1. Introduction

Philosophical contemplation grounded in the realm of language is an integral issue inherent in the very genesis of philosophy. The exploration within the philosophy of language is centered around the relationship between the generic form and content of language, and the interplay between the form and content of conceptualization. This venture either embarks systemically from language, proceeding along the linguistic path to elucidate philosophical queries, or it aims at the philosophical comprehension intrinsic to a particular language, or ultimately, it centres around the interrelationship between philosophy and language. Therefore, differing forms of the philosophy of language manifest, albeit all these forms fundamentally scrutinize the language from the perspective of its profound significance to humanity (Wang, 1999:8). Viewed through the lens of the philosophy of language, the emergence of the constrained world of appellations and distinctions owes its origin to renowned sayings. LaoTze advises individuals against the misuse of such sayings and distinctions and to remain vigilant against the illusions created by language: “Once

Ming has been established, it is also essential to know when to stop. The knowledge of when to halt can forestall disaster”

1. LaoTze’s philosophy encapsulates three salient characteristics: “

Tao is natural”

2, “

Tao constantly does nothing yet leaves nothing undone”

3, and “The great image has no form,

Tao is hidden and nameless”

4. Given that “nature” is relative to “man-made” and “man-made” is contrasted with “nonaction”, the attributes of

Tao can be succinctly encapsulated as natural, nonaction, and confluence into formlessness. The essence of

Tao is chaotic and formless, pervading as one, it is boundless in space and eternal in time, and it is beyond the grasp of any language that hinges on form and distinction. Expressing the indistinguishable

Tao with a language replete with distinctions can only lead to limited knowledge and infinite disputes, resulting only in the devastation and desecration of the “Great Way of the Universe”. Only by adhering to “

Tao of not telling

Tao” and engaging in the “argument of nonargument” can one return to the undivided, infinite realm of

Tao (Zhao, 2007:16). Given that every individual harbors their own notions of right and wrong and that things possess the duality of being both possible and impossible, correct and incorrect, language ultimately culminates in one-sidedness. The entire cosmos is an infinite process of transformation, limitless in both time and space, and any comprehension articulated through language is nothing more than a limited, myopic perspective, unable to encompass the entirety of things. Language fragments

Tao, ultimately concealing its true nature.

This study offers valuable references for subsequent research. Moreover, given the current context of globalization, where East-West cultural exchanges are increasingly intertwined, research on LaoTze and Tao contributes to preserving and promoting the splendid traditional Chinese culture and fostering mutual understanding and communication between Eastern and Western cultures.

2. Literature Review

In the pursuit of understanding LaoTze’s Tao, scholars have adopted a plethora of methods for interpretation, such as comprehending the significance of Tao from the perspectives of ontology and nominalism (Wu, 2022:132), and scrutinizing LaoTze’s philosophy of “governing Tao” from the dimensions of ontology, axiology, and boundary theory (Xu, 2016), among others. Furthermore, attempts have been made to analyze LaoTze’s Tao using modern scientific methods, such as the application of axiomatic methods in the interpretation of LaoTze (Gan, 2016). These research methodologies not only enrich the connotation of LaoTze’s Tao, but also provide fresh perspectives for comprehending and inheriting LaoTze’s philosophical thoughts.

Literature quantitative approach will be applied in this part, employing scientometrics and visualization via Bibliometrix to analyze LaoTze-themed literatures on the Web of science, providing insights into research status, trends, and hotspots. Just as CiteSpace or VOS applied in translation or linguistics research for more accurate visual analysis (Xiong et al., 2023; Alduais et al., 2022), scientific knowledge mapping can offers us a detailed visualization map of scientific development and relations within large data sets.

2.1. Data Collection and Methodology

Data is crucial in empirical research, and for a comprehensive understanding of international LaoTze studies, it's essential to select proper data samples. This study opts for high-quality journal articles, books, and conference papers on LaoTze as research objects, a method endorsed for reflecting research conditions. Utilizing the WOS core database, the study retrieves documents using “Laozi”, “LaoTzu”, and “LaoTze” as keywords with Boolean logic, from 1967 to 2023. After deduplication and irrelevant content removal, an expert review finalizes 117 literature samples for analysis.

This study investigates the current state and research trends of international LaoTze-related research from three levels: basic overview, research themes and hotspots, and future research. Firstly, the basic overview comprises literature distribution time, highly-cited journals, and significant authors within the field, aiming to summarize the overall development trend of LaoTze-related international research and identify the disciplinary foundation and high-impact authors. Secondly, to clarify research topics and understand research progress, this study analyzes literature keywords, first refining research themes through keyword clustering knowledge maps, then displaying research hotspots via keyword co-occurrence maps. Lastly, the study examines the trends in international LaoTze research through keyword theme evolution analysis.

2.2. Retrieval and Analysis

The literature distribution time can directly reflect the changing patterns and trends of a discipline within specific time periods and serves as an essential indicator for analyzing the research situation of a subject and predicting future trends.

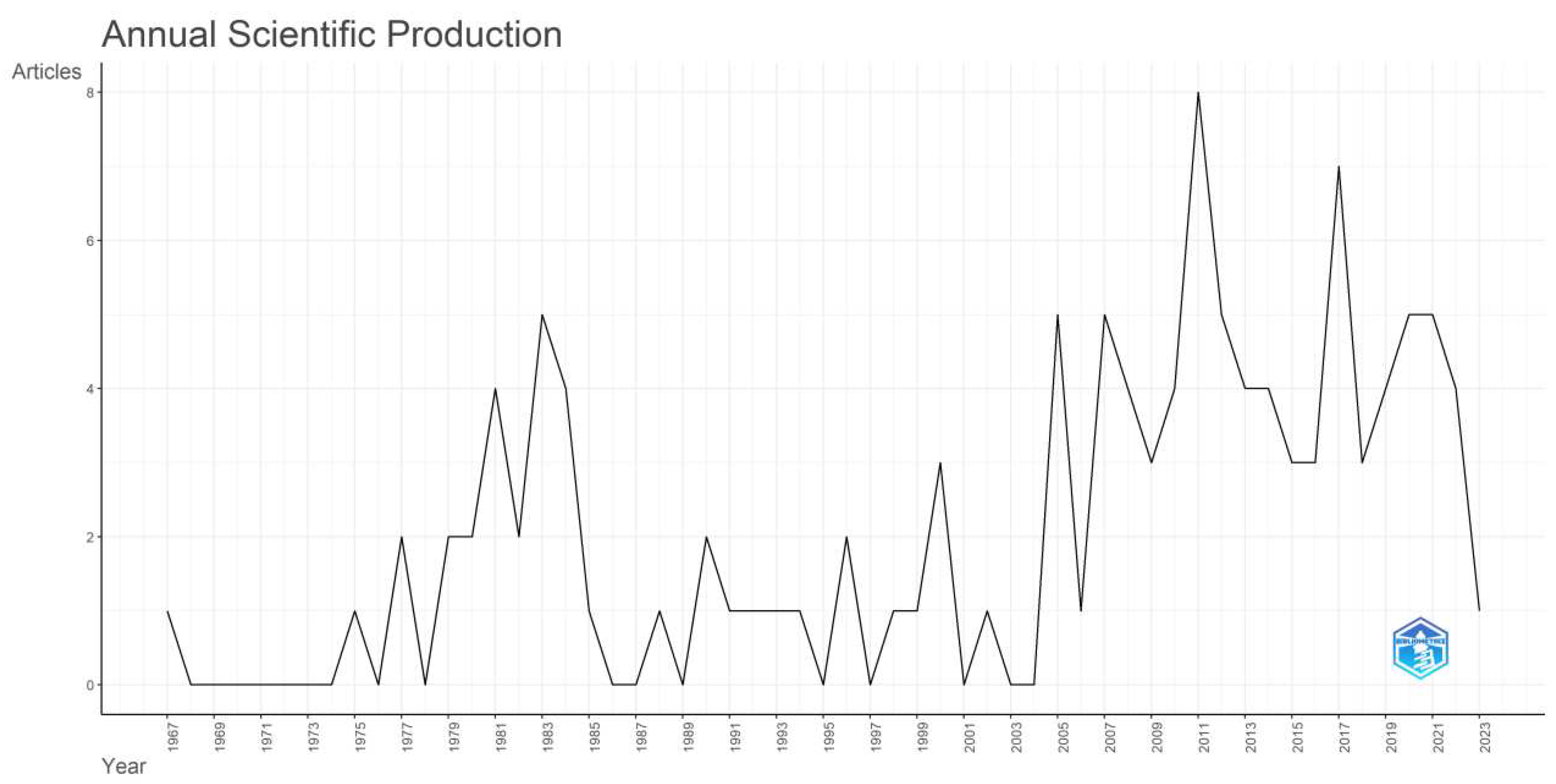

Figure 1 presents the publication time trend of LaoTze-related research results from 1967 to 2023.

