1. Introduction

Special health care needs

Children's health and wellbeing affect their development and adulthood. About 10% of children and adolescents have special healthcare needs [

1,

2], defined as requiring health services beyond that required by children generally due to chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions [

3] (p.138). Early problem identification and intervention have positive effects on children's, adolescents', and parents' wellbeing and health [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Effect study

In 2016-2018, we conducted a non-randomised controlled trial in preventive youth health care (PYH) to evaluate the effects of the GIZ assessment methodology (

Gezamenlijk Inschatten van Zorgbehoeften [Dutch], translated as Joint Assessment of Care Needs [

8]. GIZ supports professionals in jointly with parents and child assessing child, parental, and contextual strengths, and care needs, and deciding on follow-up actions. Compared to the control group, the GIZ group discussed parenting and contextual aspects more often, had fewer parent-reported concerns, higher parent-youth health professional agreement on concerns regarding child development and on whether or not advice was provided, and higher parental satisfaction with the consultation's content. Parents with concerns reported higher satisfaction for engagement, child-specific communication, and increased knowledge after the consultation.

Purpose of the Study

Our goal is to increase transparency in the development of the GIZ methodology, informing professionals about the rationale and different steps in the development process and consequently creating interventions with greater reproducibility. The GIZ methodology, developed through multidisciplinary consensus, is designed to help health care providers identify care needs and deliver appropriate support for children, adolescents, and families in PYH and specialized youth care settings. The methodology is intended for a broad range of providers serving children aged 0-23 and their families. To develop the method, we used a three-stage design based on Bartholomew et al.'s (2016) intervention mapping [

9], which included (a) a needs assessment through a literature review and interviews with stakeholders and focus groups with parents and adolescents; (b) an analysis of the characteristics of a suitable approach, and the development of the final assessment methodology; and (c) a pilot implementation of the GIZ methodology.

Research Context

The Dutch youth care system, including PYH and (specialised) youth care, aims to identify and care for children and parents with unmet care needs [

10,

11]. PYH is provided separately from primary care, consisting of continuous, comprehensive, and preventive child health care for children 0-18 through systematic screening, monitoring, and early detection of problems, advice and guidance, and referral if necessary [

12]. Local multidisciplinary teams provide specialised youth care for additional and complex psychosocial care needs [

13].

Mismatched Care Needs and Support

Severe mental health problems may not have increased in prevalence, but the demand for youth care in the Netherlands has grown [

14,

15]. Bot et al. (2013) found that 40% of families using specialised youth care did not have serious problems in their child's development or upbringing [

16]. Conversely, more than half of families with serious problems did not use specialised youth care, indicating that some children in need of help are not receiving it [

17,

18,

19]. This mismatch between care needs and support is particularly relevant to young children from ethnic minority groups [

20], and has a negative impact on care quality and effectiveness.

Good Assessment as a Condition for Effective Support

A collaborative and personalized assessment of wellbeing and care needs is essential for providing appropriate support to children and families [

21,

22]. Without such assessment, professionals will miss children with care needs or identify them too late. Furthermore, interventions may not be adapted to the unique preferences and care needs of children and families [

23] and opportunities to motivate and empower them may be missed [

24].

Professionals’ Need for Support in the Assessment and Decision making process

To address the mismatch between youth care use and needs, the Dutch system aims to provide personalized care [

25,

26]. Metselaar et al. (2015) define this as care that focuses on client needs, involves client participation in decision making, and requires appropriate attitudes and communication skills from practitioners [

27]. This requires professionals' support in this participatory process and for a framework and assessment approach that can help them quickly and adequately map the needs of individual children and parents [

28]. The GIZ methodology involves a joint, comprehensive, and structured assessment and shared decision-making process with the (future) parent and child to identify strengths, care needs, and support, aiming to provide families with appropriate, timely, and effective assistance while enhancing their own capabilities.

2. Methods

2.1. Stage 1: Needs Assessment

As a first step in developing the GIZ methodology, a problem and needs assessment was conducted for PYH and specialized youth care practices to identify desired outcomes for an assessment method. The assessment used three sources: a literature review, 26 semi-structured expert interviews, and four client focus groups, including three with parents and one with adolescents. The literature review was based primarily on Dutch sources, given the focus on the Dutch organisation of care. The focus groups and interviews used a topic list to explore experiences with youth care services, with 20 parents and eight teenagers participating. The assessment resulted in nine criteria for the methodology, formulated with input from an intervention advice group comprising health services researchers, PYH management, and policy advisers.

2.2. Stage 2: Development of an Assessment Methodology

After setting assessment methodology criteria, existing methods from the Netherlands and UK were inventoried. Models with the best fit were selected. The new methodology was developed based on these models. Parent and adolescent feedback provided useful additions, and twenty practitioners specializing in children and families in general and with mental health issues and disabilities tested the initial methodology design.

2.3. Stage 3: Pilot Implementation

A three-and-a-half-month study was conducted in a PYH and youth care organization to evaluate the efficacy of the newly developed assessment methodology. The pilot study evaluated client and professional satisfaction, client engagement, agreement on strengths and care needs, and asked professionals about barriers and facilitators to implementation, the methodology's added value, and usefulness in customizing care.

2.4. Pilot Research Group and Procedure

At the pilot's start, 19 YHPs (physicians and nurses) and 24 youth care professionals participated. The YHPs implemented the methodology in consultations with parents of children aged 3, 6, 11, and 14 months, 5-6 years, and young people aged 13-14. All parents and adolescents invited for preventive health consultations for the selected contact moments could participate in the study, with or without care needs. Informed consent was obtained through a letter sent in advance. Questionnaires were completed by parents, adolescents, and professionals at the end of each consultation. Satisfaction, care needs, follow-up actions and degree of client participation were measured on a 5-point scale. A T-test was used to examine differences in perception between professionals, parents, and adolescents. Descriptive analyses were conducted on linked data and supplemented by qualitative information obtained from working visits and evaluation meetings.

