Submitted:

07 December 2023

Posted:

07 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Animal treatments

Morphine Treatment:

ART treatment:

2.3. Nociceptive testing

Tail flick

Von Frey

2.4. 16S rRNA gene sequencing

2.5. Microbiome sequencing data analysis

2.6. Statistical analysis and diversity metrics

3. Results

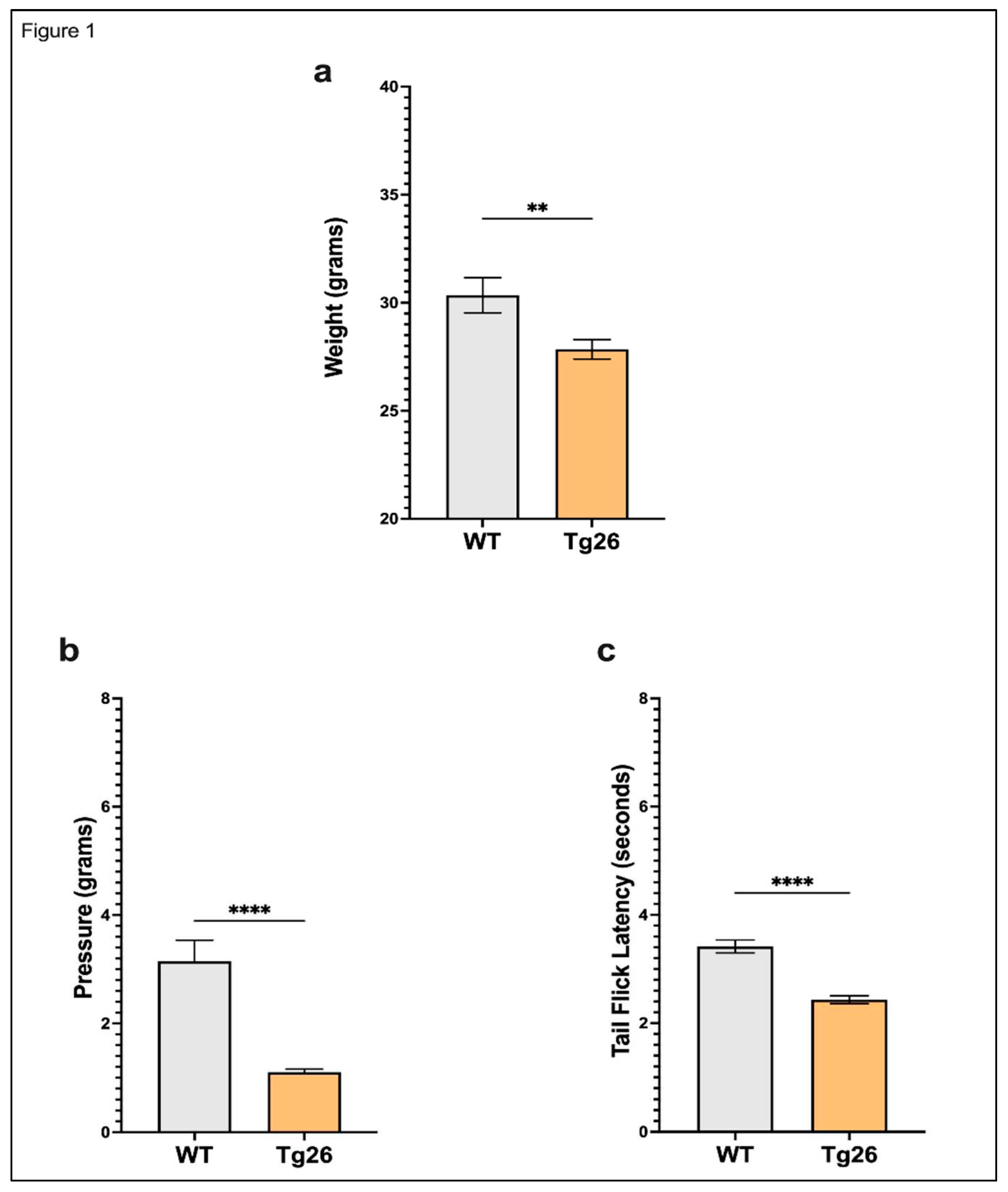

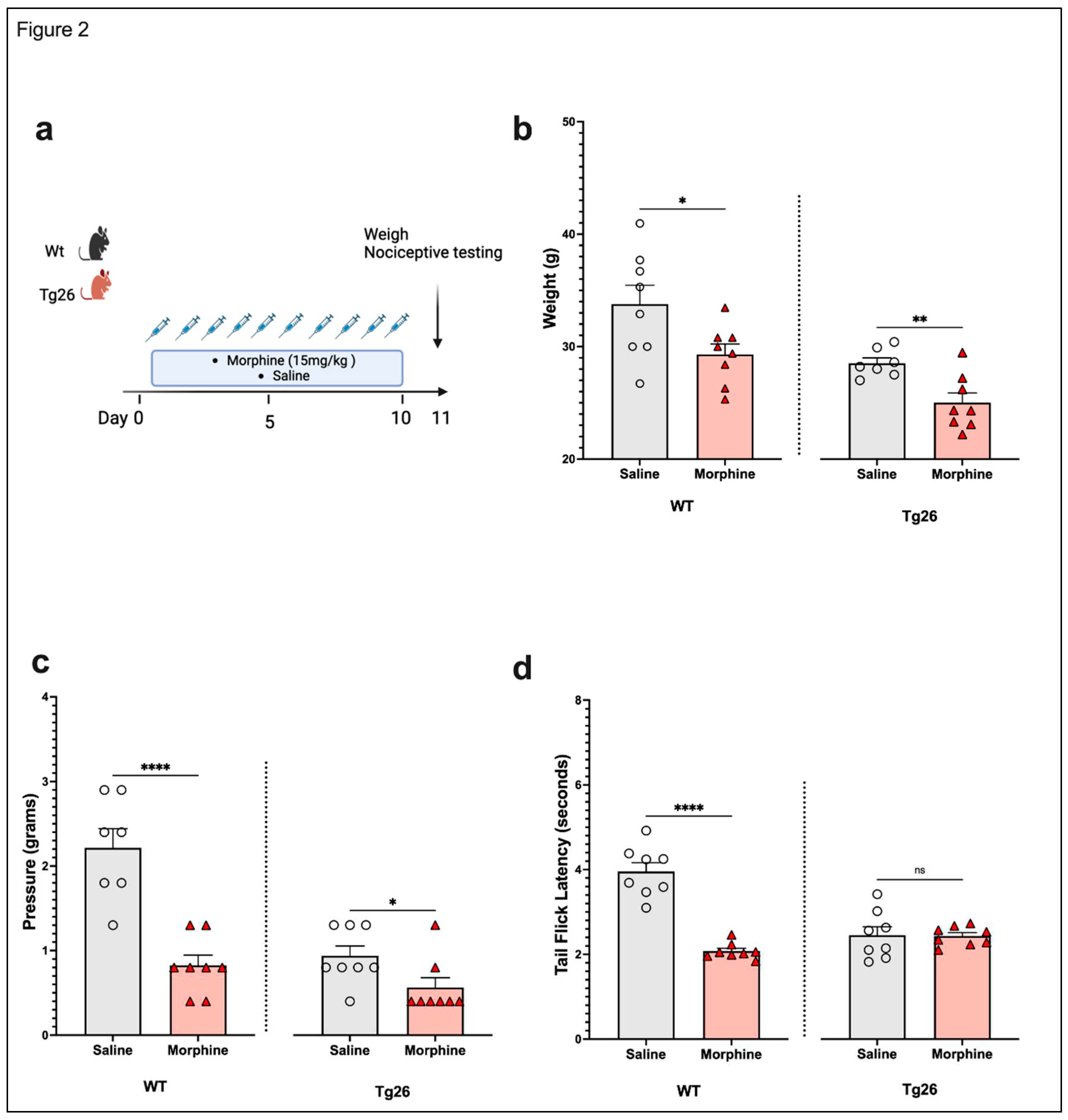

3.1. Chronic morphine treatment worsened the development of peripheral neuropathy through mechanical pain pathways in Tg26 mice compared to WT

