Submitted:

13 November 2023

Posted:

14 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Leadership style as a protective factor against turnover intentions

1.2. Job Demands-Resourses model in relation to LMX theory

1.3. Work Adjustment Theory in relation to LMX Theory

1.4. The relationship between LMX and turnover mediated by Work Adjustment and Work Exhaustion

2. Research Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data analyses

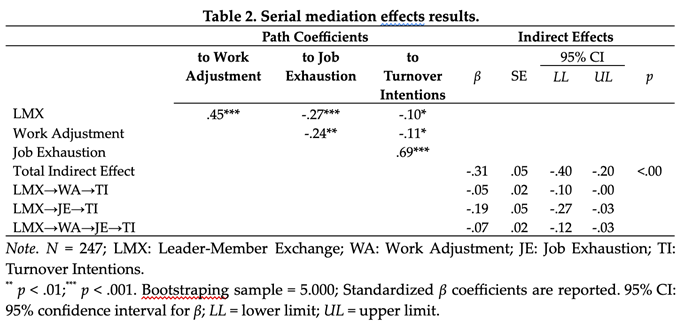

2.4. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions and practical implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giunchi, M.; Peña-Jimenez, M.; Petrilli, S. Work-Family Boundaries in the Digital Age: A Study in France on Technological Intrusion, Work-Family Conflict, and Stress. Med. Lav 2023, 114(4), e2023039. [CrossRef]

- Giunchi, M., & Vonthron, A. M. La relation entre l’usage professionnel des technologies numériques et l’addiction au travail médiatisée par les demandes psychologiques au travail: quelles différences entre les hommes et les femmes?. Psychol. du Trav. Organ. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dawis, R. V.; England, G. W.; Lofquist, L. H. A theory of work adjustment. Industrial Relations Center, 1964; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN.

- Dawis, R. V.; England, G. W.; Lofquist, L. H. A theory of work adjustment (a revision). Bulletin 1968 , 47(23). University of Minnesota: Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation.

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22(3), 309–328. [CrossRef]

- Al-Malki, M.; Juan, W. Leadership styles and job performance: A literature review. Int. J. Res. Mark 2018, 3(3), 40-49. [CrossRef]

- Padauleng, A. W.; Sidin, A. I.; Ansariadi, A. The relationship between leadership style and nurse’s work motivation with the implementation of patient safety culture in hospital, Bone regency. Enferm. Clin. 2020, 30, 161–164. [CrossRef]

- Amernic, J.; Craig, R.; Tourish, D. The charismatic leader as pedagogue, physician, architect, commander, and saint: Five master metaphors in Jack Welch’s letters to stock-holders of General Electric. Hum. Relat. 2007, 60, 1839-1872.

- Tourish, D. Challenging the transformational agenda: Leadership theory in transition?. Manag. Commun. Q. 2008, 21(4), 522-528. [CrossRef]

- Megawaty, M.; Hamdat, A.; Aida, N. Examining linkage leadership style, employee commitment, work motivation, work climate on satisfaction and performance. Hum. Resour. Manage. 2022, 2(1), 01-14. [CrossRef]

- Dansereau Jr, F.; Cashman, J.; Graen, G. Instrumentality theory and equity theory as complementary approaches in predicting the relationship of leadership and turnover among managers. J. Organ. Behav. and Hum. Perform. 1973, 10(2), 184-200. [CrossRef]

- Dansereau Jr, F.; Graen, G.; Haga, W. J. A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations: A longitudinal investigation of the role making process. J. Organ. Behav. and Hum. Perform. 1975, 13(1), 46-78. [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.; Cashman, J. F. A role-making model of leadership in formal organizations: A developmental approach. Front. in Leadership 1975, 143(165), 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. P.; Lee, G.; Carlson, K. D. An examination of the nature of the relationship between Leader-Member-Exchange (LMX) and turnover intent at different organizational levels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29(4), 591-597. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidou, O.; Vassilopoulou, J.; Groutsis, D. Flexible Working Arrangements, Ostracism and Inequality: The Role of LMX and Servant Leadership. Kucukaltan, B. (Ed.) Contemporary Approaches in Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: Strategic and Technological Perspectives. International Perspectives on Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 2023, Vol. 9, Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp. 171-192. [CrossRef]

- Gerstner, C. R.; Day, D. V. Meta-Analytic review of leader–member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82(6), 827-844. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; George, R. T. The relationship between leader-member exchange (LMX) and psychological empowerment: A quick casual restaurant employee correlation study. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29(4), 468-483. [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Nahrgang, J. D.; Morgeson, F. P. Leader-member exchange and citizenship behaviors: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92(1), 269-277. [CrossRef]

