1. Introduction

In recent decades, growing territorial inequalities have promoted differentiated policies between different realities and, as a result, local welfare systems have become more and more significant [

21]. Within this framework, several areas of Italy suffer a double disadvantage, both geographical and social, also due to the phenomenon of depopulation of the most peripheral and vulnerable territories, especially in the South

1.

Therefore, in order to reduce these gaps, local welfare tends to foster, even more, measures to support Social Services and Services to the Person, as well as ad hoc actions aimed to increase job opportunities, especially to the youngest part of the population, because boys and girls, more than others, are escaping from their homelands and leaving their native countries.

In fact, according to AlmaLaurea 2023 Report, a good percentage (28.6% of young people) - just to attend university - migrate from Southern to Central and Northern Italy and this rate of the population rarely returns to own “home country” where social relationships established among people, in the form of social capital [16-68-23-58], may allow them to live better [

41], maintaining the bond between people and also boosting solidarity among them [

18]. The social bond - more than any other element - could become a possible protection factor, to enable citizens to remain in a specific place, to react to the risk of vulnerability and to contrast possible critical events [38-50-66] both of a personal and socio-environmental nature.

However, in complex societies, it’s difficult to find the characteristic of the community resilience

, understood as a social [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74] cultural [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29], economic [

65], political [

60], and territorial system [

40], causing young people to go away from their territories.

In this framework, the essay, taking into account the phenomenon of depopulation in relation to the Index of Social and Material Vulnerability (IVSM), aims to find strategies [

52] to provide a territorial re-centralisation [

11], especially for those communities located in the Areas called as “Inner” (named as in France “forgotten territories” by the State and by the Market or, again, as in England, “territories left behind” or, even, as in Spain the “empty Spain”) [

67].

The essay, through the findings of an exploratory study conducted in the Molise region, critically analyses behaviours of young people between risk factors and possible social interventions for social change [14-3]. On these depends the desire to stay or to leave their own “Community”

2 [

13], which is often determined by being born and by being raised in the “right” place (or not “right”) of the Italian peninsula.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Vulnerability as a multidimensional concept

Social

3 and material vulnerability, as a multidimensional concept

4, aims to analyse how «the autonomy and self-determination capacity of individuals are permanently threatened by not being always involved in the main social integration and resource distribution systems» [

69] [

45] (p. 8)

5. In this frame, in order to implement successful of prevision and prevention measures to mitigate the risk of social vulnerability, it is important to consider the spatiotemporal analysis [

35].

In particular, the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) defines vulnerability as «the characteristics and circumstances of a community, system or asset that make it susceptible to the damaging effects of a hazard» [

82] (p. 30).

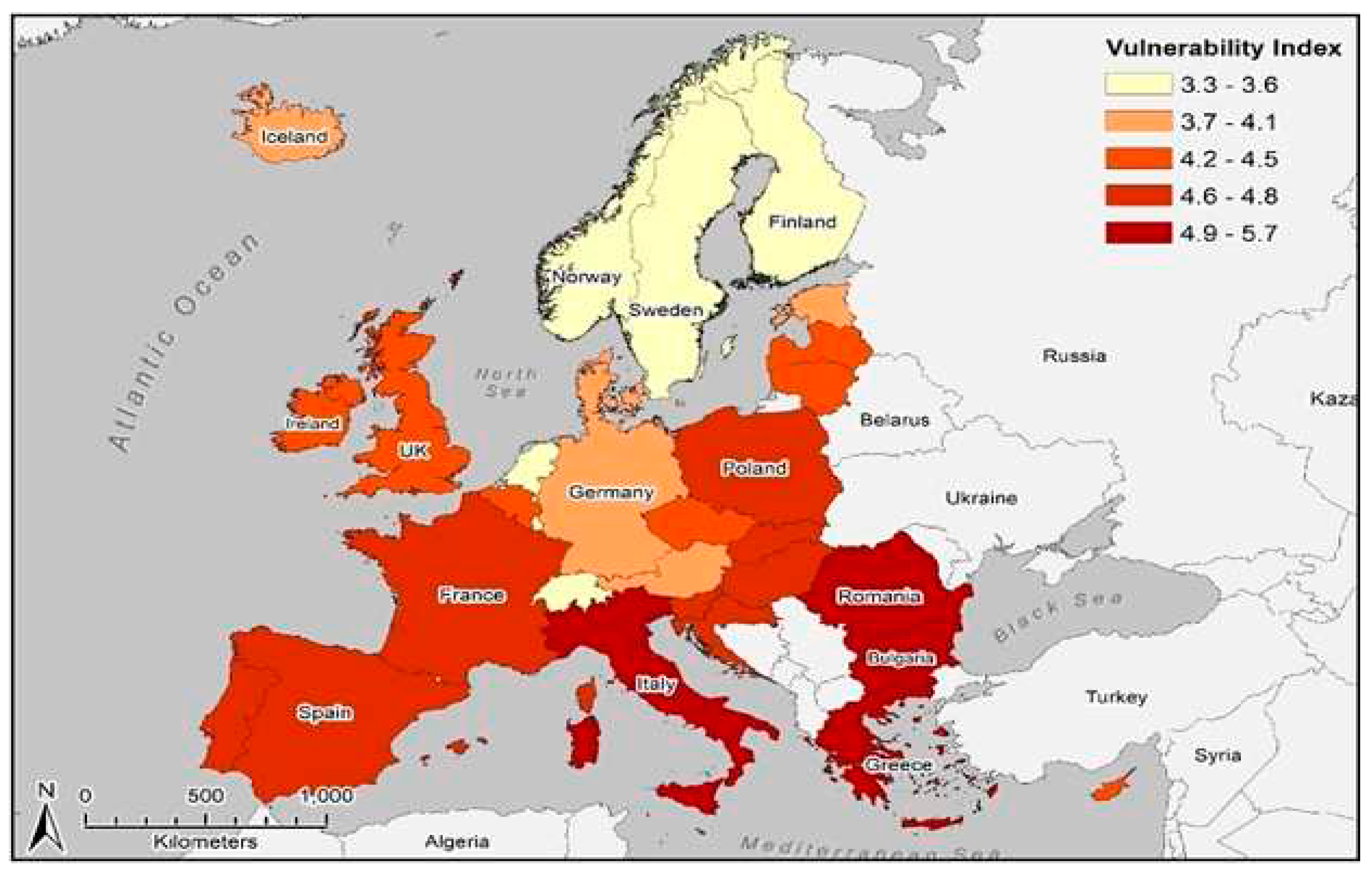

Moreover, the concept of

country vulnerability, that in Italy - according to the European Commission - reaches among the highest values in Europe (

Figure 1), understood as «the risk of being affected by exogenous shocks, from various origins (external, natural, in particular climatic, or socio-political)» [

81] (p. 14).

This definition is particularly important because it refers to an unknown future living conditions and these are potential source of social risks and needs for “different social groups, which have different abilities to react and to manage the effect of natural hazard-related processes” [61-83-27-85-1-12].

For example, younger generations, particularly inhabitants of Inner Areas of Italy (regions that are more at risk than developed ones), live a great inequality that exposed them to risk of social vulnerability. So, on the one hand, the desire to leave their community is growing among younger, on the other hand, the desire to deal with extreme adverse conditions is falling down.

