Submitted:

13 November 2023

Posted:

13 November 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Sample Size

2.3. Data Collection and Instrument

- -

- Personal data (8 closed-ended questions): This section assessed social demographics (age, gender, profession, education level), employment status (type of hospital, years of work experience) and previous education or training in stroke along with the sources of such education.

- -

-

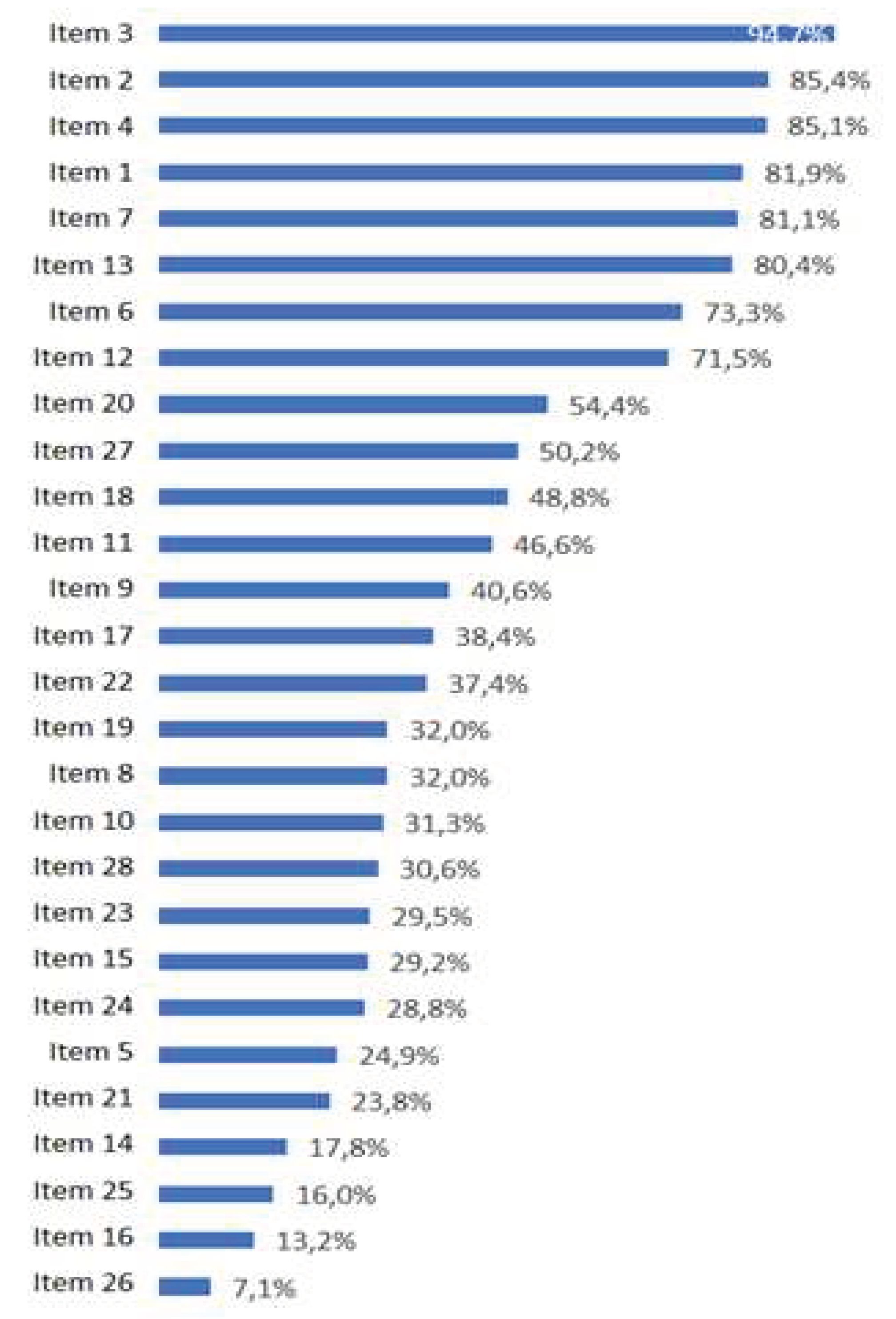

Knowledge on stroke recognition and management (28 questions). This section assessed:

