1. Introduction

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) clinical guidelines, manual titration of positive airway pressure during attended polysomnography is the current standard for the selection of the optimal patient therapeutic pressure for patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) are the two forms of PAP that are manually titrated during a PSG to determine the optimal amount of pressure for subsequent nightly usage. In pursuing effective and well-tolerated airway pressure therapy, patients often undergo PAP titration procedure for diagnostic measurements (1). This essential step aims to determine the appropriate air pressure required to maintain an open airway during sleep. However, the current strategies for PAP titration have certain disadvantages. Manual adjustments of parameters, e.g. pressure and oxygen fraction can be challenging due to complex interactions with other NIV parameters like tidal volume and PEEP (Positive End-Expiratory Pressure) (2).

Furthermore, the accuracy of obtained SpO2 data may vary, potentially introducing errors in the titration process (3). Some individuals may necessitate long-term oxygen therapy, even when using PAP devices (4,5). A common co-occurring condition in OSA is chronic hypercapnia, which may further necessitate oxygen supplementation. Chronic hypercapnia can have adverse effects on respiratory and cardiovascular systems, making its management a crucial aspect of OSA treatment. Additional oxygen supplementation in positive airway pressure treatment increases blood oxygen saturation, but it may also lead to bradypnea in patients with chronic hypercapnia, exacerbating their condition (6). This emphasizes the importance of precise oxygen titration techniques, especially when addressing chronic hypercapnia co-occurring with OSA.

Recognizing the disadvantages of manual adjustments, the study tackles the development of a Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) for time efficiency in the titration of airway pressure and additional oxygen supply. Automation and expert-based control systems are crucial components, offering the potential for enhanced treatment adaptability and effectiveness while minimizing patient discomfort and time-consuming healthcare provider burden. The application of Markov Decision Processes (MDP) as a CDSS presents a significant yet intricate challenge, introducing innovative possibilities along with complex issues. MDPs provide a framework for modeling sequential decision-making under uncertainty, allowing decision-makers to maximize the probability of reaching desired states (7)

To address limitations of manual titration and enhance the precision of OSA treatment, the integration of Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS), based on Markov Decision Process, for automated PAP and oxygen titration has been explored in this study to describe the potential markers for the CPAP transition to BiPAP.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted and marketed in conformity with all regulatory enactments regulating data protection in the Republic of Latvia, including the Law on the Processing of Personal Data (protocol number E1.1.1.1/21/A/082, clinicaltrials.gov: NCT06090149). The patient population consisted of adults with OSA-induced hypoxemia who used additional oxygen supply and CPAP/BiPAP therapy. Patients included in the study are initially identified by reviewing medical records at Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital (PSCUH) for hospital patient medical cards. The study’s inclusion criteria encompassed individuals aged 18 and above who had OSA with specified criteria such as AHI values, documented symptoms, and associated health issues, as well as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) with documented hypoxemia without additional oxygen support. Additionally, conditions involving the overlap between COPD and OSA or between pulmonary hypertension and obstructive sleep apnoea were considered. On the other hand, the exclusion criteria involved individuals with COPD and OSA lacking documented hypoxemia, those under 18 years old, those requiring permanent replacement therapy for another organ, individuals contraindicated in non-invasive pulmonary ventilation, those refusing study participation, those with cognitive impairment hindering research completion, individuals with claustrophobia, pregnant individuals, and those with severe heart failure or recent cardiovascular events according to New York Heart Association functional class III–IV within the month preceding study inclusion.

During the study, patients were subjected to PAP titration while receiving supplemental oxygen through an oxygen concentrator. The research took place over one night, spanning from 22:00 to 8:00, covering a 10-hour duration. A sleep technician meticulously observed a variety of vital signs and physiological parameters including monitoring respiratory flow, thoracic and abdominal movements, body position, respiratory rate (RR), heart rate (HR), blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), and levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) during transcutaneous measurements. The study also involved the collection of significant data, including the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), and sleep architecture. Throughout the night, the sleep technician observed the patient’s condition, ensuring precise monitoring of all relevant parameters. This included the vital task of fine-tuning CPAP/BiLEVEL settings, adapting unit pressures, and controlling oxygen delivery as needed. These adjustments were carefully guided by the patient’s thoracic and abdominal movements, airflow patterns, blood SpO2 levels, and pCO2 concentrations. To facilitate this monitoring and care, patients were placed in a dedicated room equipped with monitoring and treatment equipment. The physician assistant conducted their observations and managed patient care from a separate room, utilizing remote control to make necessary adjustments.

