1. Introduction

Pregnancy is a special time in a woman’s life. It brings physiological changes in her body and emotional and social challenges to her mind. Feelings of happiness are mixed with concern about what will life change bring and whether pregnancy and birth will go easily while looking for methods to alleviate both. Practicing yoga during pregnancy provides many benefits. According to growing evidence from the literature, yoga appears to help pregnant women in terms of developing mental and physical health and building a connection with their unborn babies [

1,

2,

3].

The process of childbirth is challenge for the body and mind. Yoga in pregnancy is a method that lowers maternal fear and anxiety during labour and enables pregnant women to go through delivery without using epidural analgesia or medication [

4,

5]. Yoga seems to help reduce the intensity of pain and helps pregnant women to be in control of their labour, increasing their satisfaction with it. Additionally, it brings them a feeling of self-confidence and empowerment [

4].

Practicing yoga helps to alleviate pregnancy symptoms. It decreases back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms, nausea, headaches and shortness of breath, improves sleep and increase strength, flexibility and endurance of muscles needed for childbirth [

1].

Yoga is a suitable activity for pregnant women, due to its nature of body and mind practice. It’s a system of various poses (asana) and stretching exercises, combined with breathing (pranayama) and meditation (dharana) [

6].

ACOG recommends obstetricians, gynaecologists, midwives, labouring women, nurses and all supporters of labouring women, to use methods during labour that need minimal intervention and have high rates of woman satisfaction [

7]. Among such interventions, ACOG recommends, for term pregnant women in spontaneous delivery with a vertex-presented foetus, relaxation techniques as one of the nonpharmacological methods for pain relief. Within nonpharmacological methods, the one with the best relaxation component is yoga, enabling women to work and cope with labour pain as opposed to pharmacologic methods that mitigate labour pain. Precisely, fear and anxiety reduce women’s self-confidence and empowerment which is important during the process of labour [

7].

At the same time, the incredible increase in the number of CS presents a great challenge to modern obstetrics with the number rising around the world, and with an average rate increase of 19% from 1990-2018 and continuing to rise globally having the highest rate of 57.55% in Turkey [

8]. South American countries have quite similar rates. In Brazil, the overall CS rate was reported as 55.8%. In Europe, CS rates increased from 11.2% to 25% [

9]. Around the world in general, there is a 21.1% CS rate, with a big difference among countries [

8]. In Europe we have a 25.7% CS rate with projected of rise to 47% in Southern Europe and 27.6% in Northern Europe. Such a big rise in operative delivery is not supported by better neonatal and maternal outcomes [

9]. CS is a lifesaving procedure for mother and child when medically indicated [

10]. However, evidence shows that the procedure is overused and brings no benefit for mother and child [

8,

10].

In recent years clinicians have expressed concerns about the increasing number of CS deliveries and the potential negative consequences of CS for maternal and child health. The increasing caesarean delivery rate worldwide is followed by increased maternal morbidity due to pathological placentation, peripartum hysterectomy and obstetric bleeding [

11].

It’s estimated that the global average CS rate will increase from 21.1%–28.5% till 2030 with more than 38 million caesarean births in 2030 [

8]. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) published recommendations for the optimization of foetal and maternal outcomes, suggesting that targeted caesarean delivery rates should not exceed 10–15 per 100 live births [

12].

Molina et. al, produced a revision of the WHO recommendations. They found that the limits were set too low and that the national CS rate of approximately 19% was linked to lower maternal or neonatal mortality among WHO member states [

13].

The prevention of unnecessary CS continues to be a global priority. Various strategies have been implemented to reduce the proportion of CS to a reasonable level. Evidence suggests that yoga during pregnancy is safe for pregnant women and may be more beneficial than walking and standard prenatal exercises for both physical and mental health [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The introduction of prenatal yoga with evidence-based clinical interventions may have a greater effect on the CS rate than other features justifying the increase in occurrences of CS [

18,

19,

20]. Since a limited number of studies focus on impact of yoga practice during pregnancy on intrapartum CS rate, we aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the non-clinical intervention of yoga practice during pregnancy, in order to determine the value of such an intervention in reducing intrapartum emergent CS rates among healthy singleton primiparas who practice yoga during pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study setting

