Submitted:

21 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

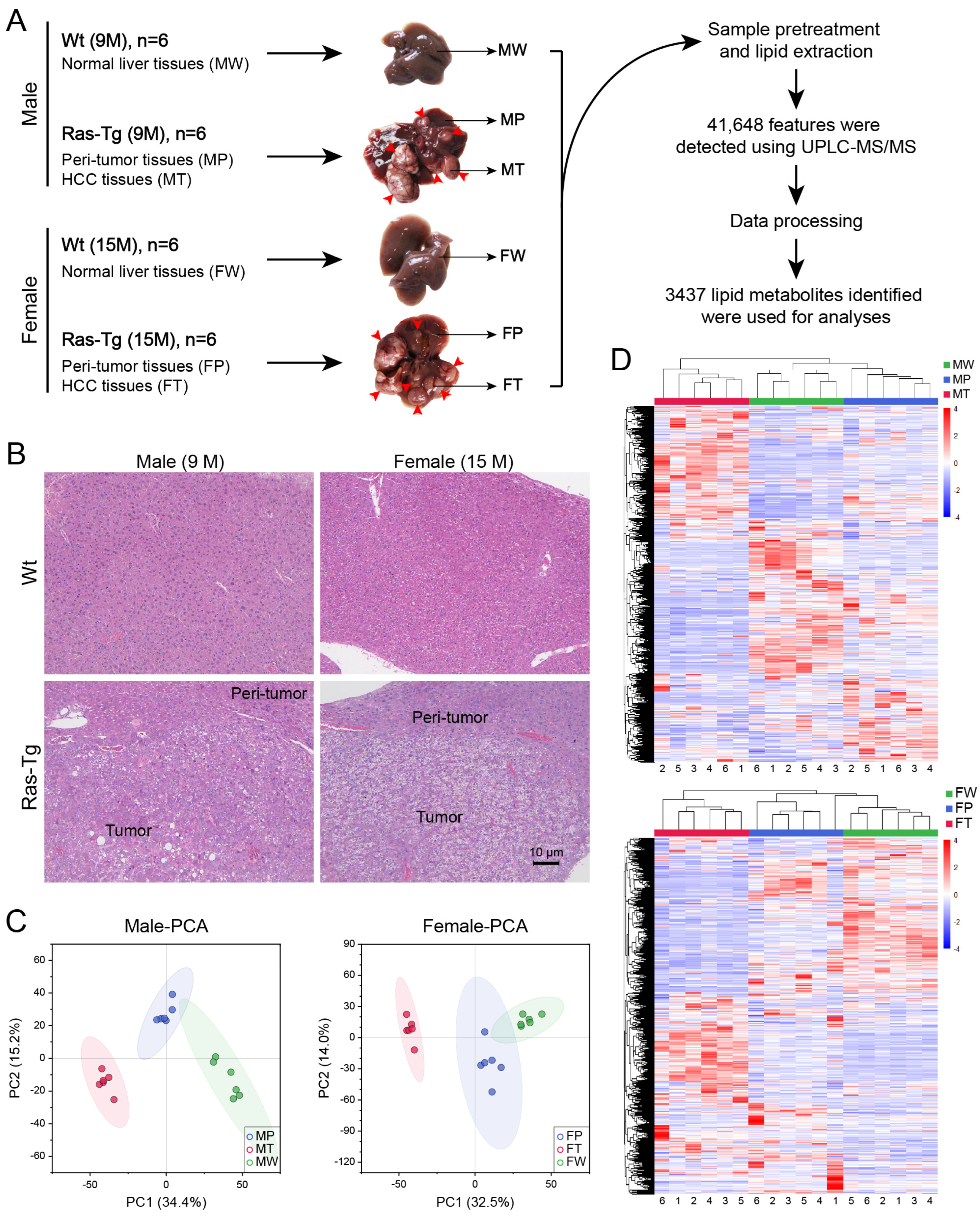

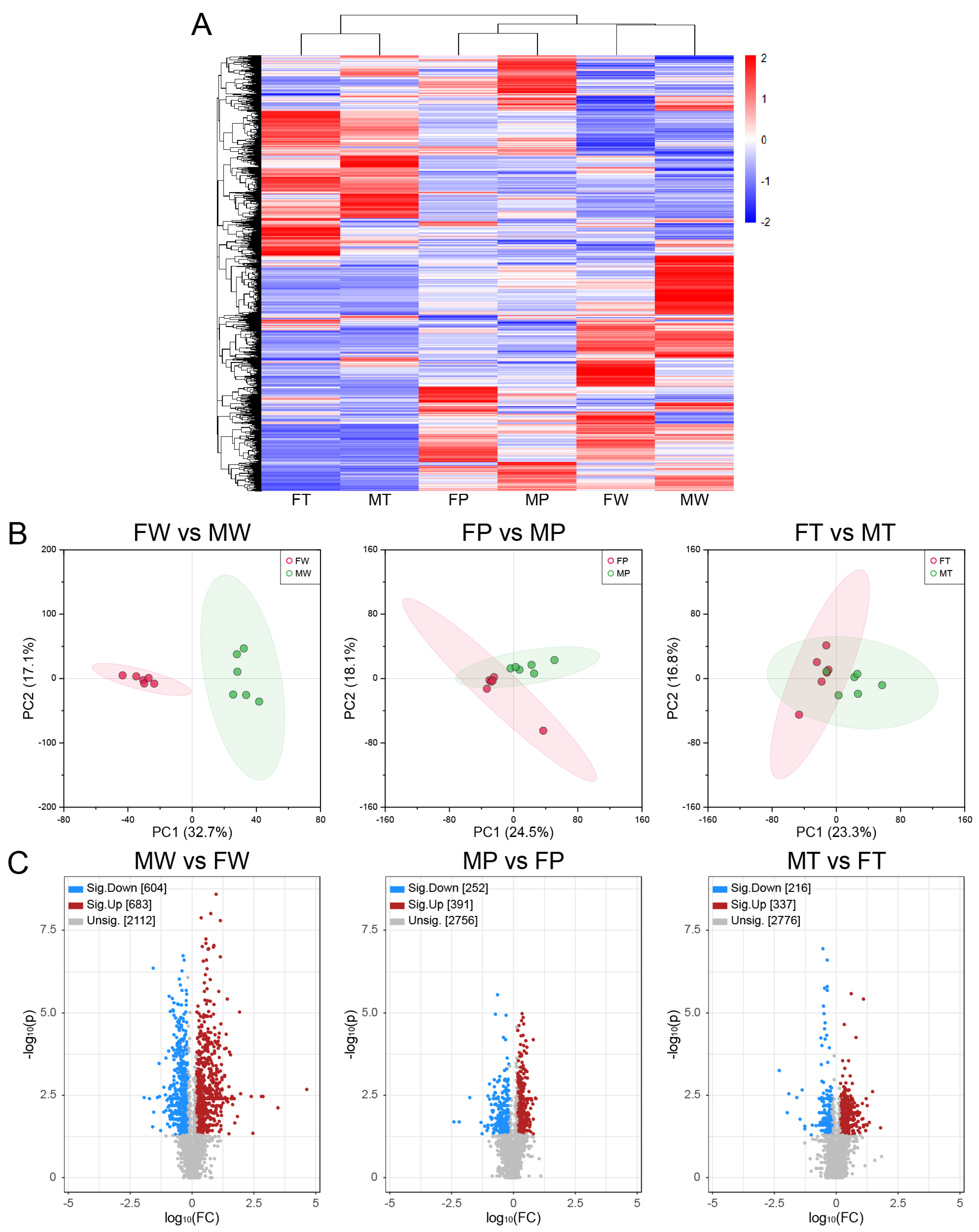

2.1. Workflow and validation of the quality of lipidomics data

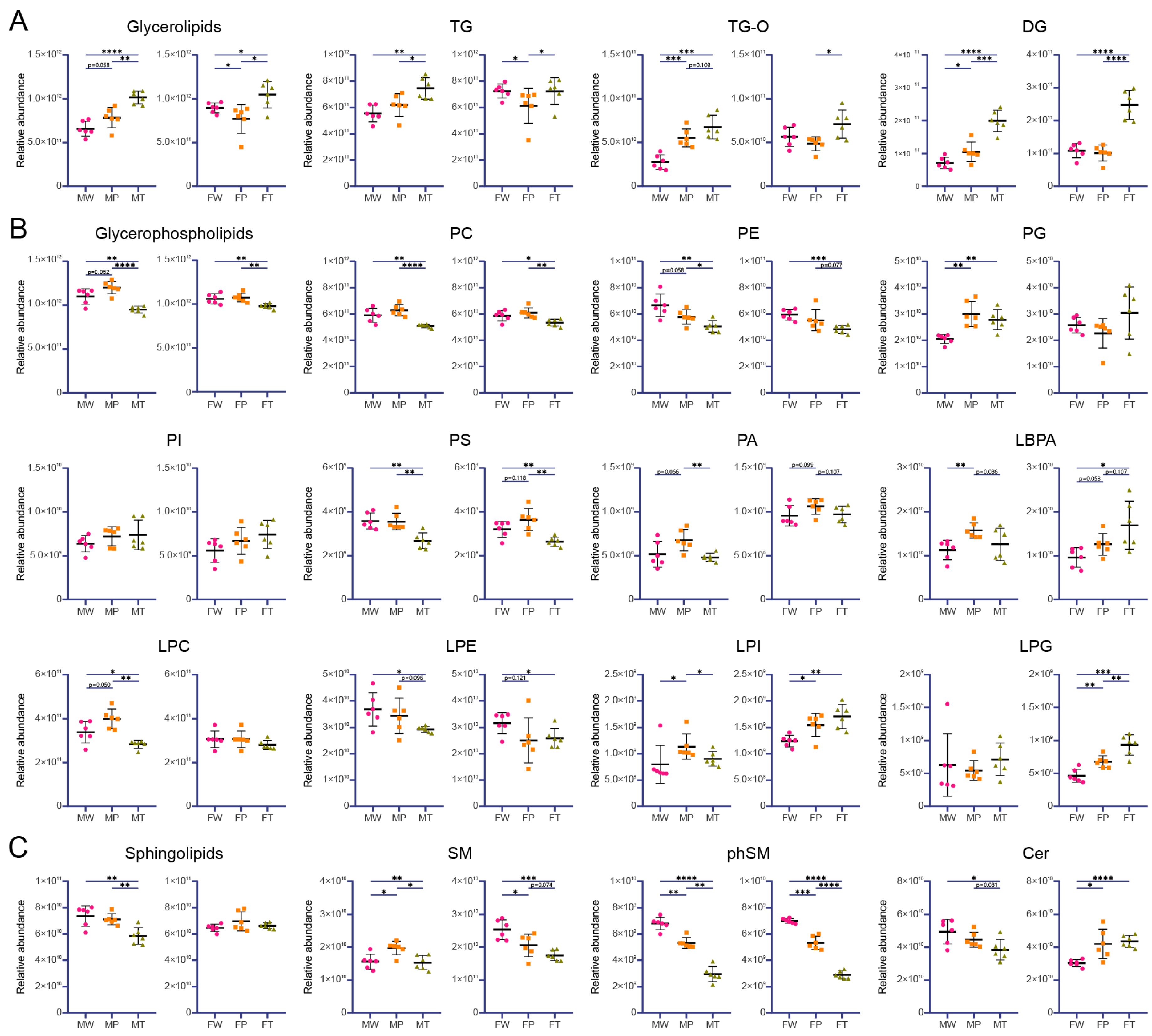

2.2. Lipid composition analysis

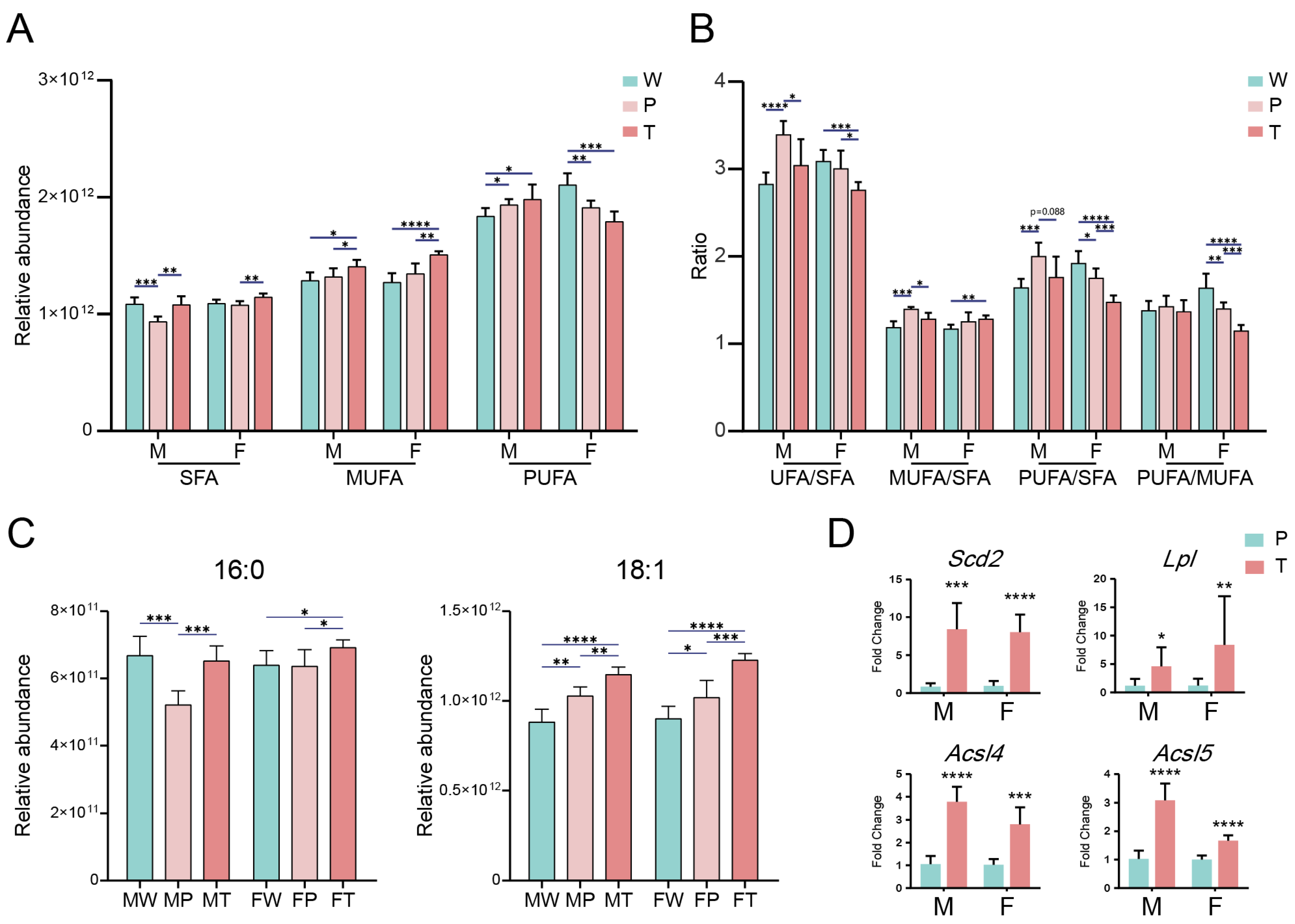

2.3. Accumulation of saturated FA (SFA) and monounsaturated FA (MUFA) in hepatic carcinogenesis