For this reason, social vulnerability through spatiotemporal analysis, like a process to identify and define the potential, aspirations and needs for sustainable human development of a given territory, could contribute to identify long-term policies, in coherence not only with National, European and extra-European strategies (National Strategy for Inner Areas; National Plan for Recovery and Resilience; Next generation EU, Agenda 2030), but also with bottom-up social policy.

This bottom-up approach considers the person not as a passive final subject of social benefits, but as an active, emancipated subject that participates to the co-creation of well-being

6 [

41].

2.2. Welfare and Inner Aareas

Over the years, this

rationale is also grounded thanks to the central role that civil society assumes in making welfare, because there was an important change from a traditional

welfare state to a

welfare society [

33]

7. In other words, it is the so-called

community welfare [

26], also defined as

proximity welfare [

56]. This Welfare, try to satisfy to citizens needs through dedicated services (like social services) in order to monitor territories. And this analysis is reporting a worrying socio-demographic crisis above all for the Inner Areas of Italy where the “demographic decline” in the last 15 years, reaching a denatality rate of over 30% [

47].

Among factors that cause this low birth rate, there is the uncertainty about the future that is a burden especially for young people searching for a job. In fact, this social category struggles to enter to the labour market, pushing further and further away the possibility to have independence, the time to have their own family and to have children [

44].

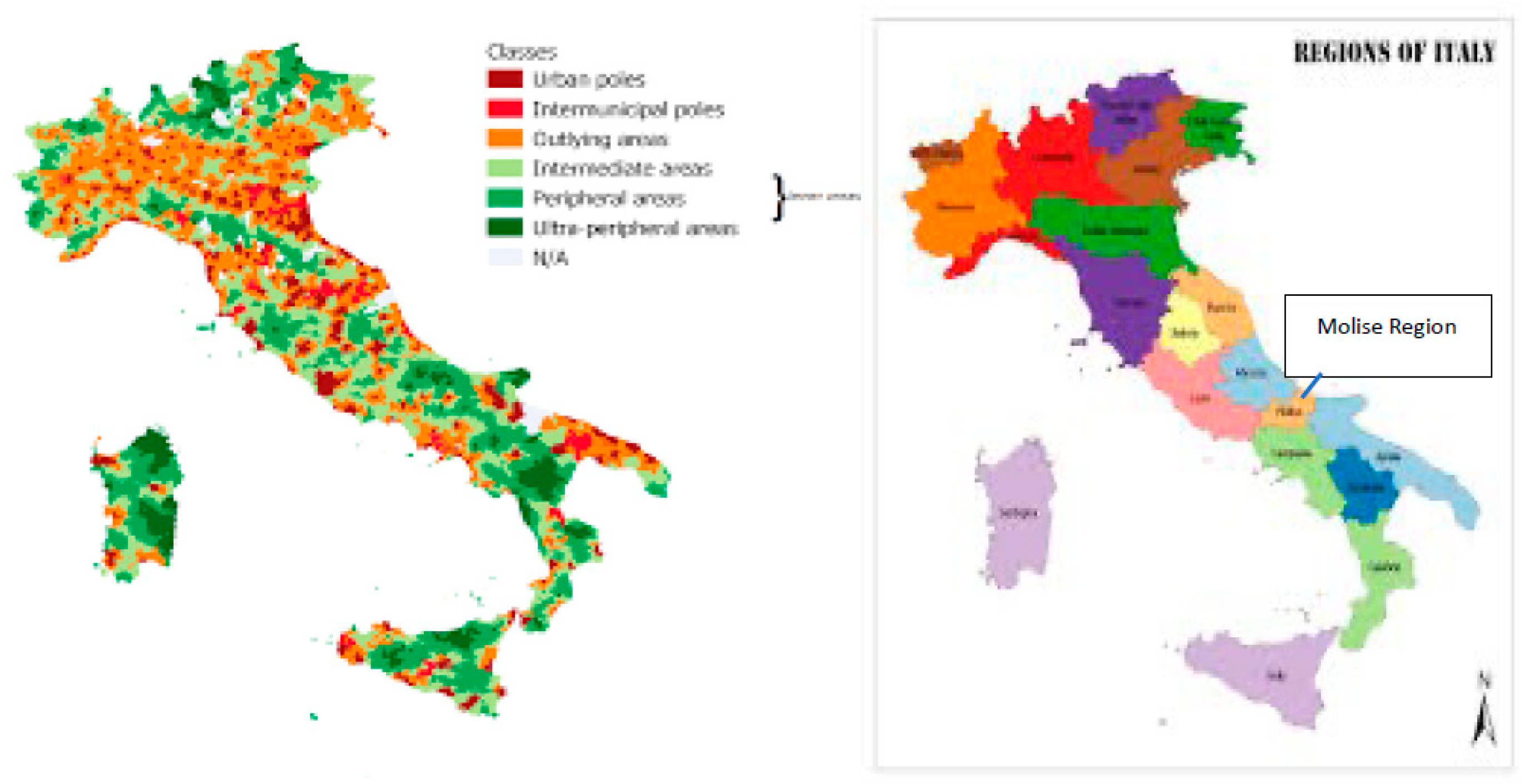

More than other territories, Inner Areas - which don’t provide infrastructures (adequate education, mobility, care, assistance, and services for early childhood such as kindergartens) – “are aging” and they will continue to suffer the permanent tendency of the younger population to leave the rural communities [

57], causing a further increase in vulnerability

8.

Especially in the Molise region

9, as Inner Area and as a rural and peripheral territory, suffering from depopulation, in which the exploratory research was conducted.

On this topic, discussed by «the Council and by the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, become crucial to increase opportunities for young people in rural and remote areas also involving EU Member States, in order to promote and to facilitate the active citizenship and the meaningful participation of younger from diverse backgrounds» [

24].

Participation in these processes should take place through appropriate instruments, such as the promotion of cooperation between administrations at all levels (horizontal and vertical principles subsidiary), where «including grassroots youth activities» [

31].

2.3. Some social causes of depopulation

In the interdisciplinary approach concerning the topic of social vulnerability, the dimension of depopulation, as demographic migration, is a multidimensional social event that can be analysed at the macro level, through the institutional and political system (from the perspective of global and local welfare), and through the micro level, by observing individuals behaviours and their motivations (voluntary or imposed), subtended the decision to stay or leave a territory [

36,

37].

Causes that most frequently emerge, are represented by the Inner Areas inhabitants’ “not adequate” socio-economic conditions (related to employment opportunity issues) [

8]. In addition, as authors stressed in the paper, it is important to take into account others problems: the connection infrastructure insufficiency and the difficulty to create networks between social, educational, cultural and school services, the climate change, the migration “emergency” and the crisis of the traditional welfare system [

19].

In particular, Inner Areas are losing territorial capital, missing historical-cultural heritage, both material (monuments landscapes, etc.) and intangible (languages and dialects, traditional knowledge, etc.) [

5], as well as, the social and human capital.

In fact, these “questions” are really significant for Inner Areas - which have to cope with demographic dynamics such as the aging population and the low population birth rate – all these crisis connected to the “new poverties”, that is a multifaceted and complex phenomenon that all welfare states seek to mitigate in various way, are now emerging with greater speed.

In any case, historically, the rural areas are been marked by constant processes of marginalization

10 that have produced isolation and impoverishment of their territories. These elements have negatively impacts on the community, which becomes poorer and poorer, affecting the identity of its citizens.