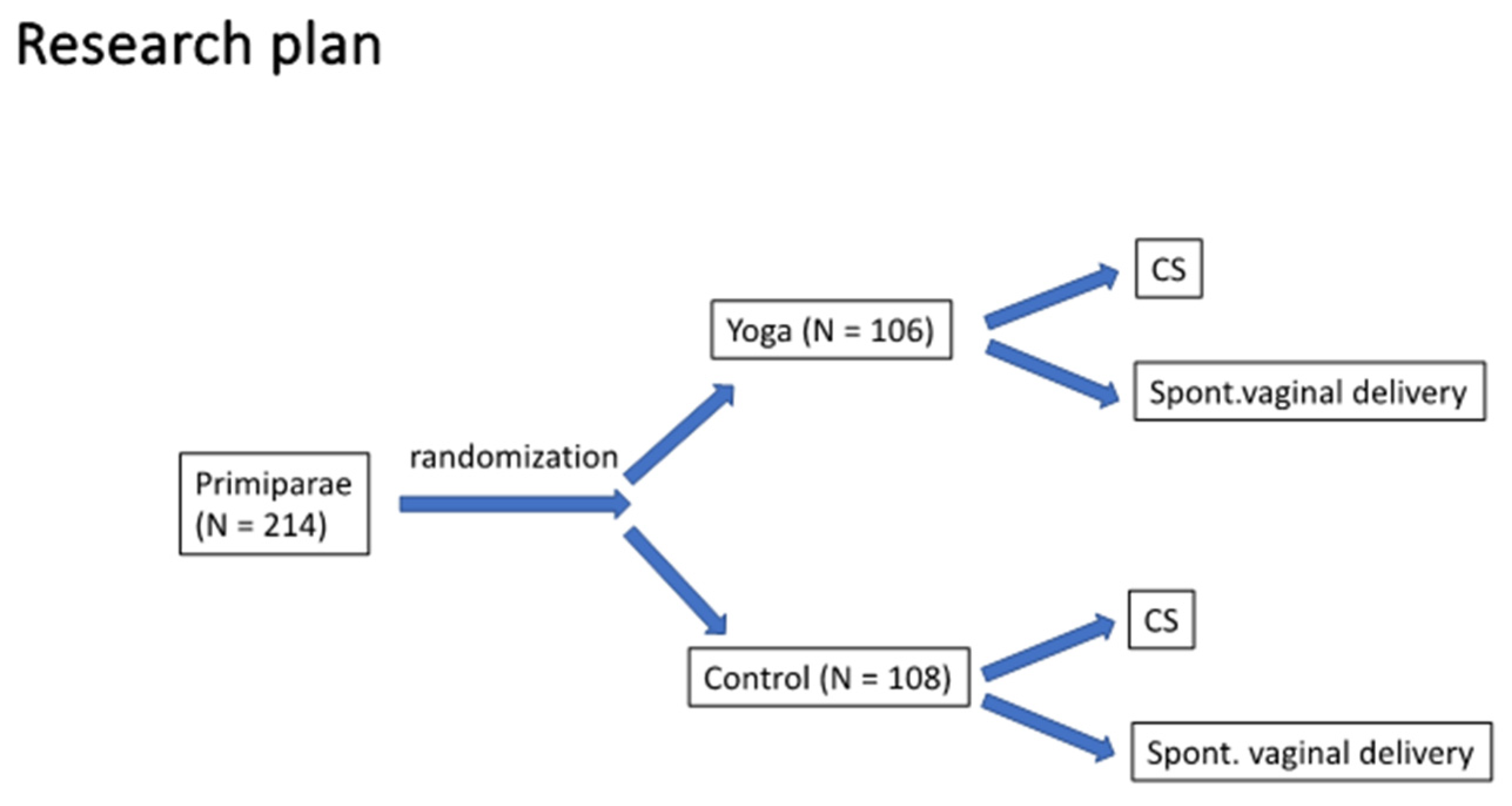

This prospective, single-blinded, randomized controlled clinical trial was conducted at the University Medical Centre Maribor, Division of Gynaecology and Perinatology between May 2019 and September 2023. The Ethics Committee of the Maribor University Clinical Centre gave written consent and approval under Number UKC-MB-KME-29/17. The trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with identifier no.: NCT03941041. All women gave informed, written consent to take part in the study. The research plan is presented in

Figure 1. The study included healthy primiparous women aged 18 or more with a singleton pregnancy and the gestational age prior-to 14 weeks. In order to achieve appropriate group homogeneity, we only recruited pregnant women between 20–35 years of age who did not practice yoga outside of pregnancy (“yoga naive”), with a body mass index (BMI) of 18–30 kg/m

