1. Introduction

Student learning is a multi-faceted concept and many studies have investigated this issue from the following perspectives: the relationships among student learning, student engagement, and technology [

1], gender disparity [

2], and teachers’ instructions and feedback [

3]. As universities offered various programs and access to students, it has been a constant search to find a way to enhance student learning. Previous research also found that students who play an active role in the decision-making process might increase their ownership of the learning outcomes [

4,

5,

6]. Students would be more invested in their learning if they were the ones choosing their academic journey. Such educational practice creates an opportunity for undergraduates to choose and be responsible for their academic journey. Traditionally, college students were placed into courses; however, the directed self-placement policy has offered students to play a more active role in their learning.

In 2017, California State University (CSU) issued Executive Order 1110, which revised the policy for first-year student placement in writing and quantitative reasoning courses. Complying with Executive Order 1110, San José State University (SJSU) has implemented Directed Self-Placement (DSP) in writing courses. Before DSP’s implementation, students were placed into courses via placement exams, Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT) scores, and college-equivalent courses taken before entering SJSU. After the academic year 2016, students have been placing themselves in their first-year writing courses via the DSP process [

7]. The DSP process at SJSU incorporates five modules including reading essays, writing exercises, and surveys that allow students to explore how they are as readers and writers. By doing so, DSP empowers students to choose the First-Year Writing Program (FYW) course that best meets their needs. Through the DSP process, students choose courses based on their prior learning experiences and learning needs.

Psychological factors influence how students acquire new knowledge and skill, perceive their own learning, academic performance, and motivation [

8,

9]. Psychological factors such as higher levels of confidence and satisfaction can promote the academic ability for high school students [

10]. As students need to complete their writing and reading surveys before choosing their FYW course and then another learning satisfaction survey after the class, such survey might provide a glimpse of how psychological factors affect their learning. The collected survey data might provide us an opportunity to explore how undergraduates choose their academic journey based on their prior learning experiences and psychological factors. Then, how those aforementioned factors affect their chosen academic journey in the FYW program. It also informs who are the students in the First-Year Writing program and whether their academic journey diverged. Finally, it might suggest factors other than prior learning experience as well as psychological factors that truly affect students’ academic journey.

2. Literature Review

2.1. First-Year Writing Programs & Undergraduate Learning

FYW or first-year writing courses (FYC) have long served as an introductory experience for freshmen, regardless of location or institution type [

11]. The common goals of FYW programs including transitioning students from high school to college-level courses [

12], instilling confidence in and preparing to become capable writers and helping students realize their potential as writers and critical thinkers [

13]. It is important to note that while these FYW programs share similar goals, each institution designs its curriculum differently.

Research also showed that FYW courses could foster student retention [

14] as well as be instrumental in developing literacy skills such as description, discussion, and reflection. FYW courses also help students transition into college-level courses by developing habits of mind and practicing college-level research writing. It is worth mentioning that these courses tend to have capped enrollment and smaller class sizes to allow for in-class discussion, small group work, and peer review. It has been shown that these practices enhance peer connection and student-faculty interaction, both of which likely contribute to student retention [

15].

FYW also develops metacognitive awareness as students develop their sense of responsibility for and ownership of their learning outcome [

16]. The writing process built into the FYW curriculum – drafting, writing, revising, and reflecting - fosters metacognition, or how students self-regulate and monitor their learning [

17]. The development of metacognition could lead not only to improve writing skills but could also contribute to postsecondary education outcomes [

18]. At SUSU, students are first asked to explore themselves as readers and writers through the Reflection on College Writing [

19] before their FYW courses. The goal of this online course is to facilitate student learning by the following steps:

Students reflect on their literacy journey and prior learning experience.

Survey their level of comfort and confidence in writing and reading.

Understand available FYW course options

Choose their writing FYW course

Share why they choose the course with their future FYW instructors

After completing the course, students complete exit survey to report their learning experience and satisfaction.

2.2. Reflection of College Writing & Undergraduate Learning

Previous studies found that developing autonomy during college years prepares students for future employment by making decisions and owning the consequences of decisions [

20,

21]. Although providing choices might empower students and potentially prepare them for the future workforce, they might not be able to make sound decisions based on short-sighted interests. Students could make choices that might decrease their initial but increase their long-term expense [

22]. By exploring factors related to students’ chosen academic journey, this study could identify such factors and promote student learning.

Psychological factors have been found to affect student learning. For example, students’ stress level affects their intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among freshmen in Psychology class [

23]. For example, psychological factors related to psychological problems such as stress level might also affect teaching and learning [

24]. They found that fast-paced online English language teaching could result in stress both on teachers and students and affect the effectiveness of teaching and learning. Students prefer less stressful online interactions with their peers and teachers [

25]. These studies suggested that decreasing levels of stress and increasing comfort might be an important factor in promoting the success of online learning environment.

Besides the abovementioned psychological factors, students who left their prior learning environment which shapes their overall learning experience can also affect their learning. Leaving environment might cause psychological discomfort such as anxiety, loneliness, irritability, and discomfort [

26]. The environment can also refer to students’ prior learning environment or how it affected their learning experience. Other factors could also suggest how well students adjusted their learning environment. For example, if a student is highly satisfied with their learning experience, they would recommend others or would choose the same academic journey again [

27]. The high level of student satisfaction suggests the learning environment might be more inclusive and ease the transition. Another study also found that 36% of undergraduates reported their learning cognition during online education [

28].

2.3. Theoretical Framework & Research Questions

Metacognition has been found indispensable to independent learning and development [

29]. Students immerse themselves in Reflection of College Writing (RCW) and explore how they are as writers. Students employ their metacognitive skills by reflecting on and ultimately assessing their performance to determine which course would best help them learn. In RCW, students reflected on their literacy narratives in the first module and then explore their writing/reading comfort and confidence in the subsequent modules. After that, students chose their preferred writing course based on the learning experience from the previous three modules. After students completed RCW, which is the online module before the actual writing course, they chose and enrolled in their own writing course. After completing the writing course, they also filled out an exit survey to assess their writing and learning experience in class.

