Submitted:

24 November 2023

Posted:

28 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Study Aim

- Type of video content (climate change or non-climate change).

- Time (pre or baseline and post-intervention).

- Positive and negative affect.

- Pro-environmental behavioural intentions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Measures

- Positive and Negative Affect (PANAS)

- Scale Adaptation - Pro-environmental Behaviour Intentions (PEBI)

2.3. Other Materials

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Scale Reliability

3.2. Baseline Demographics

3.3. Data Sets (1–3)

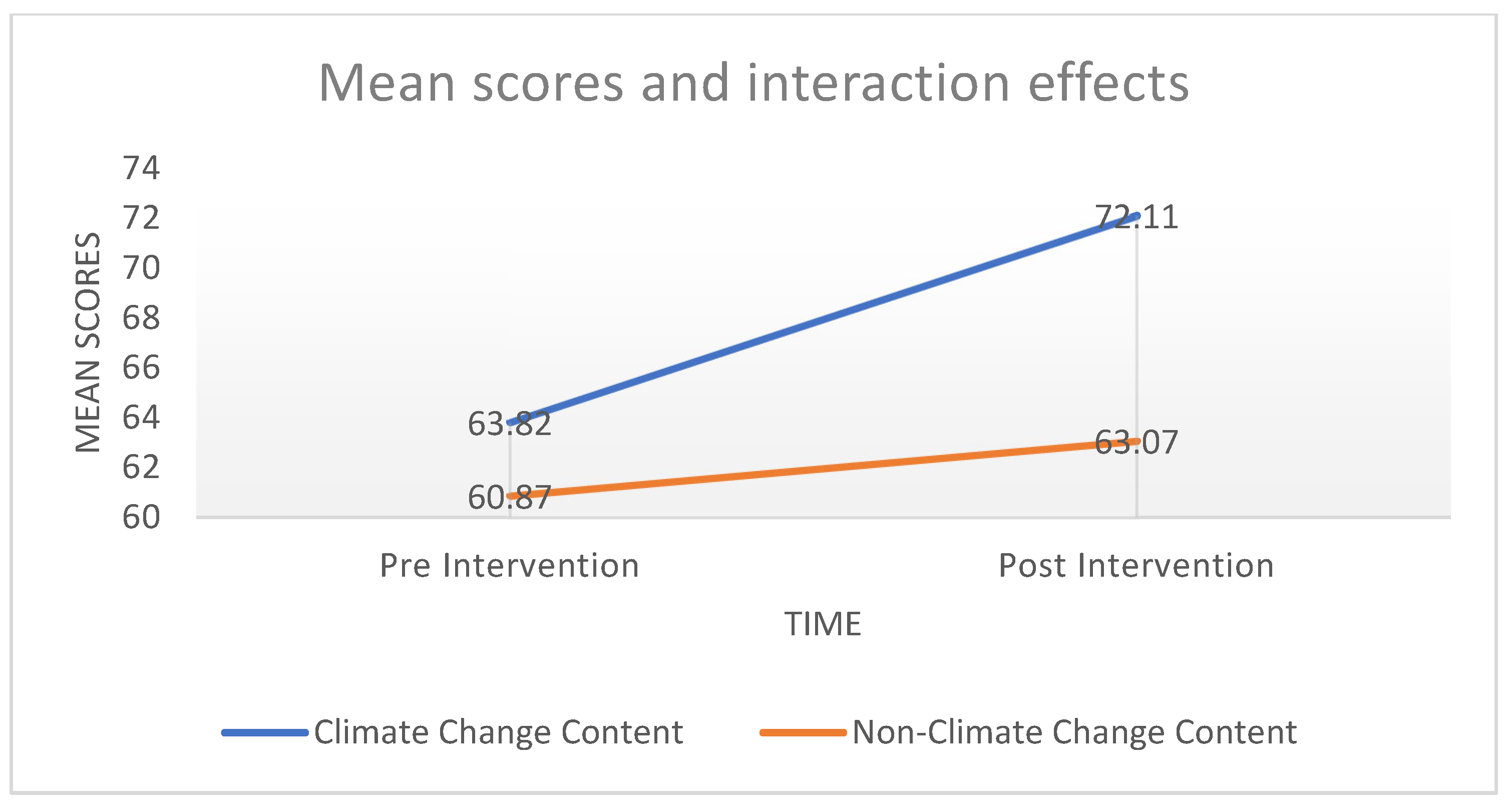

| Pro-environmental behavioural intention scores (pre) | Pro-environmental behavioural intention scores (post) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change content | 63.82 (9.42) | 72.11 (12.52) | 67.96 (11.79) |

| Non-climate change content | 60.87 (11.94) | 63.07 (12.76) | 61.97 (12.34) |

| Total | 62.35 (10.68) | 67.59 (12.64) |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Scale 1: Recurring Pro-environmental Behaviour Scale (adapted PEBI version)

- When you visit the grocery store, how often do you intend to use reusable bags?