2 and a body height of above 160 cm. During the recruitment, pelvic measurements were assessed and only women with normal pelvic measurements were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were the presence of a multiple pregnancy, pregnancy with foetal malformations, vaginal bleeding, cervical insufficiency, cerclage, placenta previa, chronic diseases (hypertension, diabetes tip I and II, epilepsy, heart and lung diseases, haematological diseases), any anomaly of the reproductive system and pregnant women who practice yoga outside of pregnancy. Patients were recruited during regular antenatal visits at their gynaecologist’s office in the region of Maribor. Singleton primiparas up to 14 weeks of pregnancy were invited to participate in the study. After receiving detailed information about the project and after informed consent was given and signed, patients were randomized by the head researcher’s assistants.

2.2. Randomization

Randomization was performed by a draw of closed, opaque envelopes, which contained the group allocation. After consent was given, the pregnant women got sequential code. After that they drew an envelope and were allocated to one of the study arms: the study group (pregnant women who received standard antenatal care and practiced yoga during pregnancy) and the control group (pregnant women who received standard antenatal care). The researchers did not have any ability to influence the group selection. The staff in the delivery rooms and the end data evaluators were blind to the group selection.

2.3. Clinical parameters

Maternal demographic data included: maternal age, body mass index (BMI) at the time of randomization, BMI at the time of delivery, enlargement of BMI during pregnancy and the level of maternal education. Labour parameters included: gestation age at the time of delivery, foetal presentation, onset of labour, mode of delivery, operative delivery, rate of episiotomy, rate of small (1–2 degree) and rate of severe (3–4 degree) perineal rupture. Oxytocin usage in the first and or second stage of labour, maximal doses of oxytocin used at the delivery, rate of interest for epidural analgesia at the time of admission to the maternity ward, rate of usage of intravenous or epidural analgesia. We also recorded the Visual Analogue Scale score (VAS) for labour pain at the end of the latent phase of the first stage of labour, before the application of epidural analgesia and/or intravenous analgetic when the cervix was dilated between 3-6 cm. VAS is the scale for rating the severity of pain and has 11 points. From 0 (= no pain) to 10 (= most severe pain imaginable).

We measured the duration of labour in minutes from the beginning of regular uterine contraction till the delivery of the baby.

From the delivery records were obtained data about indication for urgent intrapartum CS, dilatation of cervix uteri before urgent CS and rates of pathological cardiotocograph (CTG) according to the FIGO classification [

21].

Neonatal parameters included: birth weight and length, head circumference, gender, Apgar scores ≤ 7 in the first and in the fifth minute after birth and the rate of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

2.4. Study intervention

This study randomized volunteers in the interventional and control arm. Women participating in the control arm of the study had routine prenatal care according to local guidelines and health insurance requirements. Within the intervention group, yoga was practiced once a week, under the supervision of an internationally licensed and experienced prenatal yoga teacher. The teacher was certified to perform exercises according to the “Yoga in daily life” program which originated from Hatha Yoga [

6]. The adaptation of yoga practice for specific gestation age was based on in-depth consultation with gynaecologists and experienced physical therapists. The exercise plan protocol was strictly prescribed. The duration of one yoga exercise was 90 minutes. The exercises started in the 14th week of pregnancy and continued until delivery. Each pregnant woman completed 12 exercises.

Prenatal yoga was built through the following elements: i) deep relaxation, ii) yoga postures, iii) breathing exercises and iv) meditation. At the beginning of yoga practice, attendees performed an initial relaxation lasting 7–10 minutes, while lying on their left side, followed by yoga postures and stretching exercises and final 20–30 minutes of breathing and meditation techniques. A shorter relaxation lasting 2–3 minutes was performed in between the yoga postures and at the beginning of meditation. The selected yoga postures aim to strengthen the muscles of the body, especially the muscles of the pelvic floor. The meditation exercises included visualization, a technique that visually and sonically supports the emotional bonding of mother and child. Pregnant women were asked to visualize the foetus in the womb, the umbilical cord and the placenta. The yoga teacher guided them in visualizing the blood flow from their body to the placenta, passing through the umbilical cord, carrying nutrients and positive emotions to their child.

2.5. Statistics

Data gathered during the study were transferred to an electronic database, and the IBM SPSS Statistics version 28 was used for analysis. To ensure an adequate sample size to confirm statistical significance, we performed a power analysis, which showed that the smallest sample was 210 patients, 105 in each analysed group.