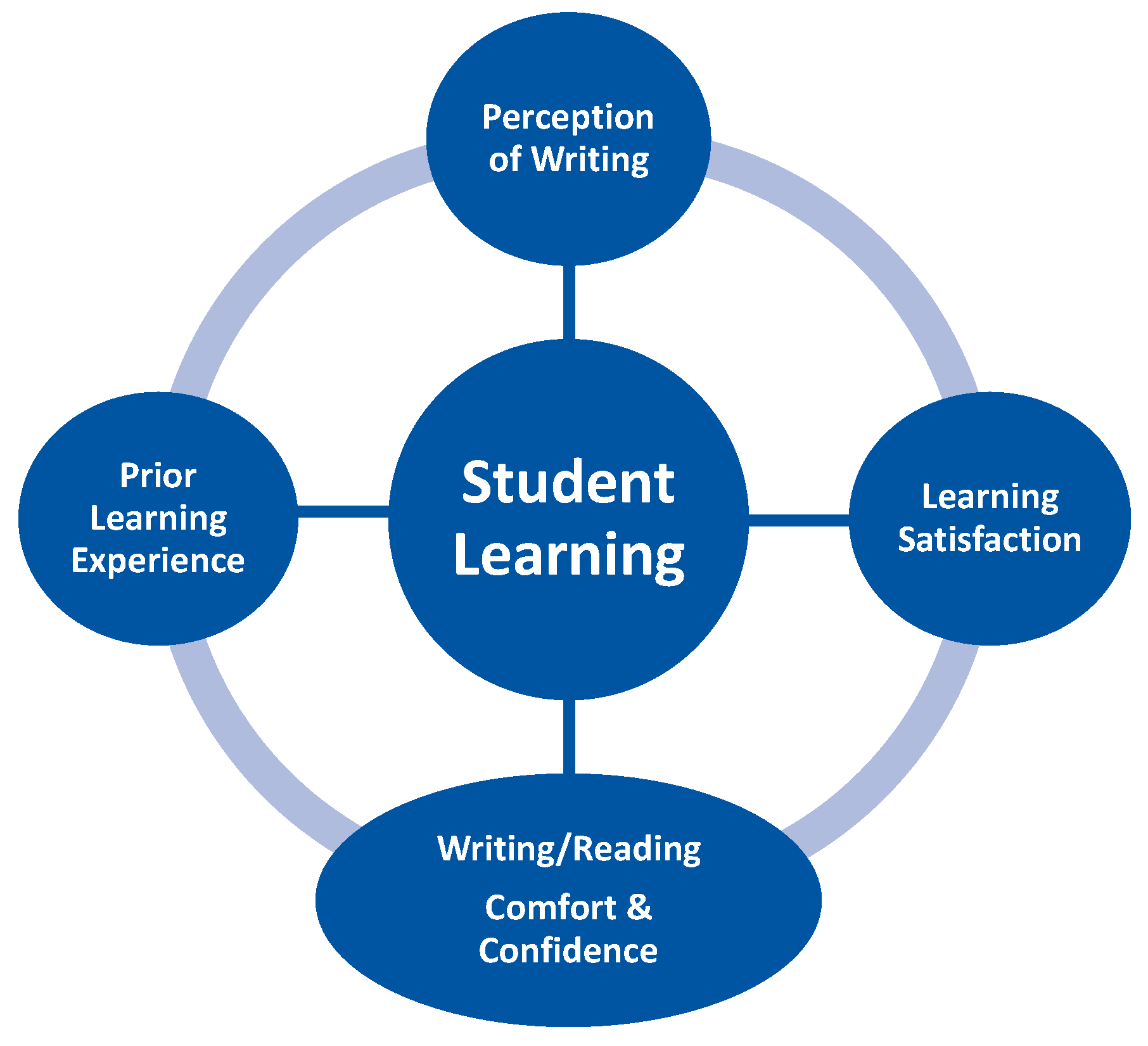

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of this study is hypothesized student learning is related to prior learning experience, students’ perception of writing, reading/writing comfort and confidence, and finally learning satisfaction.

Previous studies found that writing comfort, writing confidence, reading comfort, and reading confidence contribute to student learning [

30]. As such, this study continues to explore whether these aforementioned factors have a causal relationship with student learning. Prior learning experiences in this study include students’ high school Grade Point Average (GPA) as well as their writing experience before college. As for perception of writing, it refers to whether students perceived themselves as strong writers after completing their first-year writing course. Learning satisfaction in this study refers to whether students would enroll in the same course again.

2.4. Research Questions

Students reflect on who they are as readers and writers while unpacking their college writing requirements through their prerequisite writing course, which is RCW. Once they have completed the RCW, they can choose their first-year writing course. In this study, we examine how prior learning experiences affect their FYW program learning experience in general. We then explore how psychological factors affect their learning in the FYW program through different courses. It also intends to explore how students’ perceptions of themselves as writers related to their FYW program learning. Ultimately, this study aims to answer the following questions:

How is students’ overall learning in the FYW program?

To what extent do prior learning experiences influence students’ course choices?

To what extent, do prior learning experiences, perception of writing, writing/reading comfort and confidence affect student learning?

3. Method

This study aims to explore how psychological factors influence student learning by using FYW program data. We first explore who are the FYW program students, including their prior academic backgrounds and demographics. We then examine student learning experience in the FYW program. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the purpose of our study and our methods of collecting data. Excel and Tableau were used to clean and recode the data. Tableau and SPSS were used to conduct data analysis for this study. This data contains 5 survey datasets and students’ grade data. The following section describes the terminology, data collection and analysis procedure.

3.1. Definition

Writing comfort and writing confidence were measured by using a 10-item survey to assess students’ perceptions of their writing ability. Both of these two surveys have an almost strong reliability index based on this current sampling population. The reliability for the reading survey was .6 while .73 for the writing one; thus, suggesting the overall consistency of both surveys. Thus, we considered using these two surveys to report out students’ level of comfort and confidence. Students evaluated themselves on a scale from 1 to 4 on which 4 representing a higher level while 1 representing a lower level of comfort and confidence.

3.2. Reading Comfort

The total scores for reading comfort ranged from 0 to 12; we discovered that 75% of students scored in the range from 8 to 10. Reading comfort represents the cumulative results from the following three survey items:

I was able to find a comfortable reading pace to read and understand both samples.

I did not strain to keep pace with the sentence length or complexity in Sample A

Sentences in Sample B slowed me down, but I was able to adjust and maintain a comfortable reading pace.

3.3. Writing Comfort

The total scores for writing comfort ranged from 0 to 16; 67% of students scored from 10 to 13. Writing comfort was determined using the composite scores of the following four items:

I easily located examples from my reading to formulate my own ideas about college writing.

I felt comfortable composing this essay to present in a classroom work, to a real audience that includes my fall writing instructor.

I would feel comfortable participating in a workshop of this draft, giving advice on my peers’ drafts and asking for their advice on my draft.

I completed this assignment within the suggested time frame.

3.4. Reading Confidence

The total scores for reading confidence ranged from 7 to 28; we determined 73% of students scored in the range of 17 to 22. Reading confidence contains the total scores of the following seven items:

Sample B was harder for me to read than sample A, but I feel confident that I could finish the reading in a single study period.

I will feel confident participating in a class discussion of either or both samples.

I feel confident to quote from, summarize, and respond to Professor Sommer’s essays in writing.

To feel confident about my understanding of the meaning in these essays, I would need time to look up words. But I would feel confident doing so without direction from a tutor or instructor.

I could complete both of these reading assignments in a single week, along with the other work I will have scheduled, in class and out of class, this fall.

I could complete both of these assignments independently, without the help of a tutor or friends.

After experiencing this reading assignment, I feel prepared for the demands of college reading.

3.5. Writing Confidence

The total scores for writing confidence ranged from 0 to 20 with 63% of students scoring in the range of 13 to 16. Writing confidence contains the combined scores of the following 5 items:

The single, brief prewriting exercise was enough for me to confidently draft evidence and ideas for my readers.

I am confident that I effectively integrated examples from my reading into my writing to convincingly illustrate my definition and estimation of college writing and its demands.

I felt confident using the lessons I learned in high school writing courses to complete this college writing assignment.

With classroom instruction alone, I feel I could be successful in a course that required me to write, revise, and edit six to eight such integrated reading and writing assignments in a single semester.

After completing this college writing assignment, I feel confident that I am prepared to meet the challenges of college writing.

3.6. Data Collection

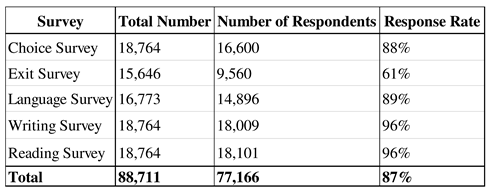

The five survey datasets have been collected via different approaches since the inception of this study. The surveys were collected via three methods from 2015 to 2021: paper survey, Qualtrics, and Canvas. The exit survey, for example, has been completed by freshmen who completed either ENGL 1A or Stretch from the AY 2015 to 2021. If students did not enroll in either of those courses then they do not receive the invitation to complete the exit survey. The survey was first conducted as an in-class paper survey (Fall 2015-Spring 2016), before we switched to Qualtrics (Fall 2016 to Spring 2020), and then finally to Canvas (AY 2020-2021). Choice, Writing, and Reading surveys were distributed via Canvas to all freshmen who enrolled in RCW at SJSU. The number of survey respondents by the survey is shown in

Table 1.

3.7. Data Analysis

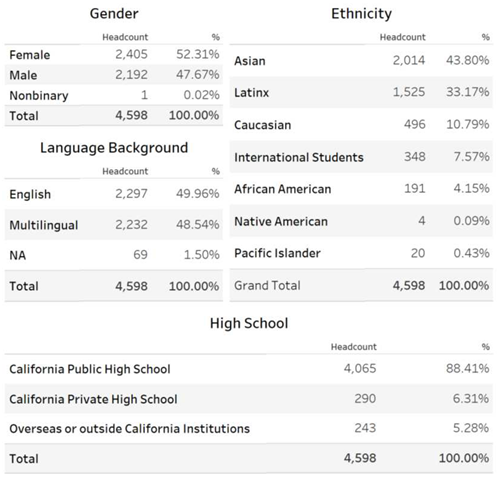

The data analysis of this study is separated into descriptive statistics and regression analysis. The total number of descriptive statistics is varied by the number of survey participants who responded to the items or the actual number of students who received a letter grade at the end of the class. Thus, the total number of each item as well as the academic outcomes by courses would be different. For example, the total number of students who completed a two-semester course is 1,844 for a yearlong course and 8,841 for a semester long course. Among all those students who completed the course, 4,598 students completed all 5 survey and that is the sample size for regression analysis.

