1. Introduction

In recent times, the domain of

mental health has witnessed substantial progress, specifically in the realm of

digital platforms and technolo- gies that are designed to offer assistance and in- terventions

for individuals afflicted with mental

health ailments1,2,3,4-9. These platforms possess the capacity

to transform mental

health care de- livery, offering

accessible and personalized solu- tions to a wide range of users 10–16,1. However, the design

and implementation of these platforms must be guided

by a user-centred approach to en- sure their

effectiveness and user satisfaction5,16–18. The AMGR-I mental

healthcare pilot platform

is one such that aims to address the needs of in- dividuals with mental

health disorders. It inte- grates community, education, cloud services and healthcare sub-platforms into a comprehensive so- lution. The platform recognizes the importance of user experience and satisfaction, as users now view

products and services as sources of plea- sure, enjoyment, engagement, and

embodiment. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the evolv- ing needs

and expectations of users early

on dur- ing the design process19–22. Previous

studies have highlighted the significance of user-centred design in the development of mental health

platforms and digital health

generally23–29. For example,

re- search on mental health chatbots has emphasized the importance of exploring user experience and satisfaction through the lens of

technology accep- tance theories. Additionally, studies on e-mental health interventions have emphasized

the need for platforms to be tailored

to the preferences and de- mands of users16,30–33. These findings underscore the importance of

incorporating user-centred de- sign principles in the development of the AMGR-I pilot platform.

Furthermore, the field of social network sites (SNSs) has attracted

significant attention from re-

searchers, highlighting the affordances and reach of these platforms34–36. Understanding the fea- tures and dynamics of SNSs can inform the

design and functionality of the social networking and community component of the AMGR-I

platform. Additionally, research

on the relationship between social

networks and mental health can provide in- sights into the potential benefits

of incorporating community

and social networking features into mental

health platforms35,37,38. To ensure the ef- fectiveness and user

satisfaction of the AMGR-I pilot platform, it is essential to conduct participa- tory design research with the

targeted users. By involving potential future

users in the design pro- cess, the platform can be tailored to meet their specific needs

and preferences. This

study will of- fer

valuable insights into the anticipated and in-

tentional user experience from the standpoint of the intended audience, ensuring that

the platform aligns with their expectations.

The design and information structure of an in-

terface facilitate user navigation and comprehen- sion of information, reducing

cognitive burden during interactions39.

To achieve

this objective, various approaches and methods can be employed

to ensure that the structure and information

ar- chitecture are tailored

to the needs and expecta- tions of the intended

users. Many user

experience design and research methods exist40–42 and the se-

lection of the most appropriate method for each

stage of the design process

is critical. A combina-

tion of user experience and user-centred method- ologies were utilized in the research, conceptual- ization, and design

of the AMGR-I platform, par- ticularly participatory design.

Participatory de- sign, also commonly referred to as co-design or co-operative design43–47, is more of a process

than an outcome, consisting of three phases: (1) under- standing and

problem definition, (2) generating

potential solutions, and

(3) testing these

ideas by involving potential future users of the

intended product-service during the

design process 48. The aim is to comprehend the mindsets,

attitudes, and behaviours of the

targeted users or participants through mindful, playful, thoughtful, and engag- ing innovative and

experimental approaches that reveal insights. These insights

identify potential "pain points" where changes are necessary early on

in the design and development process. While

variations exist in the execution of participatory

design across different domains, including health-

care design, these variations must (1) engage po- tentially targeted users, whether

actual users or hypothetical

personas, which will influence the design of the product-service and the

outcomes of the design process and (2) adhere to the core principles of

co-design47,49–52;

- (a)

Inclusive: for better results in simulations and testing solutions, it should be inclusive and a representation of all groups that will be impacted by the product service and harness the result- ing decisions, thought processes, experiences and feedback.

- (b)

Participative: the process must be open, empathetic and responsive with a high degree of engagement by participants to interact and share gained knowledge from lived experience and gen- erate thoughts and ideas through workshops, sim- ulations, exercises, activities, chats, etc.

- (c)

Iterative: continuous re-evaluation and test- ing of ideas and solutions throughout the process, adapting to changes as they emerge from new scenarios with openness to creativity and explo- ration, and the possibility of failure during numer- ous attempts. The effectiveness of the interaction stages and engagement can be tested for effective- ness and pools of ideas and solutions fine-tuned to context and their potential impact based on the original objective of the task.

- (d)

Equivalent: all attending participants are regarded equal in expertise of their experience with set strategies applied to eliminate inequal- ity because the product-service experience by the user is always a true value of its own experience with varying levels of ease or understanding, re- gardless of novice or expertise.

- (e)

Goal Oriented: regardless of the intention of the process, whether to design, or evaluate some- thing existing it is set to achieve a set of out- comes where the most promising of solutions can be revisited and tested or experimented with in successive phases of the participatory process.

In recent times, there has been an

increasing inclination among users

to go beyond mere prod- uct and service functionality and

delve into the realm of experience,

embodiment, and engage- ment. This has given rise to the development of user experiences that are both delightful and en-

gaging. As a result, user experience has become the standard for industry benchmarks, with companies now prioritizing it over the

previous em- phasis on usability and product functionality53–55. Presently, design trends and consumer demand re-

volve around products that can

seamlessly inte- grate with and

cater to the users’ everyday lives.

This is in contrast to products that merely sup- port the completion of everyday tasks.

The reason for this

shift is that

functionality alone is no longer sufficient to compete with the

immersive expe- riences of engagement, embodiment, and plea- sure56–58.

Designers and companies must adapt

to the increasing demand for

user experience and its

integration into the design

of product-service systems to

remain competitive. The pursuit of delightful

user experiences is an essential

objec- tive in the design of user-product interactions and serves as a

measure of success for the over- all

user experience59–63. Consequently,

user ex- perience has become the focal point of product design, research, and industry,

underscoring the significance

of this research64,65.

This paper outlines the design,

structure, and evaluation of

participatory design research aimed at improving user-centred design for

digital men- tal health through the use of the AMGR-I pilot project design.

By engaging with

potential future users, this

research provides insights into an

al- ternative perspective on product user experience, encompassing both

anticipated and intentionally designed aspects. The motivation behind

this re- search lies in the necessity to bridge the knowledge

gaps surrounding expected user experiences dur- ing the early stages of design,

to make informed decisions regarding the design of digital mental

health solutions for the AMGR-I platform. By adopting a user-centred design

approach and in- corporating insights from previous

research, the platform can effectively meet the evolving

needs and expectations of its users.

Through participa- tory design

research, the platform can be tailored

to provide a personalized and engaging user ex-

perience. The findings from this research can in-

form the development of new digital mental

health platforms and improve existing

ones. Overall, this research contributes to a better

understand- ing of user-centred design through participatory design research in the

context of mental health platforms,

ensuring that the AMGR-I platform meets the evolving needs of its users.

1.1. The AMGR-I Platform

With the advancement of technology, an assort- ment of design

tools and techniques have swiftly emerged, each possessing its

distinct advantages. Consequently, the selection of a tool relies on the

specific task at hand during a particular phase of project development, as well as the limitations in- herent in each tool. The creation of the AMGR-I platform involved a blend of design research

meth- ods and tools. During the initial stage of design, preliminary versions of the platform

were explored and crafted

through basic paper sketches and prototypes. Subsequently,

these initial designs were transformed into low-fidelity and mid-fidelity digital wireframes following various iterations of ideas and design concepts. To ensure interactiv-

ity

and examine the

anticipated user-platform in- teraction, high-fidelity and

detailed design pro- totypes were created using Figma66. During

the evaluation phase, high-fidelity interactive proto- types were employed

to assess interaction, infor- mation architecture, user

experience, and partic- ipant engagement.

