1. Introduction

The characteristics of responding to stressful situations depend on a complex of factors, including personality [

1], health state [

2], features of the nervous system [

3], cultural peculiarities, environment, and social context [

4]. The complex stress-associated attitude towards psychological and somatic well-being is based on trait anxiety as one of the most evident components of stress resistance (Malova Y., 2022), which can predict the life style and the risk factors of different diseases. Health state also can determine the effect of stressful experiences [

5]. The stress, as complex response, is also determined by cultural peculiarities, environment, and social context. There are some studies, reporting the correlations between perception of different modalities by Suleymanov (2023)

1 and coping with stress.

Very few studies have been conducted regarding the relationship between stress resilience and individual differences in proprioceptive accuracy of fine motor skills due to a general lack of knowledge in the area of motor control in psychology. Draganova obtained, as a result of her PhD dissertation, named “Psychophysiological markers of the juvenile tolerance” (2007) (cited in [

6]) the following myokinetical indicators [

7] of the person with high tolerance: balanced processes of excitation and inhibition, normal emotional tone, absence of hetero- or auto-aggressiveness, and overall good myokinetic balance. The study by Şenol et al. demonstrated that an increase in cortisol levels, associated with stress, negatively affects proprioception of the ankle joint, though significant differences were observed only with closed eyes [

8]. Stress factors can quickly change and impact athletic performance [

8]. An optimal level of stress has a positive effect on performance, but excessive stress can have a negative impact

2.

In a previous study, changes in proprioceptive accuracy of movements were found when switching from a single to a dual task, which corresponded to a shift towards the excitability pole in the balance of excitation-inhibition measurements [

9]. Ingram and colleagues reported a significant decrease in motor task performance efficiency in a patient with proprioceptive problems, which decreased by 60% (compared to 10% in the control group) when the motor task was switched from single to double (with subjects counting backwards, which also creates a kind of situational stress) [

10]. As other studies have shown, proprioceptive accuracy of fine motor movements is age-dependent, deteriorating during adolescence (up to 18 years old) and gradually decreasing after 50 years old due to aging processes [

11]. Individual differences in fine motor accuracy are important indicators of health and may be associated with various conditions such as Parkinson's disease [

12], adaptation to stress in sportsmen [

13], adaptation to stress in cancer patients [

1], and children with ADHD [

14,

15].

Sensory and motor deficits and associated inadequate proprioceptive feedback and impaired postural control are often seen in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy

3. In the study by Wang et al. [

16], it was found that cancer patients who underwent chemotherapy demonstrated lower accuracy and precision in sensory-motor tasks (force matching, reaching tasks, postural stability tasks) compared to an age-matched control group when relying solely on proprioceptive information to determine force. There were also small differences in the ability to maintain hand posture, but no significant differences in reaching. Proprioceptors in muscles are important for perception, coordination, and motor activities. Dysfunction can lead to difficulties with movement and posture. Chemotherapy can affect proprioception by reducing activity in sensory neurons from muscle proprioceptors during stretching [

17,

18].

However, there is another prospective field of investigation - investigation of different limitations of perception and their impact on stress-resistance and resources of psycho-social adaptation in people with the lesions of musculoskeletal system and other somatic disorders (Adeeva, 2022).

The study by Monfort et al. [

19] showed that individuals who have undergone cancer treatment rely on their vestibular system for postural control, instead of the proprioceptive system. This was discovered by measuring body deviations in response to platform tilts. Body deviations were smaller in individuals with cancer, indicating the use of vestibular signals to stabilize the body in space. Proprioceptive training has been shown to significantly improve balance outcomes in cases of peripheral neuropathy induced by chemotherapy [

20].

Proprioception plays a critical role in balance control and coordination of movement, which is essential for sports. Improving balance and balance coordination has a positive effect on athletic performance and helps prevent lower limb injuries. Proprioception plays a significant role in balance control. Ankle proprioception is critical to athletic performance and athletes with better ankle proprioception tend to perform better in their respective sports [

8,

21].

