Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

04 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Participants

2.2. Measures

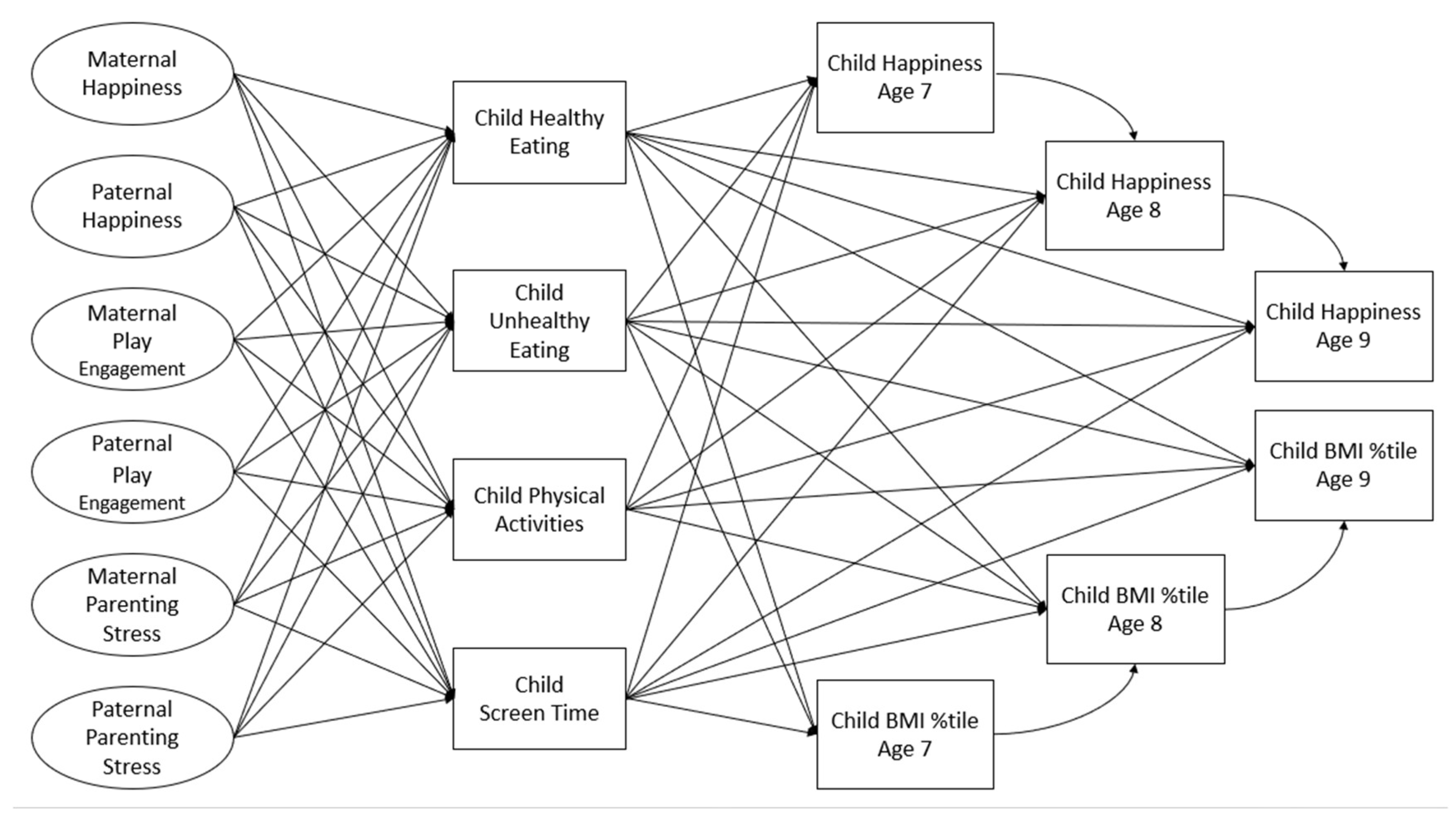

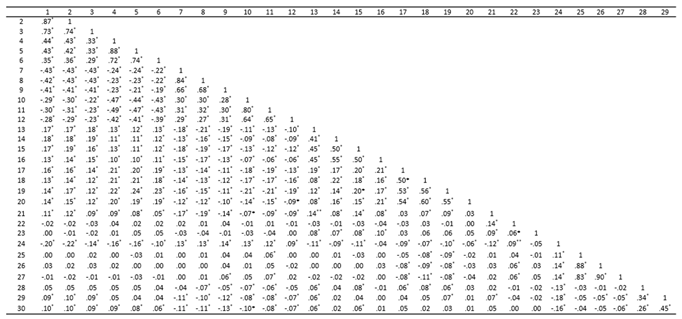

2.3. Statistical Analysis

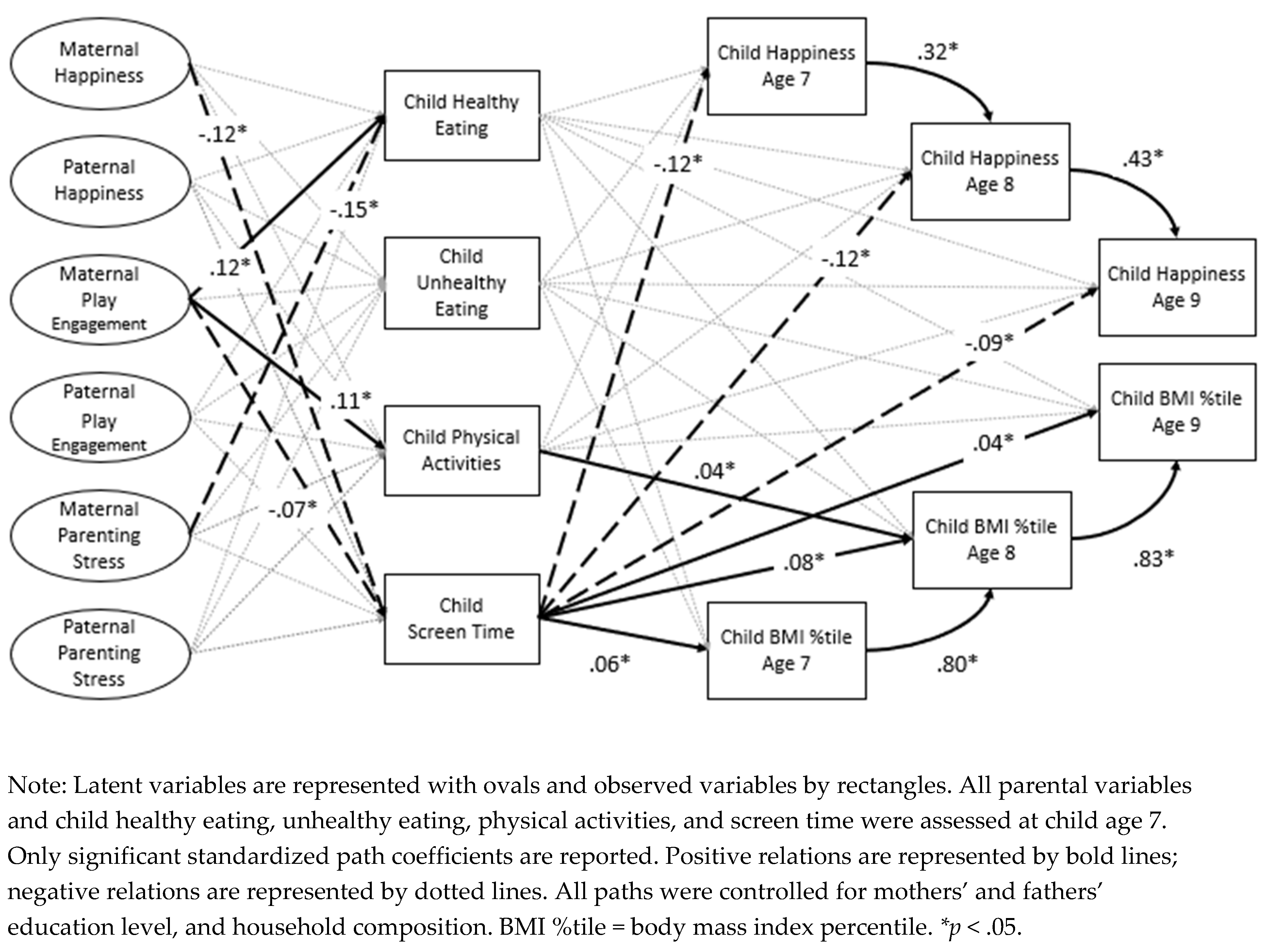

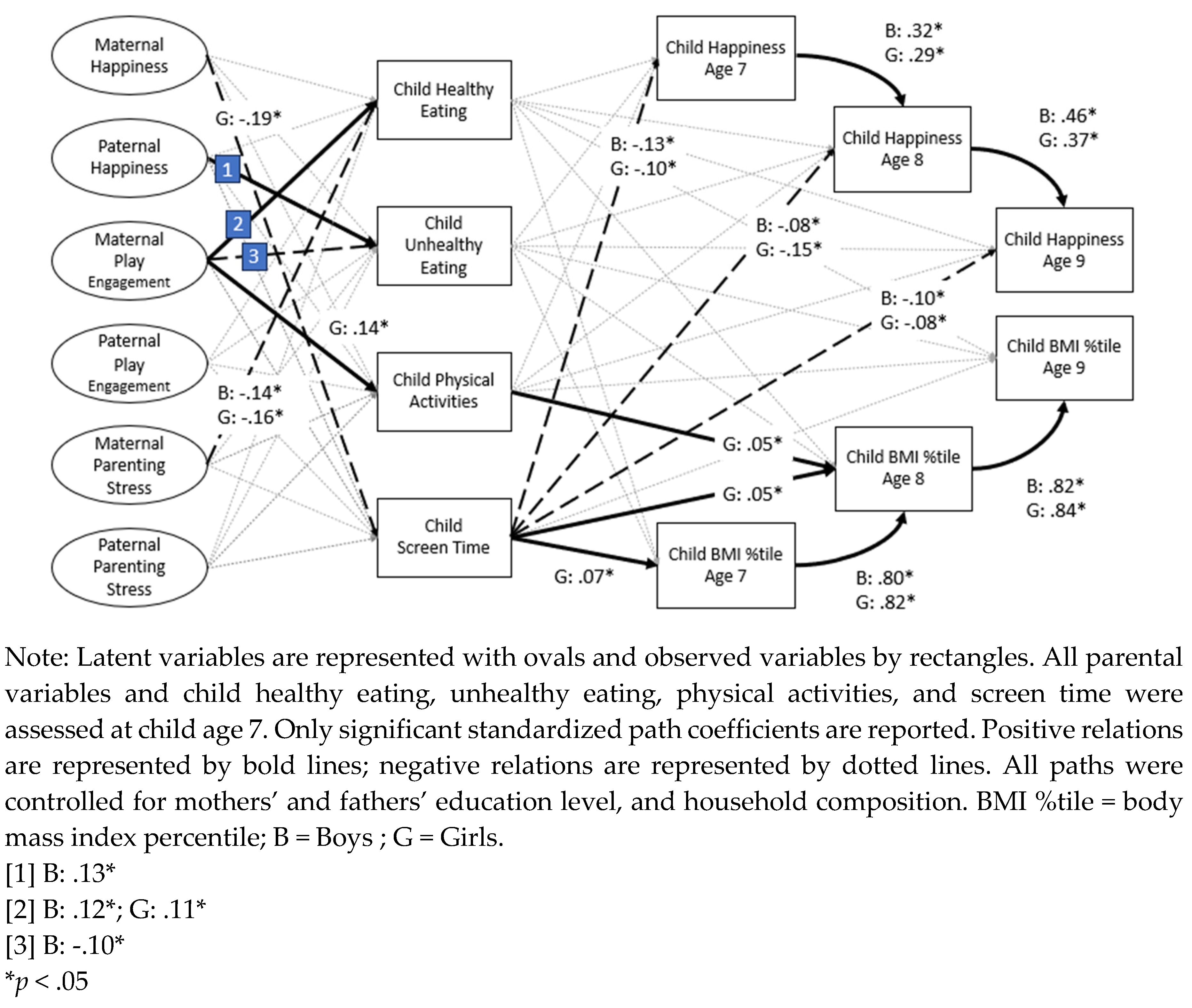

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durocher, E.; Gauvin, L. Adolescents’ Weight Management Goals: Healthy and Unhealthy Associations with Eating Habits and Physical Activity. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Griffiths, P.; Sherar, L.B.; McGeorge, S.; Haycraft, E. Reducing Screen-Time and Unhealthy Snacking in 9–11 Year Old Children: The Kids FIRST Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, M.; Llewellyn, A.; Owen, C.G.; Woolacott, N. Predicting Adult Obesity from Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Obesity and Overweight Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Park, S. Childn and Adolescents Obesity - the Last Window to Prevent Side Effects Available online: http://www.monews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=321207.