- (a)

- General knowledge on stroke [Question regarding general knowledge on stroke (QGK)]: 4 questions with possible responses include ‘right’, ‘wrong’ or 'I don't know’

- (b)

- Knowledge on stroke recognition [Question regarding knowledge on stroke recognition (QKSR)]: 2 multiple choice questions and 6 questions with possible responses include ‘right’, ‘wrong’ or 'I don't know’

- (c)

- Knowledge on stroke management [Question regarding knowledge on stroke management (QKSM)]: 2 multiple choice questions and 14 questions with possible responses include ‘right’, ‘wrong’ or 'I don't know’]

- (d)

- Self assessment on knowledge on stroke recognition and management: 1 question with possible responses include 'poorly’, 'well’, 'very well’ and ‘expert’.

2.4. Questionnaire Development

2.4. Ethics Approval

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire Testing

3.2. Characteristics of the Srudy Participants

3.2 Stroke Knowledge Levels

3.3 Univariate and Multivariate Predictors of Stroke Knowledge

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, A.; Berdunov, V.; King, D.; Quayyum, Z.; Wittenberg, R.; Knapp, M. Current, Future and Avoidable Costs of Stroke in the UK, Executive Summary Part 2. Stroke Assoc. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, E139–E596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wafa, H.A.; Wolfe, C.D.A.; Emmett, E.; Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Wang, Y. Burden of Stroke in Europe: Thirty-Year Projections of Incidence, Prevalence, Deaths, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years. Stroke 2020, 51, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, A.H.; Churilov, L.; Mitchell, P.J.; Dowling, R.J.; Yan, B. Every 15-Min Delay in Recanalization by Intra-Arterial Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke Increases Risk of Poor Outcome. Int. J. Stroke 2015, 10, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; Biller, J.; Brown, M.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Hoh, B.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke; 2019; Vol. 50; ISBN 0000000000000.

