Submitted:

17 March 2024

Posted:

18 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Grape

2.2. Standards and Chemicals

2.3. Winemaking

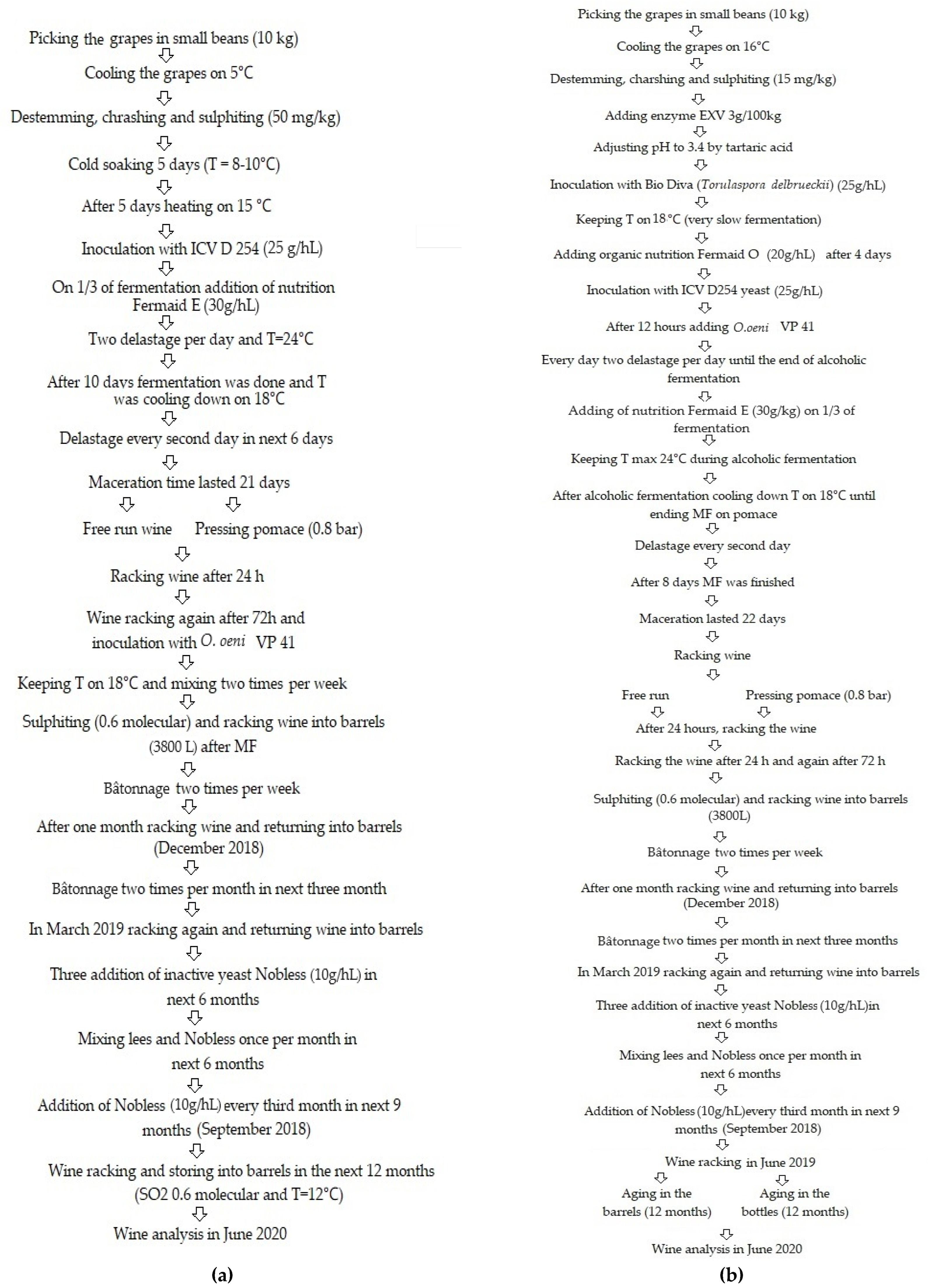

2.3.1. Traditional Processing

2.3.2. Innovative Processing

2.4. HPLC Anaysis

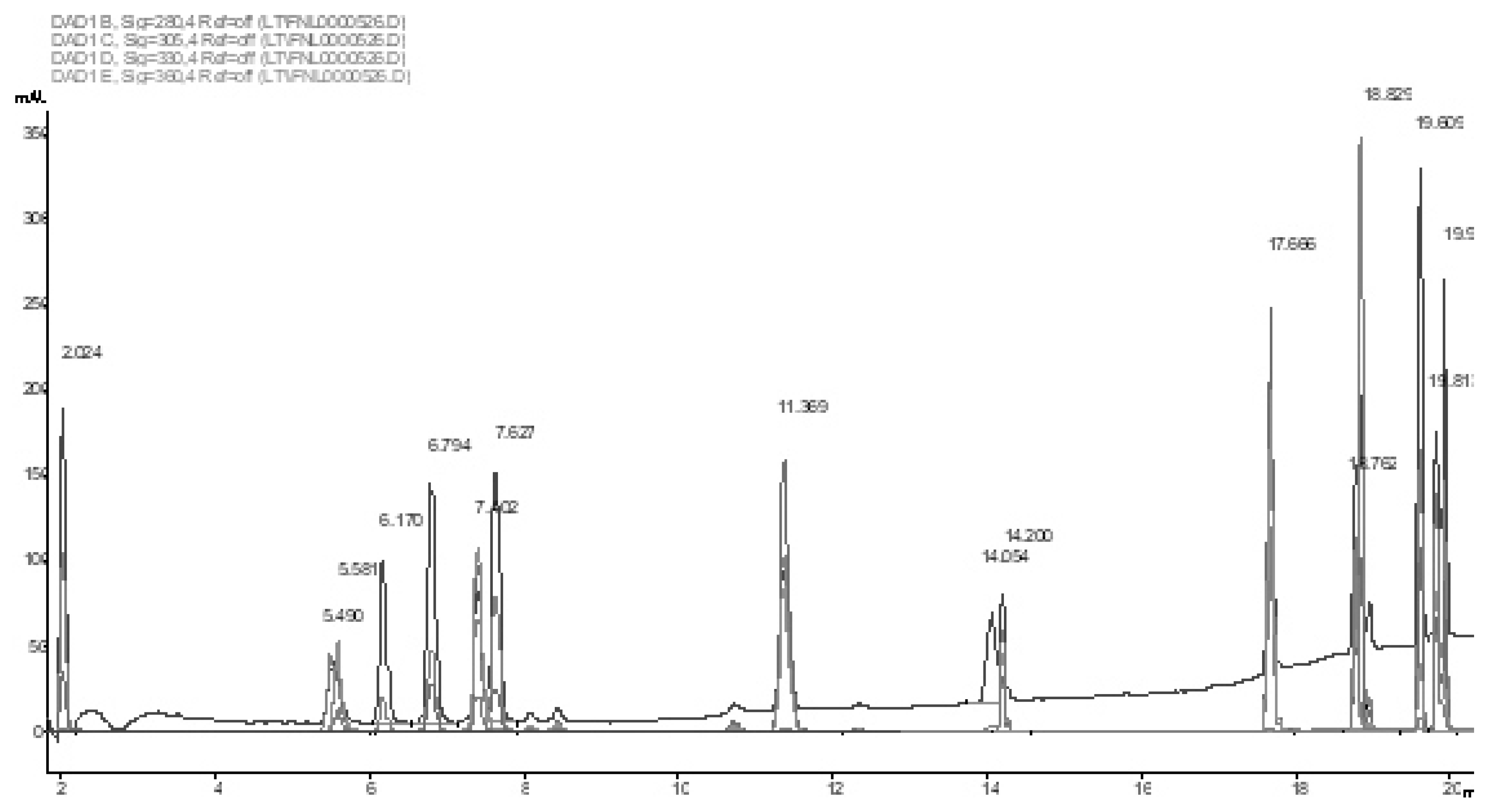

2.4.1. Phenols

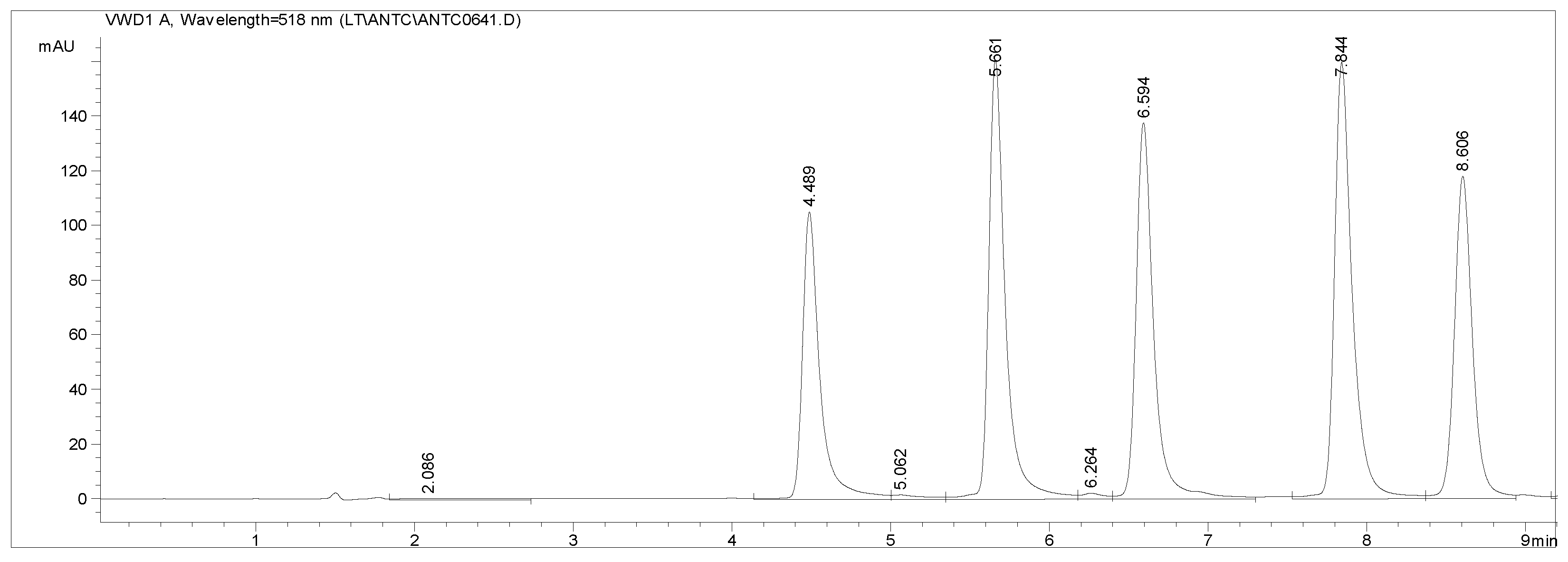

2.4.2. Anthocyanins

2.5. Determination of Titratable Acidity in Must

2.6. Determination of the Sugar Content in Must

2.7. Determination of Physico-Chemical Parameters in Wine

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Stilbenes

3.2. Quercetin

3.3. Biologically Active Phenols

3.4. Phenolic Acids

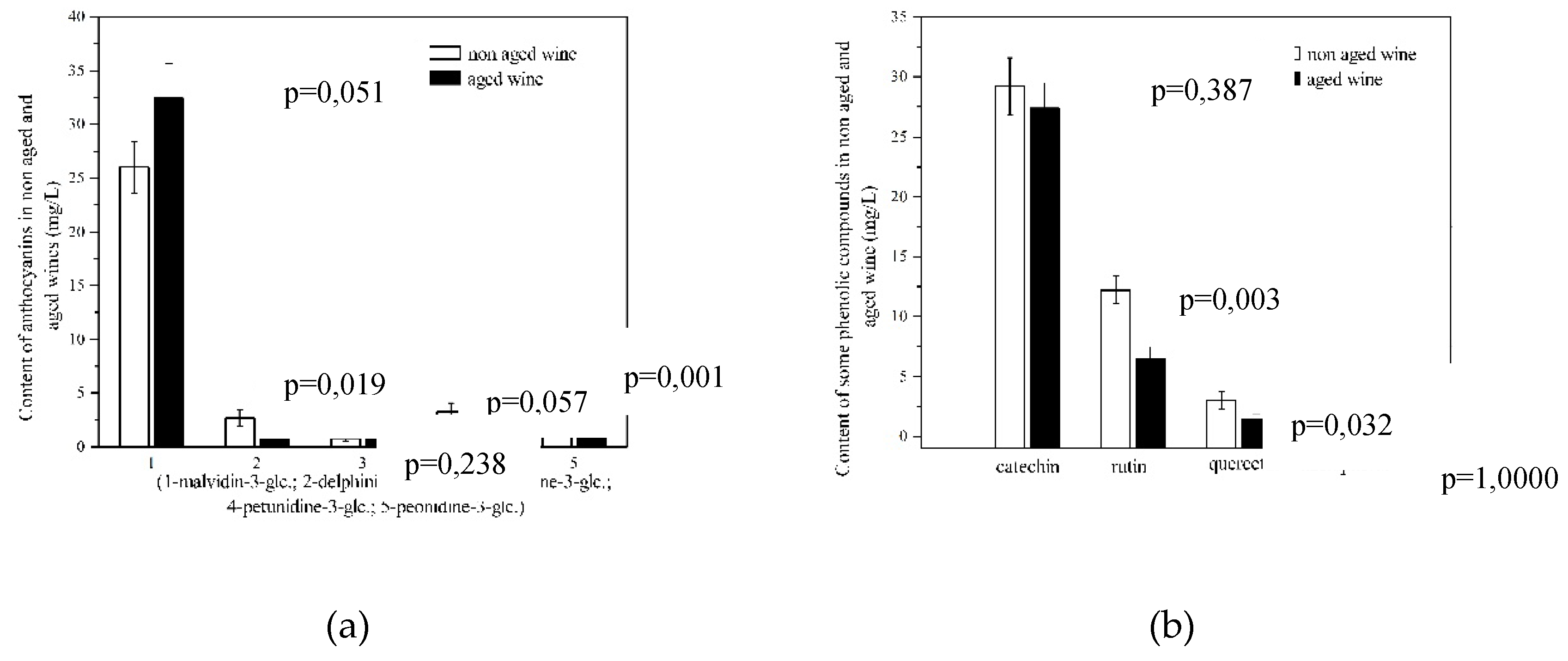

3.5. Anthocyanins

3.6. Complete Physico-Chemical and Sensory Analysis of the Wine

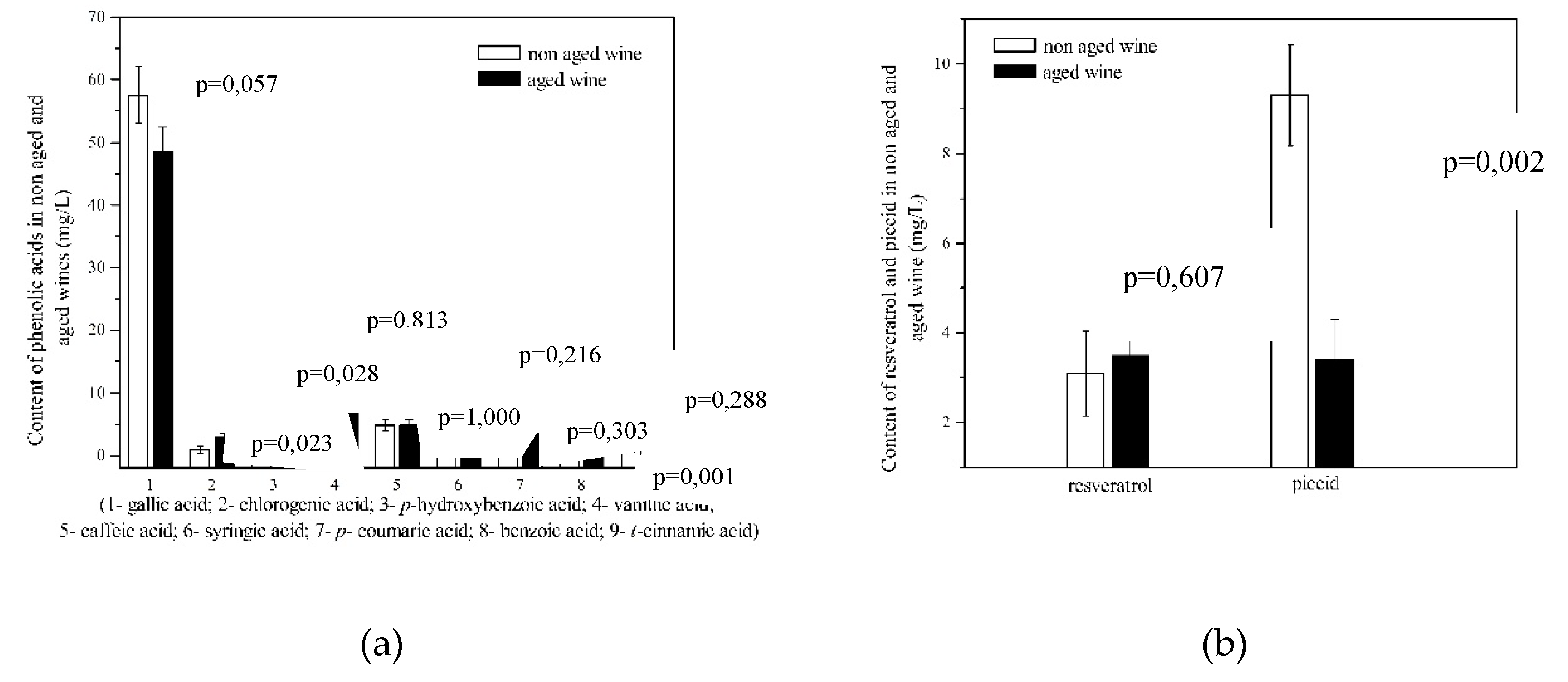

3.7. Wine after Storage

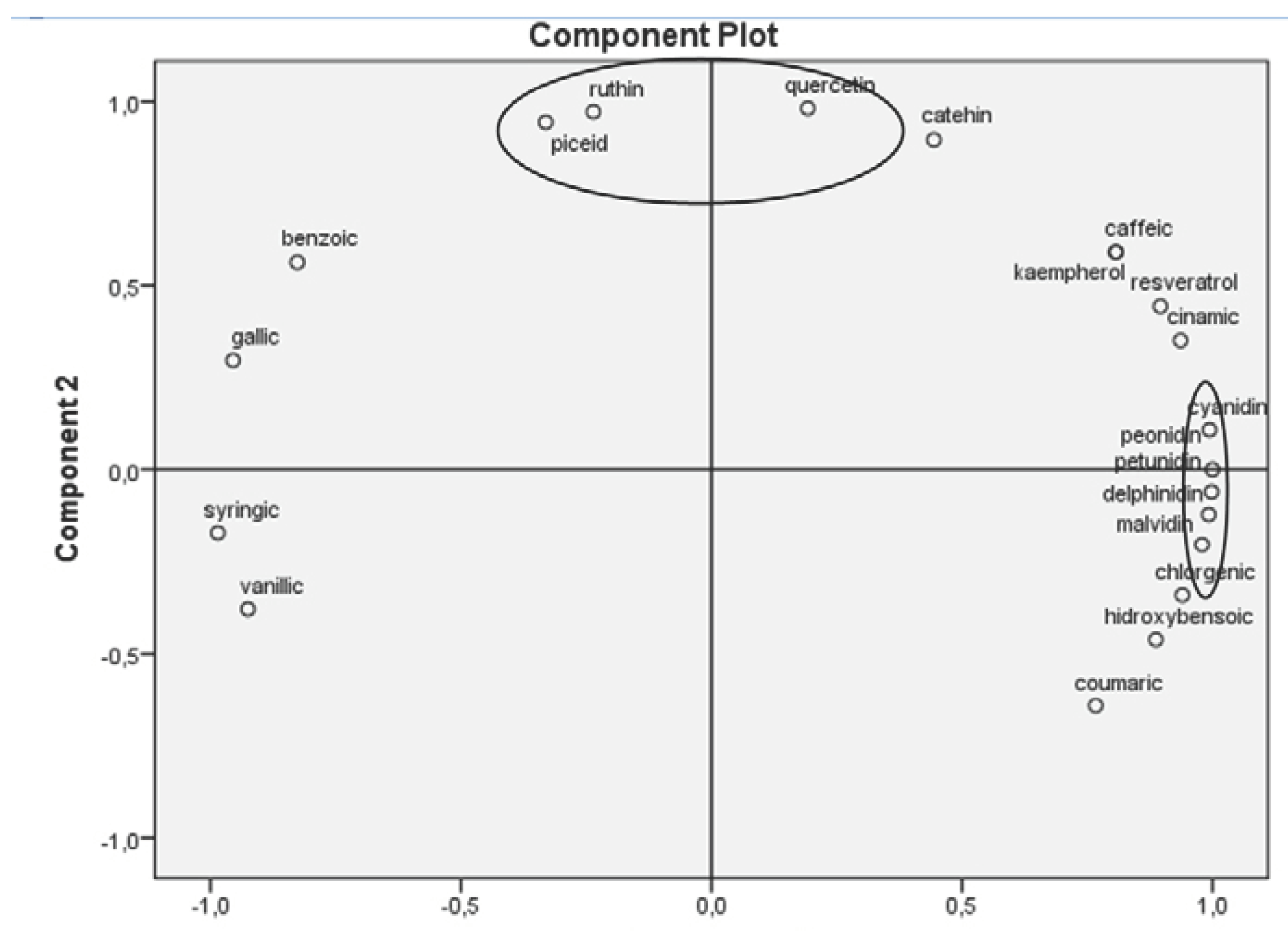

Principal Component Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langcake, P.; Pryce, R. J. The production of resveratrol by Vitis vinifera and other members of the Vitaceae as a response to infection or injury. Physiol. Plant Pathol. 