PAP titration and data acquisition protocol: The CPAP pressure underwent a gradual adjustment to alleviate or eliminate apnea episodes. In cases where patients experienced tolerance issues, the PEEP level was lowered or switched to a BiLevel treatment. Supplementary oxygen was introduced based on the patient’s SpO2 levels, with a target of maintaining SpO2 levels of at least 89%. Continuous monitoring of pCO2 levels was carried out, and if there was a 5-unit increase in pCO2 or if SpO2 levels exceeded 95%, the oxygen flow was tapered down. The data acquisition process involved using the Lowenstein medical BiLevel Prisma 25ST device, which offered various modes such as CPAP, APAP, and BiLEVEL. This device also facilitated online monitoring of pressure, tidal volume, and mask leaks. Additionally, pCO2 levels were monitored using the Sentec device, which seamlessly integrated with the Lowenstein medical diagnostics report, and all the parameters were displayed in real-time on the screen. To complement the data collection, supplemental oxygen was administered through the Devilbiss 525 KS oxygen concentrator. When necessary, a physician’s assistant manually conducted additional data acquisition, particularly while making adjustments to the PAP settings and when adding or removing oxygen from the treatment.

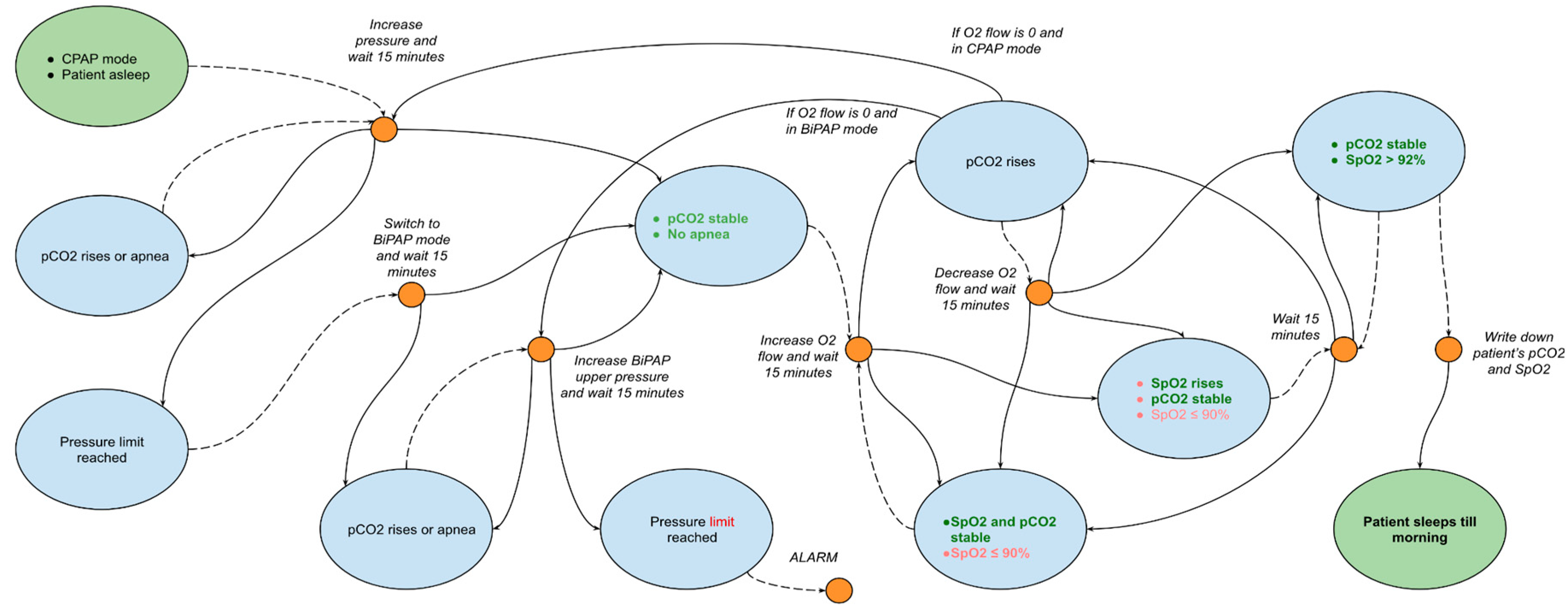

Diagnostic prediction task. The therapeutic approach for sleep disorder management is delineated into three distinct phases, underpinned by Markov Decision Processes and expert medical insights (

Figure 1). Initially, patients underwent polysomnographic monitoring (SpO

2, pCO

2) and CPAP administration during sleep. The model’s initial state involves monitoring until apnea subsides. Transitioning to the second phase involves titrating CPAP pressure based on pCO

2 dynamics, potentially escalating to BiPAP, if CPAP tolerance is exceeded. This phase is characterized by adjusting pressures in response to pCO

2 changes, with expert input crucial for defining transitional probabilities.