The regression analysis is applied to examine whether the underlying theoretical assumption regarding prior learning experience, perception of writing, and psychological factors such as confidence, comfort, and learning satisfaction influence student learning in the FYW writing program. In this study, we examine how well the predictors can explain the outcome variable: student learning. The predictors in the model are learning satisfaction, high school GPA, writing comfort, writing confidence, reading comfort, reading confidence, perception of the strong writer, and prior writing experience. The theoretical assumption of a such regression model is that these predictors can explain certain aspects of student learning among students in FYW programs at SJSU.

Table 2 displays the demographics of the data by headcounts and percentages.

4. Results

The result section is reported by course choice factors and student learning, psychological factors, and student learning— reading/writing comfort and confidence in the First-Year Writing program. Finally, this study explores how students’ perceived writing competency affects their learning.

4.1. Course Choice Factors & Learning

As part of the RCW (the requisite course for DSP at SJSU), students compose a paragraph to their FYW instructor explaining their course decision. In Sample 1, we see that the student has opted to take the single-semester ENGL 1A course based on their levels of comfort and confidence in prior English course experience. Because the student had kept pace in both AP English and various courses at their local community college, they feel prepared to navigate the faster-paced, semester-long writing course at SJSU.

Sample 1:

“In each of my essays you will notice a strong point in the work achieved. However, stated, my paragraphs in my essays do lack continuous growth and explanation. I believe that I could achieve the critical level of writing if I just apply myself to the time needed. After briefly and critically thinking upon the best choice for me to take within my college career, I have decided to choose English 1A.

In my first year of taking Advanced Placement and college courses within the San Jose city college community, I found myself being at a comfortable pace despite the challenges that came within. With learning ways of writing I applied them with practice throughout the year improving more as the days came. I believe that this course, with that being said, will help me to achieve the writer of great ability within the structured pace and learning management. I hope as the year progresses, my writing will too.”

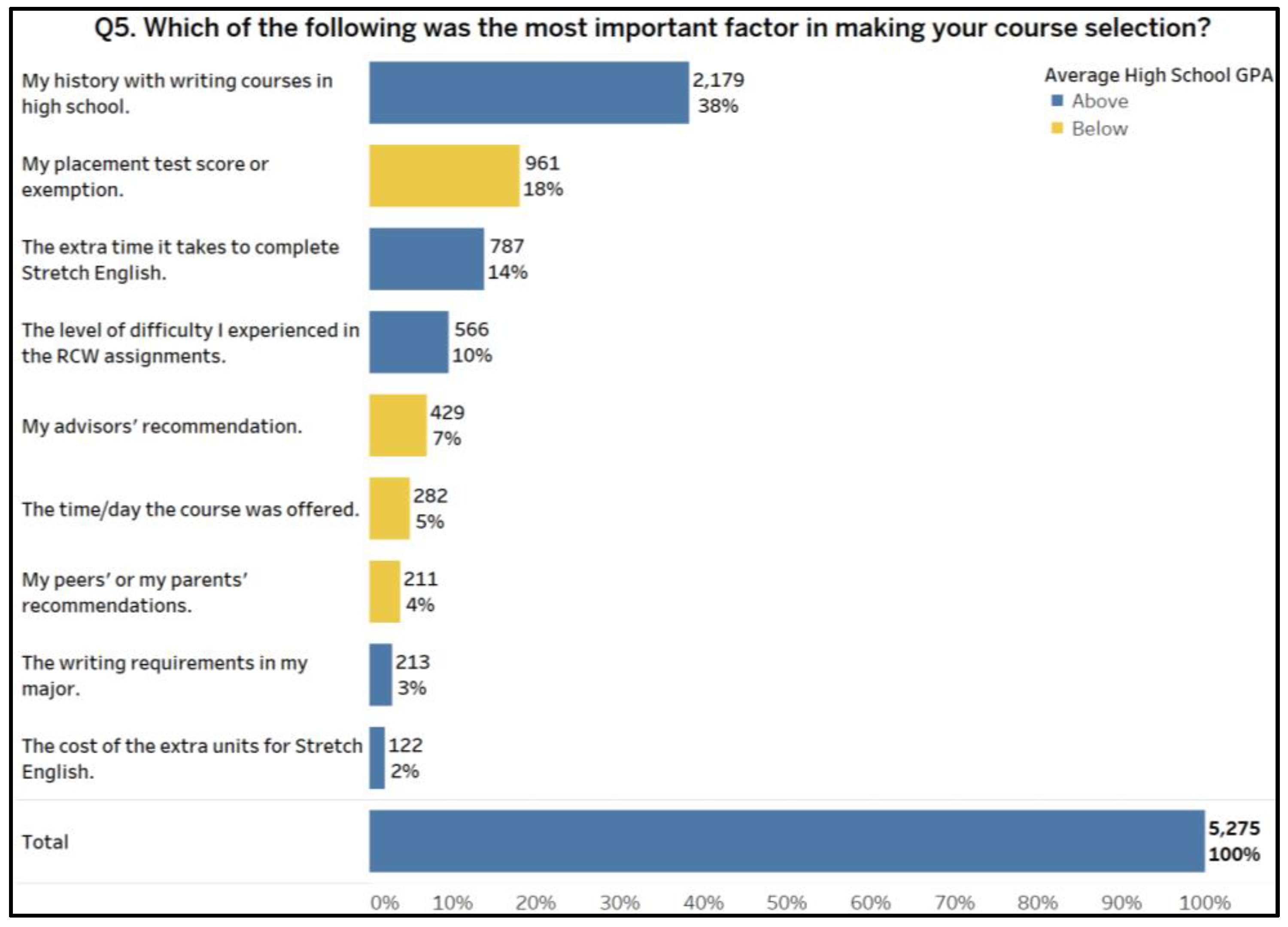

This sample illustrates how this student decided to choose their writing course. Sample 1 aligns with the results in

Figure 2 regarding how students rate the most important factor in making their course selection. The average high school GPA is 3.43. Students who had a below 3.43 GPA are highlighted in yellow while those who had a above 3.43 GPA are highlighted in blue.

These survey responses show that students’ prior learning experience—their history with writing course in high school was the most important factor in making course selection. Students also chose courses based on their placement tests and exemptions (e.g., AP course recognition); however, these factors played a far lesser role than their course histories. The results also reveal that students who chose Stretch found that the extra semester allowed them to have more time and space to improve their learning experience. The level of difficulty students experienced in the RCW assignments also helped them choose their courses. If they could finish assignments very quickly, they usually enrolled in ENGL 1A rather than Stretch. Finally, we learned that around 7% of students chose their writing course based on their advisor’s recommendation. The results showed that 66% of students chose their writing course based on their prior learning experience. We then further explored whether there are any differences in academic performance among those students with a different prior learning experience.