The design of the mental health

platform in-volves the identification of interrelated variables, as it is a

structured information system. Con- sequently,

the structuring of these variables to

determine the platform’s functionalities requires careful consideration of

information design to en- hance efficiency and user experience. A key fac- tor in achieving an efficient

user experience is the establishment of a solid information archi- tecture19,67–71. The platform’s structure was de- vised to facilitate design

implementation across four distinct

categories: (1) Social or Commu- nity - a sub-platform dedicated to community so- cial networking for patients, supporters, profes- sionals, and relevant

organizations; (2) Health

- a sub-platform enabling

interaction between patient users and healthcare professionals

and providers; (3) E-Learning - a

sub-platform for educational content, projects, programs, and health

informa- tion; and (4) Cloud - an interconnected cloud storage service

promoting easy access to shared patient-doctor information, as well as user-service

provider resources such as healthcare providers, educational information providers, insurance, etc. Each category encompasses a range

of subcat- egories or functionalities that contribute to the overall user experience. The platform incorpo-

rates various design techniques and principles from cognitive psychology to

effectively apply psychological principles to the design process, in- cluding

Gestalt principles and recognition pat- terns. In the social community category, the platform aims to create a

social networking and community environment where users can interact with other

members for support and shared ex- periences. The health category focuses on

men- tal health-related features

like mental health care and management, optionally with

healthcare pro- fessionals. The e-learning category provides ed- ucational and informational content, including virtual classrooms, programs and mental

health- related content. The

cloud category binds and syncs with all the other three categories, allow- ing

users and providers easy and reliable inter- connected access across the different platform

seg- ments.

2. Methods

For the present study, we utilized

G*Power (version 3.1.9.6)72. Based on the nature of our re- search questions and the data types anticipated,

we

opted for a priori analysis

to compute the re-

quired sample size, with T-tests;

Means: the dif- ference between two dependent means

(matched pairs). This choice aligned with our aim of com- paring paired data metrics

before and after a de- sign change. The input parameters

specified were; effect size

(dz) = 0.5,

α err prob

= 0.05, and power

(1-β err prob) = 0.95. With these parameters specified, we proceeded

to compute the required

sample size. The output parameters were; non- centrality parameter δ =

3.35, critical t = 1.68, df = 44 and total sample size = 45 with actual power = 0.95.

2.1. Study Setup and Participants:

The study was conducted in a Spanish uni- versity setting leveraging the diverse and informed population of architecture, engineering, ergonomics and design students. A total of 45 students participated, providing a balanced mix of expertise and fresh perspectives on the AMGR- I healthcare digital platform design and perceived user experience.

2.1.1. Participatory Design Approach

Workshops and Activities: A series of partici- patory design workshops were organized, and fa- cilitated by experienced collaborating instructors and researchers from both academia and indus- try. The workshops included brainstorming ses- sions, prototype development, and iterative feed- back loops. These activities aimed to generate creative solutions and refine the platform’s design based on students’ feedback and inputs.

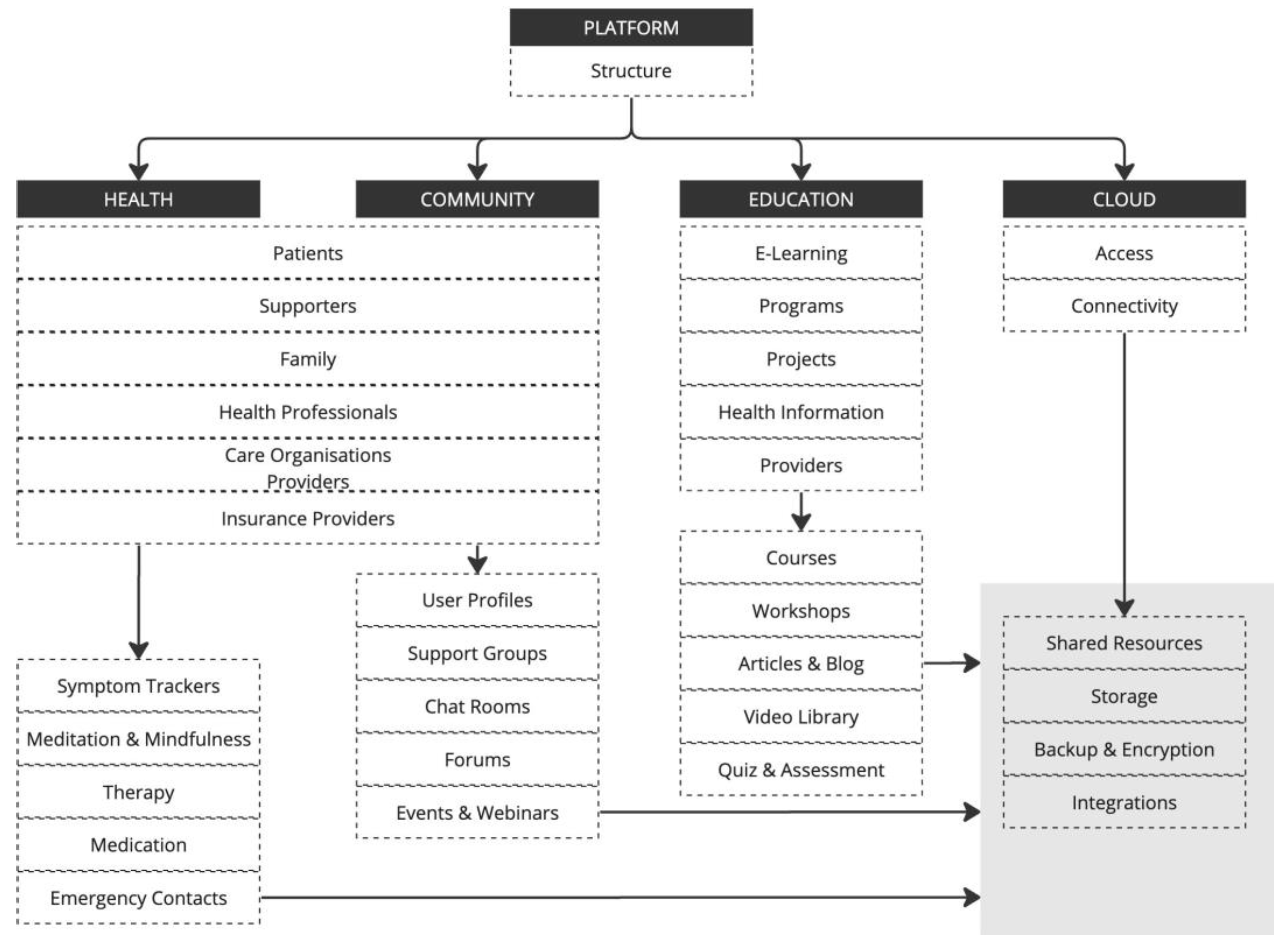

Figure 1.

The conceptual structure of the AMGR-I platform.

Figure 1.

The conceptual structure of the AMGR-I platform.

Tools and Techniques: Various tools such as de- sign thinking, user journey mapping, and proto- typing were employed to facilitate the co-creation process and visualize design ideas. Students were encouraged to collaborate, share insights, and provide constructive feedback throughout the de- sign phase.

Reflection and Consolidation: Post-workshop reflection sessions were held to consolidate the findings and insights gathered during the partici- patory design workshops and activities. This step ensured that all valuable input was documented and considered in the subsequent design itera- tions.

