Submitted:

21 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

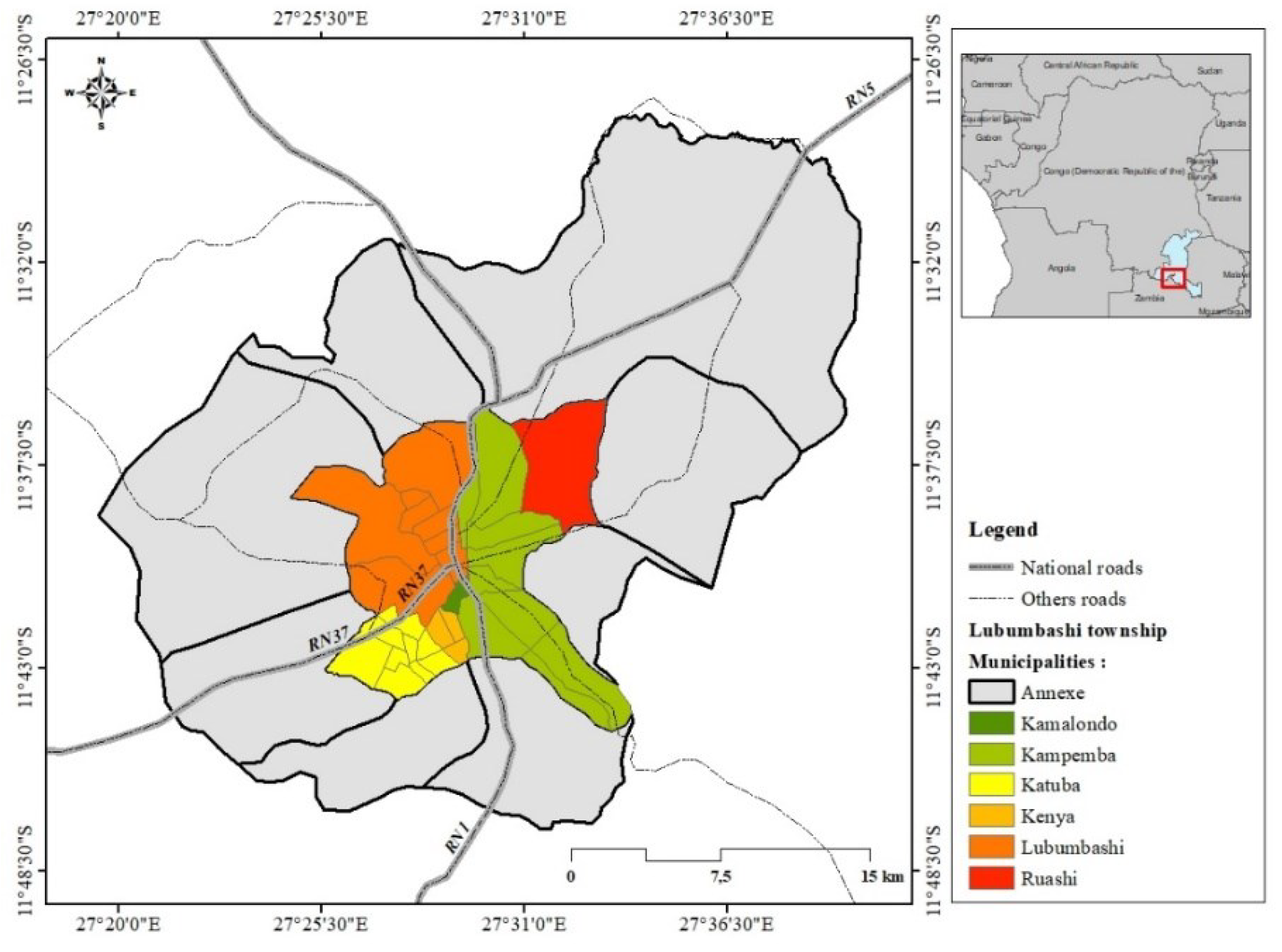

2.1. Study area: Urban zone and peri-urban zone of Lubumbashi city

2.2. Exploratory visits

2.3. Spatial analysis

2.4. Floristic data collection and analysis

3. Results

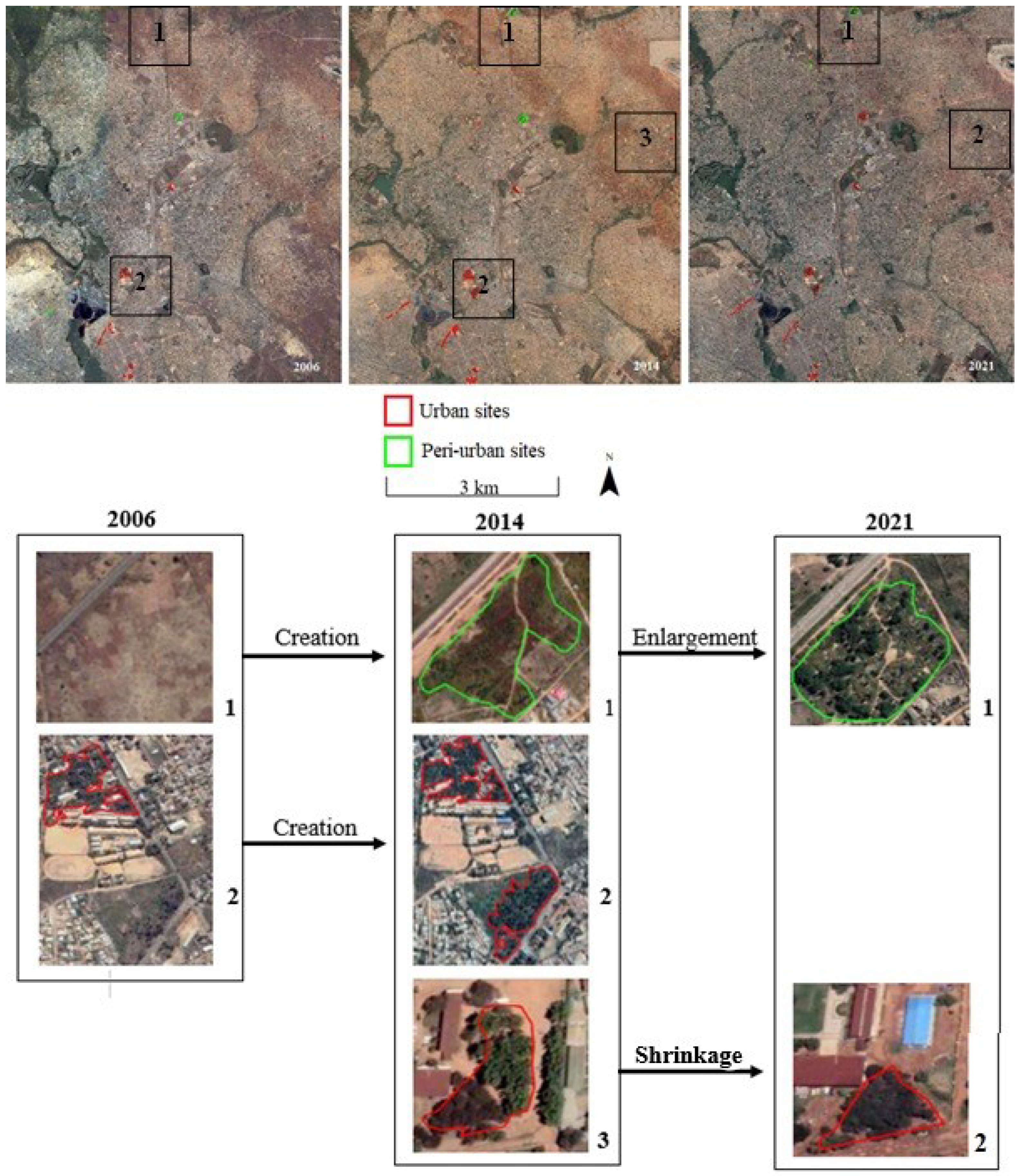

3.1. Mapping and spatial pattern of Acacia auriculiformis plantations

3.2. Flora richness and diversity under the plantation of A. auriculiformis along the urban-rural gradient of Lubumbashi city

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial pattern dynamics of A. auriculiformis and impact on phytodiversity

4.2. Implications for (peri-)urban landscape ecological restoration

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halleux, J-M. Les territoires périurbains et leur développement dans le monde : un monde en voie d’urbanisation et de périurbanisation. In Bogaert J. & Halleux J.M. (Eds). Territoires périurbains: développement, enjeux et perspectives dans les pays du sud. Les presses agronomiques de Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2015 ; 43-61.

- Antrop, M. The language of landscape ecologists and planners: A comparative content analysis of concepts used in landscape ecology. Landscape and Urban planning 2001, 55,163-173. [CrossRef]

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D.L.; & Blei, M.A. Making room for a planet of cities. Policy Focus Report, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, USA, 2011.

- Seto, K.C.; Güneralp, B.; & Hutyra, L.R.; Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109,16083–16088. [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Biloso, A.; Vranken, I.; & André, M. Peri-urban dynamics: Landscape ecology perspectives. In J. Bogaert, & J-M. Halleux (Eds.). Territoires périurbains: Développement, enjeux et perspectives dans les pays du sud. Gembloux, Belgique: Les Presses Agronomiques de Gembloux, 2015.

