1. Introduction

Nowadays, teacher identity is an evolving and changing concept [

1]. This is especially evident for teachers in training due to the countless influences around, of course epistemological, but also ones that are personal, inter-personal or contextual in nature. These shape the heritage framework of teacher identity. All these aspects are interdependent and affect the idea teachers have of themselves and the profession [

2]. Thus, this identity becomes "an evolving concept under constant reformulation through life experiences and relationships" [

3] (p. 495). New approaches are needed in an era in which digital and technological advances affect all processes generated between heritage and identity links. For this reason, processes based on arts can be useful for research on heritage and even heritage education. These methodologies understand heritage education from an active and creative point of view, being tools to develop identity values, intercultural respect and social change [

4].

On this account, Body-camera emerges as a tool to create heritage and identity. It acts as a memory machine that goes beyond the physical body demanding to bring back the past towards present situations [

5]. Inevitably, the private sphere, personal and individual dilemmas, joins the public sphere. This externalization of memories and life goals allows the process of identity creation to be reviewed, including the one that concerns us. Teachers’ identities are "composed and improvised as [they] live [their] lives embodying knowledge and engaging contexts" [

6] (p.4).

The use of interactive video essay in the training processes of future teachers enriches the professional configuration by providing tangible and immediate examples where participants are placed in an empathetic position, resonating with their life experiences and allowing them to "creatively appropriate" heritage [

7]. This interaction can take a formalist approach using devices whose format allows for physical interaction, but also a conceptual and symbolic one, providing these future teachers with an active role within their training process [

8]. These processes occur thanks to the ability of this medium to raise awareness and capture sensations of the world from a contemporary point of view, a perspective embedded in a society saturated with audiovisual stimuli [

9].

The combination “Body-camera” was developed assuming three roles: one of mediation as researchers, another as a learning facilitator for teachers in training, and a last one as a guide for participants throughout the creative process, focusing on self-exploration and self-expression. Hence, authorship of the artistic results originating from this creative process belongs entirely to the participants themselves. Video essay was the tool chosen, due to its melding of cinema and documentary [

10]. This hybrid nature is able to create new discourses and opinions from two sources: the subjective point of view of participants and the concept of the body understood as a recording device sensitive to daily stimuli, which are also part of the narrative [

11]. This provides the participants with enough flexibility to develop its creative autonomy and assume an active role, promoting new and transformative social spaces in audiovisual and digital cultures [

12]. The adoption of this methodological approach based on artistic processes contributes to the development of "cognitive, instrumental and socio-emotional competences required to build both, personal and professional identities" [

13] (p. 616).

The main aim of this research is to reveal the notions about the teaching identity of educators at a key moment in their training. Aunever constructing teaching identity the moment in which direct contact with professional reality occurs in real school contexts is decisive. Thus, the device is created as a space for reflection through creation different from traditional models of audiovisual creation. To achieve this, group dynamics were constantly used to improve joint efforts among participants. In this sense, the "blind” video editing of the last stage is particularly relevant. This video editing was designed following the premises of three contemporary works: "Life in a day", by Kevin Macdonald; "Spain in a day", by Isabel Coixet; and "Life in a day 2020" by Macdonald, a revision of his previous project in collaboration with the online platform Youtube. The narrative and structure of these audiovisual projects is based on identity aspects, which is why they are direct antecedents for our proposal. Furthermore, they imply the creation of an identity heritage based on personal and shared ties that arise from the artistic proposal. This is especially interesting for the purpose of this research.

All these full-length films gather several recordings recorded by volunteers reflecting a common feeling from different perspectives, and their narrative continuity is subject to the assembly of all the received video clips. Regarding "Life in a day", participants were given some pre-stablished questions about love, dreams and beliefs to make results uniform to a certain extent, thereby creating a precise cultural portrait about Spanish identity. Following the same approach, the subsequent project proposes three questions for participants to think about how their teacher identity affects their memories and life experiences. The answers to these questions, possibly unnoticed until then, bring to the surface some heritage elements linked to them.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology used is based on the arts (Arts-Based Educational Research -ABER-) with an a/r/tographic and ethnographic approach, where artistic practice and theoretical contents are worked horizontally [