From 1967 to 2023, within the WOS core journals, there were 117 publications regarding the study of “LaoTze.” The overall annual production trend is illustrated in

Figure 1. As can be discerned from the graph, the annual publication volume within the field exhibits a fluctuating upward trajectory. Between 1967 and 1979, the annual publication volume remained below ten articles. The growth commenced in 1979, but between 1979 and 1983, it was gradual, accompanied by minor fluctuations. From 1984 to 2003, the publication volume experienced a precipitous decline, entering a trough. This situation began to improve in 2005 when Ellen M. Chen explored some key aspects of Heidegger’s thought and compared them to the perspectives found in

Tao Te Ching. This assessment measured the extent to which Heidegger deviated from the Western tradition, ultimately moving towards Taoist philosophy (Ellen, 2005). This unique angle provided a foundation for subsequent LaoTze studies, demonstrating how Taoist thought influenced the thought processes of Western philosophers, and sparked a surge of scholarly discussion on LaoTze’s ideas among Eastern and Western academics. Consequently, between 2005 and 2022, the publication volume exhibited a rapid development trajectory, culminating with a peak of eight publications in 2011. However, in a broader context, international research pertaining to “LaoTze” remains relatively scarce, and its global impact is insufficient.

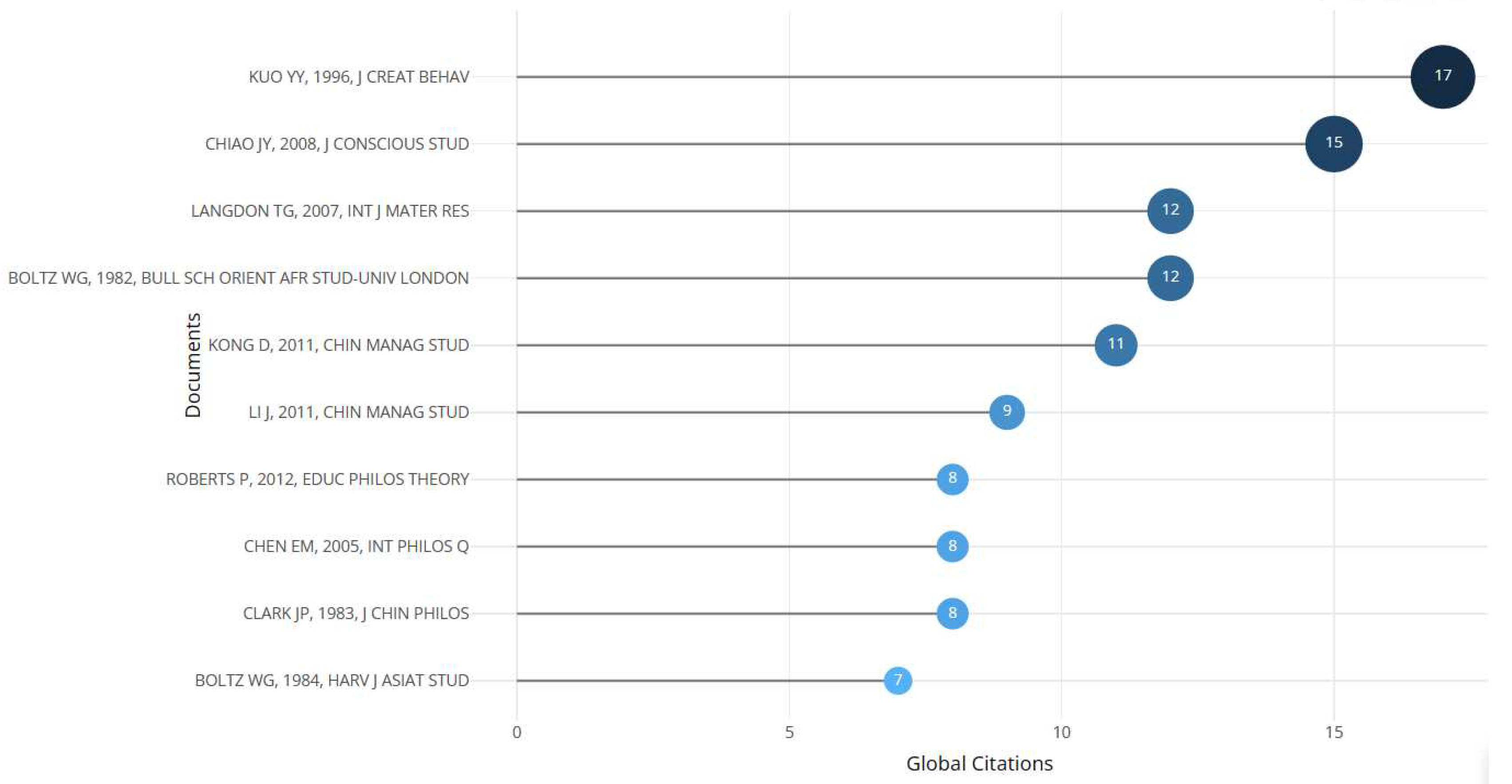

Analyzing top scholars (≥10 citations),

Figure 2 reveals a bifurcation in LaoTze research themes: theoretical Taoist philosophy and applied Taoist thought studies, spanning psychology to resource management. LaoTze's ideas influence cognition, objectivity, creativity, impacting areas from artistic to scientific realms, psychological well-being, and human resource management. Emphasizing morality and a people-centric perspective, LaoTze's wisdom can enhance organizational harmony and innovation (You, 1996; Boltz, 1982; Chiao et al., 2008; Dong, 2011).

