Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

04 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

| Contents |

- Chapter 1 - Introduction ……………………….……………. page 1

- Chapter 2 - Review……………………………….……………. page 5

- Chapter 3 - Incompleteness…………………………………. page 10

- Chapter 4 - Restructure of “EIA” ……………………………page 24

- Chapter 5: Skeletal reference Charts for ‘EIA’ process...page 33

- Figure 1: UK agricultural legislation controls reference chart

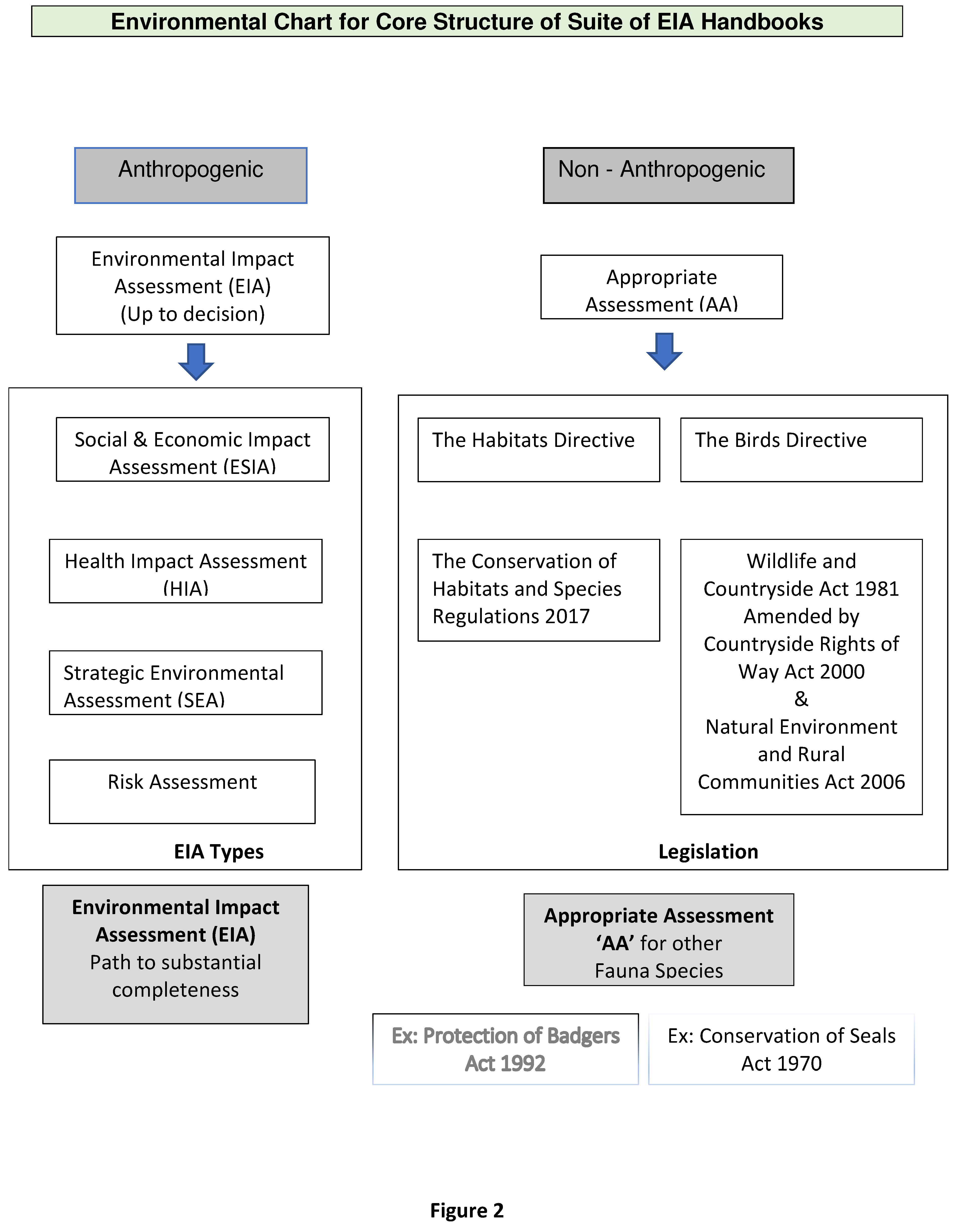

- Figure 2: Environmental Chart for Structure of ‘Suite of EIA Handbooks’