The final phase focuses on oxygen flow modulation, dependent on SpO2 and pCO2 readings, aiming to achieve SpO2 above 90%. This represents the MDP’s terminal state. Throughout, the model relies heavily on medical expertise to define states and transitions, particularly in optimizing CPAP/BiPAP settings and interpreting respiratory parameters.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient cohort description.

The final patient cohort comprised 14 OSA patients with sleep-disordered breathing evaluated in the Sleep Clinics between November 2022 and August 2023 (Supplementary 1, Annex 1). The cohort was selected based on PSG or strong clinical evidence of significant improvement in OSA following a single-site operative intervention. The average age was 63 years (range 50-79 years, standard deviation [SD] 8 years). 27% of the study group were females (N=4). The average body mass index (BMI) was 41 kg m−2 (range 23-55 kg m−2, SD 9 kg m−2). The average AHI of the PSGs (one patient contributed two separate PSGs at clinically discrete time points) included in our training and testing datasets was 61.8 events per hour (range 21.4-109.2 hr, SD 29.1 hr). The average initial blood oxygen saturation was 79.7% (range 67.1-90%, SD 7.72%). The average initial pCO2 was 53 mmHg (range 39-63 mmHg, SD 8 mmHg). In total 2 patients were normocapnic (<45 mmHg), while 12 patients were hypercapnic (9 patients had initial pCO2 level below 55 mmHg, while 4 had above 55 mmHg).

3.2. Results of the PAP and oxygen titration.

The results of PAP and oxygen titration are summarized in the

Table 1 and revealed statistically significant improvements in SpO

2.

The average blood oxygen saturation increased to 89.1 % (range 79.2-98.6%, SD 5.0%), reflecting a substantial enhancement in oxygen levels during sleep. The average delta values of SpO2 were 9.4 % (range 0.4-21.9 %, SD 6.25%). The median delta values of SpO2 were 8.1%, IQR 8.5%.

Additionally, the AHI index demonstrated a statistically significant reduction, with an average decrease to 18.0 events per hour (range 1.3-46.8 events/hr, SD 13.9), highlighting a substantial amelioration in sleep-disordered breathing. The average Delta values of AHI were 48.0 (range -18.6-89.9 events/hr, SD 33.1), while the median were 53.5 events/hr, IQR 46.45 events/hr. These findings underscore the positive impact of the single-site operative intervention on key physiological parameters in our patient cohort. T-test shows p<0.0001.

In case of pCO2 levels there were no statistically significant changes in pCO2 before and after the PAP titration (average 53 mmHg, range 43-59 mmHg, SD 5 mmHg). The average delta values of pCO2 were 1 mmHg (range 6-9 mmHg, SD 5 mmHg).

3.3. Pearson Correlation - pressure/pCO2/SpO2. Indications to proceed to BiPAP therapy.

Table 2 examined the Pearson correlation coefficients for pCO

2 and SpO

2 in relation to CPAP and IPAP pressure values. Normocapnic patients (N=2) with SpO

2 >88% at the beginning of the PAP titration remained normocapnic within the treatment. Notably, 50% of patients whose initial pCO

2 was below 55 mmHg (N=5) during CPAP intervention exhibited a positive Pearson correlation coefficient for pCO

2. Conversely, those with an initial pCO

2 above 55 mmHg (N=4) did not correlate strongly with pCO

2. When CPAP therapy was transitioned to BiPAP therapy (N=7) there was a strongly correlated decrease in pCO

2 corresponding to the increase in IPAP pressure in all patients.

A comparative analysis between CPAP and BiPAP therapies revealed a higher amount of significantly stronger correlations in the increase of SpO2 with BiPAP therapy. Within the BiPAP titration, the increase of oxygenation was strongly correlated in 57% of patients (N=4), while a strong positive correlation on the CPAP treatment was observed in only 7% of patients (N=1). A strong negative correlation was observed in one patient who received CPAP therapy. Notably, for those patients whose pCO2>55 mmHg, there was no strong correlation in an increase of SpO2 within CPAP treatment while BiPAP therapy showed a strong correlation in 50% of cases (N=2).

