Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

05 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Familiarity and Image

2.2. Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Loyalty Intentions

2.3. Moderating Role of Visitor Involvement

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Context: The Qingdao International Beer Festival

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Collection and Sample Characteristic

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Variance

4.2. Measurement Model Analysis

4.3. Structural Equation Modelling

4.4. Moderation Analysis

5. Conclusion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Social Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Brand Value of the Qingdao International Beer Festival and the Tsingtao Beer

Appendix B. Tsingtao Beer Products

References

- Chi, X.; Meng, B.; Zhou, H.; Han, H. Cultivating and disseminating a festival image: The case of the Qingdao International Beer Festival. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2022, 39, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C. Assessing the Compensatory Potentiality of Hot Spring Tourism in the COVID-19 Post-Pandemic Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Patuleia, M.; Silva, R.; Estêvão, J.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Post-pandemic recovery strategies: Revitalizing lifestyle entrepreneurship. J. Pol. Res. Tour. Leis. Events. 2022, 14, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camprubí, R.; Gassiot-Melian, A. Advances in Tourism Image and Branding. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Meng, B.; Lee, H.; Chua, B.L.; Han, H. Pro-environmental employees and sustainable hospitality and tourism businesses: Exploring strategic reasons and global motives for green behaviors. Bus. Strategy. Environ. 2023, 32, 4167–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; So, K.K.F. Two decades of customer experience research in hospitality and tourism: A bibliometric analysis and thematic content analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Luo, J.M.; Yao, R. How fear of COVID-19 affects the behavioral intention of festival participants—A case of the HANFU Festival. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health. 2022, 19, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topcuoglu, E.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Green message strategies and green brand image in a hotel context. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, B.; Klaniczay, J. Branding Built Heritage through Cultural Urban Festivals: An Instagram Analysis Related to Sustainable Co-Creation, in Budapest. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, I.Y.; Yu, H.A. How festival brand equity influences loyalty: the mediator effect of satisfaction. J. Con Event. Tour. 2022, 23, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.; Park, D.B.; Petrick, J.F. Festival tourists’ loyalty: The role of involvement in local food festivals. J. Hosp.Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgiç, A.; Birdir, K. Key success factors on loyalty of festival visitors: the mediating effect of festival experience and festival image. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2020, 16, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Bi, J.W. Perceived crowding and festival experience: The moderating effect of visitor-to-visitor interaction. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Han, H.; Kim, S. Protecting yourself and others: festival tourists’ pro-social intentions for wearing a mask, maintaining social distancing, and practicing sanitary/hygiene actions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1915–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowen, I. The transformational festival as a subversive toolbox for a transformed tourism: lessons from Burning Man for a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 2020. 22, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Kang, H.C. Storytelling festival participation and tourists’ revisit intention. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 968472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossowska, L.; Janiszewska, D.; Kwiatkowski, G.; Kloskowski, D. The Impact of Local Food Festivals on Rural Areas’ Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, G.L.; Liu, Y.; Presenza, A.; Moyle, C.L. How does familiarity shape destination image and loyalty for visitors and residents? J. Vac. Mark. 2021, 27, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Deng, F. Innovation and authenticity: Constructing tourists’ subjective well-being in festival tourism. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 950024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, Y.; Kumail, T.; Pan, L. Tourism destination brand equity, brand authenticity and revisit intention: the mediating role of tourist satisfaction and the moderating role of destination familiarity. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 751–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhzady, S.; Çakici, C.; Olya, H.; Mohajer, B.; Han, H. Couchsurfing involvement in non-profit peer-to-peer accommodations and its impact on destination image, familiarity, and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ivkov, M.; Kim, S.S. Destination loyalty explained through place attachment, destination familiarity and destination image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Role of halal-friendly destination performances, value, satisfaction, and trust in generating destination image and loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Wang, Y.; Iqbal, K.; Han, H. Nature-based solutions, mental health, well-being, price fairness, attitude, loyalty, and evangelism for green brands in the hotel context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; Su, X.; Yu, R. Involvement, place attachment, and environmentally responsible behaviour connected with geographical indication products. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 44–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Lee, S.; Ahn, Y.; Kiatkawsin, K. Tourist perceived quality and loyalty intentions towards rural tourism in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. The value chain and competitive advantage. Understand. Bus. Process. 2001, 2, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, B.; Zekiri, J. Measuring customer satisfaction with service quality using American Customer Satisfaction Model (ACSI Model). Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 1, 232–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H. How does involvement affect attendees’ aboriginal tourism image? Evidence from aboriginal festivals in Taiwan. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2021, 24, 2421–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Tussyadiah, I.P. Exploring familiarity and destination choice in international tourism. Asia. Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 17, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Mannan, M. Consumer online purchase behavior of local fashion clothing brands: Information adoption, e-WOM, online brand familiarity and online brand experience. J. Fs. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 22, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, C.-M.; Loi, A.M.-W.; Woon, S. The influence of social media eWOM information on purchase intention. J. Mark. Analytic. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballina, F.J.; Valdes, L.; Del Valle, E. The signalling theory: The Key role of quality standards in the hotels performance. J. Qulty. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Cao, X.; Ge, H.; Liu, Y. How does national image affect tourists’ civilized tourism behavior? The mediating role of psychological ownership. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabbert, E.; Martin, S. Aspects influencing the cognitive, affective and conative images of an arts festival. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tanford, S.; Jung, S. Festival attributes and perceptions: A meta-analysis of relationships with satisfaction and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunel, M.C.; Erkurt, B. Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Website of the Qingdao International Beer Festival. Retrieve from. http://qingdaointernationalbeerfestival.com/qingdao_festival.html (accessed on 17 November 23).

