Submitted:

18 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. The Theory of Planned Behaviour

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Attitude and Environmentally Responsible Behavioral Intention

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Size

3.2. Research Instruments

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Results

3.5.1. Data Description

Means and Standard Deviation

Measurement Model Test: Reliability and Validity

| Construct | Item | Factor loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | ATT1 | 0.755 | 0.725 | 0.744 | 0.819 | 0.537 |

| ATT2 | 0.777 | |||||

| ATT3 | 0.652 | |||||

| ATT4 | 0.604 | |||||

| ATT5 | 0.648 | |||||

| Subjective norm | SN1 | 0.688 | 0.720 | 0.722 | 0.826 | 0.543 |

| SN2 | 0.753 | |||||

| SN3 | 0.714 | |||||

| SN4 | 0.790 | |||||

| Perceived behavioral control | BC1 | 0.772 | 0.792 | 0.815 | 0.855 | 0.543 |

| BC2 | 0.716 | |||||

| BC3 | 0.640 | |||||

| BC4 | 0.729 | |||||

| BC5 | 0.816 | |||||

| Awareness of consequences | AC1 | 0.815 | 0.868 | 0.868 | 0.904 | 0.654 |

| AC2 | 0.800 | |||||

| AC3 | 0.818 | |||||

| AC4 | 0.779 | |||||

| AC5 | 0.832 | |||||

| Behavioral intention | BI1 | 0.828 | 0.855 | 0.855 | 0.902 | 0.698 |

| BI2 | 0.864 | |||||

| BI3 | 0.868 | |||||

| BI4 | 0.779 |

Discriminant Validity

| Attitude | Awareness of consequences | Behavioral control | Behavioral intention | Subjective norm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.691 | ||||

| Awareness of consequences | 0.498 | 0.709 | |||

| Behavioral control | 0.574 | 0.511 | 0.737 | ||

| Behavioral intention | 0.483 | 0.627 | 0.570 | 0.736 | |

| Subjective norm | 0.546 | 0.392 | 0.686 | 0.498 | 0.737 |

| Attitude | Awareness of consequences | Behavioral control | Behavioral intention | Subjective norm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | |||||

| Awareness of consequences | 0.630 | ||||

| Behavioral control | 0.761 | 0.603 | |||

| Behavioral intention | 0.601 | 0.726 | 0.671 | ||

| Subjective norm | 0.774 | 0.488 | 0.912 | 0.625 |

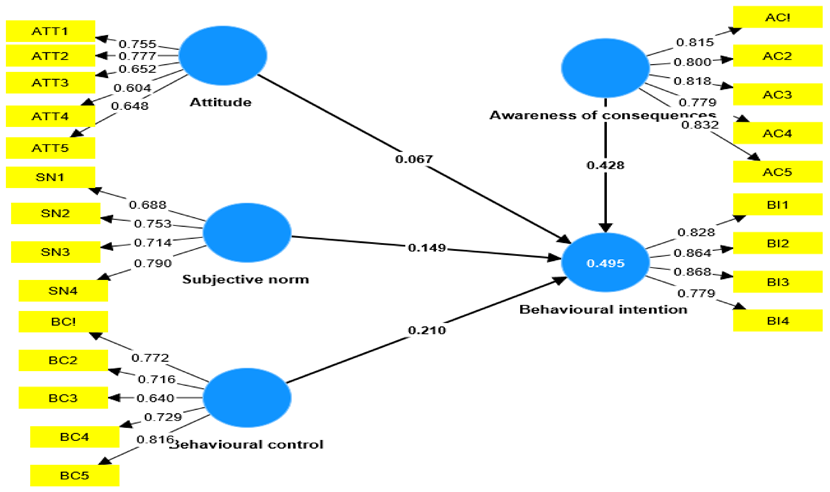

Path Analysis

| Original sample (O) | Sample mean (M) | Standard deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude -> Behavioral intention | 0.067 | 0.077 | 0.073 | 0.927 | 0.354 |

| Awareness of consequences -> Behavioral intention | 0.428 | 0.426 | 0.080 | 5.318 | 0.000 |

| Behavioral control -> Behavioral intention | 0.210 | 0.208 | 0.090 | 2.325 | 0.020 |

| Subjective norm -> Behavioral intention | 0.149 | 0.150 | 0.069 | 2.166 | 0.030 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

6. Theoretical Contributions

7. Managerial Implications

8. Limitation and future research

Acknowledgments

References

- Aboelmaged, M. G. (2020, April). Acceptance of E-waste recycling among young adults: an empirical study. In 2020 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179–211.