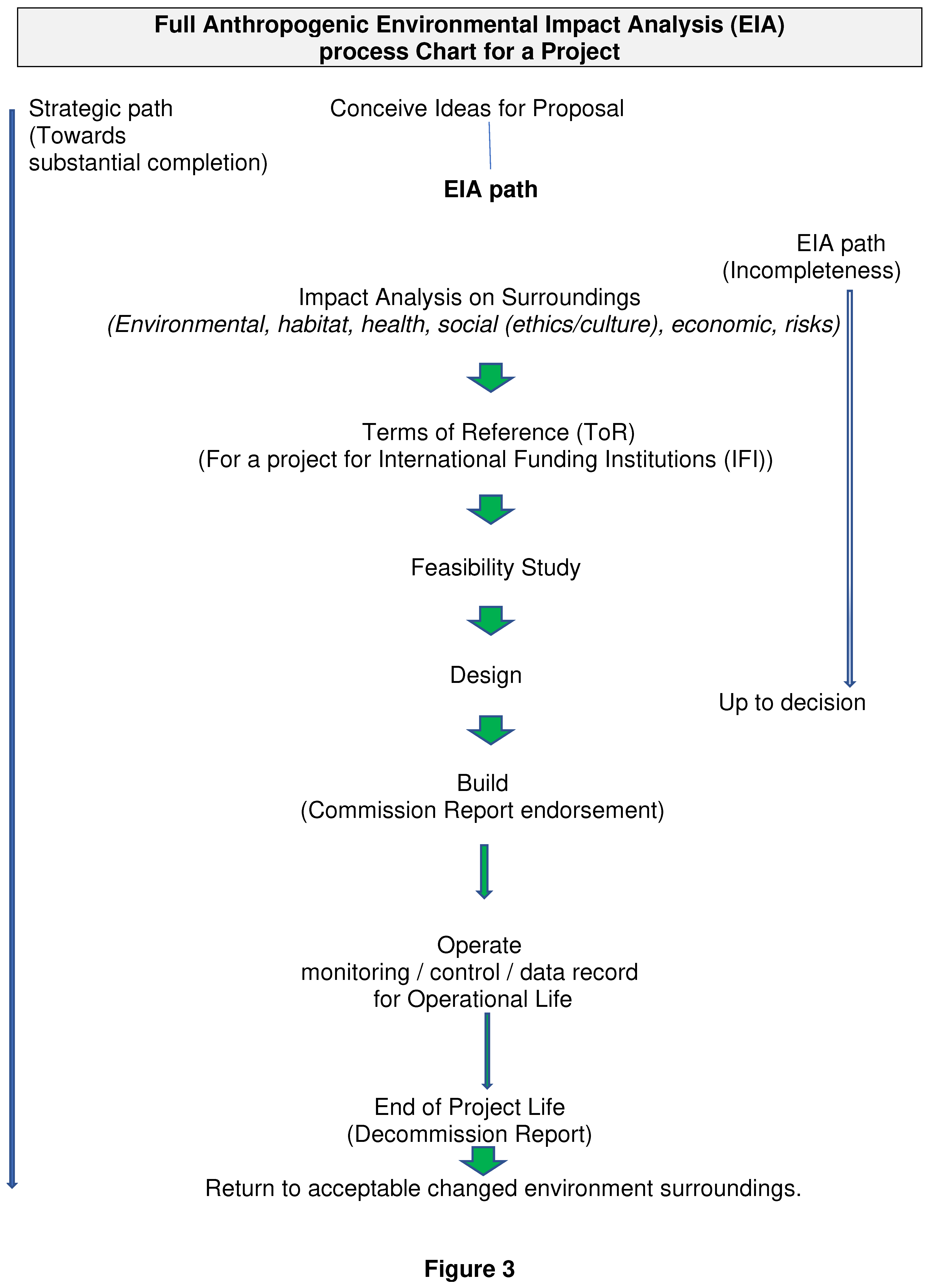

- Figure 3: Full Anthropogenic Environmental Impact Analysis -Chart for a Project

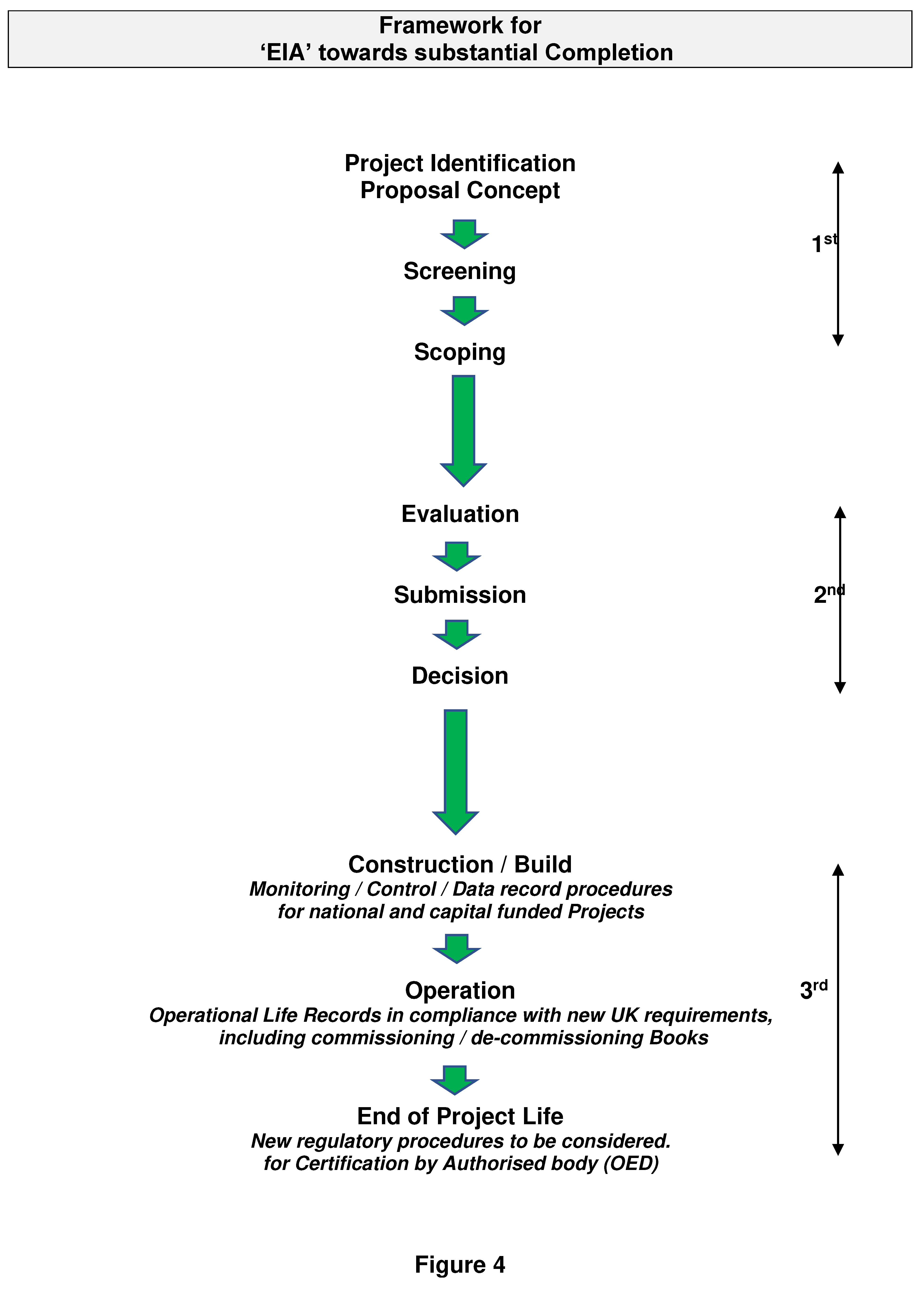

- Figure 4: Framework for ‘EIA’ towards substantial Completion

- Chapter 6 - Conclusions………………………………………page 37

- Bibliography

Chapter 1 - Introduction

1.1. Introduction:

1.2. Brexit legislation, and an opportunity for a ‘National Environmental Structure Plan Framework Model’ towards future UK Environmental Legislation

Chapter 2 - Review

2. A summary Review of various operating international EIA Processes

Chapter 3 - ‘Incompleteness’

3. Incompleteness of the EIA process

3.2. EIA process continuation to end of project life/return to acceptable environmental conditions

3.2.1). Air Pollution:

3.2.2). Climate Change

3.2.3). Renewable Energy:

3.2.4). Water Pollution

3.2.5). Waste:

3.3. Approach towards an effective structure for ‘EIA’ after Brexit

3.4. UK and International Cases embracing Project Reviews

- Should construction of part of a project be modified and allowed to proceed without contractual verification? Under FIDIC procedures, Contract Law’s structured approach is unlikely to permit such action.