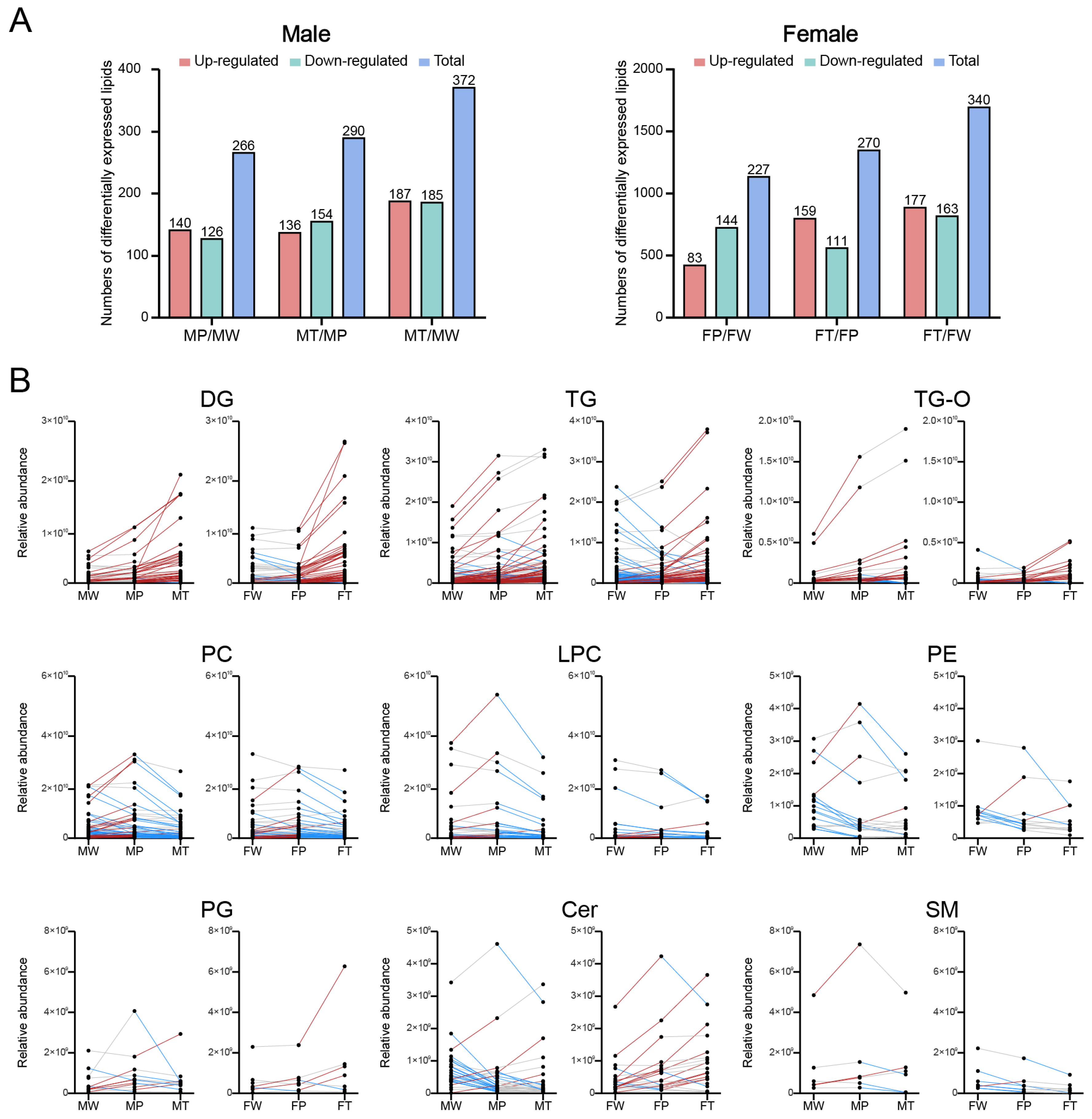

2.4. Identification of deferentially expressed lipids (DELs)

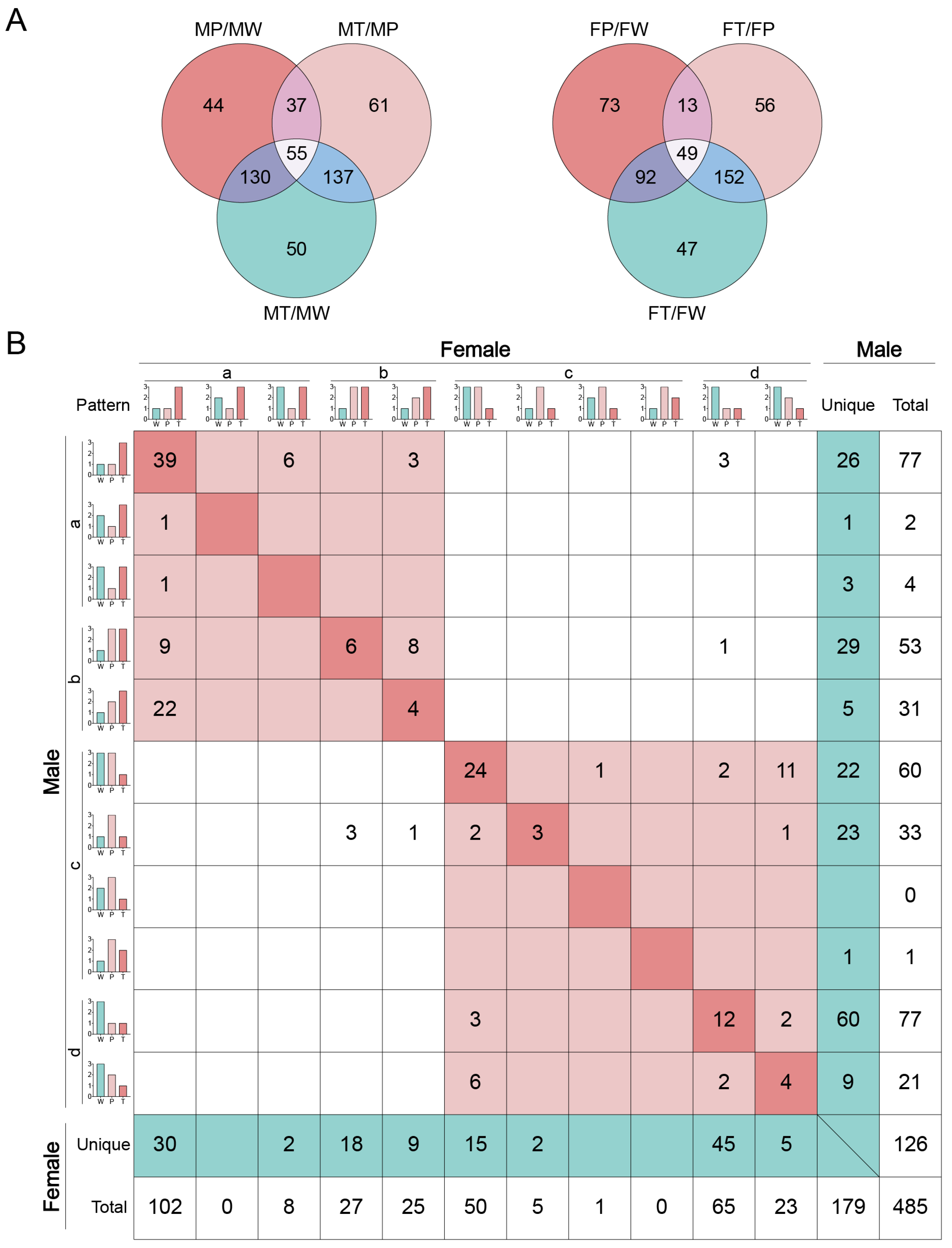

2.5. Common and unique DELs involved in sex-dependent hepatocarcinogenesis

” model (refer to Table 1 for a description of this and the following symbols), indicating their weak responses to the Ras oncogene. The remaining DELs belong to “

” model (refer to Table 1 for a description of this and the following symbols), indicating their weak responses to the Ras oncogene. The remaining DELs belong to “ ” model, indicating they responded negatively to the Ras oncogene and, therefore, may be suppressed by the cancer prevention system in precancerous hepatocytes. In category (c), DELs play a negatively role in HCC. Among them, the DELs belonging to “

” model, indicating they responded negatively to the Ras oncogene and, therefore, may be suppressed by the cancer prevention system in precancerous hepatocytes. In category (c), DELs play a negatively role in HCC. Among them, the DELs belonging to “ ” model had a weak response to Ras oncogene, and the DELs belonging to “

” model had a weak response to Ras oncogene, and the DELs belonging to “ ” model responded positively to the Ras oncogenes expression in hepatocytes and, thus, may be activated by the cancer prevention system in precancerous hepatocytes. Categories (b) and (d) indicate that DELs respond positively or negatively to Ras oncogene expression in hepatocytes and hepatoma cells, respectively.

