Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

01 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

2.2. Study measurements

2.2.1. Demographic, lifestyle and clinical data

2.2.2. Symptom scales

2.3. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

3.2. Symptom clusters

3.3. Longitudinal analyses

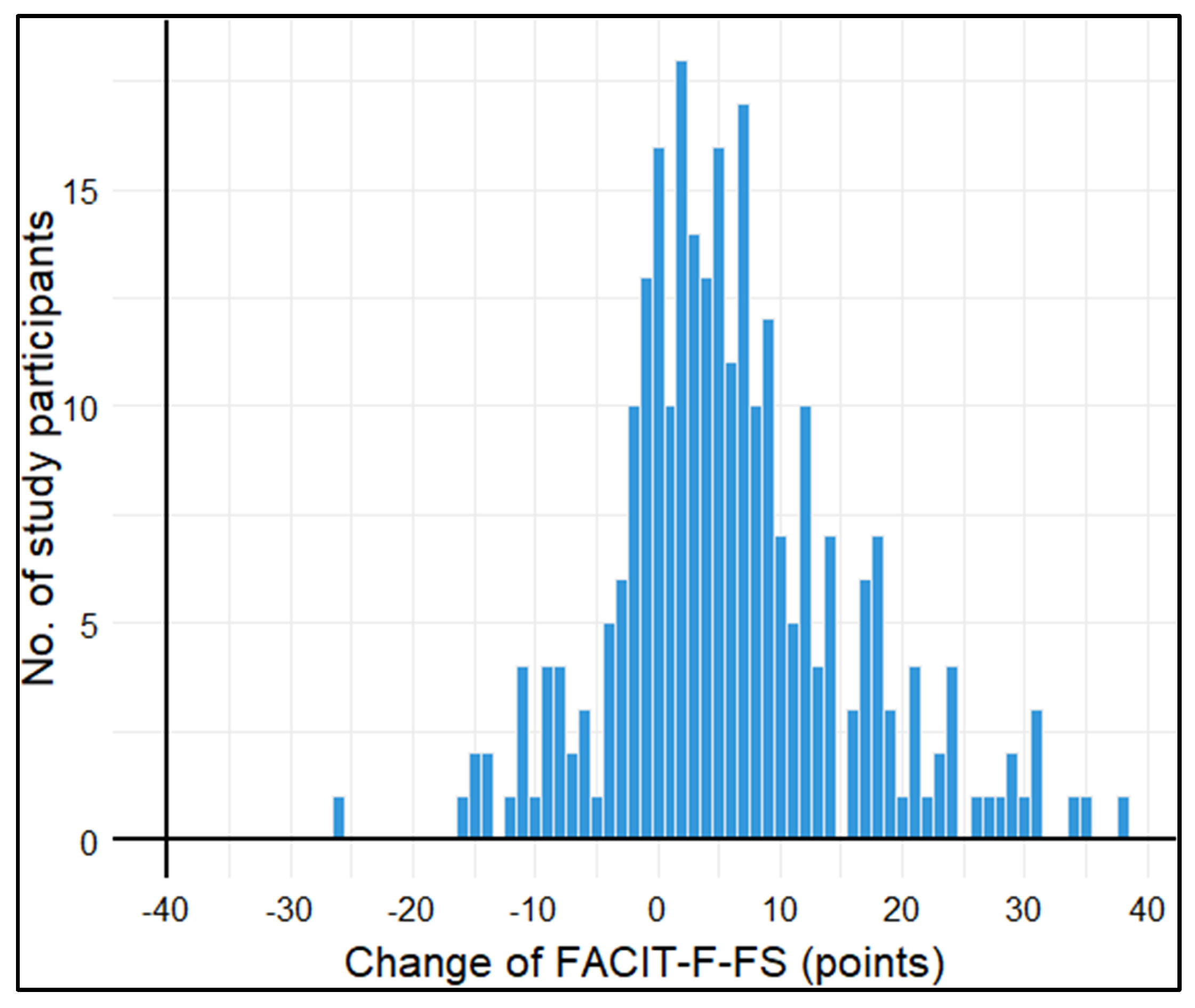

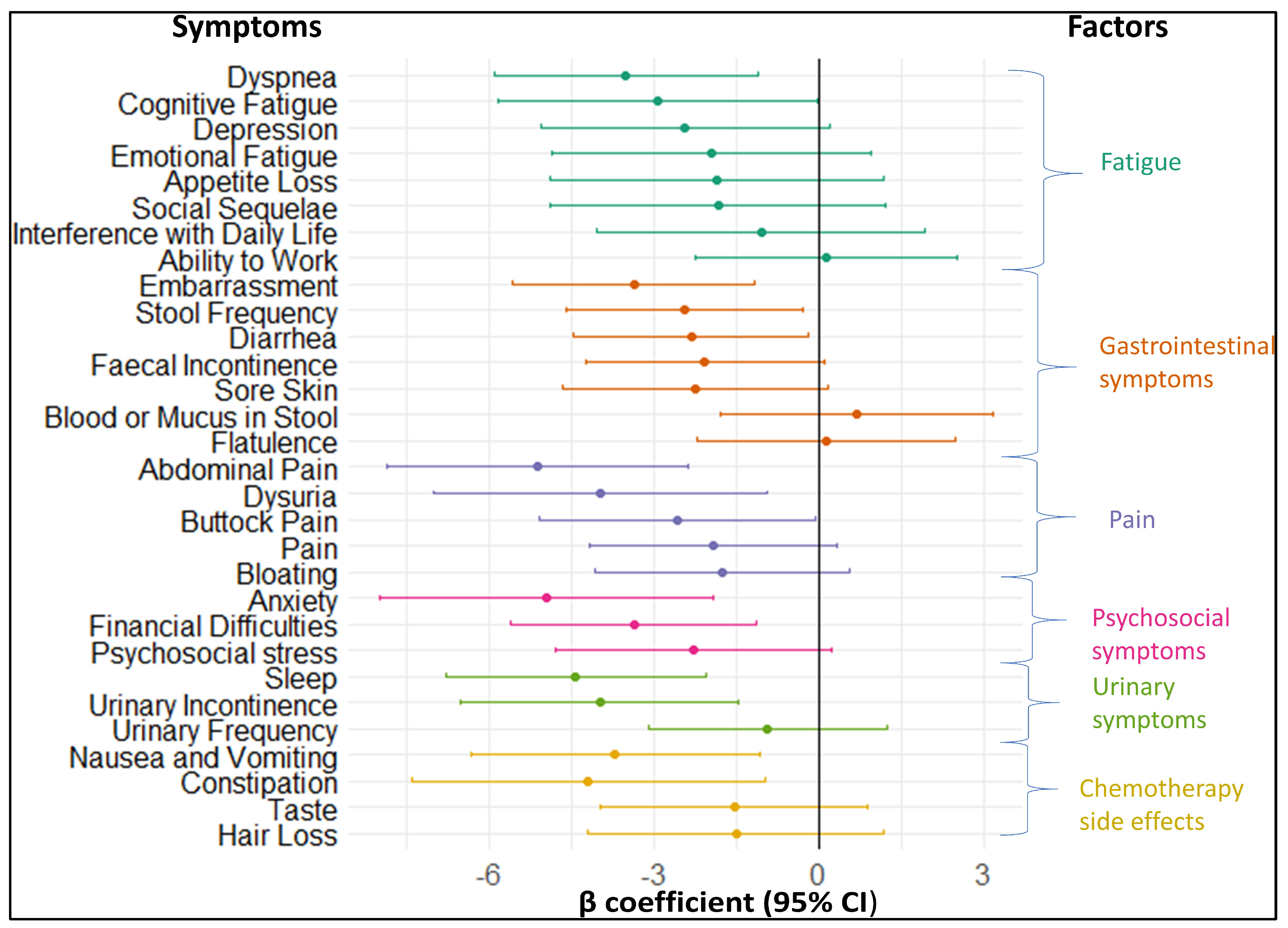

3.3.1. Longitudinal association of baseline symptoms with fatigue

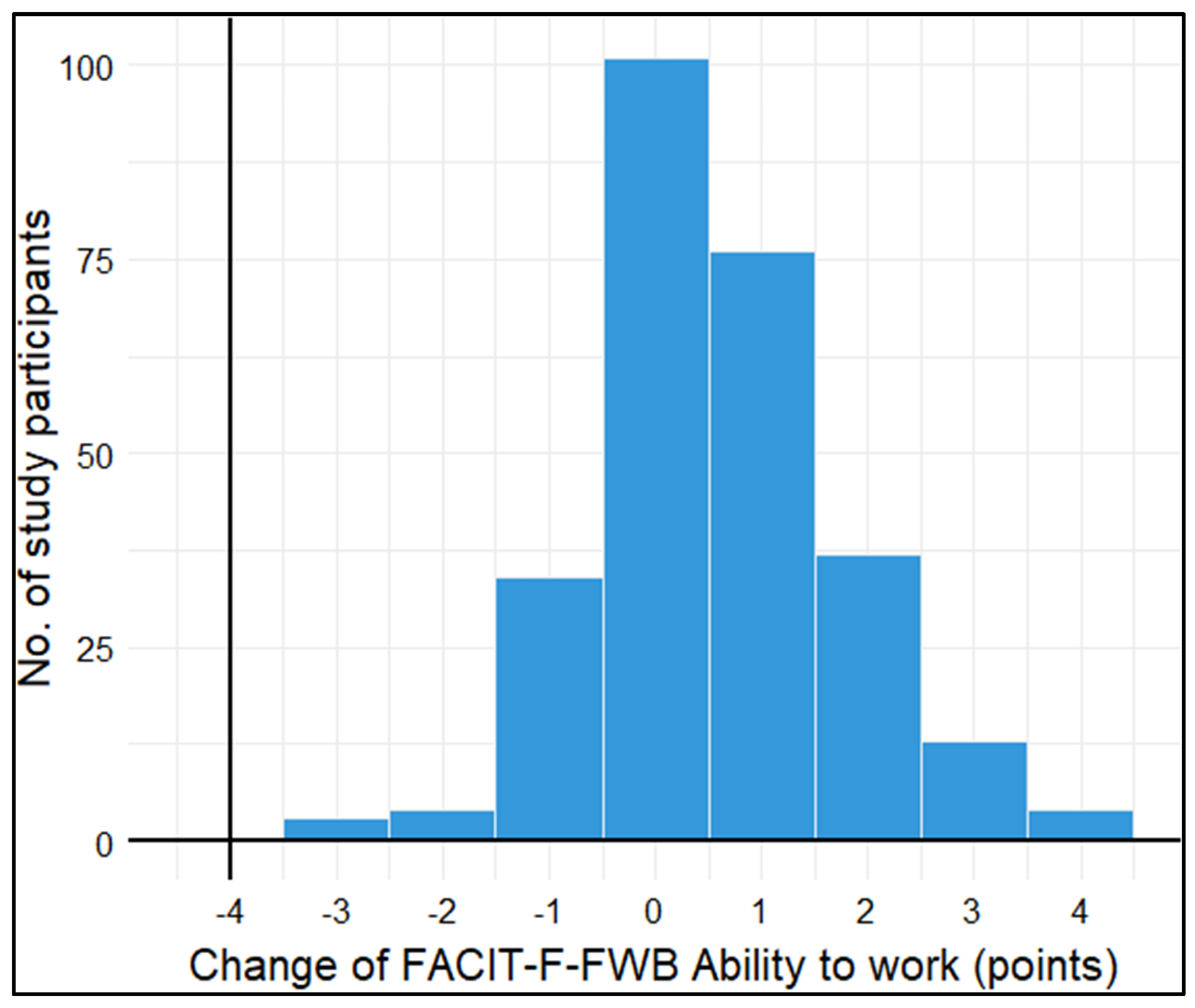

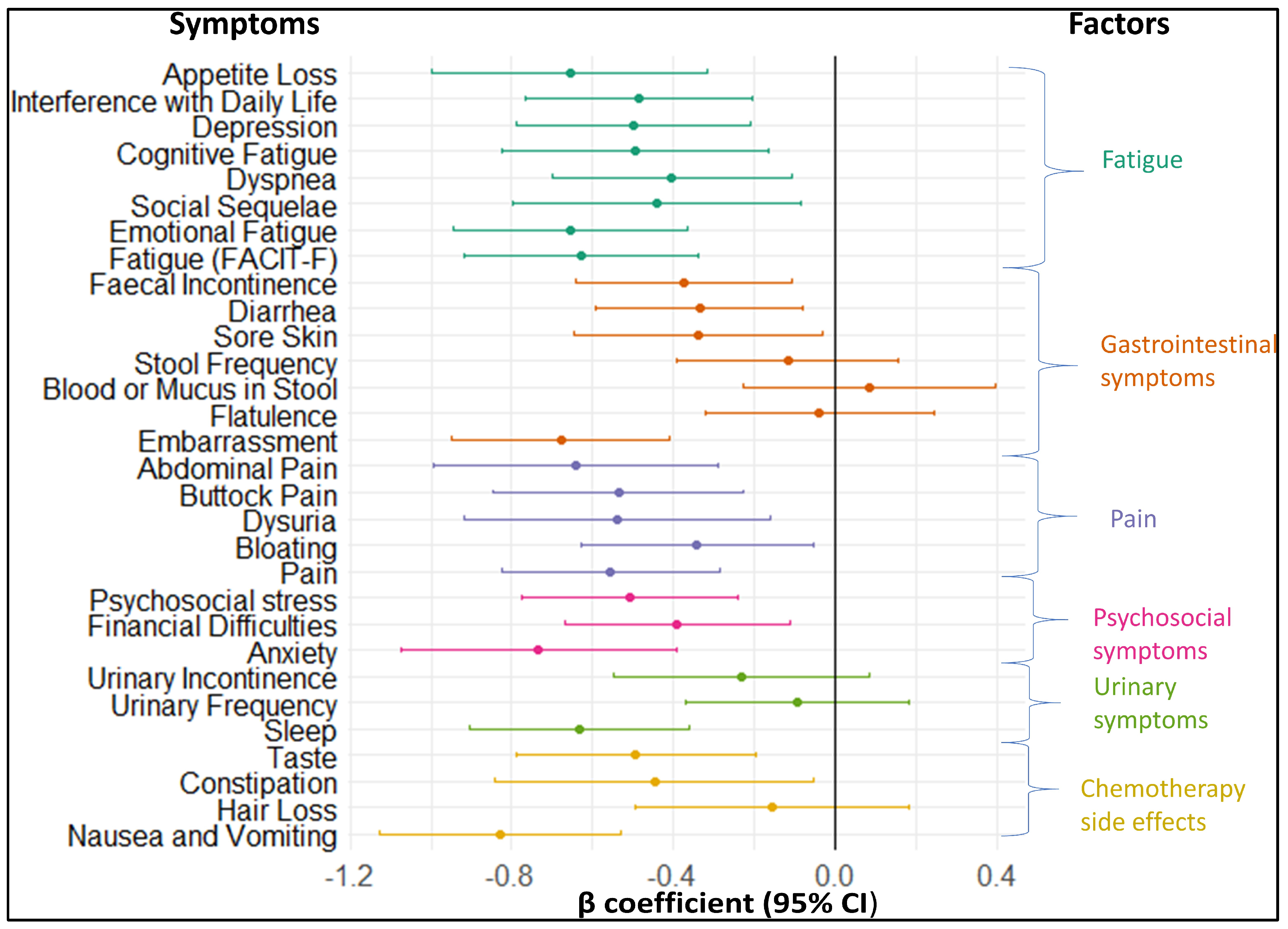

3.3.2. Longitudinal association of baseline symptoms with ability to work