- Did the ICJ take the correct approach130 and could the Court have pronounced on the ‘principle of continuity’131 to allow automatic succession of the Treaty? Was it contractually correcting for the 1977 Treaty ever to have been in force132? The ICJ was asked to determine the legal consequences arising from its consequences.133

Chapter 4 - Restructure of the Environmental Impact Process

4.0. Environmental Impact Assessment Structure Review, following Brexit

4.01. Clarification for terms used and adopted in this Paper:

4.2. Existing Environmental Regulations for restructure process

4.3. New identified Environmental Regulations under a restructured process

| Table 1 |

|

|

Table 2 Records and procedures during construction Works and Operational Life: |

|

|

Table 3 New Part: Procedures for Decommissioning and End of Project Life |

|

|

Table 4 New Part: Procedures for climate change requirements. |

|

Table 5 Schedule 5: Decommissioning, ‘end of project life and return to environmental footprint’. |

Characteristics of the demolition and removal of materials.

|

Chapter 5 - Skeletal reference Charts for ‘EIA’ structured process

Conclusions

Recommendations:

| BIBLIOGRAPHY |

| Table of Cases: |

- MOX Plant Case (Ireland v UK) 2002

- New Zealand v France [1974] ICJ Rep 457

- Trail Smelter Arbitration (United States and Canada, 16 April 1938, 3 RIAA 1907(1941)

- ‘Regina v Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council, Ex parte Milne (2): QBD 31 Jul 2000’

- ‘R. v. Rochdale MBC, ex parte Tew and Others

- EU v Ireland (C-50/09) [2011] Env LR 25

- C-461/13 Bund fur Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland, Advocate General Jaaskinen

- Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project (Hungary/Slovakia) ICJ Rep 7 (80)

- Pulp Mills of the River Uruguay Case (Argentina v Uruguay) [2006] ICJ

- Lac Lanoux Arbitration (France v Spain) (1975) 24 ILR 101

- Kraaijeveld BV v Zuid-Holland (1996) C-72/95

| Table of Legislation: |

- The Town and Country Planning and Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Amendment) Regulations 2018, UK Statutory Instruments, 2018, No 695

- The Council of the European Communities, June 1985, on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment, 85/337/EEC

- European Communities Act 1972, UK Public General Acts, 1972 c. 68

- European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, UK Public General Acts, 2018 c. 16

- The Environment Act 2021 (Commencement No. 1) Regulations 2021, UK Statutory Instruments, 2021 No. 1274

- Environment Bill 2020 policy statement - Gov.UK, 2. Environmental Governance, para 3, line 1, 4

- Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 1992, in force 1995

- Impact Assessment Act (S.C. 2019, C. S. 1), Government of Canada

- Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), Government of India, 27 January 1994

- India’s Environment Protection Act 1986; Indian Constitution

- Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, Ministry of Environment and forests, Notification, New Delhi, 27th January 1994

- National Environmental Policy Act, United States of America, in force 1st January 1970

- EIA Directive (85/337/EEC)

- Environmental Protection Act 1990, UK Public General Acts, 1990 c. 43

- Pollution Prevention and Control Act 1999

- The England Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2016, UK Statutory Instruments, 2016, No. 1154

- Clean Air Act 1993, UK Public General Acts, 1993, c 11

- Environment Act 1995, UK Public General Acts, 1995 c 25

- Climate Change Act 2008, UK Public General Acts, 2008, c 27

- Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and the Council establishing a framework for the Community action in the field of water policy 23 October 2000, L327/1; EU Water Framework Directive (WFD)

- Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2003, SI 2003 No. 3242

- Nitrate Pollution Prevention (Amendment)(No.2) Regulations 2016 (SI No. 1254)

- Reduction and Prevention of Agricultural Diffuse Pollution (England) Regulations 2018 (SI 2018 No. 151)

- Floods and Water (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (SI 2019 No. 558)

- Controlled Waste (Registration of Carriers and Seizure of Vehicles) Regulations 1991, UK Statutory Instruments, 1991, No. 1624

- Hazardous Waste Regulations 2005, UK Statutory Instruments, 2005, No. 894

- Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2010, UK Statutory Instruments, ISBN 978-0-11-149142

- Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and the Council, 19 November 2008, on waste and repealing certain Directives.

- The Waste (England and Wales) Regulations 2011, UK Statutory Instruments, 2011 No. 988

- Budapest Treaty of 16 September 1977 between Hungary/ Czechoslovakia on the Construction and Operation of the Gabčíkovo- Nagymaros Barrage System.

- Uruguay and Argentina, Statute of the River Uruguay. Signed at Salto in February 1975, No. 21425

- THE RIVER URUGUAY EXECUTIVE COMMISSION COMISIÓN ADMINISTRADORA DEL RIO URUGUAY, C.A.R.U

- Susan Wolf and Neil Stanley, Wolf and Stanley on Environmental Law, sixth edition 2016, published by Routledge.

- The Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017, UK Statutory Instruments 2017 No. 571

- The Town and Country Planning and Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Amendment) Regulations 2018, Statutory Instruments, No. 695

- The EIA Regulations: Two Years On, 16 May 2019, https://npaconsult.co.uk/article-type/environmental-design/>,

- The Environmental Impact Assessment (Amendment) (Northern Ireland) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (revoked), UK Statutory Instruments 2019 No 123

| Bibliography: |

- Barr B, and Grutters L, Institution of Civil Engineers, FIDIC User’s Guide, Third Edition, Thomas Telford Ltd.

- Bartlett R, (1988) SYMPOSIUM: POLICY AND IMPACT ASSESSMENT, Impact Assessment

- Boyle S, The Case for Regulation of Agricultural Water Pollution

- British Energy Security Strategy, HM Government, April 2022

- Caldwell L, (1988) Environmental Impact Analysis (EIA): Origins, Evolution, and Future Directions, Impact Assessment

- Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary context United Nations 1991, a United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, signed in Espoo, Finland in 1991, in force in 1997.

- Council Directive 92/43/EEC, 21 May 1992, on the Conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora, Official Journal of the European Communities, No L 206/7

- Craik N, The International Law of Environmental Impact Assessment, Process, Substance and Integration, 2010

- Cross-Compliance under the Common Agricultural Policy: A possible mechanism for stronger standards

- Department of Environment food and rural affairs (defra), Code of Good Agriculture Practice, 1st published 2009 ISBN 978 0 11 243284

- Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, ‘Air Pollution in the UK 2019’ published September 2020.

- Directive 2011/92/EU of European Parliament and the Council, 13 December 2011, on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment (codification).

- Ecojustice Blog, breaking down Canada’s Impact Assessment Act, posted December 7, 2021

- EIA (https://www.cseindia.org/page/eia) > Story, 3 History of EIA in India

- Environmental Impact Assessment Draft Notification 2020, India: A Critique

- Environmental Impact Assessment Systems in Europe and Central Asia Countries, May 2002

- Europe and Central Asia Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Department (World Bank)

- European Commission, Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services, Indicators for ecosystem assessments

- European Commission, Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services, Indicators for ecosystem assessments and their services, 2nd Report - Final 2014

- Fethiye Municipality; ‘Project Completion Report’ ‘Wastewater Collection and Treatment Facilities for Fethiye’, February 2004, archived.

