Submitted:

08 November 2023

Posted:

08 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

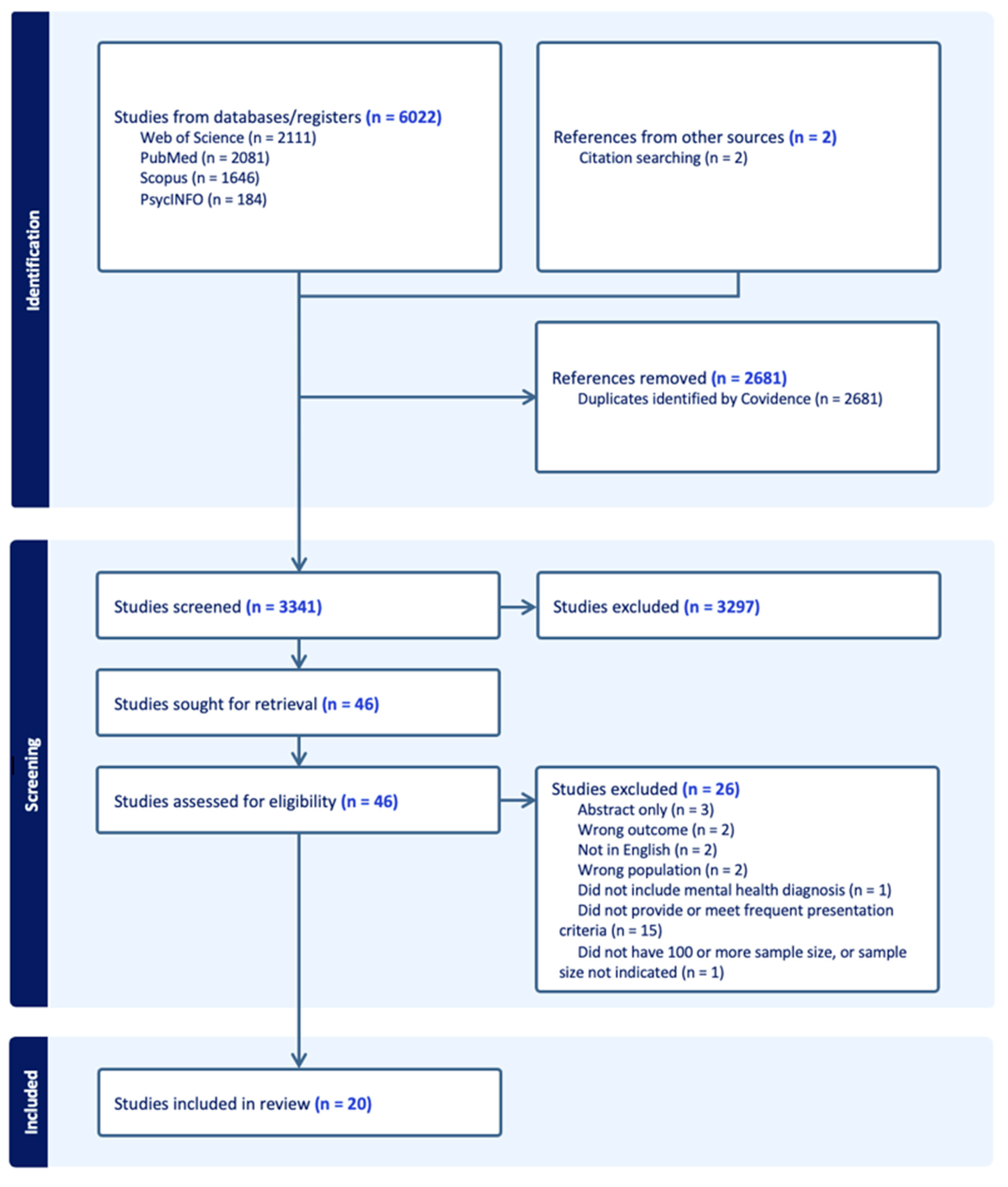

2. METHOD

- -

- were original studies that analysed aspects of trends, patterns, and characteristics of frequent presentations to ED with mental health diagnosis

- -

- defined ‘frequent presentation’ as 3 or more ED visits annually or equivalent

- -

- were published between Jan 2000 and April 2023 (23 years approximately)

- -

- were in English.