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of consumer expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An assessment of the image of mexico as a vacation destination and the influence of geographical location upon that image. J. Travel. Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoğlu, B.B.; Shi, F.; Okumus, B. Communication sources, local food consumption, and destination visit intention of travellers. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2023, 26, 1763–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Olya, H.G.; Kim, W. Exploring halal-friendly destination attributes in South Korea: Perceptions and behaviors of Muslim travelers toward a non-Muslim destination. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Duarte, P.A.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. The contribution of cultural events to the formation of the cognitive and affective images of a tourist destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, K.M.; Stylidis, D.; Ivkov, M. Explaining conative destination image through cognitive and affective destination image and emotional solidarity with residents. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 917–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.C.; Scott, N. Food experience, place attachment, destination image and the role of food-related personality traits. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Han, H. Exploring slow city attributes in Mainland China: Tourist perceptions and behavioral intentions toward Chinese Cittaslow. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, S.; Papadopoulos, N. Of products and tourism destinations: An integrative, cross-national study of place image. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Petrick, J.F. The effect of celebrity on brand awareness, perceived quality, brand image, brand loyalty, and destination attachment to a literary festival. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirakranont, R.; Sakdiyakorn, M. Conceptualizing meaningful tourism experiences: Case study of a small craft beer brewery in Thailand. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. 1997, McGraw-Hill.