On the other hand, the investigation of proprioceptive correlates of stress-resistance parameters and complex investigation of stress and stress-resistance in cancer patients is very significant for the practical issues of cancer patients’ survival. As is well known, the diagnosis of cancer is a stressful life event for patients and might influence Quality of Life (QoL). QoL predicts survival in patients with different oncological diseases. Various studies have shown a significant relationship between quality of life and patient survival. QoL provides additional predictive information that supplements traditional clinical factors, and is a new prognostic indicator for survival of cancer patients under different treatments [

22]. Cluster grouping in bladder cancer patients suggests that patients' mental and physical functionss may not be based on disease or treatment. There are significant survival differences between all clusters, demonstrating that a holistic assessment of patient-reported health-related quality-of-life has the potential to predict survival and possible modifiable risk factors in older patients with bladder cancer [

23]. Baseline QoL is reported as a strong independent predictor of survival in patients with cancer [

24,

25,

26]. Psychological analysis of QoL self-estimation shows that this esteem is based on the actual esteem of well-being, which is the result of stress survival. Better stress survival is related to better stress resistance. Among the features of effective stress resistance in cancer patients optimism plays the significant role (Lineh 2000). The new investigations of effective coping with stress in extreme professions stress the impact of such patterns and features of stress-resistance: perseverance in the achievement of goal (Bondarenko, 2023), control and damage minimization (Leonov, 2023).

Research by Сhykhantsova & Kuprieieva reveals the pivotal role of love in fostering resilience, along with traits like dependability, sociability, achievements, hope, and trust. Serdiuk & Chykhantsova

4 further elaborate on the association between personal resilience and self-worth, acting emotional experiences, self-esteem, identity, abilities, and trust. Goncharov’s

5 study uncovers the profound link between core beliefs and emotional intelligence across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and general aspects, enabling individuals with strong core beliefs to adeptly regulate emotions and make successful decisions, while maintaining high self-esteem and a positive outlook on life.

Sheard and Golby [

27] found that hardiness is a predictor of elite-level sport performance, with commitment, control, and challenge being the three components. The Nezhad and Besharat [

28] showed that hardiness and resilience are positively correlated with sport achievement and mental health, and negatively correlated with psychological distress. The Ramzi and Besharat [

29] study emphasized the importance of developing hardiness and resilience in athletes to improve their performance and well-being.

Therefore, due to the limited number of studies, we see the need for a deeper exploration of the issue of proprioceptive indicators related to stress and other factors. This will not only expand fundamental knowledge in this area but also help develop more effective rehabilitation methods to correct these disorders that take into account not only the physical (physiological, somatic) but also the psychological aspects of restoring proprioceptive functions. Additionally, such research may lead to the development of new approaches to the prevention and treatment of stress disorders, which may affect the functioning of proprioception.

The main aims of our study were:

1) to determine the relationship between the characteristics of the proprioceptive profile of individual differences and stress resistance scales measured by the verbal test;

2) to check whether exist individual differences in the proprioceptive test outcomes in three groups;

3) to observe whether significant differences exist in the verbal stress resistance test outcomes in three groups of participants: 1) onco-patients; 2) controls; 3) sportsmen.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants. 75 participants (adults, in 3 groups: sportsmen, onco-patients and controls) performed the graphomotor Proprioceptive Diagnostics of Temperament and Character (DP-TC by Tous) and verbal test of stress resistance (adapted in Russian by Sugoniaev as a combination of Maddi’s Hardiness Survey [

30] and Janoff-Bulman’s World assumptions scale) [

31]. All subjects took part voluntarily, were informed about the aims of the research and gave consent before inclusion in the study. All tests were administered following the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration on human research.

