Submitted:

01 December 2023

Posted:

04 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

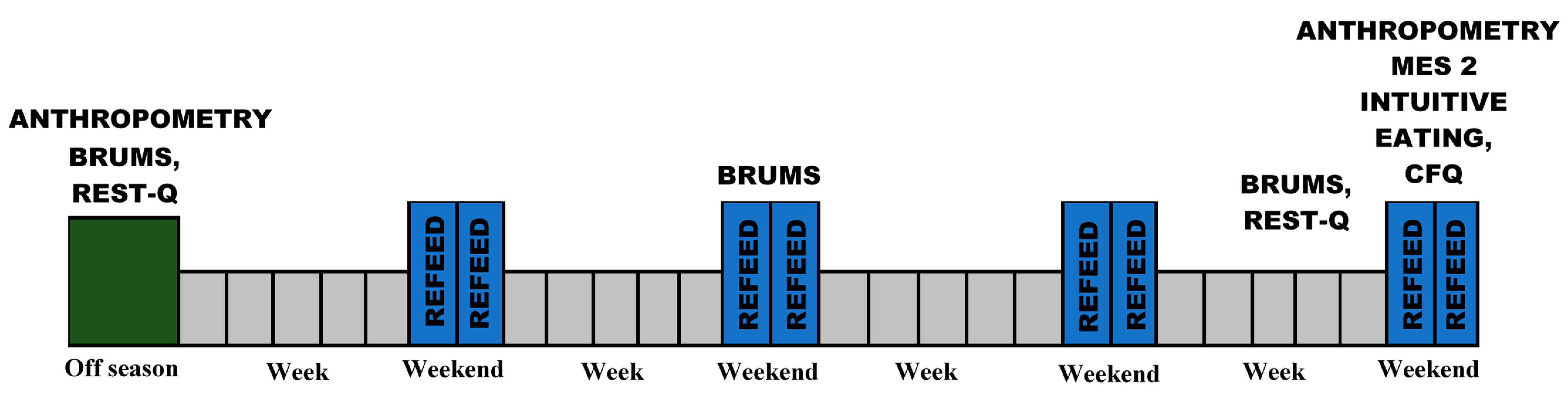

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Anthropometric Date

2.3. Energy Intake

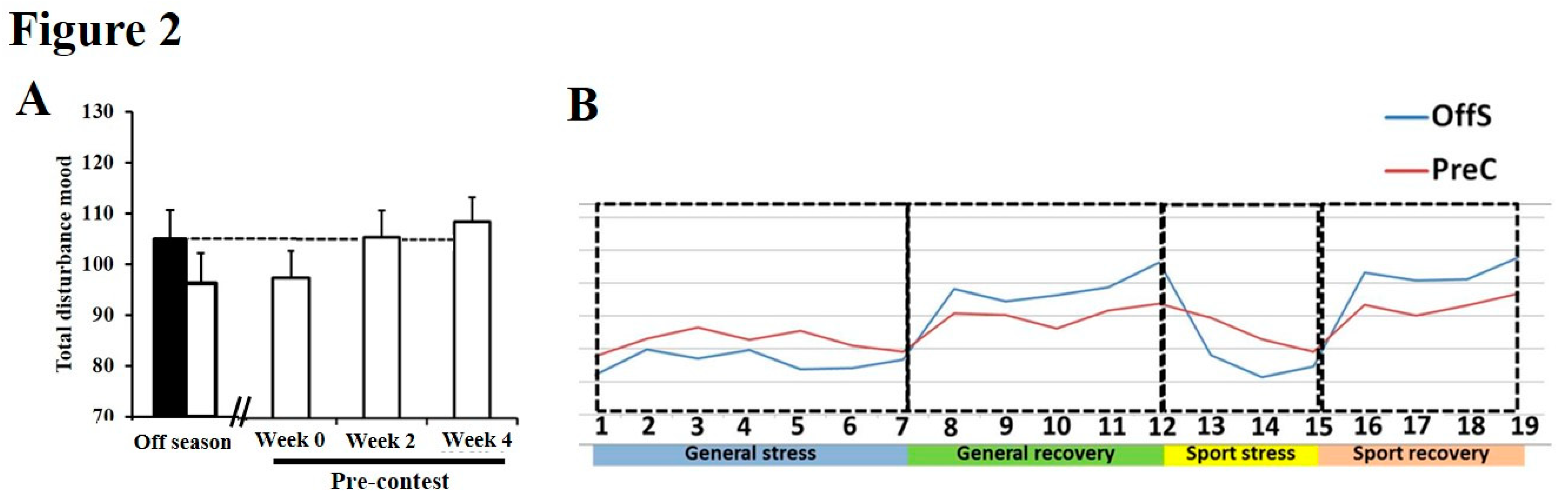

2.4. Psychological Distress and Mood Disturbance

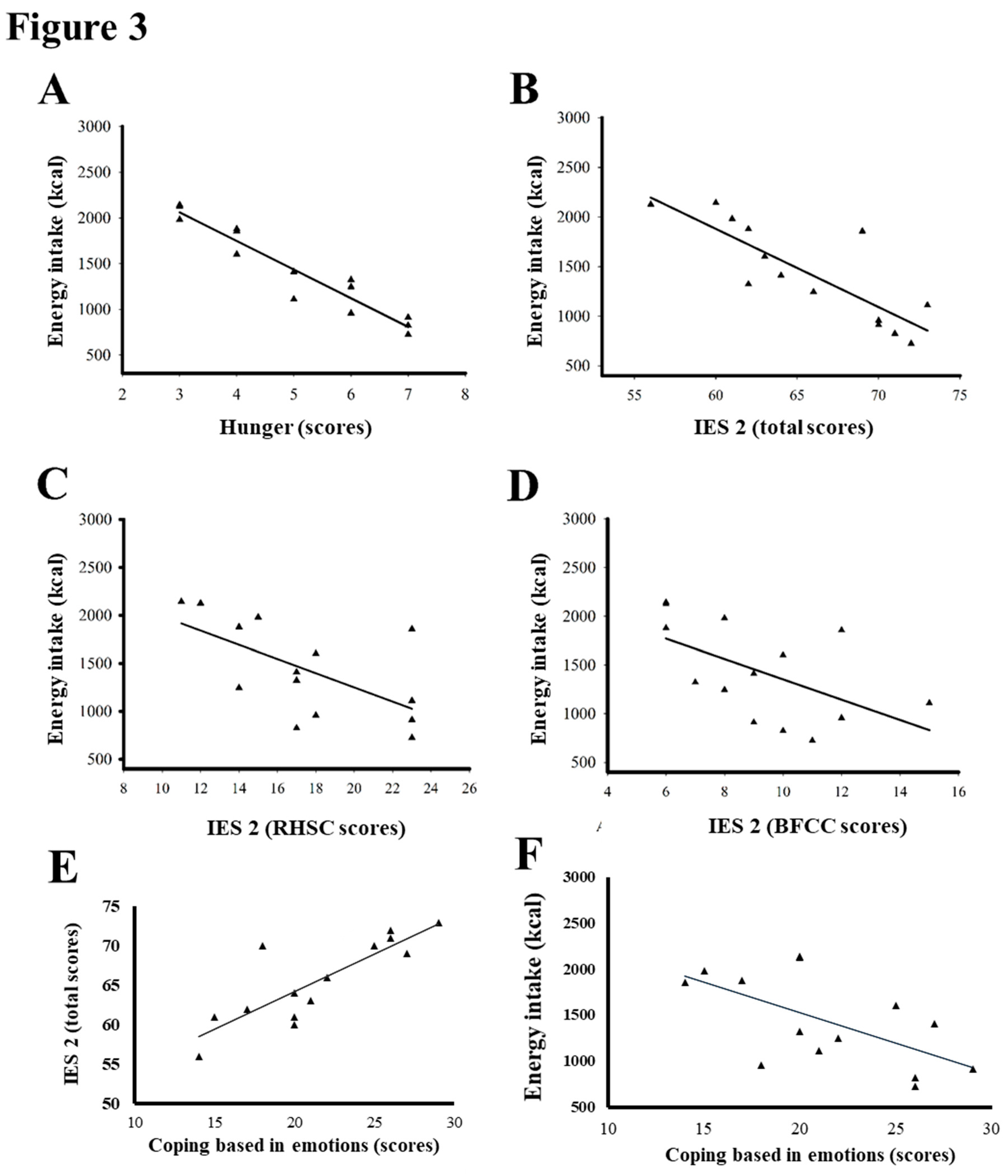

2.5. Adaptive Eating

2.5.1. Mindful Eating

2.5.2. Perception of Hunger and Appetite

2.5.3. Intuitive Eating

2.6. Coping Construct

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alves RC, Prestes J, Enes A, de Moraes WMA, Trindade TB, de Salles BF, et al. Training Programs Designed for Muscle Hypertrophy in Bodybuilders: A Narrative Review. Sports (Basel). 2020;8(11). [CrossRef]