- Cilliers, S.S.; Cilliers, J.; Lubbe, R.; & Siebert, S. Ecosystem services of urban green spaces in African countries – perspectives and challenges. Urban Ecosystems 2013, 16, 681-702.

- Watson, V. ‘The planned city sweeps the poor away…’: Urban planning and 21st century urbanisation. Progress in planning 2009, 72, 151-193. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, M. The effects of urban patterns on ecosystem functions. International Regional Science Review 2005, 28, 168-192. [CrossRef]

- André, M.; Mahy, G.; Lejeune, P.; & Bogaert, J. Vers une synthèse de la conception et d’une définition des zones dans le gradient urbain-rural. Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement 2014, 18, 61-74.

- Bigirimana, J.; Bogaert, J.; De Cannière, C.; Lejoly, J.; & Parmentier, I.; Alien plant species dominate the vegetation in a city of sub-Saharan Africa. Landscape and Urban Planning 2011, 100, 251–267. [CrossRef]

- Bernholt, H.; Kehlenbeck, K.; Gebauer, J.; & Buerkert, A. Plant species richness and diversity in urban and peri-urban gardens of Niamey, Niger. Agroforestry Systems 2009, 77, 159–179. [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P. Alien and native species in Central European urban floras: a quantitative comparison. Journal of Biogeography 1998, 25, 155-163. [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, L. T.; Tan, H. T.; & Corlett, R. T. Invasive trees in Singapore: are they a threat to native forests? Tropical Conservation Science 2015, 8, 201-214. [CrossRef]

- Alpert, P.; Bone, E.; & Holzapfel, C. Invasiveness, invasibility and the role of environmental stress in the spread of non-native plants. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2000, 3, 52–66. [CrossRef]

- Reid, W. V. Mooney, H. A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, S. R. Chopra, K.; ... & Zurek, M. B. Ecosystems, and human well-being-Synthesis: A report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Island Press, 2005.

- Bordbar, F.; & Meerts, P.; J. Alien flora of DR Congo: improving the checklist with digitised herbarium collections. Biological Invasions 2022, 24, 939-954. [CrossRef]

- El Desouky, H. A. Muchez, P.; & Cailteux, J. Two Cu–Co sulfide phases and contrasting fluid systems in the Katanga Copperbelt, Democratic Republic of Congo. Ore Geology Reviews 2009, 36, 315-332. [CrossRef]

- Decrée, S.; Deloule, É.; De Putter, T.; Dewaele, S.; Mees, F.; Yans, J.; & Marignac, C. SIMS U–Pb dating of uranium mineralization in the Katanga Copperbelt: Constraints for the geodynamic context. Ore Geology Reviews 2011, 40,81-89. [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Cabala, K.; Halleux, J. M.; Bogaert, J.; & Munyemba, K. Caractérisation de la croissance spatiale urbaine de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD Congo) entre 1989 et 2014. Tropicultura 2018, 38, 98-108.

- Mwitwa, J.; German, L.; Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; & Puntodewo, A. Governance and sustainability challenges in landscapes shaped by mining: Mining-forestry linkages and impacts in the Copper Belt of Zambia and the DR Congo. Forest Policy and Economics 2012, 25, 19-30. [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Boisson, S.; Cabala, K.S.; Nkuku, K.C.; Malaisse, F.; Halleux, J.M.; Bogaert, J.; & Munyemba, K.F. Dynamique de l'occupation du sol autour des sites miniers le long du gradient urbain-rural de la ville de Lubumbashi, RD Congo. Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement 2020, 24, 14-27. [CrossRef]

- Useni, S. Y.; Cabala, K. S.; Nkuku, K. C.; Amisi, M. Y.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; & Munyemba, K. F. Vingt-cinq ans de monitoring de la dynamique spatiale des espaces verts en réponse à l’urbanisation dans les communes de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD Congo). Tropicultura 2017, 35,300–311.

- André, M.; Vranken, I.; Boisson, S.; Mahy, G.; Rüdisser, J. ; Visser, M. ; Lejeune, P. ; Bogaert, J. Quantification of anthropogenic effects in the landscape of Lubumbashi. In Bogaert, J. ; Colinet, G. ; Mahy, G. (Eds). Anthropisation des Paysages Katangais. Les Presses Universitaires de Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2018 ; 231–251.

- Munyemba, K.F. ; & Bogaert, J. Anthropisation et dynamique de l’occupation du sol dans la région de Lubumbashi de 1956 à 2009. E-revue UNILU 2014, 1, 3-23.