- Kang, Y. Exploring the Constructs of Happiness of Elementary Students. J. Elem. Educ 2008, 21, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hoare, E.; Milton, K.; Foster, C.; Allender, S. The Associations between Sedentary Behaviour and Mental Health among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, T.S.; Brookie, K.L.; Carr, A.C.; Mainvil, L.A.; Vissers, M.C.M. Let Them Eat Fruit! The Effect of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption on Psychological Well-Being in Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171206. [CrossRef]

- Hood, R.; Zabatiero, J.; Zubrick, S.R.; Silva, D.; Straker, L. The Association of Mobile Touch Screen Device Use with Parent-Child Attachment: A Systematic Review. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 1606–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. South Korean Children among World’s Unhappiest Available online: https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/893875.html.

- Birch, L.L.; Ventura, A.K. Preventing Childhood Obesity: What Works? Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, S74–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W.; Wallander, J.L.; Felt, J.M.; Elliott, M.N.; Schuster, M.A. Associations of Parental General Monitoring with Adolescent Weight-Related Behaviors and Weight Status. Obesity 2019, 27, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadsden, V.L., Ford, M. Breiner, H. Parenting Matters : Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8; The National Academies Press: Washington DC, 2016.

- Balantekin, K.N.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Francis, L.A.; Ventura, A.K.; Fisher, J.O.; Johnson, S.L. Positive Parenting Approaches and Their Association with Child Eating and Weight: A Narrative Review from Infancy to Adolescence. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuis, L.; van Grieken, A.; Renders, C.M.; HiraSing, R.A.; Raat, H. Parenting Style, the Home Environment, and Screen Time of 5-Year-Old Children; The ‘Be Active, Eat Right’ Study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, N.; Sioen, I.; Braet, C.; Eiben, G.; Hebestreit, A.; Huybrechts, I.; Vanaelst, B.; Vyncke, K.; De Henauw, S. Stress, Emotional Eating Behaviour and Dietary Patterns in Children. Appetite 2012, 59, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, E., Choi, H. Relationships among Psychological Characteristics of Infant-Father, Parenting Engagement and Attitude, and Young Children’s Interactive Peer Play. J Early Child. Educ Educ. Welf. 2014, 18, 229–251.

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Sheldon, K.M.; Schkade, D. Pursuing Happiness: The Architecture of Sustainable Change. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.L.; Cox, M.J. Pleasure in Parenting and Father-Child Attachment Security. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2020, 22, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, N.R.R.; Maia, E.C.; Varga, I.V.D. Os Benefícios Do Brincar Para a Saúde Das Crianças: Uma Revisão Sistemática. Arq. Ciências da Saúde 2018, 25, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

- Marjanovič-Umek, L.; Fekonja-Peklaj, U.; Podlesek, A. The Effect of Parental Involvement and Encouragement on Preschool Children’s Symbolic Play. Early Child Dev. Care 2014, 184, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S. How Child’s Play Impacts Executive Function–Related Behaviors. Appl. Neuropsychol. Child 2014, 3, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, F.P. Children, Play, and Development; Sage Publications; 1991.

- Abidin, R.R. Parenting Stress Index, Third Edition; 2014.