- Suhartanto, D.; Brien, A.; Primiana, I.; Wibisono, N.; Triyuni, N.N. Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: the role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Curr. Issues. Tour. 2020, 23, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, C.K. Measuring festival quality and value affecting visitors’ satisfaction and loyalty using a structural approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Wu, H.C.; Cheng, C.C. An empirical analysis of synthesizing the effects of festival quality, emotion, festival image and festival satisfaction on festival loyalty: A case study of Macau Food Festival. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Ai, C.H. A study of festival switching intentions, festival satisfaction, festival image, festival affective impacts, and festival quality. Tour. Hosp.Res. 2016, 16, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.K.; Lee, T.; Kang, S. Examining the role of service quality, perceived values, and trust in Macau food festival. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lban, M.O.; Kaşli, M.; Bezirgan, M. Effects of destination image and total perceived value on tourists' behavioral intentions: an investigation of domestic festival tourists. Tour. Anal. 2015, 20, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M.; Cantril, H. The psychology of ego-involvements: Social attitudes and identifications. 1947, John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Broderick, A.J.; Mueller, R.D. A theoretical and empirical exegesis of the consumer involvement construct: The psychology of the food shopper. J. Mark. Theory. Pract. 1999, 7, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lin, S.S.; Zhang, C. Authenticity, involvement, and nostalgia: understanding visitor satisfaction with an adaptive reuse heritage site in urban China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.J.; Yeh, S.S.; TC Huan, T.C. Creating loyalty by involvement among festival goers. In Advances in hospitality and leisure. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 2011, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Sthapit, E.; Björk, P.; Piramanayagam, S. Domestic tourists and local food consumption: Motivations, positive emotions and savouring processes. Annals. Leisure. Res. 2023, 26, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perse, E.M. Involvement with local television news: Cognitive and emotional dimensions. Hum. Comm. Res. 1990, 16, 556–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.E.; Dimanche, F. Leisure involvement revisited: Drive properties and paradoxes. J. Leis. Res. 1999, 31, 122–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, W.; Kim, J.J. Application of the value-belief-norm model to environmentally friendly drone food delivery services: The moderating role of product involvement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32(5), 1775–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggraeni, A.D.; Hurriyati, R.; Wibowo, L.A.; Gaffar, V. Tourists involvement influence on behavioral intention through tourist perceived value on spa tourism in West Java. Int. J. Entrep. 2022, 26, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Duncan, J.; Chung, B.W. Involvement, satisfaction, perceived value, and revisit intention: A case study of a food festival. J. Culinary. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.A.; Shapoval, V.; Semrad, K.; Medeiros, M. Familiarity, involvement, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: the case of an African-American cultural festival. Int.J. Event. Festival Manag. 2022, 13, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, E.; Shu, F.; Pan, T. The application of enduring involvement theory in the development of a success model for a craft beer and food festival. Int.J. Event. Festival Manag. 2020, 11, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingdao Municipal Culture and Tourism Bureau. Retrieve from. http://whlyj.qingdao.gov.cn/wlzy/jqhd/202112/t20211227_4142250.shtml (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull, 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, H.H. Modern factor analysis. 1967, University of Chicago Press.

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods. 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate data analysis. 2014, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Higher Education.

- Nunally, J. Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). 1978, McGraw-Hill.

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunally, J.C.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rönkkö, M.; Cho, E. An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Org. Res. Methods. 2022, 25, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqbel, M.; Guduru, R.; Harun, A. Testing mediation via indirect effects in PLS-SEM: A social networking site illustration. Data. Anal. Perspect. J. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Comm. Monographs. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candi, M.; Jae, H.; Makarem, S.; Mohan, M. Consumer responses to functional, aesthetic and symbolic product design in online reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 81, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Zhang, J.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, R.G. Integrating self-determined needs into the relationship among product design, willingness-to-pay a premium, and word-of-mouth: a cross-cultural gender-specific study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2018, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Sutherland, I.; Lee, S.K. Determinants of smart tourist environmentally responsible behavior using an extended norm-activation model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale Items | Loading | Mean | SD | Skewness (Std. error) |

Kurtosis (Std. error) |

| Destination familiarity (α = .818) | |||||

| DF1- My familiarity with Qingdao made me more aware of the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .909 | 4.92 | 1.124 | .164 (.135) | -.772 (.268) |

| DF2- My familiarity with Qingdao let me know more information about the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .932 | 4.91 | 1.025 | -.086 (.135) | -.339 (.268) |

| DF3- My experience with Qingdao made me feel interested in attending the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .796 | 5.09 | 1.088 | .004 (.135) | -.794 (.268) |

| Product familiarity (α =.786 ) | |||||

| PF1- My familiarity with Tsingtao Beer made me more aware of the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .841 | 4.94 | 1.093 | .263 (.135) | -.667 (.268) |

| PF2- My familiarity with Tsingtao Beer encouraged me to get to know the Qingdao International Beer Festival better. | .929 | 4.98 | 1.049 | -.031 (.135) | -.533 (.268) |