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hofman, M.; Ryan, J.L.; Figueroa-Moseley, C.D.; Jean-Pierre, P.; Morrow, G.R. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist 2007, 12 Suppl 1, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.J.; Yang, G.S.; Syrjala, K. Symptom Experiences in Colorectal Cancer Survivors After Cancer Treatments: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs 2020, 43, E132–E158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.N.; Huang, M.L.; Kao, C.H. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety in Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinska, A.; Wlodarczyk, M.; Makaro, A.; Salaga, M.; Fichna, J. Management of pain in colorectal cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021, 157, 103122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senapati, S.; Mahanta, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Maiti, P. Controlled drug delivery vehicles for cancer treatment and their performance. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2018, 3, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carelle, N.; Piotto, E.; Bellanger, A.; Germanaud, J.; Thuillier, A.; Khayat, D. Changing patient perceptions of the side effects of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer 2002, 95, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, A.; Haas, M.; Viney, R.; Pearson, S.A.; Haywood, P.; Brown, C.; Ward, R. Incidence and severity of self-reported chemotherapy side effects in routine care: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0184360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German Guideline Program in Oncology (German Cancer Society, German Cancer Aid, AWMF): S3-Guideline Colorectal Cancer, long version 2.1, 2019, AWMF registrationnumber: 021-007OL, Available online: http://www.leitlinienprogrammonkologie.de/leitlinien/kolorektales-karzinom/ (accessed on 18.07.2023).