- Dunegan, K. J.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Duchon, D. LMX and Subordinate Performance: The Moderating Effects of Task Characteristics. J. Bus. Psychol. 2002, 17(2), 275-285. [CrossRef]

- Dienesch, R. M.; Liden, R. C. Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1986, 11(3), 618-634. [CrossRef]

- Deluga, R. J. Supervisor trust building, leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol 1994, 67(4), 315-326. [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R. W.; Hom, P. W.; Gaertner, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manage. 2000, 26(3), 463-488. [CrossRef]

- Harris, K. J.; Kacmar, K. M.; Witt, L. A. An examination of the curvilinear relationship between leader–member exchange and intent to turnover. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26(4), 363-378. [CrossRef]

- Morrow, P. C.; Suzuki, Y.; Crum, M. R.; Ruben, R.; Pautsch, G. The role of leader-member exchange in high turnover work environments. J. Manag. Psychol. 2005 , 20(8), 681-694. [CrossRef]

- Tangirala, S.; Green, S. G.; Ramanujam, R. In the shadow of the boss's boss: Effects of supervisors' upward exchange relationships on employees. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92(2), 309-320. [CrossRef]

- Maertz Jr, C. P.; Griffeth, R. W. Eight motivational forces and voluntary turnover: A theoretical synthesis with implications for research. J. Manage. 2004, 30(5), 667-683. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T. R.; Blader, S. L. The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 7(4), 349-361. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T. N.; Erdogan, B.; Liden, R. C.; Wayne, S. J. A longitudinal study of the moderating role of extraversion: Leader-member exchange, performance, and turnover during new executive development. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91(2), 298-310. [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, G. A.; Lehman, D. W.; Schoorman, F. D. Leader–member exchange and turnover before and after succession events. J. Organ. Behav. and Hum. Perform. 2010, 113(1), 25-36. [CrossRef]

- Meijman, T.F.; Mulder, G. Psychological aspects of workload, in Drenth, P.J.,Thierry, H. and de Wolff, C.J. (Eds), Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology,2nd ed.,Erlbaum, Hove, 1998. pp. 5-33.

- Schaufeli, W. B. Applying the job demands-resources model. A ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organ. Dyn. 2017, 2(46), 120-132. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Taris, T. W. A critical review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging occupational, organizational and public health. Bauer, G., Hammig, O, Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43-68.

- Giunchi, M.; Emanuel, F.; Chambel, M. J.; Ghislieri, C. Job insecurity, workload and job exhaustion in temporary agency workers (TAWs) Gender differences. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21(1), 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M. P. Early Predictors of Job Burnout and Engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93(3), 498-512. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, P. Impact of Burnout on Organizational Outcomes, the Influence of Legal Demands: The Case of Ecuadorian Physicians. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 662-662. [CrossRef]

- Swider, B. W.; Zimmerman, R. D. Born to burnout: a meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout, and work outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010. 76, 487–506. [CrossRef]

- Salama, W.; Abdou, A.H.; Mohamed, S.A.K.; Shehata, H.S. Impact of Work Stress and Job Burnout on Turnover Intention among Hotel Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9724-. [CrossRef]

- Rehder, K.; Adair, K. C.; Sexton, J. B. The science of health care worker burnout: Assessing and improving health care worker well-being. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2021, 145(9), 1095-1109. [CrossRef]

- Van Bogaert, P.; Clarke, S.; Willems, R.; Mondelaers, M. Nurse practice environment, workload, burnout, job outcomes, and quality of care in psychiatric hospitals: a structural equation model approach. J. Adv. Nurs 2013. 69, 1515–1524. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Bakker, A. B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J Organ. Behav. 2004, 25(3), 293–315. [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, A. D.; Keegel, T.; Shann, C.; D'Souza, R. An integrated approach to workplace mental health: an Australian feasibility study. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2014, 16(4), 205-215. [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K.; Gayed, A.; Bryan, B. T.; Deady, M.; Madan, I.; Savic, A. The importance of manager support for the mental health and well-being of ambulance personnel. PLoS ONE 2018, 13(5), e0197802. [CrossRef]