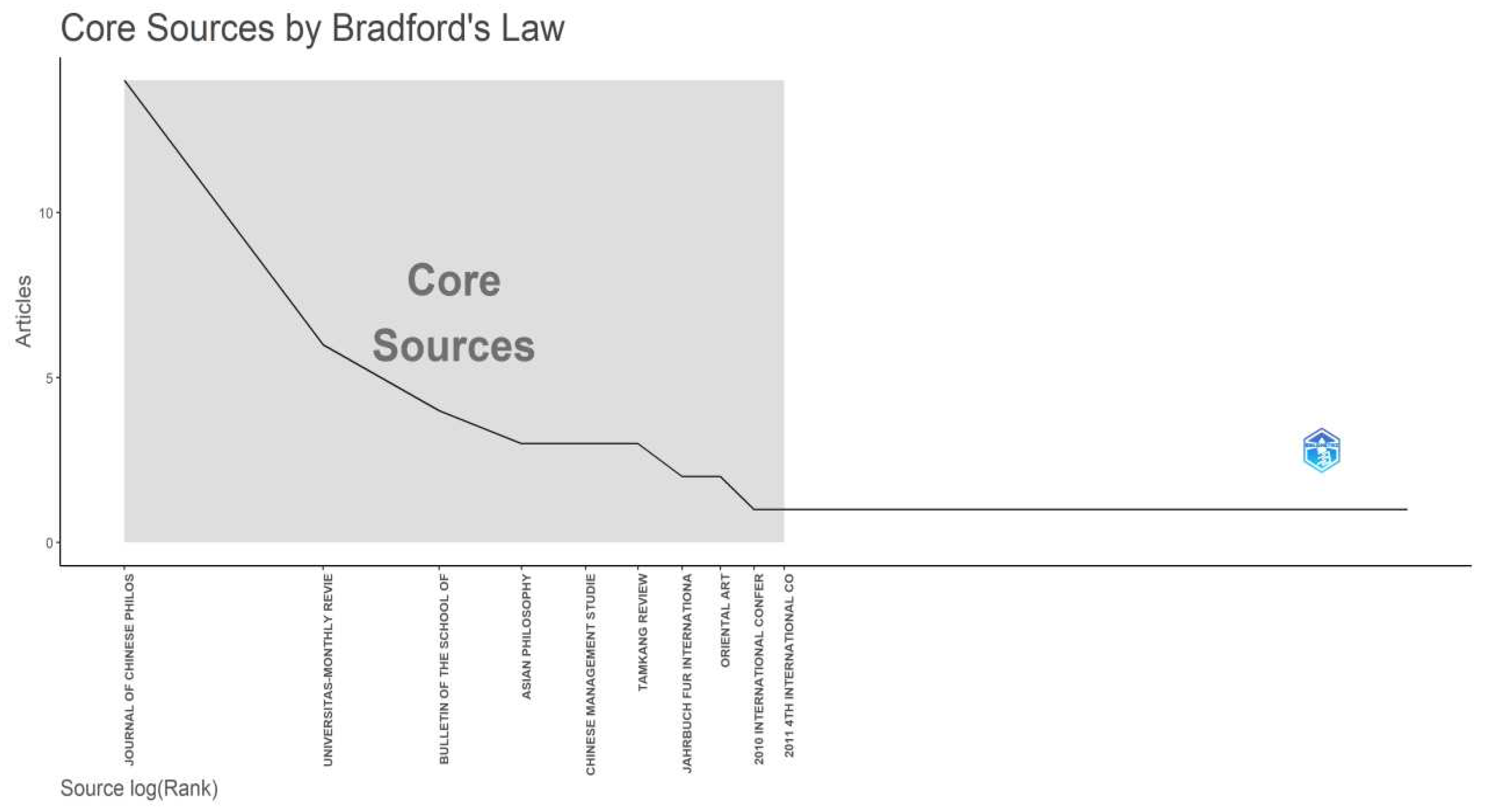

Journals channel scholarly findings and frequent citations highlight influential literature.

Figure 3 shows the prominence of the

Journal of Chinese Philosophy,

Universitas-Monthly Review, and

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, particularly in philosophy, culture, and humanities. The Bulletin is especially influential, covering a wide range of disciplines and attracting a broad readership. This analysis reveals research findings are published across various journals, not just specialized ones, evidencing the interdisciplinary nature of LaoTze studies. It suggests a broad international interest in LaoTze-related themes from multiple disciplines, underlining the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in research.

