Submitted:

16 November 2023

Posted:

17 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Data Sources and Measurement

Data Analysis

- Percentage of difference in immunization coverage compared to pre-pandemic coverage: coverage of the year under review divided by the 2019 coverage, minus one and multiplied by 100. To calculate a percentage difference in the few countries where coverage was null in 2019 but non-zero in 2022, coverage in 2019 was set to 1.

- Number of zero-dose (ZD) children: number of surviving infants (aged 0-11 months) for a given year (from the United Nations (UN) Population Estimates 2022 revision) [17] minus the number of children vaccinated with DTP1 during the same year.

- Number of un-immunized children for vaccines other than DTP: number of target population for a given year and antigen (from UN Population Estimates 2022 revision), minus the number of children vaccinated with the related vaccine during the same year.

- Number of under-immunized children: number of children vaccinated with the last dose of a given vaccine minus the number of children vaccinated with the first dose of the said vaccine.

- Percentage of ZD children: Number of zero-dose children divided by surviving infants for the same period, multiplied by 100.

3. Results

Overview of Data Reported

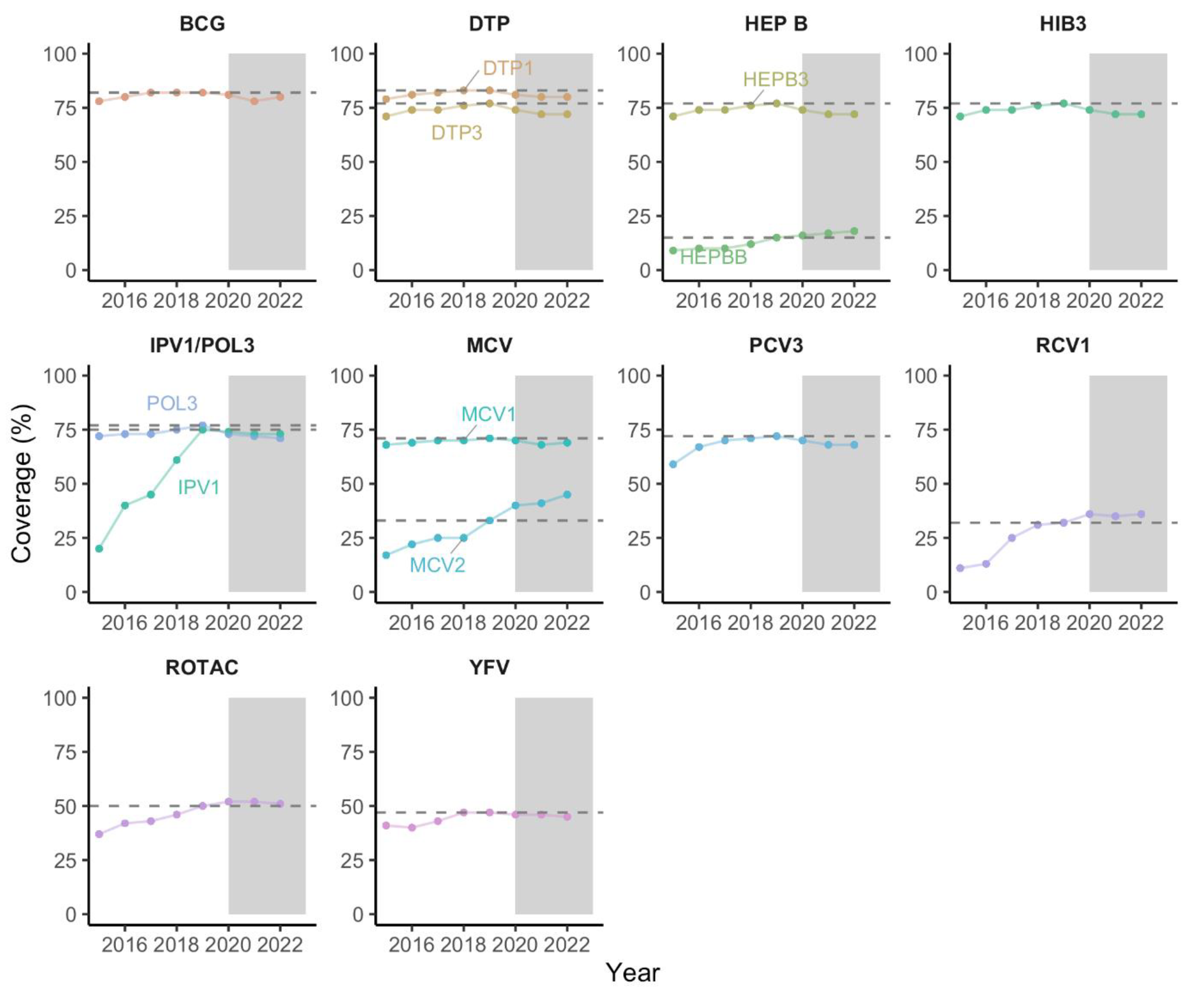

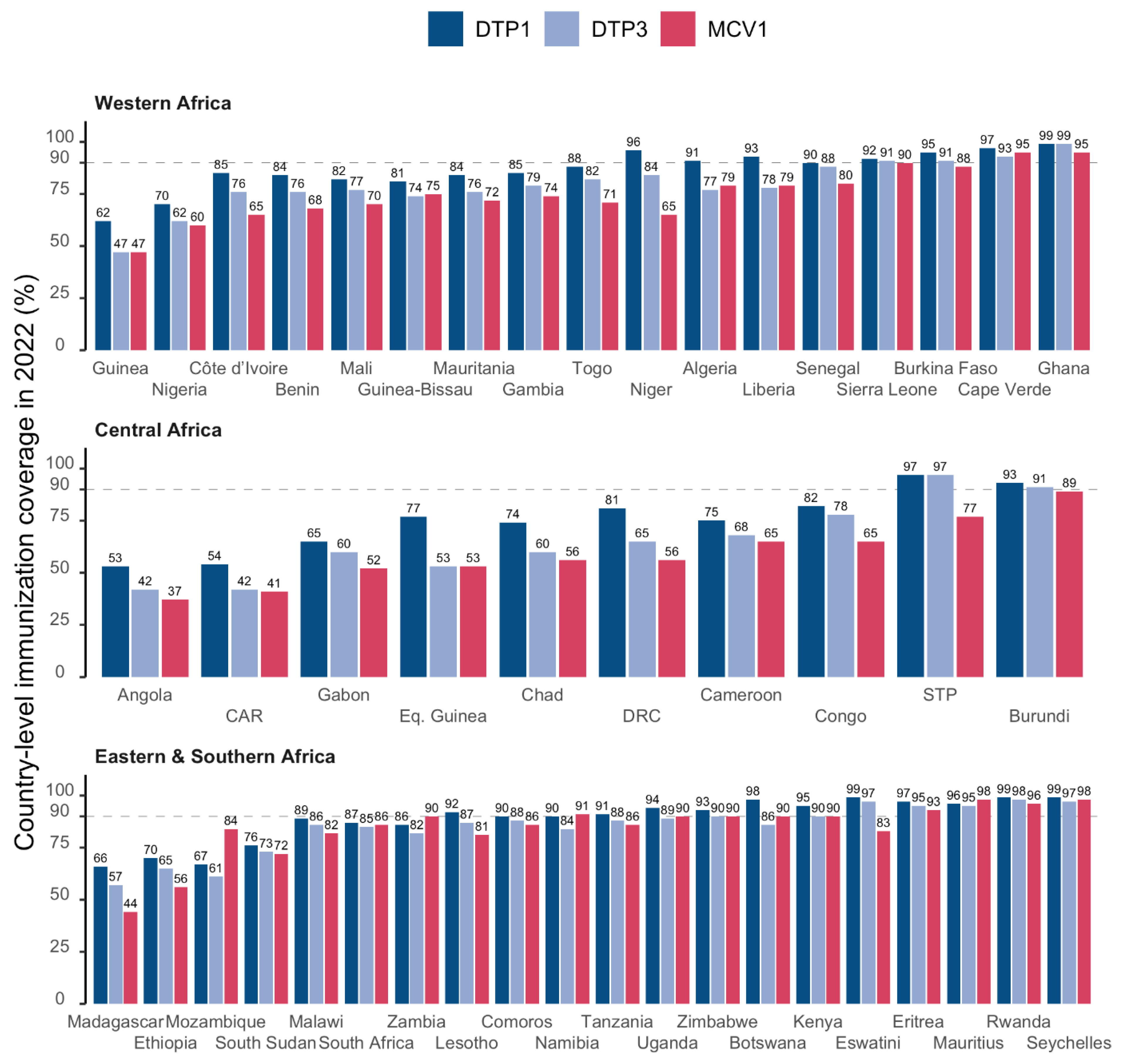