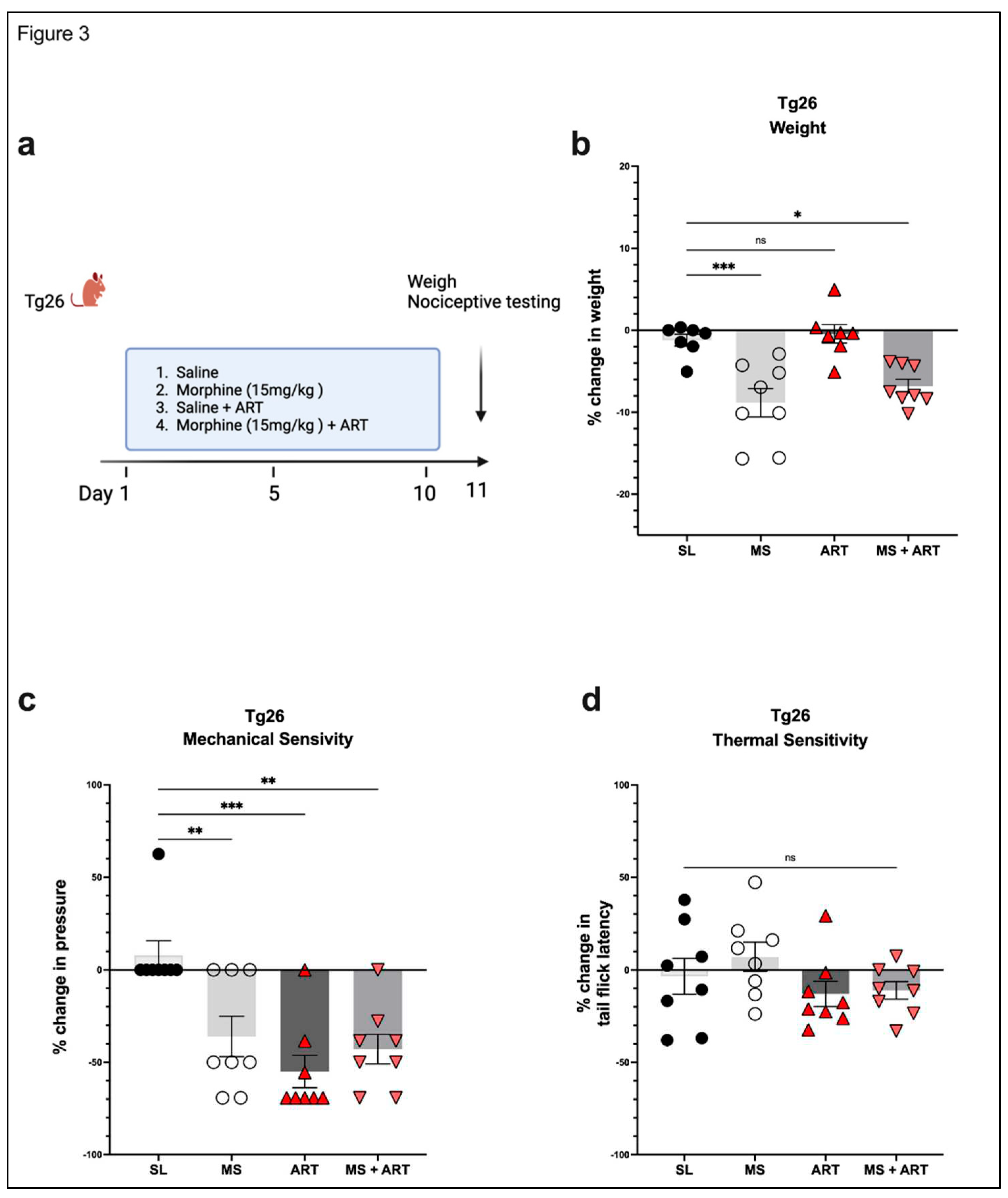

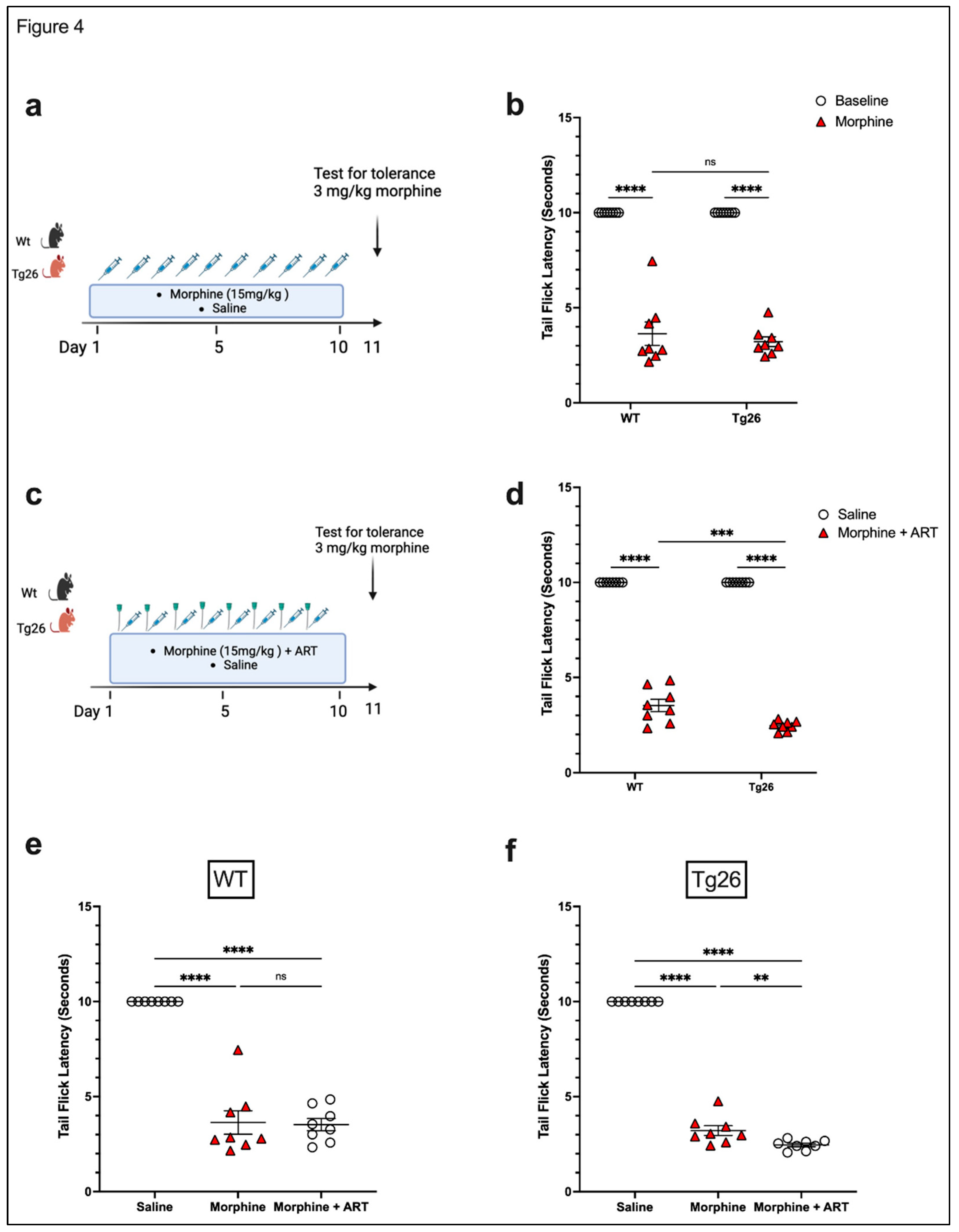

3.2. ART induced peripheral neuropathy through mechanical pain pathways and worsened analgesic tolerance to morphine in Tg26 mice.

