2. Methods

A cross-sectional population-based study was carried out with individuals over 18 years of age, of both sexes, Caboverdeans, who agreed to participate in the study by signing the informed consent form. Data collection took place in October and November 2021, in all municipalities on the island of Santiago - Cape Verde. Individuals with Caboverdean nationality who stayed abroad for more than one year and who arrived on the island of Santiago less than 30 days ago and individuals with any type of disability that may have prevented them from participating were excluded from the study.

The sample size was calculated based on the projection of the population of the island of Santiago for the year 2021, for people over 18 years old, according to the appropriate epidemiological model, considering an estimated prevalence of 50%, a confidence interval of 95% and a standard error of 4%. We arrived at a sample size for the island of Santiago of 599 individuals, distributed proportionally across the various municipalities on the island, whose collection procedure was done at random.

Data were collected in all municipalities on the island of Santiago. Households were selected by systematic sampling with random onset. Contact with individuals always started with an index house from which they were collected from the nearest residences, alternating three or more houses in any direction, whenever possible. In households that had more than one individual who met the inclusion criteria, data collection procedures were applied to all. The data collected were recorded in a questionnaire for further analysis. Data such as age, sex, race, weight, height, risk factors (presence of diabetes, dyslipidemia, heredity, physical activity, smoking habits, history of cerebrocardiovascular events, weight control and blood pressure) were collected.

Regarding the practice of physical exercise, this was quantified by the frequency (how many days per week) and duration (minutes/hours) of the exercise. Smoking habits were measured in terms of the number of cigarettes per day and number of years of use. The consumption of alcoholic beverages was quantified by the number of glasses ingested per day, with or without meals. Regarding a history of cerebrovascular pathologies, it was asked if the individual had an acute myocardial infarction, stroke and/or transient ischemic attack. Regarding heredity, he was asked about the existence of a family member with known cardiac pathology. Regarding the habit of controlling weight and blood pressure, they were asked if they were in the habit of doing the control and how often.

Weight was measured using a digital scale, participants were instructed to step on the scale barefoot, with empty pockets, body erect, arms along the body and face raised.

Height was taken using a portable stadiometer, placed on a flat surface. The participant was instructed to remove any object from the head that interfered with the quantification, which remained with the back to the anthropometer, with legs and feet parallel and arms along the body. After aligning the back of the head, back straight, the mobile part of the stadiometer was moved to the highest point of the head.

For the calculation of the Body Mass Index (BMI), height was collected with a stadiometer and weight using a properly calibrated digital scale and the values were categorized according to the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO)[

14] , namely, low weight : <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: 18.5 – 24.99 kg/m2; overweight: 25 – 29.99 kg/m2; obesity grade I – 30-34.99 kg/m2; obesity grade II: 35 – 39.99 kg/m2; grade III obesity ≥ 40 kg/m2.

Blood pressure assessment was performed following the protocol of the Beira Baixa Blood Pressure Program (PPABB) program, using an automatic device to measure blood pressure levels. After the questionnaire and weight and height were removed, the patient remained seated for a few minutes before starting the first measurement. Participants kept comfortably seated, most of the time with the arm resting on a flat surface, straight posture, without talking and without making movements. The cuff was placed at heart level over the brachial artery, 2 – 3 cm above the cubital fossa. Additional assessments were made when the first two readings varied by more than 10 mmHg. Blood pressure values were classified according to the 2018 Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology [

15] .

The presence of diabetes was verified through the questionnaire and blood glucose assessment performed at the time of the survey. The evaluation was performed using a manual device with a FreeStyle blood glucose test strip. Before collecting the blood sample, the pricking finger was disinfected with cotton wool soaked in alcohol, using single-use disposable needles. The values were analyzed according to data from the protective association of diabetics in Portugal [

16] , considering a diabetic individual when he/she has a fasting blood glucose level >126mg/dl or 2 hours after a meal >200 mg/dl.

Cholesterol was assessed through questions addressed to participants about their knowledge of cholesterol levels, triglycerides and history of use of medication to reduce it.

3. Results

The study sample consists of 599 individuals, 100% black with a predominance of females 54.8%, and its distribution is made by the nine municipalities of the island of Santiago. It is distributed proportionally, with the municipality of Praia with the largest number of the sample 54.9%, followed by the municipality of Santa Catarina with 15%, Santa Cruz 8.2%, Tarrafal 5.7%, São Domingos 4.5%, Calheta São Miguel 4.3%, Ribeira Grande de Santiago 2.7%, São Salvador do Mundo 2.7% and São Lourenço dos Orgãos 2.2%.