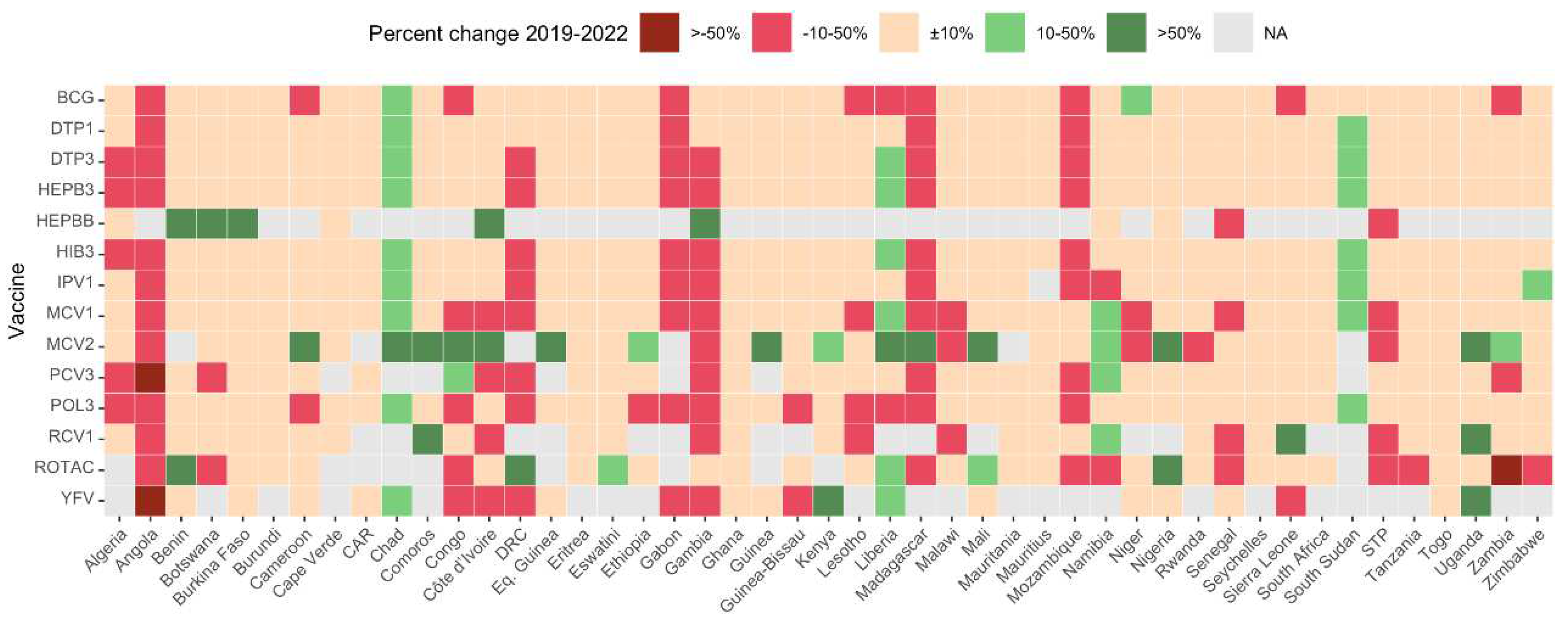

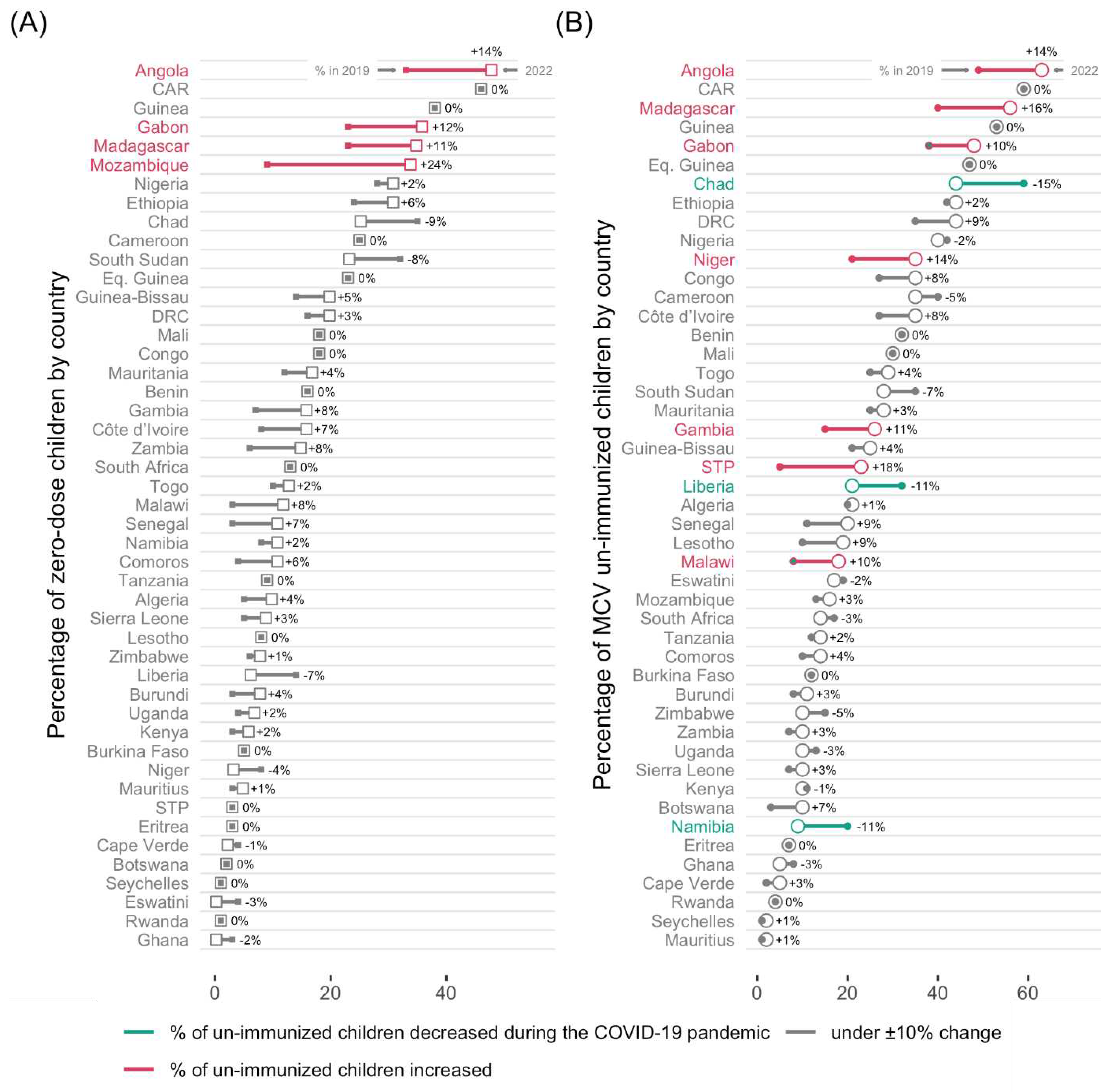

Immunization Coverage Trends

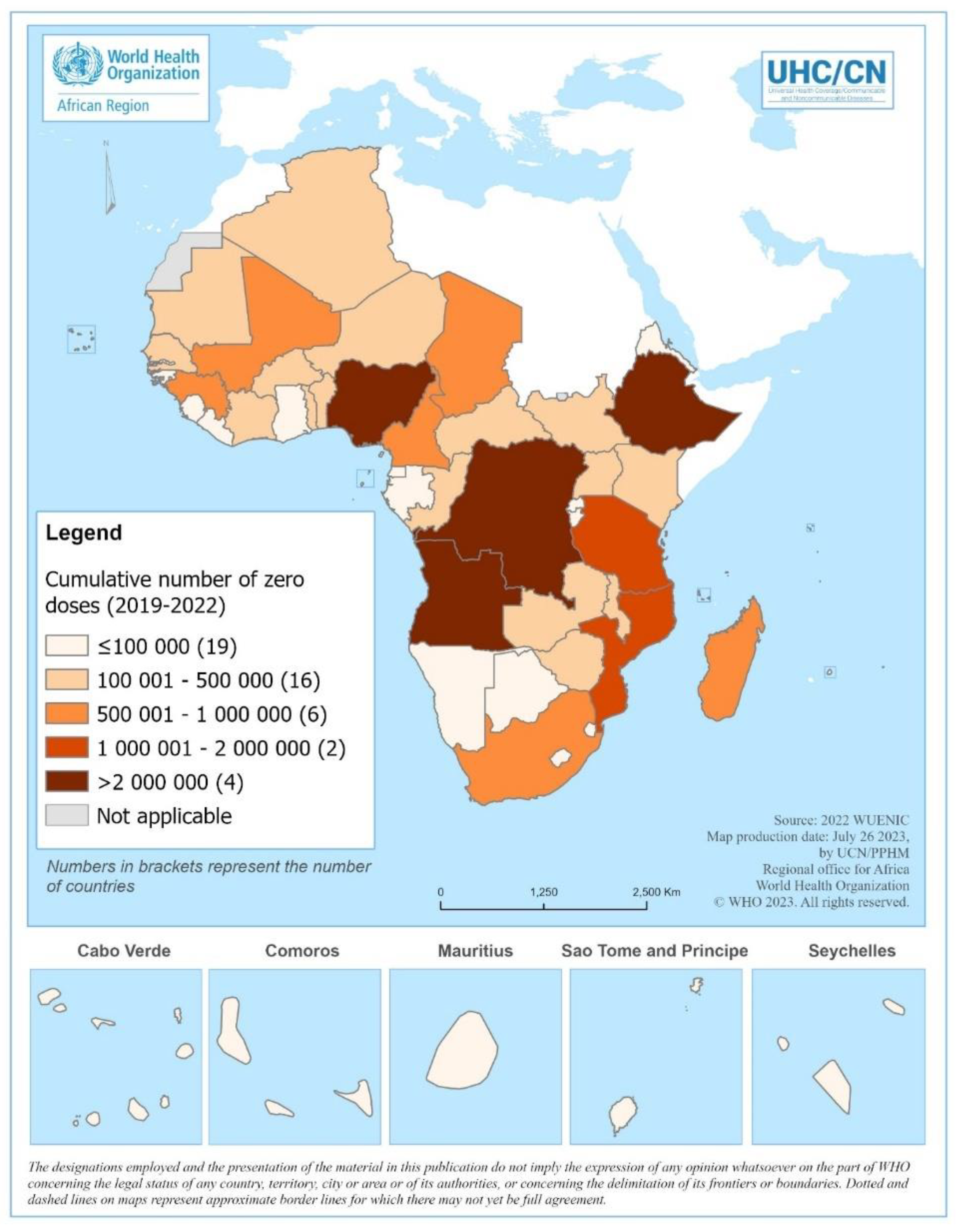

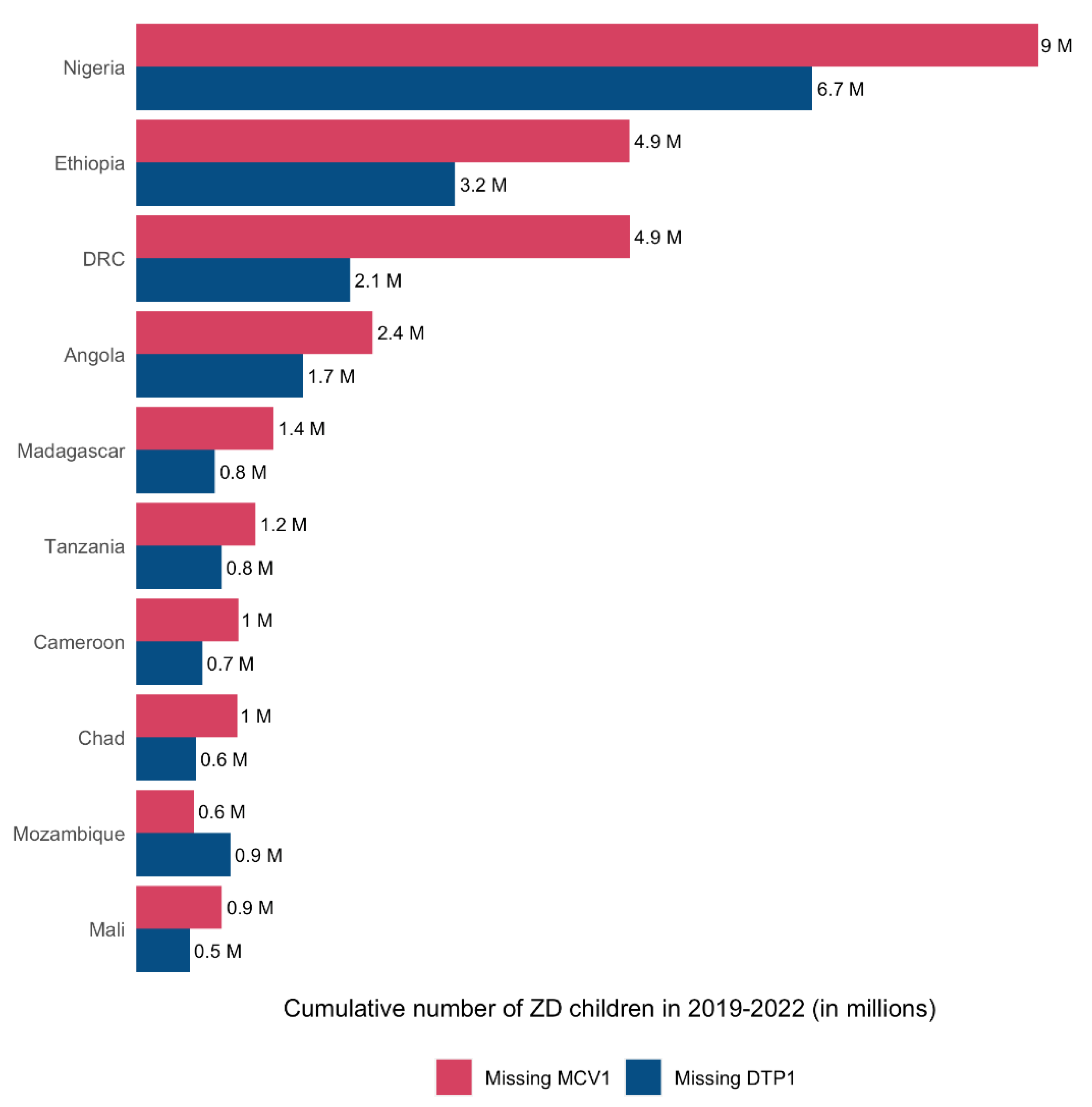

Un- and Under-Immunized Children

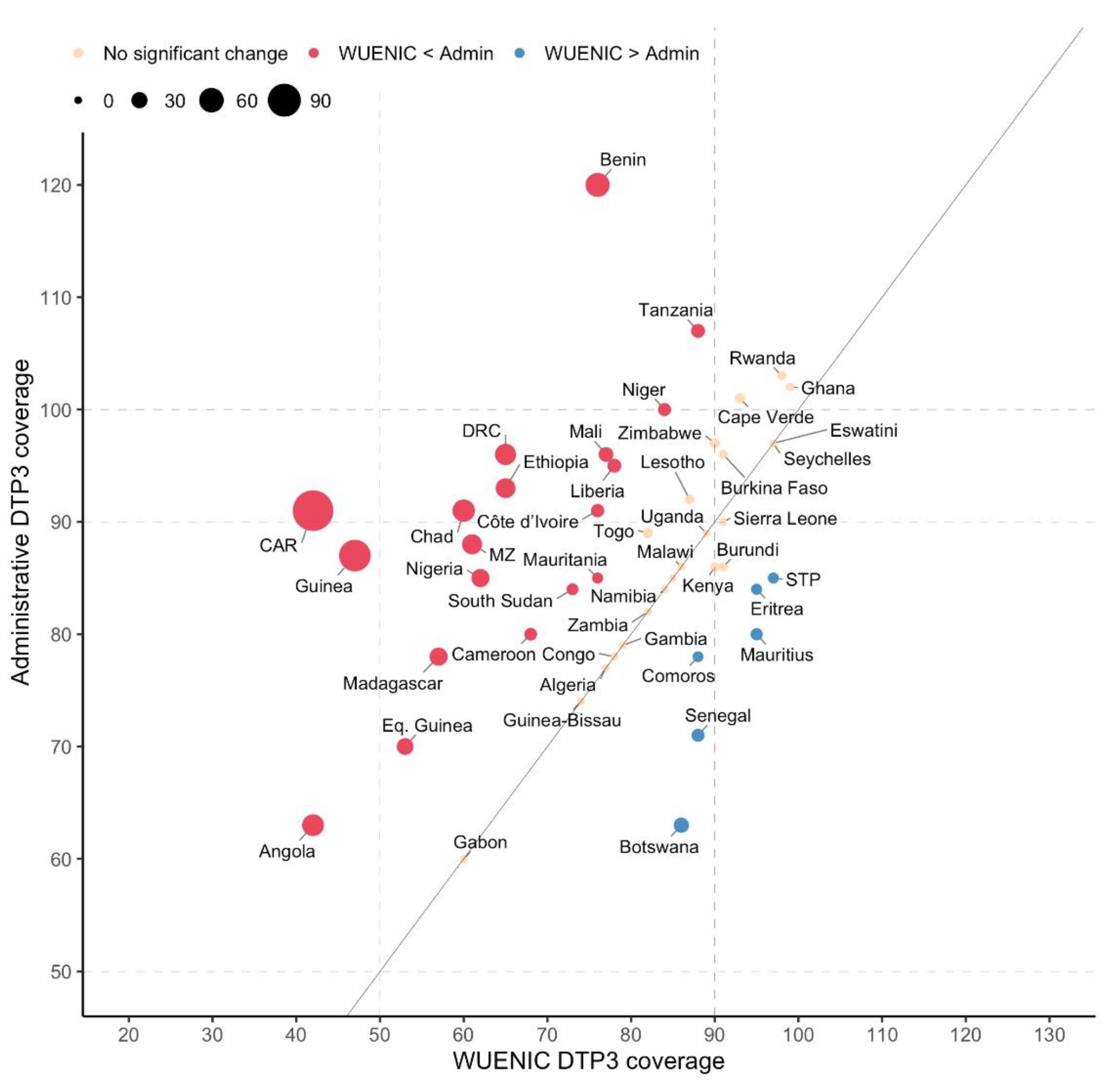

WUENIC and Administrative Coverage Data Comparison

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaythorpe, K.A.; Abbas, K.; Huber, J.; Karachaliou, A.; Thakkar, N.; Woodruff, K.; Li, X.; Echeverria-Londono, S.; Ferrari, M. Impact of COVID-19-related disruptions to measles, meningococcal A, and yellow fever vaccination in 10 countries. Elife 2021, 10, e67023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masresha, B.G.; Luce Jr, R.; Shibeshi, M.E.; Ntsama, B.; N’Diaye, A.; Chakauya, J.; Poy, A.; Mihigo, R. The performance of routine immunization in selected African countries during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Pan African Medical Journal 2020, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidu, Y.; Di Mattei, P.; Nchinjoh, S.C.; Edwige, N.N.; Nsah, B.; Muteh, N.J.; Ndoula, S.T.; Abdullahi, R.; Zamir, C.S.; Njoh, A.A.; et al. The Hidden Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Childhood Immunization Coverage in Cameroon. Vaccines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, O.A.; Olatunji, M.B.; Omotajo, O.R.; Ikwunne, O.I.; Babatunde, A.M.; Nihinlola, E.T.; Patrick, G.F.; Dairo, D.M. Impact