Thus, the complex condition described, requires a consideration of both the strengths and the weakness of the territorial area, also in terms of vulnerability risk, in order to evaluate public interventions [

28], as well as in a joint effort of all institutional actors and Intermediate Bodies [

2], because it is crucial to implement strategic actions useful to achieve a more sustainable and attractive development of “edge” territories [

11].

«This means that the systems of dissemination reporting, in agreement with the Charter of Shared Social Responsibility (2011) and the more recent Strasbourg Declaration (2014), may also be a model of social economic development» [

41] (p. 50) more equitable, greener and “anchored” in local communities.

A development model where values of social cohesion

11 are a authentic source for the collective well-being

12. In this way, the community could have a healing effect to prevent many critical situations [

77] in smaller territories: in fact, all the communities are “competent” [

51] in re-design the already existent institutional patterns of intervention into resources of possible activation. The risk management (in its several manifestations: natural disasters, violence and crime, socio-cultural variables and political, economic and geographical factors) is strategic for the activation of responses that must be preventive and positive [

56].

In this framework, the social capital [16-68-23], the intergeneration ties

13, the solidarity [

43], the sense of community [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72], the value of belonging to a community [

53], and involvement [

87],... are all factors that make the difference in the dynamics and processes of depopulation of Inner Areas [

79], as well as those gathered from the Molise exploratory research.

For these reasons, institutions might be reflect on themself in terms of protective factors and on risk factors in the local community, as well as, to find a balance of the economic and social elements.

It is important to envisage a theoretical framework designed to assess and to measure the multidimensional well-being of individuals and communities and to this end it is crucial to create a new collaboration for individual and collective well-being oriented towards an integrated approach; to change the actual economic paradigm, recognising the limitations of economic indicators as the unique measurement for development; To take into account environmental degradation and ecological limits [

75].

Indeed, the many and complex environmental and institutional challenges require a new direction, aimed to promote policies for sustainable development and its Goals – (17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations, 2015), aimed to encourage partnerships between public, public-private and civil society actors.

All Actors acts in a cohesive manner on how the territory can become the place for the realization of the need of present and future generations, increasing the social and economic opportunities of the women, men and young people who inhabit the territory.

2.4. Study Area

The study, an exploratory social research, was conducted in Molise region (March 2023), and it focused on the topic of relationship between Molise region younger generations and phenomenon of depopulation. This migration typical of vulnerable Inner Areas is particularly relevant in “our” study area where young people, for different reasons, choose to leave their birth-place.

Specifically, the total resident population of Molise amounted to 289,840 (1

st January 2023), a decrease of almost 8% in the last 12 months [

48]

14.

Moreover, between 1951 and 2019, a little village named “Provvidenti” in Molise region, experienced a strong percentage contraction of the resident population, amounting to - 83%.

Other villages in this area are experiencing a similar decline

15. In addition, the demographic forecasts for the near future are certainly not positive

16. In particular, are the “Borgo’s” (hamlets) in Inner Areas of Molise those who suffer from these losses.

This trend simulates what happens at a more general level. In fact, the youth population has constantly decreased in Europe over the past decade.

According to the data provided by Eurostat, the number of young people has decreased for EU-28 (2013-2019) for the age group 25-29 from 6,949.2 to 5,881.3 millions [

32].

2.5. The research problem and data collection

Within this framework, the aim of the research is to investigate the future needs and expectations of adolescents and young adults (15-34 years old) in the Molise area in order to understand what kind of interaction they have with the territory in which they live, the reasons they give for the phenomenon of depopulation and the motivations that usually push young people to leave and, sometimes, to return to Molise.

As a result, the aim of this essay, is also to identify useful indications for planning social welfare policies to contrast the phenomenon of depopulation in the Molise area and to contain the condition of uncertainty - and of social vulnerability - in which the young Molisians generations live.

First of all, based on these questions, was conducted a literature review regarding the main topic in a sociological integrated perspective with a quantitative approach thank to data was collected through a semi-structured online questionnaire

17, filled out by 89 young respondents, aged between 16 and 32 (in March 2023).

Authors choose the exploratory approach of research because the causes of youth depopulation from Inner Areas are multiple, often difficult to identify.

Therefore, the research problem is articulated in the following cognitive questions:

1) Why do young people leave Molise region?

2) Which strategies and actions should be adopted to offer the re-centralisation of territories and to limit social vulnerability in the future?

3. Results

Empirical evidence shows that respondents are mostly young female students (78.7% versus 21.3% male): the sample is composed by 71.8% of 16-19-year-olds, 19.8% of 20-24-year-olds, 5.2% of 25-29-year-olds and 3.2% of 30-32-year-olds. Among these, 96.6% live in Molise - mostly in the Inner Areas - with their family and they are students (95.5%).