Tools & Instruments: This study used a computerised method of individual neuropsychological assessment based on graphomotor precision - the Proprioceptive Diagnostic of Temperament and Character DP-TC [

32,

33,

34,

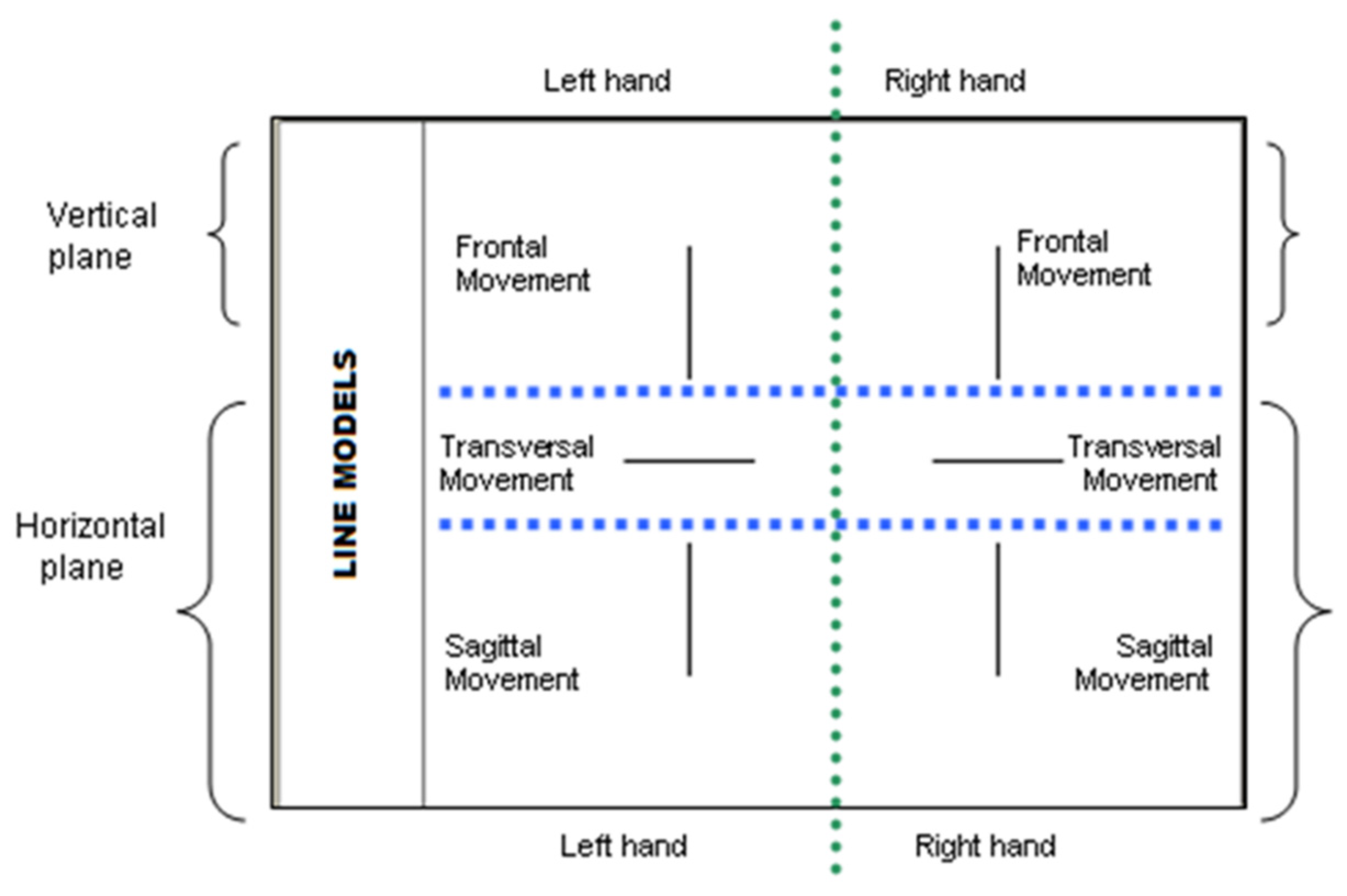

35]. The test consists in tracing lines (lineograms,

Figure 1) by both hands (d – dominant and nd – non-dominant) in different test conditions: 1) starting with vision and finishing without visual guideness (proprioceptive only), and 2) space position (F – frontal; T- transversal, and S – sagital) and hand (d – dominant and nd – non-dominant). The biases form the stimuli are measured as: 1) D - directional bias – desplacement parallelly to stimuli; 2) F – formal bias - desplacement perpendicularly to stimuli, and 2) LL – line lengh (Tous & Liutsko, 2014).