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1: Criteria for the Development of a New Approach

The identified key criteria from the literature review, interviews, and focus groups are presented below, divided into assessment content, process, and setting (youth care system).

3.1.1. Content Criteria

The literature review found that most screening instruments focus on specific domains of child development, while a broad perspective is needed for adequate assessment and identification of solutions [

12,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The child's well-being often depends on their parents and cannot be assessed in isolation from the care needs of parents. A broad perspective is therefore essential, as child mental health problems may reflect family dysfunction, such as domestic violence and adult mental health problems [

33]. Previous observations of consultations and interviews with professionals have shown that YHPs find it difficult to initiate a discussion on parenting and the environment in a structured way [

34]. During the interviews in this study, stakeholders recommended strengthening the analysis of a child’s situation, parents and family as well as contextual circumstances using the best evidence available related to factors influencing wellbeing. Therefore, the first content criterion is a

theoretical framework that includes the child's development, parental capacities, family, and environmental circumstances.

Assessments also tend to focus more on risks than strengths, despite growing evidence of the power of positive emotions in personal growth and development and knowledge of protective factors [

35,

36,

37]. Furthermore, interventions based on empowerment and strengthening resilience and the family’s social network were more effective than interventions that omitted these aspects [

6]. Thus, a second criterion is

a theoretical framework that identifies children's and families' strengths and emphasizes empowerment.

3.1.2. Process Criteria

Bartelink et al. (2010) [

28] noted that client participation in assessment and decision making was insufficient, making the process unilateral for professionals. Shared decision-making (SDM) between healthcare providers and clients is considered the core of patient-centred care [

38] and recommended as a good practice to increase client involvement and the quality of care [

39,

40]. Parent and youth involvement in decision making has been found to lead to more effective treatment of mental health problems [

41], better identification of risks, and improved outcomes [

42]. Active participation by parents with complex care needs also improves follow-up and outcomes [

27,

41,

43,

44], while interventions that actively involved clients have proven to be more effective than those that did not [

6] Equally, clients have increasingly reported the need to be in control of their own lives and to decide on care [

45]. Therefore,

client engagement in the assessment and decision making process was formulated as a process criterion.

In PYH practice, parents and teenagers are invited to complete surveys that include confidential questions before entering the consultation. In our study, some respondents noted that they mistrusted organisations and professionals and were cautious about sharing information in case their child could be taken from them. Conversely, other respondents appreciated their partnership with professionals and felt supported. In line with PYH and youth care guidelines, professionals should act more as a coach, guiding families and strengthening their self-determination capacities [

46,

47]. However, implementing a coaching role and family-based assessment is not straightforward. For example, professionals who treat children with long-term care needs have been seen to question how to frame their new role [

48]. Therefore,

partnership and trustful relationships was determined as a second process criterion.

Next, the literature review showed that clients often lack transparency regarding the purpose of services and assessment frameworks and have insufficient confidence in the usefulness of support [

16,

18]. This was confirmed in the focus groups, where we found that clients were poorly informed about the goals and practices of health care organisations. In response, visual tools were recommended for transparency and clarity, which can enhance understanding, memories, active participation, and decision making [

49]. Thus, the third process criterion was

transparency and clarity, including the use of visual tools.

3.1.3. Youth Care System Criteria

Four system-related criteria were determined. First, stakeholders noted the inflexibility of the youth care system, hindering a family-oriented approach that prioritizes the concerns and requirements of parents and young people [

50]. This problem led to the criterion of

a needs-led, flexible service model.

Second, cooperation among youth care professionals was found lacking. A survey of methods used in youth care organizations revealed a variety of approaches. There was a lack of transparency and continuity of care, particularly for families requiring care who interacted with multiple professionals and services [

51]. Families also reported that they often had to tell their story several times. Consequently, the

broad applicability of an assessment methodology was added as the second system criterion.

Another shortcoming of current approaches was that professionals may draw intuitive conclusions based on limited information and insufficient substantiation of decisions, resulting in prejudice, as discussed by Bartelink et al. and Munro [

52,

53]. De Kwaadsteniet (2009) demonstrated that variations in decision making can stem from different theoretical frameworks used by professionals, with and without instruments [

54]. Bartelink et al. (2010) [

28] proposed a systematic approach involving information collection, analysis, and monitoring to improve the assessment and decision-making process. This would ensure methodically established, substantiated, transparent conclusions are drawn, grounded in a strong theoretical framework with appropriate tools. The resulting system criterion was

a structured and goal-oriented approach.

Finally, stakeholders and professionals expressed the need for knowledge, skills and tools to act professionally during the assessment process. While practical tools may structure effective joint assessment with parents and child [

28], a novel approach should also be focused on changing and improving attitudes, knowledge and skills of professionals. Experienced or trained practitioners, were found to make better judgements [

55]. This led to the final system criterion:

strengthening professionals’ competencies.

In summary, based on the literature and the interviews, nine criteria for a novel assessment approach were determined, based on content, process, and system (

Table S1).

3.2. Stage 2: Development and Description of the GIZ Methodology

3.2.1. Development Methodology

The nine criteria were used to evaluate several existing assessment models, namely,

Structured Problem Analysis of Raising Kids (SPARK) [

56]

, Stevig Ouderschap [Dutch; translated as Supportive Parenting][

57]

, SamenStarten [Dutch; translated as Starting Together][

58]

, Zelfredzaamheids Matrix [Dutch; translated as Self-Sufficiency Matrix] [

59]

, Ernst-taxatiemodel [Dutch; translated as Severity Assessment Model (SAM) [

60] and the Framework for the Assessment for Children in Need and their Families (FACNF) [

61]. Two models were most promising in meeting the criteria, with some adjustments.