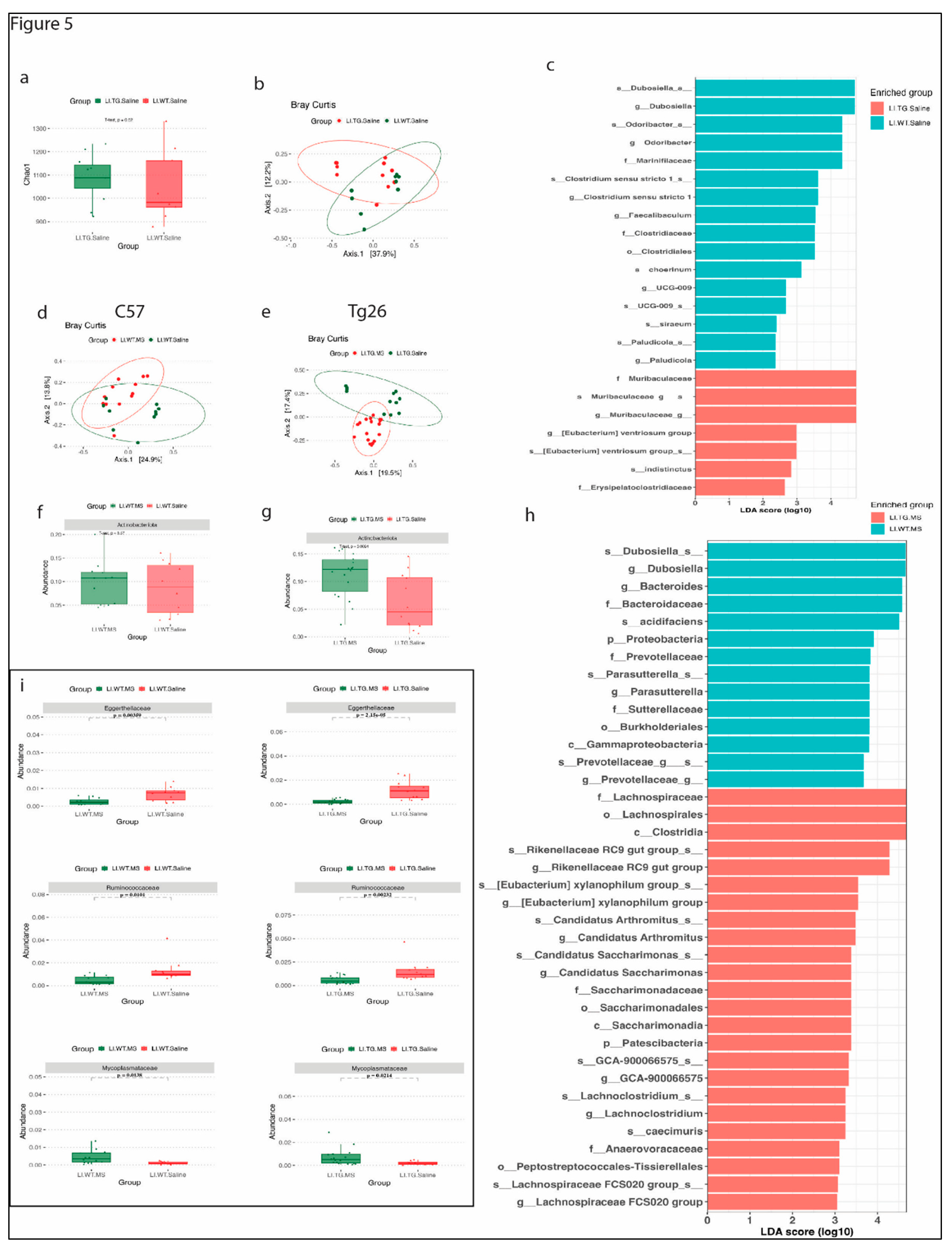

3.3. Distinct bacterial community are observed between WT and Tg26 mice before and after morphine treatment.

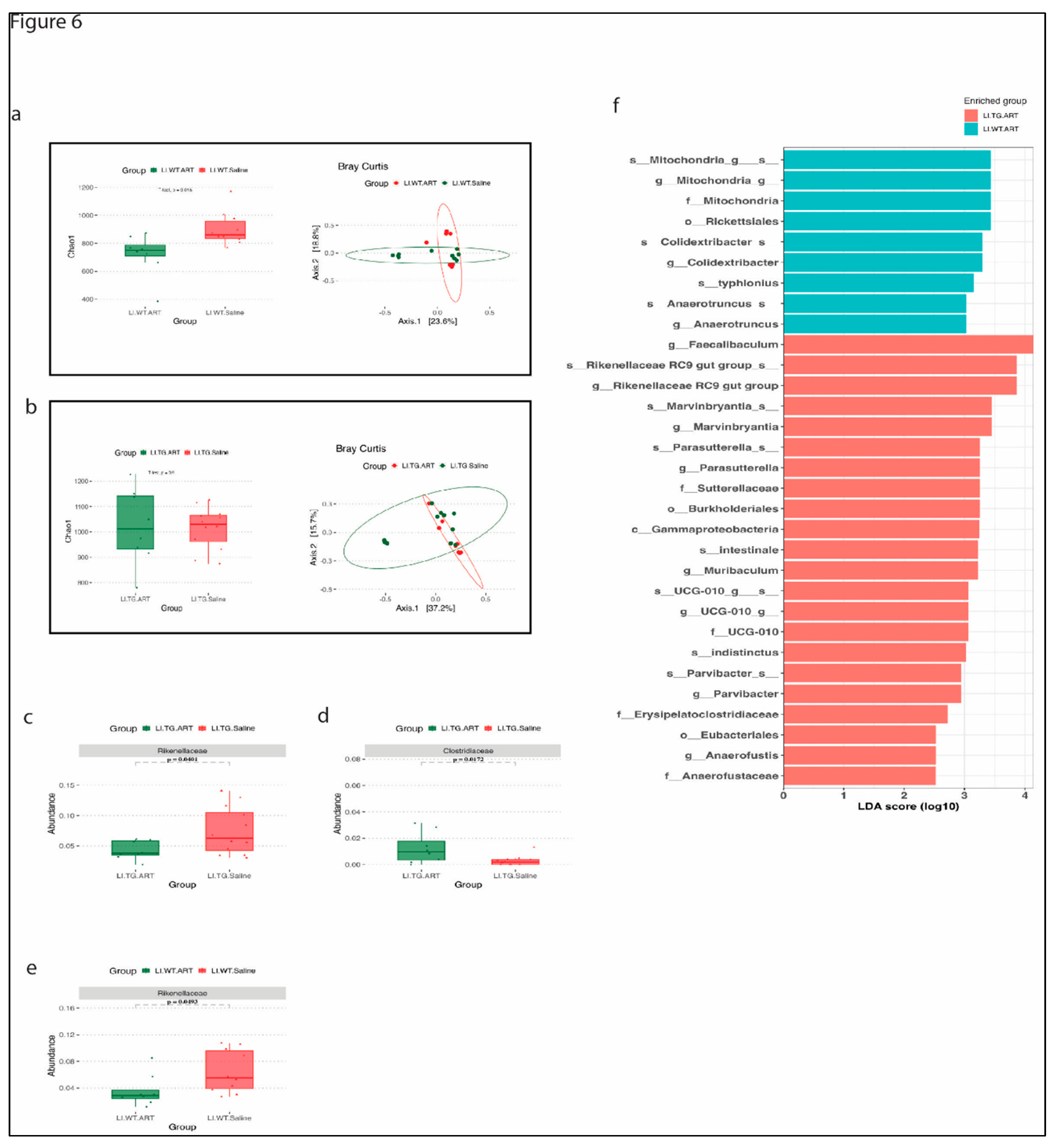

3.4. ART treatment modulates the gut microbiome in WT and Tg26 mice.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- C. M. Centner, K. J. Bateman, and J. M. Heckmann, “Manifestations of HIV infection in the peripheral nervous system,” The Lancet Neurology, vol. 12, no. 3. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Aziz-Donnelly and T. B. Harrison, “Update of HIV-Associated Sensory Neuropathies,” Current Treatment Options in Neurology, vol. 19, no. 10. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Schütz and J. Robinson-Papp, “Hiv-related neuropathy: Current perspectives,” HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, vol. 5. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. K. Anastasi and A. M. Pakhomova, “Assessment and Management of HIV Distal Sensory Peripheral Neuropathy: Understanding the Symptoms,” Journal for Nurse Practitioners, vol. 16, no. 4, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Tumusiime, F. Venter, E. Musenge, and A. Stewart, “Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy and its associated demographic and health status characteristics, among people on antiretroviral therapy in Rwanda,” BMC Public Health, vol. 14, no. 1, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Ellis et al., “Continued high prevalence and adverse clinical impact of human immunodeficiency virus-associated sensory neuropathy in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: The CHARTER study,” Arch Neurol, vol. 67, no. 5, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Dorsey and P. G. Morton, “HIV peripheral neuropathy: Pathophysiology and clinical implications,” AACN Advanced Critical Care, vol. 17, no. 1. 2006.