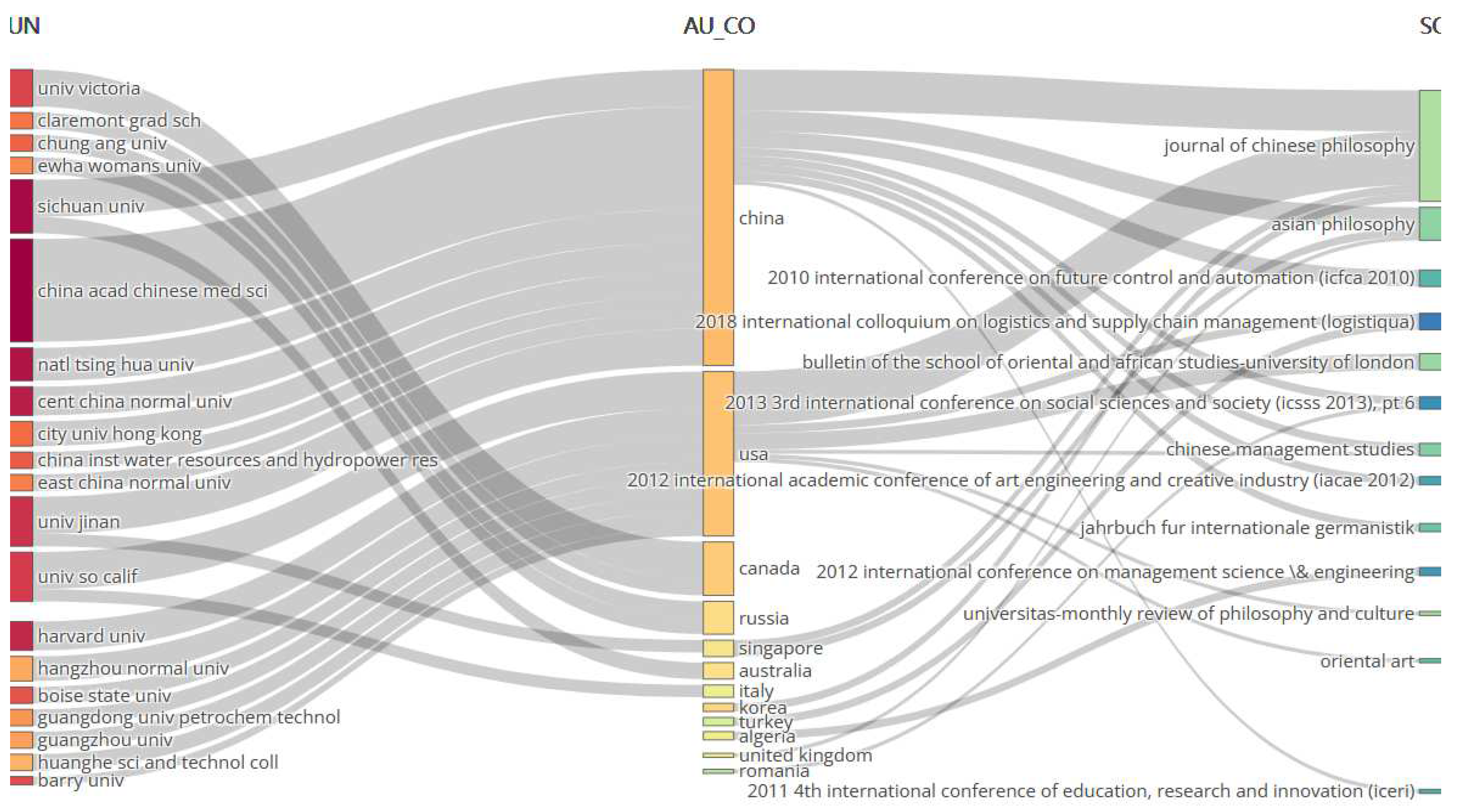

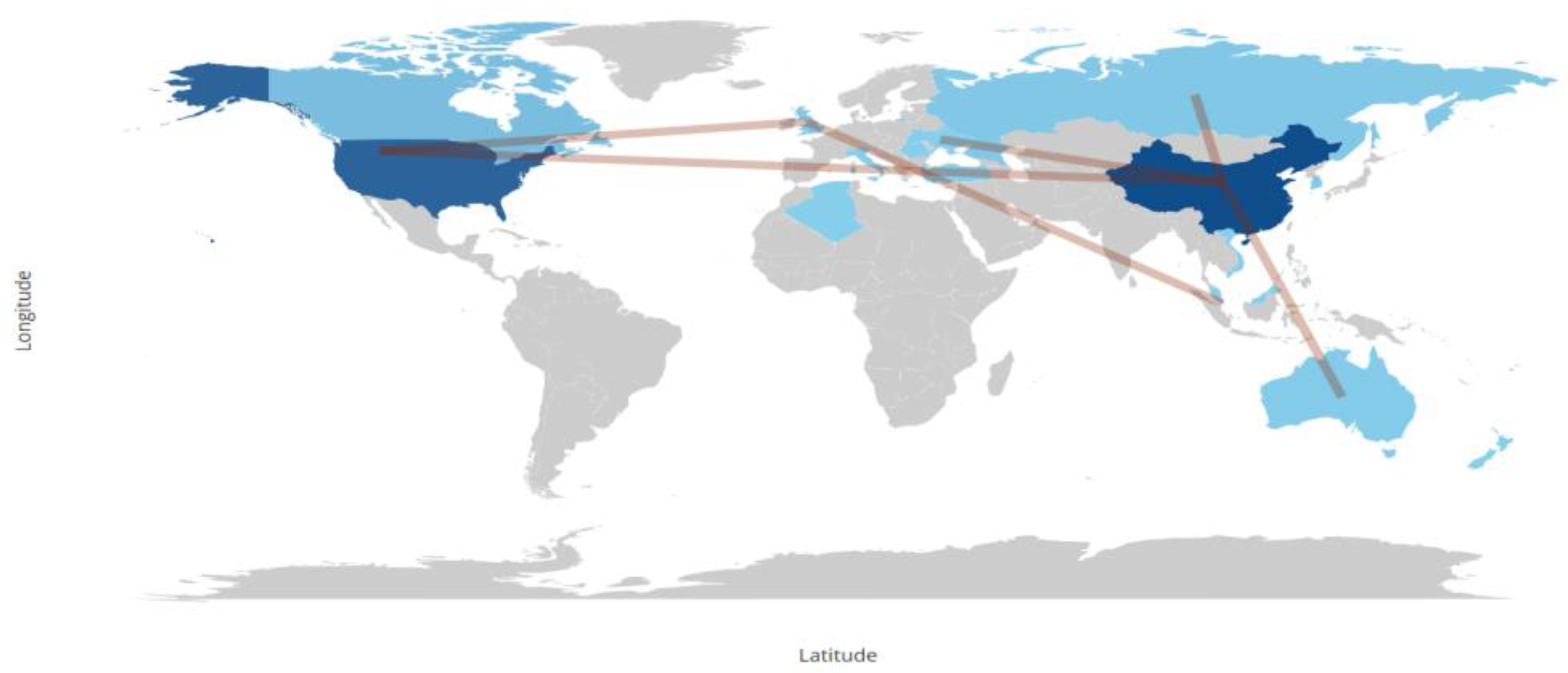

Sankey diagrams in literature studies reveal discipline, author, and method links, showing research trends and aiding in finding research avenues and collaborations (Schmidt, 2008). China leads in connections (17), followed by the US (14), Canada (3), and Russia (2) (

Figure 4). China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, Sichuan University, and Jinan University are China's top institutions. Both China and the US are notable in the Journal of Chinese Philosophy, while China and Singapore lead in the Asian Philosophy. Chinese scholars are prominent in researching LaoTze, excelling in philosophical, comparative, and academic studies (Wang, 2017; Zhang, 2017).

Scholarly collaboration denotes the collective endeavor undertaken by researchers to engender novel scientific knowledge, manifesting in myriad forms and expressions. The appearance of diverse authors, institutions, or even countries/regions within a single published article is indicative of an established collaborative relationship (Li & Chen ,2016: 180). The present investigation endeavored to delineate the network of international collaborative relationships to comprehend the mutual cooperation among various nations engaged in research. As portrayed in

Figure 5, it involves researchers from varying countries, notably China and the US, and is key to advancing scientific knowledge. This collaboration is still limited but has the potential for growth. It is most prominent between Chinese and American scholars.

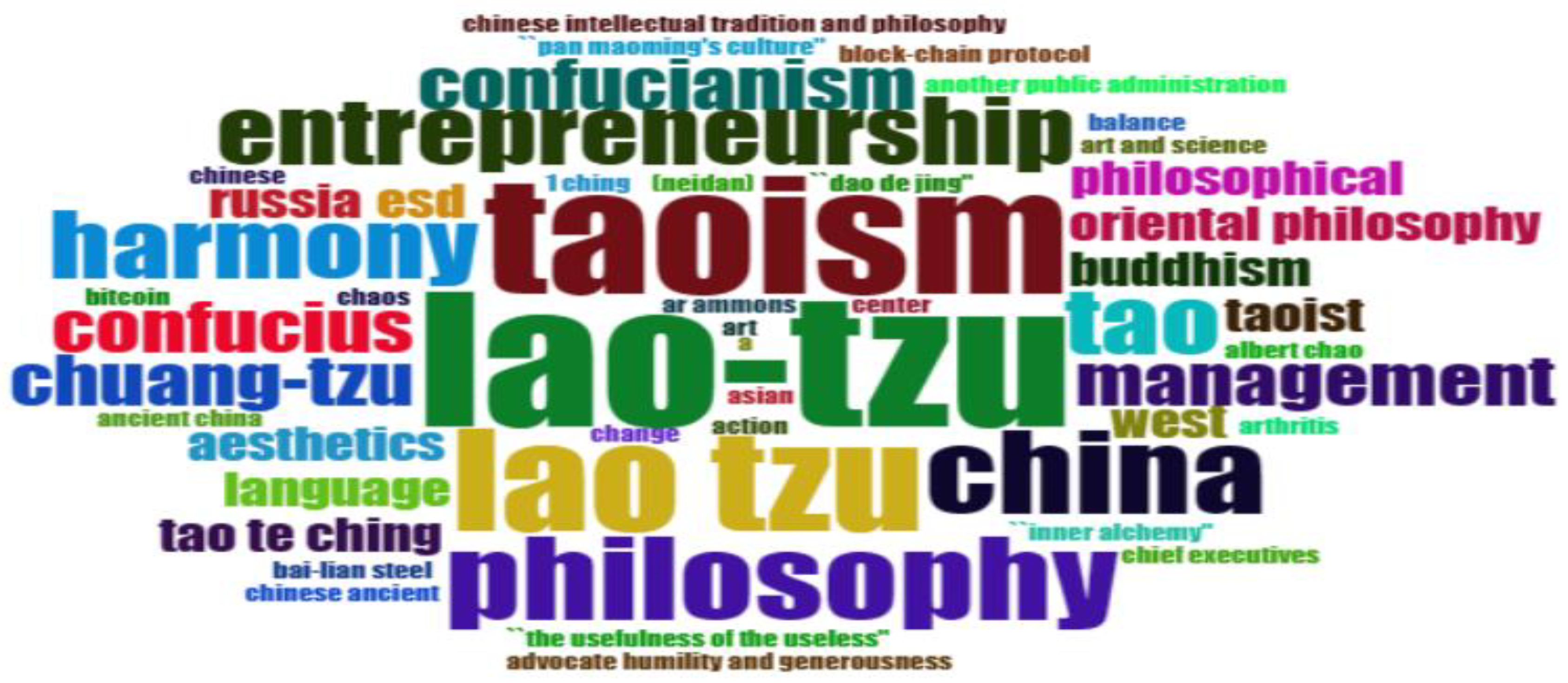

The keywords of a paper represent a highly distilled encapsulation of its core content, while keyword cloud analysis entails a frequency-based enumeration of the focal keywords within a body of literature, visually accentuating those with higher occurrence rates to form a keyword cloud that facilitates the discernment of the article’s thematic essence for readers. In Biblioshiny, the creation of a keyword cloud can be achieved through the following pathway: Descriptive Analysis - Plot - Word Cloud.

Figure 6 presents the keyword cloud for international research, from which it is evident that the prevailing foci of scholarly inquiry are concentrated on topics imbued with rich Chinese cultural hues, such as Taoism, LaoTze, Oriental philosophy, and

Tao Te Ching. In conjunction with the analysis of active international scholars and collaborative institutions detailed earlier, it can be discerned that Chinese academics are striving to introduce and disseminate LaoTze’s philosophical ideas on the global stage.