14]. Teachers' personal experience served as a source of self-knowledge and its analysis was used as a significant part of this research [

15]. The methodological approach known as A/r/tography [

16] is one of the most influential approaches within Arts-Based Research and propose, a relational inquiry in which the figures of the researcher, the teacher, and the artist blend and overlap. A/r/tography "connects with the concepts of 'embodied thought' and 'situated activity' or 'situated cognition', both of which declare that thought is inseparable both from action and from social and cultural contexts" [

17] (p. 887), turning this methodological proposal into a living investigation [

18]. Video essay was chosen among all the possibilities of Arts-Based Research strategies because of its interesting characteristics: this a/r/tographic structure works at the same time as tool to carries out the theory, and as the means to establish a double narrative link with each individual participant and the group. Thus, on the one hand, each participant contributes to providing new issues and solutions thanks to the interactive nature of the process where they assume a main role. On the other hand, the emotional and collective narrative connection is developed. This connection arises from the different memories that make up each individual teaching identity.

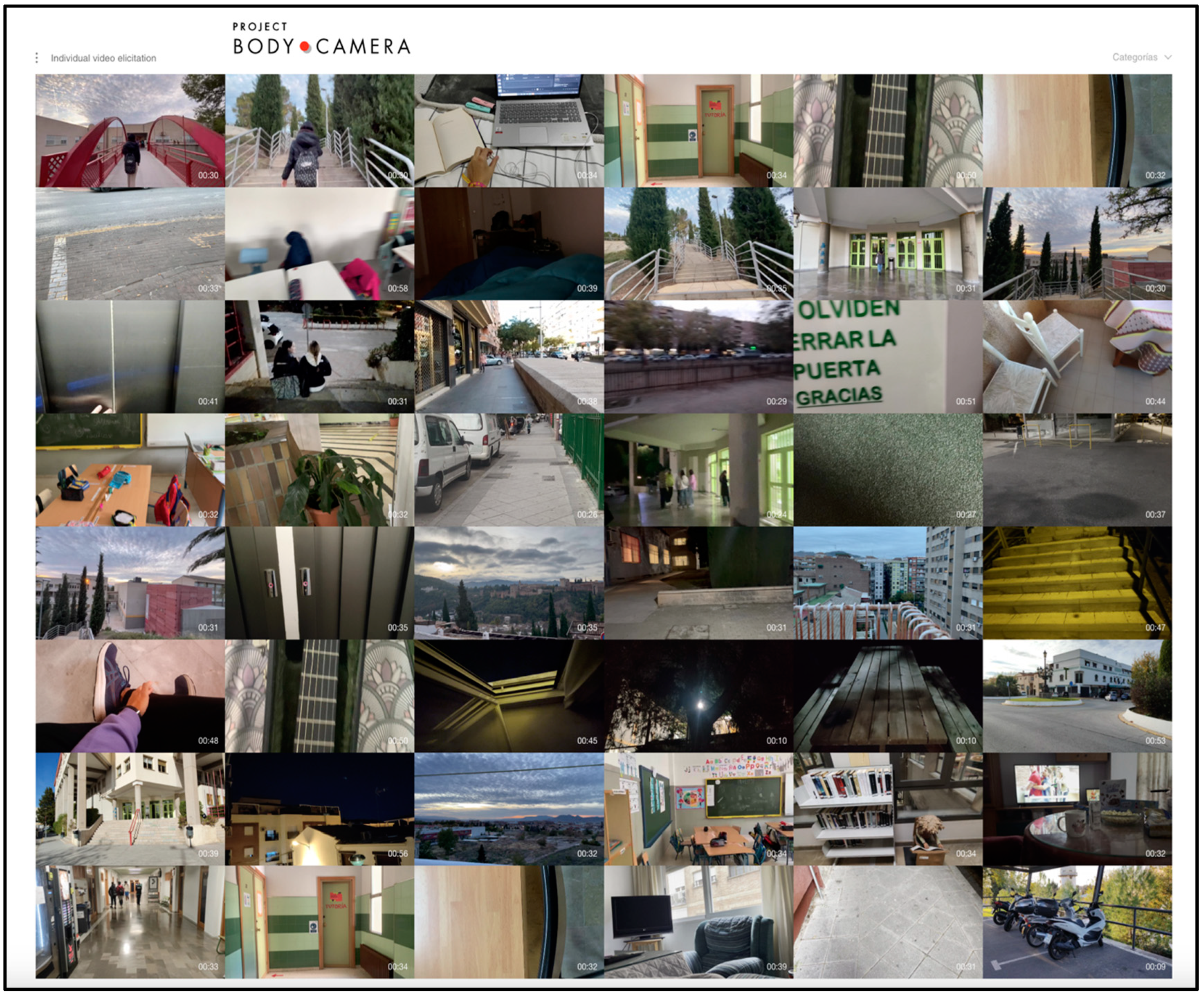

Video elicitation was the analysis tool used in the first stage. This approach allowed recorded stories to be considered testimonies by themselves, capable of introducing new data to the study [

19]. Unlike a simple recording, recorded stories showed the relationship between body and space, which leaves an intermediate gap where memories are placed as a way of embodying memory itself.

After this first stage, defragmentation was used to implement a "deconstructive break" [

20] of the original video elicitation. This process dissolves the narrative in a certain way when "cuts" occur, and leads to the production of a new video editing no longer personal, but shared, resulting in a collective video essay that brings together the experiences of the different participants. This decision not only enhanced the speed and immediacy when viewing the audiovisual content, but it also helped to decontextualize a closed discourse of almost a minute in length. As a result, the obtained video clip happens to be interesting enough to adapt itself more organically within the collective discourse, leading to its own re-signification.

For the subsequent analysis of the results, descriptive sequences were used, each of them consisting of between 25 and 30 frames from every single video essay. This allowed us to appreciate the narrative continuity, including the visual one, showed by the results. Unlike a set of frames extracted from the video essay without an established criterion, this tool creates the need to systematize their selection. Therefore, it proves much more precise to visually describe the action in any audiovisual piece since it encompass the whole video, giving a clear idea of the content without the need of reproducing it.