3.4. Markov decision process.

In order to describe the Markov decision process, two patients were selected that had more than one hour of intervention sleep and had additional supplementary oxygen therapy. Supplementary material 1, Annex 2, holds screenshots from polysomnography application, where all parameters can be overseen. Annex 2a shows MDP’s first step, where CPAP pressure is raised until apnea episodes disappear (12 mmH2O). Apnea episodes are shown as pink rectangles. Next decision step is where pCO2 is stable and oxygen is added. Annex 2b shows that pCO2 stabilizes at 60 hmmHg and even decreases to 55 mmHg and then 1 L/min of oxygen is added, promoting an increase of SpO2. After a while the next MDP step can be seen (Annex 2c) where pCO2 is rising from 55 to 60 mmHg after an increase of oxygen supplementation to 2 L/min of oxygen supplementation. After decreasing oxygen to 1 L/min, pCO2 drop to 53. At the same time SpO2 were rising during O2 of 2 L/min reaching 96% and after switching to 1 L/min, drops to 92%, which is acceptable. After a while the patient woke up at 5 am and was mostly stabilized, nevertheless pCO2 could be better. As a result MDP shows realistic behaviour on the patients that were stable in the night with minimal amount of apnea and good toleration to high CPAP pressure.

4. DISCUSSION

The average overall increase in SpO2 to 89.1% reflects a substantial improvement, with noteworthy average delta values of SpO2 of 9.4%. The consistency of this improvement is further emphasized by the narrow standard deviation (SD) of 5.0%, suggesting a reliable and predictable response to manual PAP therapy across the patient cohort. The results however show the stronger correlation in oxygen support on the higher IPAP values, while the increase of the CPAP pressure didn’t strongly correlate with the increase. The main explanation might be the impact of the higher CPAP pressure on the exhale phase as well as the impact of the apnea events that may impact the fluctuation (8).

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines for conducting manual PAP therapy, BiPAP device may be used when a patient demonstrates difficulty acclimating to high airway pressure during the expiration phase of breathing or requires ventilatory support (1). The indications for transitioning to BiPAP therapy include patient intolerance to a CPAP therapy, persistent symptoms like excessive daytime sleepiness or snoring despite CPAP usage, and the observation of residual obstructive events at a CPAP pressure of ≥15 cm H2O. When evaluating suspected etiologies for these issues, if retitration with the same modality proves unsuccessful, the AASM recommends considering bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) therapy, particularly in the spontaneous mode. However, it is essential to note that the decision to switch to BiPAP is predominantly influenced by apnea events, with pCO2 and SpO2 monitoring playing a secondary role. It is worth mentioning that patients with hypoxia on CPAP therapy may require additional oxygen therapy, thus the speculation regarding the initiation of the O2 still persists. For instance, the administration of supplemental oxygen may exacerbate carbon dioxide retention, particularly in cases of type 2 respiratory failure. Notably, elevated oxygen concentrations may lead to a reduction in the respiratory drive, subsequently diminishing the ventilatory response. This diminished drive can impede the efficient elimination of CO2, potentially exacerbating hypercapnia (6).

It is crucial to observe the subgroup of patients whose initial pCO2 levels were below 55 mmHg during CPAP intervention. Among this cohort (N=5), a positive Pearson correlation coefficient for pCO2 was evident. This implies that, for a subset of patients with pCO2<55 mmHg levels, there was a discernible positive association between pCO2 and CPAP pressure values. Such a relationship may be also indicative of a physiological response to higher positive airway pressure, possibly implicating a greater challenge in exhaling effectively under these conditions. Conversely, patients with an initial pCO2 above 55 mmHg (N=4) did not exhibit a strong correlation between pCO2 and CPAP pressure values. This lack of positive and negative correlation suggests that for individuals with higher baseline pCO2 levels, the impact of CPAP pressure on pCO2 dynamics may be less pronounced. It is plausible that these patients have a different respiratory response or compensatory mechanisms that mitigate the influence of positive airway pressure on pCO2 levels. Transitioning from CPAP therapy to bilevel positive airway pressure therapy revealed a consistent and strongly correlated decrease in pCO2 as IPAP pressure increased across all patients (N=7). This finding implies that as the inspiratory positive airway pressure intensified, there was a corresponding reduction in pCO2 levels. BPAP allows the sleep technologist to separately adjust inspiratory and/or expiratory pressures during the polysomnogram to maintain the patency of the airway and provide ventilatory support. According to AASM guidelines when transitioning from continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to BiPAP, the minimum starting expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) should be set at 4 cm H2O or the CPAP level at which obstructive apneas were eliminated. An optimal minimum inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP)-EPAP differential is 4 cmH2O and an optimal maximum IPAP-EPAP differential is 10 cmH2O 2 (1). This inverse relationship between IPAP pressure and pCO2 suggests that, in the context of BiPAP therapy, higher inspiratory pressures facilitate a more efficient removal of carbon dioxide (9,10).