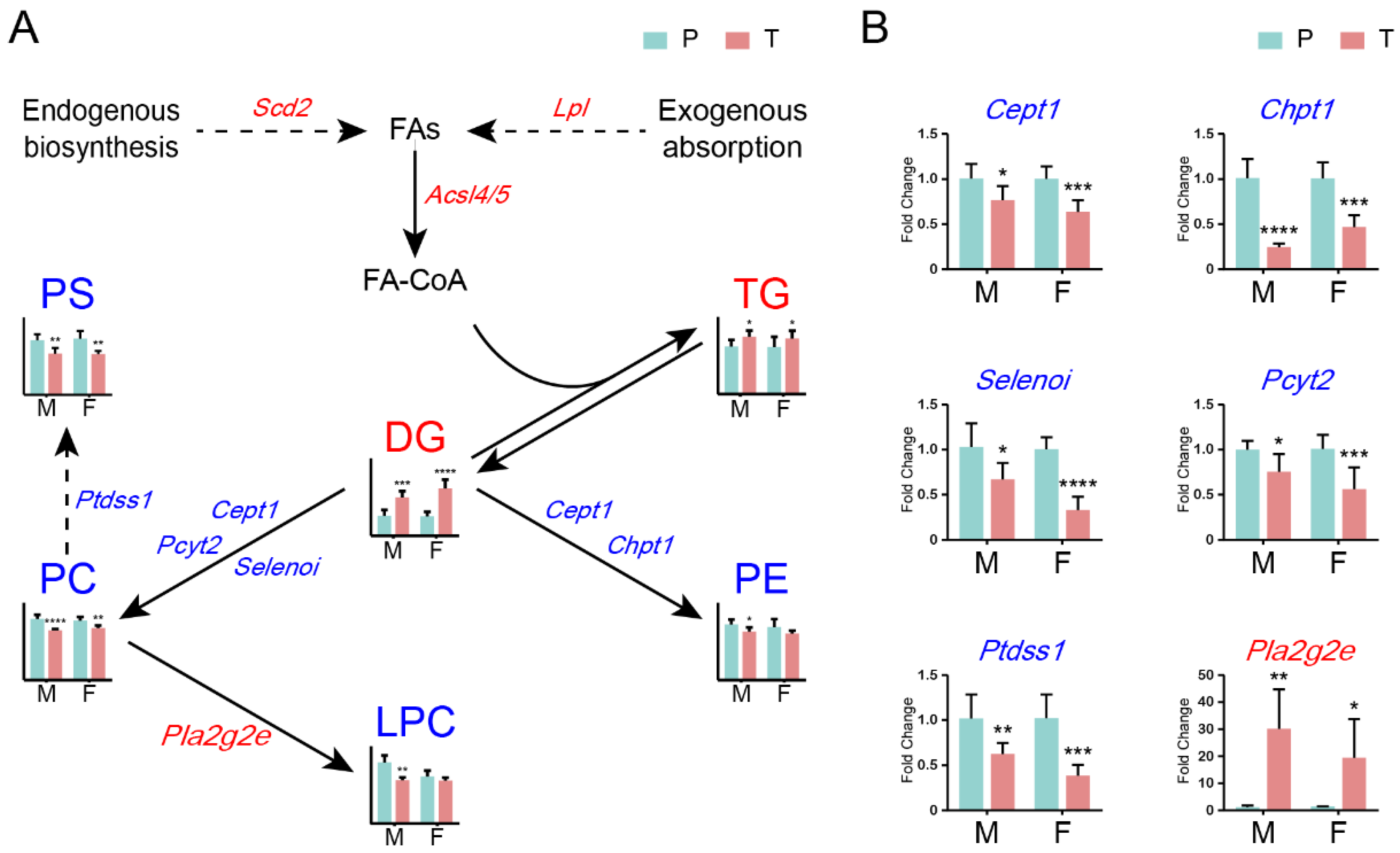

” model responded positively to the Ras oncogenes expression in hepatocytes and, thus, may be activated by the cancer prevention system in precancerous hepatocytes. Categories (b) and (d) indicate that DELs respond positively or negatively to Ras oncogene expression in hepatocytes and hepatoma cells, respectively.2.6. Roles of glycerolipid and glycerophospholipid metabolisms in HCC in both sexes

2.7. Converging trend of lipid compositions during hepatocarcinogenesis between sexes

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Animals, sampling, and histopathological examination