The FACNF was the first model. It is an analytical model developed by Horwath (2010) [

29] to comprehend the developmental needs of children, parental skills required to fulfil those needs, and family and environmental circumstances. It is based on various metatheories from Belsky (1984) [

62], Bronfenbrenner and Ceci (1994) [

63] and Sameroff (2009) [

64], and it emphasized the significance of families, social and cultural environments, and their mutual interaction on children's development. The Common Assessment Framework (CAF), modelled on the FACNF, is used in the UK by professionals in education, health, justice, police, and social services. It has proven effective in identifying children's needs and providing timely and coordinated support, while promoting collaboration among healthcare professionals [

61,

65].

The second model was the severity assessment model (SAM) developed by a community pediatric service in the region of Rotterdam [

60]. This theoretically well-grounded matrix was developed to support professionals in determining care needs based on their assessment of the nature, severity and urgency of problems.

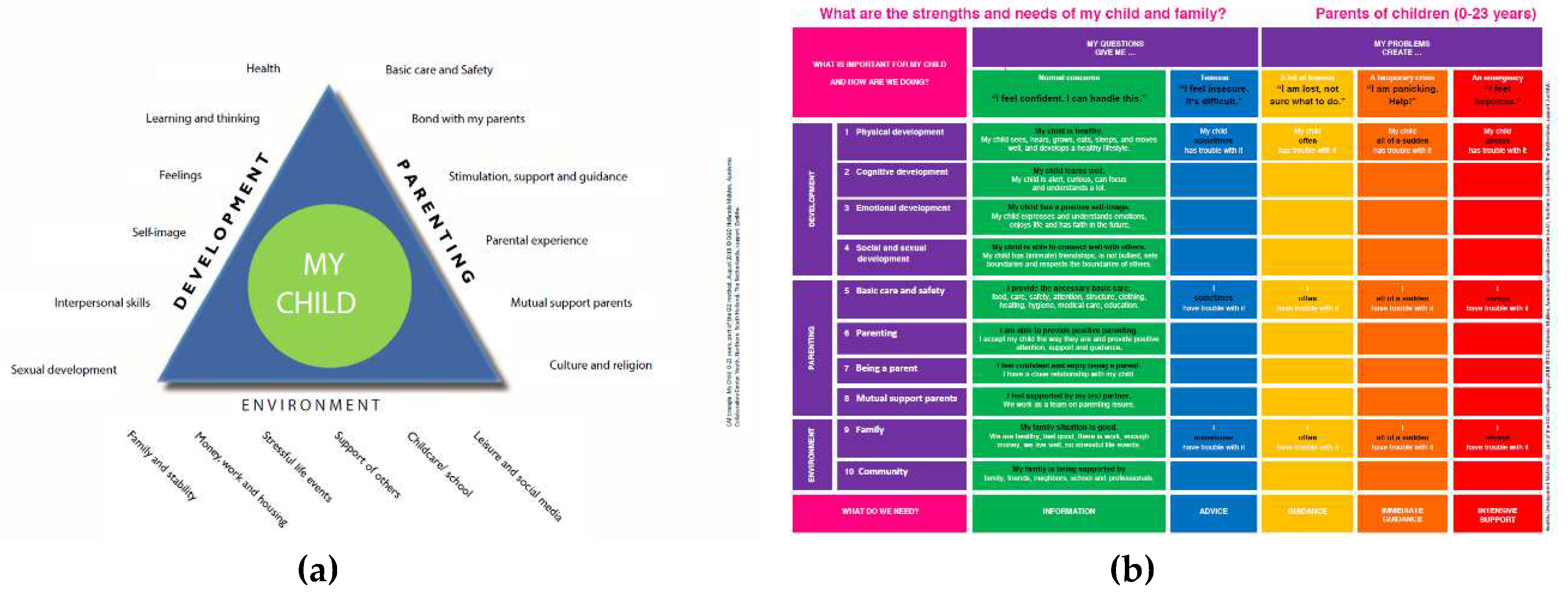

Both models fulfilled the first content criterion of a theoretical framework that considers the child's development, parental capacities, and family and environmental circumstances in a needs assessment. They also met the youth care system criteria, but several modifications were necessary to meet all criteria for an assessment approach. Transparency, engagement of clients in the assessment and decision-making process and identifying strengths and empowering children and families were the three central criteria for these modifications. To enhance transparency, visual tools were developed in lay language for use in a conversation between the client and care provider. Questions in the tools were phrased positively to activate awareness of strengths and to provide solutions to experienced problems. Adolescents and parents were addressed directly (e.g., "What are my child's and family's strengths and needs?")

To meet the criteria of the methodology, a stepped care methodology was developed. It includes initial and extended assessments, as well as a multidisciplinary approach. If additional care needs or barriers are identified, clients can opt to move to the next level. Age and target group-specific versions of the tools enable broad applicability for parents with children aged 0 to 23 and for children and young people, while various variants of the methodology ensure flexibility and wide usability in both preventive and curative care settings.