This research was carried out with last year students of the Primary Education degree, supporting their teaching internships in different schools within the scope of approaching teacher identity from a professional point of view, since they are experiencing an essential stage in the creation of their teacher identity while they change the rol of student for the role of a teacher [

21].

Process Methodology

Three different stages were proposed during two sessions of fieldwork with the participant group to facilitate a better and natural approach to the audiovisual language.

In the first stage, video elicitation was used individually as a tool to answer three questions:

Which memory defines myself the best?

Which space does my body inhabits?

What memory do I have from school that best defines me as a teacher?

Participants had to answer them based on three main premises:

Each video clip had to consist on a single subjective shot of 30 to 60 seconds that could not be cut anywhere.

Oral responses had to be spontaneous, not artificial or rehearsed, in order to have a natural result.

All recorded images had to belong to their daily contexts and should be planned to answer the proposed question, contrary to oral responses. Moreover, having in mind a certain degree of control over the environment was necessary in order to achieve a good audio quality, since videos could not be edited afterwards.

Restrictions on editing respond to the need for simplification of the process, as audiovisual language was not familiar to all of participants. Consequently, they could focus their efforts on delving into their memories and the relationship between their body and the chosen setting.

Subjective shots were mandatory, meaning that recording devices should always be at eye level. The purpose of this choice was to place viewers at the same level as the person recording to grant a better understanding of the author’s point of view.

Horizontal video format, 16:9;

File extension .mov/.mp4;

Minimum resolution 1920x1080, 30 fps

In the second stage, participants were place in pairs. Each one of them took a 10-second video excerpt from the video elicitation of their partner based exclusively on two things: 1. plastic and sound quality, and 2. the feelings that it could evoke. It was important that every excerpt worked on its own, making it necessary to meet some technical aspects (for example, discourse should not be interrupted abruptly) as well as the narrative and poetic ones (the video elicitation content). To achieve all this, participants used the tool CapCut, a video and sound edition software, carefully selected for several reasons, mainly: it has a friendly interface; it is available for different systems and online, and free of charge.