- FIDIC Conditions of Contract for Plant and Design-Build, 1st Edition 1999, ISBN 2-88432-023-07

- FIDIC EPC/Turnkey Projects, 1st Edition 1999, ISBN 2-88432-021-0

- General Contract Conditions of Contract, produced by the UK Institution of Civil Engineers

- Glasson j and Therivel R, Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment, 5th Edition

- Hindle R, Johnstone D, Kempton R, Morgan J, Institution of Civil Engineers, Proceedings, Part 1, Design and Construction, December 1989, Volume 86, Salford docks urban renewal: design, construction and management of civil engineering works.

- HM Government, A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment, 2018

- House of Commons Library, Briefing Paper, Number 7793, 2 May 2017, Legislating for Brexit: The Great Repeal Bill

- Hughes D Jewell T, Lowther J, Parpworth N, Prez P, Environmental Law, 4th edition.

- International Court of Justice, Press Release (Unofficial), No. 2017/31, dated 21 July 2017

- International Court of Justice, Press Release, No 2010/10, 20 April 2010

- International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS)

- Legal vacuum and the Bhopal Gas tragedy, 10 June 2010, PRS Legislative Research

- Lely the Minister of Waterstaat, which is the department for the maintenance of Dikes, roads, bridges, canals, etc.

- Nagy B, The ICJ Judgement in the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project Case and its Aftermath

- National Geographic, Learn with us. The Coriolis Effect: Earth’s Rotation and Its Effects on Weather.

- Net Zero, The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming, Committee on Climate Change, May 2019

- Noumea Convention 1986

- PAS 2080:2016, British Standard Institute Publicly Available Specification.

- Process Guidance Note 6/9 (04), Crown copyright 2004, defra, Scottish Executive, Welsh Assembly Government; (BATNEEC)

- Protocol on Strategic Environmental Assessment in 2003, in force in 2011

- Sands P and Peel J with Fabra A and Mackenzie R, Principles of International Environmental Law, fourth edition.

- Stockholm Earth Summit, 1972

- TECO Group web page; https://tecogrp.com/wadi-arab-waste-water-treatment-plant/

- The Hague Justice Portal, Dr. Panos Merkouris, ‘Case concerning Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay: Of Environmental Impacts Assessments and Phantom Experts’

- The International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) https://fidic.org>

- The Netherlands’ Zuiderzee - Project - WUR depot

- The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, in force 1998

- The Treaty on European Union, signed in Maastricht, 7th February 1992, in force 1 November 1993

- Tromans S QC, Environmental Impact Assessment, 2nd Edition, Bloomsbury Professional Ltd 2012

- UN, Convention on Biological Diversity, 1992

- UNFCCC, Convention of Biodiversity, Earth Summit, Rio de Janeiro, 5 June 1992

- UNFCCC, The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, June 1992

- UNFCCC, United Nations, FCCC/INFORMAL/84, GE.05-622200 (E) 200705

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 3-14 June 1992, Annex I, Rio Declaration on Environment and Development

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 10 December 1982, Section 4, Monitoring and Environmental Assessment

- Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties, 23 August 1978

- Weather, Government Webpage, Flight Environment, Prevailing Winds, Hemispheric Prevailing Winds

- White K, E. Bellinger, Saul A, Symes M and Hendry K, Urban Waterside Regeneration, problems and prospects

- World Charter for Nature, United Nations, A/RES/37/7, General Assembly 28 October.

| 1 | Robert V Bartlett (1988) SYMPOSIUM: POLICY AND IMPACT ASSESSMENT, Impact Assessment, 6:3-4, 73-74, DOI: 10.1080/07349165.1988.9725647, line 1, 73 |

| 2 | Bartlett R, n2, para 3, line 2, 73 |

| 3 | Lynton K. Caldwell (1988) Environmental Impact Analysis (EIA): Origins, Evolution, and Future Directions, Impact Assessment, 6:3-4, 75-83, DOI: 10.1080/07349165.1988.9725648, 2nd para, 75 |

| 4 | Caldwell K, n4, A Learning process, para 1, 79 |

| 5 | ibid, concluding sentence, p 83 |

| 6 | The Council of the European Communities, June 1985, on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment, 85/337/EEC, para 6,” Whereas the disparities……to Article 100 of the Treaty”

|

| 7 | The Town and Country Planning and Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Amendment) Regulations 2018, UK Statutory Instruments, 2018, No 695, Explanatory Note, insert new regulations 33A and 33B into SI 2017/571 |

| 8 | House of Commons Library, Briefing Paper, Number 7793, 2 May 2017, Legislating for Brexit: The Great Repeal Bill |

| 9 | European Communities Act 1972, UK Public General Acts, 1972 c. 68 |

| 10 | Ref: Miller (No 1) Case - Supreme Court decision: may not be used to nullify rights that Parliament enacted through primary legislation - Prime Minister’s right.

|

| 11 | The Treaty on European Union, signed in Maastricht, 7th February 1992, in force 1 November 1993 |

| 12 | European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, UK Public General Acts, 2018 c. 16 |

| 13 | HM Government, A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment, 2018 |

| 14 | The Environment Act 2021 (Commencement No. 1) Regulations 2021, UK Statutory Instruments, 2021 No. 1274 |

| 15 | Environment Bill 2020 policy statement - Gov.UK, 2. Environmental Governance, para 3, line 1, 4 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/environment-bill-2020/30-january-2020-environment-bill-2020-policy-statement//contents

|

| 16 | Environment Bill 2020 policy statement - Gov.UK, 2. Environmental Governance, last para, penultimate line, 4; EA 2021, Part I, Chapter 1, Environmental Improvement Plans, s10 (4) |

| 17 | Environment Act 2021, UK Public General Acts, 2021 c 30, Part I Environmental Governance, Chapter 2, The Office for Environmental Protection, ss 22 - 43. https://www.theoep.org.uk/office-environmental-protection

|

| 18 | EA 2021, s 39 (1)(a)(b), Judicial review: powers in urgent cases and to intervene. |

| 19 | EA 2021, PART 1 Chapter 1, Section 17, Policy statement on environmental principles, 17 (1)(2)(3)(4)(5) |

| 20 | EA 2021, PART 1 Chapter 2, s 28-30 and 31-36 |

| 21 | Stockholm Earth Summit, 1972, Principles 14 and 15 |

| 22 | United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, 3-14 June 1992, Annex I, Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, Principle 17 |

| 23 | Ibid, Annex II, Agenda 21 |

| 24 | The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, in force 1998, 27 No. Articles, Article 8 - Environmental Impact Assessment. https://www.ats.aq/e/protocol.html

|

| 25 | ibid, Article 8 - Environmental Impact Assessment. |

| 26 | Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary context United Nations 1991, a United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, signed in Espoo, Finland in 1991, in force in 1997; Conference was supplemented by the Protocol on Strategic Environmental Assessment in 2003, in force in 2011. |

| 27 | World Charter for Nature, United Nations, A/RES/37/7, General Assembly 28 October 2003, 11 Functions, 11 |