- Kuipers, E.J.; Grady, W.M.; Lieberman, D.; Seufferlein, T.; Sung, J.J.; Boelens, P.G.; van de Velde, C.J.; Watanabe, T. Colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1, 15065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birgisson, H.; Pahlman, L.; Gunnarsson, U.; Glimelius, B. Late adverse effects of radiation therapy for rectal cancer - a systematic overview. Acta Oncol 2007, 46, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guren, M.G.; Dueland, S.; Skovlund, E.; Fossa, S.D.; Poulsen, J.P.; Tveit, K.M. Quality of life during radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2003, 39, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G. A Review of the Research on Symptom Clusters in Cancer Survivors. Open Journal of Nursing 2021, 11, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Gu, L.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, H.; Qiu, Q.; Zhang, W. Symptom clusters in patients with colorectal cancer after colostomy: a longitudinal study in Shanghai. J Int Med Res 2021, 49, 3000605211063105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Ryu, E. Effects of symptom clusters and depression on the quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, S.W.; Lyon, D.; Farace, E. Symptom clusters in patients with high-grade glioma. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007, 39, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Muijen, P.; Weevers, N.L.; Snels, I.A.; Duijts, S.F.; Bruinvels, D.J.; Schellart, A.J.; van der Beek, A.J. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013, 22, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D.; Rajacich, D.; Andary, C. Experiences of cancer patients’ return to work. Can Oncol Nurs J 2020, 30, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavan, H.; Azadi, A.; Veisani, Y. Return to Work in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Indian J Palliat Care 2019, 25, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.J.; Yip, S.Y.C.; Chan, R.J.; Chew, L.; Chan, A. Investigating how cancer-related symptoms influence work outcomes among cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2022, 16, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaski, T.; Slavic, M.; Caspari, R.; Fischer, H.; Brenner, H.; Schottker, B. Development Trajectories of Fatigue, Quality of Life, and the Ability to Work among Colorectal Cancer Patients in the First Year after Rehabilitation-First Results of the MIRANDA Study. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schottker, B.; Kuznia, S.; Laetsch, D.C.; Czock, D.; Kopp-Schneider, A.; Caspari, R.; Brenner, H. Protocol of the VICTORIA study: personalized vitamin D supplementation for reducing or preventing fatigue and enhancing quality of life of patients with colorectal tumor - randomized intervention trial. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, D.F.; Tulsky, D.S.; Gray, G.; Sarafian, B.; Linn, E.; Bonomi, A.; Silberman, M.; Yellen, S.B.; Winicour, P.; Brannon, J.; et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993, 11, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Belle, S.; Paridaens, R.; Evers, G.; Kerger, J.; Bron, D.; Foubert, J.; Ponnet, G.; Vander Steichel, D.; Heremans, C.; Rosillon, D. Comparison of proposed diagnostic criteria with FACT-F and VAS for cancer-related fatigue: proposal for use as a screening tool. Support Care Cancer 2005, 13, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesinger, J.M.; Loth, F.L.C.; Aaronson, N.K.; Arraras, J.I.; Caocci, G.; Efficace, F.; Groenvold, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Ramage, J.; et al. Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J Clin Epidemiol 2020, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whistance, R.N.; Conroy, T.; Chie, W.; Costantini, A.; Sezer, O.; Koller, M.; Johnson, C.D.; Pilkington, S.A.; Arraras, J.; Ben-Josef, E.; et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of the EORTC QLQ-CR29 questionnaire module to assess health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 3017–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis, J.