Once all previous material was organized, participants were divided into groups of four for the third stage. Each group had to make a comprehensible video essay without any visual or verbal explanation using the excerpts of the second stage. This last stage was planned as a "blind exercise" since materials were unknown to the groups until the last moment since video elicitations were not previously shared among them to avoid any bias in the previous stage. Upon completion, all four video essays were put together using CapCut again.

Afterwards, descriptive sequences were created following both, the four collective video essays from the second stage, and the one created at the end by combining them. In order to make them, the duration of each video (in seconds) was divided into 30 parts, equal in length, to calculate the time lapse between frames. This quantity was conditional on the duration of the videos (nearly two minutes each) and yet, they could seem too many for such a short work beforehand. However, this is exactly which makes this tool as precise as it is: the possibility to see broadly what happens, how many shots are repeated or which ones are longer than the rest.

3. Results

During this project, 48 video elicitations were obtained. These recordings were used to create four final independent video essays, each of them composed of 12 video excerpts from the video elicitations. All four video essays were put together to create a single, longer one.

The first video essay (

Figure 1) fit together some of the oral stories with family memories, along with a self-evaluation. It evokes a general feeling of taking as little space as possible in society, and contains a brief reference to friendship bonds.

Visually, warm colours are mostly used, being different values of brown the dominant ones. Most of the clips were recorded while walking or inhabiting the outdoor areas of the university campus. This means that spatial and corporal relationships were deliberated, showing several images of transit areas, such as corridors and stairs. Symmetrical shots are frequent, as well as soft lights, avoiding high contrasts.

The second video essay (

Figure 2) delves into personal limits, comfort zones and relationships with the past. There are powerful visual answer, such as the simile between perfectionism and stairs, or the choice to record those spots that enhance intimacy. There are no visual trace of educational centres but they are somehow present in the rest of experiences narrated as people who reflect upon their past to move forwards.

Although there is little variety in the shots used, the stillness seen in all of them arouse the feeling of a private conversation with someone you can hear but not fully see. There is great contrast among the different lights used: some scenes were recorded at night and some others with bright lights, mostly from artificial sources. The continuity of the video essay is negatively affected by this lack of uniformity, reinforced by a common discourse among authors.

The third video essay (

Figure 3) tends to show empty educational spaces. In this sense, there are two clear trends in the choice of spaces: indoors and outdoors areas, constantly interacting.

Cohesion is so well achieved in this video essay that one could assume it is always the same person narrating their experience, as there are some accordance among life goals and project of different participants. The question about the space that their body inhabits is answered in a formal way and refers mostly to the spaces that they transit in a daily basis. From a visual point of view, warm tonalities are again the trend, being brown the main colour of the video.