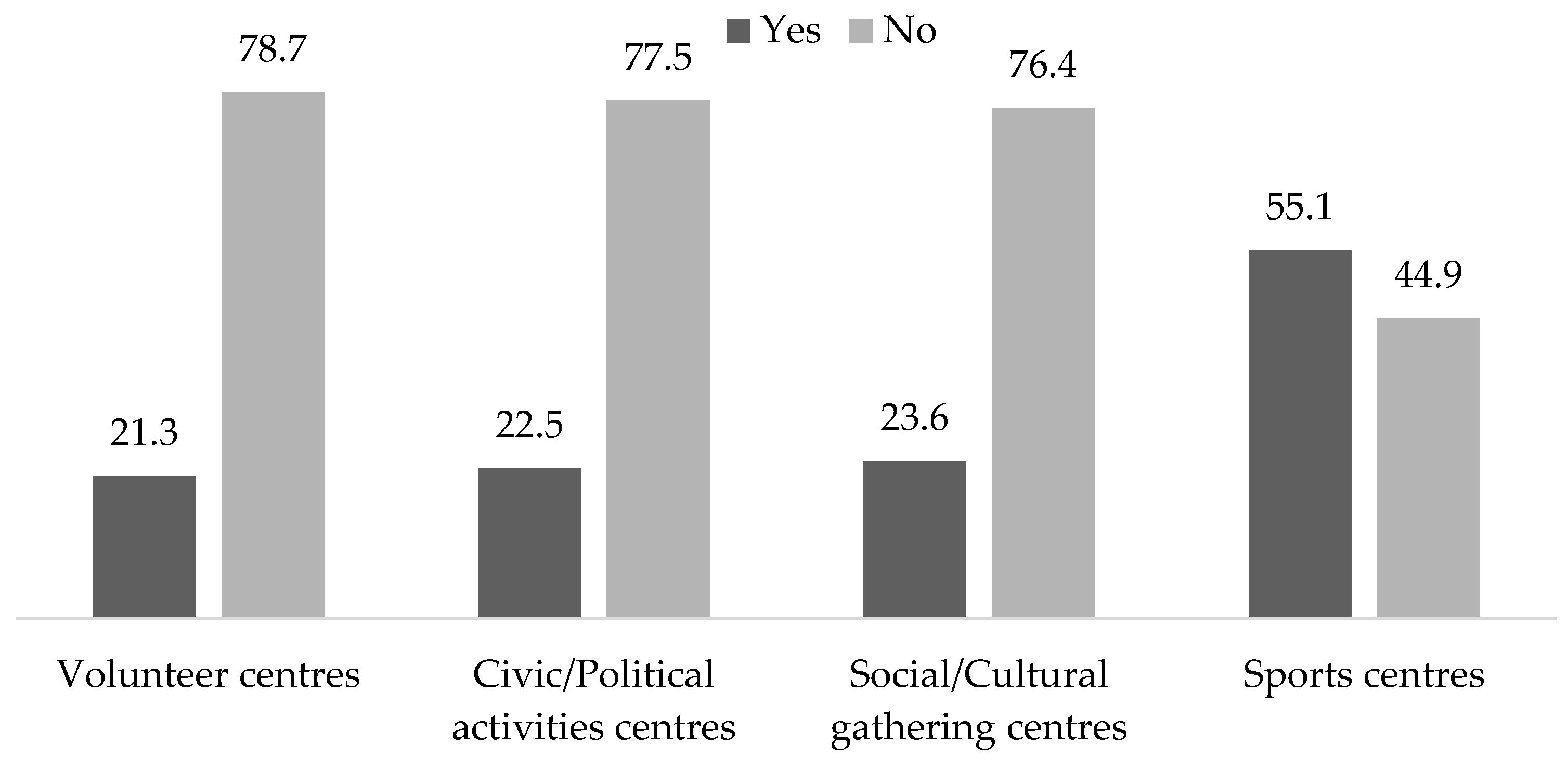

Many of young people interviewed reported that they are not fully active within the territorial communities in which they live (

Figure 3): in fact, a very few of them are involved in volunteer centres (21.3%). Similarly, just 22.5% participate in civic and political activities and just 23.6% attend socio-cultural centres, while more than half of the sample (55.1%) says that they frequent local sports centres.

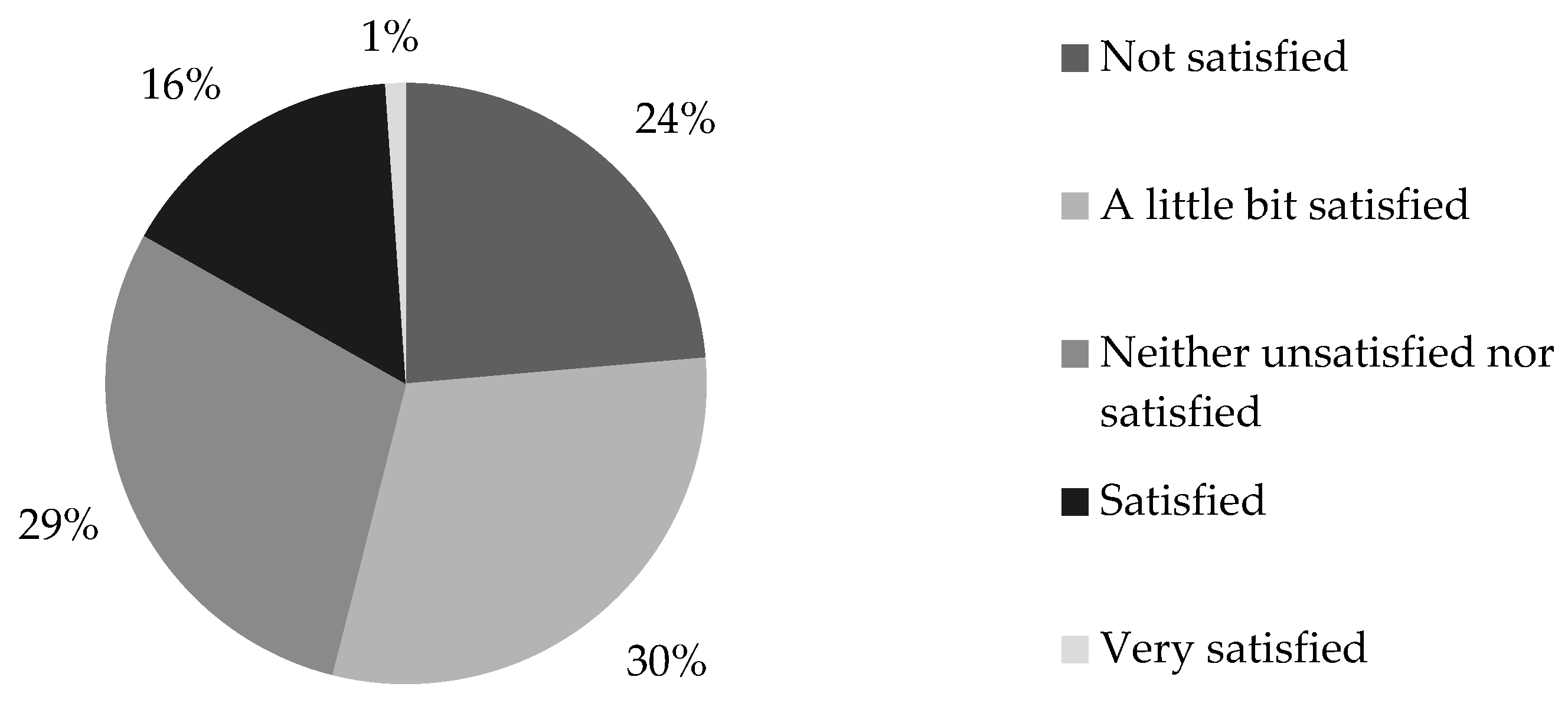

Regarding life satisfaction within communities, almost half of the sample (54,9%) says that they are not satisfied, while just 16.8% of are satisfied and the rest of them is neutrally about their life. In any case, their family life and their friendship ties are very positive as fundamental of their familist welfare (80%)

18 (

Figure 4).

In particular, 33.7% of the respondents argue that the territory where their live does not promote the community well-being, reporting a lack of major health services, sport facilities, cultural and social associations (61.8% respectively), and also schools (60.7%), transports infrastructures (55.1%), banks and post offices (32.6%), universities (28.1%) and training centres (25.8%).

Moreover, more than half of young respondents (53.9%) declares to daily travel to reach school or university (76.4%), to go shopping (74.2%), to receive medical treatment and specialized examinations (58.4%), to go to the cinema, theatre or museum (47.2%), and even to meet friends (51.7%).

An interesting finding - which is connected to the theme of Should Young stay or should Young go - is linked to the social-cultural patterns: most of all (98.9%) believe that they live in a small town mentality. Indeed, «there are only old people», «people are not open to each other», «there are prejudices», and there is a «constantly judged».