3.2.2. Description of the GIZ Methodology

The GIZ methodology, with its innovative features such as visual tools, aims to engage parents, children and young people in assessing the developmental care needs and strengths of a child and family, and jointly deciding on follow-up actions to reinforce families in their autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The GIZ triangle (

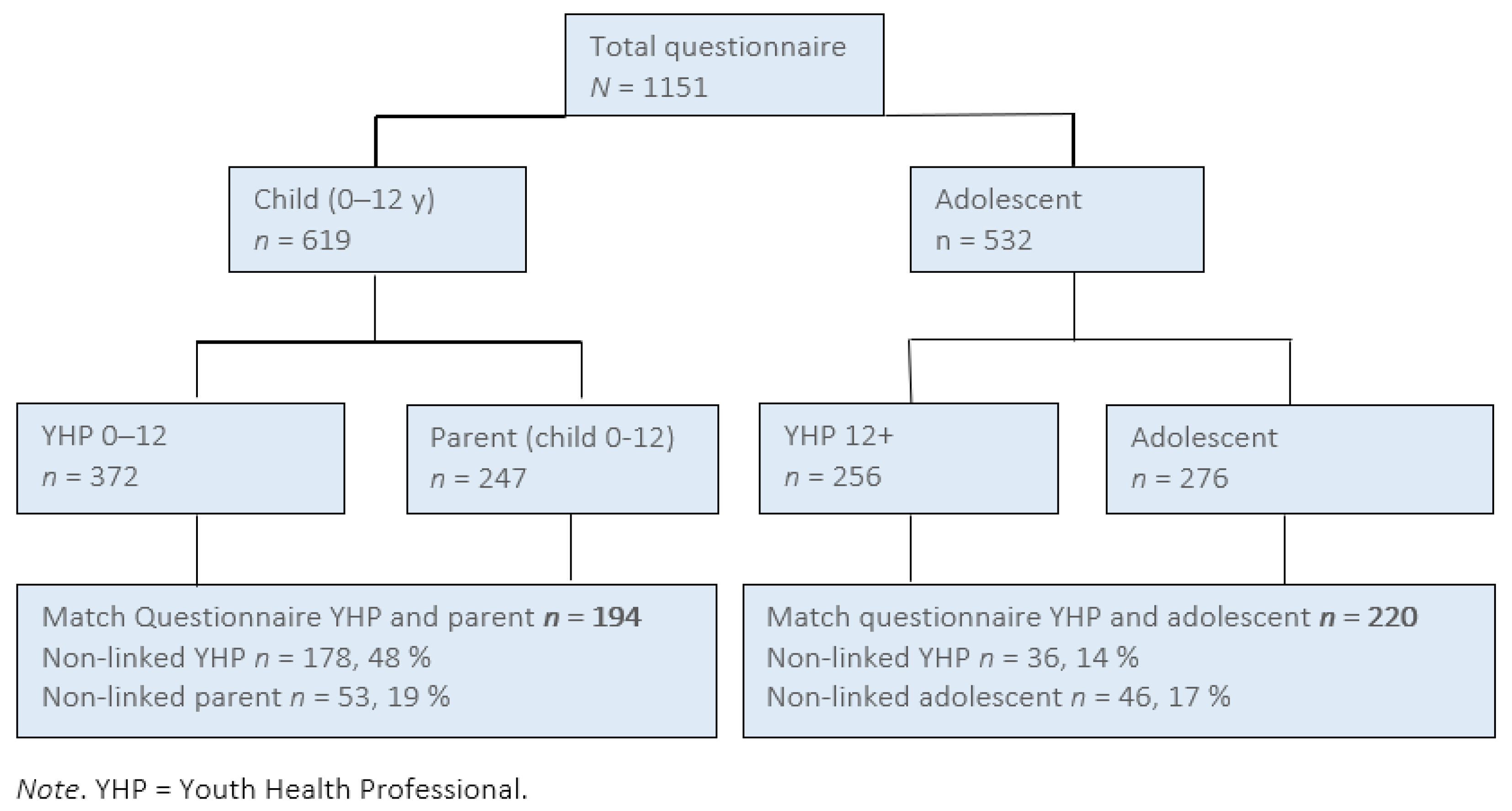

Figure 1a) and GIZ-matrix (

Figure 1b) are the two visual tools used during conversations, providing a common language for a broad target group. The GIZ has three consecutive variants (initial, extended, and multidisciplinary) enabling stepped care, and is systematically described using the TIDieR framework based on 12 features [

66].

3.3. Stage 3: Pilot Implementation of GIZ Methodology

3.3.1. Pilot in PYH

This PYH organization serves children from 0-18 years old. A total of 247 parents, 276 adolescents, 372 YHPs (aged 0–12), and 256 YHPs (aged 12+) completed the questionnaires (

Figure 2).

Parents recalled using the GIZ-matrix, while adolescents were more likely to indicate that the GIZ triangle had been used. YHPs working with adolescents used only the GIZ triangle (

Table 1). Clients and YHPs appreciated the new methodology and reported high satisfaction levels with the process, content, and results of the conversation. Parents (97%), adolescents (84%), and YHPs (80-90%) reported high agreement on child development, parenting, and the environment (

Table 1).

Satisfaction levels of parents were significantly higher when they perceived to have had a larger contribution to the GIZ consultation (p<.0001), (on process (R=. 28), content (R= .30), and result (R=. 27)). Similarly, there was a significant positive correlation for adolescents on process (R=.25, p<.0001), content (R=.21, p<.002), and result (R=.18, p<.009) when they perceived a larger contribution to the consultation. Parents and adolescents gave high evaluation scores (8.7 and 9, respectively, on a scale of 1-10) to the professionals they visited. The GIZ triangle and GIZ matrix were found to be useful and understandable tools (

Table 2).

YHPs noted that the GIZ methodology differed from their usual approach. The benefits they identified included a shared goal with parents, client engagement in joint assessment and decision-making, discussion of child development within the family and environmental context, praise and reinforcement opportunities, and better cooperation with other professionals using the same methodology. YHPs reported receiving more information on parenting and environmental issues and using GIZ tools to ask about personal issues like finances, housing, and partner relationships. They felt that the framework and their explanation why these factors were important helped parents and adolescents accept these questions and understand their impact on children's well-being.