| 28 | Ibid, 11(b)(c) |

| 29 | United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 10 December 1982, Section 4, Monitoring and Environmental Assessment, Articles 205, 206 |

| 30 | Noumea Convention 1986, Article 16 |

| 31 | International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), created by mandate of United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea. (UNCLOS) |

| 32 | Neil Craik, The International Law of Environmental Impact Assessment, Process, Substance and Integration, 2010, para 2 137 |

| 33 | UNFCCC, Convention of Biodiversity, Earth Summit, Rio de Janeiro, 5 June 1992, in force December 1993. |

| 34 | Philippe Sands and Jacqueline Peel with Adrianna Fabra and Ruth Mackenzie, Principles of International Environmental Law, fourth edition, 1992 Biodiversity Convention, first sentence 673, |

| 35 | UN, Convention on Biological Diversity, 1992, Article 14, Impact Assessment and Minimizing Adverse Impacts, 1(a) |

| 36 | ibid, Article 7, Identification and monitoring, (a)(b)(c)(d) |

| 37 | Phillippe Sands et al, Part III, 14, Impact Environmental Assessment, World Bank and other multilateral lending institutions 675 |

| 38 | Europe and Central Asia Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Department (World Bank) |

| 39 | Environmental Impact Assessment Systems in Europe and Central Asia Countries, May 2002, Chapter 6. Conclusions and recommendations, 6.1 para 1, last 4 lines 34 http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website00983A/WEB/PDF/EIA_IN_E.PDF

|

| 40 | Neil Craik, The International Law of Environmental Impact Assessment, Process Substance and Integration, Cambridge University Press, paperback 2010, Part II Background norms, 2.1 Introduction, para 1, lines 6-8 23 |

| 41 | Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 1992, in force 1995 |

| 42 | Impact Assessment Act (S.C. 2019, C. S. 1), Government of Canada, Justice Laws Website |

| 43 | Ecojustice Blog, breaking down Canada’s Impact Assessment Act, posted December 7, 2021, https://ecojustice.ca/category/special.update

|

| 44 | Article - environmental impact assessment, EIA Process; https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca, |

| 45 | Ecojustice Blog, breaking down Canada’s Impact Assessment Act, where did the IAA come from? lines 6-7 |

| 46 | Neil Craig, The International Law of EIA, 207 - 208 |

| 47 | Neil Craig, The International Law of EIA, 2nd para, 2nd sentence, fn28 32. |

| 48 | Neil Craig, The International Law of EIA, lines 3-4 105 |

| 49 | Neil Craig, The International Law of EIA, 130 |

| 50 | Ibid, fn 184 131 |

| 51 | Neil Craig, The International Law of EIA, fn 96 201 |

| 52 | Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), Government of India, 27 January 1994, https://www.cseindia.org/understanding-eia-383

|

| 53 | India’s Environment Protection Act 1986; Indian Constitution Article 48(a) and 51(A)g. |

| 54 | EIA (https://www.cseindia.org/page/eia) > Story, 3 History of EIA in India, para2 |

| 55 | Legal vacuum and the Bhopal Gas tragedy, 10 June 2010, PRS Legislative Research; reference: change started https://changestarted.com/indias-environment-impact-assessment-eia-2020-amendments-and-contentions/

|

| 56 | Act No. 29 of 1986, Government of India. |

| 57 | Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, Ministry of Environment and forests, Notification, New Delhi, 27th January 1994 (Incorporating the amendments) |

| 58 | n53, https://www.cseindia.org/understanding-eia-383, 5. Forms of impact assessment, para 3 |

| 59 | Environmental Impact Assessment Draft Notification 2020, India: A Critique |

| 60 | National Environmental Policy Act, United States of America, in force 1st January 1970 |

| 61 | EIA Directive (85/337/EEC) |

| 62 | Earth Summits 1972, 1992 |

| 63 | Stuart Bell, Donald McGillvray, Ole W. Pedersen, Emma Lees, Elen Stokes, Environmental Law, 9th Edition, The Importance of Definitions 7 |

| 64 | European Commission, Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services, Indicators for ecosystem assessments under Action 5 of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 |

| 65 | Ex: Greater Irbid Wastewater Project, Jordan, Project Completion Report, Volume One, June 2001, Contract 174/95, completed May 1999, ‘Tests on Completion’ Structure Plan. / Ex: Wastewater Collection and Treatment Facilities for Fethiye, Turkey, Project Completion Report, February 2004, Tests on Completion Structure Plan - FESKI Municipality, Fethiye, Turkey / German Funding (archived) |

| 66 | Clean Air Act 1993, UK Public General Acts, 1993, c 11 |

| 67 | Environment Act 2021, UK Public General Acts, 2021 c 30, PART 4 Air quality and environmental recall s72 - schedule 11 - local air quality framework & s73 schedule 12 - smoke control in E&W |

| 68 | David Hughes, Tim Jewell, Jason Lowther, Neil Parpworth, Paula de Prez, fourth edition, Further issues in atmospheric pollution, 548 |

| 69 | Process Guidance Note 6/9 (04), Crown copyright 2004, defra, Scottish Executive, Welsh Assembly Government; (BATNEEC) |

| 70 | Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, ‘Air Pollution in the UK 2019’ published September 2020. |

| 71 | Ibid, 1 Introduction, para 3; Directive 2008/50/EC; Fourth Daughter Directive (2004/107/EC) reference endnote 2. |

| 72 | Weather, Government Webpage, Flight Environment, Prevailing Winds, Hemispheric Prevailing Winds. https://www.weather.gov/source/zhu/ZHU_Training_Page/winds/Wx_Terms/Flight_Environment.htm#:~:text=The%20pressure%20gradient%20causes%20the,flow%20parallel%20to%20the%20isobars. |

| 73 | National Geographic, Learn with us. The Coriolis Effect: Earth’s Rotation and Its Effects on Weather https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/coriolis-effect/

|

| 74 | UNFCCC, The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, June 1992, Principle 7 |

| 75 | Climate Change Act 2008, UK Public General Acts, 2008, c 27 |

| 76 | ibid, Part 1, Carbon Budgeting, regs, 4-10 |

| 77 | ibid, Part 2, The Committee on Climate Change, regs (32((33)(34)(35)(36)(37)(38)(39)(40)(41)(42) (43). |

| 78 | ibid, Part 1, Carbon Targeting and budgeting, The target for 2050, s1 |

| 79 | ibid, Part 6, General supplementary provisions, regs (89)(90)(91)(92)(93)(94)(95)(96)(97)(98)(99) (100) (101) |

| 80 | PAS 2080:2016, British Standard Institute Publicly Available Specification, Carbon Management in infrastructure, Construction Leadership Council, The Green Construction Board, 31 May 2016 |