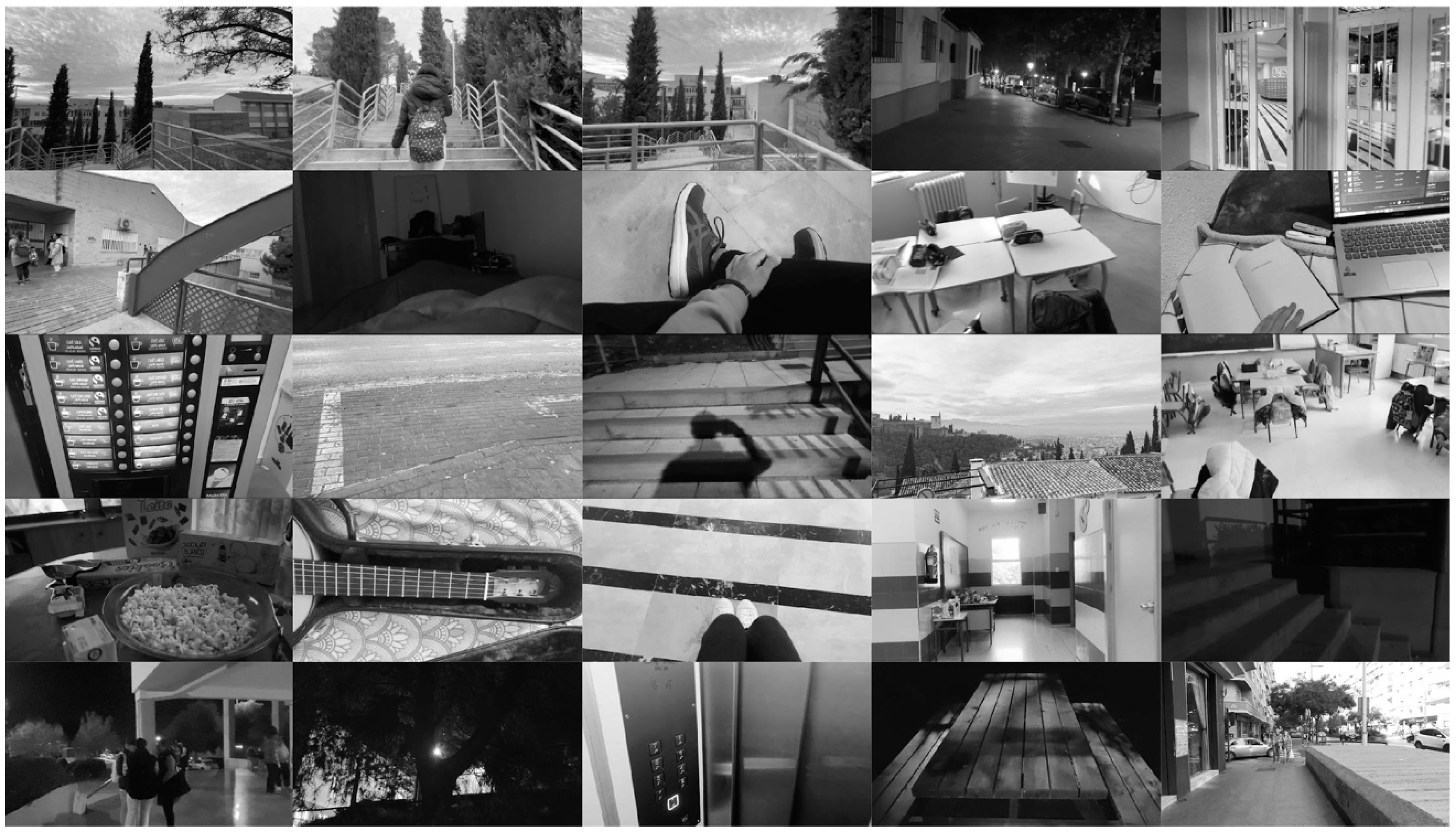

Figure 1.

Descriptive-sequence of the first video essay from 30 frames of the final video.

Figure 1.

Descriptive-sequence of the first video essay from 30 frames of the final video.

Figure 2.

Descriptive-sequence of the second video essay from 30 frames of the final video.

Figure 2.

Descriptive-sequence of the second video essay from 30 frames of the final video.

Figure 3.

Descriptive-sequence of the third video essay from 30 frames of the final video.

Figure 3.

Descriptive-sequence of the third video essay from 30 frames of the final video.

The fourth video essay (

Figure 4) differs completely from the rest in terms of brightness. The spaces presented are mostly dark, either due to the time of the day or the space itself. Urban settings are emphasized, from parking lots to pavements or roads. However, the narrative shared is about nature and the sense of peace and comfort it evokes. The power of friendship to define one's personality is underlined, as well as the need to spend some time alone in everyday life.

The color palette shows little variation, with a tendency to brown. Movement is present in most shots, either of the body or the space, scanning the surroundings with the camera as someone would look around their environment.

Figure 5.

Descriptive-sequence of the collective video essay from 24 frames of the final video.

Figure 5.

Descriptive-sequence of the collective video essay from 24 frames of the final video.

The final video essay, created after putting together the previous clips (

Figure 6), reveals a final result of exceptional narrative and aesthetic quality. Even if colorimetry made it difficult to be immersed at all times, the final video essay was converted to black and white to solve this problem and improve cohesion between all the excerpts. It is worth mentioning that the order in which the four video essays were put together correspond to each team number. Therefore, it was not planned to give a sense of continuity to the narrative, although they work well together.