Tools for Proprioceptive Diagnostic:

Proprioceptive diagnostics of Temperament and Character (DP-TC, Tous et al., 2012) are performed with the following tools:

- A tactile screen (LGE with resolution of 1280x1024 and optimal frequency of 60 Hz) with a sensory stylus for it (for hand drawings) connected to PC.

- A specifically designed test software for the recoding and analysis of data (Tous, 2008, Tous et al., 2012).

- A piece of cardboard (or opaque screen) for non-vision part of test, to hide the active arm and movement feedback.

- A stool that can be adjusted to the participant height, and table.

- Written and oral instructions for the correct task procedure and performance.

The second test of this study was a verbal personality test for stress tolerance developed by Sugonyaev based on the versions of two psychological tests: the Hardiness Survey of Maddi [

30] in adaptation of Leontiev

6 and the World Assumptions Scale of Janoff-Bulman [

31]. The questionnaire consists of 56 statements. Participants are asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a six-point scale (Likert scale) (Appendix 1).

Variables:

DP-TC test: 5 dimensions of this test were used in this study: 1) Mood: Pessimism — Optimism (depression vs. mania); 2) Decision-making: Submission — Dominance (auto- vs. hetero- aggression); 3) Attention Style: Intra- and Extra- attention (open vs. closed); 4) Emotionality: Distant — Affectionate (cold vs. warm), and 5) Irritability: Inhibition — Excitability (inhibition vs. irritation).

Stress Resistance (SR) verbal test: 1) Trust Scale, 2) Fairness Scale, 3) Self-esteem Scale, 4) Good Luck Scale, 5) Control Scale, 6) Engagement Scale, 7) Risk Acceptance Scale, 8) Resilience (Vitality) Scale, 9) Positive Affectivity Scale.

Data analysis:

The data were categorised before analysis as follows: a) Group: 1 - patients; 2 - controls, 3 - sportsmen; b) outcomes from the SR verbal and DP-TC proprioceptive tests - normalised values were categorised as 1 - low; 2 - normal; 3 - high.

Descriptive analysis, Spearman correlation and bivariant analysis on outcomes by factor “group” (chi-square) were performed with the use of Excel and STATA.

3. Results

The descriptive statistics of the study variables, split by three participant groups (1 - patients; 2 - controls, 3 - sportsmen) are presented in

Table 1.

Weak, but statistically significant (p<.05) correlations between graphomotor proprioceptive and verbal test variables were observed (

Table 2). Higher verbal Good Luck was positively associated with Optimism in the dominant hand in the proprioceptive test. Verbal dimension Control was positively correlated with Optimism in the dominant and Inhibition in the non-dominant hand respectively in the proprioceptive graphomotor test. Similarly to the latter, verbal Resilience (Vitality) was related to proprioceptive Inhibition (non-dominant hand). Finally, verbal Positive Affect was positively correlated with proprioceptive Extra-attention (or Style of Attention towards the exterior) (

Table 2). In sum, the proprioceptive correlates of the related verbal stress resistance were observed with 4 of 9 verbal dimensions (Goodluck, Control, Resilience and Positive affect) and expressed as behavioural Optimism, Style of Attention toward exterior and Inhibition.

To observe the frequencies of participants from the three groups of the study (1 - patients, 2 - controls, 3 – sportsmen), both verbal and proprioceptive normilised variables were categorised as: 1- low, 2 - normal, 3 – high. The significant (p<.05) and marginal (p<.10) differences in group outcomes distribution as frequencies (%) are shown in

Table 3.