2.2. Data Analysis

Collected data, both qualitative (from work- shops, think-aloud protocols, and interviews) and quantitative (from usability tests), underwent rig- orous analysis. Quantitative data from the usabil- ity studies were analyzed using statistical soft- ware, providing insights into the platform’s effi- ciency, effectiveness, and user satisfaction. Qual- itative data, including interview transcripts and observational notes, were coded and subjected to thematic analysis using software to identify pat- terns, insights, and areas for enhancement.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

All participants were briefed on the study’s purpose, procedures, the nature of their involve- ment, privacy and potential implications. In- formed consent was obtained, ensuring voluntary participation, anonymity, and the right to with- draw at any stage, compliant with both univer- sity and national regulations. Data confidentiality and secure storage were maintained throughout the research. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Blithe Research Initiative (BRI) (BRI.581506.18215/1/1).

By adopting this mixed-method approach, combining participatory design with usability testing, the study aimed to offer comprehen- sive insights into the design, functionality, and user experience of the healthcare digital plat- form, leveraging the unique perspective of design students. The multifaceted perspective on the healthcare digital platform’s design and user ex- perience ensured a user user-centric outcome that aligns with real-world needs and expectations.

3. Results

The participatory design study conducted among 45 university students for the AMGR-I digital mental health care platform yielded valu- able insights into the preferences, needs, and concerns of potential users. The following sec- tions detail the significant findings, potential suggestions, and counter-arguments.

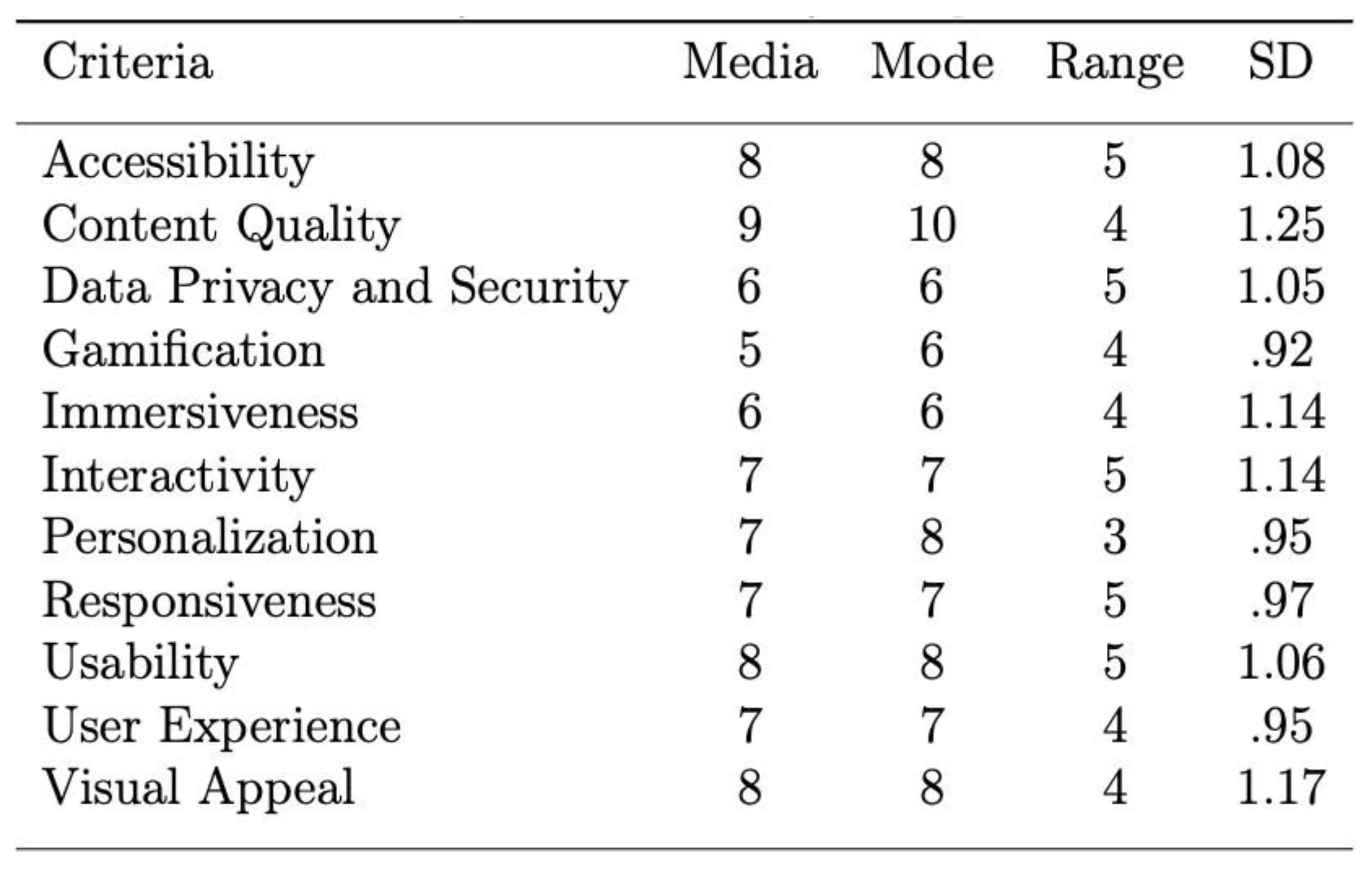

A comprehensive descriptive analysis was con- ducted to extract insights from the gathered data. The following summarizes the central tenden- cies and spread of scores across distinct criteria for Median (M), Mode (Mo), Range (Range=x max x min) and Standard Deviation (SD/σ).

Performers analysis based on average score identified top performers as content quality (8.89), usability (7.91) and accessibility (7.87); and bottom performers as gamification (5.20), immersiveness (5.98), data privacy and security (5.89). From this analysis, it’s evident that par- ticipants found the platform’s content quality, usability, and accessibility to be its strongest aspects. On the other hand, gamification, immer- siveness, data privacy and security were identified as areas that might require improvement or fur- ther refinement.