The minimum age of the participants was 18 years and maximum 90 years, mean of 44 years, median 42, mode 26 and standard deviation ± 17.06 years. Most individuals have primary or secondary education. It was possible to perceive by the analysis of table 1 that the age group with the largest number of the sample is 18-27 years and that in all age groups, with the exception of the 18-27 years group, most individuals are female.

Table 1.

Distribution of subjects participating in the study by age group and sex.

Table 1.

Distribution of subjects participating in the study by age group and sex.

| Age Group (in years) |

% Total |

% Female sex |

%Male sex |

| |

| 18 a 27 |

21 |

46.8 |

53.2 |

| 28 a 37 |

20.4 |

53.3 |

46.7 |

| 38 a 47 |

19.5 |

52.1 |

47.9 |

| 48 a 57 |

14.5 |

50.6 |

49.4 |

| 58 a 67 |

14.2 |

65.9 |

34.1 |

| 68 a 77 |

6.7 |

67.5 |

32.5 |

| 78 a 87 |

3.3 |

70 |

30 |

| >88 |

0.3 |

100 |

0 |

| |

|

|

|

Table 2.

Classification of the Body Mass Index and Daily Habits of the individuals in the sample.

Table 2.

Classification of the Body Mass Index and Daily Habits of the individuals in the sample.

| Risk factores |

% Total |

% Female sex |

%Male sex |

| Weight in BMI (kg/m2) |

|

|

|

| <18.5 (Low Weight) |

9.3 |

46.4 |

53.6 |

| 18.5 - 24.99 (Normal Weight) |

48.1 |

46.2 |

53.8 |

| 25 - 29.99 (Overweight) |

27.2 |

58.3 |

41.4 |

| >30 (obesity) |

15.4 |

80.4 |

19.6 |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

65.1 |

60.5 |

39.5 |

| active smoker |

7.3 |

16 |

84 |

| Daily alcohol habit |

14.4 |

4.7 |

95.3 |

Table 2 shows that the majority of the study population (48.1%) had a normal BMI. Both overweight and obesity were more present in females. In the same way, we found that the majority of sedentary people are female (60.5%), on the other hand, the smoking and alcoholic habits were more prevalent in males.