- -

- were on paediatric population

- -

- were based in military or non-civilian hospital

- -

- were reviews or editorials

- -

- were not peer-reviewed

- -

- did not have full text available

- -

- limited the scope of psychiatric conditions

3. RESULTS

- Sample size and FP definition

- Social profile

- Clinical profile

| Primary author | Publication year | Country | Diagnostic criteria |

FP number as % of total ED visitor number vs number of visits made by FP as % of total visits | FP definition | Sample FP size | FP Admission Rate | Socio-demographic characteristics n(%) | Top 3 Diagnosis: Category(%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | Employment status | Marriage status | Homelessness | Education level | Substance abuse history* | ||||||||||||||

| Male | Female | Others | <20 | 20-40 | 41-60 | 60+ | Employed | Married | Yes | Above secondary | Yes | |||||||||

| Arfken[12] | 2004 | US | NA | NA | ≥ 6v/yr | 74 | 30% | 74% | 26% | NA | Mean 40.6 | NA | NA | 60% | NA | 35% | 2(70%), 8(35%) | |||

| Pasic[18] | 2005 | US | ICD-10 | 4.4% vs NA | ≥ 4v/qr | 204 | NA | 74% | 26% | NA | Mean 36.9 | 45% | NA | 78% | NA | 34% | 8(22%), 2(15%), 4&5(15%) | |||

| Ledoux[19] | 2005 | Belgium | DSM-IV | NA | ≥ 4v/16m | 100 | NA | 70% | 30% | NA | Mean 33.6 | 19% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Brunero[20] | 2007 | Australia | ICD-9 | 1.5% vs 5.6% | ≥ 4v/yr | 13 | 46% | 62% | 38% | NA | 8% | 62% | 30% | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4&5(39%), 2(15%) |

| Mean 33 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mehl-Madrona[11] | 2008 | US | DSM-III-R | NA | ≥ 6v/yr | 200 | NA | 41% | 59% | NA | 18% | 34% | 21% | 27% | NA | NA | NA | NA | 31% | 4(24%), 8(19%), 5(16%) |

| Wooden[21] | 2009 | Australia | ICD-10 | 0.47% vs 4.5% | ≥ 1v/m | 54 | NA | NA | Mean 42.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9(33%), 2(25%), 4&5(23%) | |||||

| Vandyk[22] | 2014 | Canada | NA | 0.1% vs 3% | ≥ 5v/yr | 70 | NA | 66% | 34% | NA | 60% | 34% | 6% | 19% | 9% | 24% | NA | 67% | 2(30%), 3(20%), 8(20%) | |

| Brennan[23] | 2014 | US | ICD-9 | 3.3% vs 8.5% | ≥ 4v/yr | 2394 | NA | 57% | 43% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 26% | 2(56%), 3(54%), 5(48%) | |||

| Chang[24] | 2014 | US | NA | NA | ≥ 4v/yr & ≥ 3v/2m | 167 | NA | 56% | 44% | NA | 37% | 53% | 11% | NA | 31% | 23% | NA | 53% | 3(69%), 8(46%), 5(23%) | |

| Vu[25] | 2015 | Switzerland | NA | 0.9% vs NA | ≥ 5v/yr | 220 | NA | 55% | 45% | NA | Mean 51.5 | 54% | NA | NA | 19% | 61% | 8(61%), 4(47%), 5(34%) | |||

| Richard-Lepouriel[26] | 2015 | Switzerland | DSM-IV | NA | ≥ 3v/yr | 210 | NA | 49% | 51% | NA | Mean 38.7 | 16% | 25% | NA | NA | 52% | 8(52%), 3(49%), 9(40%) | |||