- de Moraes WMAM, de Moura FC, Costa Moraes TCD, Sousa LGO, Rosa TDS, Schoenfeld BJ, et al. Oxidative stress, inflammatory, psychological markers and severity of respiratory infections are negatively affected during the pre-contest period in amateur bodybuilders. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Peos JJ, Norton LE, Helms ER, Galpin AJ, Fournier P. Intermittent Dieting: Theoretical Considerations for the Athlete. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Moura RF, De Moraes WMAM, De Castro BM, Nogueira ALP, Trindade TB, Schoenfeld BJ, et al. Carbohydrate refeed does not modify GVT-performance following energy restriction in bodybuilders. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;43:308-16. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell L, Hackett D, Gifford J, Estermann F, O'Connor H. Do Bodybuilders Use Evidence-Based Nutrition Strategies to Manipulate Physique? Sports (Basel). 2017;5(4). [CrossRef]

- Peos JJ, Helms ER, Fournier PA, Krieger J, Sainsbury A. A 1-week diet break improves muscle endurance during an intermittent dieting regime in adult athletes: A pre-specified secondary analysis of the ICECAP trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0247292. [CrossRef]

- Spendlove J, Mitchell L, Gifford J, Hackett D, Slater G, Cobley S, et al. Dietary Intake of Competitive Bodybuilders. Sports Med. 2015;45(7):1041-63. [CrossRef]

- Pila E, Mond JM, Griffiths S, Mitchison D, Murray SB. A thematic content analysis of #cheatmeal images on social media: Characterizing an emerging dietary trend. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(6):698-706. [CrossRef]

- Helms ER, Prnjak K, Linardon J. Towards a Sustainable Nutrition Paradigm in Physique Sport: A Narrative Review. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(7). [CrossRef]

- Yoon C, Jacobs DR, Duprez DA, Dutton G, Lewis CE, Neumark-Sztainer D, et al. Questionnaire-based problematic relationship to eating and food is associated with 25 year body mass index trajectories during midlife: The Coronary Artery Risk Development In Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(1):10-7. [CrossRef]

- Hickey A, Shields D, Henning M. Perceived Hunger in College Students Related to Academic and Athletic Performance. Education Sciences. 2019;9(3):242. [CrossRef]

- Deroost N, Cserjési R. Attentional avoidance of emotional information in emotional eating. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:172-7. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg T, Allebrandt KV, Merrow M, Vetter C. Social jetlag and obesity. Curr Biol. 2012;22(10):939-43. [CrossRef]

- Jackson AS, Pollock ML. Practical Assessment of Body Composition. Phys Sportsmed. 1985;13(5):76-90. [CrossRef]

- Gomes AC, Landers GJ, Binnie MJ, Goods PSR, Fulton SK, Ackland TR. Body composition assessment in athletes: Comparison of a novel ultrasound technique to traditional skinfold measures and criterion DXA measure. J Sci Med Sport. 2020;23(11):1006-10. [CrossRef]

- de Moraes WMAM, de Almeida FN, Dos Santos LEA, Cavalcante KDG, Santos HO, Navalta JW, et al. Carbohydrate Loading Practice in Bodybuilders: Effects on Muscle Thickness, Photo Silhouette Scores, Mood States and Gastrointestinal Symptoms. J Sports Sci Med. 2019;18(4):772-9.

- Costa, LO, Samulski, DM. (2005). Processo de validação do Questionário de Estresse e Recuperação para Atletas (RESTQ-Sport) na Língua Portuguesa. Rev Bras de Ciência & Movimento. 2005;13(1), 79-86. [CrossRef]

- Rholfs, ICPM. 2003. Validação do teste BRUMS para avaliação de humor em atletas e não-atletas brasileiros. Doctoral thesis. Florianópolis: Santa Catarina: Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, 111p.

- Framson C, Kristal AR, Schenk JM, Littman AJ, Zeliadt S, Benitez D. Development and validation of the mindful eating questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(8):1439-44. [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga M, Figueiredo M, Timerman F, editors. Nutrição comportamental. São Paulo: Manole;2019.

- da Silva WR, Neves AN, Ferreira L, Campos JADB, Swami V. A psychometric investigation of Brazilian Portuguese versions of the Caregiver Eating Messages Scale and Intuitive Eating Scale-2. Eat Weight Disord. 2020;25(1):221-30. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, FSA. Adaptação e validação da escala de Coping Function Questionnaire (CFQ) para o contexto esportivo brasileiro. 2019. Masters Dissertation. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina.118p.