- Anthony, L.G.; Anthony, B.J.; Glanville, D.N.; Naiman, D.Q.; Waanders, C.; Shaffer, S. The Relationships between Parenting Stress, Parenting Behaviour and Preschoolers’ Social Competence and Behaviour Problems in the Classroom. Infant Child Dev. 2005, 14, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J.; Schechter, J.C.; Neely, B.; Reyes, C.; Maguire, R.L.; Perrin, E.M.; Ksinan, A.J.; Kollins, S.H.; Fuemmeler, B.F. Parenting Stress, Child Weight-Related Behaviors, and Child Weight Status. Child. Obes. 2022, 18, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Owen, B.; Lauver, D.R. Different Types of Parental Stress and Childhood Obesity: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1740–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N.J.; Volling, B.L.; Barr, R. Fathers Are Parents, Too! Widening the Lens on Parenting for Children’s Development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2018, 12, 152–157. [CrossRef]

- Khandpur, N.; Blaine, R.E.; Fisher, J.O.; Davison, K.K. Fathers’ Child Feeding Practices: A Review of the Evidence. Appetite 2014, 78, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding-Singh, P. Dining with Dad: Fathers’ Influences on Family Food Practices. Appetite 2017, 117, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musick, K.; Meier, A.; Flood, S. How Parents Fare. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2016, 81, 1069–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raley, S.; Bianchi, S.M.; Wang, W. When Do Fathers Care? Mothers’ Economic Contribution and Fathers’ Involvement in Child Care. Am. J. Sociol. 2012, 117, 1422–1459. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S.M. Family Change and Time Allocation in American Families. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2011, 638, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., Choi, J., Kim, H. Father’s Awareness and State on Parental Involvement and Paternal Difficulties. Korean Soc. Early Child. Educ. 2017, 811–829.

- McDonnell, C.; Luke, N.; Short, S.E. Happy Moms, Happier Dads: Gendered Caregiving and Parents’ Affect. J. Fam. Issues 2019, 40, 2553–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pychyl, T.A.; Coplan, R.J.; Reid, P.A.. Parenting and Procrastination: Gender Differences in the Relations between Procrastination, Parenting Style and Self-Worth in Early Adolescence. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2002, 33, 271–285. [CrossRef]

- Morawska, A. The Effects of Gendered Parenting on Child Development Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurino, E. Do Boys Eat Better than Girls in India? Longitudinal Evidence on Dietary Diversity and Food Consumption Disparities among Children and Adolescents. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2017, 25, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampinen, E.-K.; Eloranta, A.-M.; Haapala, E.A.; Lindi, V.; Väistö, J.; Lintu, N.; Karjalainen, P.; Kukkonen-Harjula, K.; Laaksonen, D.; Lakka, T.A. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Socioeconomic Status among Finnish Girls and Boys Aged 6–8 Years. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kye, S.Y.; Kwon, J.H.; Park, K. Happiness and Health Behaviors in South Korean Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Epidemiol. Health 2016, 38, e2016022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromwich, J. Study of Teenagers Asks: Who’s Happier, Boys or Girls? 2016.

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency Changes in Adolescent Health Behavior before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Press Re-Lease; 2022.

- Panel Study on Korean Panel Study on Korean Children. 2018.

- Bahk, J.; Yun, S.-C.; Kim, Y.; Khang, Y.-H. Impact of Unintended Pregnancy on Maternal Mental Health: A Causal Analysis Using Follow up Data of the Panel Study on Korean Children (PSKC). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyumbomirsky, S., Lepper, H.S. A Measure of Subjective Happiness: Preliminary Reliability and Construct Validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K., Kang, H. Research: Development of the Parenting Stress Scale. J. Korean Home Econ. Assoc. 1997, 35, 141–150.

- Yang, H.-M. Associations of Socioeconomic Status, Parenting Style, and Grit with Health Behaviors in Children Using Data from the Panel Study on Korean Children (PSKC). Child Heal. Nurs. Res. 2021, 27, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Choi, E. The Reciprocal Longitudinal Relationship between Executive Dysfunction and Happiness in Korean Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Child Development Chart Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/contents.es?mid=a20303030400.

- Allison, P.D. Missing Data Techniques for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M. W. , Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. In Testing structural equation models; Newbury Park, 1993; pp. 136–162.