1976, 9, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téguo, P.; Hawthorne, M. E.; Cuendet, M.; Mérillon, J. M.; Kinghorn, A. D.; Pezzuto, J. M.; Mehta, R. G. Potential cancer-chemopreventive activities of wine stilbenoids and flavans extracted from grape (Vitis vinifera) cell cultures. Nutr. Cancer. 2001, 40, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balga, I.; Lesko, A.; Ladanyi, M.; Kallay, M. Influence of ageing on changes in polyphenolic compounds in red wines. Czech J. Food Sci. 2015, 32, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvejić, J. M.; Djekic, S. V.; Petrovic, A. V.; Atanackovic, M. T.; Jovic, S. M.; Brceski, I. D.; Gojkovic-Bukarica, L. C. Determination of trans-and cis-resveratrol in Serbian commercial wines. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2010, 48, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanacković, M.; Petrović, A.; Jović, S.; Gojković-Bukarica, L.; Bursać, M.; Cvejić, J. Influence of winemaking techniques on the resveratrol content, total phenolic content and antioxidant potential of red wines. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, J.; Han, C.; Yang, J.; Chaudhry, M. T.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Yin, Y. Quercetin, inflammation and immunity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantos, E.; Espín, J. C.; Fernández, M. J.; Oliva, J.; Tomás-Barberán, F. A. Postharvest UV-C-irradiated grapes as a potential source for producing stilbene-enriched red wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Ma, W.