4. Discussion

The original question of this research looked for an immediate approach of drawing attention to the process of building a professional identity for a group of future teachers. How could different perspectives be shared through a collective process? In this sense, the choreographer Olga de Soto pondered about the remains of scenic works once people do not longer remember or talk about it [

22] (p.127). She solved this issue using a device in which expressing memories would reconstruct the idea of the body and the work itself, since "orality implies not only a commitment on behalf of the speaker, but a responsibility towards memory" [

5] (p.137). In this case, the model Body-camera takes advantage of the potentiality embedded in individual reconstructions, not only as teachers, but as a living bodies that feels, and whose life experiences affect professional environments and influence self-concepts relating to it. In this regard, perspective is understood as a double interaction body-individual [

23]. Firstly as a body that belongs to the world. Secondly, as an individual who makes sense of the world, creating a linking bond between both. Memory should be added to this interaction as a key factor [

24].

Several studies conceive video elicitation as a tool to tease a deeper discussion about certain topics opposed to an interview. This is because it uses different stimuli (photographs, videos, pieces of writing or specific settings) that significantly improve the expression of the connection created towards the object of study [

19]. In this case, the object of study is the processes of building teacher identities, which helps future teacher to understand the relationship between who they are and what they do professionally [

25]. Some relevant studies for our research approach the configuration of teaching identity using a reflective methodology [

26]. These usually work with future teachers using different tools. One of them is the "corporal diary" [

27] to explore the relationship between their corporal dimension and its implication in teaching. Another of them could be a combination of artistic and expressive processes used as recordings of "corporal stories" [

28]. This usually tends to reflect upon the body as the means to live experiences embedded in the training curriculum of future art teachers. Another tool would be the [identity self-portrait] carried out through audiovisual means as a learning-teaching strategy for future secondary teachers [

29].

In a project like this one, it was necessary to present an overview as broad as possible about how these identity processes are managed as a group [

30]. To overcome all possible technical issues, excerpts from video elicitations had to be short in order to facilitate creative processes as well as the subsequent remaining or redefine the narrative had to be accelerated. Putting together all clips was vital in the development of the project, since it transformed students into authors, allowing them to play the role of "prosumers" [

31]. During this process they join creative action with a visual and personal analysis to explore their own self-awareness through audiovisual proposals. Body camera proposes a new methodological approach using video elicitation as a didactic tool, being the subsequent "blind video editing" of excerpts a means to create shared heritages and new visual discourses based on life and professional experiences of participants.

5. Conclusions

After analyzing the results obtained after the implementation of the Body-camera device, we conclude that it has met the proposed aims of this study about teacher identity in pre-service training. Different expressions of visual ideas were triggered for each participant, some of them recurring. These ideas were later developed in group, creating a community of future teachers that share interests, motivations, doubts and convictions, leading to a collective identity. The latter can be seen not only in the video elicitation recorded but in the video essays that were then created.

Unlike the models followed in the previously mentioned cinematic references, the audiovisual products resulting from the different phases of our research do not reflect an authorial perspective. Instead, they are collectively constructed by the participants through a collaborative creative process. The central idea is to emphasize the absence of a singular authoritative voice and underscore the collective contribution of the participants in the creation of the audiovisual products.

We found out that teacher identity is closely related to the vital processes and personal heritage of each one of the people conforming this research experience. There is a powerful link between their self-concept as teachers and their acquired values, either from family or friend relationships. It is particularly interesting to note the definition of their self-concept derived from video elicitations based on the different points of view in which they are positioned: as teachers, as creators and as students. These three aspects are also affected by the personal heritage of each participant, meaning that acquired values, relationships and their past in general make and impact in their education and their profession.

However, some difficulties regarding technical issues were found, most of them relating to the quality of the audiovisual material due to its exportation. The software of choice solved some of these problems, but working with cloud services caused the loss of file information due to compression processes in some cases.