| Sirotich[27] | 2015 | Canada | NA | NA | ≥ 2v/6m | 146 | NA | 43% | 57% | NA | Mean 42.1 | 18% | NA | 18% | NA | 29% | 3(52%), 2(30%), 8(39%) | |||

| Buhumaid[28] | 2015 | US | DSM-IV | 0.27% vs 2.0% | ≥ 4v/yr | 126 | 22% | 64% | 36% | NA | 33% | 67% | NA | NA | 37% | NA | 81% | 2(63%), 4(42%), 3(15%) | ||

| Mean 43.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Meng[29] | 2017 | Canada | ICD-10 | NA | ≥ 10v/yr | 34 | NA | 65% | 35% | NA | Mean 40 | 15% | NA | 50% | 21% | 65% | 8(53%), 5(26%), 4(12%) | |||

| Fleury[14] | 2019 | Canada | ICD-9/10 | NA | ≥ 3v/yr | 10969 | NA | 53% | 47% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 46% | 5(50%), 4(45%), 2(34%) | |||

| Slankamenac[30] | 2020 | Switzerland | NA | NA | ≥ 4v/yr | 45 | NA | 62% | 38% | NA | Mean 42.7 | 13% | 28% | 16% | 47% | 36% | 8(44%), 9(22%), 2(11%) | |||

| Casey[31] | 2021 | Australia | ICD-10 | NA | ≥ 4v/yr | 200 | NA | 53% | 46.5% | 0.5% | 13% | 58% | 28% | 2% | 6% | 6% | NA | 7% | NA | 9(15%), 2(14%), 3(9%) |

| Mean 33.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Gentil[15] | 2021 | Canada | ICD-9/10 | NA | ≥ 3v/yr | 3121 | NA | 54% | 46% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 41% | 5(56%), 7(43%), 4(48%) | |||

| Armoon[16] | 2022 | Canada | ICD-9/10 | NA | ≥ 3v/yr | 5510 | NA | 47% | 53% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 48% | 4&5(85%), 2&3(57%) | |||

| Cullen[32] | 2022 | Australia | ICD-10 | NA | ≥ 4v/yr | 1831 | 41% | 43% | 57% | NA | Range 8-26 only | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5(15%), 4(9%) | |||

| Combined Data: calculated with corresponding available data only | 25688 | 26% | 52% | 48% | NA | 15% | 47% | 25% | 13% | 27% | 20% | 41% | 17% | 44% | 5(44%), 4(39%), 2(33%) | |||||

| 52% | 48% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mean 40.7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