YHPs noted some barriers and recommendations for GIZ implementation. Flexible use resulted in variation between GIZ-tools use at the beginning (50%), middle (21%), and end (20%), while the GIZ-matrix was preferred in extra care contact. Screening questionnaires and medical check-ups overlapped with GIZ. Some YHPs found the methodology uncomfortable and artificial, requiring specific communication skills. Familiarity increased with instruction meetings, supporting materials, and working visits, but a preferred methodology is needed to integrate GIZ into PYH's work process. Parents with mild cognitive impairments had difficulty using the methodology, so YHPs suggested developing a simpler version with icons (pictogram versions have been successfully used by a broad target group since 2014 [

67].

The pilot demonstrated GIZ's feasibility within preventive health consultations. On average, it took 12 minutes to implement, but this varied depending on the YHP's experience with GIZ and any emerging questions or concerns. Additional consultations were scheduled for any concerns. YHPs found GIZ helpful in tailoring care through shared agreement on strengths and care needs.

3.3.2. Pilot in Youth Care

In the Dutch care system, the youth care organization supports families when there are care needs. 17 parents and young people in youth care evaluated two visual tools with a mean score of 8.4 (out of 10), indicating improved understanding and discussion of what is essential in child development. The clients appreciated using a marker pen or chips to activate them in the assessment process. In a focus group interview with ten professionals (3.5 months after implementation), they reported that parents and young people were initially uncomfortable but eventually liked the approach and actively participated. The GIZ provided an overview of what is important in child development, attention to strengths, and added information through joint assessment. The professionals also indicated that the GIZ could be used (with some additional explanation) for clients with mild cognitive impairments. The professionals also noted some barriers, including difficulty introducing the methodology and integrating it into daily practice, and organizational changes and existing methods impeded implementation.

4. Discussion

In this study, we described the development of a joint assessment methodology, the GIZ, to identify care needs for children, adolescents, and families to deliver appropriate support. We identified nine content-, process- and system-related criteria based on literature and primary data from stakeholders and found that existing risk assessments did not meet all criteria. While the existing assessments models FACNF and SAM fit some criteria, they lacked transparency, active participation, and focus on strengths. An adapted method combining these two methods met all criteria according to the intervention advise group and auteurs.

This methodology was tested in PYH and youth care settings, and feedback was positive. Parents and adolescents appreciated the process, content, and results of the GIZ conversation. They also found their contribution valuable, and the tools used easy to understand and meaningful. YHPs and youth care professionals liked the approach because it identified care needs better, emphasized equal partnership with clients, and recognized family strengths. Implementation would require a strategy, including training, to integrate the methodology into daily practice.

The criteria that emerged from our needs assessment are in line with the literature, emphasizing the need for a broad assessment, including both needs and strengths, to support children's development. This aligns with Bronfenbrenner's bio-ecological model, which recognizes the significance of families and interactions with the social and cultural environment on children's wellbeing and development [

63]. Previous research has shown that a comprehensive evaluation of a family's strengths and care needs across multiple domains of life, as well as the use of screening tools, can facilitate integrated care [

51]. This perspective is consistent with the concept of "positive health," which has recently been introduced by Huber into Dutch health care practice under six dimensions: bodily functions, mental functions/perception, spiritual/existential dimension, quality of life, social and social participation, and daily functioning. Like the GIZ, this approach to health focuses not only on disease but also on functioning, quality of life, resilience, and self-management [

36].

Another finding of our study is the importance of engaging parents and adolescents in the assessment process. Active participation of parents and professionals is the most vital attribute of shared decision-making [

40]. Our study found that when participants felt more involved they were more satisfied with the assessment process. Families have expert knowledge of their child, which is critical to tailoring care that fits the family’s needs. Metselaar et al. (2015) also identified family participation as the primary component of needs-led youth care [

27]. Greater participation has been linked to positive changes in child behaviour, parenting stress, client satisfaction, completion rates, child safety, wellbeing, empowerment, and service coordination [

27,

41,

43,

44].

One system criterion we identified was the broad applicability of the assessment methodology. An assessment should be usable by different care providers in different settings, catering to different care needs. This could support collaboration between parents, adolescents, and professionals, as well as between professionals themselves, who work across the preventive to youth care continuum. A guiding framework with tools for mapping care needs ensures consistency in language and facilitates care transfer. Our findings are consistent with Léveillé and Chamberland's (2010) argument that the adoption of FACNF promotes cooperation among different professionals and organizations [

65].

The pilot study showed that the GIZ methodology equips professionals with skills and tools to involve parents and youth in the assessment process. Client appreciation of the GIZ's transparency, engagement in the assessment and decision-making process as well as professionals' attitudes and expectations towards the GIZ, were additional facilitators. However, YHPs and youth care professionals identified various barriers, including the integration of GIZ into their work process, insufficient professional skills, complex tools for parents and youth with language barriers, organizational turmoil, and compatibility with existing methods. Insufficient time and professionals' shared decision-making skills were consistent with the findings of Boland et al (2019)., Hayes et al. (2019), and Légaré et al (2008) [

68,

69,

70]. Facilitators observed in Boland’s study included good quality information, agreement with shared decision-making, trust and respect, and shared decision-making tools/resources. In addition, whereas in the literature shared decision-making tools often refer to decision aids that present treatment options and their advantages/disadvantages, the GIZ tools support the joint analysis of how the child and family are doing and enhance shared decision-making on what is needed. The use of pictograms and understandable language that resonates with parents and children aided this transition. This finding is consistent with Westermann's (2010) explanation of the benefits of visual tools over written or oral information [

49].

The GIZ was developed so that professionals can move from a one-directional assessment to a joint estimation of care needs and shared decision-making. With pictogram versions of the GIZ-tool, formulated in language that resonates with parents and children, the visual tools contribute to this shift. This finding is consistent with Westermann (2010) who explained the benefits of a visual tool over written or oral information) [

49].