Regarding the artistic quality of results and considering both, visual and sound dimensions, we can determine that they fulfill the purpose of developing a collective view over the processes that build professional identity as future teachers through memories. Although, oral quality was prioritized over visual aspects in some cases, devaluing the plastic and symbolic interest of the videos. Nevertheless, this can be solved through an analytical revision of results together with participants, creating a reflection space to develop more visual discourses and narratives, useful in a possible new project.

Additionally, this device could inspire more flexible learning environments with a focus on students if brought to the schools where participants are teaching. However, this would clash with legal and ethical limitations relating to data and image protection of underage children. To overcome these obstacles, the structure of Body-camera should be readapted. A possible solution would be adapting the design to the legislative framework concerning each context.

Finally, we consider that the device for research that we have experienced open a new teaching strategy based on creation from an active perspective. Moreover, it offers the opportunity to create a web support to store new answers from different participants under the same conditions for further research in this line, taking advantage of new technologies to develop a virtual meeting point outside formal education that contributes to the construction of teaching identity from shared heritage.

Funding

This article was funded by the Ministerio de Universidades (Spain) Ayudas para la Formación de Profesorado Universitario (FPU), grant number FPU21/05700, as part of a predoctoral research project. Besides, this research project was funded by State Investigation Agency, grant number “PID2019-106539RB100” and by the Ministry of Science and Innovation and State Investigation Agency, grant number “PDC2022-133460-I00”.

Data Availability Statement

References

- Pishghadam, R.; Golzar, J.; Miri, M.A. A New Conceptual Framework for Teacher Identity Development. Front. Psychol. 2022. 13: 876395. [CrossRef]

- Cobb, D. J. Initial teacher education and the development of teacher identity. In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education M. A. Peters (Ed.). Springer. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O.; Marín-Cepeda, S. Nudos Patrimoniales. Análisis de los vínculos de las personas con el patrimonio personal. Arte, individuo y sociedad, 2018, vol. 30, núm. 3, pp. 483-500. [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.; Castro, B. La sensibilización a partir del patrimonio cultural. En Buscando formas de enseñar: investigar para innovar en didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, E. López Torres, C. R. García y M. Sánchez (Eds.), 2018: 975-984. Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid. ISBN 978-84-8448-958-0.

- Lesmes, D.; Estella, I.; Avendaño, L. Performance en el museo : el museo como performance : [modelos y prácticas para salir y entrar en la institución]. Ediciones asimétricas: Madrid, 2022. 2022; ISBN 978-84-19050-58-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J. G. Shaping A Professional Identity: Stories Of Educational Practice (Editors: F. Michael Connelly & D. Jean Clandinin)”. McGill Journal of Education / Revue Des Sciences De l’éducation De McGil, 1999, 34 (002). Montreal, QC. Available online: https://mje.mcgill.ca/article/view/8478.

- Fontal, O. La educación patrimonial. Teoría y práctica en el aula, el museo e Internet. Trea. 2003. ISBN 84-9704-099-6.

- Scolari, A. Scolari, A. Narrativas transmedia. Cuando todos los medios cuentan. Deusto: Barcelona, 2013. ISBN 9788423413362.

- Sedeño Valdellós, A.; Guarinos, V. El cuerpo audiovisualizado en la realización del vídeo musical contemporáneo. Atenea (Concepción): revista de ciencias, artes y letras, 2021, 523, 139-157. [CrossRef]

- Weinrichter López, A. (Ed.). La forma que piensa. Tentativas en torno al Cine-ensayo. Pamplona. España: Gobierno de Navarra. Departamento de Cultura y Turismo-Institución Príncipe de Viana y Museo Reina Sofía. 2007. ISBN: 978-84-235-2937-7.

- Ledo Andión, M. El cuerpo y la cámara. Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, 2020. ISBN: 9788437641010.

- Escaño, C. Arts and the Commons. Practices of Cultural Expropiation in the Age of the Network Superstructure. In Art, Images and Network Culture, J.Martín Prada (Ed.), 2021 (pp. 137-155). McGraw-Hil. Available online: https://bit.ly/3g9faS6.