- Ajzen, I. (2011). Design and evaluation guided by the theory of planned behavior. Soc psychol Eval, Guilford Publications, 74–100.

- Ajzen, I. (2015). Consumer attitudes and behavior: The theory of planned behavior applied to food consumption decisions. Rivista Di Economia Agrariadi Economia Agraria, 70(2), 121–138. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Christian, J. From attitudes to behaviour: Basic and applied research on the theory of planned behaviour. Curr. Psychol. 2003, 22, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (1999). Distinguishing perceptions of control from self-efficacy: Predicting consumption of a low-fat diet using the theory of planned behavior 1. Journal of applied social psychology, 29(1), 72–90.

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrow, K., Dasgupta, P., Goulder, L., Daily, G., Ehrlich, P., Heal, G., Levin, S., Mäler, K.G., Schneider, S., Starrett, D., & Walker, B. (2017). Are we consuming too much? Sustainability, 18(3), 357–382. [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R. An extension of the theory of planned behaviour in predicting intention to reduce plastic use in the Philippines: Cross-sectional and experimental evidence. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 25, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Ham, S.H.; Hughes, M. Picking up litter: an application of theory-based communication to influence tourist behaviour in protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Bonnes, M.; Fornara, F.; Passafaro, P.; Tronu, G. Planned behavior and “local” norms: an analysis of the space-based aspects of normative ecological behavior. Cogn. Process. 2009, 10, 198–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, V. Z. (2020). Value-Action Gap towards Green Consumer Behavior: A Theoretical Review and Analysis. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT), 8(4), 497-505.

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Negative Word-of-Mouth Communication Intention: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cannière, M. H., De Pelsmacker, P., & Geuens, M. (2009). Relationship quality and the theory of planned behavior models of behavioral intentions and purchase behavior. Journal of business research, 62(1), 82-92.

- Dixit, S.; Badgaiyan, A.J. Towards improved understanding of reverse logistics – Examining mediating role of return intention. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 107, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T.; Ng, E.; Wang, C.-M.; Hsu, M.-L. Normative Beliefs, Attitudes, and Social Norms: People Reduce Waste as an Index of Social Relationships When Spending Leisure Time. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenitra, R.M.; Tanti, H.; Gancar, C.P.; Indrianawati, U.; Hartini, S. Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to explain environemntally responsible behavior in context of nature-based tourism. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 39, 1507–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, T.; Hing, N. Backpacker hostels and their guests: attitudes and behaviours relating to sustainable tourism. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 6, 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Gao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, H. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to understand individual’s energy saving behavior in workplaces. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Ritchie, B.; Wang, J. Non-compliance in national parks: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour model with pro-environmental values. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.; Mariapan, M.; Lin, E.; Bidin, S. Environmental Concern, Attitude and Intention in Understanding Student’s Anti-Littering Behavior Using Structural Equation Modeling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Travelers' pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Trang, H.L.T.; Kim, W. Water conservation and waste reduction management for increasing guest loyalty and green hotel practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajj, A.; Domiati, S.; Haddad, C.; Sacre, H.; Akl, M.; Akel, M.; Tawil, S.; Abramian, S.; Zeenny, R.M.; Hodeib, F.; et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding the disposal of expired and unused medications among the Lebanese population. J. Pharm. Policy Pr. 2022, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. SSituational and personality factors as direct or personal norm mediated predictors of pro-environmental behavior: Questions derived from norm-activation theory. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.A.-T.; Biswas, C.; Roy, M.; Akter, S.; Kuri, B.C. Youth travelers and waste reduction behaviors while traveling to tourist destinations. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 31, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Kim, W. Youth travelers and waste reduction behaviors while traveling to tourist destinations. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Steinhorst, J.; Schmitt, M. Plastic-Free July: An Experimental Study of Limiting and Promoting Factors in Encouraging a Reduction of Single-Use Plastic Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, J.; Chu, G.; Yang, J.; Yu, P. Factors influencing tourists’ litter management behavior in mountainous tourism areas in China. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C., Lin, Y., Connell, J. W., Cheng, H. M., Gogotsi, Y., Titirici, M. M., & Dai, L. (2019). Carbon-based metal-free catalysts for energy storage and environmental remediation. Advanced Materials, 31(13), 1806128.