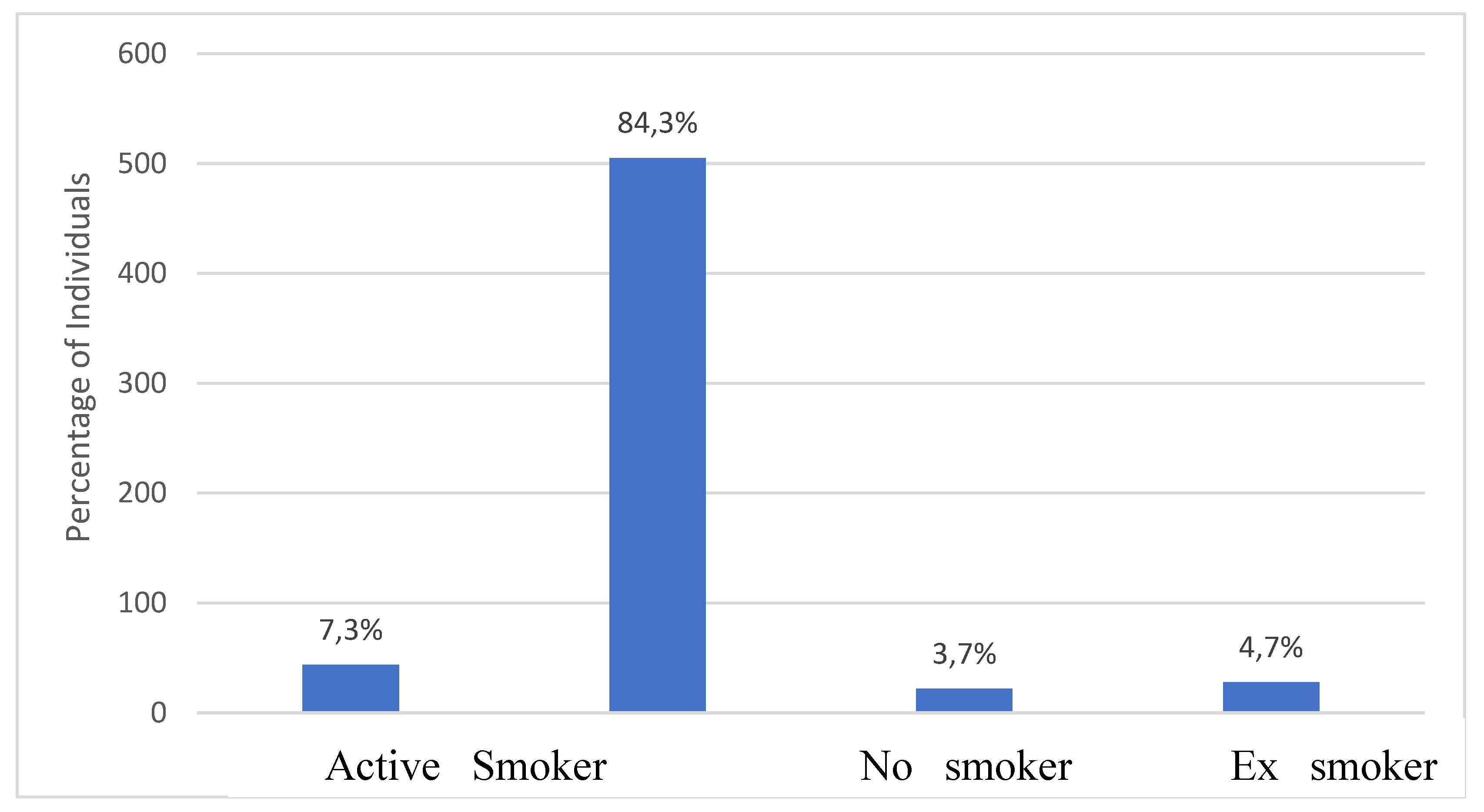

Figure 1.

Analysis of the risk factor “Smoking”.

Figure 1.

Analysis of the risk factor “Smoking”.

Considering the risk factor of smoking, 84.3% of respondents did not smoke, 7.3% were active smokers (84% were male), 3.7% of former smokers (90.9% were male) and 4.7% used drugs. The average year of cigarette consumption reported by smokers was 16.8 years and the average number of daily cigarettes consumed by active smokers was +/- 6 units. Only 2 individuals consumed 1 pack of cigarettes per day. Smoking was more prevalent in the 28-47 age group (53.48%).

Regarding the consumption of alcoholic beverages, 14.4% reported having a daily habit of consumption (95.3% males), 37.1% had the infrequent habit and only on weekends/festivities (53.1% males). The average daily consumption was 3.7 glasses, 92.7% had the habit of consumption inside and outside of meals.

Table 3.

Lipid Profile of the individuals in the sample.

Table 3.

Lipid Profile of the individuals in the sample.

| Risk factores |

% Total |

% Female sex |

%Male sex |

| Hypercholesterolemia |

8.3 |

80 |

20 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia |

1.3 |

62.5 |

37.5 |

Regarding the lipid profile measured through the questionnaire, hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia were all more prevalent in females and in the 58-67 age group.

Presence of Cardiovascularbrain Diseases

As for the prevalence of cardiac pathologies in the respondents, it was found that 6.5% had diagnosed cardiac pathologies, 79% said they had never had any heart disease and 14.5% said they were not aware of the presence of heart disease. When we relate this variable to gender, we can see that 79.5% of individuals with heart disease are female. The cardiac pathology most mentioned by the respondents were palpitations, representing 59% of the total responses, followed by 10% who did not know the name of the diagnosed cardiac pathology, 10% murmur, 5% tiredness, 5% arrhythmia, 3% tachycardia, 3% pain thoracic, 3% bradycardia.

Of the respondents, 19.9% mentioned having close family members with heart disease. Of these 116 individuals with direct family members with cardiac pathologies, 65.5% did not know the name of the pathology of their family members and the rest reported that their family members had the following cardiac pathologies: 6.9% arrhythmia, 6% murmur, 6 % thrombosis, 4.3% heart attack, 4.3% valvular pathology, 1.7% dilated heart disease and 0.9% palpitations, 0.9% Heart failure, 0.9% Infarction, 0.9% aortic pathology, 0, 9% Aortic stenosis, 0.9% heart transplantation.