| 81 | Ibid, 1 Scope, Table 1, The scope of PAS 2080 |

| 82 | Ibid, 1 Scope, lines 1-2 |

| 83 | Ibid, 3.17 greenhouse gases (GHGs), NOTE 2. |

| 84 | ibid, 7 Quantification of GHG emissions, 7.1.4 Study period. |

| 85 | ibid, 0 Introduction, 0.1 Infrastructure and greenhouse gas emissions, Figure 1, [figures extrapolated from chart]; CO2e means Carbon Dioxide equivalent,

|

| 86 | Ibid, 3.7 carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e); [BS ISO 14064-1]: 2006; pas 2050: 2011] |

| 87 | Ibid,3.16 global warming potential (GWP); BS ISO 14084-1: 2006 |

| 88 | Net Zero, The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming, Committee on Climate Change, May 2019. |

| 89 | Environment Act 2021, UK Public General Acts, 2021, c 30, Chapter 2, The Office for Environmental Protection, s 22 - 43 |

| 90 | ibid, Reg. 17(1)(2)(3)(4)(a)(b)(5)(a)(b)(c)(d)(e) |

| 91 | UNFCCC, United Nations, FCCC/INFORMAL/84, GE.05-622200 (E) 200705 |

| 92 | British Energy Security Strategy, HM Government, April 2022 |

| 93 | British Energy Security Strategy, Renewables, pages 16-23 |

| 94 | British Energy Security Strategy, Renewables, page 21, advanced new small modular Reactors (SMRs) (AMRs) |

| 95 | European Commission, Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services, Indicators for ecosystem assessments and their services, 2nd Report - Final 2014 |

| 96 | Examples: Severn Estuary Barrage / Mersey Estuary Tidal Project-Liverpool Bay Lagoons / Swanage Bay Tidal Lagoon |

| 97 | “Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and the Council establishing a framework for the Community action in the field of water policy” 23 October 2000, L327/1; EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) |

| 98 | Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2003, SI 2003 No. 3242 |

| 99 | Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017, SI 2017, No. 407 |

| 100 | Sam Boyle, The Case for Regulation of Agricultural Water Pollution, Performance standards under the Water Framework Directive, lines 1-2 7 |

| 101 | Stuart Bell et al, p 627, para 2, line 6. |

| 102 | Department of Environment food and rural affairs (defra), Code of Good Agriculture Practice, 1st published 2009 ISBN 978 0 11 243284 5 |

| 103 | Stuart Bell et al, The Water Framework Directive, CONSIDER THIS 626 |

| 104 | n 96, Part 6, ss 26-33 |

| 105 | Implementation of the Nitrates Directive in England, 7th Report 2007-8, from Council Directive 91/676/EEC (OJ L375, 31.12.1991, P1) |

| 106 | The Nitrate Pollution Prevention Regulations 2008 No. 2349 |

| 107 | The Protection of Waters against Pollution from Agriculture - Consultation on Implementation of the Nitrates Directive (Dec’ 2011) |

| 108 | Nitrate Pollution Prevention (Amendment)(No.2) Regulations 2016 (SI No. 1254) |

| 109 | Reduction and Prevention of Agricultural Diffuse Pollution (England) Regulations 2018 (SI 2018 No. 151) |

| 110 | Floods and Water (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (SI 2019 No. 558) |

| 111 | Ref. Chapter 5 - Skeletal reference Charts for EIA structured process, UK agricultural legislation controls reference chart, 34. |

| 112 | Cross-Compliance under the Common Agricultural Policy: A possible mechanism for stronger standards |

| 113 | Environmental Protection Act 1990, UK Public General Acts - 1990 c 43 |

| 114 | ibid, reg 75(4) |

| 115 | Environmental Act 1995, UK Public General Acts, 1995 c. 25 |

| 116 | Controlled Waste (Registration of Carriers and Seizure of Vehicles) Regulations 1991, UK Statutory Instruments, 1991, No. 1624 |

| 117 | Hazardous Waste Regulations 2005, UK Statutory Instruments, 2005, No. 894 |

| 118 | Environmental Permitting (England and Wales) Regulations 2010, UK Statutory Instruments, ISBN 978-0-11-149142-3 |

| 119 | Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and the Council, 19 November 2008, on waste and repealing certain Directives. |

| 120 | ibid, article 3(1) |

| 121 | The Waste (England and Wales) Regulations 2011, UK Statutory Instruments, 2011 No. 988 |

| 122 | David Hughes et al, Environmental Law, 4th edition, Chapter 2, The ethical basis of environmental law and its principles, lines 1-2 17 |

| 123 | Stuart Bell et al, Environmental Law, 9th Edition, Town and Country Planning as a tool to environmental policy, 3rd para, line1 400 |

| 124 | Stephen Tromans QC, Environmental Impact Assessment, 2nd Edition, Chapter 9, Conservation and Habitats law in the EIA context, 9.1 lines 1-2 345 |

| 125 | Council Directive 92/43/EEC, 21 May 1992, on the Conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora, Official Journal of the European Communities, No L 206/7 |

| 126 | The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, Document, annex I (EIA) |

| 127 | International Court of Justice, Press Release (Unofficial), No. 2017/31, dated 21 July 2017 |

| 128 | Budapest Treaty of 16 September 1977 between Hungary/ Czechoslovakia on the Construction and Operation of the Gabčíkovo- Nagymaros Barrage System. |

| 129 | Hungary/Slovakia Treaty of 1997 - Gabčikovo-Nagymaros Project |

| 130 | Bolddizsar Nagy, The ICJ Judgement in the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project Case and its Aftermath: Success or Failure? 5 |

| 131 | Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties, 23 August 1978, Article 12 Other territorial regimes 2 (a)(b) |

| 132 | Bolddizsar Nagy, fn12 5 |

| 133 | Philippe Sands et al, Case concerning the Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project, 2nd para, lines 7-8 346 |

| 134 | Ibid, end 1st para 350 |

| 135 | Ibid, para 1 351 |

| 136 | Uruguay and Argentina, Statute of the River Uruguay. Signed at Salto in February 1975, No. 21425 |

| 137 | Philippe Sands et al, The Case Concerning Pulp Mills on the Uruguay River, 351-356 |

| 138 | Article 60, Any dispute concerning the interpretation or application of the Treaty and the Statute which cannot be settled by direct negotiations may be submitted by either Party to the ICJ |

| 139 | Philippe Sands et al, 1st para, last line 352 |

| 140 | ibid, 3rd para, line 7 352 |

| 141 | Ibid, para 2, line 21, fn 131 354 |

| 142 | Ibid, The Case Concerning Pulp Mills on the Uruguay River, last para, 1st sentence 355. |

| 143 | The Hague Justice Portal, Dr. Panos Merkouris, ‘Case concerning Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay: Of Environmental Impacts Assessments and Phantom Experts’, I Introduction, page 2, last para, reference fn10 on Precautionary principle; http://haguejusticeportal.net/Docs/Commentaries%20PDF/Merkouris_Pulp%20Mills_EN.pdf |