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.H.; Zhang, L.; He, K. The impact of psychological factors on farmers’ intentions to reuse agricultural biomass waste for carbon emission abatement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juschten, M.; Jiricka-Pürrer, A.; Unbehaun, W.; Hössinger, R. The mountains are calling! An extended TPB model for understanding metropolitan residents' intentions to visit nearby alpine destinations in summer. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A.; Younus, M. Managing plastic waste disposal by assessing consumers’ recycling behavior: the case of a densely populated developing country. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 33054–33066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Is walking or riding your bike when a tourist different? Applying VAB theory to better understand active transport behavior. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 311, 114868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, A. J. (2020). Household behaviour towards waste management–A case study amongst the youth in Parys, South Africa (Doctoral dissertation, North-West University (South Africa)).

- Kumar, A. Exploring young adults’ e-waste recycling behaviour using an extended theory of planned behaviour model: A cross-cultural study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Theory of Planned Behavior: Potential Travelers from China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2004, 28, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Moscardo, G. Understanding the Impact of Ecotourism Resort Experiences on Tourists’ Environmental Attitudes and Behavioural Intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, N. T. P., Anh, T. D., & Ha, N. T. V. Intention and behavior towards bringing your own shopping bags in Vietnam: an Investigation Using the Theory of Planned Behavior. The International Journal of Business Management and Technology, Volume 5 Issue 3 May – June 2021 ISSN: 2581-3889.

- Liu, A.; Ma, E.; Qu, H.; Ryan, B. Daily green behavior as an antecedent and a moderator for visitors’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1390–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, C. (2019). Emergence of plastic pollution on tourism beaches in Zanzibar, Tanzania (Doctoral dissertation). THE TOURISM INDUSTRY AND SOURCES OF WASTES.

- Marek-Andrzejewska, E.M.; Wielicka-Regulska, A. Targeting Youths’ Intentions to Avoid Food Waste: Segmenting for Better Policymaking. Agriculture 2021, 11, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizin, S.; Van Dael, M.; Van Passel, S. Battery pack recycling: Behaviour change interventions derived from an integrative theory of planned behaviour study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 66–82 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matharu, M.; Jain, R.; Kamboj, S. Understanding the impact of lifestyle on sustainable consumption behavior: a sharing economy perspective. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 32, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. Extending the theory of planned behaviour: testing the effects of authentic perception and environmental concerns on the slow-tourist decision-making process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliute-Plepiene, J.; Hage, O.; Plepys, A.; Reipas, A. What motivates households recycling behaviour in recycling schemes of different maturity? Lessons from Lithuania and Sweden. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 113, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloudj, K., Bouarar, A. C., & Mouloudj, S. (2023, May). Extension of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) to predict farmers’ intention to save energy. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2683, No. 1). AIP Publishing.

- Mugiarti, M., Adawiyah, W. R., & Rahab, R. (2022). Green hotel visit intention and the role of ecological concern among young tourists in Indonesia: a planned behavior paradigm. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 70(2), 243-257.

- Nabirye, R. (2018). The effect of beach pollution on tourist satisfaction. Master’s Thesis. UNIVERSITAT DE LES ILLES BALEARS.

- Panwanitdumrong, K.; Chen, C.-L. Investigating factors influencing tourists' environmentally responsible behavior with extended theory of planned behavior for coastal tourism in Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, A.K.; Omar, H.; Tahir, S. The Impact of perceived environmental responsibility on Tourist' intention to visit Green Hotel: The Mediating role of attitude. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 34, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumle, G.; Pikturnienė, I. Predictors of recycling behaviour intentions among urban Lithuanian inhabitants. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Nyaupane, G.P. Understanding Environmentally Responsible Behaviour of Ecotourists: The Reasoned Action Approach. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2016, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Wang, X.; Morrison, A.M.; Kelly, C.; Wei, W. From ownership to responsibility: extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourist environmentally responsible behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmawati, T.; Damayanti, S.; Jati, R.K.; Astrini, N.J. An extended TPB model of waste-sorting intention: a case study of Indonesia. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 34, 1248–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahabuddin; Tan, Q. ; Hossain, I.; Alam, S.; Nekmahmud Tourist Environmentally Responsible Behavior and Satisfaction; Study on the World’s Longest Natural Sea Beach, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmerzler, S.M. Attitudes toward Environmental Conservation in the Kingdom of Tonga: Observed Behavior and Implications for Environmental Education; ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.; Ben David, A. Responsibility and Helping in an Emergency: Effects of Blame, Ability and Denial of Responsibility. Sociometry 1976, 39, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. (1977) Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in experimental social psychology. L. Berkowitz (ed.). San Diego: Academic Press, 221-279.