- Jauch, E.C.; Saver, J.L.; Adams, H.P.; Bruno, A.; Connors, J.J.B.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Khatri, P.; McMullan, P.W.; Qureshi, A.I.; Rosenfield, K.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013, 44, 870–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, E364–E467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althubaity, E.; Yunus, F.; Khathaami, A. Al Assessment of the Experience of Saudi Emergency Medical Services Personnel with Acute Stroke. Neurosciences 2013, 18, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Munder, S.P.; Chaudhry, A.; Madan, R.; Gribko, M.; Arora, R. Emergency Medical Services Providers’ Knowledge, Practices, and Barriers to Stroke Management. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2019, 11, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibiasio, E.L.; Jayaraman, M. V.; Oliver, L.; Paolucci, G.; Clark, M.; Watkins, C.; Delisi, K.; Wilks, A.; Yaghi, S.; Hemendinger, M.; et al. Emergency Medical Systems Education May Improve Knowledge of Pre-Hospital Stroke Triage Protocols. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2020, 12, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shire, F.; Kasim, Z.; Alrukn, S.; Khan, M. Stroke Awareness among Dubai Emergency Medical Service Staff and Impact of an Educational Intervention. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorchs-Molist, M.; Solà-Muñoz, S.; Enjo-Perez, I.; Querol-Gil, M.; Carrera-Giraldo, D.; Nicolàs-Arfelis, J.M.; Jiménez-Fàbrega, F.X.; de la Ossa, N.P. An Online Training Intervention on Prehospital Stroke Codes in Catalonia to Improve the Knowledge, Pre-Notification Compliance and Time Performance of Emergency Medical Services Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sveikata, L.; Melaika, K.; Wiśniewski, A.; Vilionskis, A.; Petrikonis, K.; Stankevičius, E.; Jurjans, K.; Ekkert, A.; Jatužis, D.; Masiliūnas, R. Interactive Training of the Emergency Medical Services Improved Prehospital Stroke Recognition and Transport Time. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Ward, E.; John, S.; Lopes, D.K.; Chen, M.; Temes, R.E.; Mohammad, Y.; Lee, V.H.; Bleck, T.P. Transfer Delay Is a Major Factor Limiting the Use of Intra-Arterial Treatment in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2011, 42, 1626–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTaggart, R.A.; Ansari, S.A.; Goyal, M.; Abruzzo, T.A.; Albani, B.; Arthur, A.J.; Alexander, M.J.; Albuquerque, F.C.; Baxter, B.; Bulsara, K.R.; et al. Initial Hospital Management of Patients with Emergent Large Vessel Occlusion (ELVO): Report of the Standards and Guidelines Committee of the Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2017, 9, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, B.Y.G.; Ni, H.M.J.; Tiah, L.; Tan, C. The Challenge of Tightening Door-to-Needle Timings in a Telestroke Setting: An Emergency Medicine Driven Initiative. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.E.; McInnes, E.; Taylor, N.; Grimley, R.; Cadilhac, D.A.; Considine, J.; Middleton, S. Identifying the Barriers and Enablers for a Triage, Treatment, and Transfer Clinical Intervention to Manage Acute Stroke Patients in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review Using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baatiema, L.; Otim, M.; Mnatzaganian, G.; Aikins, A.D.G.; Coombes, J.; Somerset, S. Towards Best Practice in Acute Stroke Care in Ghana: A Survey of Hospital Services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruins Slot, K.; Murray, V.; Boysen, G.; Berge, E. Thrombolytic Treatment for Stroke in the Scandinavian Countries. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2009, 120, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurer, W.J.; Majersik, J.J.; Frederiksen, S.M.; Kade, A.M.; Sandretto, A.M.; Scott, P.A. Provider Perceptions of Barriers to the Emergency Use of TPA for Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Qualitative Study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2011, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, S.; Murano, T.; Nagurka, R. Emergency Department Healthcare Providers’ Knowledge of Ischemic Stroke. Res. Dev. Med. Educ. 2013, 2, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Jude, M.R.; Levi, C.R. Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator (Rt-PA) Utilisation by Rural Clinicians in Acute Ischaemic Stroke: A Survey of Barriers and Enablers. Aust. J. Rural Health 2013, 21, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecksén, A.; Lundman, B.; Eriksson, M.; Glader, E.L.; Asplund, K. Implementing Thrombolytic Guidelines in Stroke Care: Perceived Facilitators and Barriers. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, A.M.; Bryant, J.; Carey, M.L.; Paul, C.L.; Sanson-Fisher, R.W.; Levi, C.R. Agreement with Evidence for Tissue Plasminogen Activator Use among Emergency Physicians: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khathaami, A.M.; Aloraini, H.; Almudlej, S.; Al Issa, H.; Elshammaa, N.; Alsolamy, S. Knowledge and Attitudes of Saudi Emergency Physicians toward T-PA Use in Stroke. Neurol. Res. Int. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.; Alosaimi, M.; Aldawsari, R.M.; Alatwai, A.M.; Idris, M.A. Saudi Emergency Physicians ’ Knowledge about Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Acute Ischemic Stroke. 2019, 10, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, L.H.; Harrington, K.; Rogers, H.; Langhorne, P.; Smith, M.; Bond, S. Development of a Scale to Assess Nurses’ Knowledge of Stroke: A Pilot Study. Clin. Rehabil. 1999, 13, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.P. Emergency Nurses’ Knowledge of Evidence-Based Ischemic Stroke Care: A Pilot Study. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2007, 33, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynelis, L. Emergency Department Nurses’ Knowledge of Evidence-Based Ischemic Stroke Care. Kaleidoscope 2012, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Adelman, E.E.; Meurer, W.J.; Nance, D.K.; Kocan, M.J.; Maddox, K.E.; Morgenstern, L.B.; Skolarus, L.E. Stroke Awareness among Inpatient Nursing Staff at an Academic Medical Center. Stroke 2014, 45, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, S.S.; Murray, L.L.; Mclennon, S.M.; Bakas, T. Implementation of a Stroke Competency Program to Improve Nurses’ Knowledge of and Adherence to Stroke Guidelines. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2016, 48, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbampato dos Santos, J.V.; Aparecida de Melo, E.; Lopes da Silveira Junior, J.; Nascimento Vasconcelos, N.; de Castro Lima, M.; Moreira Damázio, L.C. The Effects of Nursing Training on the Evaluation of Patients With Cerebrovascular Accident. J. Nurs. UFPE / Rev. Enferm. UFPE 2017, 11, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, P.; Srijithesh, P.; Ashraf, J.; Kannan, D. Emergency Nurses’ Knowledge about Tissue Plasminogen Activator Therapy and Their Perception about Barriers for Thrombolysis in Acute Stroke Care. Int. J. Noncommunicable Dis. 2019, 4, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Vakani, R.; Kussin, P.; Guhwe, M.; Farjat, A.E.; Choudhury, K.; Renner, D.; Oduor, C.; Graffagnino, C. Assessment of Healthcare Personnel Knowledge of Stroke Care at a Large Referral Hospital in Sub-Saharan Africa – A Survey Based Approach. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 42, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E.; FAul, F.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauch, E.C.; Saver, J.L.; Adams, H.P.; Bruno, A.; Connors, J.J.B.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Khatri, P.; McMullan, P.W.; Qureshi, A.I.; Rosenfield, K.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association / American Stroke Association; 2018; Vol. 44; ISBN 9780309140942.