4. DISCUSSION

- Profiles of FPs

- Socio-demographic characteristics

- Clinical characteristics

- Influence on care

- Suggestions

- Limitations and implications on future research

5. CONCLUSION

STATEMENT FOR COMPETING INTERESTS AND FUNDING

References

- Emergency department care activity. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/myhospitals/intersection/activity/ed#:~:text=In%202021–22%3A,were%20Admitted%20to%20this%20hospital (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Mental health services provided in emergency departments. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/mental-health/topic-areas/emergency-departments (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Shehada, E.R.; He, L.; Eikey, E.V.; Jen, M.; Wong, A.; Young, S.D.; Zheng, K. Characterizing Frequent Flyers of an Emergency Department Using Cluster Analysis. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019, 264, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaCalle, E.; Rabin, E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med 2010, 56, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slankamenac, K.; Zehnder, M.; Langner, T.O.; Krähenmann, K.; Keller, D.I. Recurrent Emergency Department Users: Two Categories with Different Risk Profiles. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chastonay, O.J.; Lemoine, M.; Grazioli, V.S.; Canepa Allen, M.; Kasztura, M.; Moullin, J.C.; Daeppen, J.B.; Hugli, O.; Bodenmann, P. Health care providers' perception of the frequent emergency department user issue and of targeted case management interventions: a cross-sectional national survey in Switzerland. BMC Emerg Med 2021, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judkins, S.; Fatovich, D.; Ballenden, N.; Maher, H. Mental health patients in emergency departments are suffering: the national failure and shame of the current system. A report on the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine's Mental Health in the Emergency Department Summit. Australas Psychiatry 2019, 27, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. , et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Medicine 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, S.L.; Polihronis, C.; Cloutier, P.; Zemek, R.; Newton, A.S.; Gray, C.; Cappelli, M. Family Factors and Repeat Pediatric Emergency Department Visits for Mental Health: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019, 28, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lung, N.H.; institute, B. Study Quality Assessment Tools| NHLBI, NIH. Retrieved from Study Quality Assessment Tools website2021. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- Mehl-Madrona, L.E. Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses among frequent users of rural emergency medical services. Can J Rural Med 2008, 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Arfken, C.L.; Zeman, L.L.; Yeager, L.; White, A.; Mischel, E.; Amirsadri, A. Case-Control Study of Frequent Visitors to an Urban Psychiatric Emergency Service. Psychiatr. Serv. 2004, 55, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locker, T.E.; Baston, S.; Mason, S.M.; Nicholl, J. Defining frequent use of an urban emergency department. Emerg Med J 2007, 24, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, M.J.; Rochette, L.; Grenier, G.; Huynh, C.; Vasiliadis, H.M.; Pelletier, E.; Lesage, A. Factors associated with emergency department use for mental health reasons among low, moderate and high users. GENERAL HOSPITAL PSYCHIATRY 2019, 60, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentil, L.; Grenier, G.; Vasiliadis, H.M.; Huynh, C.; Fleury, M.J. Predictors of Recurrent High Emergency Department Use among Patients with Mental Disorders. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND PUBLIC HEALTH 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armoon, B.; Cao, Z.R.; Grenier, G.; Meng, X.F.; Fleury, M.J. Profiles of high emergency department users with mental disorders. AMERICAN JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE 2022, 54, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, 2013.