| PF3- My recognition of Tsingtao Beer has made me more eager to attend the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .867 | 5.02 | 1.128 | .158 (.135) | -.856 (.268) |

| Overall festival image (α =.913 ) | |||||

| OI1- My overall image of the Qingdao International Beer Festival is positive. | .891 | 5.53 | 1.175 | -.493 (.135) | -.149 (.268) |

| OI2- My overall image of the Qingdao International Beer Festival is preferable. | .910 | 5.52 | 1.222 | -.527 (.135) | -.378 (.268) |

| OI3- The overall image I have of the Qingdao International Beer Festival is favorable. | .870 | 5.57 | 1.166 | -.470 (.135) | -.350 (.268) |

| Perceived value (α =.883 ) | |||||

| PV1- Attending the Qingdao International Beer Festival is worth the price. | .831 | 5.14 | 1.116 | -.147 (.135) | -.583 (.268) |

| PV2- Compared to other festivals, attending the Qingdao International Beer Festival is a good deal. | .904 | 5.27 | 1.098 | -.078 (.135) | -.644 (.268) |

| PV3- Attending the Qingdao International Beer Festival offers a good value for money. | .892 | 5.13 | 1.139 | -.078 (.135) | -.613 (.268) |

| Overall satisfaction (α = .888) | |||||

| OS1- Overall, I am satisfied with my trip experience to the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .912 | 5.36 | 1.010 | -.295 (.135) | -.317 (.268) |

| OS2- My decision to attend the Qingdao Beer Festival was a great choice. | .895 | 5.35 | .972 | -.268 (.135) | -.468 (.268) |

| OS3- As a whole, I have really enjoyed myself while attending the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .894 | 5.43 | 1.011 | -.334 (.135) | -.412 (.268) |

| Re-patronage intention (α =.830 ) | |||||

| RPI1- I will attend the Qingdao International Beer Festival again in the near future. | .979 | 5.53 | 1.043 | -.277 (.135) | -.698 (.268) |

| RPI2- I am willing to attend the Qingdao International Beer Festival again in the near future. | .945 | 5.74 | .931 | -.187 (.135) | -.872 (.268) |

| RPI3- I plan to attend the Qingdao International Beer Festival again in the near future. | .885 | 5.84 | .991 | -.442 (.135) | -.607 (.268) |

| Recommendation intention (α =.889 ) | |||||

| RCI1- I will say positive experiences about the Qingdao International Beer Festival to others. | .846 | 5.61 | 1.022 | -.170 (.135) | -.950 (.268) |

| RCI2- I will recommend the Qingdao International Beer Festival to family/friends/others. | .949 | 5.55 | 1.091 | -.233 (.135) | -.836 (.268) |

| RCI3- I will encourage family/friends/relatives to attend the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .916 | 5.45 | 1.119 | -.162 (.135) | -.917 (.268) |

| Visitor involvement (α = .818) | |||||

| VI1- Attending the Qingdao International Beer Festival is somewhat of a pleasure to me. | .847 | 5.17 | 1.015 | -.354 (.135) | .095 (.268) |

| VI2- Attending the Qingdao International Beer Festival interests me a lot. | .898 | 5.12 | .992 | -.159 (.135) | -.286 (.268) |

| VI3- I am deeply absorbed in the Qingdao International Beer Festival. | .812 | 5.24 | 1.037 | -.009 (.135) | -.567 (.268) |

| Total Variance Explained | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 13.950 | 24.911 | 24.911 | 13.950 | 24.911 | 24.911 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Destination familiarity | .912 | .570b | .173 | .172 | .177 | .165 | .187 | .262 | |

| Product familiarity | .755a | .911 | .195 | .207 | .221 | .208 | .245 | .187 | |

| Overall festival image | .416 | .442 | .920 | .719 | .755 | .539 | .661 | .513 | |

| Perceived value | .415 | .455 | .848 | .908 | .821 | .584 | .663 | .555 | |

| Overall satisfaction | .421 | .470 | .869 | .906 | .928 | .667 | .774 | .630 | |