Numerical variables were first assessed for normality distribution using visualization and tests of normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests). Descriptive measures included proportions, the median with the first and third quartile range, and the mean with standard deviation. Categorical variables were assessed using the χ2-test and Fisher’s Exact test. Numerical continuous variables with normal distribution were analysed via a parametric Independent-samples T-test. Numerical variables that didn’t meet parametric assumptions as well as ordinal variables were analysed via the Mann-Whitney U test. A p < 0.05. was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

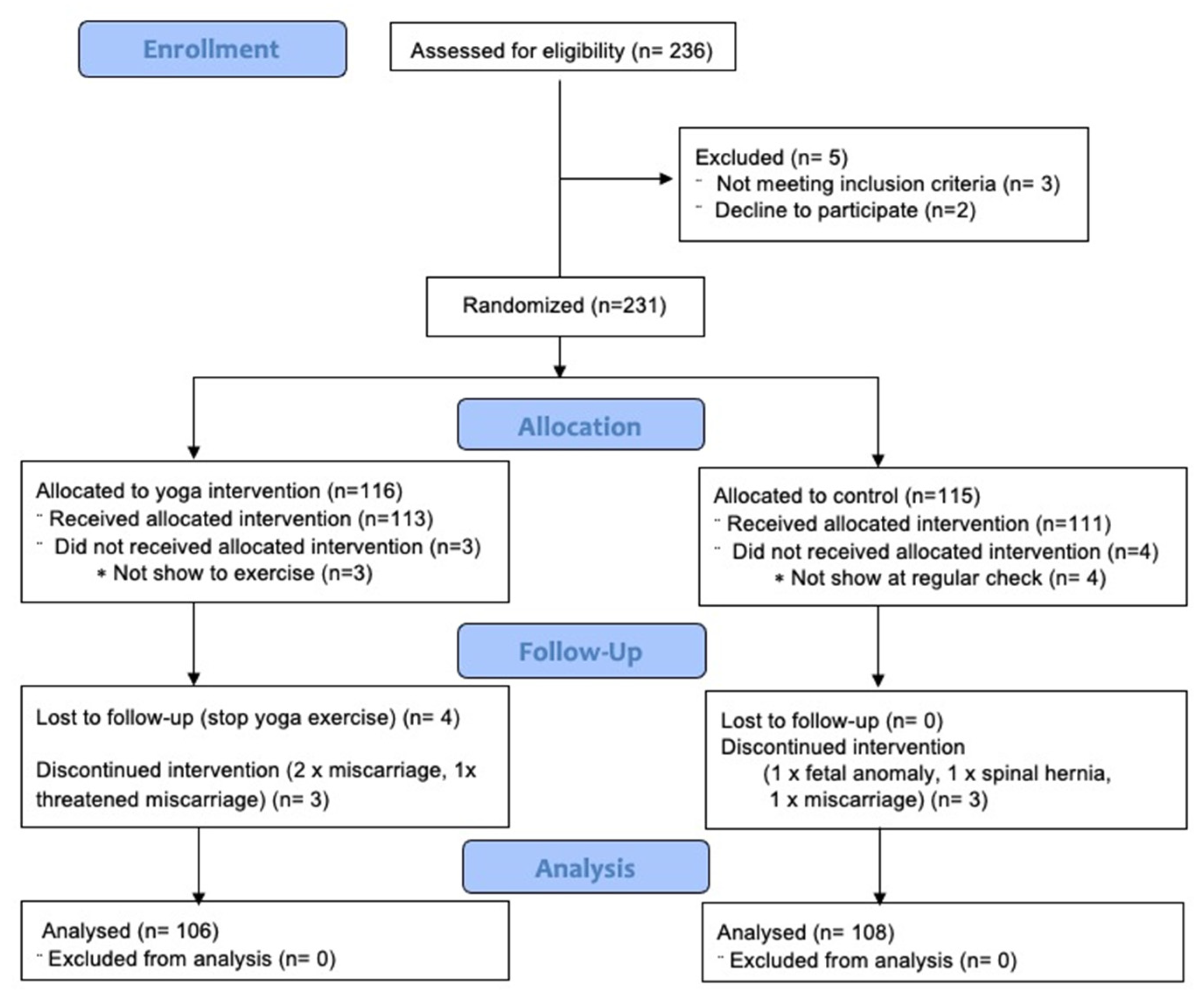

Participants were recruited during the first trimester of pregnancy. A total of 236 pregnant women were recruited between May 2019 and September 2023. Before randomization, we excluded 5 women: 3 for not meeting inclusion criteria, and 2 declined to participate. 231 participants were randomized; from all randomized women, 214 (92%) completed the study (