The statistically significant improvements in SpO2 and AHI following PAP and oxygen titration underscore the effectiveness of the manual PAP therapy in enhancing blood oxygen saturation during sleep. The reduction in the Apnea-Hypopnea Index from an average of 61.8 events per hour before titration to 18.0 events per hour after titration demonstrates a statistically significant manual PAP titration efficiency. Similar results of the manual titration were obtained in other studies (11). However it is time consuming to manually define the pressure support and the decision to switch the therapy from CPAP to BiPAP (12). Adjusting PAP parameters manually during the night presents several challenges, including the overload of sleep technologists. Moreover, this manual approach may increase the risk of human error in documentation and decision-making (13). The differences between automatic PAP titration and manual titration may come from how parameters such as apnea, hypopnea, and snoring are defined, as well as the use of different recording methods (2).

Several previous publications have raised the clinical problem of poor adherence of CPAP in OSA and telemedicine could be one of the solutions (14).

Within this study we have also observed the Markov Decision Processes. In this study, we delved into the utilization of MDPs within the context of a patient-centered and remote healthcare system. The significance of MDPs in this modern healthcare approach is increasingly recognized. MDPs are mathematical frameworks that calculate the likelihood of transitioning between various states. This methodology is particularly innovative in the management of Positive Airway Pressure (PAP) and oxygen titration, where it can make decisions taking into account the evolving respiratory health of patients, thereby facilitating informed and timely treatment decisions. Using different system evaluation methods can help identify system defects and correct them in further research (15).

The integration of MDPs into these algorithms allows for the consideration of the fluid nature of respiratory ailments. By doing so, treatment parameters can be adjusted based on the patient’s current health status and their medical history, ensuring a more tailored approach to care. The adaptability of these algorithms, underpinned by MDPs, marks a significant breakthrough in respiratory healthcare management. It enables healthcare providers to offer more accurate care remotely that not only brings the decision but is able to explain it. This approach aligns with the evolving landscape of healthcare, where personalized treatment and remote patient management are becoming increasingly important. The use of MDPs in this regard not only enhances patient outcomes but also streamlines the healthcare process, making it more efficient and responsive to patient needs.

Limitation. However, applying MDP necessitates gathering not only primary data related to treatment but also extensive meta-data or detailed data that are typically not collected during treatment. For example, detailed records of a patient’s restless sleep progression are often not documented. Additionally, the automatic construction of a Markov transition graph implies repeatedly taking all possible actions for each state, known as environment exploration. Of course, in medical scenarios, such an approach cannot be applied to patients. Instead, the transition matrix is constructed using existing treatment records, deviating from the idea of complete environmental exploration. Even with such an approach there is a risk of getting an imprecise model. E.g. in the study (16) it is mentioned that the estimates of rewards and transition dynamics used to parameterize the MDPs are often imprecise and lead the DM to make decisions that do not perform well with respect to the true system. The imprecision in the estimates arises due to these values being typically obtained from observational data or from multiple external sources (16). When the policy found via an optimization process using the estimates is evaluated under the true parameters, the performance can be much worse than anticipated (17). Another approach for building or testing policy is using simulations (18) that are possible in certain scenarios.

Markov Decision Process-based telemedical algorithms for patient treatment that begins with creating an initial graph using expert medical knowledge. This method addresses the challenges of limited data collection and incomplete environmental exploration. The crucial next step is refining this graph (

Figure 1) by testing it against historical patient treatment records to develop a transition matrix, a complex yet essential phase for building a functional Markov Decision Process. This approach, while intricate in implementation, is vital for overcoming inherent limitations similar to those faced by neural networks in predicting oxygen and pCO

2 fluctuations. It requires extensive, accurate data to create effective algorithms, a challenging but critical aspect of ensuring patient data quality and completeness. The optimism for this methodology stems from the demonstrated successes of machine learning in healthcare, particularly in enhancing patient outcomes in smaller, simulation-based studies. The future of this development lies in analyzing a larger pool of patient records, which will help in establishing statistical probabilities of state changes for more accurate predictions and individualized patient modeling, marking a significant step towards personalized healthcare through technology.