of COVID-19 on routine immunization in Oyo State, Nigeria: trend analysis of immunization data in the pre-and post-index case period; 2019-2020. Pan African Medical Journal 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. About WHO: Regional Office for Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/countries (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Impouma, B.; Mboussou, F.; Farham, B.; Wolfe, C.M.; Johnson, K.; Clary, C.; Mihigo, R.; Nsenga, N.; Talisuna, A.; Yoti, Z. The COVID-19 pandemic in the WHO African region: the first year (February 2020 to February 2021). Epidemiology & Infection 2021, 149, e263. [Google Scholar]

- Mbow, M.; Lell, B.; Jochems, S.P.; Cisse, B.; Mboup, S.; Dewals, B.G.; Jaye, A.; Dieye, A.; Yazdanbakhsh, M. COVID-19 in Africa: Dampening the storm? Science 2020, 369, 624–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Singh, S.K.; Sharma, L.; Dwiwedi, M.K.; Agarwal, D.; Gupta, G.K.; Dhiman, R. Magnitude and causes of routine immunization disruptions during COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2021, 10, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, L.L.; Gurung, S.; Mirza, I.; Nicolas, H.D.; Steulet, C.; Burman, A.L.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Sodha, S.V.; Kretsinger, K. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on vaccine-preventable disease campaigns. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022, 119, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shet, A.; Carr, K.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Sodha, S.V.; Prosperi, C.; Wunderlich, J.; Wonodi, C.; Reynolds, H.W.; Mirza, I.; Gacic-Dobo, M. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on routine immunisation services: evidence of disruption and recovery from 170 countries and territories. The Lancet Global Health 2022, 10, e186–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Reaching zero-dose children. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/strategy/phase-5-2021-2025/equity-goal/zero-dose-children-missed-communities (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- World Health Organization. The big catch-up: an essential immunization recovery plan for 2023 and beyond. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240075511 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- World Health Organization Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations- (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Process. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/global-monitoring/who-unicef-joint-reporting-process (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Burton, A.; Monasch, R.; Lautenbach, B.