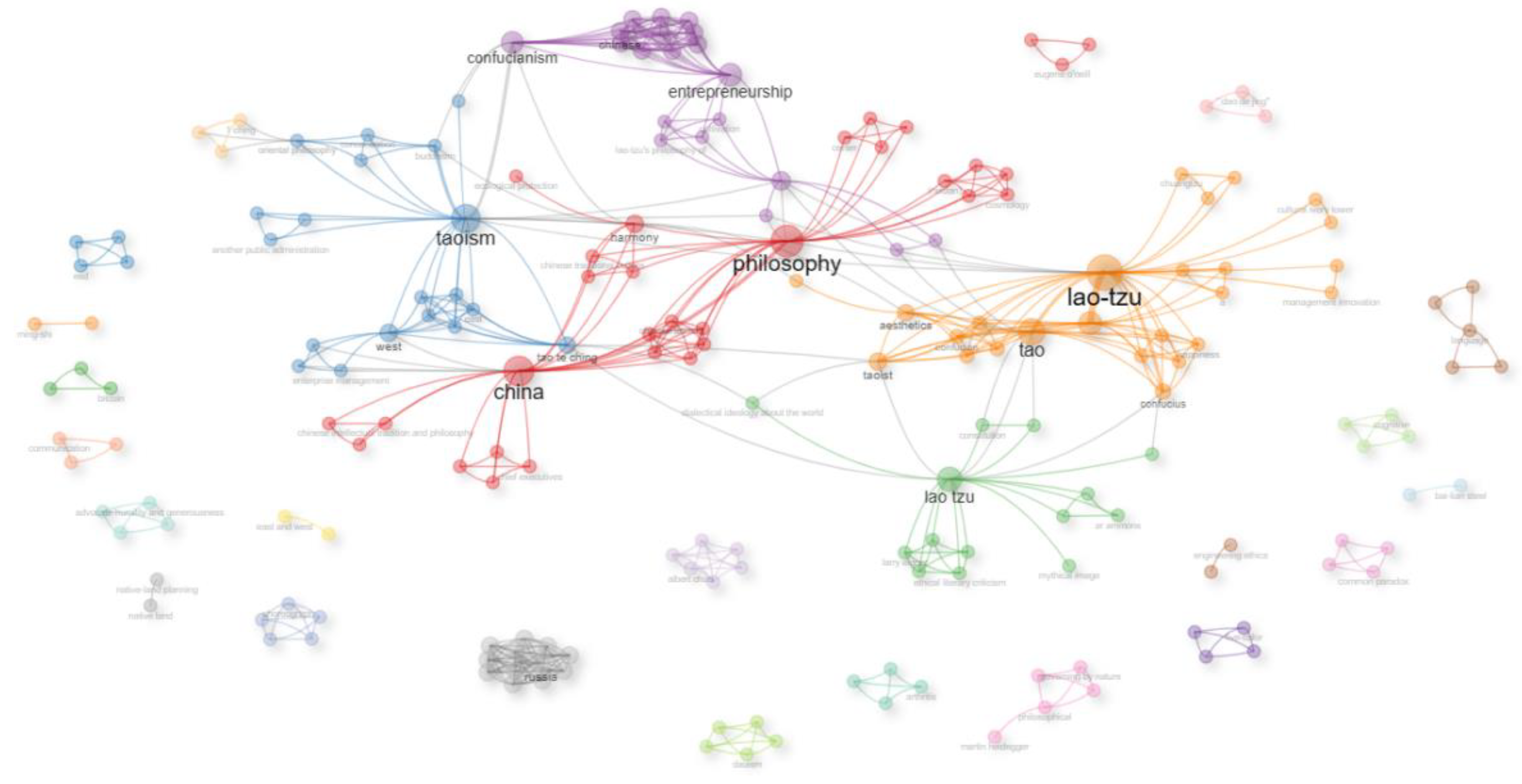

Keyword co-occurrence forms a co-word network that reveals research hotspots and tracks developing trends. Each node represents a keyword. The font size of a node in the diagram signifies its centrality—the larger the font, the higher the frequency of the keyword’s appearance, the greater its centrality, and the more substantial its impact. In

Figure 7, “Philosophy” resides at the core of the entire graph, boasting the most significant node and exerting the strongest influence. Additionally, other keywords with high centrality appear adjacent to it, such as LaoTzu, Taoism, China, Confucianism, West, Entrepreneurship, Aesthetics, and Education, indicative of recent focus on philosophy, arts and humanities, and education management in the realm of LaoTze-related research.

Given the above keywords and in conjunction with literature content analysis, current research on LaoTze and Tao is progressively deepening, incorporating a broader array of academic fields such as psychological counselling, education, art, and political philosophy (Ai, 2023; Zhao et al., 2023; Minhui & Unshil , 2020). The research perspectives are becoming more diversified, not only concentrating on the inherent ideological system of LaoTze and Tao, but also their dissemination and influence within various cultural contexts.

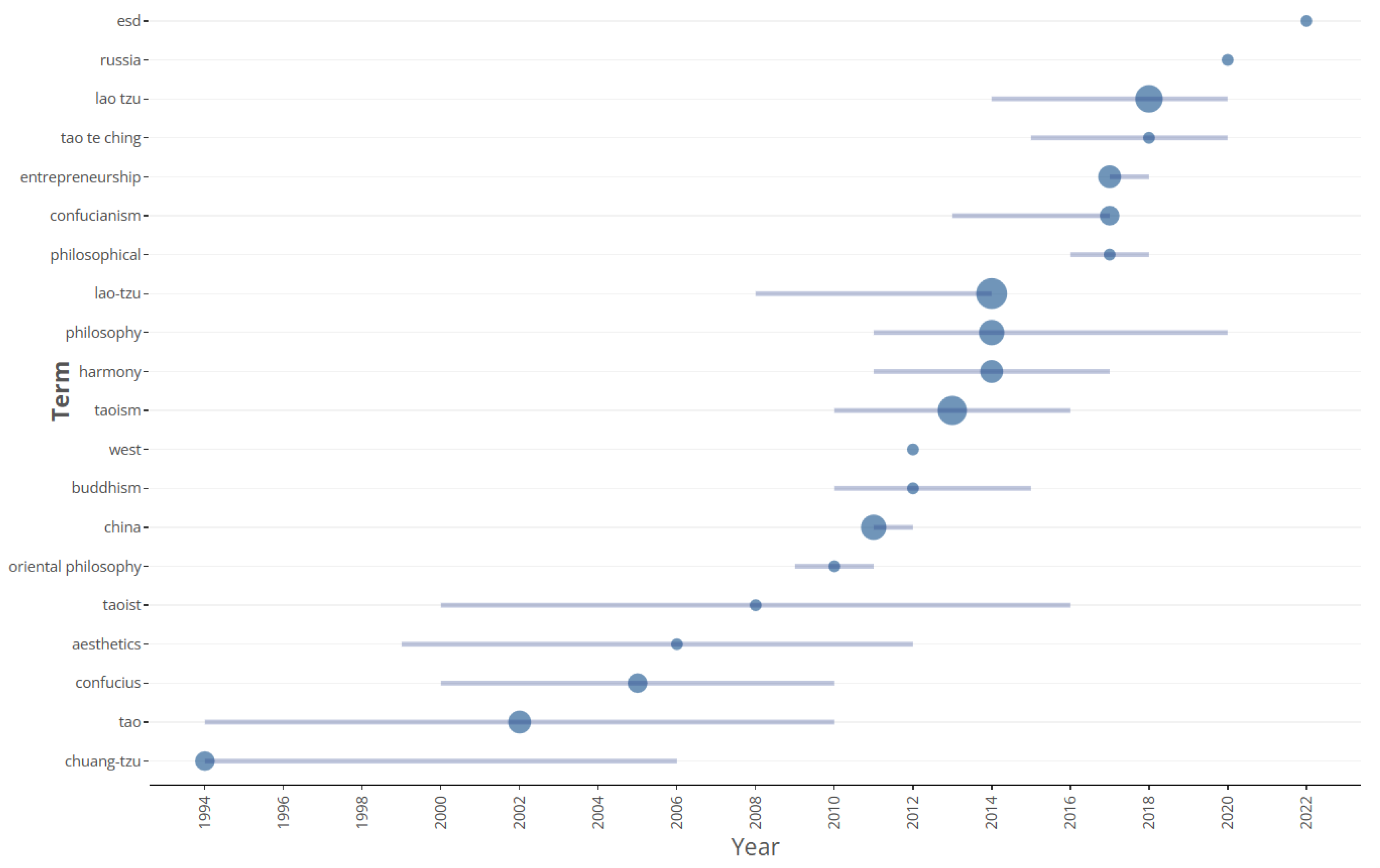

To further comprehend the research trends in this field , this study utilizes the Biblioshiny Rtool package to analyze keyword frequencies in the literature sample, generating a visual representation of the research topic’s evolution (as depicted in

Figure 8). As seen in

Figure 8, research from 1994 to 2005 was in its infancy, primarily focusing on the academic understanding and aesthetic core of philosophical theories from thinkers such as Chuang-tzu,

Tao, Confucius, and Lao-tzu, including explorations and interpretations of the overall outline of Eastern philosophy (Hansen, 1992). Since 2005, with the progression of globalization, research on Taoist philosophy has shifted, gradually adopting comparative philosophical perspectives between East and West, historical and cultural viewpoints, and textual criticism (Moeller, 2007).