- How often do you intend to walk, bicycle, carpool or take public transportation instead of driving a vehicle by yourself?

- How often do you intend to drive slower than 60mph on the highway?

- How often do you intend to go on personal travel (non-business) air travel?

- How often do you intend to compost your household food garbage?

- How often do you intend to eat meat?

- How often do you intend to eat dairy products such as milk, cheese, eggs, or yoghurt?

- How often do you intend to eat organic food?

- How often do you intend to eat local food?

- How often do you intend to eat a home vegetable garden (during the growing season)?

- How often do you intend to turn your personal electronics off or in low-power mode when not in use?

- When you buy light bulbs, how often do you intend to buy high-efficiency compact fluorescent (CFL) or LED bulbs?

- How often do you intend to act to conserve water, when showering, cleaning clothes, dishes, watering plants, or other uses?

- How often do you intend to use aerosol products?

- When you are in PUBLIC, how often do you intend to sort trash into recycling?

- When you are in PRIVATE, how often do you intend to sort trash into the recycling?

- How often do you intend to discuss environmental topics, either in person or with online posts (Facebook, Twitter, etc.)?

- When you buy clothing, how often do you intend it to be from environmentally friendly brands?

- How often do you intend to carry a reusable water bottle?

- How often do you intend to engage in political action or activism related to protecting the environment?

- How often do you intend to educate yourself about the environment?

References

- Spence, A., Pidgeon, N., & Uzzell, D. Climate change—Psychology’s contribution. Psychologist. 2009, 22, 108–111.

- Lawrance, D. E., Thompson, R., Fontana, G., & Jennings, D. N. The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional wellbeing: Current evidence and implications for policy and practice. 2021, 36, 36. [CrossRef]

- Wachholz, S., Artz, N., & Chene, D. Warming to the idea: University students’ knowledge and attitudes about climate change. Int Journal of Sustainability in Higher Ed. 2014, 15, 128–141. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on health, environment and climate change: the transformation needed to improve lives and wellbeing sustainably through healthy environments. 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2023, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331959/9789240000377-eng.pdf.

- Reser, J. P., & Swim, J. K. Adapting to and coping with the threat and impacts of climate change. American Psych. 2011, 66, 277–289. [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. W., & Joffe, H. Climate change in the British press: The role of the visual. Journal of Risk Research. 2009, 12, 647–663. [CrossRef]

- Barbett, L., Stupple, E., Sweet, M., Schofield, M., & Richardson, M. Measuring Actions for Nature—Development and Validation of a Pro-Nature Conservation Behaviour Scale. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 4885. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A. E. Psychometric Properties of the Climate Change Worry Scale. Int Journal of Environ Research and Pub Health. 2021, 18, 494. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, T. L., Stanley, S. K., O’Brien, L. V., Wilson, M. S., & Watsford, C. R. The Hogg Eco-Anxiety Scale: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. Global Environ Change. 2021, 71, 102391. [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ Ed Research. 2012, 18, 625–642. [CrossRef]

- Maran, D. A., & Begotti, T. Media Exposure to Climate Change, Anxiety, and Efficacy Beliefs in a Sample of Italian University Students. Int Journal of Environ Research and Pub Health 2021, 18, 9358. [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S., & Karazsia, B. T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. Journal of Environ Psych. 2020, 69, 101434. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Chronic environmental change: Emerging ‘psychoterratic’syndromes. Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities. Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 43–56. 2011, pp. 43–56.