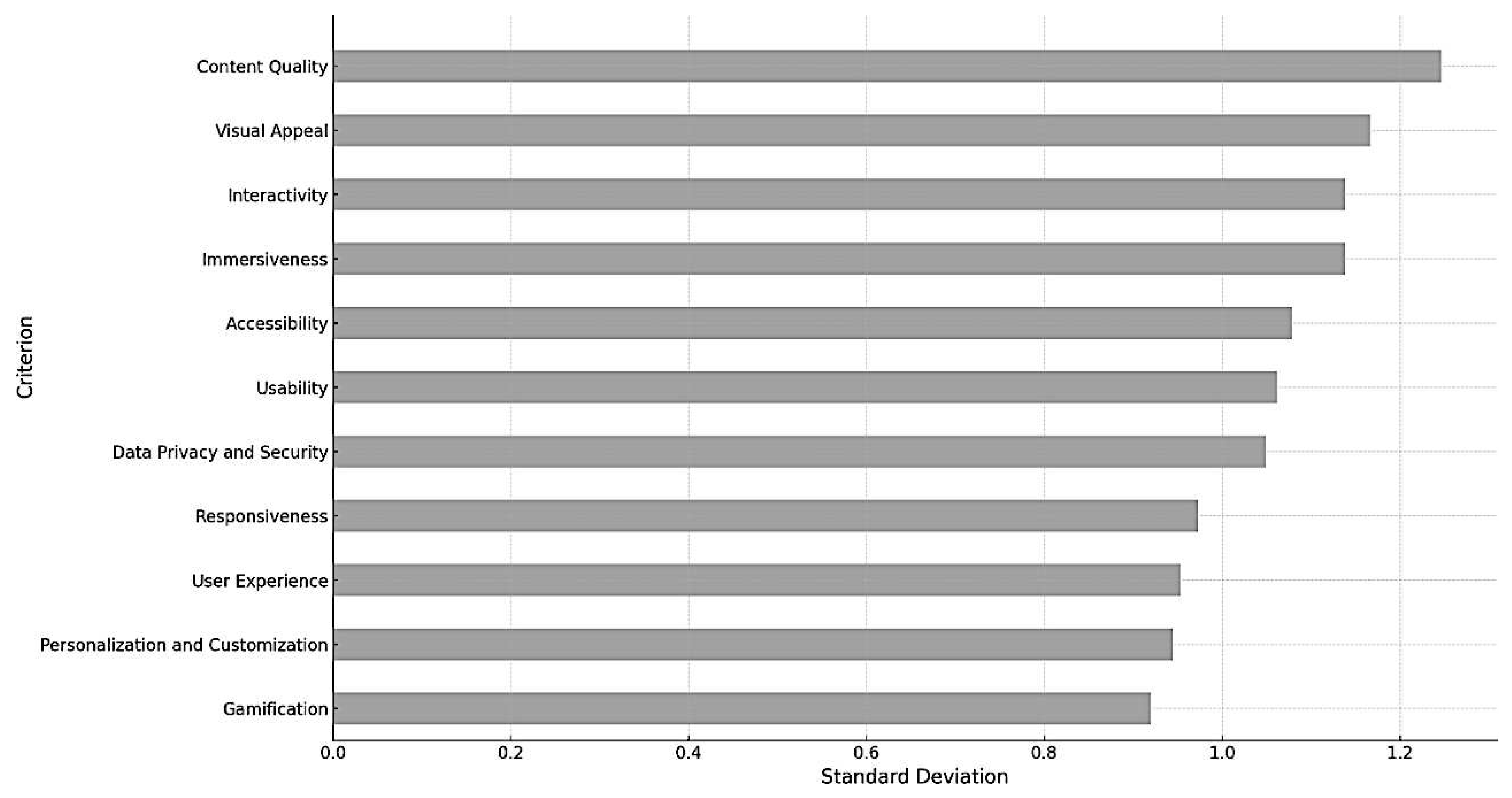

The bar chart visually represents the stan- dard deviation for each criterion, providing in- sights into the feedback consistency of the partic- ipants. Content quality and immersiveness have relatively high standard deviations, indicating a wider spread of scores and potentially diverse opinions among participants about these criteria. Gamification, personalisation and customization have lower standard deviations, suggesting more consistent feedback among participants regarding these criteria. Diverse opinions on certain features were expected due to the varied experiences and needs of the participants, especially for a men- tal health platform. A higher standard deviation might suggest a need for customization options or additional user segmentation for those particular features.

In the anomaly detection analysis, some partic- ipants (S-02, S-12, S-19, S-27, S-36 and S-38) were identified as potential outliers based on their feed- back scores. These participants provided feedback scores that deviated significantly from the general trend. Understanding the reasons behind these deviations can provide valuable insights. For in- stance, in cases where a particular user found gamification to be less satisfactory than most, un- derstanding their perspective could uncover spe- cific areas for improvement.

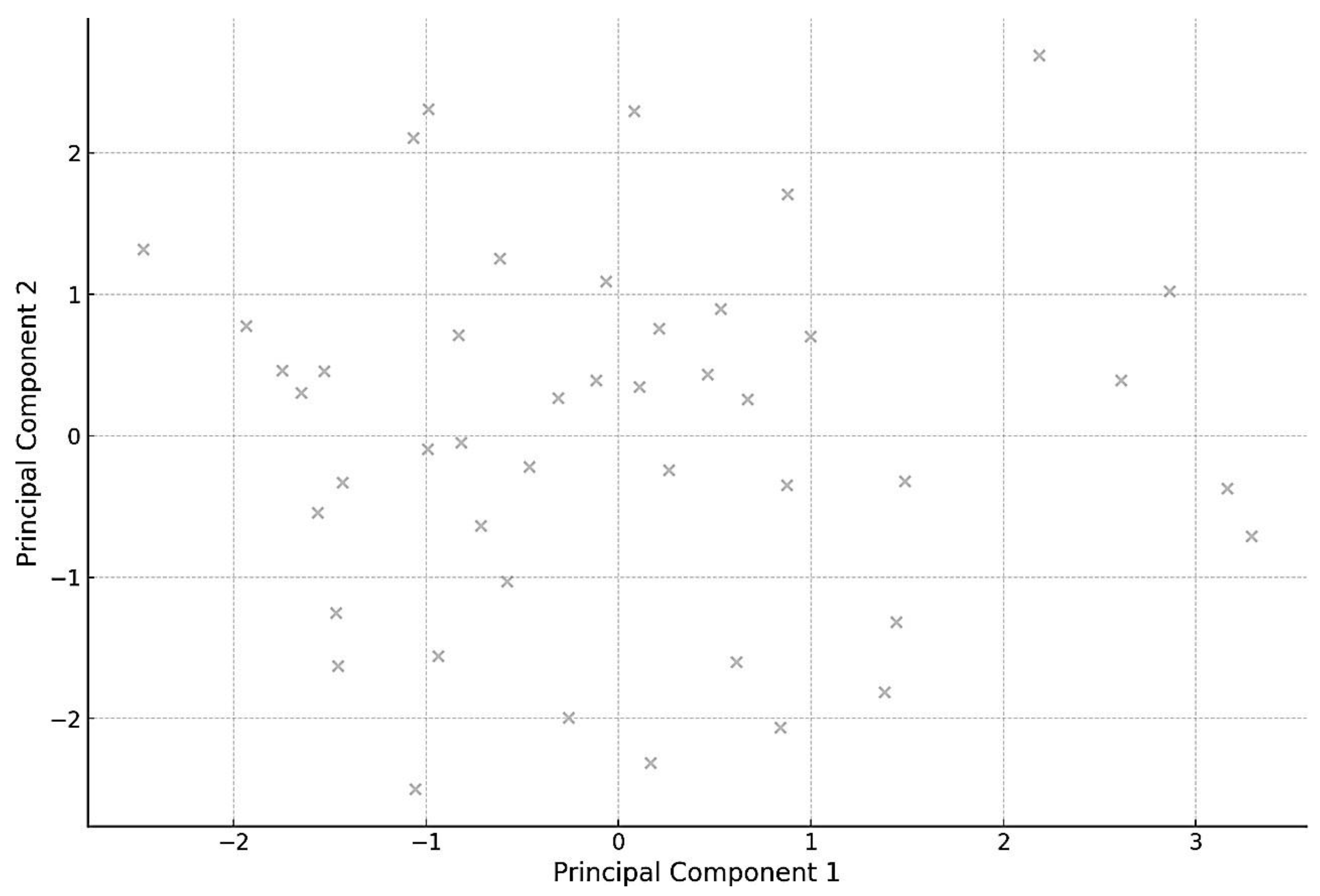

Basic Cluster Analysis was also conducted to visually examine the data and see if any appar- ent groupings or patterns existed in how students scored different criteria. Using Principal Compo- nent Analysis (PCA), the dimensionality of our data set was reduced to two principal components for visualization purposes. The scatter plot rep- resents the scores of the 45 students projected onto these two principal components. There don’t seem to be any distinct clusters, suggesting that the participants’ feedback is relatively dispersed without clear groupings. A few points are far- ther from the main concentration, which might correspond to the outliers we identified earlier. This basic visual representation indicates a di- verse range of feedback from the participants. While there aren’t distinct groupings, the vari- ability in feedback emphasizes the importance of considering individual user needs and preferences, especially in the context of a mental health plat- form.

Figure 2.

Summary of AMGR-I study descriptive statistics.

Figure 2.

Summary of AMGR-I study descriptive statistics.

Figure 3.

Feedback Consistency. Standard Deviation for Each Criterion.