3. LaoTze’s Philosophy of Language

Tao and Yan engender and negate each other. The crux of LaoTze’s philosophy of language is ontology and cognition and their verbalization, primarily discussing the relationship between language and the world (Tao/existence), an issue running throughout the entirety of Tao Te Ching. The structure of the Chinese language differs from that of Western languages, and for the exploration of ontology, the “fundamental ontology” of the Chinese language should serve as the benchmark (Chen, 2023:115). Tao or the highest truth about the world’s primordial origin can be expressed, yet it transcends the capabilities of ordinary language. This condenses the role of language, affirming its ability to express thoughts while simultaneously acknowledging its limitations (Huang, 2006:175). This insinuates that there exists an inherent contradiction and chasm between the original world and the world articulated through language: “Tao that can be spoken of is not the unchanging Tao; the Ming that can be named is not the unchanging name. Nameless, it is the beginning of heaven and earth; named, it is the mother of myriad things. Always devoid of desire, one can observe its subtleties; always possessing desire, one can observe its manifestations. Both of these emerge together but are named differently. The profundity of profundity, the door to all subtleties.” If Tao can be articulated in words, then it is the unchanging Tao, capable of being verbalized, and not the ordinary Tao; if a Ming can be conferred through words, then it is the unchanging name, capable of being elucidated, and not the ordinary Ming. “Nonexistence” can be utilized to depict the state of chaos prior to the advent of heaven and earth, while “existence” represents the naming of the original source of the cosmos. Consequently, one should continually observe and grasp the mysteries of Tao from the “nonexistence” and observe and experience the clues of Tao from existence. Both “nonexistence” and “existence” originate from the same source but bear different names, and both can be regarded as profound and distant. It is not merely profound and mysterious but also profound upon profundity, distant upon distance, and it is the portal to the mysteries of the cosmos and all things. From the mysteries of the “named” to the mysteries of the formless, Tao is the path to delve into all profound changes. Here, LaoTze emphasized that Tao could not be spoken of or named and that what could be spoken of or named was no longer the primordial Tao. From an evolutionary perspective, Tao is originally nameless, and the “nameless” give rise to the “named”, which is a process in line with the laws of nature. From an ontological perspective, Tao must be both “nameless” and “named”; otherwise, the origins of the Ming can not be elucidated.

Nevertheless, to deny that

Tao can be spoken of is in itself a metaphorical and indicative act of speaking about

Tao, albeit in a negating sense. Simultaneously, the transcendent nature of

Tao, beyond language and imagery, paradoxically ensnares it in the intricate web of language.

Tao, albeit nameless, engenders a plethora of pseudonyms due to its very indefinability. The relationship between

Tao and

Yan shifts the focus to language itself, resembling the scrutiny applied to

Tao. If

Tao cannot be referred to with a name or even any noun, then language (or names) cannot trespass into the realm of

Tao. Evidently,

Tao itself repudiates conventional language (i.e., names, appellations). Given that

Tao only possesses essence, devoid of phenomena or attributes, it remains eternally inscrutable to ordinary language, precluding its description, definition, or approximation (Wei, 2010:16). “Trustworthy words are not beautiful; beautiful words are not trustworthy,”

5 disclaimed LaoTze, renouncing the cognitive function of ordinary language: authentic speech lacks elegance, whereas elegant language forfeits authenticity. Speech, by denoting, constructs various dimensions of the world, generating discursive meaning on the dimensions of denotation and connotation: in the societal world, discursive meaning manifests as an emphasis on the performative force and postspeech effects on the pragmatic level (Huo, 2020:128). LaoTze’s

Tao is not a linguistic activity of humans but rather belongs to the realm of human cognitive process. The content of human thought can be expressed through the medium of language. However, the boundlessness, ambiguity, and continuity of thought mean that the material form of language can only express fragments and aspects of the cognitive process; hence, the saying “What can be spoken of is not the eternal

Tao.” Based on such a recognition of language, LaoTze emphasizes “Excessive speech causes exhaustion, it is better to remain moderate”

6 and “Great eloquence seems hesitating.”

7 By associating blunt speech with the most fundamental

Tao in his philosophy, LaoTze highly exemplifies his treasuring of

Yan, which can also be interpreted as a repudiation of the efficacy of general language from another perspective.

4. Modern Western philosophy of language

The focus of contemporary philosophical discourse has pivoted from the dichotomy of subject and object to the interplay between language and the world, from a dualistic perspective to a unified perspective. Humanity represents the cognitive subject, while the world is the object of cognition; it is only through humans that language is birthed and expressed. The world itself lacks language or the capacity to articulate, making language a mirror that reflects the world. It is not humans who speak language, but language that speaks humans. This uncovers the relationship of reflection and being reflected between language’s subject and object, the relationship of perception and being perceived between senses and content, and the social and linguistic relationship of convention and being conventional.

The distinguished German philosopher Martin Heidegger posited that “language is the house of Being,” and “language is the indispensable mediator between man and existence.” Language integrates man with the world, imbuing the world with meaning through language (Heidegger, 1997:252). Language speaking is the ability to articulate without articulating, Sage. Abstract ontological thinking is ineffable in the language of rationality, logic, or concept. “Language is not merely one of many tools possessed by man; only language provides a possibility of being placed within the openness of existence. Only where there is language, there is a world” (Heidegger, 1996:314). Where there is language, there is a world. Human existence is based on language; language is no longer the vessel of thought but thought itself. There is no naked thought outside of language.

Analysing the relationship between language and meaning from the perspective of modern language philosophy, it could be found that the reasons why language cannot fully express meaning are as follows: first, people have not truly clarified the relationship between language, thought, and reality; second, people have confused the relationship between semantics and thought; third, people have failed to truly grasp the characteristics of language's function to convey meaning (Yu &Wang , 2021:22).

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein, a major representative of the linguistic school, once said, “The richness and poverty of my language mean the limits of my thoughts (Wittgenstein, 2007:326).” Wittgenstein hoped to reveal what exactly occurs when people express themselves in communication through studying language itself. He advocated that the essence of philosophy is language. Language is the expression of human thought, the foundation of the entire civilization, and the essence of philosophy can only be sought in language. Thus, the “language first” status transitioned from a tool reflecting and representing objects by the subject (people) to a status of precedence: It is not man who speaks language, but language that speaks man; language speaks first, the world spoken by language transcends man, and man’s speech is merely an “echo” of language’s speech (Kang, 2004:16). German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer proposed that “A being that can be understood is a language” and “there is no world outside of language” (Gadamer, 1993:356). That is, language is existence (Sein).

China’s semiclosed continental geographical environment and self-sufficient small-scale farming economy led to traditional holistic thinking, viewing all things as part of a network of relationships and considering them as a whole rather than breaking down the whole into parts for individual analysis and research, emphasizing the harmony and unity of diversity and opposition. Westerners view the living environment as external, acknowledge the opposition between man and nature, and thus explore and conquer it. Therefore, Westerners focus on detailed and thorough analysis and rigorous reasoning of things, study the essence of things through phenomena, form advanced abstract thinking, strict logical reasoning methods, and detailed division of various disciplines. Hence, their thinking is dispersed.