- Song, N. C.; Lee, H. S.; Lee, K. E. The Factors (Job Burnout, Job Engagement, the Workplace Safety) Influencing Employees' Job Satisfaction in School Food Service Operations. KJCN 2007, 12(5), 606-616. [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N. K.; Haslam, S. A.; Kerschreiter, R.; Schuh, S. C.; van Dick, R. (2014). Leaders enhance group members' work engagement and reduce their burnout by crafting social identity. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 28(1-2), 173-194. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. J.; Song, H. J. Determinants of turnover intention of social workers: Effects of emotional labor and organizational trust. Public. Pers. Manage. 2017, 46(1), 41–65. [CrossRef]

- Fukui, S.; Wu, W.; Salyers, M. P. Impact of Supervisory Support on Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Burnout and Job Satisfaction in a Longitudinal Study. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2019 , 46(4), 488-497. [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, H. F. Special Issue on the Theory of Work Adjustment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1993, 43(1), 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Dawis, R. V.; Lofquist, L. H. A psychological theory of work adjustment: An individual difference model and its applications. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. Borman, WC, Ilgen, DR, & Klimoski, RJ (2003). Handbook of Psychology, 12, 1984, pp. 132-133.

- Eggerth, D. E. From Theory of Work Adjustment to Person–Environment Correspondence Counseling: Vocational Psychology as Positive Psychology. J. Career Assess. 2008, 16(1), 60-74. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sangalang, P. J. Work adjustment and job satisfaction of Filipino immigrant employees in Canada. Revue canadienne des sciences de l'administration 2005, 22(3), 243-254. [CrossRef]

- Na-Nan, K.; Pukkeeree, P. Influence of job characteristics and job satisfaction effect work adjustment for entering labor market of new graduates in Thailand. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2013, 4(2), 95-103.

- Amarneh, S.; Raza, A.; Matloob, S.; Alharbi, R. K.; Abbasi, M. A. The Influence of Person-Environment Fit on the Turnover Intention of Nurses in Jordan: The Moderating Effect of Psychological Empowerment. J. Res. Nurs. 2021, 6688603. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ran, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yao, H.; Zhu, S.; Tan, X. Moderating role of job satisfaction on turnover intention and burnout among workers in primary care institutions: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19(1), 1526-1526. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, J. Exploring Explanatory Mechanisms of Adjustment-Specific Resources Underlying the Relationship between Leader–Member Exchange and Work Engagement: A Lens of Conservation of Resources Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15(2), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chathoth, P. K.; Chon, K. (2012). Measuring employees’ assimilation-specific adjustment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021 , 39(4), 1968-1994. [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Gruman, J.A. Socialization resources theory and newcomers’ work engagement: A new pathway to newcomer socialization. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 12–32. [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Ketprapakorn, N. Toward a theory of corporate sustainability: A theoretical integration and exploration. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122292. [CrossRef]

- Graen, G. B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6(2), 219–247. [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.G.; Curcuruto, M.; Matic, M.; Sciacovelli, P.; Toderi, S. Can Leader–Member Exchange Contribute to Safety Performance in An Italian Warehouse? Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 729–738.

- van Zoonen, W.; Sivunen, A.; Blomqvist, K.; Olsson, T.; Ropponen, A.; Henttonen, K.; Vartiainen, M. Factors influencing adjustment to remote work: Employees’ initial responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18(13), 6966. [CrossRef]

- C. Maslach, S.E. Jackson, & M.P Leiter (Eds.), Maslach Burnout Inventory.Manual (3rd ed., pp. 19-26). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Taris, T. W.; Schreurs, P. J. G.; Schaufeli, W. B. Construct validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey: A two-sample examination of its factor structure and correlates. Work & Stress 1999, 13(3), 223–237. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, I.; Santoro, P.E.; Fiorilli, C. A new tool to evaluate burnout: the Italian version of the BAT for Italian healthcare workers. BMC Public Health 2022 22, 474. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand F.; Peters S.; Pérée F.; Hansez I. Facteurs d’insatisfaction incitant au départ et intention de quitter le travail: analyse comparative des groupes d’âges [Factors of dissatisfaction encouraging resignation and intention to resign: a comparative analysis of age groups]. Trav. Hum 2010, 73, 213–237. [CrossRef]

- Behling, O.; Law, K.S. Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments: Problems and Solutions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000.

- Muthén, L. K.; Muthén, B. O. 1998–2012. Mplus user’s guide (version 7). Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen. Los Angeles, CA.

- Yuan, K. H.; Chan, W.; Marcoulides, G. A.; Bentler, P. M. Assessing structural equation models by equivalence testing with adjusted fit indexes. Structural Equation Modeling: J. Multidiscip. Res. 2016, 23(3), 319-330.

