Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

28 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

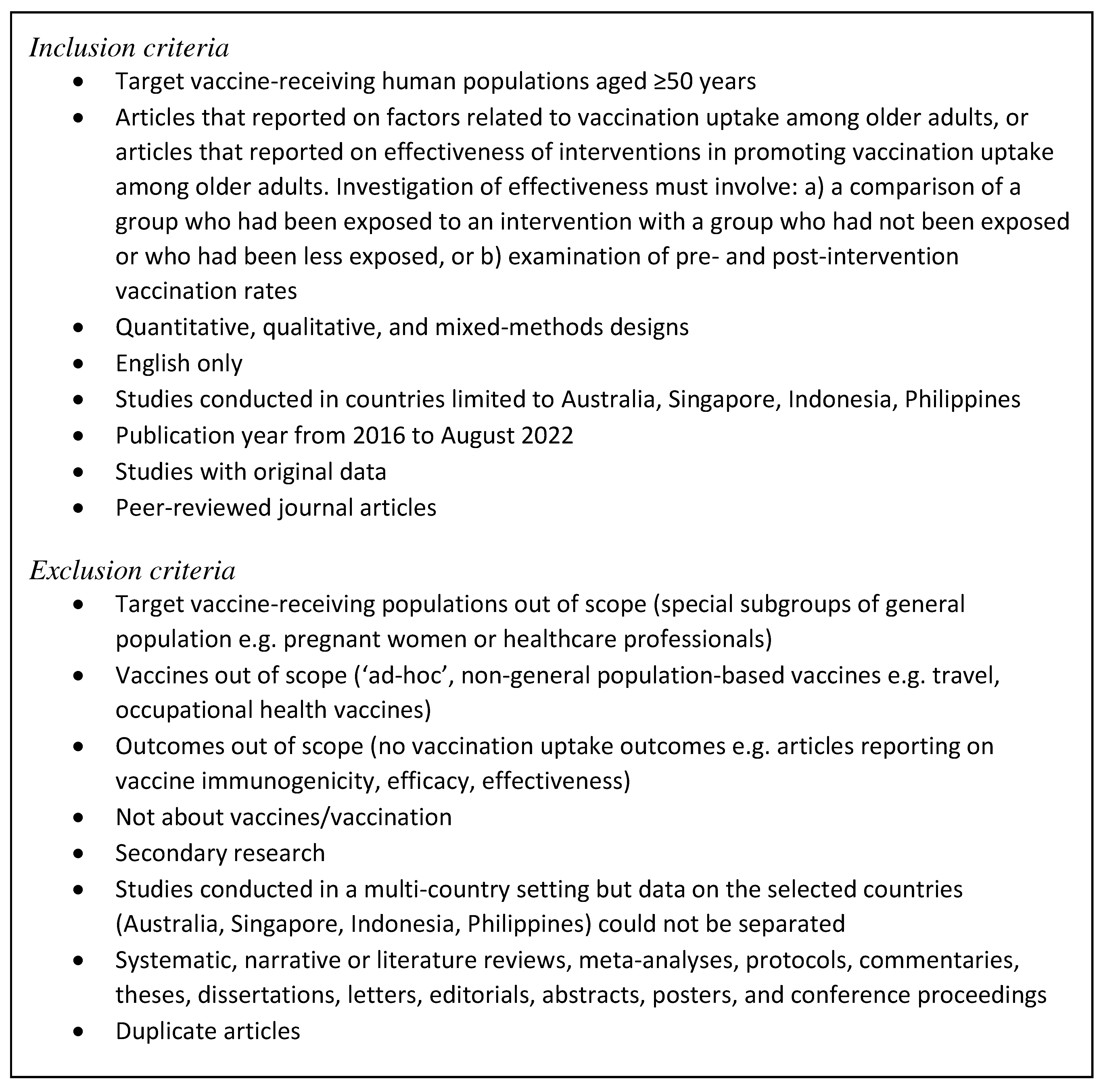

Methods

Search strategy

Literature selection

Data extraction

Risk of bias assessment

Data analysis and reporting

Results

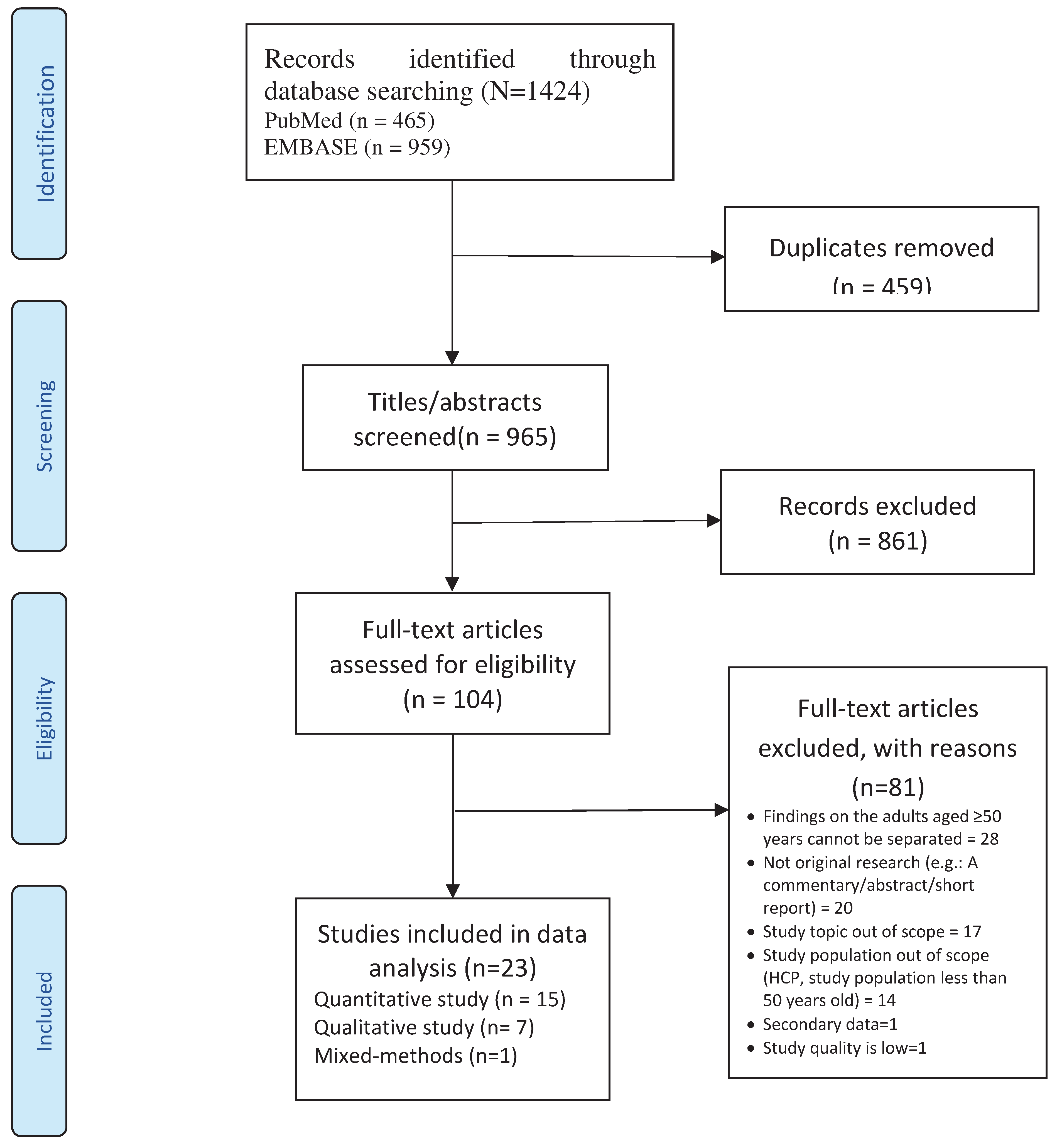

Literature selection

Study characteristics

Studies on intervention effectiveness

Risk of bias in studies

Individual characteristics

Knowledge and awareness of vaccine and immunization

Past vaccination experience or infection

Perceived health status and co-morbidities

Attitudes and beliefs

Perceived benefits of vaccine

Perceived vaccine safety and effectiveness

Social responsibility

Trust

Perceived susceptibility

Personal health beliefs and practices

Religion and fatalism

Interpersonal

Social influence

Having a regular family doctor/GP

Community

Discussions

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. WHO's work on the UN Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030) 2023 [Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing.