Language is not only a tool for human thinking but also a means of generating knowledge. The conclusion of agreements largely depends on whether people can successfully implement speech acts (Tang, 2022:112). Paul Ricoeur grasped the distinction between language and speech in Saussurean structuralist linguistics and creatively proposed a discourse theory of the existence of the “world” and “human” (Che & Guo, 2018:23).

The history of Western thought development believes that the so-called truth is the consistency between language and the object it refers to. This sentence contains two implications. First, humans can cognize objects and encapsulate the results of cognition in language. Second, the consistency between language and the object it refers to is truth (Huang, 2006:174). The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure said in Course in General Linguistics: “Psychologically, hought without the expression of words is just a shapeless, vague, and nebulous entity. Philosophers and linguists generally agree that without the aid of symbols, we cannot clearly and consistently distinguish between two concepts. Thought itself appears to be a nebulous cloud without definite boundaries. Preestablished ideas do not exist, and everything is vague before the emergence of language (Saussure, 2001:391).”

5. Ming/Yan and Language

Language serves as a tool for expressing thoughts and as a material embodiment of cognition. Can it truly convey our intentions—that which our minds perceive and grasp—with clarity and completeness? What can be articulated with lucidity, and what cannot? For those aspects of existence that exceed the realm of verbal expression, if they do exist, how can they be represented and understood by others? In other words, is comprehension reliant solely on language, or can alternative approaches be taken? What underlying principles determine the solutions to these conundrums? These debates, centered around the relationship between language and meaning, has long confounded linguistics scholars from both Eastern and Western traditions and remains a central issue within our academic discourse.

Chinese traditional philosophy, recognizing the limitations of language’s expressive capabilities, places importance on the comprehension of meaning beyond language, differing from Western philosophy’s emphasis on language logic and the pursuit of certainty in language expression. Due to such linguistic perspectives, traditional Chinese culture does not prioritize clear and rigorous logical reasoning, as the precision of logical reasoning fails to overcome the limitations of language functions. Therefore, Chinese culture exhibits a focus on intuitive understanding (Wang, 2008:3).

Chinese thinkers have always believed that language cannot fully reveal objective facts and subjective will; language is limited and unable to express the inner thoughts of the cognitive subject adequately. LaoTze posits that the natural Tao cannot be grasped by using language to describe it; if one must use language to express it, it can only be done reluctantly. Often, language’s expression of thought is limiting and even detrimental. An excessive adherence to linguistic form may culminate in obfuscation, while an overzealous pursuit of ornate rhetoric often falls short of fully conveying one’s thoughts, ultimately leading to a perversion of meaning. (Kang, 2004:15). LaoTze states, “Truthful words are not beautiful; beautiful words are not truthful. The virtuous need not debate; those who debate are not virtuous.” “Profound skill appears clumsy; great eloquence appears hesitating.”

LaoTze’s linguistic thoughts are part of his language philosophy. Employing Heidegger’s words, LaoTze endeavoured to use language to reveal existence while simultaneously manifesting his own existence. Therefore, we today can delve deeper into the implicit linguistic thoughts in his philosophical ideas, as revealed by LaoTze’s portrayal of existence through language and his own existence (Huang, 2006:175). Language is explicit, while Tao is implicit; nevertheless, Tao can articulate itself through the substance within words, making unspoken statements. Gadamer also noted that “what is said always carries within it an element of the unsaid” (George, 2009:185). According to this perspective, LaoTze’s “Great Way of the Universe” resembles language speaking; the Sage’s words are those that can speak but remain unspoken, being primordial and distinct from human speech. The existence of Tao does not depend on human conceptual language. The focus of conceptual language is solely on the present, while Tao and other linguistic expressions integrate both presence and absence, harmonizing all things (Kang, 2004:17).

Ming, or the distinctive features of words, often entails judgments concerning human ways of thinking. The formation of a Ming, in essence, stores the creator’s understanding of a thing for future generations to reference. By grasping the observed forms, we can gain a deeper understanding of the objects designated by words (Huang, 2006:174). Renowned German philosopher and historian of philosophy, Ernst Cassirer, discussed in his work An Essay on Man that the naming of a thing is based on a form of observation, while different names reflect different forms of observation. The primary function of language is classification. Classification relies on language, naming things and phenomena. Once things and phenomena have specific names, the chaotic world becomes clear and orderly in our minds. Humanity can gradually transform the natural world into a cultural world using language, and language serves to manage the world (Cassirer, 2009:456).

6. Tao and Existence

Tao within the realm of ontology is an indescribable “existence”, and in epistemology, it is a comprehensible “nonexistence”. LaoTze’

Tao represents the latent actuality yet to be revealed, imbued with inherent factors or forces of creation. This enables it to generate existence from nonexistence, manifesting the perceivable universe teeming with named, shaped, finite entities.

Tao is thus a paradoxical existence—simultaneously being and not being. One could argue that

Tao that can be told is not the eternal

Tao; rather, it aligns with the concept of the “vessel” from “When the uncarved block is split, the vessels are born”

8. As an existence within our consciousness,

Tao is ineffable; it cannot exist in the form of language. Language is but an existence, a description or expression of “being” itself, which is not equivalent to existence per se. However, as our first encounter is with a broad sense of language, to a large degree, language and existence, or the so-called

Tao, have mutual connotations. We use language to understand existence, to comprehend “being”, and due to the limitations of language itself, our responses to the ultimate existence, greatly vary. Nevertheless, LaoTze postulates that a resolution for this contradiction can be found through a mystical intuition, which would consequently resolve the conflict between language and existence. In his view, all the multitudinous objects in the universe and their transformations proceed from nonexistence to existence and from existence to nonexistence—a shift from one form of existence to another.

While the West has spent more than two millennia exploring the essence, particles, numbers, “absolute truth”, “God”—the ontology of things until a “linguistic turn” occurred in philosophical circles in the early twentieth century, recognizing that all philosophical questions are intimately related to language and cognition. Wittgenstein (2007: 487) stated, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” He urged a focus on the boundaries of “my world” without considering the limits of the “world”. He may not have proposed a grand view that the common “human world” is beyond investigation, but he implicitly denied the investigation of that world. He also suggests that language constructs my individual world, and the individual world is constituted by language, mirroring the saying “named, it is the mother of myriad things”. These two points are in corroboration with LaoTze’s views. We cannot discuss the whole world within language, nor can we grasp the infinite whole by transcending our own finiteness, nor can we “speak” the whole world from outside the language. This paradox stipulates that discussing Tao is essentially impossible.

Language is one of the most fundamental “symbolic forms” for humans. When language reaches a relatively enriched stage, its outcome can reflect the most abstract cognitive ideologies. Within the context of classical Chinese philosophy, a majority of philosophers recognize the limitations of language functionality. Language cannot straightforwardly reflect the inner world of individuals, nor can it fully and accurately convey the true intentions of a speaker’s thoughts. Language, through the process of cognition, disassembles and selects aspects of the object it refers to, resulting in the abstract and finite nature of the object. This demonstrates the dual function of language—it both reveals and obscures. Revelation manifests through obscuration and vice versa; thus, they share a symbiotic relationship. The dichotomy of language function implies that language inevitably filters out certain content. For Tao, existence that is comprehensive, holistic, infinite, and absolute, its wholeness and infiniteness are dissolved and disintegrated once articulated in language, thereby leading to self-negation (Chen, 2003: 17). LaoTze’s philosophical perspective on language unveils the inherent limitations of language in grasping the essence of existence. Regarding entities such as the “external Tao” (perennial truth) and the “time-tested Ming”, our language and naming are unable to fully articulate them. Tao on the level of language is merely a temporary, reluctant, and necessary method of articulating the highest existence, and we should not be fixated on the Ming itself. Tao is not bound by language, and different perspectives on Tao lead to completely different understandings, sometimes even contradictory conclusions. These differing and even contradictory conclusions demonstrate that no single concept or name can fully reveal the profound and rich meaning of Tao. However, LaoTze does not entirely reject language because of this. In fact, he not only retains language but also advocates for “good words”, proposing standards for them. He informs that his Tao is merely a necessary naming convention and that Tao in language should not be equated with his “eternal Tao” (Wu & Wu , 2009: 5). Tao is a product of chaos.