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, E.; Ray, C.; Määttä, S.; Figueiredo, R.A.O.; Leppänen, M.H.; Pajulahti, R.; Koivusilta, L.; Korkalo, L.; Nissinen, K.; Vepsäläinen, H.; et al. Parental Happiness Associates With the Co-Occurrence of Preschool-Aged Children’s Healthy Energy Balance-Related Behaviors. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 1493–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M.; Reeve, J. The Influence of Positive Affect on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: Facilitating Enjoyment of Play, Responsible Work Behavior, and Self-Control. Motiv. Emot. 2005, 29, 295–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.Y.; Doh, H.-S. Actor-Partner Effects of Marital Satisfaction, Happiness and Depression on Parenting Behaviors of Parents with Young Children. Korean J. Child Stud. 2020, 41, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, K.R. The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds. Pediatrics 2007, 119, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, A.; Dittman, C.K.; Rusby, J.C. Promoting Self-Regulation in Young Children: The Role of Parenting Interventions. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 22, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montroy, J.J.; Bowles, R.P.; Skibbe, L.E.; Foster, T.D. Social Skills and Problem Behaviors as Mediators of the Relationship between Behavioral Self-Regulation and Academic Achievement. Early Child. Res. Q. 2014, 29, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D. Authoritative Parenting Revisited: History and Current Status. In Authoritative parenting : synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development; American Psychological Association: Washington DC, 2013; pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett, D.J.; Burt, N.M.; Edwards, E.S.; Deater-Deckard, K. Intergenerational Transmission of Self-Regulation: A Multidisciplinary Review and Integrative Conceptual Framework. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 602–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sominsky, L.; Spencer, S.J. Eating Behavior and Stress: A Pathway to Obesity. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, N.; Viner, R.M. Effects of Screentime on the Health and Well-Being of Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartanyà-Hueso, À.; Lidón-Moyano, C.; González-Marrón, A.; Martín-Sánchez, J.C.; Amigo, F.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M. Association between Leisure Screen Time and Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Spanish Children. J. Pediatr. 2022, 241, 188–195.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, H.B.; Christakis, N.A. Association of Facebook Use with Compromised Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N.; Campbell, W.K. Decreases in Psychological Well-Being among American Adolescents after 2012 and Links to Screen Time during the Rise of Smartphone Technology. Emotion 2018, 18, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.D.; Lim, A.F.; Felt, J.; Carrier, L.M.; Cheever, N.A.; Lara-Ruiz, J.M.; Mendoza, J.S.; Rokkum, J. Media and Technology Use Predicts Ill-Being among Children, Preteens and Teenagers Independent of the Negative Health Impacts of Exercise and Eating Habits. Comput. Human Behav. 2014, 35, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. More Time on Technology, Less Happiness? Associations Between Digital-Media Use and Psychological Well-Being. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Y.; Bègue, L.; Bushman, B.J. Violent Video Games Stress People Out and Make Them More Aggressive. Aggress. Behav. 2013, 39, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, S.; Grippo, A.J.; London, S.; Goossens, L.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyrka-Allchorne, K.; Cooper, N.R.; Gossmann, A.M.; Barber, K.J.; Simpson, A. Differential Effects of Film on Preschool Children’s Behaviour Dependent on Editing Pace. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Mu, M.; Liu, K.; He, Y. Screen Time and Childhood Overweight/Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Child. Care. Health Dev. 2019, 45, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellissimo, N.; Pencharz, P.B.; Thomas, S.G.; Anderson, G.H. Effect of Television Viewing at Mealtime on Food Intake After a Glucose Preload in Boys. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 61, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B. When Couples Become Parents : The Creation of Gender in the Transition to Parenthood; University of Tonto Press: Toronto, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Man Yee Kan; Sullivan, O. ; Gershuny, J. Gender Convergence in Domestic Work: Discerning the Effects of Interactional and Institutional Barriers from Large-Scale Data. Sociology 2011, 45, 234–251. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Petersen, A.; Fraser, S. Food, Fat and Family: Thinking Fathers through Mothers’ Words. Womens. Stud. Int. Forum 2014, 44, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, J. Gender Differences in Contribution to Domestic Work and Childcare Associated with Outsourcing in Korea. Fam. Environ. Res. 2020, 58, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Equality in Marriage Is Just a Thought... The Burden of Childcare Still Falls on ‘Mom’ Available online: http://www.koreanewstoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=67688.