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Population ageing: A human success story 2023 [Available from: https://www.population-trends-asiapacific.org/population-ageing.

- United Nations ESCAP. Addressing the Challenges of Population Ageing in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok; 2017.

- Seth, A., Pangestu, T. Promoting older adults immunisation. A pathway to healthy ageing in Asia Pacific. 2022.

- Bhanu, C., Gopal, D.P., Walters, K., Chaudhry, U.A.R. Vaccination uptake amongst older adults from minority ethnic backgrounds: A systematic review. PLoS Med. 2021, 18(11), e1003826. [CrossRef]

- Kan, T., Zhang, J. Factors influencing seasonal influenza vaccination behaviour among elderly people: a systematic review. Public Health. 2018, 156, 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H., Li Chen, L., Lim, K.W., Chang, W.T., Mamun, K. Vaccination in Older Adults in Singapore: A Summary of Recent Literature. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 2015, 24(2), 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.T., Kang, A.Y., Lewis, J., Xavioer, S., Portillo, I., Goad, J.A. Addressing common barriers in adult immunizations: a review of interventions. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019, 18(11), 1167-85. [CrossRef]

- Eiden, A.L., Barratt, J., Nyaku, M.K. A review of factors influencing vaccination policies and programs for older adults globally. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023, 19(1), 2157164. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Ageing in the Asian and Pacific Region: An overview. Bangkok; 2017.

- The World Bank. Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) - Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia 2019 [Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.65UP.TO.ZS?contextual=default&end=2019&locations=MY-SG-TH-VNPH-ID&start=2019&view=bar.

- Western Pacific Pharmaceutical Forum. The Decade of Healthy Ageing in ASEAN: Role of Life-course Immunisation. 2019.

- Garritty, C., Gartlehner, G., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., King, V.J., Hamel, C., Kamel, C., Affengruber, L., Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021, 130, 13-22. [CrossRef]

- Australia Department of Health and Aged Care. Immunisation for adults 2023 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/immunisation-for-adults.

- Ministry of Health Singapore. Expert committee on Covid-19 vaccination recommends a booster dose of MRNA Covid-19 vaccine for persons aged between 50 and 59 years, six months after completion of their primary series 2021 [Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/expert-committee-on-covid-19-vaccination-recommends-a-booster-dose-of-mrna-covid-19-vaccine-for-persons-aged-between-50-and-59-years-six-months-after-completion-of-their-primary-series_24September2021.

- Hong, Q.N. , Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) v2018. 2018.

- Eilers, R., Krabbe, P.F., de Melker, H.E. Factors affecting the uptake of vaccination by the elderly in Western society. Prev Med. 2014, 69, 224-34. [CrossRef]

- Teo, L.M., Smith, H.E., Lwin, M.O., Tang, W.E. Attitudes and perception of influenza vaccines among older people in Singapore: A qualitative study. Vaccine. 2019, 37(44), 6665-72. [CrossRef]

- Waltz, T.J., Powell, B.J., Matthieu, M.M., Damschroder, L.J., Chinman, M.J., Smith, J.L., Proctor, E.K., Kirchner, J.E. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science. 2015, 10(1), 109. [CrossRef]

- Ang, L.W., Cutter, J., James, L., Goh, K.T. Epidemiological characteristics associated with uptake of pneumococcal vaccine among older adults living in the community in Singapore: Results from the National Health Surveillance Survey 2013. Scandinavian journal of public health. 2018, 46(2), 175-81. [CrossRef]

- Ang, L.W., Cutter, J., James, L., Goh, K.T. Factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake in older adults living in the community in Singapore. Epidemiology and Infection. 2017, 145(4), 775-86. [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, J., Randhawa, R., Oh, K.B., Kandeil, W., Jenkins, V.A., Turriani, E., Nissen, M. Perceptions of vaccine preventable diseases in Australian healthcare: focus on pertussis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021, 17(2), 344-50. [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.F., Masters, D., Massey, G. Enablers and barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake: An international study of perceptions and intentions. Vaccine. 2021, 39(36), 5116-28. [CrossRef]