Figure 3.

Feedback Consistency. Standard Deviation for Each Criterion.

Figure 4.

Basic Cluster Analysis using CPA.

Figure 4.

Basic Cluster Analysis using CPA.

3.1. Key Insights from Participatory Design Workshops

3.1.1. Brainstorming Sessions

A total of n=138 distinct ideas were generated during the brainstorming sessions. Among the most recurrent themes were enhancing user pri- vacy, incorporating personalized therapeutic con- tent, and gamifying certain aspects of the plat- form to improve engagement. A few students ex- pressed concerns about gamifying the platform, fearing it might trivialize the platform’s primary purpose. Additionally, while AI-driven therapy sounded promising, there were concerns about po- tential misdiagnoses without human oversight.

3.1.2. Prototype Development and Feedback

Three primary prototypes were developed, each focusing on a different design theme — minimal- ist, illustrative, and immersive. The immersive design received the most positive feedback, with students appreciating its intuitive user interface. Many students suggested integrating virtual real- ity or augmented reality components into the im- mersive design, envisioning a therapeutic virtual space for users. There were reservations about this approach’s cost implications, as well as con- cerns regarding the long-term impact on users. Some believed that excessive immersion might de- ter users from seeking face-to-face therapy or real- world interaction.

Interface and Usability: The majority of the students (n=38 out of 45) emphasized the im- portance of a user-friendly interface with intu- itive navigation. Particularly, prioritizing a min- imalist design aesthetic with clear and concise instructions to ensure users can easily navigate through the platform. While simplicity is valued, it’s essential not to oversimplify to the extent that crucial functionalities are missed or the platform looks underdeveloped.

Personalisation and Customization: 40 (n=40 out of 45) participants expressed a desire for a platform that offers personalized recommenda- tions and treatment plans based on individual user profiles. It was also suggested to incorporate machine learning algorithms to curate personal- ized content and treatment suggestions for users. However, over-reliance on algorithms might over- look the nuances of human emotions and condi- tions. Thus, it would be pivotal to ensure a bal- ance between automated recommendations and expert human oversight.

Data Privacy and Security: A significant con- cern among participants (n=35 out of 45) was the privacy, security and confidentiality of their data. The implementation of end-to-end en- cryption and regular communication with users about how their data is used and protected was greatly valued. Enhancing security might some- times compromise the platform’s usability. It’s crucial to strike a balance.

3.1.3. Tools and Techniques Feedback

Design Thinking and Prototyping: Utilizing the design thinking approach fostered creativity and problem-solving, as reported by students (n=42). Adopting a human-centric perspective, the de- sign thinking approach allowed students to em- pathize better with potential users of the plat- form. This has directed us to continue leveraging design thinking in future iterations and involve a diverse group of stakeholders for a broader per- spective. It was proposed to develop a moderated peer-support forum within the platform, where users could share their experiences and coping strategies. Some students raised valid concerns about the potential risks and liabilities of such forums, emphasizing the need for strong modera- tion and community guidelines. Design thinking, while effective, can sometimes prolong the design phase due to its iterative nature. It’s crucial to ensure the process remains time-efficient.

User Journey Mapping: Students (n=37) found the user journey mapping technique beneficial in visualizing the user experience from start to end. However, mapping the user journey highlighted friction points, notably during the sign-up process and initial therapeutic content selection. Stream- lining the registration process and introducing a tutorial or onboarding sequence for first-time users were among the proposed solutions. Reg- ularly updating the user journey maps to reflect changes in user behaviour and platform features is also crucial. User journey maps are just one tool among many, and over-reliance can poten- tially limit the scope of understanding users’ holis- tic experiences. While many supported the tuto- rial idea, some argued that over-simplifying the interface might make the platform appear less so- phisticated or comprehensive.

3.1.4. Reflection and Consolidation Insights

Comprehensive Documentation: The post-workshop reflection sessions ensured that 95% of the feedback and insights were documented and integrated into the subsequent design phase. This helped maintain a digital repository of these reflections to track changes and improvements over time. However, while documentation is essential, over-documentation can lead to infor- mation overload and potential overlooking of critical feedback.

Collaborative Spirit: The participatory nature of the study cultivated a sense of community among the students, with participants (n=41) ex- pressing a heightened sense of ownership and in- vestment in the platform’s outcome. Regularly in- volving end-users in the design and feedback pro- cess keeps the design and platform aligned with user needs. Continuous involvement might lead to design inconsistencies if feedback is not curated and streamlined effectively.

There was unanimous agreement on the neces- sity of prioritizing user privacy and data security. While innovative features like VR and AI-driven therapy garnered enthusiasm, there was also a consistent voice of caution to ensure the platform remained accessible, and grounded, and did not lose sight of its core therapeutic objectives. Feed- back emphasized a balance between technological innovations and genuine mental health support.

4. Discussion

The design and evaluation of healthcare digital platforms require a user-centred approach to en- sure their effectiveness and user satisfaction. Par- ticipatory design plays a crucial role in under- standing the needs and preferences of users, as well as evaluating the design and user experience of these platforms. Participatory design research involves actively involving the intended users in the design process73. This approach recognizes the unique needs and preferences of users and en- sures that the platform is tailored to meet their requirements74. By engaging users in the design process, the platform can be more user-friendly, intuitive, and aligned with their expectations75. The findings from participatory design research can inform the development of digital platforms that are more effective in supporting healthcare interventions76. The evaluation of healthcare dig- ital platforms through participatory design has several benefits. Firstly, it ensures that the plat- form meets the specific needs and preferences of the target users77. By involving users in the design process, the platform can be customized to address their unique challenges and require- ments78. Secondly, it enhances user satisfaction and engagement with the platform79. By consid- ering user feedback and preferences, designers can create a platform that is intuitive, user-friendly, and enjoyable to use80. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of sustained engagement and posi- tive health outcomes79. Furthermore, participa- tory design and usability studies contribute to the development of user-centred healthcare digi- tal platforms81. By actively involving users in the design process, the platform becomes more inclu- sive and accessible to a diverse range of users82. This is particularly important for individuals with impairments or disabilities, as their specific needs and challenges can be addressed through partici- patory design approaches73.

The platform can influence the organization and functionality of a system through interaction and information architecture. This arrangement serves as the central component of usability and user experience, as users carry out their tasks and engage with the system. The approach to de- sign, which is centred around the user, incorpo- rates various strategies for participation and mul- tiple stages of evaluation. This approach has al- lowed us to select the most promising and antic- ipated user experiences from a range of options. Certain features and functionalities of the plat- form were chosen for further redesign, iteration, and development due to a lack of motivation from the target audience to engage with them, or be- cause they did not yield the expected user ex- perience. To achieve this, a combination of es- tablished methods for user experience design and usability evaluation were employed, as detailed in this paper. These methods include participatory design, controlled experiments, heuristic evalu- ation, workshops or sessions, performance mea- surement, thinking aloud, observation, question- naires and surveys, interviews, focus groups, and user feedback. Future research, experiments, and design stages of the AMGR-I platform will delve deeper into the topics of usability, user experience, and interaction.