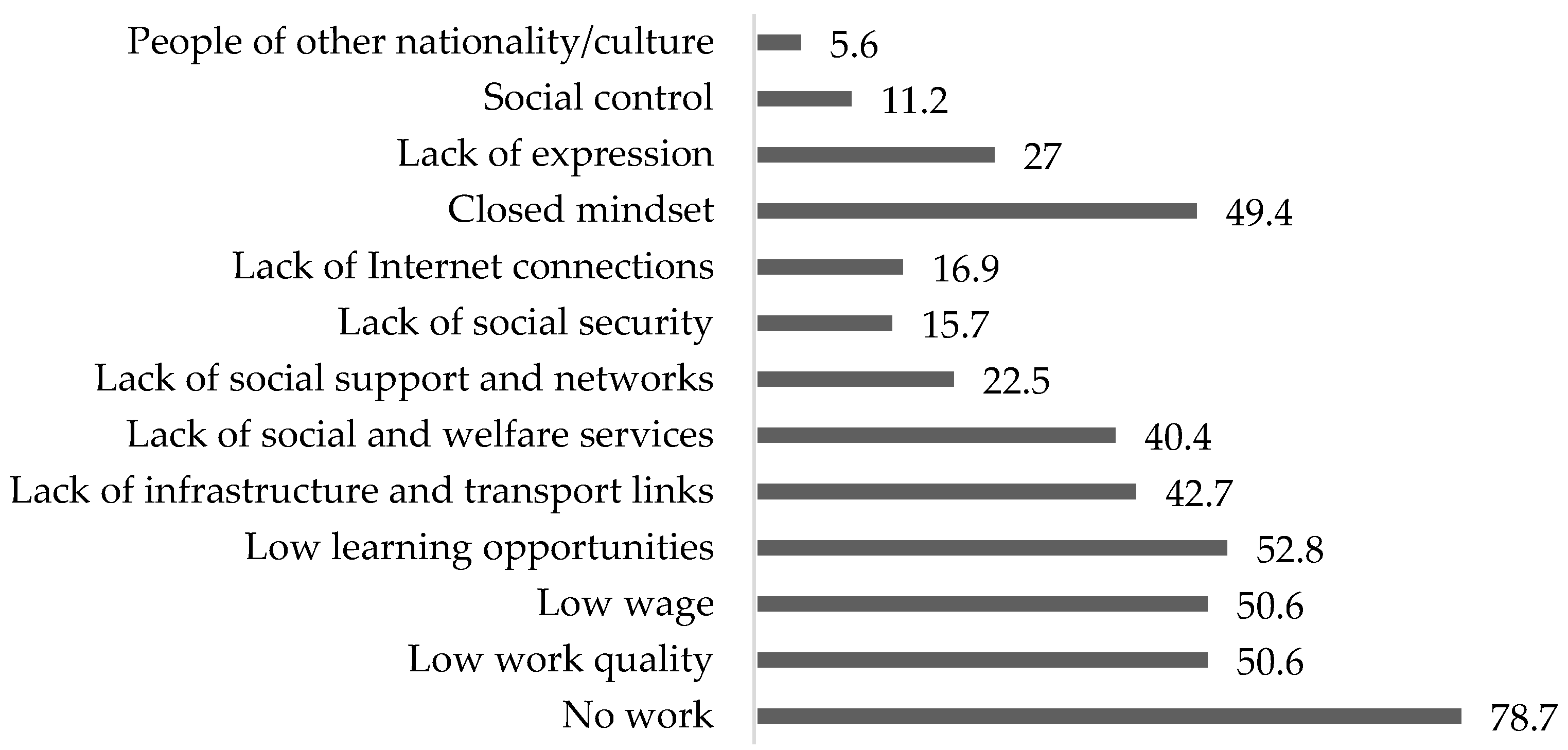

People mentality change is not more easily (49.4%), the “absence” of jobs (78.7%), low educational opportunities (52.8%), the humble salary (50.6%) and the lack of infrastructure and connections (42.7%) as well as the inefficiency of social and welfare services (40.4%), representing the main reasons that contribute to Molise region depopulation (

Figure 5).

In addition, more than 43.8% of the sample say they would go away from Molise because «there are very few opportunities for personal and economic growth» and, therefore, «there is no life choices» because institutions and politics fail to respond to the needs of those young people who decide to stay in this geographic area (53.9%). According to the respondents, the main depopulation responsible actors are the government (61.8%), local authorities (62.9%) and the consequently inadequate welfare policies (47.2%).

The young people interviewed say to leave Molise (41.6%) because they want to «find more opportunities», to «have better life chances» and to create a «better life expectancy».

However, respondents indicate some possible solutions that might fight the phenomenon of depopulation such as natural and cultural resources (68.5%), specific productive activities (52.8%), proximity services for population (48.3%), the creation of new services (41.6%), and of opportunities to support young people to let them “stay and don’t go”.

Politics should encourage the access of young people in workplace

19 (89.9%), creating much more educational opportunities coherent to the excellence present in the territorial area (73.0%), arranging connections and infrastructures (49.4%), creating and modifying work orientation from school (44.9%) and reinforcing social welfare services (43.8%).

In fact, schools and universities play a crucial role in order to create work-oriented possibilities in the territory (68.5%), to ideate more efficient school-to-work alternation agreement (61.8%), to strengthen the internship activities in degree programs (51.7%), to network cooperate with others universities and nearby areas (42.7%).

There are also other motivation explaining the choice to leave Molise by younger but it is important to stress the National Strategy of Inner Areas and the new National Recovery and Resilience Plan that can represent a real challenge to foster better life chances for all young generations living in the Inner Areas of Italy.

4. Discussion

Nowadays, challenges for Inner Areas and the younger generations living there, are many and reflect multiple factors, as demonstrated by the exploratory research discussed here.

It is important to consider active participation in the “Community” through political, socio-cultural and voluntary actions

20. Indeed, «the social value and function of voluntary activity is an expression of participation, solidarity and pluralism, promotes its development while safeguarding its autonomy and encourages its original contribution to the achievement of social, civil and cultural goals»

21.

The possibility to be actors in processes of change relates to the possibility of knowing the territory and affecting it at the political level, in order to be able to imagine positive strategies for citizens from an horizontal welfare level. Sharing and cultivating common values in proximity, thanks to the collective consciousness as «the set of beliefs and feelings common [...] to the members of the same society» [

30] (p. 46), means to make that community more competent and “resilient” in different aspects [

17]. It means create a better bond for social cohesion, for solidarity and to reduce social, cultural, and economic inequalities [

34]

22. Unfortunately, from what has emerged, solidarity is in danger with also the only imagined possibility, to change the community in the future perspective.

In this regard, emerges a high dissatisfaction rate (53.9%) which can be considered a measure of belonging and of quality of life. National and local policies, with the welfare system, should work toward this direction: put at the centre of discussion the satisfaction of the younger generation as an indicator, among others, of holistic well-being. Not surprisingly, employment status may contributes to well-being along with “good” health status and economic support.

It must be considered the productive economic vocation of the Molise region that is dedicated to agricultural, manufacturing and artisanal activities, covering important enterprises [

9] (p. 18)

23. In fact, depopulation and socio-demographic dynamics, impact on the communities economy, their livelihoods and their future development. If policy does not and will not invest in measures in order to promote the rate of births, labour market participation, and the (re)organization and management of migration flows, «the region’s economic-social growth will suffer a strong and further decline» [

9] (p. 22).

On the other hand, the inadequacy of infrastructure connections makes community empowerment very difficult; just look at the data related to the daily commute of young people interviewed, for basic and necessary needs. In this sense, the scarce presence of social welfare services and social support should be emphasized: already in 2014, the “regionalized” health care system, recorded a certain imbalance of care provision in favour of hospital care no longer able, however, to respond effectively and appropriately to the changed epidemiological and demographic framework for which an integrated model is needed

24.

There is, as seen, an imbalance for educational and training services that are experienced by the sample, felt as insufficient and inadequate to the needs of the population. In this regard, the educational poverty issue specifically to Molise should be highlighted [

42]: kindergartens and early childhood services in this region offer 1,224 places compared to about 6,000 children under the age of 3; the supply these services in Molise is 44.1% compared to a national average of 59.3% [

62]

25.

It is fundamental for the younger to receive appropriate skills and to attend quality college as two main emancipation “social” tools.