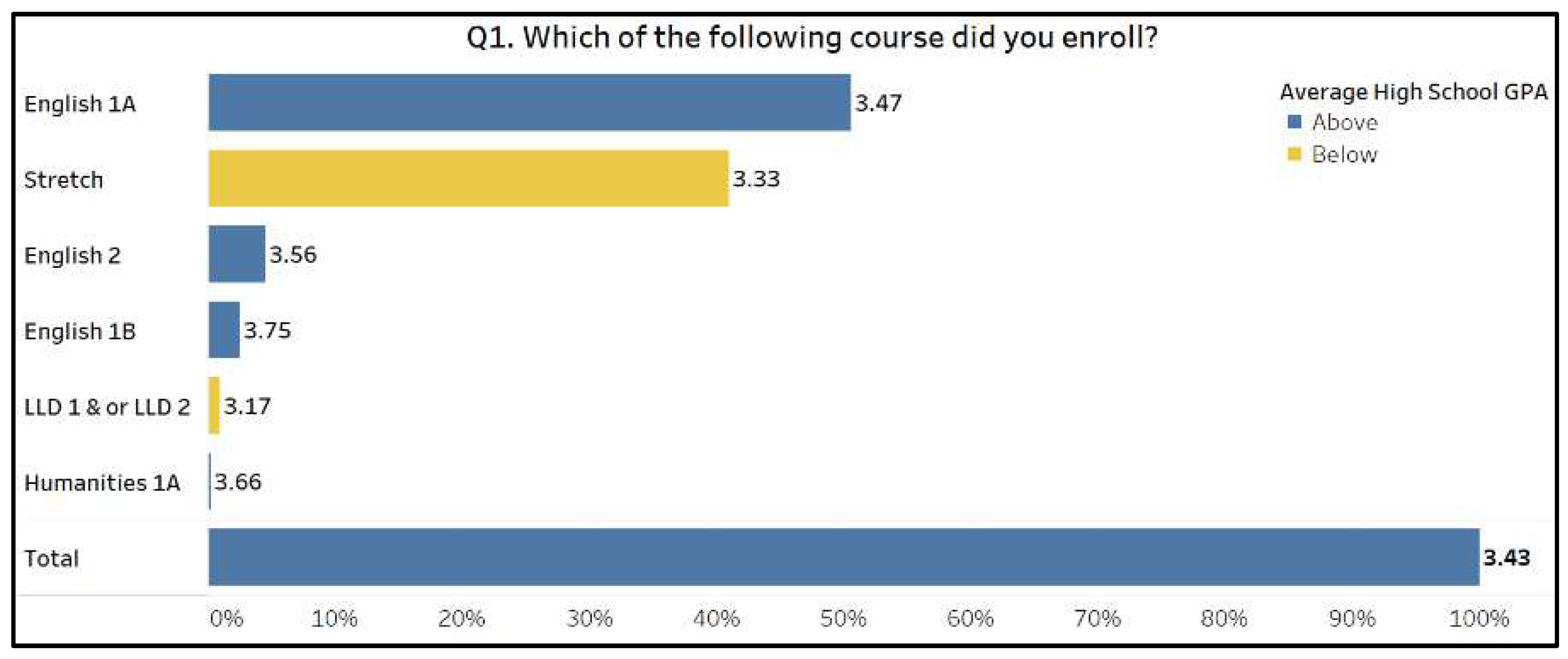

The following graph shows the extent to which SJSU freshmen chose their FYW courses based on their previous high school GPA. The course choice has been revised based on the available courses in 2016, at which point LLD 1 and LLD 2 were no longer available to SJSU students. Students were invited to join the Honors Program—Humanities 1A. The choice survey results showed that 87% of respondents had indeed enrolled in the course they had chosen. Thus,

Figure 3 is close to the actual enrollment but not exact as 13% of students changed their choices when enrolling in courses.

The majority of students who chose Stretch – as well as those who chose LLD 1 or LLD 2 - had a below-average high school GPA, while students who chose ENGL 1A had a slightly high school GPA compared to their peers. The results suggested that these students might not do as well as their peers did back in high school. However, these prior academic differences do not affect their academic performance in Stretch or ENGL 1A. The final grades of students within the following categories: Pass (A-C/CR), Fail (D-F, NC), Incomplete (I), Unauthorized Withdrawal (WU), and Withdrawal (W). The average course pass rate in the class is highlighted in the grey line. ENGL 1A was the default choice before implementing RCW. The result showed that students who had choice to enroll in ENGLA 1A had a higher pass rate compared to their peers who did not have that choice.

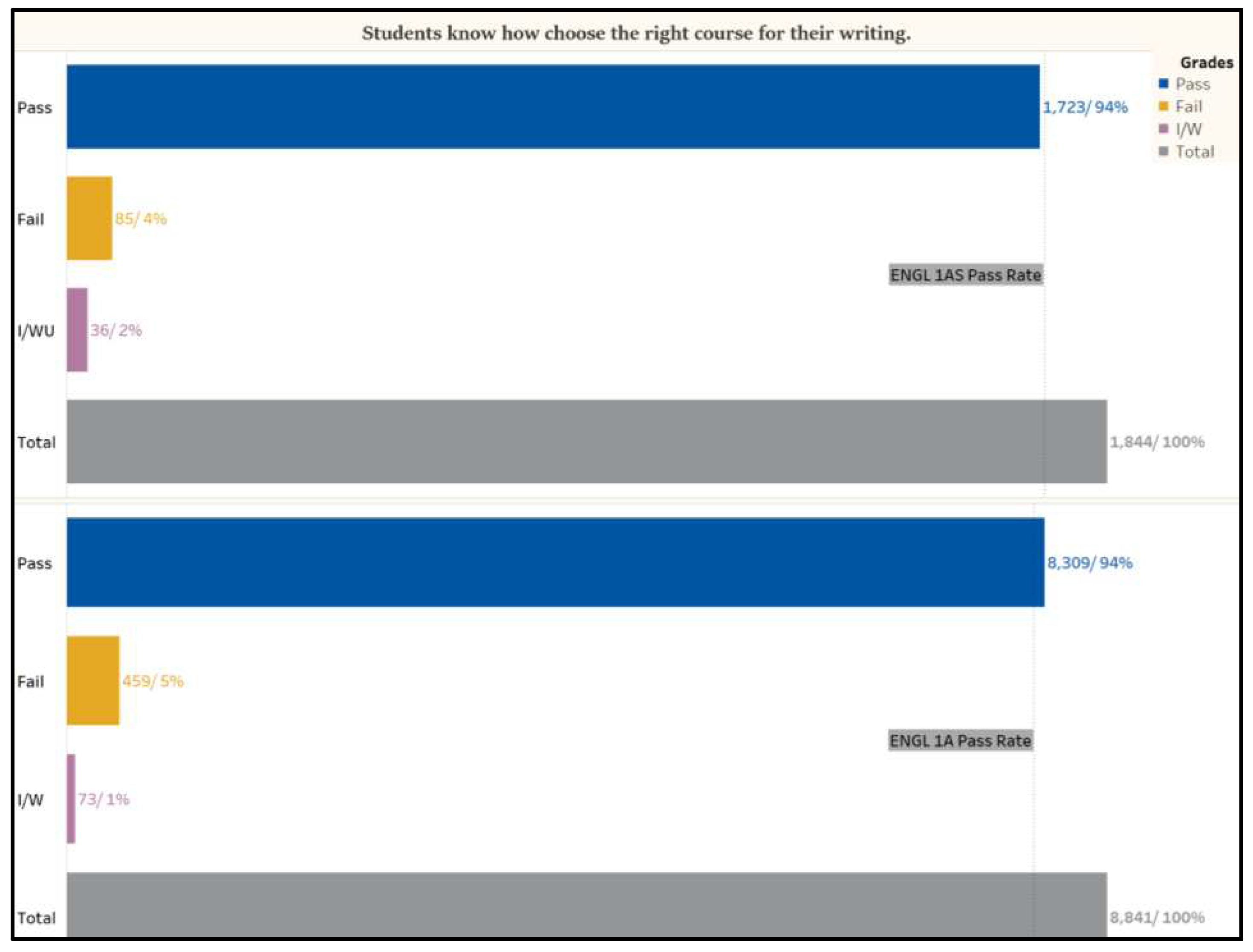

The results evidenced that the pass rates of students who chose Stretch versus ENGL 1A were virtually the same. The results suggest that students can determine their writing proficiency (at the time of placement) through RCW and place themselves in the course that best meets their needs. The results also showed that students’ high school GPAs had little impact on their FYW course outcomes. Although students who chose ENGL 1A had a higher high school GPA than those who chose Stretch, their pass rates in these two courses are the same at 94%.