Figure 1). 116 were allocated to Yoga practice and 115 to Controls. 4 women randomized for Yoga failed to complete all 12 prescribed Yoga exercises and were excluded. Among the Control group, 4 pregnant women failed to show up for regular check and were excluded from the study. In follow-up, we lost 7 women from the yoga group: 4 discontinued yoga practice, 2 had a miscarriage and 1 had a threatened miscarriage. Among the control group, 3 discontinued the intervention: 1 terminated her pregnancy due to a foetal heart anomaly, 1 developed a spine hernia disc during pregnancy, and 1 had a miscarriage. For the final analysis, we have 106 pregnant women in the yoga group and 108 in the control group. The research plan, number of analysed pregnant women and primary outcomes are presented in

Figure 1. The flowchart of the study is shown in

Figure 2.

According to the

Table 1, the mean age of the participants in the study group was 29.6 ± 3.9years, and in the control group was 28.4 ± 4.5years. The mean body mass index in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy was 22.8± 2.9 kg/m2 in the study group and 23.6 ± 3.4 kg/m

2 in the control group. Maternal age, height, and body mass index (BMI) were similar in both groups with no difference in weight gain during pregnancy. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of gestational age at the time of enrolment and body mass index at the beginning of the study. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of education level.

Pregnant women from the study group had significantly lower intrapartum urgent CS rates and were more likely to deliver spontaneously (p = 0.004). Participants from the study group had less pain at the end of the first stage of labour and had a lower rate of perineal rupture (

Table 2).

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in the

Table 1.

We found a higher labour induction rate (p-0.032) and a higher urgent intrapartum CS rate in the control group (p-0.004). Spontaneous vaginal delivery was significantly more frequent in the study group (p-0.009). There was no premature birth in the study group. Severe perineal rupture was low in both groups while small degree perineal rupture was more frequent in the control group (p-0.049) There was no difference in the length of birth within the groups. The mean length of birth in the study group was 312.47 ± 147.3 min while it was 292.8 ± 124.5 min in the control group. Seven cases of instrumental vaginal delivery were observed in the control group and six in the study group. (

Table 2)

We found a statistically significant difference in the mean pain intensity measured by VAS at the end of the latent phase of the first stage of labour when the cervix was 3-6 cm dilated (

p < 0.001). Pathological CTG was significantly more frequent in the control group (p-0.038). The use of oxytocin to increase uterine contractions during labour did not differ between the two groups (

Table 2).

A closer look into indications for urgent intrapartum CS delivery shows that women from the control group had emergency CS mostly due to dystocia in 60%, while Yoga-practising women had it less frequently in 37%, but the difference was not significant. There was no significant difference in CS done due to non-reassuring foetal status and breech delivery among groups and there was no difference in dilatation of the cervix at the time of CS (

Table 3). For testing the difference among a limited group size, we used the Fisher Exact test.

According to the

Table 4, six of the neonates in the study group and 11 of the neonates in the control group had a first-minute Apgar score <7, while the fifth-minute Apgar score <7 was found in 2 neonates in the control group and 3 in the study group, which is not statistically significant.

The NICU admission did not differ between the groups (p-0.164). The mean and standard deviation of the infant birth weight in the study and control groups were 3436 ± 391 and 3406 ± 402, respectively.

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to investigate the effectiveness and safety of yoga practice during pregnancy and how it affects the pregnancy outcome. Compared to the control group, we found that women practising yoga during pregnancy have a significantly lower intrapartum urgent CS rate and deliver spontaneously more often. Furthermore, we found no association between yoga exercise during pregnancy and the greater need for oxytocin to increase uterine contractions. The results showed that yoga had a positive effect on coping with the severity of labour pain and maternal satisfaction with childbirth and that yoga practice during pregnancy significantly influences the successful preparation of pregnant women for spontaneous vaginal delivery. Compared to the control group with regular antenatal care, pregnant women practising yoga had no premature delivery, had lower rates of induction of labour, had less pain during labour and had less often pathological intrapartum CTG. The study results demonstrated that most of the nulliparous women practising antenatal yoga had spontaneous term vaginal delivery, which consequently has a significant and beneficial impact, for both; mother and new-born, presenting antenatal yoga as a valuable non-clinical intervention to safely reduce the CS rate. Women practising prenatal yoga had reduced stress and anxiety, better sleep, relaxed muscles of the pelvic grid, and greater self-confidence. Because of all the above positive effects, supported by the results from our study, antenatal yoga seems to be an important non-clinical intervention for a favourable delivery outcome [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Our results are consistent with studies of authors from India and Iran where yoga is culturally closer than in Europe [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Rising concerns have been expressed due to the continuous increase in C-section rates worldwide [