For the verbal test on stress Resistance, the dimensions SR1 - Trust Scale and SR2 - Fairness Scale – no statistically significant differences were observed in the three study groups. In the rest of dimensions, such as SR3 - Self-esteem, SR4 - Good Luck, SR5 - Control, SR6 - Engagement, SR7 - Risk Acceptance, SR8 - Resilience (Vitality), and SR9 - Positive Affectivity, the first group (onco-patients) have higher percentage of participants (>50%) replied in Low category (

Table 3). The biggest percentatge (73%) in Low category with 0% who replied here in High category was in onco-patients was in the SR8 - Resilience (Vitality); followed by SR3 - Self-esteem and SR5 - Control with 65% in Low categories (

Table 3).

The sportsmen were higher in the SR7 - Risk Acceptance, with 45% replies in High category compared to 19% in controls and 4% in onco-patients (

Table 3). Similar patterns, but with less magnitude of difference was observed for SR5 – Control; where sportsmen had higher percentage in High category: 35% versus 13% in onco-patients and 14% in controls. However, the sportsmen reported lower SR9 – Positive Affectiveness – with 30% in Low category compared to 10% in controls; but more than in onco-patients (57%) (

Table 3).

As far the proprioceptive graphomotor test outcomes concern, the only statistically significant differences were observed in the performance of D – directional bias in Frontal movement type and non-dominant hand (FDnd). The highest percentage in Low category (temperamental Pessimism) was represented in the group of sportsmen, showing tendency toward Pessimism of the Mood dimension: 52% versus 21% in controls and 17% in onco-patients. And inverserly, in the category High (temperamental Optimism), sportsmen replied only 4% compared to 11% in controls and 29% in onco-patients (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Higher verbal Good Luck dimension was positively associated with optimism in dominant hand in proprioceptive test that refers more to the current situational state and more conscious control of mood. There is evidence of a positive correlation of the scale of stress resistance Control and the scale of proprioceptive test Optimism. Leonov reports in his article (2023) that nurses with better stress resistance (without burnout) perform integrative factor control and Minimization of Damage. Also, Optimism is the predictor of better coping with stress in cancer patients (Lineh, 2000).

Extra-Attention(Attention towards exterior) in proprioceptive testing has got positive correlation with the Positive Affectivity Scale in verbal tests of Stress-Resistance. That corresponds to the data of disabled persons, who performed better adaptation in patients with higher levels of extraversion as a trait feature.

The presented bibliographical data suggest the significant role of some components of stress resistance in coping with extremely stressful experiences. The results obtained in our investigation make it evident that some components of stress resistance, such as Control, Positive Affectivity, Good luck plays basic integrative role in the perception of stress factors. Also pure survival with stress (according to the low levels in scales Positive Affectivity, Good luck, and Control) corresponds to typical pessimistic and introversive individuals’ results in proprioceptive testing. Stress resistance has got it’s representation on the proprioceptive level. Therefore the reciprocal relationships between proprioceptive apperception and integrative stress-resistance need perspective investigation for better prevention of undesirable effects of stress factors.

The group performance differences showed that verbal self-reported outcomes of stress resistance was lower in onco-patients for all variables, which is related how they perceive. However, the proprioceptive test showed only slightly higher Excitability in this group that didn’t reach any statistical significance and surprisinly higher Optimism, compared to other groups. In this case group of sportsmen, who were mainly students, showed more pronounced Pessimism, which is congruent with the results of earlier works, reporting higher Pessimism in students [

35].

In our study we have several limitations. It is a cross-sectional study; thus, the associations do not provide any light to cause-effect direction. The group 3 – sportsment represented mainly amateur sport practiv¡ce (there were only 3% with professional sport dedication) and this group was characterised also for major part of master's students, thus may influence more the latter status. Other limitation wss that we had 63% of the participants were women, and onco-patients were women mainly with breast cancer, and the majority were in the initial stage of illness. The effectiveness of cancer survival was not investigated. The latter can contribute to the results outcomes close to controls.