- Tambwe, N.A.; Urban agriculture, land sustainability. The case of Lubumbashi. In Bogaert J.; & Halleux J.M. (Eds). Territoires périurbains : développement, enjeux et perspectives dans les pays du sud. Les presses agronomiques de Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2015; 153-162.

- Cabala, K.S. ; Useni,S.Y. ; Munyemba, K.F. ; & Bogaert, J. Activités anthropiques et dynamique spatiotemporelle de la forêt claire dans la Plaine de Lubumbashi. In Bogaert J., Colinet G. & Mahy G. (Eds). Anthropisation des paysages katangais, Les presses universitaires de Liège, Belgique, 2018 ; 253-266.

- Klompmaker, J. O.; Hoek, G.; Bloemsma, L. D.; Gehring, U.; Strak, M.; Wijga, A. H.; den Brink, C.; Brunekreef, B.; Lebret, L.; & Janssen, N. A.; Green space definition affects associations of green space with overweight and physical activity. Environmental research 2018, 160, 531-540. [CrossRef]

- Bolund, P.; & Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecological economics 1999, 29, 293-301. [CrossRef]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; & James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landscape and urban planning 2007, 81, 167-178. [CrossRef]

- Yang,L.; Liu, N.; Ren, H.; & Wang, J. Facilitation by two exotic Acacia: Acacia auriculiformis and Acacia mangium as nurse plants in South China. Forest ecology and management 2009, 257, 1786-1793. [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala, K.S.; Kalumba, M.A.; Mwana,Y.A.; Nkuku, K.C.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K.F. Tree diversity and structure on green space of urban and peri-urban zones: the case of Lubumbashi City in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2019, 41 ,67–74. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D. M.; Macdonald, I. A. W.; & Forsyth, G. G. Reductions in plant species richness under stands of alien trees and shrubs in the fynbos biome. South African Forestry Journal 1989, 149, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- D'antonio, C. A. R. L. A.; Meyerson, & L. A. Exotic plant species as problems and solutions in ecological restoration: a synthesis. Restoration ecology 2002, 10, 703-713. [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, A. Are the ecological impacts of alien species misrepresented? A review of the “native good, alien bad” philosophy. Community Ecology 2010, 11, 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Sumi, K.; & Ise, T. Identifying the vegetation type in Google Earth images using a convolutional neural network: a case study for Japanese bamboo forests. BMC ecology 2020, 20, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; & Andre, M. Landscape ecology: a unifying discipline. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 1-2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259037085_Tropicultura_Volume_31_Number_1.

- Gong, C.; Chen J.; & Yu, S. Biotic homogenization and differentiation of the flora in artificial and near-natural habitats across urban green spaces. Landscape and Urban Planning 2013, 120 , 158-169. [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R. K.; Dogra, K. S.; Batish, D. R.; & Singh, H. P. Impact of invasive plants on the structure and composition of natural vegetation of northwestern Indian Himalayas. Weed Technology 2004, 18, 1296-1300. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3989638.

- Malaisse, F. How to live and survive in Zambezian open forest (Miombo ecoregion). Presses agronomiques de Gembloux: Gembloux, Belgium, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Kalombo, K.D. ; Evaluation des éléments du climat en R.D.C. Editions Universitaires Européennes, Saarbrücken (Allemagne), 2016; 220 p.

- Vranken, I.; Amisi,Y.M.; Munyemba, K.F.; Bamba, I.; Veroustraete, F.; Visser, M.; & Bogaert, J. The Spatial Footprint of the Non-ferrous Mining Industry in Lubumbashi. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 22-29.

- Useni, S.Y. ; Malaisse, F. ; Cabala, K.S. ; Kankumbi, F. M. ; & Bogaert, J. Le rayon de déforestation autour de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, RD Congo): synthèse. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 215-221.

- Ozer, P. Catastrophes naturelles et aménagement du territoire: de l’intérêt des images Google Earth dans les pays en développement. Geo-Eco-Trop 2014, 38, 209-220.

- Vranken, I.; Marielle, A.; Mujinya, B. B.; Munyemba, K. F.; Baert, G.; Van Ranst, E.; Visser, M.; & Bogaert, J. Termite mound identification through aerial photographic interpretation in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Methodology evaluation. Tropical Conservation Science 2014, 7, 733–746. [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J. ; Mahamane, A. Ecologie du paysage: Cibler la configuration et l’échelle spatiale. Ann. Sci. Agron. Bénin 2005, 7, 1–15.