- Gnatzy, T.; Warth, J.; von der Gracht, H.; Darkow, I.L. Validating an Innovative Real-Time Delphi Approach - A Methodological Comparison between Real-Time and Conventional Delphi Studies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2011, 78, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Wright, C.C. The Kappa Statistic in Reliability Studies: Use, Interpretation, and Sample Size Requirements. Phys. Ther. 2005, 85, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L. Measurement in Medicine: A Practical Guide. Meas. Med. A Pract. Guid. 2011, 1–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albart, S.A.; Khan, A.H.K.Y.; Rashid, A.A.; Zaidi, W.A.W.; Bidin, M.Z.; Looi, I.; Hoo, F.K. Knowledge of Acute Stroke Management and the Predictors among Malaysian Healthcare Professionals. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Weng, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhao, J. Significant Stroke Knowledge Deficiencies in Community Physician Improved with Stroke 120. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blek, N.; Szarpak, L. Profile of Practices and Knowledge on Stroke among Polish Emergency Medical Service Staff. Disaster Emerg. Med. J. 2021, 6, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Kappa | Agreement percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Every patient presenting with an AIS should be treated as a medical emergency, whether eligible for thrombolysis or not (QGN) | 0.73 | 87% |

| 2. AIS represents a life-threatening situation (QGN) | 0.86 | 93% |

| 3. EDs play a vital role in the early recognition of AIS and the timely commencement of treatment (QGN) | 1.00 | 100% |

| 4. EMS personnel should inform ED about the transfer of a patient with probable AIS (QGN) | 0.33 | 73% |

| 5. NIHSS is the proposed scale for AIS severity assessment (QKSR) | 0.55 | 80% |

| 6. A patient presenting to the ED with AIS is most likely to experience which of the following symptoms? i) tremor, dizziness, vomiting; ii) altered level of consciousness, tachypnea, cyanosis; iii) unilateral arm or leg weakness or face drooping or difficulty speaking; (QKSR) | 0.47 | 80% |

| 7. Which of the following can mimic an AIS? i) Hypoglycemia, ii) hyperkalemia, iii) heat stroke, iv) pulmonary embolism (QKSR) | 0.59 | 87% |

| 8. Brain MRI is the recommended diagnostic modality to differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (QKSR) | 0.48 | 73% |

| 9. In a patient with suspected stroke, clinical examination and history taking can securely differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke (QKSR) | 0.21 | 67% |

| 10. 60 minutes is the maximum time allowed from the arrival of the patient at the AED and the commencement of diagnostic examinations (QKSR) | 0.71 | 87% |