| Re-patronage intention | .406 | .456 | .734 | .764 | .817 | .942 | .750 | .445 | |

| Recommendation intention | .432 | .495 | .813 | .814 | .880 | .866 | .931 | .534 | |

| Visitor involvement | .512 | .507 | .716 | .745 | .794 | .667 | .731 | .889 | |

| AVE | .776 | .774 | .793 | .768 | .811 | .844 | .818 | .728 | |

| Mean | 4.97 | 4.98 | 5.54 | 5.18 | 5.38 | 5.70 | 5.54 | 5.18 | |

| Standard deviation | 1.118 | 1.090 | 1.188 | 1.118 | .998 | .988 | 1.077 | 1.015 | |

|

Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ² = 539.117, df = 220, χ² /df = 2.451; p < .001, RMSEA = .065; CFI = .963; IFI = .964; TLI = .954. | |||||||||

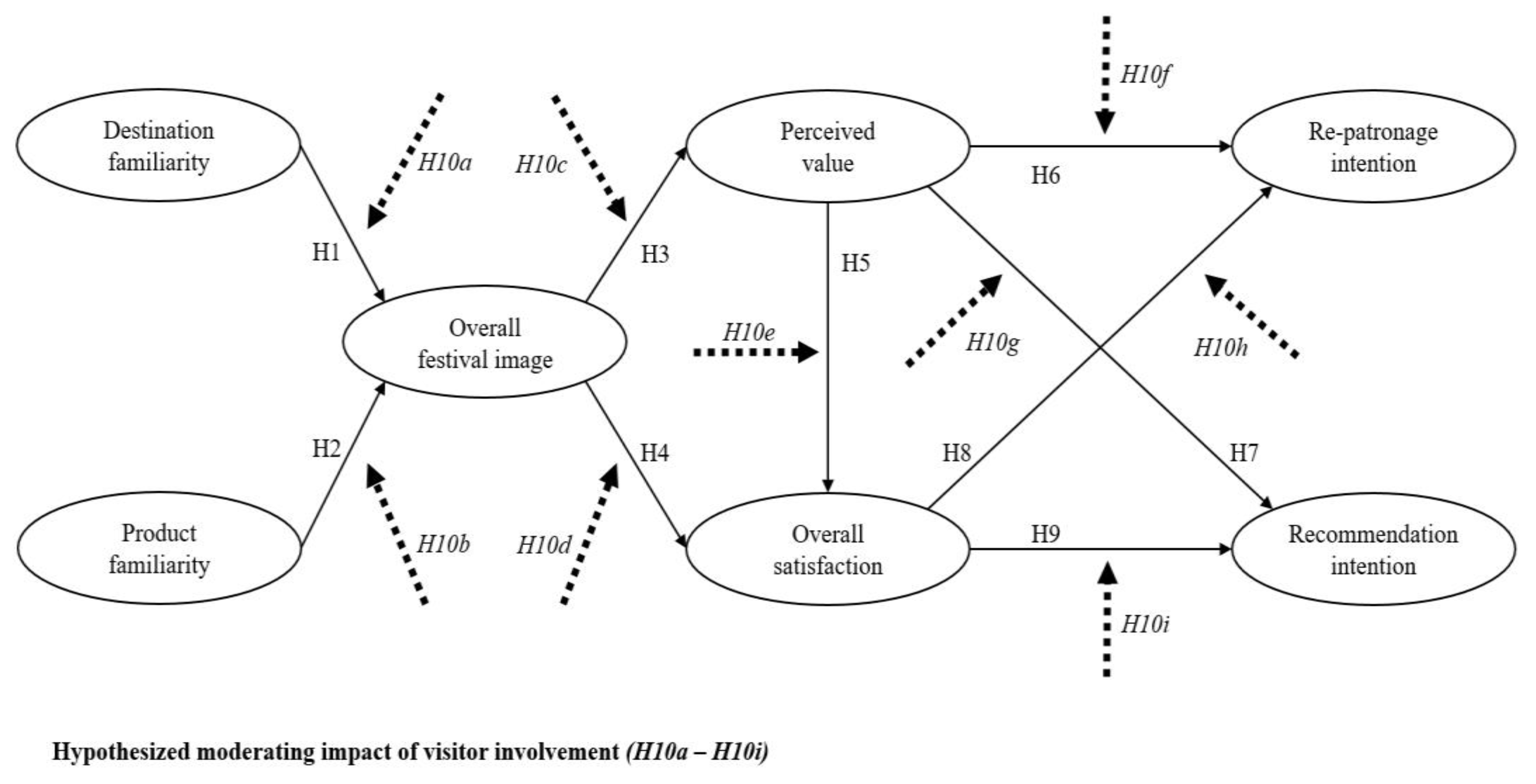

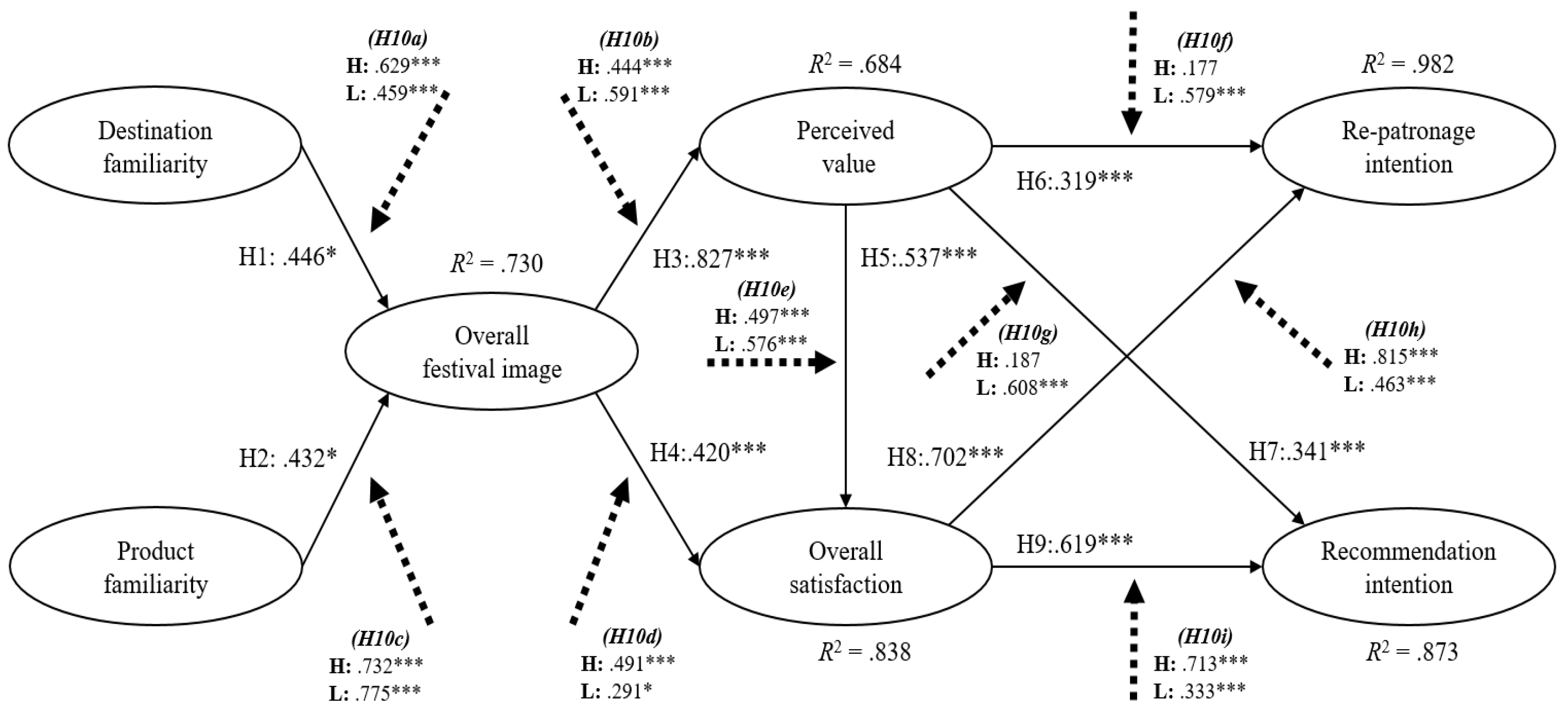

| Hypothesis | Coefficient | t-value | Supported |

| H1: Destination familiarity → Overall festival image | .446 | 3.005* | YES |

| H2: Product familiarity → Overall festival image | .432 | 2.870* | YES |

| H3: Overall festival image → Perceived value | .827 | 15.244*** | YES |

| H4:Overall festival image → Overall satisfaction | .420 | 5.781*** | YES |

| H5: Perceived value → Overall satisfaction | .537 | 6.996*** | YES |

| H6: Perceived value → Re-patronage intention | .319 | 3.327*** | YES |

| H7: Perceived value → Recommendation intention | .341 | 3.478*** | YES |

| H8: Overall satisfaction → Re-patronage intention | .702 | 7.014*** | YES |