The findings described by this study can be used for betther support and healthcare of the different categories of people – patients (onco), as well as sportsmen (also represented students) in their specific moment of life that requires ore support of psychologists, therapists, coaches and healthworkers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and Y.M.; methodology, L.L, R.M, S.P.; software, R.M.; formal analysis, L.L.; investigation, L.L., Y.M., E..V., S.P., S.L.; resources, L.L.; data curation, L.L, R.M., Y.M., E..V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L, Y.M, I.P., K.V.; writing—review and editing, L.L, Y.M, I.P., E.V.; supervision, Y.M, S.L, J.G.; project administration, L.L, Y.M, S.L, J.G.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ERANET MUNDUS, grant number 2011-2573/001-001-EMA2, and partially supported by a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE University).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of MSU (protocol code 003/2014; date of approval 11/07/2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data could be provided upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all healthcare staff from oncological clinics who contributed to this study, as well as other students who helped with data collection. We express special gratitude to all volunteers who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The verbal personality test for stress tolerance developed by K. V. Sugonyaev includes 9 scales.

(1) Trust Scale. High level of trust: confidence in the friendliness of the world and the ability to trust others safely. Moderate level of trust: not blind trust, but also not complete withdrawal from others. Below average level of trust: cautious attitude towards the world and tendency to trust only a limited number of verified individuals. Low level of trust: belief in the world's hostility, the need to be constantly on guard and not trust anyone.

(2) Fairness Scale. A high level of fairness assumes that everyone gets what they deserve. A moderate level of fairness describes a balanced, ambivalent belief in fairness, where people sometimes get what they deserve. A level of fairness below average implies that luck and misfortune in a person's life depend little on their virtue. A low level of fairness believes that the laws of fairness do not apply, and luck and misfortune can happen to anyone regardless of their virtue.

(3) Self-esteem Scale. A high level of self-esteem involves the belief that the individual is a good person worthy of respect. A moderate level of self-esteem is characterized by the presence of both positive and negative aspects, and the individual believes that they are neither worse nor better than others. A level of self-esteem below average is associated with the belief that the individual is not as interesting and attractive to others as other people. A low level of self-esteem reflects the individual's belief in their worthlessness, failure, and unworthiness of respect.

(4) Good Luck Scale. A high level of luck means believing in one's own special luck and regular fortune. A moderate level of luck indicates that luck plays a relatively small or inconsistent role in life. Below average level of luck implies the belief that luck bypasses the individual or does not play an important role in their life. A low level of luck means either believing in one's unluckiness or completely denying the role of luck in life.

(5) Control Scale. At a high level, a person shows initiative, takes responsibility, and believes that their successes depend on their efforts. At a moderate level, a person acknowledges the role of external factors but also can control their life. At a low level, a person believes that their life is completely determined by external circumstances and has little opportunity to influence it.

(6) Engagement Scale. With a high level of engagement, people believe that active participation helps them find useful things for themselves and derive pleasure from their activity. With a moderate level of engagement, people have a realistic attitude towards the world, choose what they engage in, and are not overly active. With a below average level of engagement, people believe that engagement brings more troubles and therefore limit their activity. Various responsibilities are performed mechanically, with no interest in new things and self-improvement. With a low level of engagement, people believe that the world is hostile and engagement only leads to troubles, so they limit their activity. Work is done out of necessity and is not seen as a source of useful experience. Feelings of rejection and missed opportunities are present.

(7) Risk Acceptance Scale. High level of risk taking: the belief that experience and knowledge gained from risky situations contribute to personal development. Willingness to act without guarantees of success and the belief that stability and security deter from enriching experiences. Medium level of risk taking: moderate willingness to try new activities and take risks to gain new knowledge and experience through trial and error. Below average level of risk taking: willingness to avoid competition, change, and risky situations. Preference for stability, regimented activities, routine and traditional rules. Low risk-taking: a desire to avoid competition, innovation and risk-related change. Preference for stability, regulated activities, routine, traditional attitudes and rules.

(8) Resilience (Vitality) Scale. A high level of resilience is specified (characterised) by the ability to cope with stress and adapt to new conditions. This includes the ability to cope with life's difficulties without developing stress and psychosomatic problems, as well as a more developed imagination, creativity and positive emotional state. In stressful situations, people with high levels of resilience tend to use transformational coping techniques and take care of their health. An above average level of resilience implies successful overcoming of life obstacles and adaptation to new conditions with minimal risk of stress and psychosomatics.