Of the cerebrovascular diseases, 2.7% reported having had a stroke (68.8% female) and 0.1% transient ischemic attack - TIA (1 male). Of the respondents, 0.5% reported having had ADE, all female. These female subjects stated that before the occurrence of AMI they already had risk factors such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes.

We analyzed the periodic habit of evaluating blood pressure and it was verified that 23.5% of the participants have the regular habit of evaluating blood pressure, with this habit being more present in females 69.5% than in males.

Assessment of Blood Pressure and Glycemia

To determine the values of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, the average of the three assessments performed according to the protocol was taken. The systolic pressure evaluated in the respondents ranged between 76 mmHg and 211.47 mmHg with an average of 128.47 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure ranged between 51.67 mmHg and 150 mmHg with an average of 82.75 mmHg.

It was found that 32.6% of the participating population had values suggestive of arterial hypertension, being 53.8% female and 46.2% male. Of the 195 hypertensive patients identified, 34.6% had grade I hypertension, 26.2% grade II hypertension, 14.1% grade III hypertension and 25.1% isolated systolic hypertension.

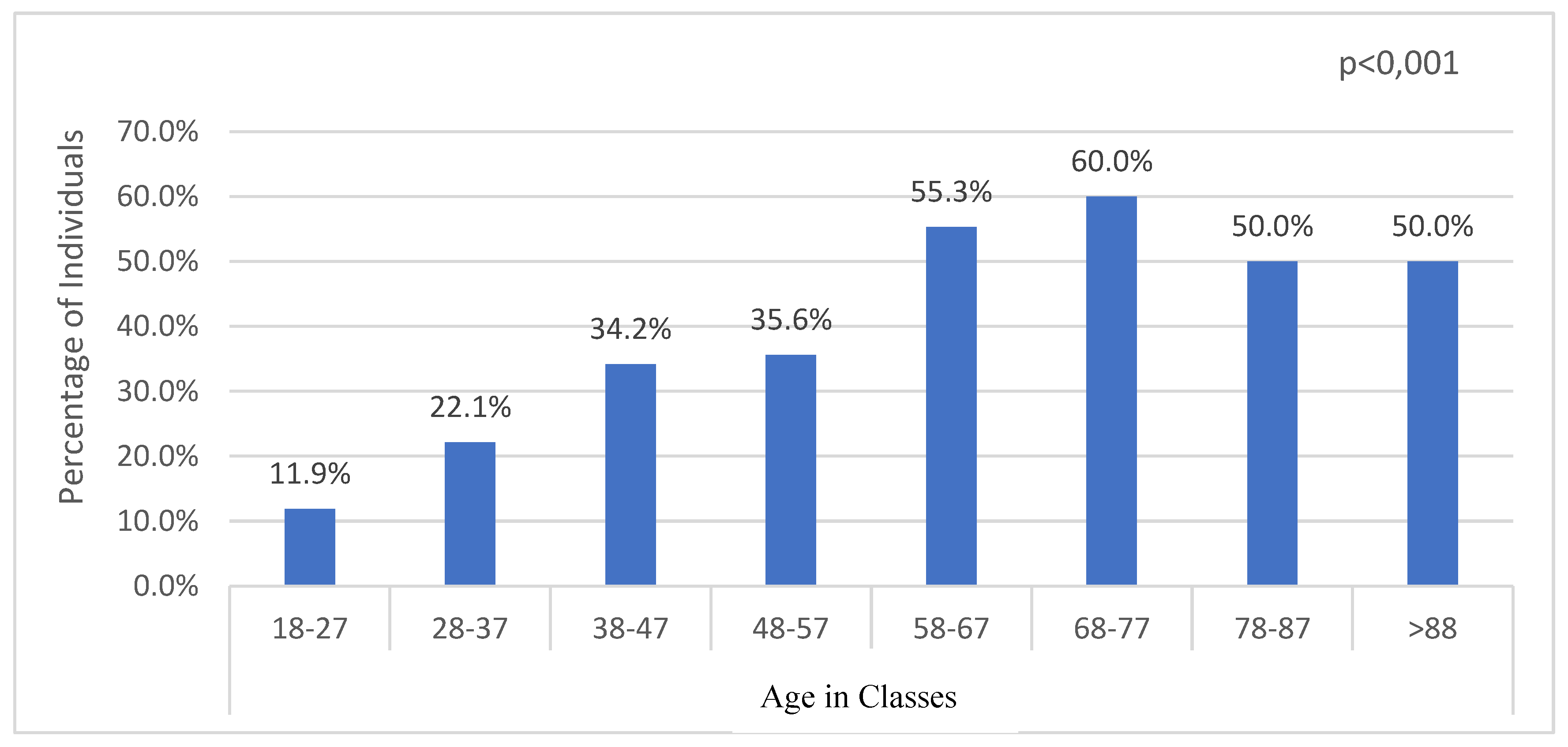

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of arterial hypertension by age group.