4.2. Psychological Factors: Reading/Writing Comfort and Confidence

In the paragraph to their FYW instructors, many students indicated they chose Stretch English to allow them more time to work through readings, activities, and major assignments. This decision was often directly related to their level of comfort and confidence. In Sample 2, we see one student’s desire to “get used to college writing” at “a comfortable pace.” The student has already identified areas in which they hoped to improve (e.g., essay length, organization, and clarity), which suggests an awareness of their strengths and weaknesses. They seek to improve their writing – and gain comfort and confidence as writers – by taking the course that allows them to have more time and space to improve their writing.

Sample 2:

“I am so excited to be in your Stretch English class in the Fall Semester! I chose to take the Stretch English class because I feel that I am not a strong writer when it comes to long essays or essays that have a broad topic. And from the reading that I have done, college essays seem to consist of at least 3-4 pages. I think that this course would be the right one for me because having that extra time would allow me to get used to college writing at a comfortable pace. I believe that taking this course would help me to develop as a writer at SJSU by helping me improve at conveying my thoughts onto my writings in an organized way and to also write long essays that are easy for the reader to understand.”

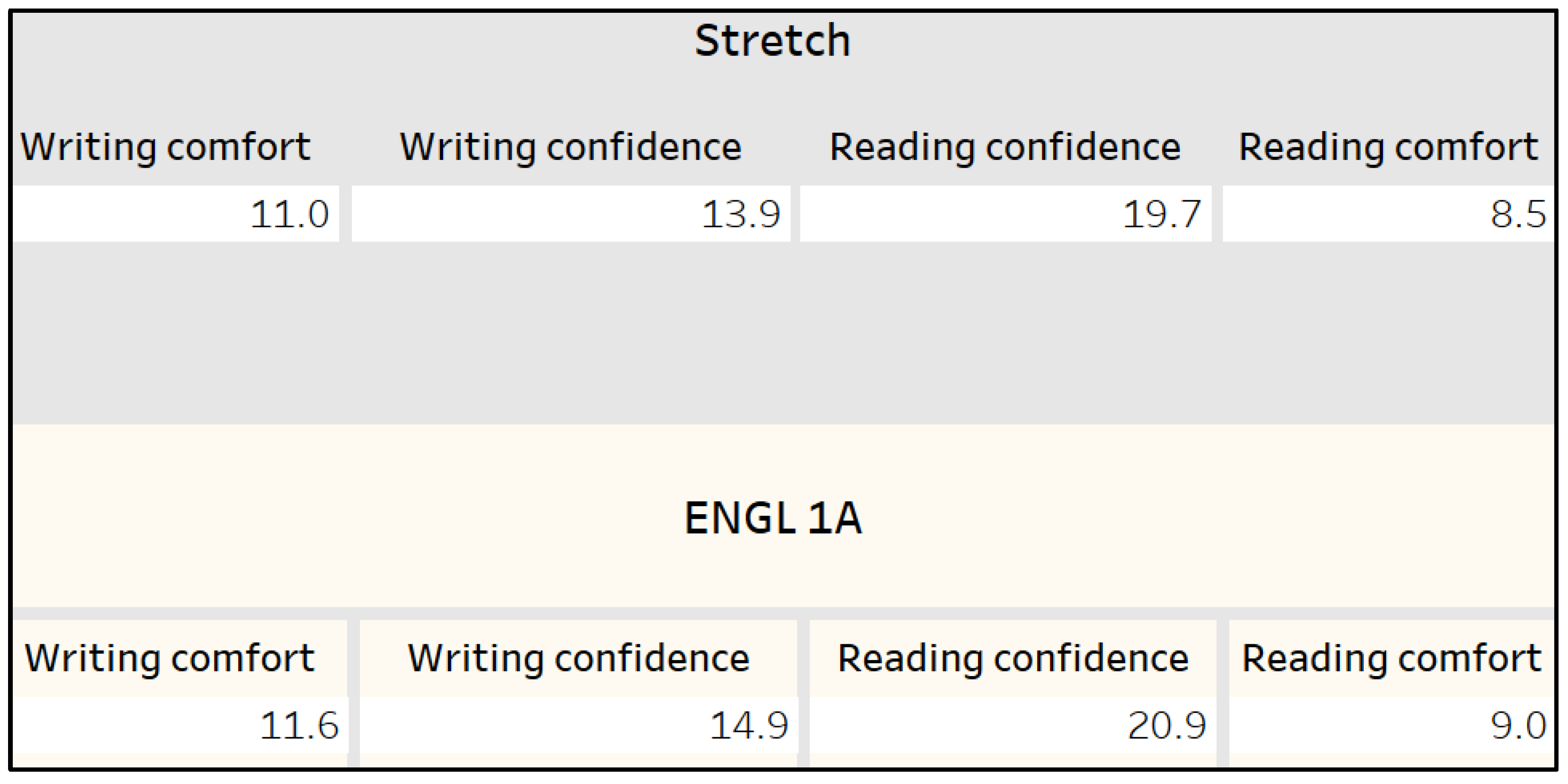

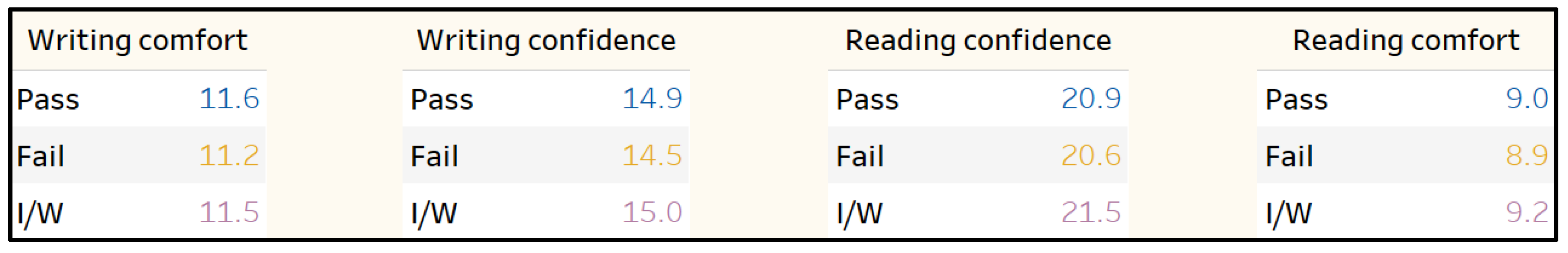

Comfort and confidence in both reading and writing are shown through the average scores of students in a given class. Here, we have broken the scores up into two courses: two-semester Stretch and one-semester ENGL 1A.

Figure 5.

Average reading/writing comfort and confidence by courses.

Figure 5.

Average reading/writing comfort and confidence by courses.

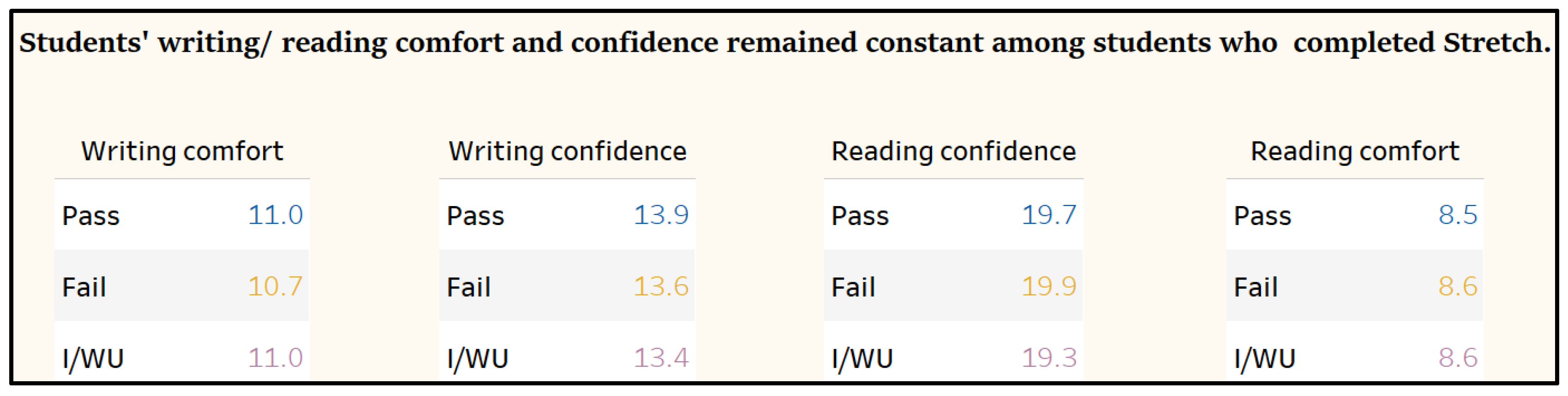

On average, students enrolled in ENGL 1A scored themselves higher in reading/writing comfort and confidence compared to their peers enrolled in Stretch. This result suggests that students who enrolled in ENGL 1A had placed themselves into the single semester course because they had a higher level of confidence in reading and writing. However, the level of writing/reading comfort and confidence do not appear to be directly related to academic outcomes, as shown in the following figure—

Figure 6.