- Pasic, J.; Russo, J.; Roy-Byrne, P. High utilizers of psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv 2005, 56, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledoux, Y.; Minner, P. Occasional and frequent repeaters in a psychiatric emergency room. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006, 41, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunero, S.; Fairbrother, G.; Lee, S.; Davis, M. Clinical characteristics of people with mental health problems who frequently attend an Australian emergency department. Aust Health Rev 2007, 31, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wooden, M.D.; Air, T.M.; Schrader, G.D.; Wieland, B.; Goldney, R.D. Frequent attenders with mental disorders at a general hospital emergency department. Emerg Med Australas 2009, 21, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandyk, A.D.; VanDenKerkhof, E.G.; Graham, I.D.; Harrison, M.B. Profiling Frequent Presenters to the Emergency Department for Mental Health Complaints: Socio-Demographic, Clinical, and Service Use Characteristics. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2014, 28, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, J.J.; Chan, T.C.; Hsia, R.Y.; Wilson, M.P.; Castillo, E.M. Emergency department utilization among frequent users with psychiatric visits. Acad Emerg Med 2014, 21, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, G.; Weiss, A.P.; Orav, E.J.; Rauch, S.L. Predictors of frequent emergency department use among patients with psychiatric illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014, 36, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, F.; Daeppen, J.B.; Hugli, O.; Iglesias, K.; Stucki, S.; Paroz, S.; Canepa Allen, M.; Bodenmann, P. Screening of mental health and substance users in frequent users of a general Swiss emergency department. BMC Emerg Med 2015, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard-Lepouriel, H.; Weber, K.; Baertschi, M.; DiGiorgio, S.; Sarasin, F.; Canuto, A. Predictors of recurrent use of psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv 2015, 66, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirotich, F.; Durbin, A.; Durbin, J. Examining the need profiles of patients with multiple emergency department visits for mental health reasons: a cross-sectional study. SOCIAL PSYCHIATRY AND PSYCHIATRIC EPIDEMIOLOGY 2016, 51, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhumaid, R.; Riley, J.; Sattarian, M.; Bregman, B.; Blanchard, J. Characteristics of Frequent Users of the Emergency Department with Psychiatric Conditions. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2015, 26, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Muggli, T.; Baetz, M.; D'Arcy, C. Disordered lives: Life circumstances and clinical characteristics of very frequent users of emergency departments for primary mental health complaints. Psychiatry Res 2017, 252, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slankamenac, K.; Heidelberger, R.; Keller, D.I. Prediction of Recurrent Emergency Department Visits in Patients With Mental Disorders. FRONTIERS IN PSYCHIATRY 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, M.; Perera, D.; Enticott, J.; Vo, H.; Cubra, S.; Gravell, A.; Waerea, M.; Habib, G. High utilisers of emergency departments: the profile and journey of patients with mental health issues. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2021, 25, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, P.; Leong, R.N.; Liu, B.; Walker, N.; Steinbeck, K.; Ivers, R.; Dinh, M. Returning to the emergency department: a retrospective analysis of mental health re-presentations among young people in New South Wales, Australia. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, A.; Van de Velde, S.; Vilagut, G.; de Graaf, R.; O'Neill, S.; Florescu, S.; Alonso, J.; Kovess-Masfety, V. Gender differences in mental disorders and suicidality in Europe: results from a large cross-sectional population-based study. J Affect Disord 2015, 173, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Conditions Prevalence. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/health-conditions-prevalence/2020-21 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Chatmon, B.N. Males and Mental Health Stigma. Am J Mens Health 2020, 14, 1557988320949322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.C.; Hammer, J.H.; Bradstreet, T.C.; Schwartz, E.N.; Jobe, T. Men's Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviors: An Intersectional Analysis. Am J Mens Health 2018, 12, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, F.; Antonio, M.; Davison, K.; Queen, R.; Devor, A. A rapid review of gender, sex, and sexual orientation documentation in electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020, 27, 1774–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S.; Makadon, H. Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data Collection in Clinical Settings and in Electronic Health Records: A Key to Ending LGBT Health Disparities. LGBT Health 2014, 1, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Power, J.; Smith, E.; Rathbone, M. Bisexual mental health and gender diversity: Findings from the ‘Who I Am’ study. Australian Journal for General Practitioners 2020, 49, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Suka, M.; Yanagisawa, H. Help-Seeking Behavior and Psychological Distress by Age in a Nationally Representative Sample of Japanese Employees. J Epidemiol 2020, 30, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorem, G.F.; Schirmer, H.; Wang, C.E.A.; Emaus, N. Ageing and mental health: changes in self-reported health due to physical illness and mental health status with consecutive cross-sectional analyses. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, G.; den Daas, C.; Johnston, M.; Dixon, D. Sociodemographic and Psychological Risk Factors for Anxiety and Depression: Findings from the Covid-19 Health and Adherence Research in Scotland on Mental Health (CHARIS-MH) Cross-sectional Survey. Int J Behav Med 2021, 28, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, M.-J.; Grenier, G.; Bamvita, J.-M.; Perreault, M.; Jean, C. Typology of adults diagnosed with mental disorders based on socio-demographics and clinical and service use characteristics. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Sick on the Job?; 2012; [CrossRef]