22]. Primiparous women have a three times higher risk of having a CS than multiparous women [

23]. Chaillet and Dumont highlighted a significant reduction in CS rates in a meta-analysis of 10 included studies evaluating the effectiveness of different strategies on CS rate reduction [

24]. The CS rate has also been shown to depend on the healthcare facility where the delivery is conducted [

25]. Our study was done in Slovenia where we had a 21.7% caesarean delivery rate according to the latest available results from the year 2020 and we are among European countries with the lowest CS rate [

26]. We don’t conduct CS on maternal request and we are among European countries with the 2nd lowest neonatal mortality rate (0.7 on 1000 live birth delivery), and the rate is lowering, despite that fact, the CS rate has increased by 0.9% from 2015 to 2020 [

26,

27].

Anxiety present during childbirth is linked to a higher level of adrenaline in the blood, which also affects the heart rate of the foetus, reduces uterine contractility, prolongs the duration of the active phase of labour and, consequently, possibly lowers the Apgar index of the newly born child. The mechanisms of yoga influence the reduction of unfavourable complications and the outcome of childbirth through the reduction of anxiety have been described [

28,

29,

30]. Pain caused by uterine contractions during childbirth is a subjective experience that is experienced differently according to individual perception and is conditioned by psychosocial, cognitive and physiological factors [

31]. Yoga seems to have a significant impact on the psychological and physiological aspects of women’s nature—and by improving all these parameters, it enables easier childbirth.

Several theories have been presented on how yoga affects the body. The definition of deep pranayama breathing is the voluntary manipulation of the breath. Deliberate, slow and deep breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system mainly due to stretching of lung tissue and vagal nerves. This leads to the body’s response by reducing the heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen consumption and metabolic rate [

32,

33]. Pranayama breathing also increases neuroplasticity—the reorganization of nerve pathways as a compensatory response and thus contributes to better concentration and motor skills [

32]. Studies that analysed the impact of yoga on blood pressure, heart rate, cortisol levels, cytokine activity and/or the work of regions in the brain responsible for mood regulation suggest that regular yoga practice affects better regulation of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis [

32]. The positive effect of yoga on stress in healthy pregnant women was confirmed [

34,

35]. Stress reduction and better response of the autonomic system due to yoga relaxation techniques, reduce sympathetic tone and with that improve sympathicovagal balance [

32,

33]. Reduction of stress and healthier autonomic response are effects of yoga that enhance the plasticity of the autonomic nervous system by improving the system’s ability to quickly restore its basal state of relaxation after it has responded to a stressor [

35].

Studies have highlighted prenatal yoga as being an effective complementary therapy that improves the birth outcome, as it reduces the intensity of pain and improves stress, depression and duration of labour, helping women feel more in control and satisfied with their labour. At the same time, the authors have stated that the level of evidence has methodological challenges and there is still no clear evidence that yoga had an impact on caesarean birth or delivery [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

In contrast, studies promoting moderate-intensity physical activity during pregnancy are high quality [

36]. ACOG clearly state in its guidelines; that 150 min of physical activity divided throughout the week is recommended to healthy pregnant woman. Proven benefits of exercise during pregnancy include lower incidence of caesarean delivery, excessive gestation weight gain, gestation diabetes mellitus, gestation hypertensive disorders, preterm birth, lower birth weight and higher incidence of vaginal delivery [

37].

Our study determined that yoga practice during pregnancy has the same benefit as moderate intensity physical activity recommended by ACOG and that the presented positive effects of practising yoga during pregnancy deserve more promotion visibility as a useful antenatal activity with proven safety.

We found that practising yoga during pregnancy lowers the intrapartum urgent CS rate and increases the spontaneous delivery rate in healthy primiparas with no adverse outcome for mothers and babies. Our study detected that the yoga group experienced less pain at the end of the active phase of the first stage of labour, which is in line with the findings of other authors [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Besides physical benefits, pregnant women practising yoga additionally learned how to increase self-confidence, competence and empowerment. All these skills help them to stay calm and in control during labour [

15].