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Neill, M.; Karimov, R.; Wolfson, L.; Jones, G.; Birmingham, M. WHO and UNICEF estimates of national infant immunization coverage: methods and processes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2009, 87, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.; Kowalski, R.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Karimov, R.; Brown, D. A Formal Representation of the WHO and UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage: A Computational Logic Approach. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e47806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2022. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, M.; Sanderson, B.; Robinson, L.J.; Homer, C.S.E.; Pomat, W.; Danchin, M.; Vaccher, S. Impact of COVID-19 on routine childhood immunisations in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. PLOS Global Public Health 2023, 3, e0002268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, M.O.C.; Badur, S.; Romano-Mazzotti, L.; Friedland, L.R. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine immunization. Annals of Medicine 2021, 53, 2286–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G. Routine Vaccination Coverage—Worldwide, 2022. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2023, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Immunization coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- World Health Organization. WHO South-East Asia Region lauds countries for routine immunization coverage scale-up, says accelerated efforts must continue. Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/detail/18-07-2023-who-south-east-asia-region-lauds-countries-for-routine-immunization-coverage-scale-up--says-accelerated-efforts-must-continue. (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Borba, R.C.; Vidal, V.M.; Moreira, L.O. The re-emergency and persistence of vaccine preventable diseases. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2015, 87, 1311–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IntraAction. Global rise in vaccine-preventable diseases highlights urgent actions needed to save lives and alleviate future suffering. Available online: https://www.interaction.org/blog/global-rise-in-vaccine-preventable-diseases-highlights-urgent-actions-needed-to-save-lives-and-alleviate-future-suffering/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Adegboye, O.A.; Alele, F.O.; Pak, A.; Castellanos, M.E.; Abdullahi, M.A.S.; Okeke, M.I.; Emeto, T.I.; McBryde, E.S. A resurgence and re-emergence of diphtheria in Nigeria, 2023. Therapeutic Advances in Infection 2023, 10, 20499361231161936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogan, D.; Gupta, A. Why Reaching Zero-Dose Children Holds the Key to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Vaccines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. The Zero-Dose Child: Explained. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/zero-dose-child-explained (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- O’Brien, K.L.; Lemango, E. The big catch-up in immunisation coverage after the COVID-19 pandemic: progress and challenges to achieving equitable recovery. The Lancet 2023, 402, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, E.A.; Shrestha, P.; Seth, A.; Lalika, M.S.; Azie, J.I.; Patel, R.C. Interventions to Vaccinate Zero-Dose Children: A Narrative Review and Synthesis. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, K.; Bergen, N.; Schlotheuber, A.; Sodha, S.V.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Hosseinpoor, A.R. Subnational Inequalities in Diphtheria–Tetanus–Pertussis Immunization in 24 Countries in the African Region. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2021, 99, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IQVIA Middle-East and Africa. Removing the immunization barriers for zero-dose children: How to make it work. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/locations/middle-east-and-africa/blogs/2023/02/removing-immunization-barriers-for-zero-dose-children-how-to-make-it-work. (accessed on 7 November 2023).