Despite the acknowledged challenges, Markov Process-based algorithms have potential to be additionally trained to specific patients’ respiratory conditions, using additional hidden layers. This may potentially improve patient outcomes and enhance the quality of care in the field of respiratory medicine.

In conclusion, the development of a framework for Markov Decision Processes of PAP and oxygen titration algorithms holds promise for providing algorithms for deviation in CO2 and SpO2 markers. While challenges remain, including the need for high-quality data, the potential benefits in terms of patient management and care optimization are substantial, and this approach represents an exciting frontier in the realm of telemedicine and respiratory healthcare.

Funding

Research was funded by the European Regional Development Fund project ”Machine learning-based clinical decision support system for the non-invasive ventilation devices in the treatment of COVID-19 patients” (Nr.1.1.1.1/21/A/082).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The above authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or the conclusions, implications or opinions stated.

Financial Disclosure

No financial disclosures to report by the above authors of the study.

Author Accountability Statement

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

References

- Kushida CA, Chediak A, Berry RB, Brown LK, Gozal D, Iber C, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Rowley JA, Positive Airway Pressure Titration Task Force, American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guidelines for the manual titration of positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(2):157-171. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Lee M, Hwangbo Y, Yang KI. Automatic Derivation of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Settings: Comparison with In-Laboratory Titration. J Clin Neurol. 2020;16(2):314-320. [CrossRef]

- Milner QJ, Mathews GR. An assessment of the accuracy of pulse oximeters. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(4):396-401. [CrossRef]

- Koczulla AR, Schneeberger T, Jarosch I, Kenn K, Gloeckl R. Long-Term Oxygen Therapy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(51-52):871-877. [CrossRef]

- Owens RL, Malhotra A. Sleep-disordered breathing and COPD: the overlap syndrome. Respir Care. 2010;55(10):1333-1346.

- Moloney ED, Kiely JL, McNicholas WT. Controlled oxygen therapy and carbon dioxide retention during exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2001;357(9255):526-528. [CrossRef]

- Puterman ML. Markov Decision Processes: Discrete Stochastic Dynamic Programming. John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

- Gao W, Jin Y, Wang Y, et al. Is automatic CPAP titration as effective as manual CPAP titration in OSAHS patients? A meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(2):329-340. [CrossRef]

- Gharib A. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on the respiratory system: a comprehensive review. Egypt J Bronchol. 2023;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Nowalk NC, Neborak JM, Mokhlesi B. Is bilevel PAP more effective than CPAP in treating hypercapnic obese patients with COPD and severe OSA? J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(1):5-7. [CrossRef]

- Ruan B, Nagappa M, Rashid-Kolvear M, et al. The effectiveness of supplemental oxygen and high-flow nasal cannula therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea in different clinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2023;88:111144. [CrossRef]

- Foresi A, Vitale T, Prestigiacomo R, Ranieri P, Bosi M. Accuracy of positive airway pressure titration through telemonitoring of auto-adjusting positive airway pressure device connected to a pulse oximetry in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Respir J. 2023;17(8):740-747. [CrossRef]

- NHS NIV Titration guidelines. 2023.

- Pépin JL, Bailly S, Rinder P, et al. CPAP Therapy Termination Rates by OSA Phenotype: A French Nationwide Database Analysis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):936. [CrossRef]

- Aalaei S, Amini M, Mazaheri Habibi MR, Shahraki H, Eslami S. A telemonitoring system to support CPAP therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a participatory approach in analysis, design, and evaluation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022;22(1):168. [CrossRef]

- Steimle LN, Kaufman DL, Denton BT. Multi-model Markov decision processes. IISE Trans. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Mannor S, Simester D, Sun P, Tsitsiklis JN. Bias and Variance Approximation in Value Function Estimates. Manage Sci. 2007;53(2):308-322. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20110697. [CrossRef]

- Kaneriya S, Chudasama M, Tanwar S, Tyagi S, Kumar N, Rodrigues JJP. Markov Decision-Based Recommender System for Sleep Apnea Patients. In: ICC 2019 - 2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); 2019. pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).