Yoga is an activity that’s easily adjustable and it’s a safe intervention in pregnancy and postpartum [

38].

With its proven efficacy, the results of our study show that prenatal yoga may be a beneficial option for pregnant women in the selection of alternative therapies with the potential to lower the CS rate and facilitate spontaneous delivery. So, it should be used as a strategy for effectively reducing the primary CS rate among healthy pregnant women.

A strength of this study is that the protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov and published with open access. The study has limitations. In an attempt to control multiple variables related to caesarean delivery, we strictly selected the groups, so generalization on a broader population of pregnant women needs to be further examined. According to our results, prenatal yoga exercise can lead to a lower percentage of primary C-sections. It’s highly suggested to do more investigation on the effects of yoga exercises on different pregnancy consequences and delivery procedures, along with the samples of this study.

5. Conclusions

Yoga practice in pregnancy is a promising intervention that has the potential to decrease intrapartum urgent CS rates and assures natural and spontaneous vaginal birth and should be introduced and recommended to healthy pregnant women. The results of our study determined that yoga improves the labour process, increasing maternal satisfaction and positively affecting the outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth without causing complications for the mother and baby.

Our results may be used to support more researchers for extended collaborative work with licensed yoga teachers to standardize prenatal yoga interventions and conduct more robust evidence-based evaluations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.K., V.E.G., I.V.D., I.T., D.D. and F.M.; methodology, L.K., V.E.G., F.M., I.V.D. and D.D; software, L.K.; validation, V.E.G., I.T. and D.D.; formal analysis, D.D.; investigation, L.K.; resources and project administration, L.K.; data curation, L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, L.K.; writing—review and editing, V.E.G. and L.K.; supervision, V.E.G., F.M. and I.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was founded by University Medical Centre Maribor, grant number IRP-2018/01-03.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by University Medical Centre Maribor’s, Medical Ethic Committee; Number: UKC-MB-KME-29/17, date of approval 10 November 2017.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all pregnant women involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all pregnant women participating in this study and supporting us with their time spent at yoga and regular checks. We thank all the doctors who sent us participants and the team of the Perinatology department at the Maribor University Medical Centre. We are grateful to: midwife Melita Špoljar, Maša Brumec MD, Bernarda Unger and Alenka Ferk for all technical and administrative support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Babbar, S.; Shyken, J. Yoga in Pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2016, 5, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, L.; Moran, P.; Mc Grath, N.; Eustace-Cook, J.; Daly, D. The characteristics and effectiveness of pregnancy yoga interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, L.; Dai, L.J.; Ouyang, Y.Q. The effectiveness of prenatal yoga on delivery outcomes: A meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2020, 39, 101157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, CA; Levett, K.M.; Collins, C.T.; Armour, M; Dahlen, HG; Suganuma, M. Relaxation techniques for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 3, CD009514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, I.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Chou, S.H.; Shih, C.L. Efficacy of Prenatal Yoga in the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwarananda, S.P. The System Yoga in Daily Life Harmony for Body, Mind and Soul. Ibera Verlag/European University Press, 2000. Available online: https://www.yogaindailylife.org/system/en/ (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- ACOG Committee Opinion, No. 766: Approaches to Limit Intervention During Labor and Birth. Obstet Gynecol 2019, 133, 164–173. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulgu, M.M.; Birinci, S.; Altun Ensari, T.; Gözükara, M.G. Caesarean section rates in Turkey 2018-2023: Overview of national data by using Robson ten group classification system. Turk J Obstet Gynecol 2023, 20, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betran, A.P.; Ye, J.; Moller, A.B.; Souza, J.P.; Zhang, J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021, 6, e005671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Zhang, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Torloni, M.R.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Betran, A.P. Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century: a worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG 2016, 123, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh Gargari, S.; Essén, B.; Fallahian, M.; Mulic-Lutvica, A.; Mohammadi, S. Auditing the appropriateness of cesarean delivery using the Robson classification among women experiencing a maternal near miss. Int J Gynaecol Obstet, 2019, 144, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Statement on Cesarean Section Rates. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/who-statement-on-caesarean-section-rates-frequently-asked-questions (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Molina, G.; Weiser, T.G.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Esquivel, M.M.; Uribe-Leitz, T.; Azad, T.; Shah, N.; Semrau, K.; Berry, W.R.; Gawande, A.A.; Haynes, A.B. Relationship Between Caesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal Mortality. JAMA 2015, 2015 Dec 21, 2263–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO.WHO recommendations: Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Campbell, V.; Nolan, M. ‘It definitely made a difference’: A grounded theory study of yoga for pregnancy and women’s self-efficacy for labor. Midwifery, 2019, 68, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuntharapat, S.; Petpichetchian, W.; Hatthakit, U. Yoga during pregnancy: effects on maternal comfort, labor pain and birth outcomes. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2008, 14, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahdi, F.; Sheikhan, F.; Haghani, H.; Sharifi, B.; Ghaseminejad, A.; Khodarahmian, M.; Rouhana, N. Yoga during pregnancy: The effects on labor pain and delivery outcomes (A randomized controlled trial). Complement Ther Clin Pract 2017, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolanthakodi, C.; Raghunandan, C.; Saili, A.; Mondal, S.; Saxena, P. Prenatal Yoga: Effects on Alleviation of Labor Pain and Birth Outcomes. J Altern Complement Med 2018, 24, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyadin, E.; Ghorashi, Z.; Molamomanaei, Z. The effect of practicing yoga during pregnancy on labor stages length, anxiety and pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Complement Integr Med 2020, 18, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekefallah, L.; Namdar, P.; Dehghankar, L.; Golestaneh, F.; Taheri, S.; Mohammadkhaniha, F. The effect of yoga on the delivery and neonatal outcomes in nulliparous pregnant women in Iran: a clinical trial study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayres-de-Campos, D.; Spong, C.Y.; Chandraharan, E.; FIGO Intrapartum Fetal Monitoring Expert Consensus Panel. FIGO consensus guidelines on intrapartum fetal monitoring: Cardiotocography. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015, 131, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betrán, A.P.; Ye, J.; Moller, A.B.; Zhang, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Torloni, M.R. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0148343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, L.; Dundas, R.; Leyland, A.H. The influence of both individual and area—based socioeconomic status on temporal trends in caesarean sections in Scotland 1980–2000. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaillet, N.; Dumont, A. Evidence-based strategies for reducing cesarean section rates: a meta-analysis. Birth Berkeley Calif 2007, 34, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, B.B.; Amini, S.B.; Kappeler, K. Exercise in pregnancy: Effect on fitness and obstetric outcomes—A randomized trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exer 2012, 44, 2263–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdravstveni statistični letopis Slovenije 2021. Zdravstveno stanje prebivalstva 2. Available online: https://nijz.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2.2_Porodi_in_rojstva_2021_koncna_1.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Združenje za perinatalno medicino Slovenije. Poročilo EURO-PERISTAT. Available online: https://perinatologija.si/2290/ (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Hodnett, ED.; Gates, S.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C.; Weston, J. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011, 2, CD003766. [Google Scholar]