(9) Positive Affectivity Scale. High levels of positive affectivity indicate a positive attitude toward life and optimism. Medium levels suggest a neutral attitude and low levels suggest a negative attitude and pessimism.

References

- Liutsko, L.; Malova, Y.V.; Poddubnij, S.E.; Rozhkova, N.I.; Maldonado, J.G. Proprioceptive Indicators of Stress Resistance. Personality and Individual Differences 2016, 101, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søvold, L.E.; Naslund, J.A.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Saxena, S.; Qoronfleh, M.W.; Grobler, C.; Münter, L. Prioritizing the Mental Health and Well-Being of Healthcare Workers: An Urgent Global Public Health Priority. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.X.; Lamers, F.; de Geus, E.J.C.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Differential Autonomic Nervous System Reactivity in Depression and Anxiety During Stress Depending on Type of Stressor. Psychosom Med 2016, 78, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holahan, C.J.; Moos, R.H. Life Stress and Health: Personality, Coping, and Family Support in Stress Resistance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1985, 49, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, G.; Dorn, L. Cognitive and Attentional Processes in Personality and Intelligence. In International Handbook of Personality and Intelligence; Saklofske, D.H., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Perspectives on Individual Differences; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1995; pp. 367–396. ISBN 978-1-4757-5571-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liutsko, L. AGE AND SEX DIFFERENCES IN PROPRIOCEPTION BASED ON FINE MOTOR BEHAVIOUR. 235.

- Mira y López, E.M. K.P.: Myokinetic Psychodiagnosis; M.K.P.: Myokinetic psychodiagnosis; Logos Press: Oxford, England, 1958; pp. xx, 186. [Google Scholar]

- Şenol, D.; Uçar, C.; Çay, M.; Özbağ, D.; Canbolat, M.; Yıldız, S. The Effect of Stress-Induced Cortisol Increase on the Sense of Ankle Proprioception. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil 2019, 65, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liutsko, L.; Tous, J.M.; Segura, S. The Effects of Dual Task (Fine Motor Precision + Cognitive Charge) on Proprioception. Journal of Education Culture and Society 2014, 5, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, H.; Donkelaar, P.V.; Cole, J.; Vercher, J.-L.; Gauthier, G.; Miall, R. The Role of Proprioception and Attention in a Visuomotor Adaptation Task. Experimental Brain Research 2000, 132, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liutsko, L.; Muiños, R.; Tous-Ral, J.M. Age-Related Differences in Proprioceptive and Visuo-Proprioceptive Function in Relation to Fine Motor Behaviour. Eur J Ageing 2014, 11, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gironell, A.; Luitsko, L.; Muiños Martínez, R.; Tous Ral, J.M. Differences Based on Fine Motor Behaviour in Parkinson’s Patients Compared to an Age Matched Control Group in Proprioceptive and Visuo-Proprioceptive Test Conditions. 2012.