- World Health Organization Leave no one behind: guidance for planning and implementing catch-up vaccination. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240016514 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- World Bank blogs. How to finance “The Big Catch-Up,” allowing more children and communities to be protected from vaccine-preventable diseases. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/how-finance-big-catch-allowing-more-children-and-communities-be-protected-vaccine (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa. African leaders call for urgent action to revitalize routine immunization. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/african-leaders-call-urgent-action-revitalize-routine-immunization (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Rau, C.; Lüdecke, D.; Dumolard, L.B.; Grevendonk, J.; Wiernik, B.M.; Kobbe, R.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C. Data quality of reported child immunization coverage in 194 countries between 2000 and 2019. PLOS Global Public Health 2022, 2, e0000140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, K.; Rahimi, N.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C. Factors Limiting Data Quality in the Expanded Programme on Immunization in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Vaccine 2020, 38, 4652–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihigo, R.; Okeibunor, J.; Anya, B.; Mkanda, P.; Zawaira, F. Challenges of immunization in the African Region. The Pan African Medical Journal 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Assessing and improving the accuracy of target population estimates for immunization coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/assessing-and-improving-the-accuracy-of-target-population-estimates-for-immunization-coverage (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Ziema, S.A.; Asem, L. Assessment of immunization data quality of routine reports in Ho municipality of Volta region, Ghana. BMC Health Services Research 2020, 20, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VillageReach. Lessons Learned from a Landscape Analysis of EIR Implementations in Low- and Middle-Income Coun-tries. Available online: https://www.villagereach.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2020-EIR-Landscape-Analysis.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Momentum. Optimizing COVID-19 Vaccination Data Investments for the Future: The COVID-19 to Routine Immunization Information System Transferability Assessment. Available online: https://usaidmomentum.org/webinar-optimizing-covid-19-vaccination-data-investments-for-the-future/ (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Diallo, M.S.; Murphy, P.; Brown, D.W. Compliance of WHO and UNICEF Estimates of National Immunization Coverage (WUENIC) with Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) Criteria. Gates Open Research 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | # Surviving Children | Estimated Number of Vaccinated with DTP1 | Estimated Number of Zero-Dose Children | % Zero-Dose Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 36 995 277 | 30 763 363 | 6 231 914 | 16.8 |

| 2020 | 37 521 132 | 30 463 727 | 7 057 405 | 18.8 |

| 2021 | 38 080 516 | 30 439 539 | 7 640 977 | 20.1 |

| 2022 | 38 567 250 | 30 791 574 | 7 775 676 | 20.2 |

| Cumulative 2019-2022 | 151 164 175 | 122 458 203 | 28 705 972 | 19.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).