| H9: Overall satisfaction → Recommendation intention | .619 | 6.157*** | YES |

|

Total variance explained: R2 for overall festival image = .730; R2 for perceived value = .684; R2 for overall satisfaction = .838; R2 for re-patronization intention = .982; R2 for recommendation intention = .873 | |||

|

Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ² = 296.563, df = 179, χ² /df = 1.657; p < .001, RMSEA = .045; CFI = .979; IFI = .979; TLI = .975. | |||

| On | ||||

| Indirect effect of | Perceived value | Overall satisfaction |

Re-patronage intention |

Recommendation intention |

| Destination familiarity | .369** | .386** | .389** | .365** |

| Product familiarity | .357** | .373** | .376** | .353** |

| Overall festival image | - | .444** | .871** | .817** |

| Perceived value | - | - | .377** | .332** |

| Paths | High group ( n = 227, mean = 5.63) |

Low group ( n = 101, mean = 4.16) |

Baseline model |

Nested model |

||

| β | t-values | β | t-values | (freely estimated) | (equally restricted) | |

| H10a: DF→ OFI | .629 | 8.616*** | .459 | 4.212*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 697.639 |

| H10b: PF→ OFI | .444 | 6.191*** | .591 | 4.997*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 697.892 |

| H10c: OFI → PV | .732 | 9.687*** | .775 | 6.844*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 696.510 |