- Liang, Y.-Q.; Li, J.-W.; Li, J.; & Valimaki, S. K. Impact of urbanization on plant diversity: A case study in built-up area of Beijing. Forestry Studies in China 2008, 10, 179–188. [CrossRef]

- Malaisse, F.; Schaijes, M.; & D'Outreligne, C. Copper-cobalt flora of Upper Katanga and Copperbelt. Field guide. Over 400 plants, 1,000 photographs and 500 drawings. Presses agronomiques de Gembloux, 2016.

- Schippers, P.; Van Groenendael, J. M.; Vleeshouwers, L. M.; & Hunt, R. Herbaceous plant strategies in disturbed habitats. Oikos 2001,95, 198-210.

- Lebrun, J. P.; & Stork, A. L. Enumération des plantes à fleurs d'Afrique tropicale et Tropical African Flowering Plants: Ecology and Distribution. Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève 1991, 2015, 1-7.

- Rija, A. A.; Said, A.; Mwamende, K. A.; Hassan, S. H.; & Madoffe, S. S. Urban sprawl and species movement may decimate natural plant diversity in an Afro-tropical city. Biodiversity Conservation 2014, 23, 963–978. [CrossRef]

- Kull, C.A.; Tassin, J.; Rambeloarisoa, G.; & Sarrailh, JM. Invasive Australian acacias on western Indian Ocean islands: a historical and ecological perspective. African Journal of Ecology 2008, 46 , p.684-89. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, P.R.; Patil, P.S.; Bairagi, V.A. Pharmacognostic, Phytochemical properties and anti-bacterial activity of Callistemon citrinus viminalis leaves and stems. International Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Science 2012, 4 , 406-408.

- Arán, D.; García-Duro, J.; Reyes, O.; Casal, M. Fire and invasive species: Modifications in the germination potential of Acacia melanoxylon, Conyza canadensis and Eucalyptus globulus. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 302, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Calviño-Cancela, M.; & Rubido-Bará, M. Invasive potential of Eucalyptus globulus: Seed dispersal, seedling recruitment and survival in habitats surrounding plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 129–137. [CrossRef]

- Dzikiti, S.; Gush, M.B.; Le Maitre, D.C.; Maherry, A.; Jovanovic, N.Z.; Ramoelo, A.; Cho, M.A. Quantifying potential water savings from clearing invasive alien Eucalyptus camaldulensis using in situ and high-resolution remote sensing data in the Berg River Catchment, Western Cape, South Africa. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 361, 69 – 80. [CrossRef]

- Meerts, P. ; Dassonville, N. ; Vanderhoeven, S. ; Chapuis-Lardy, L. ; Koutika, L.S. ; Jacquemart, A.L. Les plantes exotiques envahissantes et leurs impacts. In : Biodiversité. Etat, enjeux et perspectives. Chaire Tractebel-Environnement 2004. Ed. : De Boeck, Bruxelles, 2006 ; pp. 109-120.

- Meerts, P. An annotated checklist to the trees and shrubs of the Upper Katanga (D.R. Congo). Phytotaxa 2016, 258 , 201–50.

- Sillett, T. S.; Chandler,R. B.; Royle, J. A.; Kery, M.; & Morrison, S. A. Hierarchical distance-sampling models to estimate population size and habitat-specific abundance of an island endemic. Ecological Applications 2012, 22, 1997-2006. [CrossRef]

- Useni, S. Y.; Malaisse, F.; Yona, M. Y.; Mwamba, M. T.; & Bogaert, J. Diversity, use and management of household-located fruit trees in two rapidly developing towns in Southeastern DR Congo. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 127220. [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H. Opposite trends in response for the Shannon and Simpson indices of landscape diversity. Applied geography 2002, 22, 175-186. [CrossRef]

- GROUPE HUIT, Elaboration du plan urbain de référence de Lubumbashi. Rapport final Groupe Huit, BEAU, Ministère des ITR, RD Congo, 2009 ; 62p.

- Jim, C. Y. Green-space preservation and allocation for sustainable greening of compact cities. Cities 2004, 21, 311-320. [CrossRef]

- Bruneau J.C. ; & Pain, M. Atlas de Lubumbashi. Centre d’Etude Géographique sur l’Afrique Noire, Université Paris X, Nanterre, France, 1990 ; 201 p.

- Williams, N.S.G.; Schwartz, M.W.; Vesk, P.A.; McCarthy, M.A.; Hahs, A.K.; Clemants, S.E.; Corlett, R.T.; Duncan, R.P.; Norton, B.A.; Thompson K.; & McDonnell, M.J. A conceptual framework for predicting the effects of urban environments on floras. Journal of Ecology 2009, 97, 4-9. [CrossRef]

- Malaisse, F. Se nourrir en forêt claire africaine : Approche écologique et nutritionnelle. Gembloux, Belgique : les presses agronomiques de Gembloux, 1997.