Consequently, attention should be paid on protective resilience factors (social, cultural, economic and political) that make possible to respond adequately to the needs of the local population, thinking in terms of preventing social vulnerability, promoting culture and strengthening social welfare services.

The National Strategy for Inner Areas (SNAI)

26, for example, including (among others) these areas of intervention (essential services and local development) and, at the regional level, is in line with other policy instruments, such as the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)

27 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

As Johan Rockström reminds us, the global economic system must be fundamentally rethought by (re)connecting it to the biosphere and the resources that the Earth makes available

28 [

71]. A new form of integrated, proactive, and collaborative governance that must work on equity and on inclusion: it this way it is possible to respond to the ever-increasing risks and different vulnerabilities.

The political and administration level have to think about a real proximity welfare, to enforce actions that improve and emancipate their communities through the implementation of the interventions provided in the Plans. At the same time, it is therefore essential to structurally invest in economic policies, particularly in labour and family policies, in health and welfare policies and in the geography of the regional territory. Otherwise, the risk more than real, is that of backsliding to the point of shutting down the community even in its extreme consequences connected to resilience and the future sustainability.

5. Conclusions

Considering the many suggestions that emerged from the exploratory research conducted in the Molise region, it is clear how crucial local participatory networks for the renewal of local welfare systems are, along with the active involvement of the people-citizens of that area. In particular for Inner Areas that should (re)consider people’s needs in light of the demographic, climatic, socio-economic and political crisis that grips them.

According to Governa and Salone (2004), the territory, in fact, should no longer be understood as a static and passive space: «territories [...] show themselves rather as dynamic, active territorial spheres, whose form and limits are defined in the shared action of the subjects that operate in them» [

39] (p. 797). The concept of territory is in coherence realized «only if and when the mobilization of territorial groups, interests and institutions enables the local system to behave and act as a collective actor» [

39]. This process does not happen spontaneously: an action can be properly defined as “territorial” only if it is shared among the territorial actors themselves and, in particular, if it aims to enhance and «increase the value of territorial resources, understood in the most varied and broadest possible way» [

39] (p. 815).

Thus in the reading of the territory it is clear the community as a broader sociological category that is inclusive of complex social action: it is social identity and belonging to a group that (can) generate(re) solidarity: it is «a set of subjects who share significant aspects of their existence and who, for this reason, are in a relationship of interdependence, can develop a sense of belonging and can entertain trusting relationships with each other» [

54] (p. 13). Feeling like a “community” [

20] implies being active citizens, with rights and duties; the latter must be placed at the centre of policy and welfare where fragmented interventions can no longer be imagined. Indeed, the dimension to be considered is glocal - neither just local, nor just global.

In this framework, it is clearly visible how proximity welfare, appropriately assisted by the resources belonging to the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, can act as a flywheel to counter the depopulation Inner Areas of Italy enacted by the younger generations. They are the ones who often propose, as evident from the data of the exploratory research presented, proactive actions that, being varied and multi-level, could offer a re-centralization of the territories, reconciling it with the universalism of rights.

In conclusion, it is a matter of putting ideas such as vulnerability and sustainability at the centre, and thus focusing on a «conception for which current decisions should not harm the prospects of maintaining or increasing living standards for the future» [

6] (p. 2033), particularly for those living in Inner Areas of Italy. This is possible by preserving natural resources, ensuring the growth and development of the areas, and improving the living conditions of the younger generations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: Vulnerability index at country level; Figure S2: Map of Inner Areas of Italy; Figure S3: Frequency of territory centres (%); Figure S4: Degree of life satisfaction in the territory (%); Figure S5: Reasons for depopulation in the territory (%); Table S1: Resident population of Molise Region, years 2022-2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.; methodology, D.G. and D.B.; validation, D.G., M.D. and D.B.; formal analysis, D.B.; investigation, D.G. and M.D.; data curation, D.G., M.D and D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G. and M.D. writing—review and editing, D.G., M.D and D.B; visualization, M.D.; supervision, D.G. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented are not publicly accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement:

The research was conducted with full respect for the participants and research partners. The data was anonymized so that it could not be linked to the respondents of the

survey.

References

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 2006, 16, (3), pp. 268-281. [CrossRef]

- Agenzia per la coesione territoriale. Intermediate Bodies. Roma, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/lacoesione/le-politiche-di-coesione-in-italia-2014-2020/the-actors/intermediate-bodies/?lang=en.

- 3. AHPRU. A Study of Resiliency in Communities. Ottawa: Health Canada, 2000.

- Almalaurea. Mobilità per studio e lavoro. Almalaurea, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.almalaurea.it/sites/default/files/2023-06/4_Approfondimento_mobilit%C3%A0_per%20studio%20e%20lavoro_0.pdf.

- Amodio, T. Una lettura della marginalità attraverso lo spopolamento e l’abbandono nei piccoli comuni. Bollettino della Associazione Italiana di Cartografia 2021, 172, pp. 50-65. DOI: 10.13137/2282-572X/33544. [CrossRef]

- Anand, R. S.; Sen, A. Human Development and Economic Sustainability. World Development 2000, 28, (12), pp. 2029-2049. [CrossRef]

- Angeon, V.; Bates, S. Reviewing Composite Vulnerability and Resilience Indexes: A Sustainable Approach and Application. World Development 2015, 72, pp.140-162. [CrossRef]

- Avallone, G. La sociologia urbana e rurale. Origini e sviluppi in Italia. Liguori Editore: Napoli, 2010.

- Banca d’Italia. Economie Regionali - L’economia del Molise. Banca d’Italia: Roma, 2023.

- Banfield, E. C. The Moral Basis of a Backward Society. Free Press, 1958.

- Barca, F.; Casavola, P.; Lucatelli, S. Strategia nazionale per le Aree interne: Definizione, obiettivi, strumenti e governance. Collana Materiali UVAL: Roma, 2014.

- Barros, V. R.; Field, C. B.; Dokke, D. J.; Mastrandrea, M. D.; Mach, K. J.; Bilir, T. E.; Girma, B. Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: Regional aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2014.

- Bauman, Z. Missing Community. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 2008.

- Blaikie, P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I.; Wisner, B. At Risk. Natural Hazards, People’s Vulnerability and Disasters. Routledge: London, 1994.

- Bodin, Ö.; Guerrero, A.; Nohrstedt, D.; Baird, J.; Summers, R.; Plummer, R.; Jasny, L. Choose your collaborators wisely. Public Administration Review 2022, 82, (6), pp. 1154-1167. [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. Le sens pratique. Minuit: Paris, 1980.

- Bravo, M.; Rubio-Stipec, M.; Canino, G. J.; Woodbury, M. A.; Ribera, J. C. The psychological sequelae of disaster stress prospectively and retrospectively evaluated. American Journal of Community Psychology 1990, 18, (5), pp. 661-680. [CrossRef]

- Breton, M. Neighborhood resiliency. Journal of Community Practice 2001, 19, (1), pp. 21-36. [CrossRef]

- Carrosio, G. I margini al centro. L’Italia delle aree interne tra fragilità e innovazione. Roma: Donzelli, 2019.

- Chavis, D. M.; Wandersman, A. Sense of community in the urban environment: A catalyst for participation and community development. A quarter century of community psychology 2002 Springer: Boston, pp. 265-292.