- Satyapriya, M.; Nagarathna, R.; Padmalatha, V.; Nagendra, H.R. Effect of integrated yoga on anxiety, depression & wellbeing in normal pregnancy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013, 4, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Newham, J.J.; Wittkowski, A.; Hurley, J.; Aplin, J.D.; Westwood, M. Effects of antenatal yoga on maternal anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, N.K. The nature of labor pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerath, R.; Edry, J.W.; Barnes, V.A.; Jerath, V. Physiology of long pranayamic breathing: neural respiratory elements may provide a mechanism that explains how slow deep breathing shifts the autonomic nervous system. Med Hypotheses 2006, 67, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žebeljan, I.; Lučovnik, M.; Dinevski, D.; Lackner, H.K.; Moertl, M.G.; Vesenjak Dinevski, I.; Mujezinović, F. Effect of Prenatal Yoga on Heart Rate Variability and Cardio-Respiratory Synchronization: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 5777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Bauer, I.E. A systematic review of randomised control trials on the effect of yoga on stress mesures and mood. J Psychiatr Res 2015, 68, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyapriya, M.; Nagendra, H.R; Nagarathna, R.; Padmalatha, V. Effect of integrated yoga on stress and heart rate variability in pregnant women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009, 104, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, D.; Magro-Malosso, E.R.; Saccone, G.; Marhefka, G.D.; Berghella, V. Exercise during pregnancy in normal-weight women and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016, 5, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 804. Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 4, e178–e188.

- Oyarzabal, E.A.; Seuferling, B.; Babbar, S.; Lawton-O’Boyle, S.; Babbar, S. Mind-Body Techniques in Pregnancy and Postpartum. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2021, 64, 683–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).