- T. J. C. Phillips, C. L. Cherry, S. Cox, S. J. Marshall, and A. S. C. Rice, “Pharmacological treatment of painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials,” PLoS One, vol. 5, no. 12, 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Krashin, J. O. Merrill, and A. M. Trescot, “Opioids in the management of HIV-related pain.,” Pain physician, vol. 15, no. 3 Suppl. 2012. [CrossRef]

- B. Liu, X. Liu, and S. J. Tang, “Interactions of opioids and HIV infection in the pathogenesis of chronic pain,” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 7, no. FEB. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Banerjee et al., “Opioid-induced gut microbial disruption and bile dysregulation leads to gut barrier compromise and sustained systemic inflammation,” Mucosal Immunol, vol. 9, no. 6, 2016. [CrossRef]

- I. Vujkovic-Cvijin et al., “Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is associated with HIV disease progression and tryptophan catabolism,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 5, no. 193, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Brenchley et al., “Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection,” Nat Med, vol. 12, no. 12, 2006. [CrossRef]

- N. G. Sandler et al., “Plasma levels of soluble CD14 independently predict mortality in HIV infection,” Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 203, no. 6, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Kopp et al., “Progressive glomerulosclerosis and enhanced renal accumulation of basement membrane components in mice transgenic for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genes,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 89, no. 5, 1992. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Barbe, R. Loomis, A. M. Lepkowsky, S. Forman, H. Zhao, and J. Gordon, “A longitudinal characterization of sex-specific somatosensory and spatial memory deficits in Tg26 heterozygous mice,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 12 December, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Putatunda et al., “Sex-specific neurogenic deficits and neurocognitive disorders in middle-aged HIV-1 Tg26 transgenic mice,” Brain Behav Immun, vol. 80, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Putatunda, Y. Zhang, F. Li, X. F. Yang, M. F. Barbe, and W. Hu, “Adult neurogenic deficits in HIV-1 Tg26 transgenic mice,” J Neuroinflammation, vol. 15, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Dickie et al., “HIV-associated nephropathy in transgenic mice expressing HIV-1 genes,” Virology, vol. 185, no. 1, 1991. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Deuis, L. S. Dvorakova, and I. Vetter, “Methods used to evaluate pain behaviors in rodents,” Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, vol. 10. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Callahan, P. J. McMurdie, M. J. Rosen, A. W. Han, A. J. A. Johnson, and S. P. Holmes, “DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data,” Nat Methods, vol. 13, no. 7, 2016. [CrossRef]

- P. Yilmaz et al., “The SILVA and ‘all-species Living Tree Project (LTP)’ taxonomic frameworks,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 42, no. D1, 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Quast et al., “The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools,” Nucleic Acids Res, vol. 41, no. D1, 2013. [CrossRef]

- N. Segata et al., “Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation,” Genome Biol, vol. 12, no. 6, 2011. [CrossRef]