- Innocenti, M., Santarelli, G., Lombardi, G. S., Ciabini, L., Zjalic, D., Di Russo, M., & Cadeddu, C. How Can Climate Change Anxiety Induce Both Pro-Environmental Behaviours and Eco-Paralysis? The Mediating Role of General Self-Efficacy. Int Journal of Environ Research and Pub Health. 2023, 20, Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Reser, J. P., Bradley, G. L., Glendon, A. I., Ellul, M. C., & Callaghan, R. Public risk perceptions, understandings and responses to climate change and natural disasters in Australia, 2010 and 2011. 2012. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility Gold Coast. 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2023, from https://www.unisdr.org/preventionweb/files/30470_finalreportreserpublicriskperceptio.pdf.

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Dis. 2020, 74, 102263. [CrossRef]

- Arlt, D., Hoppe, I., & Wolling, J. Climate change and media usage: Effects on problem awareness and behavioural intentions. Int Comm Gazette. 2011, 73, 45–63. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F. G., Wölfing, S., & Fuhrer, U. Environmental attitude and ecological behaviour. Journal of environ psych. 1999, 19, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A., & Preisendörfer, P. Environmental behavior: Discrepancies between aspirations and reality. Rationality and Soc. 1998, 10, 79–102. [CrossRef]

- Romeu, D. Is climate change a mental health crisis? BJPsych Bulletin. 2021, 45, 243–245. [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C. A., Doran, R., Hanss, D., Ojala, M., Salmela-Aro, K., van den Broek, K. L., Bhullar, N., Aquino, S. D., Marot, T., Schermer, J. A., Wlodarczyk, A., Lu, S., Jiang, F., Maran, D. A., Yadav, R., Ardi, R., Chegeni, R., Ghanbarian, E., Zand, S., … Karasu, M. Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: Correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. Journal of Environ Psych. 2022, 84, 101887. [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. Learning from a social cognitive theory perspective. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed.; R. J. Tierney, F. Rizvi, & K. Ercikan Eds., Elsevier, Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 22–35. [CrossRef]

- Brulle, R. J., Carmichael, J., & Jenkins, J. C. Shifting public opinion on climate change: An empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010. Climatic Change. 2012, 114, 169–188. [CrossRef]

- Harth, N. S. Affect, (group-based) emotions, and climate change action. Current Opinion in Psych. 2021, 42, 140–144. [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. Environmental knowledge is inversely associated with climate change anxiety. Climatic Change. 2023, 176, 32. [CrossRef]

- Tilikidou, I. The effects of knowledge and attitudes upon Greeks’ pro-environmental purchasing behaviour. Corporate Soc Respons and Environ Man. 2007, 14, 121–134. [CrossRef]

- Searle, K., & Gow, K. Do concerns about climate change lead to distress? International Journal of Climate Change Strat and Man. 2010, 2, 362–379. [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L. V., Escario, J.-J., & Rodriguez-Sanchez, C. Analyzing differences between different types of pro-environmental behaviors: Do attitude intensity and type of knowledge matter? Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2019, 149, 56–64. [CrossRef]

- McBride, S. E. , Hammond, M. D., Sibley, C. G., & Milfont, T. L. Longitudinal relations between climate change concern and psychological wellbeing. Journal of Environ Psych. 2021, 78, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. Normative influences on altruism. In Adv in exp soc psych, Academic Press: 1977; pp. 221-279. [CrossRef]

- Nigbur, D. , Lyons, E., & Uzzell, D. Attitudes, norms, identity and environmental behaviour: Using an expanded theory of planned behaviour to predict participation in a kerbside recycling programme. British Journal of Soc Psych. 2010, 49, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K. S. , McDonald, R., & Louis, W. R. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. Journal of Environ Psych. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F. , Hübner, G., & Bogner, F. Contrasting the Theory of Planned Behavior With the Value-Belief-Norm Model in Explaining Conservation Behavior. Journal of Applied Soc Psych. 2006, 35, 2150–2170. [CrossRef]