| 144 | THE RIVER URUGUAY EXECUTIVE COMMISSION COMISIÓN ADMINISTRADORA DEL RIO URUGUAY, C.A.R.U., Chapter X, Pollution, article 41a), page 28 Ratified by Act No. 21.413 of the Argentine Republic dated September 9, 1976, and Act 14.S21 of the Oriental Republic of Uruguay dated May 20, 1975. |

| 145 | International Court of Justice, Press Release, no 2010/10, 20 April 2010, reference 1) ‘breach of procedural obligations under Articles 7 to 12 of the 1975 Statute of the River Uruguay and that the declaration by the Court of this breach constitutes appropriate satisfaction’. |

| 146 | Philippe Sands et al, Lac Lanoux Arbitration, line 1 341 |

| 147 | The Statute of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) counted on historical antecedents to be kept in mind, in respect of the Statute of its predecessor, the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ).; The PCIJ was created under the auspices of the League of Nations pursuant to Article 14 of the Covenant of the League of Nations |

| 148 | Philippe Sands et al, Lac Lanoux Arbitration, line 2 341 |

| 149 | Ibid, 342, 2nd para |

| 150 | Ibid, last para 342 |

| 151 | Stephen Tromans QC, Environmental Impact Assessment, 2nd Edition, Table of European Cases, 2.158, Aannemersbedrijf P.K. Kraaijeveld BV ea v Gedeputeerde Staten van Zuid-Holland C-72/95 ECR [1996] 1-05404, line 1 78 |

| 152 | Ibid, lines 4-5 |

| 153 | EIA Directive (85/337/EEC), Council Directive of 27 June 1985, on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment, (85/337//EEC), No L 175/40 Official Journal of the European Union, Article 4 (2) |

| 154 | Stephen Tromans QC, (c), lines1-2 79 |

| 155 | ibid, lines 4-5 79 |

| 156 | (85/337/EEC), ANNEX 1, Projects subjected to Articles 4 (1), Annex 1, projects subject to Article 4 (1) 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. |

| 157 | ‘The Netherlands’ Zuiderzee - Project - WUR depot’, Chapter 7, The Netherlands’ Zuiderzee- Project, 2nd para https://edepot.wur.nl/22570

|

| 158 | Lely the Minister of Waterstaat, which is the department for the maintenance of Dikes, roads, bridges, canals, etc. |

| 159 | Zuiderzeevereniging is a private association for the study and the promotion of the reclamation of the Zuiderzee. |

| 160 | Judgement of the Court, 24 October 1996, Judgement 1; https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=ecli:ECLI%3AEU%3AC%3A1996%3A404

|

| 161 | Ibid, judgement 18 |

| 162 | Ibid, 30 |

| 163 | Ibid, 31 |

| 164 | Ibid, refer to judgement s 26. |

| 165 | Ibid, judgement 24, 25 |

| 166 | Ref: Article by Don C Smith published 1 April 2018. fn. 1: George Pring and Catherine Pring, Environmental Courts and Tribunal: A Guide for Policy Makers (UN Environmental Programme 2016). |

| 167 | Susan Wolf and Neil Stanley, Wolf and Stanley on environmental law, 2.8, A specialist environmental court, lines 2-3 60 |

| 168 | B. R. Hindle, D. T. Johnstone, R.C. Kempton, J. H. Morgan, Institution of Civil Engineers, Proceedings, Part 1, Design and Construction, December 1989, Volume 86, Salford docks urban renewal: design, construction and management of civil engineering works 1067-1087 |

| 169 | Ibid, 1081-1087 |

| 170 | Editors K.N. White, E.G. Bellinger, A.J. Saul, M. Symes and K Hendry, Urban Waterside Regeneration, problems and prospects, 10.7 Funding, para (1.) 89. |

| 171 | Contract conditions produced by the UK Institution of Civil Engineers; https://civilengineeringx.com/project-managment/contract-conditions-produced-by-the-uk-institution-of-civil-engineers/

|

| 172 | French funded project: “Improvement/Refurbishing of Sewage Treatment Plant Phase-I, II, Rehabilitation of Sewage Treatment Plant Phase - III, and Construction of Sewage Treatment Plant Phase-IV, Islamabad, 2005 - 2007 (the Project) |

| 173 | Fethiye Municipality; ‘Project Completion Report’ ‘Wastewater Collection and Treatment Facilities for Fethiye’, February 2004, archived; important statistics: date of commencement ‘Lot 1 Contract’ 4 June 2002, original date of completion 29 January 2004, actual completion date 12 December 2003, |

| 174 | Reference: Fethiye Advanced Biological Wastewater Treatment Plant, 2nd Stage Units Application Project, Final Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/353601590561579771/text/Environmental-and-Social-Impact-Assessment-for-Fethiye-Advanced-Biological-Waste-Water-Treatment-Plant-Second-Stage-Units-Application-Project.txt

|

| 175 | Wadi Arab Project Completion Report, Volumes 1,2,3 and 4, submitted in June 2001 for both Projects to Water Authority of Jordan (WAJ); https://tecogrp.com/wadi-arab-waste-water-treatment-plant/

|

| 176 | Project Financed by Kreditanstalt fur Wiederaufbau (KfW), in the framework of the German Jordanian Cooperation |

| 177 | Susan Wolf and Neil Stanley, Wolf and Stanley on Environmental Law, sixth edition 2016, published by Routledge, 2.8 - A specialist environmental court? 60 |

| 178 | The Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017, UK Statutory Instruments 2017 No. 571 |

| 179 | The Town and Country Planning and Infrastructure Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Amendment) Regulations 2018, Statutory Instruments, No. 695 |

| 180 | The EIA Regulations: Two Years On, 16 May 2019, https://npaconsult.co.uk/article-type/environmental-design/>, |

| 181 | The Environmental Impact Assessment (Amendment) (Northern Ireland) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 (revoked), UK Statutory Instruments 2019 No 123 |

| 182 | Ref: Full Anthropogenic Environmental Impact Analysis (EIA) process Chart for a Project, 36. |

| 183 | Brian Barr and Leo Grutters, Institution of Civil Engineers, FIDIC User’s Guide, Third Edition, Thomas Telford Ltd, Ch. 1, 1.1 Construction contracts, line2 3 |

| 184 | Stuart Bell et al, Environmental, lines 8-12 7 |

| 185 | Stuart Bell et al, Box 1.1, Definitions of the environment, 8 |

| 186 | Ref: Richard Card and Jill Molloy, (Card, Cross & Jones), Criminal Law: (22nd edition, OUP 2016), Codification, 1.70 lines 1-7, 30; Stuart Bell et al, Environmental Principles, para 1, 55; Lynton K. Caldwell (1988) Environmental Impact Analysis (EIA): Origins, Evolution, and Future Directions, Impact Assessment, 6:3-4, 75-83, DOI: 10.1080/07349165.1988.9725648, concluding sentence, p 83. |