Modern Western analytic philosophy asserts that the primary task of all philosophy is to address the issue of linguistic analysis (Martinich, 2001: 286). LaoTze affirms the human ability to “name according to facts”

9 Fundamentally, naming depends on reality, but the process of reflecting or naming reality is not entirely passive. Naming also has its active aspect in relation to reality. All things are but surface manifestations of

Tao. In themselves, “all things in their profusion are each returning to their root”

10 that is, not only are all things born from

Tao, but they are also constantly evolving, and in the end, they return to

Tao, their origin. When employing existing names, one must be aware of their relative applicability, that is, the relationship between “name” and “reality” is only relative (Xu, 2006: 56). As objects are perpetually in a state of flux and transformation, human understanding of them inevitably possesses inherent limitations. Consequently, when employing "names," one must comprehend and discern their applicable boundaries.

7. Conclusion

The indigenization of Western linguistic philosophy and the internationalization of Chinese linguistic philosophy is an unignorable theme in contemporary academic circles. A comparative study of the dialectical relationships between Chinese Tao and Name (Yan) and the Western linguistic philosophy, between Language and Existence can better elucidate the trend of Western linguistic philosophy in China's foreign language community. Concurrently, the author of this paper aspires to undertake more profound research into Sino-Western linguistic phenomena through the contrast of concepts in Chinese and Western linguistic philosophies, thus embodying the postmodern philosophical perspective of human-centric existential significance. This is intended to furnish the study of linguistic philosophy with more profitable research methodologies and perspectives, to explore the construction and development of postmodern linguistic philosophy in China, to discuss the translation uncertainties engendered by evolutionary linguistics, to further elevate interdisciplinary research between philosophy and linguistics, to facilitate communication and responses between Chinese and Western linguistic philosophies and to deepen the construction of contemporary Chinese discourse systems.

Author Contributions

Professor Xiong Xin, as the first corresponding author, substantially contributes to the conception, the design of the work, the drafting of the work and the revising of the work critically for important intellectual content, and the final approval of the version to be published. What’s more, contribute to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Ms Liu Xiangtao, as the second corresponding author, contributes substantially to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Informed consent statements: This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Alduais, A.; Ammar, A.K.; Shrouq, A.; Hind, A. Cognitive Linguistics: Analysis of Mapping Knowledge Domains. Journal of Intelligence 2022, 4, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y. Toleration and Justice in the Laozi: Engaging with Tao Jiang’s Origins of Moral-Political Philosophy in Early China. Philosophy East and West 2023, 3, 466–475. [Google Scholar]

- Boltz, W.G. The Religious and Philosophical Signicance of the ‘Hsiang erh’ Lao-tzu in the Light of the Ma-wang-tui Silk Manuscripts. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 1982, 1, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassire. An Essay on Man; (Translated by Li Huamei); Shanghai Translation Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2009; pp. 451–462. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. Research on Chinese Ontology: The View of Existential Categories in Chinese Western Philosophy of Language. Zhejiang Social Sciences 2023, 8, 115–121+160. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, E.M. How Taoist Is Heidegger? International Philosophical. Quarterly 2005, 1, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Y. LaoTze’s Philosophical Thoughts on Existence and the Unity of Heaven and Man. All Things in Three Lives: Collection of Papers on LaoTze’s Thoughts, China, 2003; Volume 5, pp.14-24.

- Che, X.Q.; Guo, J.R. The Source of Paul Ricoeur's Linguistic Philosophy. Foreign Language Journal 2018, 5, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, K.; Jun, J.Z. The Research on Chinese Ancient Management Philosophies' Similarities with Contemporary Human Resources Management Thoughts. Chinese Management Studies 2011, 4, 368–379. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer. 10. In Truth and Method, (Translated by Hong Handing), (Revised Edition); Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- George, V. Hermeneutics, Tradition and Reason. (Translated by Hong Handing). Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2009; pp.

- Hansen, C.A. Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophic Interpretation; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 1992; pp. 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegge. On the Way to Language, (Translated by Sun Zhouxing); Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 1997; 248–260.

- Heidegge. Selected Works of Heidegger; Shanghai: Shanghai Joint Publishing House: China, 1996; pp. 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M. LaoTze’s Philosophy of Language from the Perspective of Naming the Tao. Theoretical Realm 2006, 6, 174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.S. The Philosophical Foundation and Construction of Discourse Research in Contemporary China. Journal of Sichuan University 2020, 6, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.M. A Brief Discussion on the Integration of Chinese Traditional Semantics and Western Philosophy of Language. Journal of Guizhou University for Nationalities 2004, 2, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Er. LaoTze; (Translated by Wei Guanglai); Shanxi Ancient Books Publishing House: Taiyuan, China, 2003; pp. 122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.M. CiteSpace: Science Text Mining and Visualization; Capital University of Economics and Business Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 174–186. [Google Scholar]

- Martinich, A.P. The Philosophy of Language, Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2001; 283–289.

- Minhui, J.; Unshil, C. Exploring the Lifelong Educational Meaning of the Inclusive Education in Laozi’s Tao Te Ching. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2020; 11, 647–662. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, H.G. The Philosophy of the Daodejing; Columbia University Press: New York, USA, 2007; pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Saussure. Course in General Linguistics; Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press: Beijing, China, 2001; pp. 136–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M. The Sankey Diagram in Energy and Material Flow Management: Part I: History. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2008, 1, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.Y. An Analysis of Hobbes' Philosophy of Language. Foreign Language Journal 2022, 4, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Introduction to Analytic Philosophy. Life·Reading·New Knowledge. Beijing: Sanlian Bookstore, China, 1999; pp.5-10.

- Wang, X.D. New Trends in Laozi Research. Academic Monthly 2017, 7, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.X. The Division and Common Characteristics of Schools of Pre-Qin Philosophy of Language. Foreign Language Journal 2010, 2, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus; Jiuzhou Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 484–490. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.Y.; Wu, G.Y. On the Philosophy of Language in LaoTze and Zhuangzi. Journal of Anhui University 2009, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. Study on the Thinking Paradigm of Laozi from the Perspective of Chinese Philosophy. Frontiers in Humanities and Social Sciences 2022, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Qin, H.; Liu, X.T. The Evolution and Development of Ecotranslatology Studies Based on the Analysis of CiteSpace Mapping Knowledge Domains. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2023, 10, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.C. The Philosophical Significance of the Debate between Names and Reality in Pre-Qin Philosophy of Language. Jiangxi Social Sciences 2006, 8, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.X.; Wang, X. Language, Thought and Reality: Syun Zih’s View of Language and Meaning and Its Modern Interpretation. Academic Exploration 2021, 8, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.K. Taoistic Psychology of Creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior 1996, 1, 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. The Advantages and Dilemmas of Chinese Scholars in the Study of Local Culture. Academic Circle 2017, 8, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.Y. The Unutteable Tao and the Artistic Conception Beyond the Image:Zhuangzi’s Philosophy of Language and its Effect on Artistic Conception Theory. Journal of Shandong Normal University 2007, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.N.; Liang, L.; Xu, D. Interpretation of Laozi’s Tao Thought on A Case of Depression. Theory and Practice of Psychological Counseling 2023, 5, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

|

①、②、③、④ Chapters 32, 25, 37, 41 of LaoTze

|

|

⑤、⑥、⑦ Chapters 81, 5, 45 of LaoTze

⑤、⑥、⑦ Chapters 81, 5, 45 of LaoTze

|

|

Chapter 28 of LaoTze

|

|

⑨ ⑩ Chapter 42, 12 of LaoTze

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).