- Junna, L.; Moustgaard, H.; Martikainen, P. Current Unemployment, Unemployment History, and Mental Health: A Fixed-Effects Model Approach. Am J Epidemiol 2022, 191, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, L.; Fasani, F.; Mueller, H. Feeling useless: the effect of unemployment on mental health in the Great Recession. IZA Journal of Labor Economics 2018, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, K.; Watson, N. Unemployment and mental health. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 1995, 2, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartelink, V.H.M.; Zay Ya, K.; Guldbrandsson, K.; Bremberg, S. Unemployment among young people and mental health: A systematic review. Scand J Public Health 2020, 48, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIHW media releases. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/news-media/media-releases/2002/oct/financial-difficulty-most-common-reason-for-homele (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Ryu, S.; Fan, L. The Relationship Between Financial Worries and Psychological Distress Among U.S. Adults. J Fam Econ Issues 2023, 44, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. OECD Affordable Housing Database. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/housing/data/affordable-housing-database/ (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Johnson, G.; Chamberlain, C. Are the Homeless Mentally Ill? Australian Journal of Social Issues 2011, 46, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Population with tertiary education. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/population-with-tertiary-education.htm (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Niemeyer, H.; Bieda, A.; Michalak, J.; Schneider, S.; Margraf, J. Education and mental health: Do psychosocial resources matter? SSM Popul Health 2019, 7, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, R.; Parker, K. Rising Share of U.S. Adults Are Living Without a Spouse or Partner. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2021/10/05/rising-share-of-u-s-adults-are-living-without-a-spouse-or-partner/#fnref-31655-3 (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Jace, C.E.; Makridis, C.A. Does marriage protect mental health? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Science Quarterly 2021, 102, 2499–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Takeuchi, D.; Adair, R. Marital Status and Psychiatric Disorders Among Blacks and Whites. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 1992, 33, 140–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.L.; Kail, B.L. Socioeconomic variation in the association of marriage with depressive symptoms. Social Science Research 2018, 71, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynek, K.A.; Abebe, D.S.; Liefbroer, A.C.; Hauge, L.J.; Straiton, M.L. The association between early marriage and mental disorder among young migrant and non-migrant women: a Norwegian register-based study. BMC Women's Health 2022, 22, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Hany, M.; Rehman, B.; Azhar, Y.; Chapman, J. Schizophrenia. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing.

- Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Baryiah Rehman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Yusra Azhar declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Jennifer Chapman declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies., 2023.

- Conley, R.R.; Ascher-Svanum, H.; Zhu, B.; Faries, D.E.; Kinon, B.J. The burden of depressive symptoms in the long-term treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2007, 90, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temmingh, H.; Stein, D.J. Anxiety in Patients with Schizophrenia: Epidemiology and Management. CNS Drugs 2015, 29, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, G.S.; Isaac, M.K. Models of Care of Schizophrenia in the Community-An International Perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2022, 24, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, E. Rates of use of community treatment orders in Australia. Int J Law Psychiatry 2019, 64, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, L.B.; Dickerson, F.; Bellack, A.S.; Bennett, M.; Dickinson, D.; Goldberg, R.W.; Lehman, A.; Tenhula, W.N.; Calmes, C.; Pasillas, R.M.; et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull 2010, 36, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballou, S.; Mitsuhashi, S.; Sankin, L.S.; Petersen, T.S.; Zubiago, J.; Lembo, C.; Takazawa, E.; Katon, J.; Sommers, T.; Hirsch, W.; et al. Emergency department visits for depression in the United States from 2006 to 2014. General Hospital Psychiatry 2019, 59, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarthy, B.; Toohey, S.; Rezaimehr, Y.; Anderson, C.L.; Hoonpongsimanont, W.; Menchine, M.; Lotfipour, S. National differences between ED and ambulatory visits for suicidal ideation and attempts and depression. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2014, 32, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiser, D.G.; Ward, C.E.; Vu, M.; Laiteerapong, N.; Gibbons, R.D. Depression in Emergency Department Patients and Association With Health Care Utilization. Academic Emergency Medicine 2019, 26, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, B.; Lickel, J.; Abramowitz, J.S. Medical utilization across the anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2008, 22, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Kimura, T.; Inagaki, Y.; Shirakawa, O. Prevalence of Comorbid Anxiety Disorders and Their Associated Factors in Patients with Bipolar Disorder or Major Depressive Disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2020, 16, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapici Eser, H.; Kacar, A.S.; Kilciksiz, C.M.; Yalçinay-Inan, M.; Ongur, D. Prevalence and Associated Features of Anxiety Disorder Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Study. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, J.C.; Córcoles, D.; Castaño, J.; Ginés, J.M.; Gurrea, A.; Martín-Santos, R.; Garcia-Ribera, C.; Pérez, V.; Bulbena, A. Hospitalization and Pharmacotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder in a Psychiatric Emergency Service. Psychiatric Services 2007, 58, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbear, J.H.; Rotella, J.A.; Lorenze, D.; Rao, S. Emergency department utilisation by patients with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder: An acute response to a chronic disorder. Emerg Med Australas 2022, 34, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisti, D.; Segal, A.G.; Siegel, A.M.; Johnson, R.; Gunderson, J. Diagnosing, Disclosing, and Documenting Borderline Personality Disorder: A Survey of Psychiatrists' Practices. J Pers Disord 2016, 30, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Drug Use. Our World in Data 2019.