The participatory design study conducted among 45 university students for the AMGR- I digital mental health care platform yielded valuable insights into the preferences, needs, and concerns of potential users. The study em- ployed a series of participatory design workshops, including brainstorming sessions, prototype de- velopment, and iterative feedback loops. Various tools and techniques, such as design thinking and user journey mapping, were used to facilitate the co-creation process. Post-workshop reflection sessions were held to consolidate the findings and insights gathered during the participatory design activities. The brainstorming sessions generated a total of 138 distinct ideas, with recurring themes focusing on enhancing user privacy, incorporating personalized therapeutic content, and gamifying certain aspects of the platform to improve en- gagement. However, concerns were raised about the potential trivialization of the platform’s primary purpose through gamification and the risk of misdiagnoses without human oversight in AI-driven therapy. Prototype development and feedback resulted in three primary prototypes, each focusing on a different design theme. The immersive design received the most positive feed- back, with students appreciating its intuitive user interface. Suggestions were made to integrate vir- tual reality or augmented reality components into the immersive design, envisioning a therapeutic virtual space for users. However, concerns were also raised about the cost implications and the potential long-term impact on users, as excessive immersion might deter users from seeking face- to-face therapy or real-world interaction. The majority of the students emphasized the impor- tance of a user-friendly interface with intuitive navigation. They prioritized a minimalist design aesthetic with clear and concise instructions to ensure easy navigation through the platform. However, it was noted that oversimplification should be avoided to prevent crucial functionali- ties from being missed or the platform appearing underdeveloped. Personalisation and customiza- tion were highly valued by the participants, with many expressing a desire for a platform that offers personalized recommendations and treat- ment plans based on individual user profiles. It was suggested to incorporate machine learning algorithms to curate personalized content and treatment suggestions. However, the need for a balance between automated recommendations and expert human oversight was emphasized to avoid overlooking the nuances of human emotions and conditions.

Data privacy and security were significant con- cerns among the participants. They emphasized the importance of implementing end-to-end en- cryption and regularly communicating with users about how their data is used and protected. How- ever, it was acknowledged that enhancing security might sometimes compromise the platform’s us- ability, and a balance needs to be struck. Privacy protection is another crucial aspect to consider in the design and evaluation of healthcare digital platforms. Users need to feel confident that their personal information is secure and protected when using these platforms. Incorporating robust pri- vacy measures and ensuring compliance with data protection regulations is essential to build trust and encourage user engagement83.

The use of design thinking and prototyping was reported to foster creativity and problem-solving among the participants. The human-centric per- spective facilitated by design thinking allowed students to better empathize with potential users of the platform. It was proposed to develop a moderated peer-support forum within the plat- form, where users could share their experiences and coping strategies. However, concerns were raised about the potential risks and liabilities of such forums, highlighting the need for strong moderation and community guidelines. It was also noted that design thinking, while effective, can sometimes prolong the design phase due to its iterative nature, and efforts should be made to ensure time efficiency. User journey mapping was found beneficial in visualizing the user ex- perience from start to end. It highlighted friction points, such as during the sign-up process and ini- tial therapeutic content selection. Proposed solu- tions included streamlining the registration pro- cess and introducing a tutorial or onboarding se- quence for first-time users. Regularly updating the user journey maps to reflect changes in user behaviour and platform features was also empha- sized. However, it was noted that over-reliance on user journey maps can potentially limit the scope of understanding users’ holistic experiences, and the platform’s sophistication and comprehen- siveness should not be compromised. The post- workshop reflection sessions ensured that 95% of the feedback and insights were documented and integrated into the subsequent design phase. This comprehensive documentation helped maintain a digital repository of reflections to track changes and improvements over time. However, it was ac- knowledged that over-documentation can lead to information overload and potential overlooking of critical feedback. The participatory nature of the study cultivated a sense of community among the students, with a heightened sense of ownership and investment in the platform’s outcome. Reg- ularly involving end-users in the design and feed- back process was seen as crucial to aligning the design and platform with user needs. However, it was noted that continuous involvement might lead to design inconsistencies if feedback is not curated and streamlined effectively.

In conclusion, the participatory design study among 45 university students for the AMGR-I digital mental health care platform provided valu- able insights into the preferences, needs, and con- cerns of potential users. The study employed a series of participatory design workshops, in- cluding brainstorming sessions, prototype devel- opment, and iterative feedback loops. Various tools and techniques, such as design thinking and user journey mapping, were used to facilitate the co-creation process. Post-workshop reflection ses- sions were held to consolidate the findings and insights gathered during the participatory design activities. Participatory design is vital for evalu- ating the design and user experience of healthcare digital platforms. By actively involving users in the design process and conducting usability stud- ies, designers can create platforms that meet the specific needs and preferences of users, enhance user satisfaction and engagement, and ensure ac- cessibility and privacy protection. The insights gained from these studies contribute to the de- velopment of user-centred healthcare digital plat- forms that effectively support healthcare interven- tions and improve health outcomes. The study revealed key insights regarding the importance of user privacy, personalized content, and gami- fication in the platform’s design. It highlighted the need for a user-friendly interface with intu- itive navigation, personalized recommendations and treatment plans, and robust data privacy and security measures. The study also emphasized the value of design thinking and prototyping in foster- ing creativity and problem-solving, as well as user journey mapping in visualizing the user experi- ence. The comprehensive documentation and col- laborative spirit cultivated throughout the study were seen as essential for maintaining a digital repository of insights and ensuring a sense of own- ership among the participants. The findings and suggestions from this study can inform the fur- ther development and refinement of the AMGR-I digital mental health care platform. It is crucial to strike a balance between technological innova- tions and genuine mental health support, ensuring that the platform remains accessible, grounded, and aligned with its core therapeutic objectives. Future iterations should continue to leverage par- ticipatory design methods and involve a diverse group of stakeholders for a broader perspective. By prioritizing user needs and preferences, the AMGR-I platform can provide effective and user- centric digital mental health care services.

Acknowledgements

The author discloses partially utilizing genera- tive AI and/or LLM tools in copy-editing the arti- cle to improve its language, academic writing style and readability, including audio-to-text transcrip- tion with Google Cloud Speech-to-Text (version 6.0.2, from Google, 2023). This mirrors standard tools already employed in academic research and uses existing author-created material, rather than generating wholly new content. It also addresses the author’s linguistic challenges faced as a non- native English speaker. The author remains re- sponsible for the work and accountable for its ac- curacy, integrity, and validity.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- J. Torous, L. Roberts, ‘Needed Innovation in Digi- tal Health and Smartphone Applications for Mental Health: Transparency and Trust’, JAMA psychiatry 74 (2017). [CrossRef]

- D. Ben-Zeev, D. C. Atkins, ‘Bringing digital mental health to where it is needed most’ 1 (2017) 849–851. [CrossRef]

- D. Ben-Zeev, S. M. Schueller, M. Begale, J. Duffecy, J. M. Kane, D. C. Mohr, ‘Strategies for mHealth Re- search: Lessons from 3 Mobile Intervention Studies’ 42 (2015) 157–167. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Shelton, A. Kotsiou, M. D. Hetzel-Riggin, ‘Dig- ital Mental Health Interventions’, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Chen, S. Rodgers, Y. He, ‘A Critical Review of the E-Satisfaction Literature’ 52 (2008) 38–59. [CrossRef]

- C. Hollis, C. J. Falconer, J. L. Martin, C. Whitting- ton, S. Stockton, C. Glazebrook, E. B. Davies, ‘An- nual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems – a systematic and meta-review’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 58 (2017) 474– 503. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Hirschtritt, T. R. Insel, ‘Digital Technologies in Psychiatry: Present and Future’ 16 (2018) 251–258. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Calvo, K. Dinakar, R. Picard, P. Maes, ‘Com- puting in Mental Health’, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. N. Rudd, R. S. Beidas, ‘Digital Mental Health: The Answer to the Global Mental Health Crisis?’ 7 (2020) e18472. [CrossRef]

- J. Firth, J. Torous, J. Nicholas, R. Carney, A. Pratap, S. Rosenbaum, J. Sarris, ‘The efficacy of smartphone- based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials’, World Psychiatry 16 (2017) 287–298. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Naslund, K. A. Aschbrenner, L. A. Marsch, S. J. Bartels, ‘The future of mental health care: peer- to-peer support and social media’, Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 25 (2016) 113–122. [CrossRef]