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of arterial hypertension by age group.

Of these hypertensive patients, there is a higher prevalence in the age group of 68-77 years, followed by 78-87 years and > 88 years, according to the distribution of our sample by age group. It can be seen that in the age group of 18-27 years there is a lower prevalence of hypertension, with a tendency to gradually increase with age, with a slight stabilization from the age group of 78-87 years (

Figure 2).

Table 4.

Relationship between Arterial Hypertension and Risk Factors.

Table 4.

Relationship between Arterial Hypertension and Risk Factors.

| Risk factors |

P- value |

| Sex |

0,755 |

| Age Group |

< 0.001 |

| Body Mass Index |

0.781 |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

0.268 |

| Alcoholism |

0.234 |

| smoking |

0.307 |

| Diabetes |

0.041 |

Hypertension has no relationship with sex, BMI, physical inactivity, alcoholism and smoking, although there is a statistically significant relationship with diabetes and age group.

As for the level of blood glucose measured, it was classified according to data from the protective association of diabetics in Portugal. The blood glucose value ranged from 32 mg/dl to 389 mg/dl, with an average of 104.95 mg/dl. 89.8% were performed after the meal. We found that 6.2% of the participants had values corresponding to hypoglycemia, 81.6% had normal blood glucose values, 7.7% had values indicative of pre-diabetics and 4.5% had values corresponding to diabetes. Of the 27 individuals who had a blood glucose level considered diabetes, 56.5% were female and the most prevalent age group was 58-67 years (30.4%) and 60.9% were sedentary.

Table 5.

Relationship between Diabetes and Risk Factors.

Table 5.

Relationship between Diabetes and Risk Factors.

| Risk factors |

P- value |

| Sex |

0.460 |

| Obesity |

0.418 |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

0.664 |

| Age Group (58-67 years) |

0.002 |

| Level of Education (Basic Education) |

0.536 |

| Alcoholism |

0.732 |

| smoking |

0.380 |

There was no statistically significant relationship between diabetes and the risk factors of sex, obesity and physical inactivity. Diabetes showed a significant relationship with age group (58-67 years) p=0.002. It was possible to notice that 60.9% of individuals with diabetes have basic literary education, but this did not show any significant relationship, p=0.536.

It was also found that both diabetes and hypertension did not show any significant relationship with alcoholism and smoking.

Taking into account the risk factors and the prevalence found within each municipality through table 6, it is possible to observe that obesity is more prevalent in the municipality of Santa Cruz; sedentary lifestyle, smoking, hypertension and diabetes are present in higher percentages in Ribeira Grande de Santiago; hypercholesterolemia in the municipality of São Domingos and hypertriglyceridemia in São Salvador do Mundo.

Table 6.

Distribution of risk factors by municipalities.

Table 6.

Distribution of risk factors by municipalities.

| |

Municipalities |

| P |

Sta.C |

S.C |

T. |

S.D |

C.S.M |

S.SM |

R.G.S |

S.L.O |

| Obesity % |

17,6 |

10 |

18,4 |

8,8 |

14,8 |

23,1 |

6,2 |

6,2 |

8,3 |

| Sedentary lifestyle % |

65,3 |

58,9 |

77,6 |

67,6 |

40,7 |

76,9 |

50 |

87,5 |

66,7 |

| Alcoholism % |

7,9 |

11,1 |

30,6 |

50 |

14,8 |

11,5 |

18,8 |

31,2 |

25 |

| Smoking % |

8,8 |

7,8 |

2 |

29 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

25 |

16,7 |

| Hypertension % |

34 |

27,8 |

24,5 |

29,4 |

25,9 |

34,6 |

43,8 |

50 |

41,7 |

| Diabetes % |

4,3 |

5,6 |

0 |

2,9 |

3,7 |

3,8 |

0 |

6,2 |

0 |

| Hypercholesterolemia% |

9,4 |

10 |

4,1 |

2,9 |

11,1 |

3,8 |

6,2 |

6,2 |

8,3 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia% |

0.6 |

3,3 |

0 |

0 |

3,7 |

3,8 |

6,2 |

0 |

0 |

We can conclude that, in general, the municipality of Ribeira Grande de Santiago was the locality where more risk factors (sedentary lifestyle, smoking, hypertension and diabetes) were present in the respondents in the locality.