4.1. Strengths and limitations

One of the significant strengths of our study was the developmental process, which involved a planned and systematic approach with the participation of various stakeholders from practice and research in all phases. This process was in line with the intervention mapping (IM) approach which has been used successfully in previous studies to adapt and tailor interventions [

71]. We simplified the approach and found that it helped us adapt the existing approach for the assessment of care needs. Our three-staged approach, combined with the systematic reporting tool for interventions TIDieR, resulted in a comprehensive and replicable description of our intervention. This approach is consistent with previous studies that highlight the importance of teamwork in the success of health promotion intervention planning [

71,

72].

In the Netherlands, there is a recognition procedure that aims to promote the quality and effectiveness of interventions by encouraging a process of describing and theoretically substantiating their research and development. This procedure is carried out by a national partnership of knowledge institutes [

72]. As a result, the GIZ methodology was recognised by an independent acknowledgement committee as theoretically well-founded in March 2018 and updated in 2023 [

73]. After the three-stage development process, we moved to the implementation and evaluation phase, and the results of the evaluation are described in the introduction and the article by Bontje et al. [

8].

This study is not without limitations. The quantitative data for the pilot study mentioned in this article only covers a PYH setting, whereas the GIZ is also developed for professionals in youth care. Although this pilot study highlighted the level of client satisfaction and the usability of the GIZ methodology, more evidence is needed regarding the method’s effects on identifying care needs, behaviour, and motivation among the target group.

At the start of the study, we identified nine criteria for a novel assessment methodology. Unfortunately, none of the existing methodologies in the Netherlands met these requirements at the time of writing. In the meantime, we see that multiple conversational assessment methods are characterised by a ‘broad view,’ an eye for what is going well, partnership and SDM. For example, the power of the GIZ methodology, working with visual tools, is also a functional element in the emerging methodology of positive health [

36].

4.2. Practical Implications

Since its development, The GIZ methodology has been implemented on a larger scale by a national youth knowledge centre [

11,

67]. It has recently also been developed and researched for maternity care to identify the care needs of expectant parents and families with a new-born baby. To enable the systematic use of GIZ in pregnancy, maternity care, PYH visits, childhood, adolescence, and youth care, a common framework and language should be established to facilitate communication among professionals and encourage the continuation of care for clients.

The GIZ would benefit from additional studies on its applicability and effects across different systems and populations, such as youth care and midwifery care. Also, it will be interesting to learn more about how the GIZ can contribute to shared decision-making with children and young people in vulnerable circumstances.

The findings suggest several recommendations for GIZ implementation. High-quality execution of the methodology can yield positive population-level effects, but implementation requires facilitating management, and a learning environment with continuous attention and support for professionals' knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy [

74]. Implementation should be a nonstop process based on innovation and organizational characteristics, with proper monitoring and evaluation for insights into GIZ adherence, clients and professionals satisfaction, identified care needs, interventions referred to and followed, and intervention effects [

74,

75].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Marjanne Bontje, Ria Reis and Matty Crone; Data curation, Annemarie van Dijk-van Dijk and Matty Crone; Formal analysis, Annemarie van Dijk-van Dijk and Matty Crone; Funding acquisition, Marjanne Bontje, Ria Reis and Matty Crone; Investigation, Marjanne Bontje; Methodology, Marjanne Bontje and Matty Crone; Project administration, Marjanne Bontje; Resources, Marjanne Bontje; Supervision, Ria Reis and Matty Crone; Validation, Annemarie van Dijk-van Dijk, Ria Reis and Matty Crone; Visualization, Marjanne Bontje; Writing – original draft, Marjanne Bontje; Writing – review & editing, Annemarie van Dijk-van Dijk, Ria Reis and Matty Crone.

Funding

This research was funded by ZonMw Netherlands, grant number [80-82470-98-018].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The conducted study involved research with human participants and did not fall under the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO), as it was based on the use of a non-invasive questionnaire.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank the parents, adolescents, PYH and youth care professionals, the Academic Collaborative Center, the Leiden University Medical Center, and the Public Youth Health services of GGD Hollands Midden for their partnership in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors indicate that they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. MB is developer of the methodology and wishes to confirm that the intervention is property of Hecht/GGD Hollands Midden.

References

- Boer M, van Dorsselaer S, de Looze M, de Roos S, Brons H, van den Eijnden R, et al. HBSC 2021. Gezondheid en welzijn van jongeren in Nederland. Utrecht: 2022.

- CBS Statistics Netherlands. Kerncijfers over jeugdzorg 2023. https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/85099NED/table?ts=1695052620119 (accessed September 25, 2023).

- McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, Lauver C, McManus M, Newacheck PW, et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics 1998;102:137–40. [CrossRef]

- Crouch E, Radcliff E, Brown M, Hung P. Exploring the association between parenting stress and a child’s exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Child Youth Serv Rev 2019;102:186–92. [CrossRef]

- Fagan AA. David P. Farrington, Harrie Jonkman, and Frederick Groeger-Roth (Eds.) Delinquency and Substance Use in Europe: Understanding Risk and Protective Factors Springer, 2021. International Criminology 2021;1:171–3. [CrossRef]

- MacLeod J, Nelson G. Programs for the promotion of family wellness and the prevention of child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:1127–49. [CrossRef]

- Romano E, Tremblay RE, Farhat A, Côté S. Development and prediction of hyperactive symptoms from 2 to 7 years in a population-based sample. Pediatrics 2006;117:2101–10. [CrossRef]

- Bontje MCA, de Ronde RW, Dubbeldeman EM, Kamphuis M, Reis R, Crone MR. Parental engagement in preventive youth health care: Effect evaluation. Child Youth Serv Rev 2021;120:105724. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew ELK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, Fernàndez ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning health promotion programs; an Intervention Mapping approach. 4th ed. San Francisco: 2016.

- Berg-le Clercq T, Bosscher N, Vink C. Jeugdzorg in Europa versie 2.0. Een update en uitbreiding van het rapport uit 2009 over jeugdzorgstelsels in een aantal West-Europese landen. 2012.