The higher levels of writing/reading comfort and confidence cannot predict whether students would complete the course they had chosen. For example, students who either failed to complete or withdrew from ENGL 1A had higher “writing confidence” compared to their peers who passed. Similarly, students who did not complete or withdrew from ENGL 1A tended to also have higher “reading comfort” compared to their peers who passed. The results suggested that higher levels of psychological factors such as reading confidence could not predict whether students could complete the courses. Here we also see that students who completed Stretch had slightly different results compared to their peers in ENGL 1A.

These results demonstrated that students who completed Stretch had similar levels of reading/writing comfort and confidence, regardless of their grades. The results showed that students’ final Stretch grades had little to do with their prior reading/writing comfort and confidence before the Stretch class.

4.3. Students’ perception as a good writer or reader

This course gave me the support I needed, but also challenged my skills as well.

-Students’ comments on Spring 2020 Exit Survey

At the end of the writing class, students were surveyed to ascertain whether the class had made them a “strong” writer. Students were prompted to respond with a “yes” or “no.” We have shown the results by two different courses. These responses are also highlighted by academic outcomes as shown in

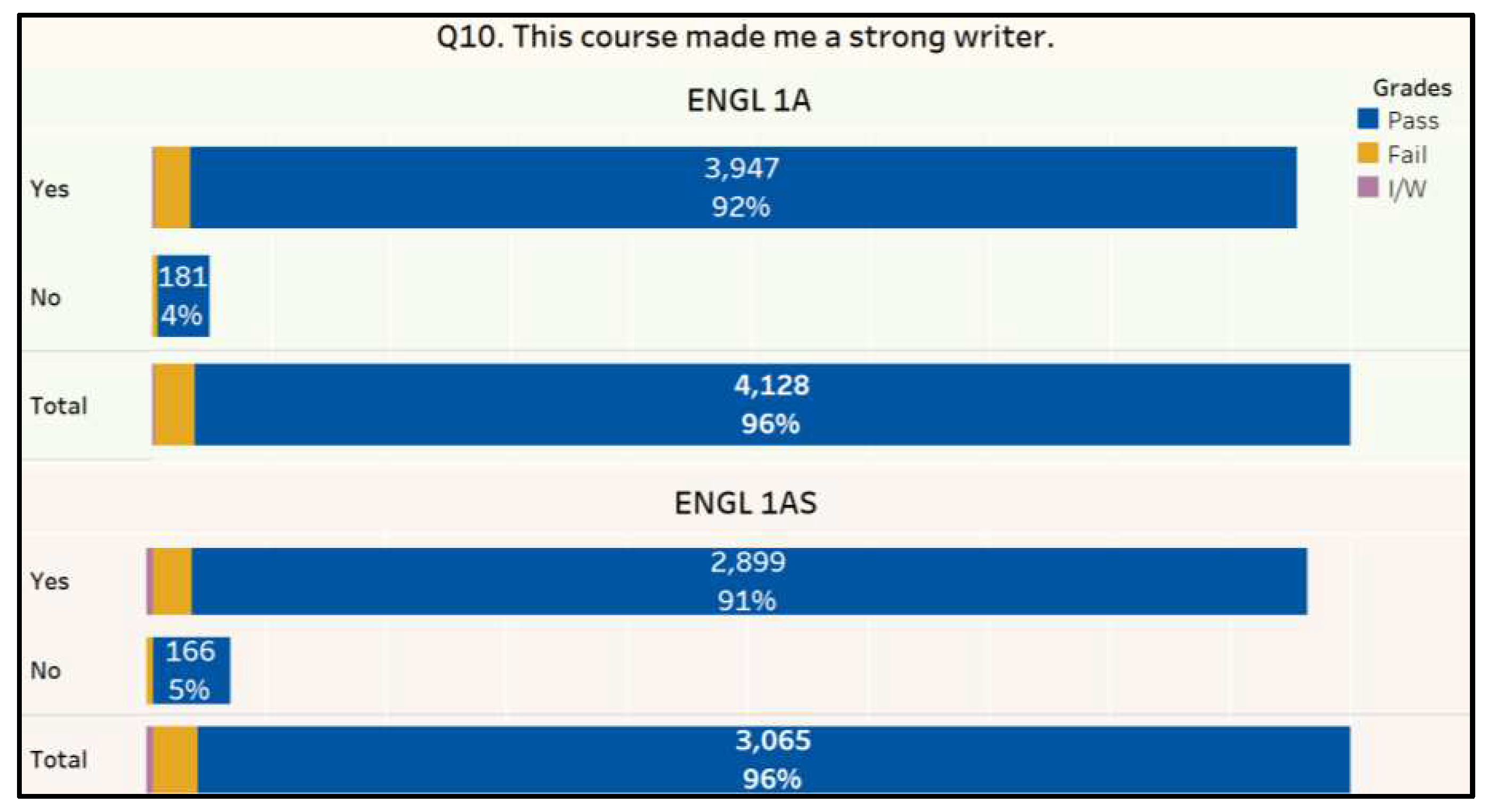

Figure 8.

More than 91% of students perceived themselves as good writers after completing their FYW courses. This number suggested positive student learning experiences either in one-semester ENGL 1A or two-semesters Stretch.

4.4. Factors affecting student learning

Outlier analysis was applied to analyze the predictors. The results showed that outliers existing among high school GPA, the level of writing comfort, writing confidence, reading comfort, and reading confidence. As those surveys were completed before students start their FYW program, it can show how students came to the program with various levels in psychological factors such as writing comfort, writing confidence, reading comfort, and reading confidence. As students entered SJSU with various high school GPA, outliers show the breadth of academic backgrounds that students had. As for other predictors, outliers were not detected. As the survey data of these predictors were collected after FYW program, it can also show students have similar learning experience after completing FYW program.

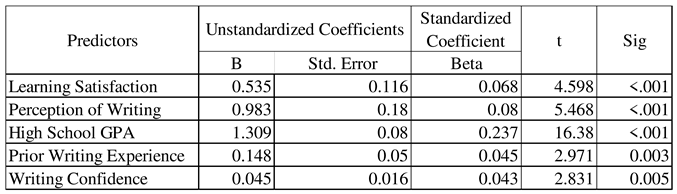

The outcome variable is academic grades in FYW program. Based on the results of regression models, writing comfort, reading confidence, and reading comfort are excluded in the final model. Among the predictors, reading comfort and confidence as well as writing comfort were not significant. Thus, these three predictors were excluded in the final model. The final model as shown in

Table 3 reveals that the predictors can explain 8% of the variance in academic grades in FYW programs according to the value of R².

5. Discission

The results showed that students had an enriched learning experience in the FYW program regardless of their backgrounds. The student body in the FYW program is diverse as revealed in demographics, prior learning experience, and psychological factors. Students came to the FYW program with those prior learning experiences and various levels of writing competency as suggested by outlier analysis. Their level of writing confidence, writing comfort, reading comfort, or reading confidence also varied; however, that did not impact much on their learning outcome. In other words, we did not find that higher levels of those abovementioned psychological factors affect students’ academic success. Previous studies also found that anxiety or students’ negative or positive emotions are related to their academic performance [

31,

32,

33]. It is also similar with how other studies found that how writing is being taught as part of the communication models [

34].