- Trefon, T. ; & Kabuyaya, N. Les espaces périurbains en Afrique centrale. In Bogaert J. & Halleux J.M. (Eds). Territoires périurbains : développement, enjeux et perspectives dans les pays du sud. Les presses agronomiques de Gembloux, Gembloux, Belgique, 2015; pp 33-42.

- Janzen, D. H. Herbivores and the number of tree species in tropical forests. The American Naturalist 1970, 104, 501-528. [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.H. On the role of natural enemies in preventing competitive exclusion in some marine animals and in rain forest trees. In: Den Boer P.J. & Gradwell G. (Eds). Dynamics of populations. PUDOC, 1971; 298-312.

- Azihou, A. F.; Kakaï, R. G.; Bellefontaine, R.; & Sinsin, B. Distribution of tree species along a gallery forest–savanna gradient: patterns, overlaps and ecological thresholds. Journal of Tropical Ecology 2013, 29, 25-37.

- Shackleton, S.; Chinyimba,A.; Hebinck, P.; Shackleton, C. M.; & Kaoma, H. Multiple benefits and values of trees in urban landscapes in two towns in northern South Africa. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 136, 76–86. [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T.; & M. Godron, Landscape ecology. John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1986; 640p.

- Toyi, M.S. ; Barima, Y.S.S. ; Mama, A. ; André, M. ; Bastin, J-F.; De Cannière, C.; Sinsin, B.; & Bogaert, J. Tree plantation will not compensate natural woody vegetation cover loss in the Atlantic department of southern Benin. Tropicultura, 2013, 31, 62-70. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/160471.

- Elliott, K. J.; Boring, L. R.; & Swank, W. T. Changes in vegetation structure and diversity after grass-to-forest succession in a southern Appalachian watershed. The American Midland Naturalist 1998, 140, 219-232. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, N.B.; Faeth, S.H.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Redman, C.L.; Wu, J.; Bai, X.; & Briggs, J.M. Global change and the ecology of cities. Sciences 2008, 319, 756-760. [CrossRef]

- Chidumayo, E. N. Forest degradation and recovery in a miombo woodland landscape in Zambia: 22 years of observations on permanent sample plots. Forest Ecology and Management 2013, 291, 154-161. [CrossRef]

- Syampungani, S.; Tigabu, M.; Matakala, N.; Handavu, F.; & Oden, P. C. Coppicing ability of dry miombo woodland species harvested for traditional charcoal production in Zambia: a win–win strategy for sustaining rural livelihoods and recovering a woodland ecosystem. Journal of Forestry Research 2017, 28, 549-556. [CrossRef]

- Hardarson, G.; Danso, S.K.A. Methods for measuring biological nitrogen fixation in grain legumes. In: Bliss, F.A., Hardarson, G. (eds) Enhancement of Biological Nitrogen Fixation of Common Bean in Latin America. Developments in Plant and Soil Sciences 1993, 52. [CrossRef]

- Akondé, T. P. Potential of alley cropping with" Leucaena leucocephala"(Lam.) de Wit and" Cajanus cajan (L.) millsp. for maize (Zea mays L.) and cassava, Manihot esculenta Crantz) production on acrisol in Benin Republic (West Africa) (Doctoral dissertation, Universität Hohenheim), 1995.

- Wuenschel, A. Impacts écologiques potentiels à long-terme des plantations d’Acacias non-natifs dans la région de Kinshasa, en RDC , 2019 ; 37p.

- Kikvidze, Z.; & Callaway, R. M. Ecological facilitation may drive major evolutionary transitions. BioScience 2009, 59, 399-404.

- Kasongo, R.K.; Van Ranst, E.; Verdoodt, A.; Kanyankogote, P.; & Baert, G. Impact of Acacia auriculiformis on the chemical fertility of sandy soils on the Bate ́ke ́ plateau, D.R Congo. Soil Use and Management 2009, 25, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Nsombo, B. M. ; Lumbuenamo, R. S. ; Lejoly, J. ; Aloni, J. K. ; & Mafuka, P. M. M. Caractéristiques des sols sous savane et sous forêt naturelle sur le plateau des Batéké en République démocratique du Congo. Tropicultura 2016, 34, 87-97.

- Kooke, G.X. ; Ali, R.K.F.M. ; Djossou, J.M. et al. Estimation du stock de carbone organique dans les plantations de Acacia auriculiformis A. Cunn. ex Benth. des forêts classées de Pahou. Int J Bio Chem Sci 2019, 13, 277-293. [CrossRef]

- Gnahoua G. M. ; & Louppe, D. Acacia auriculiformis, 2003.