| 11. A patient with suspected stroke, regardless of severity and neurological deficit, must be placed in bed, supine (QKSR) | 1.00 | 100% |

| 12. In patients with suspected AIS, blood pressure should be measured on both arms and a finger stick glucose test performed (QKSR) | 0.59 | 80% |

| 13. Hypotension and hypovolemia should be treated before starting thrombolysis (QKSM) | 1.00 | 100% |

| 14. Thrombolysis must be administered to eligible AIS patients within a time-window of 3 hours (QKSM) | 0.57 | 80% |

| 15. Patients aged over 80 years should be excluded from thrombolysis (QKSM) | 0.47 | 80% |

| 16. In an AIS patient about to receive thrombolysis, the maximum acceptable body temperature is: i) 37 °C, ii) 37,5 °C, iii) 38 °C, iv) 38,5 °C (QKSM) | 0.25 | 73% |

| 17. The lowest acceptable blood glucose level for a patient about to receive thrombolysis is 60 mg/dl (QKSM) | 0.86 | 93% |

| 18. If the patient that is about to receive thrombolysis demonstrates an oxygen saturation of <94%, we administer oxygen via nasal cannula and proceed with thrombolysis as planned (QKSM) | 0.66 | 87% |

| 19. What is the recommended dose of rt-PA in an AIS patient? i) 0.9mg/kg, ii) 90mg/kg, iii) 0.6mg/kg; iv) 1.3mg/kg (QKSM) | 0.86 | 93% |

| 20. What is the maximum acceptable blood pressure before administering thrombolysis? i) 200/115mmHg; 230/115mmHg; iii) 215/120mmHg; iv) 185/110mmHg (QKSM) | 0.42 | 87% |

| 21. During the administration of thrombolysis, blood pressure must be measured every 30 minutes (QKSM) | 0.66 | 87% |

| 22. Administration of aspirin is recommended within 24 to 48 hours after thrombolysis (QKSM) | 0.81 | 93% |

| 23. Thrombolysis can be administered to an AIS patient who is receiving a therapeutic dose of heparin (QKSM) | 0.42 | 87% |

| 24. Maximum allowed dose of r-tPA is 40 mg (QKSM) | 0.84 | 93% |

| 25. For thrombolysis to be administered, blood tests, chest x-ray and electrocardiogram must all be completed (QKSM) | 0.81 | 93% |

| 26. After thrombolysis treatment, the patient must be transferred to an ICU for 12 hours (QKSM) | 1.00 | 100% |

| 27. In a patient who has received thrombolysis, vital signs should be taken regularly only during the first 12 hours receiving r-tPA (QKSM) | 1.00 | 100% |

| 28. In a patient with a severe stroke and large-vessel occlusion, thus with an indication for thrombectomy, we immediately administer thrombolysis (if the patient is eligible for that) and thrombectomy follows (QKSM) | 0.86 | 93% |

| Nurses | Physicians | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where did you last receive stroke education or training? | Ν (%) | Ν (%) | Ν (%) |

| Self-guided study | 3 (2.2) | 2 (10) | 5 (3.2) |

| Congress/ educational workshop | 49 (35.8) | 8 (40) | 57 (36.3) |

| Class (post-graduate level) | 6 (4.4) | 1 (5) | 7 (4.5) |

| Class (undergraduate level) | 38 (27.7) | 8 (40) | 46 (29.3) |

| Brief presentation on stroke care | 37 (27) | 0 (0) | 37 (23.5) |

| Leaflet/ other printed material | 4 (2.9) | 1 (5) | 5 (3.2) |

| Total | 137 (100) | 20 (100) | 157 (100) |

| Nurses | Physicians | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Total score | 12.6 (4.1) | 15.7 (4) | 12.9 (4.2) |

| General knowledge on stroke (4 items) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.9) |

| Stroke recognition (8 items) | 3.9 (1.6) | 5 (1.5) | 4 (1.6) |

| Stroke treatment (16 items) | 5.2 (2.7) | 7 (2.4) | 5.4 (2.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).