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, G.; Fang, Z. Wine phenolic profile altered by yeast: Mechanisms and influences. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf., 2021, 20, 3579–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tristezza, M.; di Feo, L.; Tufariello, M.; Grieco, F.; Capozzi, V.; Spano, G.; Mita, G. Simultaneous inoculation of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria: Effects on fermentation dynamics and chemical composition of Negroamaro wine. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaar, P. P.; Du Plessis, H. W.; Jolly, N. P.; Van Der Rijst, M.; Du Toit, M. Non-Saccharomyces yeast and lactic acid bacteria in Co-inoculated fermentations with two Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast strains: A strategy to improve the phenolic content of Syrah wine. Food Chem. 2019, 4, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngqumba, Z.; Ntushelo, N.; Jolly, N. P.; Ximba, B. J.; Minnaar, P. P. Effect of Torulaspora delbrueckii yeast treatment on flavanols and phenolic acids of Chenin blanc wines. S. Afr. J. Enol. 2017, 38, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morata, A.; Escott, C.; Loira, I.; Del Fresno, J. M.; González, C.; Suárez-Lepe, J. A. Influence of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts in the formation of pyranoanthocyanins and polymeric pigments during red wine making. Molecules 2019, 24, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, M.; Velázquez, R. The yeast Torulaspora delbrueckii: An interesting but difficult-to-use tool for winemaking. Fermentation 2018, 4, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, I.; Navascués, E.; Marquina, D.; Santos, A.; Calderon, F.; Benito, S. Dynamic analysis of physiological properties of Torulaspora delbrueckii in wine fermentations and its incidence on wine quality. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escribano-Viana, R.; Portu, J.; Garijo, P.; López, R.; Santamaría, P.; López-Alfaro, I.; Gutiérrez, A. R.; González-Arenzana, L. Effect of the sequential inoculation of non-Saccharomyces/Saccharomyces on the anthocyans and stilbenes composition of tempranillo wines. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Escott, C.; Loira, I.; Del Fresno, J. M.; Morata, A.; Tesfaye, W.; Calderon, F.; Suárez-Lepe, J. A.; Han. S.; Benito, S. Use of non-Saccharomyces yeasts and oenological tannin in red winemaking: Influence on colour, aroma and sensorial properties of young wines. Food Microbiol. 2018, 69, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnaar, P. P.; Ntushelo, N.; Ngqumba, Z.; Van Breda, V.; Jolly, N. P. Effect of Torulaspora delbrueckii yeast on the anthocyanin and flavanol concentrations of Cabernet franc and Pinotage wines. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 36, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkić, T. M.; Torović, L. D.; Lesjak, M. M.; Četojević-Simin, D. D.; Beara, I. N. Activity profiling of Serbian and some other European Merlot wines in inflammation and oxidation processes. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanacković Krstonošić, M.; Cvejić Hogervorst, J.; Mikulić, M.; Gojković Bukarica, Lj. Development of HPLC method for detemination of phenolic compounds on a core shell column by direct injection of wine samples. Acta Chromatogr. 2020, 32, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, H.; Brunner, H.R. Gentranke-Analytik; Verlag Heller-Chemie und Verwaltunsgesellschaft mbH: Darmstadt, Germany, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Compendium Methods of Analysis of Wine and Musts Vol1 and Vol2. URL: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/publication/2022-10/Compendium%20Methods%20of%20Analysis%20of%20Wine%20and%20Musts%20Vol1%20and%20Vol2.pdf (accessed on 10. 06. 2021).