- Kolawolé, R. F. M. A. Phytodiversité dans les plantations de Acacia auriculiformis de la forêt classée de Ouèdo au Sud du Bénin, Asian Journal of Science and Technology 2019, 10, 10056-10066.

- Laurance, W. F.; Nascimento, H. E.; Laurance, S. G.; Andrade, A.; Ewers, R. M.; Harms, K. E. ... & Ribeiro, J. E. Habitat fragmentation, variable edge effects, and the landscape-divergence hypothesis. PLoS one 2007, 2, e1017.

- Lubbe, C. S.; Siebert, S. J.; & Cilliers, S. S. Political legacy of South Africa affects the plant diversity patterns of urban domestic gardens along a socio-economic gradient. Scientific Research and Essays 2010, 5, 2900-2910.

- Zmyslony, J.; & Gagnon, D. Residential management of urban front-yard landscape: a random process? Landscape and Urban Planning 1998, 40, 295-307. [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, M. ; & Malaisse, F. Lubumbashi, un écosystème urbain tropical. Centre International de Sémiologie, Université Nationale du Zaïre, 1978 ; 166p.

- Lowry, J. B.; Prinsen, J. H.; & Burrows, D. M. Albizia lebbeck-a promising forage tree for semiarid regions. Forage tree legumes in tropical agriculture, 1994; 75-83.

- Godefroid, S. Temporel analysis of the Brussels flora as indicator for changing environmental quality. Landscape and Urban Planning 2001, 52 , 203-224. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, F. J.; Sadras, V. O.; & Fereres, E. Plant density and competition. In Principles of Agronomy for Sustainable Agriculture Springer, Cham, 2016; 159-168. [CrossRef]

- Cordonnier, T. Perturbations, diversité et permanence des structures dans les écosystèmes forestiers. Thèse de doctorat, ENGREF, France, 2004 ; 259 p.

- Olofsson, J.; de Mazancourt, C.; & Crawley, M.J. Spatial heterogeneity and plant species richness at different spatial scales under rabbit grazing. Oecologia 2008, 156, 825-834. [CrossRef]

- White, P. S.; & Jentsch, A. The search for generality in studies of disturbance and ecosystem dynamics. Progress in botany: Genetics physiology systematics ecology, 2001; 399-450.

- Cristofoli, S. & Mahy, G. Restauration écologique : contexte, contraintes et indicateurs de suivi. Biotechnology, Agronomy, Society and Environment 2010, 14, 203-211. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/21031.

- Bullock, J. M.; Aronson, J.; Newton, A. C.; Pywell, R. F.; Rey-Benayas, J. M. Restoration of ecosystem services and biodiversity. Conflicts and opportunities. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2011, 26 , 541-549. [CrossRef]

- King, E. G.; Hobbs, R. J. Identifying linkages among conceptual models of ecosystem degradation and restoration: towards an integrative framework. Restoration Ecology 2006, 14 , 369-378. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Power, M. E.; Comín, F. A.; Yockteng, R. Structural and functional loss in restored wetland ecosystems. Plos Biology 2012, 10 , 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Havyarimana, F.; Bamba, I.; Barima, Y.S.S.; Masharabu, T.; Nduwarugira, D.; Bigendako, M-J.; Mama, A. ; Bangirimana, F. ; De Cannière, C. ; & Bogaert, J. La contribution des camps des déplacés à la dynamique paysagère au Sud et au Sud-est du Burundi. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 243-257.

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation. Bioscience, 2002, 52, 883-890. [CrossRef]

- Useni, S.Y.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Maréchal, J.; Ilunga, W.I.E.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, K.F. Changes in the Spatial Pattern and Ecological Functionalities of Green Spaces in Lubumbashi (the Democratic Republic of Congo) in Relation with the Degree of Urbanization. Tropical Conservation Science 2018, 11, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, R. T.; Shackleton, C. M.; & Kull, C. A. The role of invasive alien species in shaping local livelihoods and human well-being: A review. Journal of environmental management 2019, 229, 145-157. [CrossRef]

- Amandine, S. Impact de l’Acacia auriculiformis sur les propriétés des sols sableux du plateau Batéké, République Démocratique du Congo. Master thesis : Université Catholique de Louvain, 2011 ; 98 p.