- Cibinel, E.; Maino, F. Valoriamo: reti partecipate per un welfare aziendale a misura di territorio. In Il ritorno dello Stato sociale? Mercato, Terzo Settore e comunità oltre la pandemia. Quinto Rapporto sul secondo welfare in Italia 2021 Maino, F. (eds) Giappichelli: Torino, 2021.

- Clauss-Ehlers, C. S.; Lopez Levy, L. Violence and community, terms in conflict: An ecological approach to resilience. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless 2022, 11, (4), pp. 265-278.

- Coleman, J. Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1990.

- Council of the European Union. Raising Opportunities for Young People in Rural and Remote areas, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/44119/st08265-en20.pdf.

- Corbetta, P. Metodologia e tecniche della ricerca sociale. Il Mulino: Bologna, 1999.

- Cugno, A. Il potere istituente del welfare comunitario: considerazioni a margine. In Welfare responsabile Cesareo, V. (eds). Vita e Pensiero: Milano, 2017.

- Cutter, S. L.; Boruff, B. J.; Shirley W. L. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social Science Quarterly 2003 84, (2), pp. 242-261. [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, L. Welfare di comunità e inclusione sociale. Rivista del Diritto della Sicurezza Sociale 2015, n. 15/1, pp. 25-58. [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Cook, D.; Cohen, L. A Community Resilience Approach to Reducing Ethnic and Racial Disparities in Health. American Journal of Public Health 2005, 95, (12), pp. 2168-2173.

- Durkheim, E. De la division du travail social. Alcan: Paris, 1893.

- European Union. Official Journal of the European Union, 2020. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2020:193:FULL&from=EN.

- Eurostat. Struttura della popolazione e invecchiamento. Eurostat: Lussemburgo, 2022.

- Ferrera, M. Modelli di solidarietà. Politica e riforme sociali nelle democrazie. Il Mulino: Bologna, 1993.

- Franzini, M. Redistribuire non basta. Politiche pre-distributive per una società più giusta e meno diseguale. Social Cohesion Papers 2022, 4/2022.

- Frigerio, I.; Carnelli, F.; Cabinio, M.; De Amicis, M. Spatiotemporal Pattern of Social Vulnerability in Italy. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 2018. Retrieved from https://boa.unimib.it/bitstream/10281/198072/1/spatiotemporal_pattern_svi_italy.pdf.

- Giardiello, M.; Capobianco, R. Le contraddizioni e i paradossi della mobilità giovanile italiana. Studi di Sociologia 2021, 1, pp. 83-100.

- Giardiello, M.; Capobianco, R. Può la mobilità determinare un cambiamento sociale? Il caso studio dei giovani calabresi. Meridiana: rivista di storia e scienze sociali 2022, 103, (1), Roma: Viella, pp. 205-230.

- Gist, R.; Lubin, B. Psychosocial aspects of disasters. Wiley: Toronto, 1989.

- Governa, F.; Salone, C. Territories in Action, Territories for Action: The Territorial Dimension of Italian Local Development Policies. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2004, 28, (4), pp. 796-818. [CrossRef]

- Grignoli, D. Le developpment du locale au Molise. In Development local en Italie. Le cas du Molise Grignoli, D.; Mancini, A.; Tarozzi, A. (eds). L’Harmattan: Paris, 2013.

- Grignoli, D. Welfare percorsi di innovazione. In Welfare rights e Community Care. Rischi e opportunità del vivere sociale Barba, D; Grignoli, D. (eds) Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane: Napoli, 2017.

- Grignoli, D; Boriati, D. Sovrapposizioni di disuguaglianza e percorsi educativi. Un’esperienza nell’era del Covid. Filosofia morale 2023, 3/2023, pp. 145-158. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, P. Resilience in families and communities: Latin American contributions from the psychology of liberation. Family Journal Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families 2002, 1, (3), pp. 334-343. [CrossRef]

- Inapp. Una ripresa a tempo parziale. Istituto Nazionale per le analisi delle politiche pubbliche: Roma, 2023.

- Istat. Le misure della vulnerabilità. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, 2020.

- Istat. Report previsioni della popolazione residente e delle famiglie. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, 2021.

- Istat. Indicatori demografici. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, 2022a.

- Istat. Popolazione residente. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, 2022b.

- Istat. Benessere equo e sostenibile. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Roma, 2023.

- Kendra, J.; Wachtendorf, T. Elements of resilience after the World Trade Center disaster: reconstituting New York City’s Emergency Operations Centre, Disasters 2003, 27, (1), pp. 37-53. [CrossRef]

- Lavanco, G.; Novara, C. Disastri, catastrofi ed emergenze: analisi dei maggiori contributi in Psicologia dei disastri. In Comunità e globalizzazione della paura Lavanco G. (eds) FrancoAngeli: Milano, 2003.

- Malaguti, E. Educarsi alla resilienza. Come affrontare crisi e difficoltà e migliorarsi. Erickson: Trento, 2005.

- Mahmoudi Farahani, L. The value of the sense of community and neighbouring. Housing, theory and society 2016, 33, (3), pp. 357-376. [CrossRef]

- Martini, E. R.; Torti, A. Fare lavoro di comunità. Carocci: Roma, 2005.

- McMillan, D. W.; Chavis, D. M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology 1986, 14, (1), pp. 6-23. [CrossRef]

- Messia, F.; Venturelli, C. Il welfare di prossimità: Partecipazione attiva, inclusione sociale e comunità. Erickson: Trento, 2015.

- 57. Mijarc. The future of Rural Youth, 2003. Retrieved from https://www.saltoyouth.net/downloads/4-17-1251/FutureOfRuralYouth_MIJARC.pdf.

- Mugnano, S.; Olori, D.; Mela, A. Territori vulnerabili. Verso una nuova sociologia dei disastri italiana. FrancoAngeli: Milano, 2017.

- Neal, Z. Making Big communities small: using network science to understand the ecological and behavioral requirements for community social capital. American Journal of Community Psychology 2015, 55, (3-4), pp. 369-380. [CrossRef]

- Norris, F. H.; Stevens, S. P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K. F.; Pfefferbaum, R. L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology 2008, 41, pp. 127-150. [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Smith, A. What is a disaster? Anthropological perspectives on a persistent question. Routledge: New York, 1999.

- Openpolis. Le aree interne, tra spopolamento e carenza di servizi. Fondazione Openpolis: Roma, 2023.

- Park, R. E. Human Communities: The City and Human Ecology. Free Press: Glencoe, 1952.

- Park, R. E., The city: Suggestions for the investigation of human behavior in the urban environment. In The city Park, R. E.; Burgess, E. W.; McKenzie, R. D. (Eds.) University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1967.

- Paton, D.; Smith, L.; Millar, M. Responding to hazard effects: promoting resilience and adjustment adoption. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 2001, Autumn, pp. 47-52.

- Pierucci, P.; Serio, M. Modalità di coping di fronte alla pandemia. Sociologia dei disastri e resilienza di comunità. Salute e Società 2021, 3/2021, pp. 191-215. [CrossRef]

- Pugliese E. In Spopolamento, stipendi bassi e pochi servizi. L’emigrazione in Italia diventa un problema anche ambientale D’Alessandro J. Repubblica, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.repubblica.it/green-and-blue/2023/02/16/news/spopolamento_stipendi_bassi_servizi_ambiente_aree_interne_borghi_pnrr-388142884/.

- Putnam, R. D. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. In Culture and Politics. A Reader; Crothers, L.; Lockhart, C. (eds). Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2000.