- Kostadinović, S.; Wilkens, A.; Stefova, M.; Ivanova, V.; Vojnoski, B.; Mirhosseini, H.; Winterhalter, P. Stilbene levels and antioxidant activity of Vranec and Merlot wines from Macedonia: Effect of variety and enological practices. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 3003–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaensly, F.; Agustini, B. C.; da Silva, G. A.; Picheth, G.; Bonfim, T. M. B. Autochthonous yeasts with β-glucosidase activity increase resveratrol concentration during the alcoholic fermentation of Vitis labrusca grape must. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, T.; Estrella, I.; Pérez-Gordo, M.; Alegría, E. G.; Tenorio, C.; Ruiz-Larrrea, F.; Moreno-Arribas, M. V. Contribution of malolactic fermentation by Oenococcus oeni and Lactobacillus plantarum to the changes in the nonanthocyanin polyphenolic composition of red wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 5260–5266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poussier, M.; Guilloux-Benatier, M.; Torres, M.; Heras, E.; Adrian, M. Influence of different maceration techniques and microbial enzymatic activities on wine stilbene content. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2003, 54, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tıraş, Z. S. E.; Okur, H. H.; Günay, Z.; Yıldırım, H. K. Different approaches to enhance resveratrol content in wine. Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 2022, 37, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Okuda, T.; Yokotsuka, K. Contents of resveratrol, piceid, and their isomers in commercially available wines made from grapes cultivated in Japan. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997, 61, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerogiannaki-Christopoulou, M.; Athanasopoulos, P.; Kyriakidis, N.; Gerogiannaki, I. A.; Spanos, M. trans-Resveratrol in wines from the major Greek red and white grape varieties. Food Control 2006, 17, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabey, N.; Yilmaztekin, M.; Hayaloglu, A. A. Effect of maceration duration on physicochemical characteristics, organic acid, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of red wine from Vitis vinifera L. Karaoglan. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3557–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Generalić Mekinić, I.; Skračić, Ž.; Kokeza, A.; Soldo, B.; Ljubenkov, I.; Banović, M.; Skroza, D. Effect of winemaking on phenolic profile, colour components and antioxidants in Crljenak kaštelanski (sin. Zinfandel, Primitivo, Tribidrag) wine. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1841–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alencar, N. M. M.; Cazarin, C. B. B.; Corrêa, L. C.; Maróstica Junior, M. R.; Biasoto, A. C. T.; Behrens, J. H. Influence of maceration time on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of the Syrah must and wine. J. Food Biochem. 2017, 42, e12471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginjom, I.; D’Arcy, B.; Caffin, N.; Gidley, M. Phenolic compound profiles in selected Queensland red wines at all stages of the wine-making process. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Strollo, D.; Ugliano, M.; Lecce, L.; Moio, L. trans-Resveratrol, quercetin, (+)-catechin, and (−)-epicatechin content in south Italian monovarietal wines: relationship with maceration time and marc pressing during winemaking. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5747–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careri, M.; Corradini, C.; Elviri, L.; Nicoletti, I.; Zagnoni, I. Direct HPLC analysis of quercetin and trans-resveratrol in red wine, grape, and winemaking by products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5226–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisov, N.; Petrović, A.; Čakar, U.; Jadranin, M.; Tešević, V.; Bukarica-Gojković, L. Extraction kinetic of some phenolic compounds during Cabernet Sauvignon alcoholic fermentation and antioxidant properties of derived wines. Maced. J. Chem. Chem. 2020, 39, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, B. C.; Radovanović, A. N.; Souquet, J. M. Phenolic profile and free radical-scavenging activity of Cabernet Sauvignon wines of different geographical origins from the Balkan region. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 90, 2455–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Anu-Appaiah, K. A.; Lin, T. F. Timing of inoculation of Oenococcus oeni and Lactobacillus plantarum in mixed malo-lactic culture along with compatible native yeast influences the polyphenolic, volatile and sensory profile of the Shiraz wines. LWT 2022, 158, 113130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Ortín, A. B.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; Ros-García, J. M.; López-Roca, J. M.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Improving colour extraction and stability in red wines: the use of maceration enzymes and enological tannins. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 40, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturano, Y. P.; Rodríguez Assaf, L. A.; M. Toro, E.; Nally, M. C.; Vallejo, M.; Castellanos de Figueroa,L. I.; Combina, M.; Vazquez, F. Multi-enzyme production by pure and mixed cultures of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts during wine fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 155, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artem, V.; Antoce, A. O.; Geana, E. I.; Ranca, A. Effect of grape yield and maceration time on phenolic composition of ‘Fetească neagră’organic wine. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2021, 49, 12345–12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E. Q.; Deng, G. F.; Guo, Y. J.; Li, H. B. Biological activities of polyphenols from grapes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 622–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heras-Roger, J.; Díaz-Romero, C.; Darias-Martín, J. A comprehensive study of red wine properties according to variety. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto Vázquez, E.; Río Segade, S.; Orriols Fernández, I. Effect of the winemaking technique on phenolic composition and chromatic characteristics in young red wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 231, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisov, N. Dynamics of biologically active phenolic compounds of Cabernet Sauvignon grape variety during phenophases of maturation, primary processing, vinification and influence on wine antioxidant capacity. Doctoral Thesis, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, J.; Borges, F. Wine and grape polyphenols—A chemical perspective. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1844–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T. R.; Osborne, J. P. Loss of Pinot noir wine color and polymeric pigment after malolactic fermentation and potential causes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2015, 66, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Arribas, V.; Polo, C. Wine Chemistry and Biochemistry, 1st ed; Springer: New York, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, I.; Aleixandre, J. L.; García, M. J.; Lizama, V. Impact of prefermentative maceration on the phenolic and volatile compounds in Monastrell red wines. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2006, 563, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lamela, C.; García-Falcón, M. S.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Orriols-Fernández, I. Influence of grape variety, vine system and enological treatments on the colour stability of young red wines. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, V.; Vojnoski, B.; Stefova, M. Effect of winemaking treatment and wine aging on phenolic content in Vranec wines. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Sánchez, J. X.; García-Falcón, M. S.; Garrido, J.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Martins-Dias, L. R.; Mejuto, X. C. Phenolic compounds and colour stability of Vinhao wines: Influence of wine-making protocol and fining agents. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Plaza, E.; Gil-Muñoz, R.; López-Roca, J. M.; Martı́nez-Cutillas, A.; Fernández-Fernández, J. I. Maintenance of colour composition of a red wine during storage. Influence of prefermentative practices, maceration time and storage. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2002, 35, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimpilas, A.; Panagopoulou, M.; Tsimogiannis, D.; Oreopoulou, V. Anthocyanin copigmentation and color of wine: The effect of naturally obtained hydroxycinnamic acids as cofactors. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carew, A. L.; Smith, P.; Close, D. C.; Curtin, C.; Dambergs, R. G. Yeast effects on Pinot noir wine phenolics, color, and tannin composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 9892–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, A.; Serratosa, M. P.; Merida, J. Influence of bottle storage time on colour, phenolic composition and sensory properties of sweet red wines. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimpilas, A.; Tsimogiannis, D.; Balta-Brouma, K.; Lymperopoulou, T.; Oreopoulou, V. Evolution of phenolic compounds and metal content of wine during alcoholic fermentation and storage. Food Chem. 2015, 178, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellari, M.; Matricardi, L.; Arfelli, G.; Galassi, S.; Amati, A. Level of single bioactive phenolics in red wine as a function of the oxygen supplied during storage. Food Chem. 2000, 69, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprun, A. R.; Dubrovina, A. S.; Tyunin, A. P.; Kiselev, K. V. Profile of stilbenes and other phenolics in Fanagoria white and red Russian wines. Metabolites 2021, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Falcón, M. S.; Pérez-Lamela, C.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Simal-Gándara, J. Determination of phenolic compounds in wines: Influence of bottle storage of young red wines on their evolution. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiker, M.; Anderson, S.; Johnson, J. B.; Mani, J. S.; Wakeling, L.; Bowry, V. Loss of trans-resveratrol during storage and ageing of red wines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2020, 26, 385–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wine | Traditional winemaking technology |