- Kaumbu, J.M.K.; Mpundu, M.M.M.; Kasongo, E.L.M.; Ngoy Shutcha, M.; Kalambulwa, A.N.; Khasa, D. Early Selection of Tree Species for Regeneration in Degraded Woodland of Southeastern Congo Basin. Forests 2021, 12 () 1–16.

| Attached green space | Park | Street trees | ||||

| PN | CA (ha) | PN | CA (ha) | PN | CA (ha) | |

| 2006 | ||||||

| PZ | 1 | 1.60 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| UZ | 7 | 12.33 | 1 | 0.14 | 3 | 1.21 |

| 2014 | ||||||

| PZ | 2 | 4.18 | 1 | 4.36 | 0 | 0.00 |

| UZ | 8 | 18.36 | 1 | 0.33 | 5 | 2.15 |

| 2021 | ||||||

| PZ | 1 | 0.65 | 1 | 5.27 | 0 | 0.00 |

| UZ | 9 | 18.21 | 1 | 0.14 | 5 | 3.62 |

| 2006-2014 | 2014-2021 | |||||

| RC in PZ | 433.75 | -30.68 | ||||

| RC in UZ | 52.33 | 113 | ||||

| Indices | UZ | PZ |

|---|---|---|

| Species richness (n=39) | 29 | 20 |

| Genera (n=29) | 20 | 16 |

| Family (15) | 11 | 9 |

| Simpson_1-D | 0.76 | 0.68 |

| Shannon_H | 2.34 | 1.63 |

| Proportion of adult (%) | Proportion of seedling (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| UZ (n=207) | 94.2 | 5.8 |

| PU (n=150) | 89.3 | 10.7 |

| Average height (m) | Average diameter (cm) | |

|---|---|---|

| UZ (n=104) | 10.87±4.09 | 28.02±14.8 |

| PZ (n=61) | 11.03±10.6 | 30.4±15.7 |

| T | 0.11 | 0.96 |

| p-value | ns | ns |

| Family | Species | RA UZ (n=223) | RA PZ (n=134) | RF UZ (n=4) | RF PZ (n=2) | Origin status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | 3.1 | 1.5 | 25.0 | 50.0 | Ex |

| Apocynaceae | *Diplorhynchus condylocarpon (Muell. Arg.) Pichon | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Arecaceae | Elaeis guineensis Jacq. | 1.3 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | In |

| Ebenaceae | *Diospyros discolor Willd. | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | +Acacia auriculiformis A. Cunn. ex Benth. | 46.6 | 45.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | +Acacia heterophylla Willd. | 4.5 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | +Acacia mangium Willd. | 2.7 | 3.0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | +Acacia melanoxylon R.Br. | 2.2 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | *Baphia bequaertii De Wild. | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | Bauhinia variegata L. | 1.3 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | *Brachystegia boehmii Taub. | 3.1 | 0.7 | 25.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | *Brachystegia longifolia Benth. | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | *Brachystegia spiciformis Benth. | 1.3 | 0.7 | 25.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | Ceratonia siliqua L. | 2.7 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | Delonix regia (Bojer) Rafin | 1.3 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | *Erythrophleum africanum (Welw. ex Benth.) Harms | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | *Isoberlinia angolensis (Benth.) Hoyle & Brenan | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | *Julbernardia paniculata (Benth.) Troupin. | 1.8 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | *Pterocarpus angolensis D.C | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Fabaceae | Senna siamea Lam. | 0.4 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Fabaceae | Tipuana tipu (Benth.) Kuntze | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | Ex |

| Kirkiaceae | *Kirkia acuminata Oliv. | 0.9 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | In |

| Lamiaceae | *Vitex madiensis Oliv. | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | 0.9 | 0.7 | 25.0 | 50.0 | Ex |

| Meliaceae | +Melia azedarach L. | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 50.0 | Ex |

| Mimosaceae | *Albizia adianthifolia (Schum.) W. F. Wight | 1.3 | 6.7 | 25.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Mimosaceae | Albizia brevifolia Schinz. | 0.4 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Mimosaceae | +Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth. | 2.7 | 30.6 | 50.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Mimosaceae | +Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) De Wit. | 7.2 | 2.2 | 50.0 | 50.0 | Ex |

| Moraceae | *Ficus benjamina L. | 0.4 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | In |

| Moraceae | *Ficus sp | 0.9 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | In |

| Moraceae | *Ficus sycomorus L. | 1.3 | 0.7 | 25.0 | 50.0 | In |

| Myrtaceae | +Callistemon viminalis (Sol. ex Gaertn.) G.Don | 0.9 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Myrtaceae | +Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | 2.2 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Myrtaceae | +Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | 0.9 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Phyllanthaceae | *Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia Pax. | 3.1 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | In |

| Pinaceae | Abies alba Mill. | 2.2 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Pinaceae | Pinus pinea L. | 0.4 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | Ex |

| Rhamnaceae | *Ziziphus mucronata Willd. | 1.3 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 | In |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).