- Efremov, V.S.; Sluchaevskiĭ, F.I.; Popov, A.G.; Rozenfel’d, E.N.; Dunaevskaia, V.O. [Functional motor asymmetries in various mental disorders (according to the results of a psychodiagnostic myokinetic test). Zh Nevropatol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 1982, 82, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Liutsko, L.; Iglesias, T.; Tous Ral, J.M.; Veraksa, A. Proprioceptive Indicators of Personality and Individual Differences in Behavior in Children With ADHD. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, T.; Liutsko, L.; Tous, J.M. Proprioceptive Diagnostics in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Psicothema 2014, 26, 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.B.; Housley, S.N.; Flores, A.M.; Cope, T.C.; Perreault, E.J. Cancer Survivors Post-Chemotherapy Exhibit Unique Proprioceptive Deficits in Proximal Limbs. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2022, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housley, S.N.; Nardelli, P.; Carrasco, D.I.; Rotterman, T.M.; Pfahl, E.; Matyunina, L.V.; McDonald, J.F.; Cope, T.C. Cancer Exacerbates Chemotherapy-Induced Sensory Neuropathy. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 2940–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Housley, S.N.; Nardelli, P.; Rotterman, T.M.; Cope, T.C. Neural Circuit Mechanisms of Sensorimotor Disability in Cancer Treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118, e2100428118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monfort, S.M.; Pan, X.; Loprinzi, C.L.; Lustberg, M.B.; Chaudhari, A.M.W. Impaired Postural Control and Altered Sensory Organization During Quiet Stance Following Neurotoxic Chemotherapy: A Preliminary Study. Integr Cancer Ther 2019, 18, 1534735419828823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CHYKHANTSOVA, O.; KUPRIEIEVA, O. Possibilities of Positive Psychotherapy in the Formation of Hardiness. “The Global Psychotherapist”, Vol. 1, No. 2. 2021. Available online: https://www.positum.org/ppt_artticles/chykhantsova-o-kuprieieva-o-raisch-s-2021-possibilities-of-positive-psychotherapy-in-the-formation-of-hardiness-the-global-psychotherapist-vol-1-no-2-pp-22-26/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Han, J.; Anson, J.; Waddington, G.; Adams, R.; Liu, Y. The Role of Ankle Proprioception for Balance Control in Relation to Sports Performance and Injury. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 842804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.-C.; Li, C.-I.; Tseng, C.-H.; Lin, K.-S.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsia, T.-C.; Lee, Y.-D.; Lin, C.-C. Quality of Life Predicts Survival in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golzy, M.; Rosen, G.H.; Kruse, R.L.; Hooshmand, K.; Mehr, D.R.; Murray, K.S. Holistic Assessment of Quality of Life Predicts Survival in Older Patients with Bladder Cancer. Urology 2023, 174, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maisey, N.R.; Norman, A.; Watson, M.; Allen, M.J.; Hill, M.E.; Cunningham, D. Baseline Quality of Life Predicts Survival in Patients with Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Eur J Cancer 2002, 38, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficace, F.; Innominato, P.F.; Bjarnason, G.; Coens, C.; Humblet, Y.; Tumolo, S.; Genet, D.; Tampellini, M.; Bottomley, A.; Garufi, C.; et al. Validation of Patient’s Self-Reported Social Functioning as an Independent Prognostic Factor for Survival in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: Results of an International Study by the Chronotherapy Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 2020–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Cho, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Hong, J.; Nam, E.; Park, J.; Cho, E.K.; Shin, D.B.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, W.K. Self-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life Predicts Survival for Patients with Advanced Gastric Cancer Treated with First-Line Chemotherapy. Qual Life Res 2008, 17, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheard, M.; Golby, J. Personality Hardiness Differentiates Elite-level Sport Performers. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2010, 8, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhad, M.A.S.; Besharat, M.A. Relations of Resilience and Hardiness with Sport Achievement and Mental Health in a Sample of Athletes. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2010, 5, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzi, S.; Besharat, M.A. The Impact of Hardiness on Sport Achievement and Mental Health. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2010, 5, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, S.R. The Personality Construct of Hardiness: I. Effects on Experiencing, Coping, and Strain. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 1999, 51, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assumptive Worlds and the Stress of Traumatic Events: Applications of the Schema Construct | Social Cognition. Available online: https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/soco.1989.7.2.113 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Tous-Ral, J.M.; Muiños, R.; Liutsko, L.; Forero, C.G. Effects of Sensory Information, Movement Direction, and Hand Use on Fine Motor Precision. Percept Mot Skills 2012, 115, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous, J.M.; Viadé, A.; Muiños, R. Validez estructural de los lineogramas del psicodiagnóstico mio kinético, revisado y digitalizado (PMK-RD). PST 2007, 350–356. [Google Scholar]

- Tous Ral, J.M.; Liutsko, L. Human Errors: Their Psychophysical Bases and the Proprioceptive Diagnosis of Temperament and Character (DP-TC) as a Tool for Measuring. Psych. Rus 2014, 7, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muiños Martinez, R. Psicodiagnóstico miokinético: desarrollo, descripción y análisis factorial confirmatorio, El. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, 2008.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).