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Hammerlid, E.; Ignacio Arraras, J.; Conroy, T.; Lanceley, A.; Schmidt, H.; Wirtz, M.; Singer, S.; Pinto, M.; et al. International Psychometric Validation of an EORTC Quality of Life Module Measuring Cancer Related Fatigue (EORTC QLQ-FA12). J Natl Cancer Inst 2017, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, M.; Nowe, E.; Hofmeister, D.; Kuhnt, S.; Leuteritz, K.; Sender, A.; Stobel-Richter, Y.; Geue, K. Psychometric properties of the fatigue questionnaire EORTC QLQ-FA12 and proposal of a cut-off value for young adults with cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Book, K.; Marten-Mittag, B.; Henrich, G.; Dinkel, A.; Scheddel, P.; Sehlen, S.; Haimerl, W.; Schulte, T.; Britzelmeir, I.; Herschbach, P. Distress screening in oncology-evaluation of the Questionnaire on Distress in Cancer Patients-short form (QSC-R10) in a German sample. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.F.; Finan, C. Linear regression and the normality assumption. J Clin Epidemiol 2018, 98, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassiri, V.; Lovik, A.; Molenberghs, G.; Verbeke, G. On using multiple imputation for exploratory factor analysis of incomplete data. Behav Res Methods 2018, 50, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.M.; Mooney, K.; Alvarez-Perez, A.; Breitbart, W.S.; Carpenter, K.M.; Cella, D.; Cleeland, C.; Dotan, E.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Escalante, C.P.; et al. Cancer-Related Fatigue, Version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015, 13, 1012–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.S.; Seo, W.S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the correlates of cancer-related fatigue. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2011, 8, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chardalias, L.; Papaconstantinou, I.; Gklavas, A.; Politou, M.; Theodosopoulos, T. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Colorectal Cancer Patients: Is Preoperative Intravenous Iron Infusion Indicated? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Cancer Diagn Progn 2023, 3, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agasi-Idenburg, S.C.; Thong, M.S.; Punt, C.J.; Stuiver, M.M.; Aaronson, N.K. Comparison of symptom clusters associated with fatigue in older and younger survivors of colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer 2017, 25, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Rooij, B.H.; Oerlemans, S.; van Deun, K.; Mols, F.; de Ligt, K.M.; Husson, O.; Ezendam, N.P.M.; Hoedjes, M.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Schoormans, D. Symptom clusters in 1330 survivors of 7 cancer types from the PROFILES registry: A network analysis. Cancer 2021, 127, 4665–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storey, S.; Luo, X.; Ren, J.; Huang, K.; Von Ah, D. Symptom Clusters in Patients With Colorectal Cancer and Diabetes Over Time. Oncol Nurs Forum 2023, 50, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Garzon, M.; Postigo-Martin, P.; Gonzalez-Santos, A.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Achalandabaso-Ochoa, A.; Fernandez-Perez, A.M.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I. Colorectal cancer pain upon diagnosis and after treatment: a cross-sectional comparison with healthy matched controls. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30, 3573–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, K.; Lyleroehr, M.; Shaunfield, S.; Lacson, L.; Corona, M.; Kircher, S.; Nittve, M.; Cella, D. Neuropathy experienced by colorectal cancer patients receiving oxaliplatin: A qualitative study to validate the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy/Gynecologic Oncology Group-Neurotoxicity scale. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2020, 12, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, A.R.; Thyo, A.; Emmertsen, K.J.; Laurberg, S. Chronic pain after rectal cancer surgery - development and validation of a scoring system. Colorectal Dis 2019, 21, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.T.; Butow, P.N.; Costa, D.S.; Lovell, M.R.; Agar, M. Symptom clusters in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review of observational studies. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014, 48, 411–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Bakker, C.M.; Anema, J.R.; Huirne, J.A.F.; Twisk, J.; Bonjer, H.J.; Schaafsma, F.G. Predicting return to work among patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2020, 107, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El Aleem, E.M.; Selim, N.F.M.; Abdallah, A.M.; Amin, S.I. Assessment of Depression and Anxiety in Colorectal Cancer Patients: Review Article. The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine 2023, 92, 2630–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potosky, A.L.; Graves, K.D.; Lin, L.; Pan, W.; Fall-Dickson, J.M.; Ahn, J.; Ferguson, K.M.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Paddock, L.E.; Wu, X.C.; et al. The prevalence and risk of symptom and function clusters in colorectal cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2022, 16, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberman, D.; Mehus, B.; Elliott, S.P. Urinary adverse effects of pelvic radiotherapy. Transl Androl Urol 2014, 3, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İnsaf ALTUN, A.S. The Most Common Side Effects Experienced by Patients Were Receiving First Cycle of Chemotherapy. Iran J Public Health 2018, 47, 1218–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Filipczak, L.; Chow, E. Symptom clusters in cancer patients: a review of the literature. Curr Oncol 2007, 14, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.T.; Costa, D.S.; Butow, P.N.; Lovell, M.R.; Agar, M.; Velikova, G.; Teckle, P.; Tong, A.; Tebbutt, N.C.; Clarke, S.J.; et al. Symptom Clusters in Advanced Cancer Patients: An Empirical Comparison of Statistical Methods and the Impact on Quality of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016, 51, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsberth, C.; Sackmann, V.; Fransson, K.; Jakobsson, M.; Karlsson, M.; Milberg, A. Symptom clusters in palliative-stage cancer correlate with proinflammatory cytokine cluster. Ann Palliat Med 2023, 12, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.J.; Reding, K.W.; Kalady, M.F.; Yung, R.; Greenlee, H.; Paskett, E.D. Factors associated with long-term gastrointestinal symptoms in colorectal cancer survivors in the women’s health initiatives (WHI study). PLoS One 2023, 18, e0286058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, D.D.; Pimenta, C.A.; Caponero, R. Fatigue in colorectal cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 2012, 20, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wind, A.; Tamminga, S.J.; Bony, C.A.G.; Diether, M.; Ludwig, M.; Velthuis, M.J.; Duijts, S.F.A.; de Boer, A.G.E.M. Loss of Paid Employment up to 4 Years after Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis—A Nationwide Register-Based Study with a Population-Based Reference Group. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zheng, B.; Daines, L.; Sheikh, A. Long-Term Sequelae of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of One-Year Follow-Up Studies on Post-COVID Symptoms. Pathogens 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Baseline characteristics | Ntotal | Proportion (%) | Median (Q1-Q3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 394 | 62 (56 - 71) | |