- Faletar, I. , Kovačić, D., & Cerjak, M. Purchase of organic vegetables as a form of pro-environmental behaviour: Application of norm activation theory. Journal of Central Euro Agri. 2021, 22, 211–225, Scopus. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, F. , & Hansstein, F. V. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. Journal of Cleaner Prod. 2017, 142, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A. , Boiral, O., & Guillaumie, L. Evaluating determinants of employees’ pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Int Journal of Manpower. 2020, 41, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werff, E. , Steg, L., & Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. Journal of Environ Psych. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B. , Murtagh, N., & Abrahamse, W. Values, identity and pro-environmental behaviour. Contemp Soc Sci. 2014, 9, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kort, Y. A. W. , McCalley, L. T., & Midden, C. J. H. Persuasive Trash Cans: Activation of Littering Norms by Design. Environ and Beh. 2008, 40, 870–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. , & Schmidt, P. Incentives, Morality, Or Habit? Predicting Students’ Car Use for University Routes With the Models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ and Beh. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. , & Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Environ Psych. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y. , Adhikari, P., & Sheffield, D. Mental health of UK hospitality workers: Shame, self-criticism and self-reassurance. The Service Industries Journal. 2019, 41, 1076–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. , Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of personality and soc psych 1988, 54, 1063. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J. R. , & Henry, J. D. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clin Psych. 2004, 43, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, C. , Sherman, D. K., & Kim, H. S. “Green to be seen” and “brown to keep down”: Visibility moderates the effect of identity on pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environ Psych. 2017, 51, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark-Carter, D. Quantitative psychological research: The complete student’s companion. Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2018.

- Kotera, Y., Mayer, C.-H., & Vanderheiden, E. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Mental Health Between German and South African Employees: Shame, Self-Compassion, Work Engagement, and Work Motivation. Frontiers in Psych. 2021, 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.627851.

- Kotera, Y. , Richardson, M., & Sheffield, D. Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int Journal of Mental Health and Addic. 2022, 20, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. , Marks, E., & Dobromir, A. I. On the nature of eco-anxiety: How constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? Journal of Environ Psych. 2020, 72, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 54. Kotera, Y., Van Laethem, M., & Ohshima, R. Cross-cultural comparison of mental health between Japanese and Dutch workers: Relationships with mental health shame, self-compassion, work engagement and motivation. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management. 2020, 27, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y., Kirkman, A., Beaumont, J., Komorowska, M. A., Such, E., Kaneda, Y., & Rushforth, A. Self-Compassion during COVID-19 in Non-WEIRD Countries: A Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2023, 11, Article 14. [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y. , Taylor, E., Brooks-Ucheaga, M., & Edwards, A.-M. Need for a tool to inform cultural adaptation in mental health interventions. Int Journal of Beh Develop 2023, pp. 2–5.

- Kotera, Y. , Chircop, J., Hutchinson, L., Rhodes, C., Green, P., Jones, R.-M., Kaluzeviciute, G., & Garip, G. Loneliness in online students with disabilities: Qualitative investigation for experience, understanding and solutions. Int Journal of Edu Tech in Higher Edu. 2021, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y. , Rennick-Egglestone, S., Ng, F., Llewellyn-Beardsley, J., Ali, Y., Newby, C., Fox, C., Slade, E., Bradstreet, S., Harrison, J., Franklin, D., Todowede, O., & Slade, M. Assessing Diversity and Inclusivity is the Next Frontier in Mental Health Recovery Narrative Research and Practice. JMIR Mental Health. 2023, 10, e44601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y. , Rawson, R., Okere, U., Brooks-Ucheaga, M., Williams, A., Chircop, J., Lyte, G., Spink, R., & Green, P. Teaching sustainability to online healthcare students: A viewpoint. Int Journal of Higher Ed and Sust. 2022, 4, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Climate Change Exposure group (n=55) | Control group (n=45) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants characteristics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 14 (25.45%) | 11 (24.44%) | |

| Female | 39 (70.91%) | 32 (71.11%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (1.82%) | 1 (2.22%) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (2.22%) | ||

| Transgender and non-binary | 1 (1.82%) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 39 (70.91%) | 34 (75.56%) | |