- Campbell BI, Aguilar D, Colenso-Semple LM, Hartke K, Fleming AR, Fox CD, et al. Intermittent Energy Restriction Attenuates the Loss of Fat Free Mass in Resistance Trained Individuals. A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2020;5(1). [CrossRef]

- Syed-Abdul MM, Dhwani S, Jason DW. Effects of self-implemented carbohydrate cycling and moderate to high intensity resistance exercise on body fat in body builders. Gazz Med Ital Archivio Sci. Med. 2019, 178, 221–224.

- Peos JJ, Helms ER, Fournier PA, Ong J, Hall C, Krieger J, et al. Continuous versus Intermittent Dieting for Fat Loss and Fat-Free Mass Retention in Resistance-trained Adults: The ICECAP Trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(8):1685-98. [CrossRef]

- Bauer P, Majisik A, Mitter B, Csapo R, Tschan H, Hume P, et al. Body Composition of Competitive Bodybuilders: A Systematic Review of Published Data and Recommendations for Future Work. J Strength Cond Res. 2023;37(3):726-32. [CrossRef]

- Helms ER, Aragon AA, Fitschen PJ. Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11:20. [CrossRef]

- Roberts BM, Helms ER, Trexler ET, Fitschen PJ. Nutritional Recommendations for Physique Athletes. J Hum Kinet. 2020;71:79-108. [CrossRef]

- Herbert BM, Blechert J, Hautzinger M, Matthias E, Herbert C. Intuitive eating is associated with interoceptive sensitivity. Effects on body mass index. Appetite. 2013;70:22-30. [CrossRef]

- Plateau CR, Petrie TA, Papathomas A. Learning to eat again: Intuitive eating practices among retired female collegiate athletes. Eat Disord. 2017;25(1):92-8. [CrossRef]

- Tylka TL, Calogero RM, Daníelsdóttir S. Is intuitive eating the same as flexible dietary control? Their links to each other and well-being could provide an answer. Appetite. 2015;95:166-75. [CrossRef]

- Hickey A, Shields D, Henning M. Perceived Hunger in College Students Related to Academic and Athletic Performance. Education Sciences. 2019;9(3):242. [CrossRef]

- Chica-Latorre S, Buechel C, Pumpa K, Etxebarria N, Minehan M. After the spotlight: are evidence-based recommendations for refeeding post-contest energy restriction available for physique athletes? A scoping review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2022;19(1):505-28. [CrossRef]

| Food intake | Weeks | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Protein (g/kg) | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| % energy | 38.0 ± 4 | 40 ± 4 | 36 ± 4 | 37 ± 4 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 236 ± 36 | 242 ± 29 | 231 ± 32 | 249 ± 36 |

| % energy | 35 ± 4 | 35 ± 3 | 35 ± 3 | 35 ± 4 |

| Fats (g) | 83 ± 6 | 78 ± 6 | 88 ± 7 | 88 ± 6 |

| % energy | 27 ± 4 | 25 ± 4 | 29 ± 5 | 28 ± 3 |

| Energy intake (kcal) | 2729 ± 132 | 2801 ± 148 | 2746 ± 129 | 2731 ± 124 |

| Anthropometric parameter | Pre | Post | ||

| Height (cm) | 173.0 ± 0.1 | 173.1 ± 0.1 | ||

| Body mass (kg) | 85.6 ± 6.8 | 83.5 ± 5.9* | ||

| Body fat (%) | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.2* | ||

| Fat mass (kg) | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 5.0 ± 0.2* | ||

| Lean body mass (kg) | 79.4 ± 5.9 | 78.4 ± 5.6* | ||

| Training caractheristics | ||||

| Resistance training | ||||

| Days/ week | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 0.2 * | ||

| Minutes/ week | 517.5 ± 23.2 | 635.5 ± 29.2 * | ||

|

Poses training Days/ week Minutes/ week Aerobic exercise |

4.6 ± 0.8 79.3 ± 10.7 |

5.0 ± 0.6 * 89.3 ± 12.5* |

||

| Days/ week | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.2 * | ||

| Minutes/ week | 261.4 ± 35.4 | 327.4 ± 30.2 * | ||

| Sleep | ||||

| Hours/ day | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | ||

| Social jet leg | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | ||

| MES 2 scale | |

| Consciousness | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| Distraction | 2.3 ± 0.2 |

| Disinhibition | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| Emotional response | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| External influences | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| Total score | 9.5 ± 0.7 |

| Perception of hunger/ appetite | 4.8 ± 0.4 |

| IES 2 scale | |

| Unconditional permission to eat | 14.9 ± 0.6 |

| Eating for physical rather than emotional reasons | 24.0 ± 0.6 |

| Confidence in hunger and satiety signals | 17.5 ± 1.1 |

| Body-food congruence | 9.2 ± 0.7 |

| Total scores | 65.9 ± 1.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).