- Vanneste YTM, Lanting CI, Detmar SB. The Preventive Child and Youth Healthcare Service in the Netherlands: The State of the Art and Challenges Ahead. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19. [CrossRef]

- Netherlands Centre Youth Health (NCJ). Landelijk professioneel kader. Uitvoering basispakket Jeugdgezondheidszorg. 2018.

- National Government. Youth law. Staatsblad van Het Koninkrijk Der Nederlanden 2014. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stb-2014-105.html.

- Taskforce Beheersing Zorguitgaven. ‘Naar beter betaalbare zorg.’ 2012.

- Van Yperen T, Van de Maat A, Prakken J. Het groeiend jeugdzorggebruik Duiding en aanpak. Utrecht: 2019.

- Bot S, Roos S de, Sadiraj K, Keuzenkamp S, Broek A van den, Kleijnen E. Terecht in de jeugdzorg. 2013.

- Adriaanse M, Veling W, Doreleijers T, Van Domburgh L. The link between ethnicity, social disadvantage and mental health problems in a school-based multiethnic sample of children in the Netherlands. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;23:1103–13. [CrossRef]

- Nanninga M. Children’s and adolescents’ enrolment in psychosocial care: determinants, expected barriers, and outcomes. RU Groningen, 2018.

- Ten Boom A, Wittebrood K, Alink LRA, Cruyff MJLF, Downes RE, Van Eijkern EYM, et al. De prevalentie van huiselijk geweld en kindermishandeling in Nederland. 2019.

- Bevaart F, Mieloo CL, Jansen W, Raat H, Donker MCH, Verhulst FC, et al. Ethnic differences in problem perception and perceived need for care for young children with problem behaviour. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2012;53:1063–71. [CrossRef]

- De Bruyn EEJ, Ruijssenaars AJJM, Pameijer N V., Van Aarle EJM. De diagnostische cyclus: een praktijkleer. 2003.

- Poston JM, Hanson WE. Meta-analysis of psychological assessment as a therapeutic intervention. Psychol Assess 2010;22:203–12. [CrossRef]

- Hielkema M, De Winter AF, Feddema E, Stewart RE, Reijneveld SA. Impact of a family-centered approach on attunement of care and Parents disclosure of concerns: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 2014;35:292–300. [CrossRef]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation. American Psychologist 2000;55:68–78. [CrossRef]

- RMO & RVZ. Investeren rondom kinderen. Investeren rondom kinderen | Advies | Raad voor Volksgezondheid en Samenleving (raadrvs.nl) (assessed April 1, 2009).

- RMO. Ontzorgen en normaliseren 2012. Ontzorgen en normaliseren | Publicatie | Raad voor Volksgezondheid en Samenleving (raadrvs.nl). (assessed April 1, 2009).

- Metselaar J, van Yperen TA, van den Bergh PM, Knorth EJ. Needs-led child and youth care: Main characteristics and evidence on outcomes. Child Youth Serv Rev 2015;58:60–70. [CrossRef]

- Bartelink C, Ten Berge I, Van Yperen T. Beslissen over effectieve hulp. Wat werkt in indicatiestelling? 2010:1–134.

- Horwath, J. Horwath J. The Child’s World: The Comprehensive Guide to Assessing Children in Need. London: 2010.

- Integraal Toezicht Jeugd. Verantwoorde zorg aan gezinnen met geringe sociale redzaamheid in Leiden, Nota van Bevindingen Integraal Toezicht Jeugd, Utrecht: ITJ. 2012.

- McTavish JR, McKee C, Tanaka M, MacMillan HL. Child Welfare Reform: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19. [CrossRef]

- 32. Vogels AG, Crone MR, Hoekstra F, Reijneveld SA. Comparing three short questionnaires to detect psychosocial dysfunction among primary school children: A randomized method. BMC Public Health 2009;9. [CrossRef]

- Lenton S, Wettergren B, Huss G. A joint statement from the European Academy of Paediatrics, European Confederation of Primary Care Paediatricians, European Paediatric Association Union of National European Paediatric Societies and Associations. 2016.

- Bontje MCA. Van risicotaxatie naar gezamenlijk inschatten zorgbehoeften (GIZ). TSG 2013;91:374–6. [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson BL. The value of positive emotions. Am Sci 2003;91:330–5. [CrossRef]

- Huber M, Van Vliet M, Giezenberg M, Winkens B, Heerkens Y, Dagnelie PC, et al. Towards a “patient-centred” operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2016;6:1–11. [CrossRef]

- Seligman ME, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology. An introduction. Am Psychol 2000;55:5–14. [CrossRef]

- Stiggelbout AM, Van Der Weijden T, De Wit MPT, Frosch D, Légaré F, Montori VM, et al. Shared decision-making: Really putting patients at the centre of healthcare. BMJ (Online) 2012;344. [CrossRef]

- Elwyn G, Durand MA, Song J, Aarts J, Barr PJ, Berger Z, et al. A three-talk model for shared decision- making: Multistage consultation process. BMJ (Online) 2017;359. [CrossRef]

- Park ES, Cho IY. Shared decision-making in the paediatric field: a literature review and concept analysis. Scand J Caring Sci 2018;32:478–89. [CrossRef]

- Edbrooke-Childs J, Jacob J, Argent R, Patalay P, Deighton J, Wolpert M. The relationship between child- and parent-reported shared decision-making and child-, parent-, and clinician-reported treatment outcome in routinely collected child mental health services data. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016;21:324–38. [CrossRef]

- Reijneveld SA, Hielkema M, Stewart RE, De Winter AF. The added value of a family-centred approach to optimize infants’ social-emotional development: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS One 2017;12:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Chovil, N. Engaging Families in Child & Youth Mental Health: A Review of Best, Emerging and Promising Practices 2009:1–43.