- Briggs, L., Fronek, P., Quinn, V., Wilde, T. Perceptions of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine uptake by older persons in Australia. Vaccine. 2019, 37(32), 4454-9. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, C.L., Kong, W.Y., Orminski, J. A typology of beliefs and misperceptions about the influenza disease and vaccine among older adults in Singapore. PLoS One. 2020, 15(5), e0232472. [CrossRef]

- Enticott, J., Gill, J.S., Bacon, S.L., Lavoie, K.L., Epstein, D.S., Dawadi, S., Teede, H.J., Boyle, J. Attitudes towards vaccines and intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: a cross-sectional analysis - implications for public health communications in Australia. BMJ Open. 2022, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Frank, O., De Oliveira Bernardo, C., González-Chica, D.A., Macartney, K., Menzies, R., Stocks, N. Pneumococcal vaccination uptake among patients aged 65 years or over in Australian general practice. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics. 2020, 16(4), 965-71. [CrossRef]

- Graham, S., Blaxland, M., Bolt, R., Beadman, M., Gardner, K., Martin, K., Doyle, M., Beetson, K., Murphy, D., Bell, S., et al. Aboriginal peoples' perspectives about COVID-19 vaccines and motivations to seek vaccination: a qualitative study. BMJ Global Health. 2022, 7(7). [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.M., Oversby, S., Ratsch, A., Kitchener, S. COVID-19 Vaccination: An Exploratory Study of the Motivations and Concerns Detailed in the Medical Records of a Regional Australian Population. Vaccines. 2022, 10(5). [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.J., Chan, Y.Y., Ibrahim, M.A.B., Wagle, A.A., Wong, C.M., Chow, A. A formative research-guided educational intervention to improve the knowledge and attitudes of seniors towards influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017, 35(47), 6367-74. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J., Bagot, K.L., Tuckerman, J., Biezen, R., Oliver, J., Jos, C., Ong, D.S., Manski-Nankervis, J.A., Seale, H., Sanci, L., et al. Qualitative exploration of intentions, concerns and information needs of vaccine-hesitant adults initially prioritised to receive COVID-19 vaccines in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022, 46(1), 16-24.

- Lupton, D. Understandings and practices related to risk, immunity and vaccination during the Delta variant COVID-19 outbreak in Australia: An interview study. Vaccine: X. 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Wood, J.G., Bernardo, C., Stocks, N.P., Liu, B. Herpes zoster vaccine coverage in Australia before and after introduction of a national vaccination program. Vaccine. 2020, 38(20), 3646-52. [CrossRef]

- Moosa, A.S., Wee, Y.M.S., Jaw, M.H., Tan, Q.F., Tse, W.L.D., Loke, C.Y., Ee, G.L.A., Ng, C.C.D., Aau, W.K., Koh, Y.L.E., et al. A multidisciplinary effort to increase COVID-19 vaccination among the older adults. Frontiers in public health. 2022, 10, 904161. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M., Straughan, P.T., Cheong, G. Information trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst middle-aged and older adults in Singapore: A latent class analysis Approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2022, 296. [CrossRef]

- Trent, M.J., Salmon, D.A., MacIntyre, C.R. Predictors of pneumococcal vaccination among Australian adults at high risk of pneumococcal disease. Vaccine. 2022, 40(8), 1152-61. [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J., Frawley, J., Adams, J., Sibbritt, D., Steel, A., Lauche, R. Associations between complementary medicine utilization and influenza/pneumococcal vaccination: Results of a national cross-sectional survey of 9151 Australian women. Preventive Medicine. 2017, 105, 184-9. [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.J., Tan, Y.R., Cook, A.R., Koh, G., Tham, T.Y., Anwar, E., Hui Chiang, G.S., Lwin, M.O., Chen, M.I. Increasing Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccination Uptake in Seniors Using Point-of-Care Informational Interventions in Primary Care in Singapore: A Pragmatic, Cluster-Randomized Crossover Trial. American journal of public health. 2019, 109(12), 1776-83. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Dobbins, T., Wood, J.G., Hall, J.J., Liu, B. Impact of a structured older persons health assessment on herpes zoster vaccine uptake in Australian primary care. Preventive Medicine. 2022, 155. [CrossRef]

- Li, A., Chan, Y.H., Liew, M.F., Pandey, R., Phua, J. Improving Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Patients With COPD: A Pilot Project. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019, 14, 2527-33. [CrossRef]

- Yue, M., Wang, Y., Low, C.K., Yoong, J.S.Y., Cook, A.R. Optimal Design of Population-Level Financial Incentives of Influenza Vaccination for the Elderly. Value in Health. 2020, 23(2), 200-8. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A., van Hoek, A.J., Boccia, D., Thomas, S.L. Lower vaccine uptake amongst older individuals living alone: A systematic review and meta-analysis of social determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2017, 35(18), 2315-28. [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged. Immunisation for Adults and Seniors: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2017 [Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/immunisation-for-adults-and-seniors.