- J. Proudfoot, B. Klein, A. Barak, P. Carlbring, P. Cuijpers, A. Lange, . . Ritterband, L, ‘Establish- ing guidelines for executing and reporting internet in- tervention research’, Cognitive behaviour therapy 40 (2011) 82–97. [CrossRef]

- B. Spadaro, N. A. Martin-Key, S. Bahn, ‘Building the Digital Mental Health Ecosystem: Opportunities and Challenges for Mobile Health Innovators’ 23 (2021) e27507. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Lisanby, ‘4. Transforming Mental Health Treat- ment Through Innovation in Tools, Targets, and Tri- als’ (2017). [CrossRef]

- S. Lal, ‘E-mental health: Promising advancements in policy, research, and practice’ 32 (2019) 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, M. Janssen, R. Wang, Y. Liu, ‘It Is Me, Chat- bot: Working to Address the COVID-19 Outbreak- Related Mental Health Issues in China. User Expe- rience, Satisfaction, and Influencing Factors’, Inter- national Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 38 (2022) 1182–1194. [CrossRef]

- M. Hassenzahl, ‘User Experience (UX): Towards an Experiential Perspective on Product Quality’, in: Proceedings of the 20th Conference on l’Interaction Homme-Machine, Association for Computing Ma- chinery, 2008, pp. 11–15. [CrossRef]

- F. Tosi, ‘From User-Centred Design to Human- Centred Design and the User Experience’, in: F. Tosi (Ed.), Design for Ergonomics, Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 47–59. [CrossRef]

- ‘D. A. Norman’, 2013.

- M. Hassenzahl, ‘User experience (UX): Towards an experiential perspective on product quality’, Proceed- ings of the 20th conference on l’Interaction Homme- Machine (2008) 11–15. [CrossRef]

- M. Lalmas, H. L. OB´rien, E. Yom-Tov, ‘Measuring User Engagement’, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Minge, M. Thüring, I. Wagner, C. V. Kuhr, ‘The meCUE Questionnaire: A Modular Tool for Measur- ing User Experience’, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Orlowski, B. Matthews, N. Bidargaddi, G. Jones, S. Lawn, A. Venning, P. Collin, ‘Mental Health Tech- nologies: Designing With Consumers’ 3 (2016) e4. [CrossRef]

- A. Sutcliffe, S. Thew, O. D. Bruijn, I. Buchan, P. Jarvis, J. McNaught, R. Procter, ‘User engage-ment by user-centred design in e-Health’ 368 (2010) 4209–4224. [CrossRef]

- D. Z. Q. Gan, L. McGillivray, M. E. Larsen, T. Bloomfield, M. Torok, ‘Promoting Engagement With Smartphone Apps for Suicidal Ideation in Young People: Development of an Adjunctive Strat- egy Using a Lived Experience Participatory Design Approach’ 7 (2023) e45234. [CrossRef]

- L. Menvielle, M. Ertz, J. François, A.-F. Audrain- Pontevia, ‘User-Involved Design of Digital Health Products’, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Mohr, M. N. Burns, S. M. Schueller, G. Clarke, M. Klinkman, ‘Behavioral Intervention Technologies: Evidence review and recommendations for future re- search in mental health’, General Hospital Psychiatry 35 (2013) 332–338. [CrossRef]

- L. Yardley, L. Morrison, K. Bradbury, I. Muller, ‘The Person-Based Approach to Intervention Devel- opment: Application to Digital Health-Related Be- havior Change Interventions’, J Med Internet Res 17 (2015) e30. [CrossRef]

- A. Baumel, J. M. Kane, ‘Examining predictors of real-world user engagement with self-guided eHealth interventions: analysis of mobile apps and websites using a novel dataset’, Journal of medical Internet research 18 (2016) 219–219. [CrossRef]

- S. Geiger, J. Steinbach, E.-M. Skoda, L. Jahre, Vanessa Rentrop, D. Kocol, C. Jansen, L. Schüren, M. Niedergethmann, M. Teufel, A. Bäuerle, ‘Needs and Demands for e-Mental Health Interventions in Individuals with Overweight and Obesity: User- Centred Design Approach’, Obesity Facts 16 (2022) 173–183. [CrossRef]

- P. Musiat, P. Goldstone, N. Tarrier, ‘Understanding the acceptability of e-mental health - attitudes and ex- pectations towards computerised self-help treatments for mental health problems’ 14 (2014) 109. [CrossRef]

- D. de Beurs, I. van Bruinessen, J. Noordman, R. Friele, S. van Dulmen, ‘Active Involvement of End Users When Developing Web-Based Mental Health Interventions’ 8 (2017). [CrossRef]

- A. S. Neilsen, R. L. Wilson, ‘Combining e-mental health intervention development with human com- puter interaction (HCI) design to enhance technology- facilitated recovery for people with depression and/or anxiety conditions: An integrative literature review’ 28 (2019) 22–39. [CrossRef]

- danah m. boyd, N. B. Ellison, ‘Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship’ 13 (2007) 210– 230. [CrossRef]

- C. Berryman, C. J. Ferguson, C. Negy, ‘Social Media Use and Mental Health among Young Adults’, Psy- chiatric Quarterly 89 (2018) 307–314. [CrossRef]

- L. yi Lin, J. E. Sidani, A. Shensa, A. Radovic, E. Miller, J. B. Colditz, B. L. Hoffman, L. M. Giles, B. A. Primack, ‘ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SO-CIAL MEDIA USE AND DEPRESSION AMONG U.S. YOUNG ADULTS’ 33 (2016) 323–331. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Naslund, A. Bondre, J. Torous, K. A. As- chbrenner, ‘Social Media and Mental Health: Bene- fits, Risks, and Opportunities for Research and Prac- tice’, Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science 5 (2020) 245–257. [CrossRef]

- P. Vornholt, M. De Choudhury, ‘Understanding the Role of Social Media–Based Mental Health Support Among College Students: Survey and Semistructured Interviews’, JMIR Ment Health 8 (2021) e24512. [CrossRef]

- K. Whitenton, ‘Minimise Cognitive Load to Maximise Usability’, 2013.

- A. Vermeeren, L.-C. Law, V. Roto, M. Obrist, J. Hoonhout, K. Väänänen, User experience evalu- ation methods: Current state and development needs, 2010. [CrossRef]

- C. Rohrer, ‘When to Use Which User-Experience Re- search Methods’, 2022.

- M. Obrist, V. Roto, A. Vermeeren, K. Väänänen- Vainio-Mattila, E. L.-C. Law, K. Kuutti, ‘In Search of Theoretical Foundations for UX Research and Prac- tice’, 2012. [CrossRef]

- T. Robertson, J. Simonsen, ‘Challenges and Opportu- nities in Contemporary Participatory Design’ (2012). [CrossRef]

- T. Binder, E. Brandt, J. Gregory, ‘Design participation(-s)’ 4 (2008) 1–3. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Smith, C. Bossen, A. M. Kanstrup, ‘Partic- ipatory design in an era of participation’ 13 (2017) 65–69. [CrossRef]

- C. Effendy, S. E. P. M. Margaret, A. Probandari, ‘The Utility of Participatory Action Research in the Nurs- ing Field: A Scoping Review’, Creative Nursing 28 (2022) 54–60. [CrossRef]

- S. Merritt, E. Stolterman, ‘Cultural Hybridity in Par- ticipatory Design’, in: Proceedings of the 12th Par- ticipatory Design Conference: Exploratory Papers, Workshop Descriptions, Industry Cases - Volume 2, Association for Computing Machinery, 2012, pp. 73– 76. [CrossRef]

- C. Spinuzzi, ‘The Methodology of Participatory De- sign’, Technical Communication 52 (2005) 163–174.