- Sharp, V.; Giorgi, S.; Wilson, D.C. Delivery and impact of household waste prevention intervention campaigns (at the local level). Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2010, 28, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.A.; Perkins, H.E.; Buckley, R. Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: The effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tour. Manag. 2013, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, W.W.M.; Cheng, I.N.Y.; Cheung, L.T.O.; Chen, Y.; Chow, S.C.F.; Fok, L.; Lo, S.K. Extending the theory of planned behaviour to explore the plastic waste minimisation intention of Hong Kong citizens. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2021, 37, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vina, D., & Mayangsari, L. (2020). The application of theory of planned behavior in single-use plastic bags consumption in Bandung. J. Glob. Bus. Soc. Entrep.(GBSE), 6, 124–137.

- Vlek, C.; Keren, G. Behavioral decision theory and environmental risk management: Assessment and resolution of four ‘survival’ dilemmas. Acta Psychol. 1992, 80, 249–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, G.; Ren, G.; Feng, Y. Analysis of the environmental behavior of farmers for non-point source pollution control and management: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P.; Hu, H. The theory of planned behavior as a model for understanding tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors: The moderating role of environmental interpretations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Cai, H.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z. Smart household electrical appliance usage behavior of residents in China: Converging the theory of planned behavior, value-belief-norm theory and external information. Energy Build. 2023, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ji, C.; He, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Tourists’ waste reduction behavioral intentions at tourist destinations: An integrative research framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 25, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y. Consumers’ Intention to Bring a Reusable Bag for Shopping in China: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweneboah-Koduah, E.Y.; Adams, M.; Nyarku, K.M. Using Theory in Social Marketing to Predict Waste Disposal Behaviour among Households in Ghana. J. Afr. Bus. 2019, 21, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Liu, H.-H. Integrating Altruism and the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Patronage Intention of a Green Hotel. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 39, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Pu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z. Consumer’s Waste Classification Intention in China: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Pang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, S.; Fu, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Environmental remediation of heavy metal ions by novel-nanomaterials: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ling, M.; Lu, Y.; Shen, M. Understanding Household Waste Separation Behaviour: Testing the Roles of Moral, Past Experience, and Perceived Policy Effectiveness within the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Sustainability 2017, 9, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., & Hu, Y. (2023). Nature-inspired awe toward tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior intention intention. Tourism Review.

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers' intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers' Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Qiu, H.; Morrison, A.M. Applying a Combination of SEM and fsQCA to Predict Tourist Resource-Saving Behavioral Intentions in Rural Tourism: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W., Qiu, H., Morrison, A. M., Wei, W., & Zhang, X. (2022). Landscape and Unique Fascination: A Dual-Case Study on the Antecedents of Tourist Pro-Environmental Behavioural Intentions. Land, 11(4), 479. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Romero, S.B.; Qin, X. An extension of the theory of planned behavior to predict pedestrians’ violating crossing behavior using structural equation modeling. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 95, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age group | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Younger than 20 | 58 | 21.4 |

| 21 – 30 | 151 | 55.7 |

| 31 - 40 | 28 | 10.3 |

| 41 - 50 | 17 | 6.3 |

| 51 - 60 | 9 | 3.3 |

| 60 + | 8 | 3.0 |

| Total | 271 | 100.00 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 212 | 78.2 |

| Female | 59 | 21.8 |

| Total | 271 | 100.0 |

| Single | 203 | 74.9 |

| Married | 61 | 22.5 |

| Widow/ Widower | 2 | .7 |

| Divorced | 5 | 1.8 |

| Total | 271 | 100.0 |

| Education | ||

| Primary School | 0 | 0 |

| Prep. School | 3 | 1.1 |

| High School | 127 | 46.9 |

| University |

118 | 43.5 |

| Post graduate |

18 | 6.6 |

| Other | 5 | 1.8 |

| Total | 271 | 100.0 |

| No. of visits to beaches | ||

| 1 times | 180 | 66.4 |

| 1-4 times | 46 | 17.0 |

| 5-10 times | 19 | 7.0 |

| 11-15 times | 26 | 9.6 |

| More than 15 times | 271 | 100.0 |

| Total | 180 | 66.4 |

| Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 4.332 | 1.0868 |

| Subjective norms | 3.925 | 1.31725 |

| Perceived behavioral control | 3.934 | 1.309 |

| Awareness of consequences | 4.628 | .6364 |

| Behavioral intention | 4.675 | 0.56675 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).