- Podsakoff, P. M.; MacKenzie, S. B.; Lee, J. Y.; Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psycho 2003, 88(5), 879. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Ismail, W. K. W.; Amin, S. M.; Ramzan, M. Influence of relationship of POS, LMX and organizational commitment on turnover intention. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 31(1), 55-68.

- Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C. Organizations and supervisors as sources of support and targets of commitment: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24(3), 251-270. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Eldridge, D. The missing link in newcomer adjustment: The role of perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2011 , 19(1), 71-88. [CrossRef]

- Adil, M. S.; Baig, M. Impact of job demands-resources model on burnout and employee's well-being: Evidence from the pharmaceutical organisations of Karachi. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2018, 30(2), 119-133. [CrossRef]

- Joo, B. K. Organizational commitment for knowledge workers: The roles of perceived organizational learning culture, leader–member exchange quality, and turnover intention. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2010, 21(1), 69-85. [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, S.; Sathiyaseelan, A. Relationship based leadership: The development of leader member exchange theory. RJSSM 2016, 5(11), 165-171. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Relationship among leader-member exchange (LMX), burnout and career turnover intention in social workers using SEM. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society 2013, 14(8), 3739-3747. [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B. E.; Sluss, D. M.; Harrison, S. H. Socialization in organizational contexts. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2007 22, 1-70. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xu, X. A.; Li, J. Exploring Explanatory Mechanisms of Adjustment-Specific Resources Underlying the Relationship between Leader–Member Exchange and Work Engagement: A Lens of Conservation of Resources Theory. Sustainability 2023, 15(2), 1561. [CrossRef]

- Luksyte, A.; Bauer, T. N.; Debus, M. E.; Erdogan, B.; Wu, C. H. Perceived overqualification and collectivism orientation: Implications for work and nonwork outcomes. J. Manage. 2022, 48(2), 319–349. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; He, P.; Jiang, C. How and when does socially responsible HRM affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169(2), 371–385. [CrossRef]

- Boon, C.; Biron, M. Temporal issues in person–organization fit, person–job fit and turnover: The role of leader–member exchange. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69(12), 2177–2200. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Wu, F.; Liu, M.; Tang, G.; Cai, Y.; Jia, H. How leader-member exchange influences person-organization fit: a social exchange perspective. Asian Bus. Manag. 2023, 22(2), 792-827. [CrossRef]

- Raghuram, S.; Garud, R.; Wiesenfeld, B.; Gupta, V. Factors contributing to virtual work adjustment. J. Manage. 2001, 27(3), 383-405. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; van Veldhoven, M. J. P. M.; Xanthopoulou, D. Beyond the demand-control model: Thriving on high job demands and resources. J. Pers. Psychol. 2010, 9(1), 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H. J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. M.; Bakker, A. B., Bipp, T.; Verhagen, M. A. Individual job redesign: Job crafting interventions in healthcare. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 104, 98-114. [CrossRef]

- Ripamonti, S. C.; Galuppo, L.; Petrilli, S., Dentali, S.; Zuffo, R. G. Care ethics management and redesign organization in the new normal. Front.Psychol. 2021, 12, 747617. [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J. Employees seek personal value and purpose at work. Be prepared to deliver. Gartner. Com. Retrieved January 2022, 13.

- Huang, I. C.; Du, P. L.; Wu, L. F.; Achyldurdyyeva, J.; Wu, L. C.; Lin, C. S. Leader–member exchange, employee turnover intention and presenteeism: the mediating role of perceived organizational support. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42(2), 249-264. [CrossRef]

- Falkenburg, K.; Schyns, B. Work satisfaction, organizational commitment and withdrawal behaviours. Manag. Res. News 2007, 30(10), 708-723. [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, A. H. Investigating factors that influence employees' turnover intention: A review of existing empirical works. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10(12), 152. [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | - | ||||||

| 2. Age | 46.09 | 12.46 | -.21*** | - | |||||

| 3. Work Mode | - | - | .03 | -.16* | - | ||||

| 4. LMX | 3.32 | .90 | -.01 | .07 | .19** | (.91) | |||

| 5. Work Adjustment | 3.54 | .87 | -.08 | .06 | .28*** | .45*** | (.86) | ||

| 6. Job Exhaustion | 3.38 | 1.50 | .08 | -.08 | -.05 | -.38*** | -.36*** | (.92) | |

| 7. Turnover Intention | 2.11 | .77 | .14* | -.05 | -.07 | -.41*** | -.40*** | .77*** | (.91) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).