4. Discussion

Cape Verde is a country where a large part of the population leads an unhealthy lifestyle, low consumption of vegetables, little practice of exercise and a high consumption of tobacco and alcoholic beverages, a diet rich in sodium and fat, factors that increases the development of risk factors [

21] .Santiago Island is the largest island, it has a population diversity and different lifestyles, with variation between urban, rural and port areas, this allows us through the study to have a perception of the health status of NCDs, particularly of cerebrocardiovascular etiology. According to statistics on living conditions in Cape Verde 2015-2016, diseases of the circulatory system continue to be the main cause of mortality, with a rate of 161.2 per hundred thousand inhabitants, with females having a higher rate [

17] .

In order to study risk factors on Santiago Island, a sample consisting of 599 individuals was determined, which was predominantly made up of women (54.8%), which was related to a similar study carried out in Cape Verde “Study of cardiovascular prevalence in Cape Verde - Ilha do Maio” [

18] where there was also a higher prevalence of females (55.4%), a prevalent age of 19-29 and 30-40 years and the predominant level of education, which was basic education, given these are in line with the results found on the island of Santiago.

Food is a determining and fundamental factor for the maintenance of health and well-being, it is already very clear that food has a direct relationship with the development of many pathologies, namely cardiovascular diseases. The WHO recommends the daily consumption of at least 5 or more pieces of fruits and or vegetables, being below this average is considered a risk factor for the development of cardiovascular diseases. According to the National Survey on Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases (IDNT II) - STEPS 2020 described the daily habits of Cape Verdeans: the average number of fruit was 3.5 pieces per day, 8.5% of the adult population consumes salt or salty sauce before or during meals, 10.2% of the adult population often consume processed and high-salt foods, 15.5% always or often consume fatty foods (16.8% men), 30.6% always or frequently consume sugary foods and/or drinks (30.9% in men)(21). It can be seen from these data that in Cape Verde there is a part of the population with little care in terms of food and that can be explained by sociocultural, economic, demographic and lifestyle determinants. These habits will consequently reflect overweight and obesity, which constitute a strong factor for the development of cardiovascular events.

Obesity is a global epidemiology that increasingly becomes a threat to public health in both sexes, in different age groups and races, being an important risk factor for the development of cardiovascular events [

19,

20]. The IDNT II – STEPS Report 2020 [

21] highlighted that 44.2% of adults are overweight and 14.3% are obese. We considered all BMI≥25Kg/m2 as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and it was found that 27.2% of individuals are overweight and 15.4% are obese, with a total BMI ≥25Kg/m2 of 42.6%, in relation to these data, we can see that The percentage of obese between the two studies is very similar, however, for overweight and total weight above 25Kg/m2, it is higher in the national study, which includes a larger sample number and population diversity in different islands, which may justify the difference.

A similar result to ours was found in the study “The prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus and obesity in the adult population of Guinea-Bissau: a pilot study”[

22] which found an obesity rate of 43.7% and the BMI classification criterion was the same between the two studies. A superior result can be seen in the study “Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Portugal” [

23] in which the estimated excess weight was 38.9% and the prevalence of obesity was 28.7%, a higher prevalence than ours may be. be explained by the difference in the study, given that this was a cross-sectional population-based study that was representative at regional and national levels, by the larger total sample size of 12,289 individuals, age range from 25-74 years and by race.

Daily habits play an important role in the development of CVD, smoking, alcoholism and physical activity are modifiable risk factors with a great impact on the health of each individual. According to the STEPS 2020 report (21) "Alcoholism in Cape Verde is not only one of the main public health problems, but also a conditioning factor for the country's development, causing great concerns for families and authorities".