- Bajardi, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, D. Contribuciones de la educación artística a la construcción de la identidad profesional docente: competencias básicas y comunicativas. Historia y Comunicación Social, 2013, 18, nº febrero: 615-26. [CrossRef]

- Irwin, R. La práctica de la a/r/tografía. Traducido por Diego García. Revista Educación y Pedagogía, 2013, 25, (65-66), pp. 106-113. Available online: https://bit.ly/3CFMdFI.

- Denzin, N.; Lincoln, Y. Manual de investigación cualitativa (4ª ed.). Gedisa, 2012. 978-84-9784-307-2.

- Irwin. R. L. A/r/tography, a metonymic métisaage. In Rita L. Irwin y Alex De Cooson (eds.) A/r/tography: Rendering Self Through Arts-Based Living Inquiry. Pacific Educational: 2004; pp. 27- 38.

- Marín-Viadel, R.; Roldán, J. A/r/tografía e Investigación Educativa Basada en Artes Visuales en el panorama de las metodologías de investigación. Educación Artística. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad, 2019, 31(4), 881-895. [CrossRef]

- Springgay, S.; Irwin, R.; Wilson, S. A/r/tography as Living Inquiry Through Art and Text. Qualitative Inquiry, 2005, 11(6), pp. 897-912. [CrossRef]

- García Roldán, A. El vídeo-ensayo en las metodologías Artísticas de Investigación en Educación. La creación audiovisual como una estructura de indagación en contextos de formación, investigación y producción artística. Communication & Methods, 2020, 2(1), 108-125. [CrossRef]

- Barrera-García, A.; Pastor-Moreno, C.; Prieto-Medel, C.; Marfil-Carmona, R. Desfragmentación y remezcla como estrategia educomunicativa con enfoque de género: propuesta didáctica para la interpretación creativa a partir de la película “After”. En J. Sierra Sánchez y J. Gomes Pinto, Audiovisual e indústrias creativas: presente e futuro, 2021, Volume. 2 (pp. 679-693). McGraw-Hill: Madrid.

- Bajardi, A.; y Álvarez-Rodríguez, D. El cuerpo docente y los procesos de configuración de la identidad profesional. Opción 2015, 31, no. 5: 111-129. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=31045570007.

- De Soto, O. Historia(s) in Hacer historia. Reflexiones desde la práctica de la danza, Denaverán, I. (ed). Cuerpo de Letra: Barcelona, 2010. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11904/1121.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Lo visible y lo invisible. Seguido de: Notas de trabajo. Nueva Visión: Buenos Aires, 2010, ISBN: 978-950-602-609-7.

- Domínguez, J. El fenómeno de la mirada y el concepto de lugar. Una propuesta de aprendizaje basado en proyecto con videocreación e Internet. Educación artística: revista de investigación, 2020, 11, 97-113. [CrossRef]

- Mockler, N. Navigating professional identity as a teacher of history, in Historical Thinking for History Teachers, Allender, T. (Ed.) Routledge: London, 2019. ISBN 9781003115977.

- Schon, D. A. Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions, Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, 1991. ISBN 1-55542-025-7.

- González, G.; Martínez, L. Los Diarios Corporales Docentes como Instrumentos de Reflexión y de Evaluación Formativa en el Prácticum de Formación Inicial del Profesorado. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 2018, 44(2): 185- 204. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, L.; Grinspun, N.; Medina, S.; Oyarzún, C. El cuerpo como dispositivo didáctico en la formación inicial docente en artes visuales para enseñanza secundaria. Educación artística: revista de investigación, 2020, 11, 54-70. [CrossRef]

- Ramon, R.; Arcoba, M. D. La Creación De Conocimiento Compartido Entre Profesorado Y Alumnado a Partir De Narrativas Artísticas Audiovisuales. Observar. Revista Electrónica De Didáctica De Las Artes 2019 (13), 39-60. Available online: https://www.observar.eu/index.php/Observar/article/view/99.

- Murray, C. “From isolation to individualism: Collegiality in the teacher identity narratives of experienced second-level teachers in the Irish context”, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Toffler, A. La tercera ola (A. Martín, trad.). Plaza & Janés: Barcelona, 1981. ISBN: 8401370663. 8401. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).