| Non-white | 16 (29.09%) | 11 (24.44%) | |

| Age (years) | 33.62 (14.84) | 33.48 (14.53) | |

| Participant-rated outcome scores (Baseline) | |||

| PANAS (n=100) | |||

| Negative affect | 18.49 (8.18) | 17.40 (7.94) | |

| Positive affect | 27.55 (8.49) | 27.06 (10.03) | |

| PEBI (n=100) | |||

| Intentions | 63.82 (9.42) | 60.87 (11.94) |

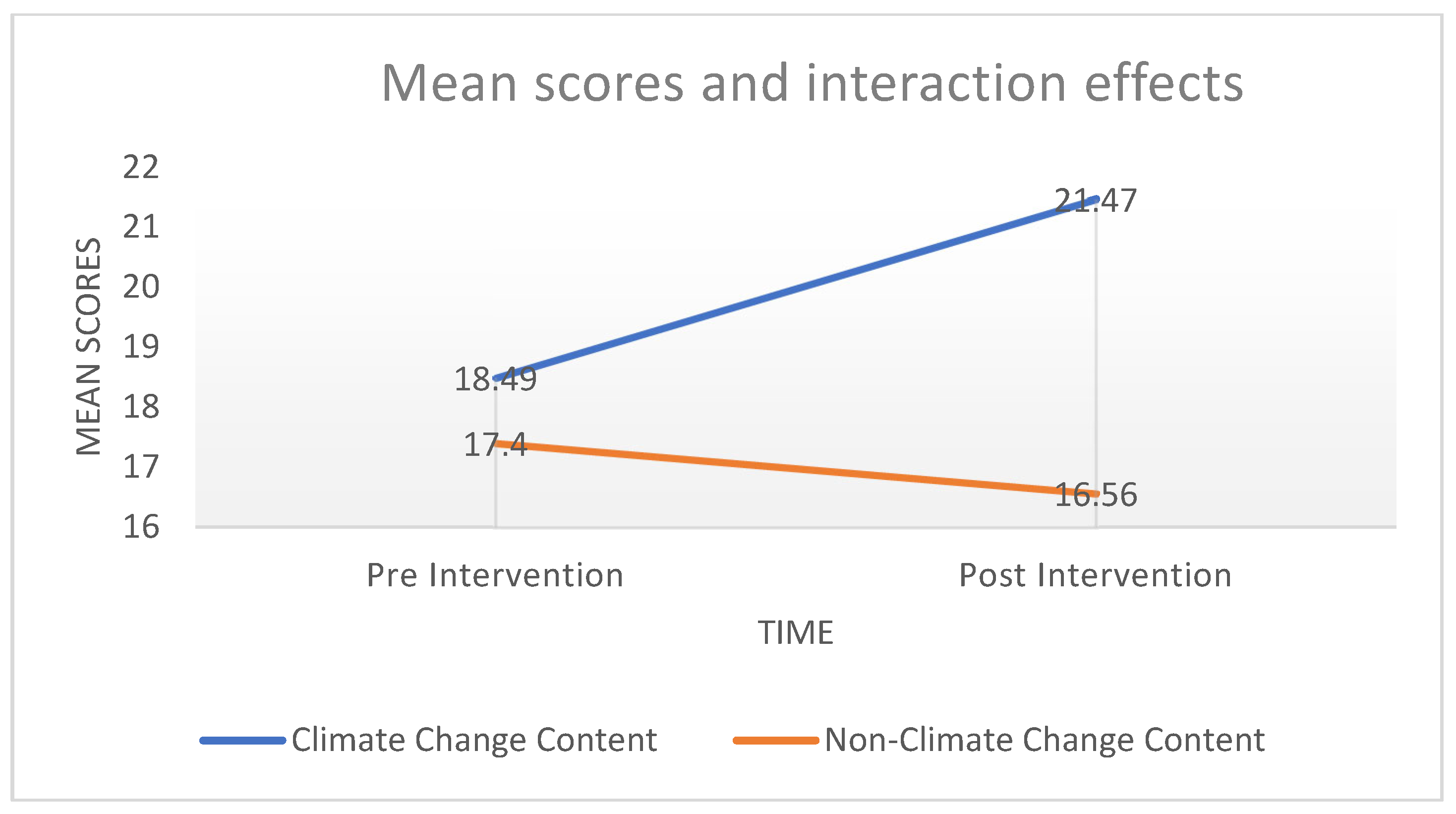

| Negative affect scores (pre) | Negative affect scores (post) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change content | 18.49 (8.18) | 21.47 (9.14) | 19.98 (8.77) |

| Non-climate change content | 17.40 (7.94) | 16.56 (8.37) | 16.98 (8.12) |

| Total | 17.95 (8.06) | 19.02 (8.76) |

| Positive affect scores (pre) | Positive affect scores (post) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change content | 27.55 (8.49) | 27.16 (8.21) | 27. 35 (8.32) |

| Non-climate change content | 27.06 (10.03) | 25.76 (10.69) | 26.41 (10.33) |

| Total | 27.31 (9.26) | 26.46 (9.45) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).