The studies, “Alcohol and tobacco consumption: risk factor for cardiovascular disease in the elderly population of southern Brazil” [

24] , “Association between Alcoholism and Subsequent Systemic Arterial Hypertension: A Systematized Review” [

25] stated that alcohol and tobacco cause negative effects on health, with emphasis on an increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases. Alcohol consumption was reported by 14% of the sample of our study in which the age group that presented a higher percentage of the smoking and alcoholism factor was 28-47 years old. The IDNT II- STEPS 2020 report [

21] showed a higher percentage than that found in the results of the island of Santiago, with the adult population that consumed alcoholic beverages (last 30 days in relation to the survey) is 45.0% (62.3 % male) and alcoholism for both sexes the percentage was higher in the age group from 30 to 44 years. The survey carried out in Cape Verde by the Ministry of Health in 2016 on risk factors showed that 6.3% of men and 2.4% of women have a high alcohol consumption pattern [

2] . Both the IDNT II and the survey carried out by the Ministry of Health are of a national nature and with a larger sample, the prevalence of risk factors is constantly changing, which may justify the increase in alcohol consumption by the population in 2016 to 2021. It should be noted that alcohol consumption in Cape Verde has a high incidence rate in the young population, according to the study “Alcohol consumption in students of the 12th year of the high school of coculi in the municipality of Ribeira Grande de Santo antão: interventions of nursing” reported a prevalence of consumption very close to 50% and of these an expressive number consumes at risk, several days a week representing 12.8% of the sample, also showing the existence of possible cases of dependence [

26] . Our alcoholism rate was lower than that of the IDNT 2020, because the study is only on Santiago Island, the lifestyle differs a lot between the Islands.

Smoking is a modifiable risk factor that causes damage to the respiratory system and contributes to the accumulation of atheromatous plaques in the arteries that consequently lead to stroke and AMI. Studies such as “Smoking and Cardiovascular Diseases” [

27] and “Smoking and its relationship with venous thrombosis”[

28] demonstrate the impact of smoking on the cardiovascular system. In our research work, we found that 7.3% of the individuals surveyed are active smokers, the majority (84%) are male, and in the age group of 28-47 years. The smoking factor showed a statistically very significant relationship with males, age group When we related our results with those of the STEPS 2020 report [

21] we noticed that the results we found are higher, in the STEPS 2020 report only 4.9% of the adult population smoke daily, being 53.5% men. Regarding the age group, the statistical report found a higher prevalence in the age group from 60 to 69 years. We can verify that there was a decrease in tobacco consumption comparing with the 2012 data from Panapress Cape Verde, which had a prevalence rate in adult smokers of 17.4% [

29] . The results we found show lower percentages and in a younger age group.

Regular physical exercise improves the lipid profile, stimulates the production of vasodilating substances and improves endothelial function. It is very clear that exercise is essential for a healthy life and constitutes a means of preventing cardiovascular pathologies, it reduces the level of cholesterol, type II diabetes, triglycerides, hypertension, obesity and stress, among other benefits [

30] . WHO data show that one in four adults and four in five adolescents are not active, and physical activity contributes to maintaining good physical condition and, consequently, to reducing risk factors [

31]. The benefit of physical activity has been demonstrated in the studies “Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Risk Modulation” [

32] and “Level of physical activity in elderly participants in a cardiovascular disease prevention program” [

33] .

Of the individuals studied, 34.1% of the population has an exercise routine, with a greater predominance in males and an average of +/- 4 times a week with an average duration of 59 min and 46 sec. We found that 65.1% of the population is sedentary (60.5% female). This data corroborates the data from the IDNT II 2020[

21] where they found that the population practices an average of 144.6 minutes of physical activity per day, and that men lead a more active life than women. The study “Sedentary lifestyle: Prevalence and Association with Systemic Arterial Hypertension in Salvador”[

44] showed a sedentary lifestyle rate 55.3% lower than that found by us, which may be related to the lifestyle of the country where the investigation was carried out.

Diabetes Mellitus is a metabolic syndrome responsible for pathophysiological changes giving rise to hyperglycemia. Type II diabetes is the most common (more than 85%) triggered by insulin resistance, which is greatly influenced by the previously mentioned modifiable factors [

34] . Hyperglycemia leads to the triggering of pathologies of the circulatory system, namely stroke, AMI and peripheral vascular disease. Data from 2017 show a global prevalence of diabetes of 425 million, with a tendency to increase to 629 million by 2045 [

35] .