- Légaré F, Thompson-Leduc P. Twelve myths about shared decision-making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:281–6. [CrossRef]

- Spijk-de Jonge M, De Lange M, Serra M, Van der Steege M, Dijkshoorn P. “Betrek mij gewoon”: op zoek naar verbeterkansen voor de jeugdhulp in het casusonderzoek ketenbreed-leren. ["Just involve me"; searching for improvement opportunities for youth care in the case study chain-wide learning.]. 2022.

- Bartelink C, Meuwissen I, Eijgenraam K. Richtlijn Samen met ouders en jeugdigen beslissen over passende hulp. [Guideline shared decision-making with parents and youth about tailored support] 2015. https://richtlijnenjeugdhulp.nl/samen-beslissen-over-passende-hulp/ (accessed September 25, 2023).

- Netherlands Centre Youth Health (NCJ). Richtlijnen Jeugdgezondheid. [Guidelines Youth Health Care] 2020. https://www.ncj.nl/richtlijnen/ (accessed September 25, 2023).

- Smith J, Swallow V, Coyne I. Involving parents in managing their child’s long-term condition-a concept synthesis of family-centered care and partnership-in-care. J Pediatr Nurs 2015;30:143–59. [CrossRef]

- Westermann GMA. Ouders adviseren in de jeugd-ggz: Het ontwerp van een gestructureerd adviesgesprek. Erasmus universiteit Rotterdam. 2010.

- Sociaal Economische Raad (SER). Jeugdzorg: van systemen naar mensen. Tien aanbevelingen voor de korte termijn. 2021.

- Nooteboom LA, Mulder EA, Kuiper CHZ, Colins OF, Vermeiren RRJM. Towards Integrated Youth Care: A Systematic Review of Facilitators and Barriers for Professionals. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 2021;48:88–105. [CrossRef]

- Bartelink C. Dilemmas in child protection: Methods and decision-maker factors influencing decision-making in child maltreatment cases. RU Groningen. 2018.

- Munro, E. Effective child protection. 3rd ed. SAGE; 2020.

- De Kwaadsteniet, LD. Clinicians as mechanics: Causal reasoning in clinical judgement and decision making. Nijmegen: Ipskamp Drukkers.; 2009.

- Spengler PM, White MJ, Ægisdóttir S, Maugherman AS, Anderson LA, Cook RS, et al. The Meta-Analysis of Clinical Judgment Project: Effects of Experience on Judgment Accuracy. Couns Psychol 2009;37:350–99. [CrossRef]

- Staal. I. SPARK 2021. SPARK | SPARK | Nederlands Jeugdinstituut (nji.nl) (accessed September 25, 2023).

- Bouwmeester M. Stevig Ouderschap 2017. (Stevig Ouderschap | Nederlands Jeugdinstituut (nji.nl)) (accessed September 25, 2023).

- Netherlands Centre Youth Health. Samen Starten 2018. SamenStarten | Nederlands Jeugdinstituut (nji.nl) (accessed September 25, 2023).

- GGD Amsterdam. Zelfredzaamheid-Matrix 2023. Zelfredzaamheid-Matrix (zelfredzaamheidmatrix.nl) (accessed September 25, 2023).

- CJG Rijnmond. Ernsttaxatie Model 2013. https://www.ncj.nl/richtlijnen/alle-richtlijnen/richtlijn/?richtlijn=9&rlpag=904.

- Health D of. The Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2001;6:4–10. [CrossRef]

- Belsky J. The Determinants of Parenting: A Process Model. vol. 55. 1984. [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-Nurture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective: A Bioecological Model. Psychol Rev 1994;101:568–86. [CrossRef]

- Sameroff A. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other. American Psychological Association; 2009. [CrossRef]

- Léveillé S, Chamberland C. Toward a general model for child welfare and protection services: A meta-evaluation of international experiences regarding the adoption of the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and Their Families (FACNF). Child Youth Serv Rev 2010;32:929–44. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ (Online) 2014;348:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Netherlands Centre Youth Health (NCJ). GIZ-methodiek 2023. https://www.ncj.nl/giz/ (accessed September 25, 2023).

- Boland L, Graham ID, Légaré F, Lewis K, Jull J, Shephard A, et al. Barriers and facilitators of pediatric shared decision-making: A systematic review. Implementation Science 2019;14. [CrossRef]

- Hayes D, Edbrooke-Childs · J, Town · R, Wolpert · M, Midgley · N. Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in child and youth mental health: clinician perspectives using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;28:655–66. [CrossRef]

- Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: Update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:526–35. [CrossRef]

- Kok, G. Practical Guideline to Effective Behavioral Change. The European Health Psychologist 2014;16:156–70.

- Netherlands Youth Institute. Databank Effective Youth Interventions 2023. https://www.nji.nl/interventies (accessed September 26, 2023).

- Bontje MCA. Interventie Gezamenlijk Inschatten van Zorgbehoeften (GIZ- methodiek). Netherlands Youth Institute 2023:1–47. Gezamenlijk Inschatten van Zorgbehoeften (GIZ-methodiek) | Nederlands Jeugdinstituut (nji.nl) (accessed September 25, 2023).

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:327–50. [CrossRef]

- Fleuren MAH, Paulussen TGWM, Dommelen P, Buuren S Van. Towards a measurement instrument for determinants of innovations. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2014;26:501–10. [CrossRef]

- Vis SA, Strandbu A, Holtan A, Thomas N. Participation and health - a research review of child participation in planning and decision-making. Child Fam Soc Work 2011;16:325–35. [CrossRef]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Meeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2012;9:25. [CrossRef]

- De Shazer S, Dolan Y, Korman H, Trepper T, McCollum. E., Berg IK. More Than Miracles: The State of the Art of Solution-focused Brief Therapy. New York: Routledge; 2007.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).