- Ministry of Health Singapore. Nationally Recommended Vaccines 2021 [Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/nationally-recommended-vaccines.

- Ministry of Health Singapore. Adult immunisation vaccinations take-up rate 2020 [Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/adult-immunisation-vaccinations-take-up-rate.

- Ministry of Health Singapore. White paper on healthier SG. Singapore; 2022.

- Abu-Rish, E.Y., Barakat, N.A. The impact of pharmacist-led educational intervention on pneumococcal vaccine awareness and acceptance among elderly in Jordan. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021, 17(4), 1181-9. [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, L.T., Prioli, K.M., Fields Harris, L., Cannon-Dang, E., Marthol-Clark, M., Alcusky, M., McCoy, M., Schafer, J.J. Knowledge, Activation, and Costs of the Pharmacists' Pneumonia Prevention Program (PPPP): A Novel Senior Center Model to Promote Vaccination. Ann Pharmacother. 2018, 52(5), 446-53.

- Dutta, O., Lall, P., Patinadan, P.V., Car, J., Low, C.K., Tan, W.S., Ho, A.H.Y. Patient autonomy and participation in end-of-life decision-making: An interpretive-systemic focus group study on perspectives of Asian healthcare professionals. Palliat Support Care. 2020, 18(4), 425-30. [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, A., Trinh, H.N., Weaver, S., Chernenko, A., Wright, L., Stoddard, M., Nourian, M.M., Nguyen, H. Knowledge and beliefs about HPV among college students in Vietnam and the United States. J Infect Public Health. 2018, 11(1), 120-5. [CrossRef]

- Magee, L., Knights, F., McKechnie, D.G.J., Al-Bedaery, R., Razai, M.S. Facilitators and barriers to COVID-19 vaccination uptake among ethnic minorities: A qualitative study in primary care. PLoS One. 2022, 17(7), e0270504. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A., Iqbal, B., Ehtamam, A., Rahim, M., Shaikh, H.A., Usmani, H.A., Nasir, J., Ali, S., Zaki, M., Wahab, T.A., et al. Reasons for non-vaccination in pediatric patients visiting tertiary care centers in a polio-prone country. Arch Public Health. 2013, 71(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Malone, J., Dadswell, A. The Role of Religion, Spirituality and/or Belief in Positive Ageing for Older Adults. Geriatrics (Basel). 2018, 3(2). [CrossRef]

| No | Author, year of publication (reference no) | Country where the study was conducted | Vaccine | Setting | Study population | Study design | Data analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies that identified factors related to vaccination uptake among older adults | |||||||

| 1 | Ang et al., 2018 [20] |

Singapore | Pneumococcal | Community | n=3672 Individuals ≥50 years |

Cross-sectional | Multivariate logistic regression |

| 2 | Ang et al., 2017 [21] | Singapore | Influenza | Community | n=3700 Individuals >50 years |

Cross-sectional (Retrospective analysis of the 2013 National Health Surveillance Survey (NHSS) | Multivariate logistic regression |

| 3 | Bayliss et al., 2021 [22] |

Australia | Pertussis | Community | n=6529 Individuals ≥50 years |

Cross-sectional (online survey) | t-tests, Wilcoxon Rank Sum, Fisher’s exact test, ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis tests |

| 4 | Burke et al., 2021 [23] |

Multicountry study: Australia, United States, England, Canada, New Zealand |

Covid-19 | Community | n=1678 (Australian respondents) Median adult age for the Australian sample is 59.5 years |

Cross-sectional | Exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) |

| 5 | Briggs et al., 2019 [24] | Australia | Influenza & Pneumococcal | Community | n=36 Individuals ≥65 years |