- Lee, S. Last Year, Parental Leave Increased by 18.6%, Surpassing 130,000 People... ‘Dads Taking Parental Leave’ Saw a Sharp Rise of 30%. 2023.

- Wallander, J.L.; Koot, H.M. Quality of Life in Children: A Critical Examination of Concepts, Approaches, Issues, and Future Directions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable (N = 1551) | |

| Father's age Year (SD) | 40.31 (3.95) |

| Mother's age Year (SD) | 37.91 (3.72) |

| Child's age Month (SD) | 87.91 (1.54) |

| Child's gender (%) | |

| Boy | 51.3 |

| Girl | 48.7 |

| Father respondent’s educational level (%) | |

| 8th grade or less | 0.5 |

| High school graduate and GED | 26.2 |

| Some college, or 2-year degree | 20.2 |

| 4-year college graduate | 42.3 |

| More than a 4-year college degree | 10.8 |

| Mother respondent’s educational level (%) | |

| 8th grade or less | 0.4 |

| High school graduate and GED | 28.8 |

| Some college, or 2-year degree | 27.7 |

| 4-year college graduate | 37.5 |

| More than a 4-year college degree | 5.6 |

| Household composition (%) | |

| Parents and child/ren | 88.4 |

| Grandparents, parents, and child/ren | 7.4 |

| Parents, child/ren, and relative/s | 0.8 |

| Grandparents, parents, child/ren, and relative/s | 3.3 |

| Other | 0.1 |

| Parental Variables | Scale | Total | Mother | Father | |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Happiness | |||||

| In general, I consider myself happy. | 1 - 7 | 5.40 (1.08) | 5. 36 (1.10) | 5.44 (1.07) | |

| Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself happy. | 5.32 (1.11) | 5.27 (1.14) | 5.37 (1.08) | ||

| I enjoy life regardless of what is going on. | 5.03 (1.18) | 5.02 (1.22) | 5.05 (1.13) | ||

| Play Engagement | |||||

| I do arts and crafts with my child. | 1 - 4 | 1.90 (0.71) | 2.05 (0.70) | 1.74 (0.68) | |

| I do puzzles and/or board games with my child. | 1.90 (0.69) | 1.90 (0.70) | 1.90 (0.69) | ||

| I build things and/or play with blocks with my child. | 1.83 (0.68) | 1.91 (0.71) | 1.74 (0.66) | ||

| I talk about nature or do STEM projects with my child. | 1.78 (0.68) | 1.77 (0.71) | 1.78 (0.66) | ||

| Parenting Stress | |||||

| I am not sure if I could be a good parent. | 1 - 5 | 2.30 (0.88) | 2.42 (0.90) | 2.18 (0.84) | |

| I am not sure if I could raise my child properly. | 2.15 (0.85) | 2.26 (0.97) | 2.03 (0.79) | ||

| I feel sometimes that my child is behind his or her peers because I am not doing enough as a parent. | 2.23 (0.94) | 2.33 (0.84) | 2.22 (0.88) | ||