5.2. Experimental design and DELs screening

5.3. Nontargeted lipidomics analysis based on UPLC-MS/MS

5.4. Data Processing

5.5. Real time quantitative PCR

5.6. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- El-Serag, H.B.; Rudolph, K.L. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2557–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodama, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Hyogo, H.; Nakajima, T.; Ono, M.; Seike, M.; Takahashi, H.; Nozaki, Y.; Kawanaka, M.; Tanaka, S.; et al. Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients without advanced fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 34, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangineto, M.; Villani, R.; Cavallone, F.; Romano, A.; Loizzi, D.; Serviddio, G. Lipid Metabolism in Development and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhu, A.; Roessler, S.; Zhao, X.; Yu, Z.; Forgues, M.; Ji, J.; Karoly, E.; Qin, L.X.; Ye, Q.H.; Jia, H.L.; et al. Integrated metabolite and gene expression profiles identify lipid biomarkers associated with progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and patient outcomes. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Du, G. Dysregulated lipid metabolism in cancer. World J Biol Chem 2012, 3, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.; Liu, R.; Meng, Y.; Xing, D.; Xu, D.; Lu, Z. Lipid metabolism and cancer. J Exp Med 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenk, M.R. Lipidomics: New tools and applications. Cell 2010, 143, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedaly, R.; Angulo, P.; Hundley, J.; Daily, M.F.; Chen, C.; Evers, B.M. PKI-587 and sorafenib targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Ras/Raf/MAPK pathways synergistically inhibit HCC cell proliferation. J Surg Res 2012, 176, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvisi, D.F.; Ladu, S.; Gorden, A.; Farina, M.; Conner, E.A.; Lee, J.S.; Factor, V.M.; Thorgeirsson, S.S. Ubiquitous activation of Ras and Jak/Stat pathways in human HCC. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, C.Y.; Wei, L.X.; Wang, Y.L.; Dai, G.H. Expression and prognostic role of pan-Ras, Raf-1, pMEK1 and pERK1/2 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2011, 37, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolacci, C.; Andreani, C.; El-Gammal, Y.; Scaglioni, P.P. Lipid Metabolism Regulates Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis in RAS-Driven Cancers: A Perspective on Cancer Progression and Therapy. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8, 706650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.G.; Moon, H.B.; Lee, M.R.; Hwang, C.Y.; Kwon, K.S.; Yu, S.L.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.K.; et al. Gender-dependent hepatic alterations in H-ras12V transgenic mice. J Hepatol 2005, 43, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.G.; Moon, H.B.; Chae, J.I.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, Y.E.; Yu, D.Y.; Lee, D.S. Steatosis induced by the accumulation of apolipoprotein A-I and elevated ROS levels in H-ras12V transgenic mice contributes to hepatic lesions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011, 409, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, Z.; Fan, T.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Dong, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; et al. Differential Proteomic Analysis of Gender-dependent Hepatic Tumorigenesis in Hras12V Transgenic Mice. Mol Cell Proteomics 2017, 16, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.F.; Zheng, Y. Applications of Multivariate Statistical and Data Mining Analyses to the Search for Biomarkers of Sensorineural Hearing Loss, Tinnitus, and Vestibular Dysfunction. Front Neurol 2021, 12, 627294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Rong, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, N.; Pu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Lei, C.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; et al. Proteomic analysis revealed common, unique and systemic signatures in gender-dependent hepatocarcinogenesis. Biol Sex Differ 2020, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentki, M.; Madiraju, S.R. Glycerolipid metabolism and signaling in health and disease. Endocr Rev 2008, 29, 647–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, C.; Li, N.; Zou, L.; Chia, S.E.; Chen, S.; Yu, K.; Ling, Q.; Cheng, Q.; et al. Comparison of hepatic and serum lipid signatures in hepatocellular carcinoma patients leads to the discovery of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 5032–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberl, E.M.; Pohl, R.; Rein-Fischboeck, L.; Horing, M.; Krautbauer, S.; Liebisch, G.; Buechler, C. Accumulation of cholesterol, triglycerides and ceramides in hepatocellular carcinomas of diethylnitrosamine injected mice. Lipids Health Dis 2021, 20, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.P.; Hannun, Y.A. Protein kinase C and phospholipase D: Intimate interactions in intracellular signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005, 62, 1448–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlasa, W.; Zendran, I.; Zalesinska, A.; Tarek, M.; Kulbacka, J. Lipid composition of the cancer cell membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2020, 52, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Mei, H.; Mao, J.; Zhou, X. Distribution and clinical relevance of phospholipids in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2020, 14, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, H.; Xiao, M.; Zarkovic, K.; Zhu, M.; Sa, R.; Lu, J.; Tao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xia, L.; Cheng, S.; et al. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis through modulation of cardiolipin oxidation in hepatocellular carcinoma: A novel link between oxidative stress and cancer. Free Radic Biol Med 2017, 102, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, I.T.; Elfert, A.; Helal, M.; Salama, I.; El-Said, H.; Fiehn, O. Remodeling Lipids in the Transition from Chronic Liver Disease to Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Yin, P.; Ye, G.; Gao, P.; Lu, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, G. Metabolic characterization of hepatocellular carcinoma using nontargeted tissue metabolomics. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 4992–5002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri, Y.; Colombi, M.; Dazert, E.; Hindupur, S.K.; Roszik, J.; Moes, S.; Jenoe, P.; Heim, M.H.; Riezman, I.; Riezman, H.; et al. mTORC2 Promotes Tumorigenesis via Lipid Synthesis. