante, F.; Francescangeli, R.; Pesce, G.B.; Pezzotta, F.; Pizzo, M.; Pratesi, G.; Scandurra, P.; Zorzin, R. Scheda BNPL. Beni Naturalistici – Planeologia; ICCD: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Casto, L.; Celi, M.; Ferrante, F.; Francescangeli, R.; Pesce, G.B.; Pezzotta, F.; Pizzo, M.; Pratesi, G.; Scandurra, P.; Zorzin, R. Scheda BNPE. Beni Naturalistici – Petrologia; ICCD: Roma, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pratesi, G.; Franza, A. Mineralogical, petrological and planetological heritage. The (Italian) story so far. Rendiconti Lincei 2021, 32, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiderio, M.L.; Mancinelli, M.L.; Negri, A.; Plances, E.; Saladini, L. Il SIGECweb nella prospettiva del catalogo nazionale dei beni culturali. DigItalia 2013, 8, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Veninata, C. Dal Catalogo generale dei beni culturali al knowledge graph del patrimonio culturale italiano: il progetto ArCo. DigItalia 2020, 15, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, C.; Horak, J. Storage and conservation of geological collections—a research agenda. J. Inst. Conserv. 2018, 41, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.J. Objects and the Museum. Isis 96, 559–571. [CrossRef]

- Mottana, A.; Mussino, A.; Nasti, V. Minerals from the Carpathian Mountains and from Transylvania donated by Joseph II (1785) to the Museum of the Collegio Nazareno, Rome, Italy. Cent. Eur. Geol. 2012, 55, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franza, A.; Pratesi, G. Dono imperiale. La collezione mineralogica dell’imperatore Giuseppe II al Collegio Nazareno di Roma. Firenze University Press:: Firenze, Italy, in press.

- Wilson, W.E. Ignaz Edler von Born (1742-1791). The Mineralogical Record 1994, 25, 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S. Designs for learning: Studying science museum exhibits that do more than entertain. Science Education 2004, 88, S17–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid-Griffin, A. Learning the Language of Earth Science: Middle School Students' Explorations of Rocks and Minerals. Eur. J. STEM Educ. 2016, 1, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, C.; Driver, F.; Nesbitt, M.; Willison, J. Revitalizing the school museum: Using nature-based objects for cross-curricular learning. J. Mus. Educ. 2021, 46, 334–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, L.; Mates, L. ‘Making Heritage Matter’? Teaching local mining history in primary schools. Educ. 3 13 2020, 50, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimshaw, L.; Mates, L. ‘It’s part of our community, where we live’: Urban heritage and children’s sense of place. Urban Stud. 2022, 59, 1334–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K. The industrial past as a tool of possibility: Schooling and social class in a former coalfield community. Sociol. Rev. 2023, 71, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colletti, L. The Italian secondary-school graduation exam: Connecting physics with the humanities. Phys. Educ. 2020, 56, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colletti, L. Making physics teaching inclusive through a humanistic approach. Phys. Educ. 2022, 4, 2250016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, P. Guida al Museo Michelangelo di Caserta: percorsi di visita nella storia della scienza, della tecnologia e della didattica; Melagrana: San Felice a Cancello, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Minozzi, S.; Landini, L.; Naccarato, G.; Giuffra, V. Restoration and preservation of the anatomical specimens of the Museum of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Pisa. PATHOLOGICA 2017, 109, 430. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabrizio, A.; Paolucci, A.; Capasso, L.; D’Anastasio, R.; Del Cimmuto, M.; Fazio, A.; Cesana, D.; Sciubba, M. Scientific research in the University Museum of Chieti. Atti della Società Toscana di Scienze Naturali - Memorie Serie B 2012, 119, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.A.; Edwards, S.V.; Lacey, E.A.; Guralnick, R.P.; Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E.; Welch, C.K.; Bell, K.C.; Galbreath, K.E.; Himes, C.; Allen, J.M.; Heath, T.A.; Carnaval, A.C.; Cooper, K.L.; Liu, M.; Hanken, J.; Ickert-Bond, S. Natural history collections as emerging resources for innovative education. BioScience 2014, 64, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfils, A.K.; Powers, K.E.; Marshall, C.J.; Martine, C.T.; Smith, J.F.; Prather, L.A. Natural history collections: Teaching about biodiversity across time, space, and digital platforms. Southeast. Nat. 2017, 16, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peers, L.; Vitelli, G. Teaching anthropology with museum collections. Teaching Anthropology 2020, 9, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugksch, R.C. Scientific literacy: A conceptual overview. Sci. Educ. 2000, 84, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, M. La catalogazione didattica: proporre attività di prima catalogazione da collegare alle attività scolastiche. In Il passaggio necessario: catalogare per valorizzare i beni culturali della scuola. Primi risultati del lavoro della Commissione tematica SIPSE; Pizzigoni, F.D., Brunelli, M., Eds.; EUM: Macerata, Italy, 2023; pp. 119–152. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).