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.P.; Burstein, M.; Swanson, S.A.; Avenevoli, S.; Cui, L.; Benjet, C.; Georgiades, K.; Swendsen, J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010, 49, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, R.E.F.; Marel, C.; Mills, K.L. A systematic review of the prevalence of comorbid mental health disorders in people presenting for substance use treatment in Australia. Drug Alcohol Rev 2017, 36, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, P.M.; Brown, B.S. Co-occurring disorders in substance abuse treatment: issues and prospects. J Subst Abuse Treat 2008, 34, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A.K.; Dai, Y.; Ross, J.S.; Schuur, J.D.; Capp, R.; Krumholz, H.M. Variation in US hospital emergency department admission rates by clinical condition. Med Care 2015, 53, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health system failing those with poor mental health. Available online: https://www.ama.com.au/media/health-system-failing-those-poor-mental-health (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Mautner, D.B.; Pang, H.; Brenner, J.C.; Shea, J.A.; Gross, K.S.; Frasso, R.; Cannuscio, C.C. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag 2013, 16 Suppl 1, S26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtakangas, M.; Tuomikoski, A.-M.; Kyngäs, H.; Kanste, O. Frequent attenders' experiences of encounters with healthcare personnel: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Nursing & Health Sciences 2021, 23, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, W.; Shalaby, R.; Agyapong, V.I.O. Interventions to Reduce Repeat Presentations to Hospital Emergency Departments for Mental Health Concerns: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, P.; Brandenburg, D.L.; Bremer, K.L.; Nordstrom, D.L. Effects of team care of frequent attenders on patients and physicians. Fam Syst Health 2010, 28, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altin, S.V.; Stock, S. The impact of health literacy, patient-centered communication and shared decision-making on patients' satisfaction with care received in German primary care practices. BMC Health Serv Res 2016, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, S.; von Hafe, F.; Martins, F.; Menino, C.; Guimarães, M.J.; Mesquita, A.; Sampaio, S.; Londral, A.R. Case management intervention of high users of the emergency department of a Portuguese hospital: a before-after design analysis. BMC Emergency Medicine 2022, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, T.; Koekkoek, B.; Hutschemaekers, G.; Tiemens, B. Potential predictive factors for successful referral from specialist mental-health services to less intensive treatment: A concept mapping study. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0199668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System Final Report; Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System: 2 March 2021, 2021.

| Platform | Search Strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | #1 | "Emergency Service, Hospital"[Mesh] OR ED OR hospital |

| #2 | "multiple presentation" OR "multiple attendance" OR "multiple visits" OR "repeated presentation" OR "repeated attendance" OR "repeated visits" OR "frequent presentation" OR "frequent presenter" OR "frequent attendance" OR "frequent representation" OR "frequent visitor" OR "frequent flyer" OR "frequent users" OR "recurrent presentation" OR "recurrent visits" OR "re-presentation" | |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | |

|

PsycINFO Scopus WOS |

#1 | "emergency department" OR ED OR "emergency care" OR hospital |

| #2 | "multiple presentation" OR "multiple attendance" OR "multiple visits" OR "repeated presentation" OR "repeated attendance" OR "repeated visits" OR "frequent presentation" OR "frequent presenter" OR "frequent attendance" OR "frequent representation" OR "frequent visitor" OR "frequent flyer" OR "frequent users" OR "recurrent presentation" OR "recurrent visits" OR "re-presentation" | |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).