- M. Tremblay, C. Hamel, A. Viau-Guay, D. Giroux, ‘User Experience of the Co-design Research Approach in eHealth: Activity Analysis With the Course-of- Action Framework’ 9 (2022) e35577. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Sarmiento-Pelayo, ‘Co-design: A central ap- proach to the inclusion of people with disabilities’ 63 (2015) 149–154. [CrossRef]

- F. Barcellini, L. Prost, M. Cerf, ‘Designers’ and users’ roles in participatory design: What is actually co- designed by participants?’, Applied Ergonomics 50 (2015) 31–40. [CrossRef]

- M. Steen, M. Manschot, N. Koning, ‘Benefits of Co-design in Service Design Projects’, International Journal of Design 5 (2011).

- E. L.-C. Law, V. Roto, M. Hassenzahl, A. P. O. S. Vermeeren, J. Kort, ‘Understanding, Scoping and Defining User Experience: A Survey Approach’, in: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Association for Com- puting Machinery, 2009, pp. 719–728. [CrossRef]

- M. Hassenzahl, ‘Experience design: Technology for all the right reasons’, Synthesis Lectures on Human- Centred Informatics 3 (2010) 1–95. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Joseph, H. G. James, The experience economy (Updated ed.), Harvard Business Review Press, 2011.

- P. Desmet, P. Hekkert, ‘Framework of product ex- perience’, International Journal of Design 1 (2007) 57–66.

- J. Kort, A. P. O. S. Vermeeren, J. E. Fokker, ‘Concep- tualizing and measuring user experience’, in: E. Law, A. P. O. S. Vermeeren, M. Hassenzahl, M. Blythe (Eds.), Proceedings of the COST294-MAUSE Affili- ated Workshop: Toward a UX Manifesto.

- J. G. Jesse, The elements of user experience: user- centred design for the Web and beyond, volume 10, 2010.

- J. H. Gilmore, J. Pine, ‘Welcome to the experience economy.’, Harvard business review 76 4 (1998) 97– 105.

- E. L.-C. Law, P. van Schaik, V. Roto, ‘Attitudes to- wards user experience (UX) measurement’, Interna- tional Journal of Human-Computer Studies 72 (2014) 526–541. [CrossRef]

- D. Sward, G. Macarthur, ‘Making user experience a business strategy’, in: E. Law, A. Vermeeren, M. Hassenzahl, M. Blythe (Eds.), Proceedings of the COST294-MAUSE Affiliated Workshop: Toward a UX Manifesto, pp. 35–42.

- S. Mahlke, ‘Understanding users’ experience of in- teraction’, in: Proceedings of the Annual Conference on European Association of Cognitive Ergonomics - EACE’05 Chania, Association for Computing Ma- chinery, 2005, pp. 251–254.

- L. Feng, W. Wei, ‘An Empirical Study on User Ex- perience Evaluation and Identification of Critical UX Issues’, Sustainability 11 (2019). [CrossRef]

- L. Luther, V. Tiberius, A. Brem, ‘User Experience (UX) in Business, Management, and Psychology: A Bibliometric Mapping of the Current State of Re- search’ 4 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Hu, X. Huang, ‘Based on the Experience of Product Interaction Design’, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Figma, ‘Figma Collaborative Interface Design Soft- ware Tool’, 2023.

- D. Norman, The invisible computer: Why good prod- ucts can fail, the personal computer is so complex, and information appliances are the solution, The MIT Press, 1998.

- F. Kensing, J. Blomberg, ‘Participatory Design: Is- sues and Concerns’, Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 7 (1998) 167–185. [CrossRef]

- G. Doherty, D. Coyle, M. Matthews, ‘Design and eval- uation guidelines for mental health technologies’, In- teracting with Computers 22 (2010) 243–252. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Johnson, A. M. Bisantz, A. L. Reynolds, S. T. Meier, ‘Mobile Mental Health Technologies: Unique Challenges and Solutions for an effective User Cen- tered Design Methodology’, Proceedings of the Hu- man Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 63 (2019) 1908–1909. [CrossRef]

- J. Dirmaier, S. Liebherz, S. Sänger, M. Härter, L. Tlach, ‘Psychenet.de: Development and process evaluation of an e-mental health portal’, Informatics for Health and Social Care 41 (2016) 267–285. [CrossRef]

- A. Buchner, E. Erdfelder, F. Faul, A.-G. Lang, ‘G*Power Statistical Power Analysis Tool’, 2023.

- S. H. Henni, S. Maurud, K. S. Fuglerud, A. Moen, ‘The experiences, needs and barriers of people with impairments related to usability and accessibility of digital health solutions, levels of involvement in the design process and strategies for participatory and universal design: a scoping review’, BMC Public Health 22 (2022) 35. [CrossRef]

- D. Zarnowiecki, C. E. Mauch, G. Middleton, L. Matwiejczyk, W. L. Watson, J. Dibbs, A. Dessaix, R. K. Golley, ‘A systematic evaluation of digital nutri- tion promotion websites and apps for supporting par- ents to influence children’s nutrition’, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activ- ity 17 (2020) 17. [CrossRef]

- A. S. Islind, T. Lindroth, J. Lundin, G. Steineck, ‘Co- designing a digital platform with boundary objects: bringing together heterogeneous users in healthcare’, Health and Technology 9 (2019) 425–438. [CrossRef]

- O. Olusanya, W. G. Collier, S. Marshall, V. Knapp, A. Baldwin, ‘Enhancing digitally-mediated human- centred design with digitally-mediated community based participatory research approaches for the de- velopment of a digital access-to-justice platform for military veterans and their families’, Journal of Par- ticipatory Research Methods 3 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. I. Shire, G. T. Jun, S. Robinson, ‘Healthcare work- ers’ perspectives on participatory system dynamics modelling and simulation: designing safe and effi- cient hospital pharmacy dispensing systems together’ 63 (2020) 1044–1056. [CrossRef]

- M. Ferati, A. Babar, K. Carine, A. Hamidi, C. Mört- berg, ‘Participatory Design Approach to Internet of Things: Co-designing a Smart Shower for and with People with Disabilities’, in: M. Antona, C. Stephanidis (Eds.), Universal Access in Human- Computer Interaction. Virtual, Augmented, and In- telligent Environments, Springer International Pub- lishing, 2018, pp. 246–261. [CrossRef]

- S. Michie, L. Yardley, R. West, K. Patrick, F. Greaves, ‘Developing and Evaluating Digital In-terventions to Promote Behavior Change in Health and Health Care: Recommendations Resulting From an International Workshop’, J Med Internet Res 19 (2017) e232. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen, L. Peng, B. Jing, C. Wu, J. Yang, G. Cong, ‘The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on User Ex- perience with Online Education Platforms in China’, Sustainability 12 (2020). [CrossRef]

- S. Donetto, P. Pierri, V. Tsianakas, G. Robert, ‘Experience-based Co-design and Healthcare Im- provement: Realizing Participatory Design in the Public Sector’, The Design Journal 18 (2015) 227– 248. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Henni, S. Maurud, K. S. Fuglerud, A. Moen, ‘The experiences, needs and barriers of people with impairments related to usability and accessibility of digital health solutions, levels of involvement in the design process and strategies for participatory and universal design: a scoping review’, BMC Public Health 22 (2022) 35. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, Q. Wang, T. Roh, ‘Do information and ser- vice quality affect perceived privacy protection, satis- faction, and loyalty? Evidence from a Chinese O2O- based mobile shopping application’, Telematics and Informatics 56 (2021) 101483. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).