| <65 | 222 (56.3) | ||

| ≥65 | 172 (43.7) | ||

| Sex | 394 | ||

| Female | 166 (42.1) | ||

| Male | 228 (57.9) | ||

| Cancer stage | 375 | ||

| I | 117 (31.2) | ||

| II | 120 (32.0) | ||

| III | 99 (26.4) | ||

| IV | 23 (6.1) | ||

| Unknown | 16 (4.3) | ||

| Type of CRC treatment | |||

| Surgery | 389 | 386 (99.2) | |

| Chemotherapy | 382 | 176 (46.1) | |

| Radiotherapy | 378 | 79 (20.9) | |

| Months since CRC surgery | 383 | ||

| 0–1 | 162 (42.3) | ||

| 2–3 | 62 (16.2) | ||

| 4–6 | 48 (12.5) | ||

| 7–9 | 62 (16.2) | ||

| 10–12 | 34 (8.9) | ||

| >12 | 15 (3.9) | ||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m²) | 394 | 26.2 (23.1 – 29.6) | |

| <25 | 161 (40.9) | ||

| 25 to <30 | 144 (36.5) | ||

| ≥30 | 89 (22.6) | ||

| Smoking status | 373 | ||

| Never smoked | 159 (42.6) | ||

| Former smoker | 161 (43.2) | ||

| Current smoker | 53 (14.2) | ||

| Healthy physical activity level a | 368 | 175 (47.5) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 371 | 64 (17.3) | |

| Hypertension | 368 | 194 (52.7) | |

| History of myocardial infarction | 370 | 13 (3.5) | |

| History of stroke | 371 | 14 (3.8) | |

| Number of comorbidities | 374 | 2 (1 – 2) | |

| 0 | 66 (17.7) | ||

| 1 | 109 (29.1) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 199 (53.2) | ||

| Employment status | 386 | ||

| Fully employed | 188 (48.7) | ||

| Part-time employed | 36 (9.3) | ||

| Retired | 150 (38.9) | ||

| Unemployed | 12 (3.1) |

| Symptoms | Factor 1 “Fatigue” |

Factor 2 “Gastro- intestinal symptoms” |

Factor 3 “Pain” |

Factor 4 “Psycho- social symptoms” |

Factor 5 “Urinary symptoms” |

Factor 6 “Chemotherapy side effects” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest factor loading | ||||||

| Fatigue (FACIT F) | -0.97 | |||||

| Interference with Daily Life | 0.94 | |||||

| Emotional Fatigue | 0.80 | |||||

| Depression | 0.68 | |||||

| Cognitive Fatigue | 0.61 | |||||

| Dyspnea | 0.49 | |||||

| Social Functioning | 0.46 | |||||

| Ability to Work | -0.39 | |||||

| Appetite Loss | 0.31 | |||||

| Faecal Incontinence | 0.82 | |||||

| Stool Frequency | 0.80 | |||||

| Sore Skin | 0.65 | |||||

| Embarrassment | 0.51 | |||||

| Diarrhea | 0.45 | |||||

| Flatulence | 0.36 | |||||

| Blood/Mucus in Stool | 0.33 | |||||

| Abdominal Pain | 0.79 | |||||

| Pain | 0.73 | |||||

| Buttock Pain | 0.52 | |||||

| Bloating | 0.43 | |||||

| Dysuria | 0.35 | |||||

| Psychosocial Stress | 0.58 | |||||

| Anxiety | 0.48 | |||||

| Financial Difficulties | 0.40 | |||||

| Urinary Frequency | 0.70 | |||||

| Urinary Incontinence | 0.50 | |||||

| Sleep Disturbance | 0.33 | |||||

| Dry Mouth | 0.20 | |||||

| Taste Alteration | 0.61 | |||||

| Hair Loss | 0.44 | |||||

| Constipation | 0.32 | |||||

| Nausea or Vomiting | 0.30 | |||||

| Eigenvalue | 4.96 | 2.67 | 2.17 | 1.99 | 1.12 | 0.95 |

| Variance explained | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Proportion explained (%) | 36 | 19 | 16 | 14 | 8 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).