The IDNT II 2020 report [

21] points out that 3.9% of the adult population of Cape Verde was diagnosed with diabetes (higher p), with a predominance in females, with 16.6% of diabetics being in the age group of 60-69 years. Data by us presents a slightly higher value than that presented by the statistical report, we found 4.5% individuals with diabetes, 56.5% are female and the most prevalent age group was 58-67 years. The study also carried out on the Island of Santiago “Self-reported prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus Type 1 and 2 on the Island of Santiago – Cape Verde: a cross-sectional study” (2020) [

36] , refers to a prevalence of 3.3% of diabetes, being 69.9% women. The data from this study show a lower value than the values found by us, this may be due to the number of individuals studied in the two studies and the different collection method carried out in the health centers of the Island of Santiago in the year 2018/2019. Despite the difference in the percentages found, the female gender prevails in both studies. feminine.

Through the questionnaire that we applied, we realized that most of the surveyed individuals were not aware of their cholesterol and triglycerides level, most individuals reported never having evaluated their cholesterol and triglycerides level. We found that 8.3% of the individuals reported having hypercholesterolemia and 1.3% high triglycerides, both with a higher percentage in females and more present in the age group of 58-67 years. Of the individuals with hypercholesterolemia, 20% reported that they did not undergo any treatment or control. Higher data were found in the research “Prevalence of dyslipidemias and food consumption: a population-based study” in which there was a high prevalence of dyslipidemias in the population (64.25%) [

37] , which proved to be a much higher data than for we found. We believe that one of the main reasons for this difference is the fact that this data was collected through a questionnaire, which may be a limitation of the study. We suggest that blood analysis collection studies be carried out to assess cholesterol and triglyceride values for the real assessment of the prevalence of these risk markers.

Arterial hypertension is the modifiable cerebrocardiovascular risk factor that represents a high global mortality rate and the cause of many morbidities and disabilities. It is estimated that approximately 1.13 billion people are affected by hypertension, causing approximately 45% of deaths from heart disease and 51% of deaths from stroke, resulting in more than 8 million deaths per year and 92 million years. of life due to disability [

38] . Most of the time, the cause of arterial hypertension is unknown, but factors such as sedentary lifestyle, obesity, inadequate diet, alcohol, tobacco, diabetes and stress are very present at the origin[

39,

40].

Some studies such as the one by Morales [

41] show a reduction in morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular events with the treatment of arterial hypertension. According to the manual “Protocol Approach to Vascular Accident (2021)” [

42] it is stated that 30.8% of Cape Verdeans have arterial hypertension (HTA), and 70.2% are without frequent medication for hypertension. The questionnaire allows us to know that in Cape Verde the habit of assessing blood pressure is still not very prevalent, only 23.5% of respondents had the regular habit of measuring blood pressure, with 69.5% more frequent among females.

Through the average of the three blood pressure values that we evaluated, we noticed that 32.6% of the population participating in the study had values suggestive of arterial hypertension, 53.8% of which were female, with a higher predominance of Grade I hypertension (34.4%). These data are in agreement with the study by Morales [

41] . The age group most affected is 68-77 years, followed by 78-87 years and > 88 years. The study carried out in Guinea-Bissau “Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus in the adult population of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau exploratory study” [

43] , used a methodology very similar to that of our study and showed a prevalence of hypertension of 33.2%, a percentage that is very similar to the results found for the island of Santiago.

We can conclude that, in general, the municipality of Ribeira Grande de Santiago was the locality where more risk factors (sedentary lifestyle, smoking, hypertension and diabetes) were present in the respondents in the locality. There are no studies and data available on risk factors and habits/lifestyle in the Municipalities of Ribeira Grande de Santiago – Santiago Island for us to discuss this finding, but we believe that there is an influence of lifestyle and lifestyle habits since the municipality belongs to a port location where the population seems to have a habit of consuming a lot of salt, fried foods and consumption of alcoholic beverages.

Our research was based on a randomly selected representative sample covering different age groups and social classes, which leads us to have a comprehensive knowledge about the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. Through the results, it can be noted that female individuals had more cerebrovascular risk factors and in more advanced age groups, with the exception of the factor smoking and alcoholism, which was more prevalent in males. These data are in line with the Ministry of Health and Social Security-statistical data from the 2017-2018 survey, which shows that females have a higher incidence of risk factors and a higher number of CVD mortality [

2] .