Students’ prior learning experience initially affect their course choice but that does not suggest course completion. It is a common belief that students’ high school GPAs reflect their prior academic preparation and another study also found that higher high school GPA decreases the likelihood of failing or withdrawing from class [

35]. In this study, students who had a higher high school GPA tended to enroll in the one-semester ENGL 1A rather than the two-semester Stretch. In contrast, students who had a lower high school GPA tended to enroll in the two-semester Stretch. The results showed that 73 one-semester writing course withdrew from the course regardless of their prior academic preparation and higher levels of writing/reading confidence and comfort. Although students who enrolled in the two-semester Stretch had lower levels of writing/reading confidence and comfort as well as academic preparation compared to their ENGL 1A, their academic performance is similar (94%). The result suggested that a lower high school GPA and lower levels of writing/reading comfort and confidence did not determine their final grade or course completion. Students’ persistence is the key factor whether students complete their chosen course. Undergraduates persist with their choice and understand the challenges they have to take in an accelerated one-semester class. The result is similar with other studies regarding student persistence in online courses in higher education [

36,

37].

Prior learning experience and psychological factors might affect the initial course choices of students; however, students’ persistence in choices predict their course completion in the FYW program. In the FYW program, undergraduates who chose the accelerated one-semester ENGL 1A need to persist by completing the challenges of more work and assignments. Undergraduates’ willingness to take on challenges is crucial for their learning [

38] and that also advances later success in life [

39]. When students persist with their choice and take on challenges during the course, their endeavor throughout the journey might help with later success.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected how colleges deliver education, universities have no choices but to adopt online learning as the primary mode of instruction. This shift has profound impacts upon student learning as well as their learning satisfaction. Students no longer had the choice to choose their preferred modality during that semester as online is the sole and only choice. Students who chose in-person or hybrid course had to switch into online mode during that semester. Another study found that undergraduates’ learning satisfaction is related to their performances in an online module [

40] as well as their success [

41]. The post-pandemic FYW study found that students had a higher level of learning satisfaction when they can choose their preferred modality [

42]. Other study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic also found that students’ preferences rather than their prior experience in technology affect their performance [

43]. Through choices again, students could create a learning experience best suited to their needs and preferred modality.

Another study found that students’ level of learning satisfaction is considered a crucial indicator for determining the quality of online education [

44]. Online education was first applied as a supplement to traditional in-person modality [

45]; however, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated such a trend. During the COVID-19 pandemic, at least 1.5 billion students worldwide have enrolled in some form of online education [

46] in asynchronous and synchronous mode [

47]. During that transition, both faculty and students might find insufficient time to teach and learn [

48,

49,

50,

51] and inevitably affect aspects more than learning satisfaction [

52,

53]. Yet another study found that a webinar is more effective in promoting knowledge compared to online and in-person modality; however, students had lower learning satisfaction in a webinar, online in contrast to an in-person modality [

54]. This could be a direction for future exploration of how faculty and students perceive teaching and learning in post-pandemic university.

The results of the regression model also affirmed that the academic journey that students undertook in class might be the key. Since students chose the class that best aligns with their needs, what students experience in courses including curriculum content or pedagogical techniques are essential. Other studies about college teaching [

55] or second language acquisition also suggested that pedagogy mattered [

56,

57,

58]. Pedagogical techniques, specifically what students experienced in class impact their learning. Some FYW instructors applied contract grading to their year-long courses. A study explores whether that created any impact upon student learning and found that FYW students who are in class with contract grading had higher academic achievement compared to their peers [

59]. Study have found that appropriate pedagogy not only improves students’ learning performance but also their engagement [

60]. This could be another area to explore the pedagogy contribute most to students learning in terms of their academic performance and engagement.

University admitted students from a diverse background and this current study found that what students chose and persisted in was their key to success. Student learning is a multi-faceted concept and the data collected in this study might not be fully captured everything. Infinite factors could affect students’ learning as well as their choices. For example, 1% of students who chose one-semester course had a higher withdrawal rate compared to their peers who chose and persisted. Although there are only 73 students, a qualitative study might be worthwhile to conduct in order to enhance student learning and inform future students. The reported data in this study represents what we were able to collect through RCW, Qualtrics, and paper survey. Although the response rate is decent, we did not collect all students who completed the FYW program. For example, the percentage of Asian and female students was slightly higher (within a 3% range) compared to the demographics of general student population. Another study examined physics found similar result that students’ academic performance can be attributed to learning occurred during the courses rather than students’ academic preparation [

61]. As the population of this study is freshmen, it might be worthwhile to explore whether other undergraduates are similar.

Acknowledgments

This paper would not be possible without peer support from the Writing Center, the English Department, and the College of Humanities and Arts at San José State University. This paper is inspired by the 10-year longitudinal study initiated by Dr. Cindy Baer and her dedication to the First-Year Writing Program and Reflection of College Writing.

References

- Bond, M., Buntins, K., Bedenlier, S., Zawacki-Richter, O., & Kerres, M. (2020). Mapping research in student engagement and educational technology in higher education: a systematic evidence map. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 17(2). [CrossRef]

- Chang, A., Kang, C., & Chang, D. (2023). Detecting female international students’ participation and satisfaction in higher education. ICIC Express Letter, Part B: Applications, 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Soerel, B., Plaatsman, L., Kegelaers, J., Stubbe, J., Van Rijn, R., & Oudejans, R. (2023). An analysis of teachers’ instructions and feedback at a contemporary dance university. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. [CrossRef]

- Drea, J. (2021). Improving learning outcomes through choice-based course delivery: The choice model. Journal of Education for Business, 1-8. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08832323.2021.1960469.

- Botti, S., & McGill, A. L. (2006). When choosing is not deciding: The effect of personal responsibility on satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(2), 211–219. [CrossRef]

- Feather, N. T., & Simon, J. G. (1971). Causal attributions for success and failure in relation to expectations of success based on selective or manipulative control. Journal of Personality, 39(4), 527–541. [CrossRef]

- San José State University. (2023, February 8). Supported Instruction. https://www.sjsu.edu/supportedinstruction/.

- Aprielieva, I. V., Demchenko, V. A., Kovalevska, A. V., Kovalevska, T. Y., & Hladun, T. S. (2021). Psychological factors influencing the motivation to study of students of TEI. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(SPE2). [CrossRef]

- Aneke, J. (2022). Influence of learning environment on the academic performance of secondary school students in Makurdi Metropolis. [CrossRef]

- Kienngam, N., Maneeton, N., Maneeton, B., Pojanapotha, P., Manomaivibul, J., Kawilapat, S., & Damrongpanit, S. (2022). Psychological factors influencing achievement of senior high school students. Healthcare, 10(7), 1163. [CrossRef]

- Veach, G. (2018). Introduction. In Teaching information literacy and writing studies: Volume 1, First-year composition courses (pp. xi-xvi). Purdue University Press Book Previews. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_previews/15.

- Lentschke, L. (2022, January 3-6). Dual credit first-year composition: Strategies in transitioning from high school writing to academic college writing. [Paper presentation]. The Twentieth Annual Hawaii International Conference on Education, Big Island, Hawaii, United States.

- San José State University. (2022, February 8). Frosh English. https://www.sjsu.edu/english/frosh/index.php.

- Heaser, A., & Thoune, D. (2020). Designing a corequisite first year writing course with student retention in mind. Composition Studies, 48(2), 105-115.

- Rasco, D., Day, S. L., & Denton, K. J. (2023). Student Retention: Fostering Peer Relationships Through a Brief Experimental Intervention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 25(1), 153-169. [CrossRef]

- Reiff, M. J., & Bawarshi, A. (2012). Tracing discursive resources: How students use prior genre knowledge to negotiate new writing contexts in first-year composition. Written Communication, 28(3), 312-337. [CrossRef]

- Teng, F., & Huang, J. (2022). Predictive effects of writing strategies for self-regulated learning on secondary school learners’ EFL writing proficiency. TESOL Quarterly. [CrossRef]

- Colomer, J., Serra, T., Gras, E., & Cañabate, D. (2021). Longitudinal self-directed competence development of university students through self-reflection. Reflective Practice, 22(5), 727-740. [CrossRef]

- Reflection of College Writing. (2023, January 30). Reflection of college writing, Retrieved and adapted from SJSU Canvas site.