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechler, C.; Aslanidis, C. Role of lipids in pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2020, 1865, 158658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.K.; Jacobs, R.L.; Watts, J.L.; Rottiers, V.; Jiang, K.; Finnegan, D.M.; Shioda, T.; Hansen, M.; Yang, F.; Niebergall, L.J.; et al. A conserved SREBP-1/phosphatidylcholine feedback circuit regulates lipogenesis in metazoans. Cell 2011, 147, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, E.J.; Wankell, M.; Palamuthusingam, P.; McFarlane, C.; Hebbard, L. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koundouros, N.; Poulogiannis, G. Reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer 2020, 122, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, E.D., 3rd; Kimbrough, E.O.; Vemireddy, L.P.; Surapaneni, P.K.; Copland, J.A., 3rd; Mody, K. Aberrant lipid metabolism as a therapeutic target in liver cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2019, 23, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.L.W.; Israeli, E.; Ericksen, R.E.; Chow, P.K.H.; Han, W. The altered lipidome of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvisi, D.F.; Wang, C.; Ho, C.; Ladu, S.; Lee, S.A.; Mattu, S.; Destefanis, G.; Delogu, S.; Zimmermann, A.; Ericsson, J.; et al. Increased lipogenesis, induced by AKT-mTORC1-RPS6 signaling, promotes development of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, J.; Fei, F.; Dong, Z.; Ke, A.W.; He, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Ji, M.B.; et al. Canonical Wnt Signaling Remodels Lipid Metabolism in Zebrafish Hepatocytes following Ras Oncogenic Insult. Cancer Res 2018, 78, 5548–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igal, R.A. Roles of StearoylCoA Desaturase-1 in the Regulation of Cancer Cell Growth, Survival and Tumorigenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2011, 3, 2462–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffitts, J.; Tesiram, Y.; Reid, G.E.; Saunders, D.; Floyd, R.A.; Towner, R.A. In vivo MRS assessment of altered fatty acyl unsaturation in liver tumor formation of a TGF alpha/c-myc transgenic mouse model. J Lipid Res 2009, 50, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, M.; Dobrzyn, A.; Elias, P.M.; Ntambi, J.M. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-2 gene expression is required for lipid synthesis during early skin and liver development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 12501–12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, C.; Calvisi, D.F.; Evert, M.; Pilo, M.G.; Jiang, L.; Yuneva, M.; Chen, X. SCD1 Expression is dispensable for hepatocarcinogenesis induced by AKT and Ras oncogenes in mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yamamoto, M.; Fujii, K.; Nagahama, Y.; Ooshio, T.; Xin, B.; Okada, Y.; Furukawa, H.; Nishikawa, Y. Differential reactivation of fetal/neonatal genes in mouse liver tumors induced in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic conditions. Cancer Sci 2015, 106, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Jeong, D.W.; Park, J.W.; Lee, K.W.; Fukuda, J.; Chun, Y.S. Fatty-acid-induced FABP5/HIF-1 reprograms lipid metabolism and enhances the proliferation of liver cancer cells. Commun Biol 2020, 3, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulucci, G.; Cohen, O.; Daniel, B.; Sansone, A.; Petropoulou, P.I.; Filou, S.; Spyridonidis, A.; Pani, G.; De Spirito, M.; Chatgilialoglu, C.; et al. Fatty acid-related modulations of membrane fluidity in cells: Detection and implications. Free Radic Res 2016, 50, S40–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, Z.; Chiarugi, D.; Charidemou, E.; Leslie, J.; Scott, E.; Pellegrinet, L.; Allison, M.; Mocciaro, G.; Anstee, Q.M.; Evan, G.I.; et al. Lipid Remodeling in Hepatocyte Proliferation and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2021, 73, 1028–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maria, N.; Manno, M.; Villa, E. Sex hormones and liver cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2002, 193, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.J.; Wu, C.C.; Huang, H.P.; Liu, J.Y.; Lin, C.S.; Chang, Y.Z.; Lin, J.A.; Lin, J.G.; Chen, L.M.; Lee, S.D.; et al. Apoptotic and anti-proliferative effects of 17beta-estradiol and 17beta-estradiol-like compounds in the Hep3B cell line. Mol Cell Biochem 2006, 290, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasue, N.; Yu, L.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kohno, H.; Tachibana, M.; Kubota, H. Inhibition of growth and induction of TGF-beta 1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma with androgen receptor by cyproterone acetate in male nude mice. J Hepatol 1996, 25, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbare, J.C.; Bouche, O.; Bonnetain, F.; Raoul, J.L.; Rougier, P.; Abergel, A.; Boige, V.; Denis, B.; Blanchi, A.; Pariente, A.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of tamoxifen in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23, 4338–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Malladi, S.; Beck, A.H. Systematic Analysis of Sex-Linked Molecular Alterations and Therapies in Cancer. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, B.T.; Bianco-Miotto, T.; Buckberry, S.; Breen, J.; Clifton, V.; Shoubridge, C.; Roberts, C.T. Large Scale Gene Expression Meta-Analysis Reveals Tissue-Specific, Sex-Biased Gene Expression in Humans. Front Genet 2016, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakiri, L.; Wagner, E.F. Mouse models for liver cancer. Mol Oncol 2013, 7, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, C.H.; Ward, J.M. A morphologic classification of proliferative and neoplastic hepatic lesions in mice. J Environ Pathol Toxicol 1979, 3, 329–351. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. , Zeng, Z., Chen, A., Lu, X., Zhao, C., Hu, C., Zhou, L., Liu, X., Wang, X., Hou, X., Ye, Y., Xu, G. Comprehensive Strategy to Construct In-House Database for Accurate and Batch Identification of Small Molecular Metabolites. Anal Chem. 2018, 90, 7635–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Models | Description | Regulated Lipids | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

|

First reduced in P and then elevated in T | Total glycerolipid, TG | |

|

First elevated in P and then reduced in T | Total glycerophospholipid, PA, LBPA, LPC, LPI, SM | PS, PA |

|

Continuous reduced in P and T | PE, phSM | SM, phSM |

|

Continuous elevated in P and T | Total glycerolipid, TG-O, DG | LBPA, LPG |

|

Unchanged between W and P but reduced in T | Total sphingolipid, PC, PS, LPE, Cer | Total glycerophospholipid, PC, PE |

|

Unchanged between W and P but elevated in T | TG | TG-O, DG |

|

First reduced in P and then remained in T | LPE | |

|

First elevated in P and then remained in T | PG | LPI, Cer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).