| 187 | EA 2021, Part 1, c 1, s 16 environmental monitoring (1)(a)(b)(c)(2)(3)(4)(5); Antarctic Protocol, Annex 1, Environmental Impact Assessment, article 5, monitoring (1)(2)(a)(b) |

| 188 | John Glasson and Riki Therivel, Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment, 5th Edition, 3.8 Infrastructure Planning (EIA) Regulations 2017, column2, para 1 76 |

| 189 | EIAR 2017, Schedule 1 |

| 190 | Directive 2011/92/EU of European Parliament and the Council, 13 December 2011, on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment (codification) Article 4(1)(2) Annex 1, Annex 2 |

| 191 | Stephen Tromans QC, Environmental Impact Assessment, 2nd Edition, 2.7, lines 1-4 17 |

| 192 | Brian Barr and Leo Grutters, FIDIC Users’ Guide, Third Edition, ICE publishing through Thomas Telford 2014, 1.3 The Traditional FIDIC Conditions of Contract 5 |

| 193 | ‘The International Federation of Consulting Engineers’ (FIDIC) https://fidic.org> |

| 194 | FIDIC, International Federation of Consulting Engineers, The Global Voice of Consulting Engineers.; https://fidic.org/world-bank-signs-five-year-agreement-use-fidic-standard-contracts

|

| 195 | Ref: Chapter 5, “Framework for ‘EIA’ towards substantial Completion”. |

| 196 | FIDIC EPC/Turnkey Projects, 1st Edition 1999, ISBN 2-88432-021-0, 8 Commencement of Works, 8.1 Commencement of Works |

| 197 | Ibid, 8.3, programme |

| 198 | Ibid, 3 The Employer’s Administration, 3.1 The Employer’s Representative (International Consultant) |

| 199 | Ibid, 4, The Contractor |

| 200 | Example: Ref: The Institution of Civil Engineers, Proceedings, Part 1, Design and Construction, December 1989, Volume 86, The co-ordinate programme (for the ‘Salford Quays Project) for Salford Docks Urban Renewal 1082 |

| 201 | FIDIC Conditions of Contract for Plant and Design-Build, 1st Edition 1999, ISBN 2-88432-023-07, 3 The Engineer, 3.1 Engineer’s Duties and Authority |

| 202 | Climate Change Act 2008, UK Public General Acts 2008 c 27 |

| 203 | Environment Act 2021, UK Public General Act 2021 c 30 |

| 204 | PAS 2080:2016 - Carbon Management in Infrastructure, Construction Leadership Council, The Green Construction Board, published by British Standards Institution, ISBN 978 0 580 90155 3, 4th May 2016 |

| 205 | Climate Change Act 2008, UK Public General Acts 2008 c 27, Part 1 Carbon Targeting and budgeting, s1 - s31 |

| 206 | Ibid, s4, s10 |

| 207 | Ibid, s11 |

| 208 | Ibid, s13, s15 |

| 209 | Ibid, s24, s25 |

| 210 | Environment Act 2021, UK Public General Act 2021 c 30, Chapter 1 Improving the natural environment, Environmental targets, s1 - s7. |

| 211 | Ibid, s8, s15 |

| 212 | Ibid, s16 |

| 213 | Ibid, s17, s19 |

| 214 | Ibid, s20, s21 |

| 215 | Ibid, PART 3, S50, S51 |

| 216 | ibid, s52, s56 |

| 217 | Ibid, s57, s63 |

| 218 | Ibid, s64, s71 |

| 219 | Ibid, PART 4, s72, s73 |

| 220 | Ibid, s74, s77 |

| 221 | Ibid PART 5, S78, s79 |

| 222 | Ibid, s80, s84 |

| 223 | Ibid, s95, s87 |

| 224 | Ibid, s88, |

| 225 | Ibid, s89, s93 |

| 226 | Ibid, s94, s97 |

| 227 | Ibid, PART 6, s98, s101 |

| 228 | Ibid, s142, s149 |

| 229 | Environmental Act 2021, UK Public General Acts, 2021 c 30 |

| 230 | EA 2021, PART 1, Environmental Governance, Chapter 1, Improving the natural environment, s 1. |

| 231 | Ibid, s 8 |

| 232 | ibid, s 16 |

| 233 | ibid, s 17 |

| 234 | ibid, s20, s21. |

| 235 | ibid, PART 3 |

| 236 | ibid, PART 4, s72, 73 |

| 237 | ibid, s74, 75,76,77 |

| 238 | ibid, PART 5, 78, 79 |

| 239 | ibid, s80, 81, 82 83 84 |

| 240 | ibid,85, 86 87 |

| 241 | ibid, 88 |

| 242 | ibid, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93 |

| 243 | ibid, 94, 95, 96, 97 |

| 244 | ibid, PART 8, s140 |

| 245 | EIAR 2017, General, s4. Environmental impact process. |

| 246 | Climate Change Act 2008, UK Public General Acts, 2008, c. 27 |

| 247 | ibid, Part 1 Carbon target and budgeting, The target for 2050, 1, 2, 3, Carbon budgeting, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10, limit on use of carbon units, 11, indicative annual ranges, 12, Proposals and policies for meeting carbon budgets, 13,14,15, Determination whether objectives met, 16,17,18,19,20, Alteration of budgets or budgetary periods, 21,22,23, Targeting greenhouse gases, 24,25, Carbon units, carbon accounting and the net UK carbon account, 26,27,28, Other supplementary provisions, 29,30,31. |

| 248 | ibid, Part 2, The Committee,32, Functions of the Committee,33,34,35,36,37,38, Supplementary provisions,39,40,41,42, Interpretation,43. |

| 249 | ibid, Part 3, Trading Schemes,44,45,46, Authorities and regulations,47,48,49, Other supplementary provisions, 50,51,52,53,54, Interpretation,55 |

| 250 | ibid Part 4, National reports and programmes,56,57,58,59,60, Reporting authorities: non-devolved functions,61,62,63,64,65, Interpretation 70. |

| 251 | ibid Part 5, Other provisions, Waste reduction schemes, 71,72,73,74,75, Collection of household waste,76 Charges for carrier bags,77, Renewable transport fuel obligations,78, Carbon emissions reduction targets,79, Miscellaneous,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,8, Part 6, General supplementary provisons,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101. |

| 252 | EA 2021, s20 |

| 253 | ibid, s40 |

| 254 | Carbon Management in Infrastructure, PAS 2080: 2016, Construction Leadership Council, The Green Construction Board, British Standard Institute, (bsi), 9 Reporting 9.1, 9.2, 9.3, 9.4, 9.5. |

| 255 | Ibid, Part 1, Other supplementary provisions, 29, 30 |

| 256 | Carbon Management in Infrastructure, PAS 2080: 2016, Construction Leadership Council, The Green Construction Board, British Standard Institute, (bsi) |

| 257 | Climate Change Act 2008, UK Public General Acts, 2008, c 27, Part 1, Carbon budgeting 4,5,6,7,8,9,10. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).