- Scott, G. W., Furnell, J., Murphy, C. M., & Goulder, R. (2015). Teacher and student perceptions of the development of learner autonomy: A case study in the biological sciences. Studies in Higher Education, 40(6), 945–956. [CrossRef]

- Henri, D. C., Morrell, L. J., & Scott, G. W. (2018). Student perceptions of their autonomy at university. Higher Education, 75(3), 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Bault, N., & Rusconi, E. (2020). The Art of Influencing Consumer Choices: A Reflection on Recent Advances in Decision Neuroscience. Frontiers in Psychology, 21(10), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Beharu, W. (2018). Psychological factors affecting students’ academic performance among freshman psychology students in Dire Dawa University, Journal of Education and Practice, 9(4), 59-65.

- Ali, I., Khatak, M. I., Khan, W. U., Raza, S. H., & Munir, T. A. (2020). Adverse effect of tobacco smoke on renal disease in young healthy medical students: A cross-sectional comparative study. Professional Medical Journal, 27, 152–161. [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, S., & Varughese, J. T. (2017). Structured academic discussions through an online education-specific platform to improve Pharm.D. students learning outcomes. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 9(2), 230–236. [CrossRef]

- Lei, X. (2019). The investigation and suggestions on improving the psychological pressure of judicial personnel in criminal misjudged cases in China. Chinese Studies, 8(4), 184–193. [CrossRef]

- Chang, D. F., & Chou, W. C. (2021). Detecting the institutional mediation of push-pull factors on international students’ satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(20), 11405. [CrossRef]

- Fu, L., Li, J., & Chen, Y. (2022). Psychological factors of college students’ learning pressure under the online education mode during the epidemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 967578. [CrossRef]

- Alt, D., & Raichel, N. (2020). Reflective journaling and metacognitive awareness: Insights from a longitudinal study in higher education. Reflective Practice, 21 (2), 145-158. [CrossRef]

- Chang, A., & Smith, A. (2022, January 3-6). The empowering course choice: Identifying psychological perspectives and linguistic backgrounds that lead to college writing courses. [Paper presentation]. The Twentieth Annual Hawaii International Conference on Education, Big Island, Hawaii, United States.

- Pintrich, P. R., Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory, research and applications (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Senko, C., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2005). Regulation of Achievement Goals: The Role of Competence Feedback. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 320–336. [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. [CrossRef]

- Llorente, C., & Revuelta, G. (2023). Models of Teaching Science Communication. Sustainability, 15, 5172. [CrossRef]

- Al Hazaa, K., Abdel-Salam, G. A., Ismail, R., Johnson, C., Al-Tameemi, R., Romanowski, M. H., Ben Said, A., Ben Haj Rhouma, M., Elatawneh, A., de AraÚjo, G. (2021). The effects of attendance and high school GPA on student performance in first-year undergraduate courses. Cogent Education, 8 (1). [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M. S., Miller, R. M., McArthur, D., & Ogden, M. (2022). The Impact of Learning on Student Persistence in Higher Education. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 24(2), 316–336. [CrossRef]

- Lakhal, S., Khechine, H., & Mukamurera, J. (2021). Explaining persistence in online courses in higher education: a difference-in-differences analysis. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18, 19. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. (2012). Student Engagement and the Quality of Higher Education: A Contextual and Analytical Study of Current Taiwanese Undergraduates (Publication No. 3544661) [UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVIS]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/openview/3fee232bce29e883eb9754484613be43/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750.

- Fraser, W. J., & Killen, R. (2003). Factors influencing academic success or failure of first-year and senior university students: Do education students and lecturers perceive things differently? South African Journal of Education, 23(4), 254-260.

- Rajabalee, Y. B., & Santally, M. I. (2021). Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: Implications for institutional e-learning policy. Educational Information Technology, 26, 2623–2656. [CrossRef]

- Martin, F., Bolliger, D.U. (2022). Developing an online learner satisfaction framework in higher education through a systematic review of research. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(50). [CrossRef]

- Chang, A., Emanuel Smith, A., & Skinnell, R. (2022). Lessons learned from the pandemic: New modes of tech-supported instruction in first-year writing. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(5), 4700-4705.

- Looi, K. H., Wye, C.-K., & Abdul Bahri, E. N. (2022). Achieving Learning Outcomes of Emergency Remote Learning to Sustain Higher Education during Crises: An Empirical Study of Malaysian Undergraduates. Sustainability, 14, 1598. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T., & Xue, L. (2023). Satisfaction with online education among students, faculty, and parents before and after the COVID-19 outbreak: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1128034. [CrossRef]

- Kang, H., Zhang, J., & Kang, J. (2022). Analysis of online education reviews of universities using NLP techniques and statistical methods. Wireless Communication & Mobile Computing, 2022, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. (2022). Socioeconomic Inclusion During an Era of Online Education. Pennsylvania: IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Persada, S. F., Prasetyo, Y. T., Suryananda, X. V., Apriyansyah, B., Ong, A. K. S., Nadlifatin, R., et al. (2022). How the education industries react to synchronous and asynchronous learning in COVID-19: multigroup analysis insights for future online education. Sustainability, 14, 15288. [CrossRef]

- Tunc, S., & Toprak, M. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic and emergency remote education practices: effects on dentistry students. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 25(5), 621-629. [CrossRef]

- Ferri, F., Grifoni, P., & Guzzo, T. (2020). Online learning and emergency remote teaching: opportunities and challenges in emergency situations. Societies 10(4), 86. [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-C., & Chou, C. (2020). Online learning performance and satisfaction: do perceptions and readiness matter? Distance Education, 41, 48–69. [CrossRef]

- Rucsanda, M. D., Belibou, A., & Cazan, A.-M. (2021). Students’ attitudes toward online music education during the COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 753785. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X., Zhang, D., Lau, E. N. S., Xu, Z., Zhang, Z., Mo, P. K. H., et al. (2022). Primary school students’ online learning during coronavirus disease 2019: factors associated with satisfaction, perceived effectiveness, and preference. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 784826. [CrossRef]

- Parkes, K. A., Russell, J. A., Bauer, W. I., & Miksza, P. (2021). The well-being and instructional experiences of k-12 music educators: starting a new school year during a pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 701189. [CrossRef]

- Ebner, C., & Gegenfurtner, A. (2019). Learning and satisfaction in webinar, online, and face-to-face instruction: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Education, 4, 92. [CrossRef]

- Mellow, G. O., Woolis, D. D., Klages-Bombich, M., & Restler, S. (2023). Taking College Teaching Seriously-Pedagogy Matters!: Fostering Student Success Through Faculty-Centered Practice Improvement. Taylor & Francis.

- Alam, S., Faraj Albozeidi, H., Okleh Salameh Al-Hawamdeh, B., & Ahmad, F. (2022). Practice and Principle of Blended Learning in ESL/EFL Pedagogy: Strategies, Techniques and Challenges. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 17(11), pp. 225–241. [CrossRef]

- Al-Jarf, Reima. (2022, April 9). Role of Instructor Qualifications, Assessment and Pedagogical Practices in EFL Students” Grammar and Writing Proficiency. Journal of World English and Educational Practices (JWEEP), 4(2), 6-17. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4079841.

- Li, Z., & Li, J. (2022). Using the Flipped Classroom to Promote Learner Engagement for the Sustainable Development of Language Skills: A Mixed-Methods Study. Sustainability, 14, 5983. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A., Chang, A., & Smith, E. (2022). Pedagogical Approaches to Supporting Multilingualism in the First-Year Writing Classroom. 14th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, July 4-6, 2022.

- Chen, R. H. (2022). Effects of Deliberate Practice on Blended Learning Sustainability: A Community of Inquiry Perspective. Sustainability, 14, 1785. [CrossRef]

- Webb, D. J., & Paul, C. (2023). Attributing equity gaps to course structure in introductory physics. Physical Review Physics Education Research. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).