- J. Meng et al., “Opioids Impair Intestinal Epithelial Repair in HIV-Infected Humanized Mice,” Front Immunol, vol. 10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Satish, Y. Abu, D. Gomez, R. Kumar Dutta, and S. Roy, “HIV, opioid use, and alterations to the gut microbiome: elucidating independent and synergistic effects,” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 14. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Sagen, D. A. Castellanos, and A. T. Hama, “Antinociceptive effects of topical mepivacaine in a rat model of HIV-associated peripheral neuropathic pain,” J Pain Res, vol. 9, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Guindon, H. Blanton, S. Brauman, K. Donckels, M. Narasimhan, and K. Benamar, “Sex differences in a rodent model of HIV-1-associated neuropathic pain,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 20, no. 5, 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. Toma et al., “Persistent sensory changes and sex differences in transgenic mice conditionally expressing HIV-1 Tat regulatory protein,” Exp Neurol, vol. 358, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Bagdas et al., “Conditional expression of HIV-1 tat in the mouse alters the onset and progression of tonic, inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity in a sex-dependent manner,” European Journal of Pain (United Kingdom), vol. 24, no. 8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Wodarski et al., “Reduced intraepidermal nerve fibre density, glial activation, and sensory changes in HIV type-1 Tat-expressing female mice: Involvement of Tat during early stages of HIV-associated painful sensory neuropathy,” Pain Rep, vol. 3, no. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Xu et al., “Catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism Val158Met is associated with distal neuropathic pain in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy,” AIDS, vol. 33, no. 10, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi, S. Yuan, and S. J. Tang, “Morphine and HIV-1 gp120 cooperatively promote pathogenesis in the spinal pain neural circuit,” Mol Pain, vol. 15, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Zhang, Y. Qiu, and Z. Hua, “The Emerging Perspective of Morphine Tolerance: MicroRNAs,” Pain Research and Management, vol. 2019. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. D. Volkow and A. T. McLellan, “Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain — Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 374, no. 13, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. F. Önen, E. P. Barrette, E. Shacham, T. Taniguchi, M. Donovan, and E. T. Overton, “A Review of Opioid Prescribing Practices and Associations with Repeat Opioid Prescriptions in a Contemporary Outpatient HIV Clinic,” Pain Practice, vol. 12, no. 6, 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Smith, “Treatment considerations in painful HIV-related neuropathy,” Pain Physician, vol. 14, no. 6. 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Ray, S. Sil, M. Kannan, P. Periyasamy, and S. Buch, “Role of the gut-brain axis in HIV and drug abuse-mediated neuroinflammation,” Advances in Drug and Alcohol Research, vol. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, X. Zhao, and J. J. He, “HIV Tat Expression and Cocaine Exposure Lead to Sex- and Age-Specific Changes of the Microbiota Composition in the Gut,” Microorganisms, vol. 11, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. He, Y. Yang, H. Wang, N. Liu, Z. Yang, and S. Li, “Unsaturated alginate oligosaccharides (UAOS) protects against dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis associated with regulation of gut microbiota,” J Funct Foods, vol. 83, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Quraishi et al., “The gut-adherent microbiota of PSC-IBD is distinct to that of IBD,” Gut, vol. 66, no. 2. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Huang, H. Pan, Z. Tan, L. Chen, T. Li, and Y. Liu, “Prevotella histicola Prevented Particle-Induced Osteolysis via Gut Microbiota-Dependent Modulation of Inflammation in Ti-Treated Mice,” Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Camelo-Castillo et al., “Subgingival microbiota in health compared to periodontitis and the influence of smoking,” Front Microbiol, vol. 6, no. FEB, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Ray, A. Narayanan, C. G. Giske, U. Neogi, A. Sönnerborg, and P. Nowak, “Altered Gut Microbiome under Antiretroviral Therapy: Impact of Efavirenz and Zidovudine,” ACS Infect Dis, vol. 7, no. 5, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Ishizaka et al., “Unique Gut Microbiome in HIV Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Suggests Association with Chronic Inflammation,” Microbiol Spectr, vol. 9, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Imahashi et al., “Impact of long-term antiretroviral therapy on gut and oral microbiotas in HIV-1-infected patients,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Villar-García et al., “Impact of probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii on the gut microbiome composition in HIV-treated patients: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 4, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Graf, “The family rikenellaceae,” in The Prokaryotes: Other Major Lineages of Bacteria and The Archaea, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Lin et al., “Yellow Wine Polyphenolic Compound Protects Against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Modulating the Composition and Metabolic Function of the Gut Microbiota,” Circ Heart Fail, vol. 14, no. 10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Peters et al., “A taxonomic signature of obesity in a large study of American adults,” Sci Rep, vol. 8, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Mutlu et al., “A Compositional Look at the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Immune Activation Parameters in HIV Infected Subjects,” PLoS Pathog, vol. 10, no. 2, 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Dinh et al., “Intestinal Microbiota, microbial translocation, and systemic inflammation in chronic HIV infection,” in Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2015. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).