| Child Variables | Child M (SD) |

Boys M (SD) |

Girls M (SD) |

t-test (df = 1526) |

||

| Healthy eating | 4 - 12 | 8. 74 (1.76) |

8.78 (1.84) |

8.69 (1.68) |

t = 1.03, p = .02 |

|

| Unhealthy eating | 3 - 9 | 6.39 (1.56) |

6.48 (1.61) |

6.30 (1.50) |

t = 2.24, p = .01 |

|

| Physical activities (min/week) | 0 - 56 | 27.03 (6.50) |

28.02 (6.00) |

25.98 (6.83) |

t = 2.34, p = .13 |

|

| Screen time (hrs/week) | 0 - 50 | 13.04 (7.07) |

13.45 (7.17) |

12.60 (6.95) |

t = 5.26, p = .08 |

|

| Child happiness at age 7 | 0 - 24 | 19.52 (2.85) | 19.09 (2.91) |

19.99 (2.71) |

t = -6.31, p = .01 |

|

| Child happiness at age 8 | 0 - 24 | 19.98 (2.63) | 19.52 (2.82) |

20.45 (2.32) |

t = -6.84, p = .01 |

|

| Child happiness at age 9 | 0 - 24 | 19.92 (2.71) | 19.60 (2.92) |

20.26 (2.43) |

t = -4.58, p = .01 |

|

| BMI percentile at age 7 | 1 - 100 | 53.43 (31.30) | 53.56 (31.46) |

53.31 (31.15) |

t = 0.17, p = .56 |

|

| BMI percentile at age 8 | 1 - 100 | 58.40 (31.30) |

62.33 (30.87) |

54.31 (31.25) |

t = 4.86, p = .71 |

|

| BMI percentile at age 9 | 1 - 100 | 55.76 (30.52) |

58.90 (30.43) |

52.54 (30.32) |

t = 3.90, p = .23 |

|

|

| [1] Mother’s happiness - In general, I consider myself happy; [2] Mother’s happiness - Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself happy; [3] Mother’s happiness - I enjoy life regardless of what is going on; [4] Father’s happiness - In general, I consider myself happy; [5] Father’s happiness - Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself happy; [6] Father’s happiness - I enjoy life regardless of what is going on; [7] Mother’s parenting stress – I am not sure if I could be a good parent; [8] Mother’s parenting stress – I am not confident that I can raise my child properly; [9] Mother’s parenting stress – I feel my child is behind his/her peers because I do not parent him/her well; [10] Father’s parenting stress – I am not sure if I could be a good parent; [11] Father’s parenting stress – I am not confident that I can raise my child properly; [12] Father’s parenting stress – I feel my child is behind his/her peers because I do not parent him/her well; [13] Mother’s play engagement – I do arts and crafts with my child; [14] Mother’s play engagement – My child and I play board games and do puzzles together; [15] Mother’s play engagement - My child and I talk about nature and do science projects together; [16] Mothe’s play engagement - My child and I build something or play with toys together; [17] Father’s play engagement – I do arts and crafts with my child; [18] Father’s play engagement – My child and I play board games and do puzzles together; [19] Father’s play engagement - My child and I talk about nature and do science projects together; [20] Father’s play engagement - My child and I build something or play with toys together; [21] Child healthy eating; [22] Child unhealthy eating; [23] Child physical activities; [24] Child screen time; [25] Child weight status at age 7; [26] Child weight status at age 8; [27] Child weight status at age 9; [28] Child happiness at age 7; [29] Child happiness at age 8; [30] Child happiness at age 9. *p < .05 |

| Measurement Models | Mother | Father | |||

| Factor Loadings | Model Fit | Factor Loadings | Model Fit | ||

| Parental Happiness | |||||

| In general, I consider myself happy. | 0.93 | RMSEA = 0.00 CFI = 1.00 TLI = 1.00 |

0.93 | RMSEA = 0.00 CFI = 1.00 TLI = 1.00 |

|

| Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself happy. | 0.94 | 0.94 | |||

| I enjoy life regardless of what is going on. | 0.78 | 0.78 | |||

| Play Engagement | |||||

| I do arts and crafts with my child. | 0.69 | RMSEA = 0.06 CFI = 0.99 TLI = 0.98 |

0.69 | RMSEA = 0.05 CFI = 1.00 TLI = 0.99 |

|

| I do puzzles and/or board games with my child. | 0.76 | 0.76 | |||

| I build things and/or play with blocks with my child. | 0.75 | 0.75 | |||

| I talk about nature or do STEM projects with my child. | 0.76 | 0.76 | |||

| Parenting Stress | |||||

| I am not sure if I could be a good parent. | 0.91 | RMSEA = 0.00 CFI = 1.00 TLI = 1.00 |

0.88 | RMSEA = 0.00 CFI = 1.00 TLI = 1.00 |

|

| I am not sure if I could raise my child properly. | 0.93 | 0.91 | |||

| I feel sometimes that my child is behind his or her peers because I am not doing enough as a parent. | 0.74 | 0.73 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).