Innovative winemaking technology |

% increase in content |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trans-resveratrol (mg/L) | 1.30±0.09 | 3.10±0.10 | 138.5 | <0.001* |

| Piceid (mg/L) | 4.80±0.18 | 9.30±0.20 | 93.8 | <0.001* |

| Quercetin (mg/L) | 0.70±0.04 | 3.0±0.08 | 328.6 | <0.001* |

| Wine | Traditional winemaking technology |

Innovative winemaking technology |

% increase in content | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catechin (mg/L) | 25.3±0.90 | 29.2±1.10 | 15.4 | 0.009** |

| Rutin (mg/L) | 7.3±0.20 | 12.2±0.20 | 67.1 | <0.001** |

| Kaempherol (mg/L) | n.d.* | 0.40±0.04 | 100.0 |

| Phenolic acids (mg/L) | Traditional winemaking technology |

Innovative winemaking technology |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 58.90±1.60 | 57.60±1.20 | 0.323* |

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.80±0.05 | 0.95±0.09 | 0.065* |

| p-hidroxybenzoic acid | 0.70±0.04 | 0.60±0.02 | 0.018* |

| Vanillic acid | 10.40±0.25 | 9.50±0.40 | 0.030* |

| Caffeic acid | 3.70±0.20 | 4.80±0.25 | 0.004* |

| Syringic acid | 6.90±0.30 | 5.40±0.20 | 0.002* |

| p-coumaric acid | 3.0±0.12 | 2.80±0.15 | 0.146* |

| Benzoic acid | 2.50±0.10 | 3.0±0.10 | 0.004* |

| t-cinnamic acid | 0.10±0.02 | 0.75±0.04 | <0.001* |

| Anthocyanin (mg/L) | Traditional winemaking technology |

Innovative winemaking technology |

% increase in content |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| delphinidin 3-O-glucoside |

1.60±0.15 | 2.70±0.25 | 68.80 | 0.003* |

| cyanidin 3-O-glucoside |

0.40±0.04 | 0.80±0.10 | 100.0 | 0.003* |

| petunidin 3-O-glucoside |

2.0±0.05 | 3.30±0.15 | 65.0 | <0.001* |

| peonidin 3-O-glucoside |

2.0±0.05 | 3.80±0.25 | 90.0 | <0.001* |

| malvidin 3-O-glucoside |

24.20±0.80 | 26.0±0.95 | 7.40 | 0.066* |

| Wine | Traditional winemaking technology |

Innovative winemaking technology |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol content (vol%) | 13.7±0.2 | 13.9±0.1 |

| Sugar (g/L) | 0.75±0.2 | 0.62±0.2 |

| Total extract (g/L) | 23.6±0.2 | 25.2±0.2 |

| Extract without sugar (g/L) | 23.6±0.2 | 25.2±0.2 |

| Total acids as tartaric (g/L) | 4.69±0.2 | 4.75±0.3 |

| Volatile acids as acetic (g/L) | 0.45±0.3 | 0.62±0.2 |

| Total SO2 (mg/L) | 110.6±0.2 | 112.4±0.2 |

| Free SO2 (mg/L) | 27.4±0.2 | 29.3±0.2 |

| Ashes (g/L) | 2.8±0.2 | 2.4±0.3 |

| Total phenolic content as gallic (g/L) | 2.1±0.1 | 3.9±0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).