Qualitative study | Thematic analysis |

| 6 | Cummings et al., 2020 [25] |

Singapore | Influenza | Community | n=76 Individuals ≥65 years |

Qualitative study | Grounded theory |

| 7 | Enticott et al., 2018 [26] |

Australia | Covid-19 | Community | n=1158 Mean age of participants is 52 years |

Cross-sectional (online survey) | Multivariate logistic regression |

| 8 | Frank et al., 2020 [27] |

Australia | Pneumococcal | Electronic medical records: Hospital/clinic | n=58549 Individuals age between 60-65 years |

Retrospective cohort analysis | Logistic regression |

| 9 | Graham et al., 2022 [28] |

Australia | COVID-19 | Community | n=35 Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders age ranged from 15-80 years old |

Qualitative study | Thematic analysis |

| 10 | Hamilton et al., 2022 [29] |

Australia | Covid-19 | Clinic | n=102 (<50=6; 50–59=13, 60–69=42, 70–79=28, ≥80=13) 80 % of study population is more than 60 years old |

Qualitative study | Thematic analysis |

| 11 | Ho et al., 2017 [30] |

Singapore | Influenza & Pneumococcal | Community | n=32 Individuals ≥60 years |

Mixed-method study Qualitative study in a larger intervention study |

Logistic regression model Thematic analysis |

| 12 | Kaufman et al., 2022 [31] |

Australia | Covid-19 | Community | n=19 Individuals aged ≥70 years |

Qualitative study | Descriptive thematic analysis |

| 13 | Lupton., 2022 [32] |

Australia | Covid-19 | Community | n=20 Individuals ≥50 years |

Qualitative study | Thematic analysis |

| 14 | Lin et al., 2020 [33] |

Australia | Herpes Zoster | Electronic medical records: Clinic | n=52,229 (2016 cohort), N=55,034 (2017 cohort), and N=57,316 (2018 cohort) Individuals age between 50-90 years |

Retrospective cohort study | Multivariate logistic regression |

| 15 | Moosa et al., 2022 [34] |

Singapore | Covid-19 | Community | n=21663 Unvaccinated older adults ≥60 years |

Cohort study | Descriptive analysis |

| 16 | Tan et al., 2022 [35] |

Singapore | Covid-19 | Community | n=6094 Individuals aged 56-75 years old |

Cross sectional study (Retrospective analysis of data from the Singapore Life Panel population survey of Singaporeans aged 56–75) | Logistic regression |

| 17 | Trent et al., 2020 [36] |

Australia | Pneumococcal | Community | n=744 Individuals ≥65 years |

Cross-sectional (Retrospective analysis of three surveys: The Australian Adult Immunisation Survey, BREATH study, and survey on mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic (MUS). | Modified Poisson regression |

| 18 | Teo et al., 2019 [18] |

Singapore | Influenza | Clinic | n=15 Individuals aged 66-85 years |

Qualitative study | Thematic analysis |

| 19 | Wardle et al., 2017 [37] |

Australia | Influenza & Pneumococcal | Electronic medical records: Community | n=9151 Women age 62-67 years |

Cross-sectional (Retrospective analysis of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH) survey) |

Multivariate logistic regression |

| Studies that tested interventions for promoting uptake of vaccination among older adults | |||||||

| 22 | Ho et al., 2019 [38] |

Singapore | Influenza & Pneumococcal | Clinic | n=4378 Individuals ≥ 65 years (Intervention), 4459 (Control) |

A Pragmatic Cluster-Randomized Crossover Trial | Multilevel logistic regression |

| 20 | Lin et al., 2022 [39] |

Australia | Herpes Zoster | Clinic | n=31,876 Patients aged 75–79 years |

Retrospective analysis of data from the Australian national general practice electronic medical records | Generalized estimating equations for binary outcomes with logit link |

| 23 | Li et al., 2019 [40] |

Singapore | Influenza | Hospital | n=384 COPD patients. The mean age of the participants was 72.8 years |

Before–after study | Descriptive statistics, chi-square test |

| 21 | Yue et al., 2020 [41] |

Singapore | Influenza | Community | n=373 Individuals ≥ 65 years Arm 1: 166 Arm 2: 44 Arm 3: 73 Arm 4: 90 |

Randomised controlled experiment | Likelihood ratio test. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).