- Ranci, C., Fenomenologia della vulnerabilità sociale. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia 2002, 4/2022, pp. 521-552. [CrossRef]

- Ranci, C. Tra vecchie e nuove disuguaglianze: la vulnerabilità nella società dell’incertezza. La Rivista delle Politiche Sociali 2007, 4, pp. 111-127.

- Rockström, J.; Norström, A. V.; Matthews, N.; Biggs, R.; Folke, C.; Harikishun, A.; Huq, S.; Krishnan, N.; Warszawski, L.; Nel, D. Shaping a resilient future in the response to COVID-19. Nature Sustainability 2023, 8, pp. 897-907. [CrossRef]

- Sarason, S. B. The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. Brookline Books: Brookline, 1974.

- Simmel, G. Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben. Hofenberg, 1903.

- Sonn, C. C.; Fisher, A. T. Sense of community: community resilient responses to oppression and change. Journal of Community Psychology 2002, 26, (5), pp. 457-472.

- Stiglitz, J.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. The measurement of economic performance and social progress revisited (Reflections and Overview). Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Paris, 2009.

- Teti, V. Ritorni al Sud nel tempo del Covid. Scienze del Territorio – Special Issue Abitare il Territorio al tempo del Covid 2020, pp. 63-71. [CrossRef]

- Tobin, G. A.; Whiteford, L. M. Economic Ramifications of Disaster: Experiences of Displaced Persons on the Slopes of Mount Tungurahua, Ecuador. Proceedings of the Applied Geography Conferences 25 2002, Binghamton.

- Tönnies, F. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. Fues: Leipzig, 1887. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P. Deprivation. Journal of Social Policy 1987, 16, pp. 125-146. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Program. Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations 2015. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html.

- United Nations. Multidimensional vulnerability index. Potential development and uses. United Nations 2021. Retrieved from https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/multidimensional_vulnerability_indices_0.pdf.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. UNISDR terminology on disaster risk reduction. United Nations: Geneva, 2009.

- Weichselgartner, J. Disaster mitigation: The concept of vulnerability revisited. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 2001, 10, (2), pp. 85-95.

- Wirth, L. The City. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1925.

- Wisner, B.; Blaikie P.; Cannon, T.; Davis, I. At risk: Natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters. Routledge: London, 2004.

- Zamagni, S. Economia civile e nuovo welfare. Italianieuropei 2011, n. 3, pp. 26-33.

- Zimmerman, M. A. Empowerment Theory & Adolescent Resilience. Proceedings of the European Association for Research on Adolescence 2004.

Notes

| 1 |

For example young people who graduate in the South live more frequently in the Inner Areas than those in the Centre and North. We are talking about 31% compared to 14.3% and 8.4% [4]. |

| 2 |

From its origins sociology has been interested in the notion of Community. In particular, Tönnies [78], Simmel [73], Wirth [84], Park [63-64] classified community and society. Community is characterized as being a typically rural, close connections, morally superior; while society is presented as urban, weak and depraved relationships. Over time, other social scientists have been involved in topics stating that Communities need a «spatial or demographic anchor around which relationships and social capital can coalesce» [59] (p. 376). |

| 3 |

The social dimension explains conditions and processes of individuals and the entire population. Here, the conditions refer to health aspects, social interactions, population distribution and demography and, to an extent, dwellings [7]. Furthermore, indicators used to create the global drought risk map of social vulnerability are: - Rural population (% of total population) - Literacy rate (% of people ages 15 and above) - Improved water source (% of rural population with access) - Life expectancy at birth (years) - Population ages 15-64 (% of total population) - Refugee population by country or territory of asylum (% of total population) - Government Effectiveness Country Negative 2013 WGI [81]. |

| 4 |

The concept ‘‘vulnerability’’ is used in different research contexts. |

| 5 |

The concept is clearly related to social deprivation, the earliest studies of which date back to the 1980s and can be traced to the Anglo-Saxon world [79]. |

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

See, in this regard, also the reference to Generative or Civic Welfare. See Zamagni [86]. |

| 8 |

The Index of Vulnerability by Territorial Fragility (IVFT) measures the «health status of the territory» according to the natural risk related to the characteristics of the territory [45] (p. 60). Also, see the Index of Countering Social and Material Vulnerability (ICVSM) covers social welfare assistance carried out by public bodies and in particular municipalities [45] (p. 62). |

| 9 |

Among Inner Areas, there is the province of Campobasso, which could experience a loss of 15% to 20% of younger residents [48]. Link to study: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2022/07/FOCUS-AREE-INTERNE-2021.pdf. Accessed: 06/23/2023. It should be noted, however, that during the pandemic period there was «a return to the countries of origin: from the North to the South of Italy, but also from urban centres to villages, from the coast to the interior, from the plains to the mountains». See, on the topic, Teti [76]. |

| 10 |

See, in this regard, the topic of territorial inequalities [19]. |

| 11 |

The concept of social cohesion is complicated to define. The term was first used by Durkheim in his work The Division of Social Labor. In contemporary societies, social cohesion, «implies: ensuring a sufficient level of social security protection; promoting employment, training and workers’ rights; protecting social groups at risk; promoting equal opportunities; striving against exclusion and discrimination; and promoting the social inclusion of immigrant populations». It is therefore a multidimensional issue that intertwines those concerning various topics [70]. |

| 12 |

See The Straburg Declaration (January 2014). In this framework, Adam Smith argued that collective welfare can be fostered only if individual interest and market functioning are controlled by precise institutional rules. |

| 13 |

See the reference to ISTAT’s BES - Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia, which consists of 12 fundamental domains ( https://www.istat.it/it/files//2018/04/12-domini-commissione-scientifica.pdf) that are all-inclusive of all spheres that contribute to well-being in a holistic sense: health, education and training, work and life-time balance, social relations, economic well-being, politics and institutions, security subjective well-being, landscape and cultural heritage, environment innovation, research and creativity, and quality of services. See: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2023/04/Bes-2022.pdf. Accessed: 06/23/2023. |

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

See also the Permanent Population Census for the Molise Region, according to which the census population in Molise as of Dec. 31, 2019, was 300,516, a reduction of 3,274 inhabitants (-10.8 per thousand) from the previous year and 13,144 inhabitants (-5.3 per thousand on average each year) from the 2011 Census. |

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

The semi-structured questionnaire – through which it is possible to suggest some open-ended questions with the aim of giving greater freedom of response [25] – constructed ad hoc for the research, consisting of a total of 66 questions divided into 5 different thematic areas (socio-anagraphical; perception of relationship with the family, friendships, territory and well-being/quality of life; perception and motivations of depopulation; behaviours enacted; role of policies and welfare to counter the phenomenon). |

| 18 |

See Banfiedl [10] and the concept of «amoral familism» for the “familist welfare”. |

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

According to ISTAT, at the Italian level, «the share of the population reporting volunteer activity returns to growth, standing at 8.3% in 2022 (it was 7.3% in 2021); however, the increase does not allow to a return to pre-pandemic levels (9.8% in 2019)». In BES 2022 [49], Chapter 5 - Social Relations, available at the link: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2023/04/5.pdf, p. 134. Accessed: 18/10/2023. |

| 21 |

Framework Law on Volunteering. Law August 11, 1991, No. 266 - Art. 1, Paragraph 1. |

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

In addition to the paper by Rockström et al., [71] see also the work of Bodin et al. [15]. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).