| H10d: OFI → OS | .491 | 5.643*** | .291 | 2.087*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 696.870 |

| H10e: PV → OS | .497 | 5.427*** | .576 | 3.906*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 698.384 |

| H10f: PV → RPI | .177 | 1.223 | .579 | 3.850*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 702.224 |

| H10g: PV → RCI | .187 | 1.306 | .608 | 4.020*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 703.191 |

| H10h: OS → RPI | .815 | 5.223*** | .463 | 3.256*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 700.936 |

| H10i: OS → RCI | .713 | 4.715*** | .333 | 2.416*** | χ² (358) = 696.443 | χ² (359) = 700.881 |

|

Baseline model Goodness-of-fit indices: χ² = 696.443, df = 358, χ² /df = 1.945; p < .001, RMSEA = .054; CFI = .930; IFI = .931; TLI = .918. | ||||||

|

Chi-square difference test: △x2 (1) = 1.960, p > .05 H10a: not supported △x2 (1) = 1.449, p > .05 H10b: not supported △x2 (1) = 0.067, p > .05 H10c: not supported △x2 (1) = 0.427, p > .05 H10d: not supported △x2 (1) = 1.941, p > .05 H10e: not supported △x2 (1) = 5.781, p < .05 H10f: supported (Groups are different at the model level) △x2 (1) = 6.748, p < .01 H10g: supported (Groups are different at the model level) △x2 (1) = 4.493, p < .05 H10h: supported (Groups are different at the model level) △x2 (1) = 4.438, p < .05 H10i: supported (Groups are different at the model level) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).